What happened

On 29 July 2013, about 64 NM (119 km) from Sydney the captain of Bombardier DHC-8-315 (Dash 8) aircraft, registered VH‑SBG and operated by QantasLink on a scheduled flight from Sydney to Wagga Wagga, New South Wales noticed a blank area in the centre of the flight management system (FMS) screen. About 10 minutes later the screen went completely blank and thick, light-grey smoke was observed coming from the unit.

The flight crew commenced the quick reference handbook Fuselage Fire or Smoke checklist, donning oxygen masks and smoke goggles. The crew found communication difficult while wearing their masks and, as a result, removed the masks for the remainder of the flight. The aircraft was diverted to Canberra, Australian Capital Territory. The flight crew were taken to hospital for observation and later released without needing treatment. No injuries were reported by the cabin crew or passengers. The aircraft sustained no other damage.

What the ATSB found

Examination of the FMS unit found that two capacitors failed, resulting in the smoke and failure of the unit. The unit was manufactured in 1997 and, in 1998, the FMS manufacturer introduced a modification to replace those capacitors in all subsequently manufactured units. However, there was no recall or retrofit program for unmodified FMS units already in service.

The ATSB also found that, at the time of the occurrence, the approved QantasLink training did not provide sufficient familiarity to first officers in the use of oxygen masks and smoke goggles. The more-experienced captain’s familiarity with the equipment was enhanced by completion of additional mask and goggles training sessions.

What's been done as a result

In October 2013, as a result of this occurrence, the FMS manufacturer issued a service bulletin for the optional incorporation of different capacitors to unmodified in-service FMS units.

QantasLink undertook a number of safety actions in response to this occurrence. This included installing modified FMS units to all aircraft in its Dash 8 fleet. QantasLink has also implemented a number of improvements to crew training, including improved oxygen mask and smoke goggle training and identifying alternate stowage for the flight deck fire extinguisher.

Safety message

This occurrence highlights the importance of flight crew familiarising themselves with the operation of the onboard emergency equipment. It also reminds crews that inhalation of fumes can have an adverse effect on an individual’s ability to function. Flight crew need to fully consider the implications of removing their emergency breathing equipment when in an environment where smoke and fumes are, or have been, present.

At about 1130 Eastern Standard Time[1] on 29 July 2013, the crew of Bombardier DHC‑8‑315 (Dash 8) aircraft, registered VH-SBG and operated by QantasLink, departed Sydney on a scheduled flight to Wagga Wagga, New South Wales. On board were two flight crew, two cabin crew and 49 passengers. The captain was the pilot flying,[2] and the first officer (FO) was the pilot monitoring.

About 64 NM (119 km) from Sydney, the captain noticed a 30 mm diameter ‘blank’ area in the centre of the flight management system (FMS) screen. The crew were still within radio contact range with QantasLink ‘maintenance watch’ so technical advice was sought. While the captain was talking to maintenance watch, the blank area disappeared and normal FMS function resumed. On receiving that information, maintenance watch personnel advised the crew that it was safe for the flight to continue to Wagga Wagga.

About 10 minutes later, the crew observed the FMS screen go completely blank, with thick, light‑grey smoke coming from the unit. At that time, the aircraft was out of radio range with maintenance watch so further advice could not be obtained. The captain reported that when the FMS screen went blank, it emitted a solid stream of light‑grey smoke for about 5 minutes. The smoke reduced to puffs of about 30-second intervals, before finally stopping about 3 minutes before landing.

There were no warnings or alerts while the solid stream of smoke was visible. The captain reported that immediately preceding the loss of the FMS screen, the presentation of navigation information was degraded.

At the first sign of smoke, the FO removed the Quick Reference Handbook from its stowage and commenced reading out the checklist action items for the non‑normal/emergency procedure Fuselage Fire or Smoke (appendix A). This resulted in the crew donning their oxygen masks and smoke goggles. The FO also removed the portable fire extinguisher from its stowage at the rear of the centre console and passed it to the captain.

The captain could not see anywhere in the FMS unit into which to discharge the extinguishing agent, so the fire extinguisher was placed on the floor adjacent to the captain’s seat.

Both flight crew reported communication was difficult while using the oxygen masks. This was due to an initial incorrect intercom setting. It was further exacerbated by the need to switch the mask microphone OFF between talking. The FO also reported that the communication difficulties resulted in an increased level of anxiety.

The captain asked the FO to contact Melbourne Centre air traffic control (ATC) to report the situation. The FO, believing the captain wanted to descend from their current cruise altitude of flight level (FL) 200[3], declared a PAN[4] and requested a descent. The flight crew reported that ATC did not initially understand the call, so the FO repeated the broadcast a number of times until ATC acknowledged the PAN. Noting the aircraft was maintaining the cruise level, the FO disconnected the autopilot and initiated a descent.

The captain did not recall discussing the need to descend and did not intend doing so at that time. As a result, when the FO initiated the descent, the captain re-engaged the autopilot, pulled back on the control column and declared having control of the aircraft. Both crew reported the FO disconnected the autopilot a second time in similar circumstances, although data from the flight recorder did not show this. The captain again re-engaged the autopilot and repeated ‘my controls’ so the FO would know the captain had taken control of the aircraft. Due to the ongoing communication issues, the captain instructed the FO to remove their mask to improve communication between the crew. Both crew removed their masks and goggles to discuss the situation.

As the FMS was no longer functioning, the FO asked ATC for the nearest airport and was told Canberra was 30 NM (56 km) away. The crew advised ATC they would divert to Canberra and requested and received radar vectors for approach to Canberra Airport, Australian Capital Territory.

The captain briefed the cabin crew and made a public address to alert the passengers of the intention to divert to Canberra with a landing in about 10 minutes. At that time, the smoke in the flight deck had reduced to about 50 per cent of its original rate. As neither crew felt they were experiencing ill effects from the smoke, they did not refit their masks or goggles.

During the descent, the flight crew returned to the Quick Reference Handbook checklist items but misread a note that resulted in them ceasing the Fuselage Fire or Smoke checklist to allow commencement of the normal landing checks. The smoke had almost cleared from the flight deck by the time the aircraft commenced the approach. After touchdown, the aircraft was turned onto taxiway Golf where it was stopped and a precautionary disembarkation of the passengers and crew carried out.

The flight crew had flown without wearing their masks and smoke goggles for about 10‑15 minutes. As a result, they were taken by ambulance to a local hospital for monitoring, before being released some hours later.

No passengers or cabin crew reported injuries or ill effects from the smoke. There was no other damage to the aircraft.

__________

- Eastern Standard Time (EST) was Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) + 10 hours.

- Pilot Flying (PF) and Pilot Monitoring (PM) are procedurally assigned roles with specifically assigned duties at specific stages of a flight. The PF does most of the flying, except in defined circumstances; such as planning for descent, approach and landing. The PM carries out support duties and monitors the PF’s actions and aircraft flight path.

- At altitudes above 10,000 ft in Australia, an aircraft’s height above mean sea level is referred to as a flight level (FL). FL 200 equates to 20,000 ft.

- An internationally recognised radio call announcing an urgency condition which concerns the safety of an aircraft or its occupants but where the flight crew does not require immediate assistance.

Personnel information

Captain

The captain commenced flying in 2002, held an Air Transport Pilot (Aeroplane) Licence and had a current Class 1 Medical Certificate. Their total aeronautical experience was about 3,525 hours, with about 2,000 hours on the Dash 8 aircraft type.

During the previous 7 days, the captain was on duty for 4 days, on stand-by (without call-out) for 1 day and then had 2 days off duty. The previous duty concluded at about 2255 on 25 July 2013. The captain reported being on duty for 3 hours at the time of the occurrence, having been awake for 6 hours. The captain did not report any fatigue‑related concerns or any illness leading up to the occurrence.

First officer

The first officer (FO) held a Commercial Pilot (Aeroplane) Licence and had a current Class 1 Medical Certificate. They had a total aeronautical experience of about 2,531 flying hours.

During the previous 7 days, the FO had 1 day on duty, 2 days off duty, and then 4 days on duty. The previous duty concluded at 1531 on 28 July 2013. The FO reported being awake for 4 hours and on duty for 2 hours at the time of the occurrence and did not report any fatigue‑related concerns or any illness at that time.

Emergency procedures training

Oxygen masks and goggles

As part of endorsement training, crew were required to conduct a rapid depressurisation simulator session. This session required the rapid donning and ongoing use of oxygen masks and:

- included making a single radio transmission to air traffic control

- included crew-to-crew communication

- did not involve wearing the smoke goggles (as they were not required by the training scenario)

- included the initiation of an emergency descent with the engines at the flight idle power setting

- included the initiation of an emergency descent at the maximum operating airspeed.

Further rapid depressurisation sessions were conducted as part of command upgrade or other recurrent training. QantasLink also provided annual emergency procedures training. This training was theory‑based and covered the use of the emergency equipment including the oxygen masks, but not wearing, or communicating while wearing the mask. The emergency procedures training did not incorporate wearing the smoke goggles.

Training records indicated that since commencing employment with QantasLink in 2008, the captain had undertaken three rapid depressurisation simulator sessions. The most recent session was in 2011 on the DHC-8-402 aircraft that was fitted with a different type of oxygen mask. The captain had also undergone five emergency procedures training sessions. The captain reported not having previously worn the oxygen mask or smoke goggles during a flight.

The FO reported completing a rapid depressurisation simulator session about 18 months prior to the occurrence. That was the only occasion that the FO had worn the oxygen mask prior to the occurrence flight. Training records indicated that the FO completed three emergency procedures training sessions.

The FO advised that, during the initial simulator session, only one radio transmission was made while wearing the mask and that after the aircraft had descended to the safe altitude, the oxygen mask was able to be removed. The FO had not worn the smoke goggles prior to the occurrence flight.

Portable fire extinguisher

Neither crew member had used the portable fire extinguisher previously. As part of QantasLink’s investigation into the occurrence, a simulation was conducted where flight crew had to remove and then replace the portable fire extinguisher in its stowage. That simulation revealed that while seated, neither crew could refit the fire extinguisher in its stowage and secure it correctly. The aircraft manufacturer’s Fuselage Fire or Smoke checklist, which had been adopted by QantasLink, included a step to extinguish any fire with the portable extinguisher. No specific instruction was provided in the checklist regarding the stowage of an empty or unused extinguisher.

Aircraft information

Flight management system

General

The flight management system (FMS) was a fully integrated navigation management system designed to provide the crew with computer-based flight planning, fuel management and centralised control for the aircraft's navigation sensors. The aircraft incorporated a single FMS unit located on the left side of the centre console, adjacent to the captain’s seat (Figure 1).

Examination of the failed flight management system unit

The FMS unit was sent to the manufacturer for examination. That examination found that there had been a dielectric breakdown[5] of a capacitor, which then acted as a low resistance load. This resulted in self-heating that led to the failure of that capacitor, of an adjacent capacitor and of a diode. Other signs of excessive heating were visible on a number of circuit boards, including the display circuit board and connector ribbons within the unit.

In November 1998, because of previous unit failures, the manufacturer released an engineering change order to replace the capacitors affected in this occurrence with components of a higher rating. That modification applied to newly-built units only, and was not retrospectively applied to existing units. As a result, a number of unmodified units remained in service globally.

The circuit board containing the failed capacitors and diode was in original condition and had not been modified. The capacitors were of a different rating, which did not meet the manufacturer’s post-1998 specifications.

Figure 1: DHC-8-315 instrument panel showing the location of the FMS on the captain’s side of the centre console (detailed view of the FMS at inset)

Source: QantasLink

FMS service history

The failed FMS unit, part number 10172-41-111, serial number 1590, was manufactured in 1997 and was acquired from the manufacturer as an overhauled unit by QantasLink in April 2010.

A review of the unit’s service history revealed that it entered service in November 2010 and was removed 438 hours later due to the screen going blank. In May 2011, the unit was returned to service and removed 2,808 hours later due to a backlight problem on the display panel. The unit was returned to service in March 2013 and was removed 671 hours later due to this occurrence. Following this occurrence, the unit was returned to service in August 2013 but was again removed 141 hours later due to the display being permanently set to full brightness.

Flight crew emergency oxygen system

The aircraft flight deck contained a fixed emergency oxygen system comprising of captain and FO half-face (oronasal) masks. The masks were suspended on quick-release hangers from the ceiling panel above and behind each crew seat. Each mask contained a microphone and a regulator that supplied normal or 100 per cent oxygen, either on demand or as continuous flow.

Communication using the mask microphone required the user to select the intercom switch on the communications panel at the rear of the centre console from BOOM (headset microphone) to MASK (mask microphone). The press-to-talk switches on the control columns were then required to be toggled ON when the individuals were speaking and OFF when finished. This was to prevent distraction for the other crew member from breathing noises associated with a live microphone.

During the first flight of the day, flight crew were required to check the serviceability of the emergency oxygen equipment. This included:

- a visual inspection of the condition of the oxygen mask

- checking the mask is connected to the oxygen supply

- testing for continuous flow of oxygen

- confirmation that the ‘100%/Dilute’ selector is in the 100 per cent position

- checking the operation of the oxygen mask microphone.

The fitment of the smoke goggles was not routinely carried out as part of that check.

Operational factors

QantasLink DHC-8 Fuselage Fire or Smoke checklist

The aircraft manufacturer’s Quick Reference Handbook (QRH) was used by QantasLink. The QRH contains information derived from the Approved Airplane Flight Manual. It is used by flight crew to confirm that respective procedures have been performed correctly.

The QRH contains checklists for Normal and Non-normal/Emergency situations. The Non‑normal/Emergency checklists contain only those items and procedures that differ from those for normal aircraft operation.

The Fuselage Fire or Smoke checklist was divided into four sections (appendix A):

- ‘boxed’ action items (the recall/memory action items) and landing considerations

- Known Source of Fire or Smoke action items

- Unknown Source of Fire or Smoke action items

- Source of Fire or Smoke cannot be identified action items.

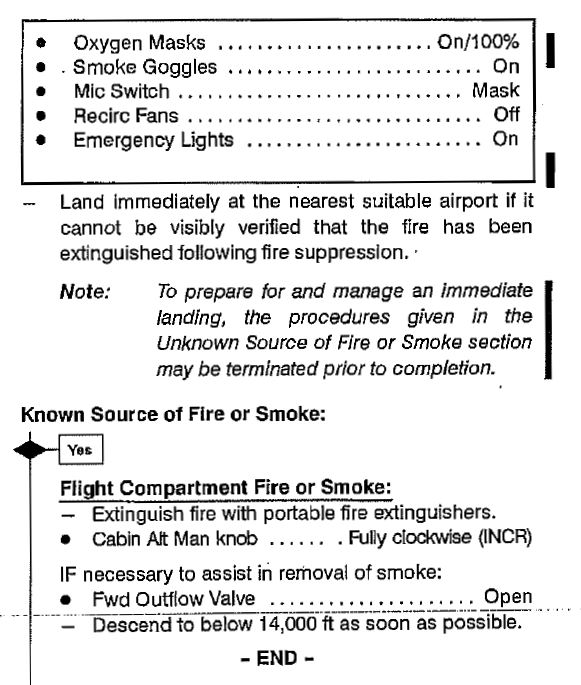

The boxed action items that were applicable on the occurrence flight are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Dash 8 Quick Reference Handbook extract showing the procedural action items in the case of a fire or smoke in the cockpit from a known source (from the FMS in this case)

Source: QantasLink

The Known Source of Fire or Smoke section of the checklist did not contain action items for removal of electrical power from affected systems, such as the FMS. The aircraft manufacturer advised the ATSB that the checklist relied on the flight crew isolating, as required, affected equipment from the aircraft’s electrical system through the operation of any integrated power switch. Reconfiguration of the aircraft’s electrical system in response to a fire or smoke situation of unknown origin was contained in other sections of the checklist (appendix A).

Flight crew actions

Quick reference handbook

On observing the smoke, the FO removed the QRH from its location at the rear of the centre console, located the Fuselage Fire or Smoke checklist, and commenced reading out the recall/memory action items. After donning their masks and goggles, the recirculation fans were selected to OFF. The FO went to select the emergency lights ON but was told to leave them off by the captain, who did not want to alarm the passengers or be distracted with cabin crew enquiries.

While actioning the checklist, the crew were interrupted multiple times with calls from air traffic control and QantasLink. Each time the crew were interrupted, they recommenced the checklist at the start to ensure all actions were conducted.

The crew briefly returned to the Fuselage Fire or Smoke checklist at about 8,000 ft. The FO read out the note that followed the recall actions. This allowed for the discontinuation of the procedures in response to an unknown source of smoke or fire prior to their completion. This was to facilitate preparations for an immediate landing. However, this was misheard by the captain as being applicable to their situation of a known source of fire or smoke – the FMS.

As a result, the checklist was terminated at that point. This meant that the forward outflow valve was never opened, which would have, if activated, assisted in the removal of the smoke from the flight deck.[6]

At the time the Fuselage Fire or Smoke checklist was inadvertently stopped, the normal approach and landing checklist became the priority, so the Fuselage Fire or Smoke checklist was not returned to, nor completed.

Oxygen masks

Both crew reported communication difficulty while wearing their oxygen masks. This difficulty related to both inter‑crew communication and communication between the FO and air traffic control. As a result of this difficulty, and the FO disengaging the autopilot, the captain directed the removal of oxygen masks. The oxygen masks were not worn for the remainder of the flight.

Neither crew reported suffering ill effects from the smoke and were subsequently medically cleared after landing.

Tests and research

Fume and smoke hazards

There has been extensive research into the effects of fumes and smoke in aircraft. The United States Federal Aviation Administration pilot safety brochure Smoke toxicity[7] highlights that smoke inhalation should be recognised as a very real danger. It also states that ‘smoke gas levels do not need to be lethal to seriously impair a pilot’s performance’.

ATSB research report AR-2013-213 Analysis of fumes and smoke events in Australian aviation from 2008 to 2012: A joint initiative of Australian aviation safety agencies,[8] found that over 1,000 fumes/smoke events were reported to the ATSB and the Civil Aviation Safety Authority in the period 2008–2012. From the data gathered, it was apparent that the most common source of fumes/smoke was the malfunction or failure of electrical systems and auxiliary power units.

The ATSB research report also identified a significant increase in reported fumes/smoke events from mid-2011, which was independent of the growth in flying activity. The report highlights that fumes relating to electrical failures may have the potential to pose a health risk through eye/skin irritation, difficulty in breathing, incapacitation or illness. This was especially the case if the fumes were associated with particulates (smoke) or fire. However, while the potential for a serious outcome is more likely from an occurrence involving smoke, the research also found that ‘very few led to a serious consequential event (such as a forced landing) or outcome such as fire or crew incapacitation’.

Other occurrences

Australia

QantasLink advised there had been a total of five FMS fire/smoke events within their fleet of Dash 8 aircraft during the period 2004–2013. One other Dash 8 operator in Australia had experienced an FMS smoke event, which occurred in 2011. The remaining Australian Dash 8 operators reported they had not experienced any FMS fire/smoke events within their fleets.

A review of the ATSB occurrence database confirmed that six Dash 8 FMS fire/smoke events were reported between 2007 and 2013 across all Australian Dash 8 operators. In one such event on 24 March 2007, while conducting a scheduled flight from Cairns to Horn Island, Queensland, the flight crew of Dash 8 aircraft, registered VH-SBV, reported the aircraft’s FMS unit ceased operating. About 60 seconds later, smoke was observed emanating from the FMS unit. As a precaution, the flight crew donned their oxygen masks and smoke goggles. After completing the action items in the Fuselage Fire or Smoke checklist, the captain ‘pulled’ (opened) the circuit breaker for the FMS to isolate electrical power. That action, while not in accordance with procedures or the checklist, resulted in the smoke ceasing. The opening of the forward outflow valve, in accordance with the checklist, resulted in the rapid removal of smoke from the flight deck.

Worldwide

The ATSB also reviewed a number of international safety databases. While that review found numerous reported smoke/fire events for the Dash 8 aircraft, it did not identify any additional FMS‑related occurrences.

__________

- Dielectric breakdown refers to a rapid reduction in the resistance of an electrical insulator when the voltage applied across it exceeds the breakdown voltage.

- This step in the QRH calls for crews to open the valve ‘if necessary to assist in removal of smoke’.

- Available at www.faa.gov.

- Available at www.atsb.gov.au.

Introduction

The failure of the flight management system (FMS) unit and subsequent smoke in the cockpit led to the flight crew diverting the aircraft to Canberra Airport, Australian Capital Territory. This analysis will examine the failure mode of the FMS unit, the actions of the flight crew, operational issues and organisational factors that had the potential to affect the flight.

Flight management system failure

The failure of the FMS unit was due to the dielectric breakdown and overheating of one of the unit’s capacitors. The FMS manufacturer had reviewed the suitability of the capacitors in the early model FMS units and implemented a design modification to upgrade the capacitors in 1998. This was done through an engineering change order, which was implemented about 12 months after the release to service of the FMS unit installed in VH-SBG.

Despite the availability of this modification, the FMS manufacturer did not have a retrospective fitment program for in‑service units. Such a program could be expected to reduce the likelihood of capacitors overheating and therefore in-flight FMS failures and subsequent fire/smoke occurrences. The manufacturer was unable to provide details of the number of unmodified units currently in service, which made evaluation of the risk of further in‑service failures as a result of this failure mode difficult to determine. However, in Australia, QantasLink commenced an upgrade of their FMS units in February 2014 to meet the new design specification under service bulletin SB10172.XX.()‑34‑3578 Installation of Mod 22 in the UNS-1C+ FMS. This upgrade was completed in June 2014.

Operational factors

Flight crew actions

As would be expected in any emergency situation, the appearance of smoke from the FMS created a level of stress for the flight crew. Their immediate response was to review the Quick Reference Handbook and action the Fuselage Fire or Smoke checklist. The first step was to put oxygen masks on, followed by fitting the smoke goggles before continuing the checklist.

During this time, the crew were interrupted numerous times due to the need to respond to air traffic control (ATC) and calls from QantasLink via radio as the first officer (FO) was reading out the checklist. After each interruption, the checklist was recommenced from the start. However, reports from the crew indicated that communication both between them and with ATC while wearing the oxygen masks was difficult. Consequently, the FO had to repeat the PAN call to ATC multiple times before being understood. This added to the crew’s stress and workload in trying to resolve this difficulty.

Research has shown that, under stressful conditions, the performance of tasks can be affected so that the outcomes are not as planned or in conformance with a procedure (Wickens and Hollands, 2000). The effects of stress on human performance have been characterised as:

- Attentional narrowing, where an individual’s attention can concentrate on a single aspect of a task at hand to the detriment of other information cues or task requirements.

- Perseveration[9], where an individual perseveres with a given action or plan they have used in the past, even if it is failing to provide a successful solution.

- Confirmation bias, where a decision maker, once locked into a hypothesis on the reason behind an event, will be less likely to consider information cues that might support an alternative hypotheses.

The combined influence of those characteristics can contribute to a pattern of convergent thinking or ‘cognitive tunnelling’. This will initially narrow the set of cues processed by the individual to those they perceive as being the most important. As the cues have been viewed to support one hypothesis only, the individual will continue to consider that hypothesis only, and process a restricted range of cues consistent with that set.

The FO’s action to reduce altitude appears based on recognising this requirement from the training in simulated rapid depressurisation procedures. The captain did not recall discussing descending the aircraft with the FO at that time and was not aware that the FO had advised ATC they intended doing so. Consequently, the captain was surprised by the FO’s actions and immediately re-engaged the autopilot.

After the FO attempted to descend the aircraft without a direction to do so from the captain (who was the pilot flying) and, recognising that the FO was anxious, the captain ordered the removal of the oxygen masks. As the smoke goggles and oxygen masks were ‘tangled’ together, both crew members’ masks and goggles remained off for the remainder of the flight.

The captain reported that once the oxygen masks were removed, and better communications established as a result, the FO contacted ATC and determined that Canberra was the closest suitable airport. The crew requested radar vectors for Canberra from ATC as the FMS was no longer working. The captain stated that descent from FL 200 normally required about 60 NM (111 km). In this instance, the aircraft’s proximity to Canberra meant that the crew had to prepare for the descent and landing over a remaining distance of 30 NM (56 km). This resulted in a similar number of tasks being carried out in a reduced period of time.

Workload has been defined as ‘reflecting the interaction between a specific individual and the demands imposed by a particular task. Workload represents the cost incurred by the human operator in achieving a particular level of performance’ (Orlady and Orlady, 1999). A discussion of the effect of workload on the completion of a task requires an understanding of an individual’s strategies for managing tasks.

An individual has a finite set of mental resources they can assign to a set of tasks (for example, performing a take-off). These resources can change given the individual’s experience and training and the level of stress and fatigue being experienced at the time. An individual will seek to perform at an optimum workload by balancing the demands of their tasks. When workload is low, the individual will seek to take on tasks. When workload becomes excessive the individual must, as a result of their finite mental resources, shed tasks.

An individual can shed tasks in an efficient manner by eliminating performance on low priority tasks. Alternately, they can shed tasks in an inefficient fashion by abandoning tasks that should be performed. Tasks make demands on an individual’s resources through the mental and physical requirements of the task, temporal demands and the wish to achieve performance goals (Hart and Staveland, 1988 and Lee and Liu, 2003).

The inherent stress of the event, together with the associated high workload led to the crew making errors in both aircraft management and checklist completion. This included not completing the ‘transition drill’ when passing 10,000 ft on descent, which includes checking, and changing as required, the fuel system, exterior lights, pressurisation and ice protection. These drills were conducted at 8,000 ft prior to conducting the approach checklist.

As part of the initial conduct of the checklist, the FO retrieved the fire extinguisher and handed it to the captain. However, as the FMS was still an intact, sealed unit, there was no way for the extinguisher to be used on the FMS. The captain’s decision to place the unused fire extinguisher on the floor adjacent to the seat may have been influenced by the impracticality of re-securing the fire extinguisher in the normal stowage location. Consequently, the fire extinguisher presented a potential projectile hazard within the flight deck.

The captain stated that passing about FL 120 the FO was requested to continue with the Fuselage Fire or Smoke checklist. The captain reported a number of interruptions at about this time to the extent that the FO was unable to recommence reading out the checklist actions until passing about 8,000 ft. These interruptions included the previously mentioned numerous ATC calls and from QantasLink ground personnel, enquiries from cabin crew and the need to make a public address announcement to the passengers.

When the Fuselage Fire or Smoke checklist was recommenced just prior to 8,000 ft, the captain misheard the cessation note as read out by the FO. This note was designed to highlight the need to prepare for and manage an immediate landing if the source of fire or smoke could not be identified and that to do so, the checklist could be terminated. It is likely that when this note was read out, the proximity to Canberra and the need to conduct the approach and landing checklist reinforced the captain’s decision to terminate the checklist at this point, despite it applying to an unknown source of fire.

In both the crew’s initial action to carry out the Fuselage Fire or Smoke checklist, and its review at 8,000 ft, circumstances prevented the completion of the Known Source of Fire or Smoke section. In both cases, the action to open the ‘forward outflow valve’ was missed. However, the associated note for this action specified its completion ‘if necessary to assist in removal of smoke’. Given the crew reported the smoke had dissipated by the time the approach was commenced into Canberra, even if this step was reached, it is unlikely it would have needed to be actioned.

Emergency equipment training

All QantasLink flight crew underwent a rapid depressurisation scenario simulator session as part of their Dash 8 endorsement training. Additional rapid depressurisation training was undertaken as part of command upgrade for captains. The crew were required to undertake emergency procedures training annually but this was primarily theory based.

QantasLink provided limited training in the use of smoke goggles and no training on using the goggles in combination with the oxygen mask. Both crew confirmed that the only training provided in the use of oxygen masks was during a rapid depressurisation scenario, which was reported not frequently practiced.

Resolution of emergency situations relies on effective decision making by crews given the information available. Emergency procedure training provides the opportunity for crews to familiarise themselves with those procedures for use in times of high stress and workload. In this instance, the lack of prior exposure to wearing smoke goggles in a training environment increased the risk of reduced flight crew performance in response to the occurrence.

Both crew reported being confident in the use of the oxygen mask. However, their infrequent practice using the mask microphone to communicate increased the risk of communication breakdown as experienced during this occurrence.

The communication difficulties experienced by the crew in this occurrence contributed to their decision to remove their oxygen masks. Despite addressing the problem of communication, it also resulted in their re-exposure to potentially harmful smoke/fumes. While the crew reported no adverse effects from this exposure, it did increase the risk of crew impairment/incapacitation.

__________

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the failure of the flight management system unit and subsequent smoke on the flight deck occurrence involving Bombardier DHC-8-315 aircraft, registered VH-SBG, near Canberra Airport, Australian Capital Territory on 29 July 2013. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

Safety issues, or system problems, are highlighted in bold to emphasise their importance. A safety issue is an event or condition that increases safety risk and (a) can reasonably be regarded as having the potential to adversely affect the safety of future operations, and (b) is a characteristic of an organisation or a system, rather than a characteristic of a specific individual, or characteristic of an operating environment at a specific point in time.

Contributing factors

- The flight management system unit failure and observed smoke were the result of a capacitor, which did not meet current design specifications, overheating.

- Despite a design upgrade in 1998 for new flight management system units, unmodified units remained in service that had the original capacitors.

- At the time of the occurrence, the approved QantasLink training did not provide first officers with sufficient familiarity on the use of the oxygen mask and smoke goggles. This likely contributed to the crew's communication difficulties, including with air traffic control. [Safety issue]

Other factors that increased risk

- Despite removing their oxygen masks to improve communication, by doing so the crew increased the risk of impairment or incapacitation as there was still smoke in the cockpit.

- The stress associated with the smoke in the cockpit resulted in a high workload for the crew and adversely affected their performance, leading to errors in aircraft management and checklist completion.

The safety issues identified during this investigation are listed in the Findings and Safety issues and actions sections of this report. The ATSB expects that all safety issues identified by the investigation should be addressed by the relevant organisation(s). In addressing those issues, the ATSB prefers to encourage relevant organisation(s) to proactively initiate safety action, rather than to issue formal safety recommendations or safety advisory notices.

All of the directly involved parties were provided with a draft report and invited to provide submissions. As part of that process, each organisation was asked to communicate what safety actions, if any, they had carried out or were planning to carry out in relation to each safety issue relevant to their organisation.

The initial public version of these safety issues and actions are repeated separately on the ATSB website to facilitate monitoring by interested parties. Where relevant the safety issues and actions will be updated on the ATSB website as information comes to hand.

Emergency oxygen mask and smoke goggles training

At the time of the occurrence, the approved QantasLink training did not provide first officers with sufficient familiarity on the use of the oxygen mask and smoke goggles. This likely contributed to the crew's communication difficulties, including with air traffic control.

ATSB Safety Issue: AO-2013-120-SI-01

Additional safety action

Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence.

QantasLink

QantasLink has undertaken the following additional safety actions:

- Amended the Aircrew Emergency Procedures Manual to include post‑precautionary evacuation procedures and post‑incident debriefings to all flight and cabin crew. This includes in crew emergency procedures training.

- Completed a program in June 2014 to modify all QantasLink flight management system units to incorporate 22uF/25V capacitors in accordance with service bulletin SB10172.XX.()-34-3578 Installation of Mod 22 in the UNS‑1C+ FMS.

- Amended their emergency procedures training to include alternative stowage of fire extinguishers in the flight deck.

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included the:

- flight crew of VH-SBG

- QantasLink

- Bombardier Inc

- flight management system manufacturer

- United States National Transportation Safety Board

- United Kingdom Air Accidents Investigation Branch

- Transportation Safety Board of Canada.

References

Hart, SG & Staveland, LE 1988, ‘Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of empirical and theoretical research’, In PA Hancock & N Meshkati (Eds.), Human Mental Workload. North Holland Press, Amsterdam.

Lee, YH & Liu, BS 2003, ‘Inflight workload assessment: Comparison of subjective and physiological measurements’, Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, vol.74, pp. 1078‑1084.

Orlady, HW & Orlady, LM 1999, Human factors in multi-crew flight operations. Ashgate, Aldershot, p. 203.

Wickens, CD & Hollands, JG 2000, Engineering psychology and human performance. 3rd Edition. Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

Submissions

Under Part 4, Division 2 (Investigation Reports), Section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 (the Act), the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. Section 26 (1) (a) of the Act allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the crew of VH‑SBG, QantasLink, the Civil Aviation Safety Authority, Bombardier Inc, the flight management system manufacturer, United States National Transportation Safety Board and the Transportation Safety Board of Canada.

Submissions were received from the captain of VH-SBG, QantasLink and the Civil Aviation Safety Authority. The submissions were reviewed and where considered appropriate, the text of the draft report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2017

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |