Executive summary

What happened

On 7 December 2023, an Agusta A109E helicopter was conducting a marine pilot transfer operation. While landing on the ship Tai Keystone, the aircraft struck a handrail resulting in substantial damage to the tail rotor and minor damage to the vessel.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that the handrail had not been removed during the preparation of the helicopter landing site. It was also found that the ship’s crew was using an older version of a checklist which did not require their removal. This item was however included in the latest version of the International Chamber of Shipping Guide to Helicopter/Ship Operations checklist current at the time of the occurrence.

The ATSB also determined that the handrail would have been difficult for the helicopter pilot to detect as it had been painted in a colour which did not contrast with the colours used on the ship deck. This was not in accordance with the guidance for shipboard helicopter landing sites in the International Chamber of Shipping Guide to Helicopter/Ship Operations. Additionally, during the landing, the helicopter was not positioned correctly on the helicopter landing site. This resulted in the tail rotor being outside the obstacle free zone and striking the handrail.

It was also identified that the Civil Aviation Safety Authority Advisory Circular 139 Guidelines for heliports - design and operation did not include guidance material for the marking of objects, except for wind direction indicators, located on the helicopter landing site.

Finally, the Australian Maritime Safety Authority Marine Order 57 – Helicopter operations referenced an outdated version of the International Chamber of Shipping Guide to Helicopter/Ship Operations.

What has been done as a result

Taiwan Navigation Co. Ltd, have updated their helicopter/ship operation safety checklist to include the following checklist items:

- the deck party is aware that a landing is to be made

- the operating area is free of heavy spray or seas on deck

- the side rails and, where necessary, awnings, stanchions and other obstructions have been lowered or removed

- all personnel been warned to keep clear of rotors and exhausts

- the ship operator will now be notified of updates to the International Chamber of Shipping Guide to Helicopter/Ship Operations when new versions are published.

Jayrow Helicopters have amended their procedures to ensure that helicopter pilots are provided with visual representation of each individual vessel helicopter landing site prior to departure. They were also developing a new pilot checklist that included a requirement to ensure no obstacles existed in the helicopter landing area.

The Australian Maritime Safety Authority noted the reference to the outdated guide and will include this for correction in a planned review of Marine Order 57.

Safety message

It is the responsibility of the pilot in command to ensure that a landing area is safe. Where possible, helicopter pilots should attempt to gather as much information about the helicopter landing site (HLS) prior to departure and conduct an inspection of the intended landing area before commencing an approach to land. Photographs and obstacle maps of the HLS can be a valuable source of information to assist helicopter pilots with threat identification.

Objects that present a threat to a landing helicopter that are retractable, collapsible or removable should be painted in an appropriate colour to ensure they are visible if forgotten or missed. The use of reflective tape or lighting also increases the visibility of these objects.

Additionally, vessel operators should ensure their procedures and the landing area on the ship are aligned with the relevant guidance material.

The occurrence

On 6 December 2023 at 2015 local time, the merchant vessel Tai Keystone, departed Hay Point, Queensland for Tachibana, Japan. The vessel’s route passed through the Great Barrier Reef via the Hydrographers Passage and due to its size (over 70 m in length), the Tai Keystone required a marine pilot[1] to assist navigating this route.

The Tai Keystone departed Hay Point with the marine pilot on board and reached the start of the compulsory pilotage area for Hydrographers Passage at about 0100 on 7 December. The vessel completed the passage at about 0730 and the marine pilot was relieved of duty. As the marine pilot did not expect to depart the vessel for several hours they left the ship’s bridge to obtain rest in the sleeping quarters.

At about 0830, an Agusta A109E helicopter, registered VH-RUA, departed Mackay, Queensland with just the pilot onboard. The pilot planned to land on the Tai Keystone to retrieve the marine pilot and then proceed to another ship, to conduct a second marine pilot retrieval, before returning to Mackay Airport.

The helicopter was flown north‑east from Mackay and at about 1012 the helicopter pilot attempted to establish communication with the Tai Keystone for the first landing however, this was unsuccessful. Another attempt to establish communication was successful at about 1027, 15 minutes prior to landing.

Due to slope landing limitations, the helicopter pilot requested information on the extent to which the vessel was rolling[2] and the master[3] of the ship advised it was between 3–5°. As this was at the helicopter operator’s limit of 5° for daylight operations, the helicopter pilot requested the marine pilot join the ship’s master on the bridge to give instructions to help reduce the ship’s roll.

The marine pilot arranged for the vessel’s heading to be changed to 340°, which reduced the roll to approximately 2°. The helicopter pilot was informed that the emergency crew was on standby, and that the master had given permission for the helicopter to land.

The helicopter pilot completed their pre-landing checks and, while at 300 ft on approach to the ship, conducted a visual inspection of the shipboard helicopter landing site (HLS).[4] They advised that, while they had not landed on this ship previously, this height was close enough to do an effective reconnaissance of the HLS. The pilot noted red manhole covers, where they would normally land the nose wheel, as the only obstacles inside the landing area. Having assessed that these did not present a threat as the helicopter could land clear of the manholes, they continued the approach.

At about 1042, the helicopter landed on the ship and as the wheels touched the deck, the tail rotor struck an upright handrail that was not identified by the pilot during the approach. The helicopter pilot reported hearing a shredding noise and an increase in the engine pitch before completing the emergency shutdown procedure.

The helicopter sustained substantial damage and was secured to the deck of the Tai Keystone, which then returned to Hay Point to assist with removal of the helicopter from the vessel.

Context

Helicopter Pilot

The pilot of the helicopter held a commercial pilot licence (helicopter) with a multi‑engine helicopter class rating. Their total flight experience at the time of the incident was 4,880 hours with 300.8 hours on the Agusta A109E and they had recently completed both a proficiency check and line check to a satisfactory standard. The helicopter pilot also held a current class 1 medical certificate.

Helicopter

The helicopter was an Agusta A109E, which was manufactured in 2001 and issued serial number 11129. It was registered in Australia in 2010 as VH-RUA and began operations with the operator in 2017. The Agusta A109E is a multi-engine helicopter with 2 Pratt & Whitney PW206-C engines driving a 4-blade main rotor and a 2-blade tail rotor.

The ATSB was provided aircraft flight data from the onboard spider track recording device. The data provided an updated aircraft position at a maximum of 15 second intervals.

Vessel

The merchant vessel Tai Keystone was a bulk carrier with an overall length of 228.41 m, it was built in 2017 and provided the unique ship identifier number 9789843 by the International Marine Organisation (IMO). The vessel was operated by the Taiwan Navigation Co Ltd and registered under the Panama flag.

The vessel had several hatch-covers, one of which was used as a shipboard HLS when needed (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Exemplar vessel for reference

Image source: ATSB investigation MO-2016-003 annotated by the ATSB

Handrails

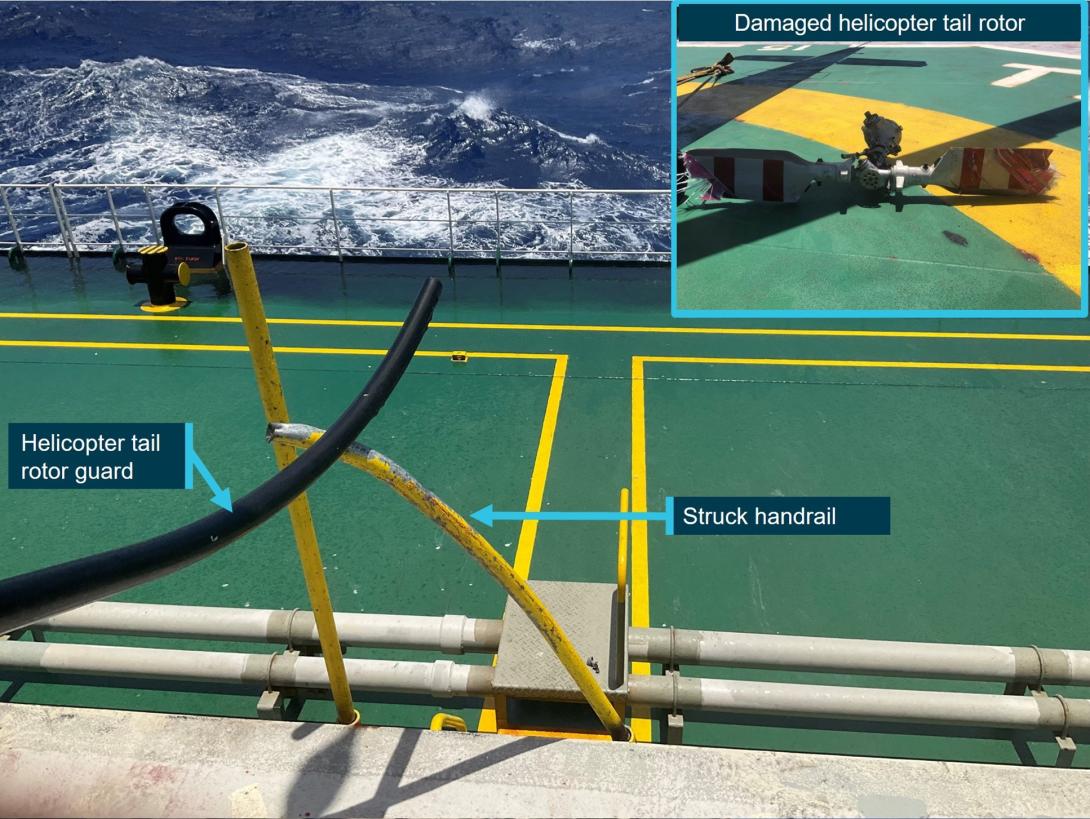

Handrails or stanchions[5] are used as an extension of the ladders installed to gain access to the shipboard HLS (Figure 2). The handrails are removable and usually stowed when the ship is underway. They are normally only installed once the helicopter has landed and removed prior to its departure. The handrails were painted yellow and were about 2.5 cm in diameter by 1 m tall. It was reported that these types of handrails were not considered to be a common feature on vessels.

The marine pilot on board the ship advised they instructed the vessel’s crew to remove the handrails before the helicopter arrived. This request occurred prior to the marine pilot going to the sleeping quarters and when they returned to the bridge, they did not confirm whether this action had been completed.

Figure 2: Starboard[6] handrails (removed at the time of the occurrence)

Image source: helicopter pilot in command

The helicopter pilot reported that, after exiting the helicopter, they observed the vessel’s starboard‑side handrails were removed. However, the port‑side handrails that were struck were still installed (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Handrail positions

Image source: helicopter pilot in command

The HLS was predominantly painted in green with a yellow circle and a white ‘H’. The vessel’s name was also painted in white in the HLS. There was a permanent yellow ladder (Figure 2) leading up to the HLS and yellow painted walkway lines leading to the ladder, on the deck of the ship (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Struck handrail and damaged tail rotor

Image source: helicopter pilot in command

Communication

Once the marine pilot joined the master on the bridge, they advised the helicopter pilot that:

- the wind was from 080° at 20 kt

- the ship was not pitching

- there was no sea spray

- emergency crews were on standby

- the helicopter had the master’s permission to land.

No information on obstacles was passed to the helicopter pilot.

Helicopter approach

The helicopter pilot advised that they commenced their approach from behind the Tai Keystone on the port[7] side of the vessel as it provided a clear view of the vessel from their position on the right side of the helicopter.

The pilot reported that once the helicopter was turned to align with the HLS, which occurred after they completed their reconnaissance, the instrument panel obscured the undershoot area of the HLS, so they could only see the landing area and not the entire hatch cover. They further advised that, due to the position of the manhole covers, they ensured that during the landing, the nose wheel was slightly back on the ‘H’ on the HLS (Figure 5). It was reported by both the helicopter and marine pilots that it was common for the helicopter tail rotor to hang over the edge of the hatch to avoid other obstacles, such as pipes and vents.

The helicopter pilot also advised that at 300 ft, a narrow yellow pole was almost impossible to detect. In addition, the ladder leading to the poles was painted yellow, there was yellow on the hatch, and yellow lines on the edge of the landing hatch (the yellow walkway) (Figure 4). They advised yellow was a very common colour on a ship and, on this occasion, impeded detection of the port‑side handrails during the approach.

Figure 5: Tai Keystone's helicopter landing site viewed from the bridge

Image source: helicopter pilot in command

Touchdown position

The Civil Aviation Safety Authority Advisory Circular 139 Guidelines for heliports – design and operation required that an HLS had a helicopter touchdown/positioning marking (TDPM) as follows:

The objective of touchdown/positioning marking (TDPM) is to provide visual cues which permit a helicopter to be placed in a specific position such that, when the pilot’s seat is above the marking, the undercarriage is within the load bearing area and all parts of the helicopter will be clear of any obstacles by a safe margin.

Where there was no limitation on the direction of touchdown/positioning, a touchdown/positioning circle (TDPC) should be used instead. The line width should be at least 1 m.

On this occasion, the helicopter was positioned with the pilot’s seat over the centre of the white ‘H’, rather than as required with the pilot’s seat above the yellow TDPC (Figure 5).

Marine pilot transfer procedures

Helicopter procedures

The operator’s exposition provided the following information on a typical transfer procedure:

…Descend to 500 ft for a recce[8] to confirm wind, obstructions and approach options.

It also stated that this could be amended to suit the variables of weather, pilot experience, type of ship and whether it is day or night.

The exposition also stated that:

- The safety of the helicopter remains at all times the responsibility of the helicopter pilot in command…

- On arrival overhead or approaching each ship a reconnaissance (recce) should be flown. During this recce or circuit, a careful assessment must be made of the relative wind over the deck with particular attention paid to possible obstructions such as stanchions and cranes, etc… For some transfers, several orbits or an approach with overshoot may be required to obtain sufficient information.

- Pilots should exercise caution on final to look for seamen or deck hands who may be in a position on the deck to approach the landing hatch from behind. Look for ladders and/or handrails during the recce and on final. They will have good intention in trying to assist the marine pilot exiting the helicopter but are often over enthusiastic and unaware of the dangers associated with the tail rotor. Therefore, attempt to keep the tail clear of ladders leading to the hatch from the surrounding deck…

The operator advised they did not maintain a database of ships that they regularly worked with, nor did they require the ship operators to provide a copy of the HLS certification. However, prior to each transfer the ship’s master was required to complete a form designed to identify hazards. If any hazardous items were identified, they were to be photographed and the images added to the form. These forms were provided to pilots prior to departure.

The ship’s master completed this form and did not identify any hazards that increased risk for this vessel. Specifically, they advised there were no obstructions higher than 30 cm on the landing hatch.

Vessel procedures

The Hay Point port procedures required that the ship’s master complete a form to show that the ship complied with the Hay Point port procedures. This form was completed and signed by the ship’s master on 19 November 2023 and indicated that there were no obstructions higher than 30 cm on the landing hatch. The form also indicated that the ship would comply with the International Chamber of Shipping Guide to Helicopter/Ship Operations, as per Marine Order 57 (see the section titled International Chamber of Shipping Guide to Helicopter/Ship Operations).

The vessel’s crew completed a helicopter/ship operation safety checklist on 7 December at 0925, prior to the helicopter’s landing. The checklist revision date was 2017 and referenced the International Chamber of Shipping Guide to Helicopter/Ship Operations, for further guidance. This checklist did not include an item to remove handrails/stanchions.

International Chamber of Shipping Guide to Helicopter/Ship Operations

The International Chamber of Shipping Guide to Helicopter/Ship Operations, fifth edition was published in June 2021, the checklist provided in the fifth edition of the guide included:

- Side rails and, where necessary, awnings, stanchions and other obstructions have been lowered or removed.

The guide also included the following additional considerations for helicopter operating areas.

Chapter 4.3.1 General guidance on markings

The recommended colours of the markings reflect current international standards and best practices and promote a standardised approach to helicopter landing area markings. But as the colour of the main deck may vary from ship to ship, there is some discretion in the selection of deck paint schemes, the objective always being to ensure that the markings show up clearly against the surface of the ship and the operating background.

Chapter 4.5 Additional considerations for helicopter operating areas

- Any handrails that exceed the height limitations set out in section 4.1.2 are made retractable, collapsible or removable and do not obstruct access/exit routes. These handrails should be painted in a contrasting colour scheme and procedures should be in place to retract, collapse or remove them before the helicopter arrives.

- Obstructions close to or inside the operating area, which may present a hazard to helicopter operations, need to be readily visible from the air and should be highlighted. Painting of obstructions should follow the scheme set out in Chapter 9 and Appendix E, as appropriate.

Chapter 9.5 Centreline/amidships helicopter landing/operating area plan included a procedure which should be followed when indicating obstructions on the operating area plan.

1. Red and white stripes should be used to mark the location of notifiable objects in either the central clear zone or the obstacle free sector for the breadth of the ship deck…

- Objects in the central clear zone of height exceeding 2.5 cm; and

- Objects around or outside the central clear zone but in the obstacle free sector described as the funnel of approach for the breadth of the ship’s deck of height exceeding 25 cm.

2. Yellow should be used for marking the position of objects in the forward and aft limited obstacle sectors for the width of the ship’s deck to which the attention of the helicopter pilot should be drawn.

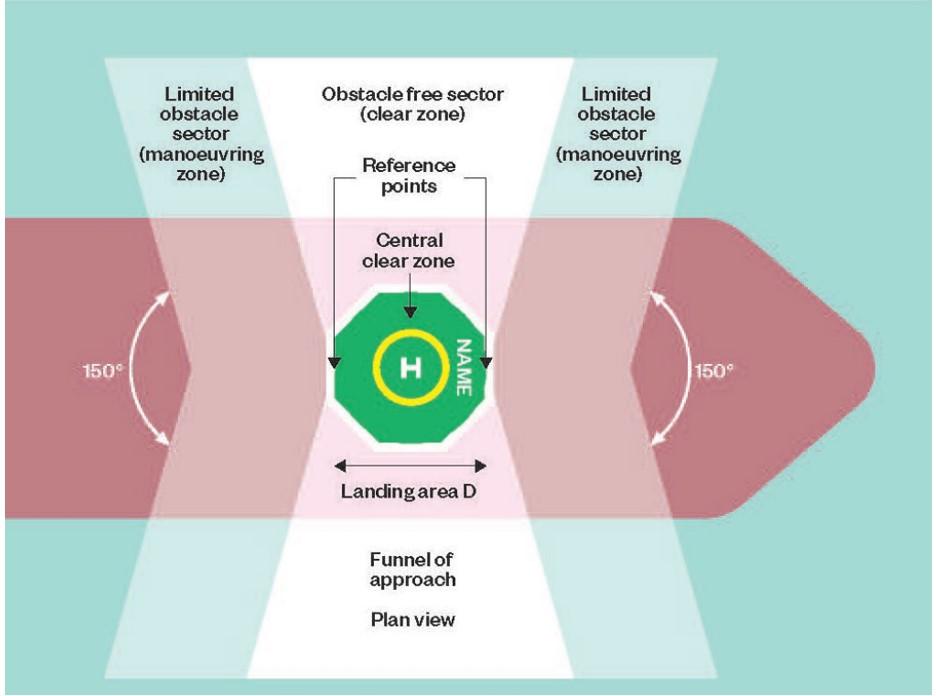

The port‑side handrails were within the obstacle free sector (clear zone) (Figure 6). The clear zone is required to be free of obstacles that present a risk to the helicopter operation.

Figure 6: Landing area terminology

Image source: Civil Aviation Authority UK Civil Aviation Publication 437

Civil Aviation Authority of United Kingdom, Civil Aviation Publication 437

The Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) of United Kingdom published Civil Aviation Publication 437 (CAP 437) Standards for offshore helicopter landing areas. This publication has become an accepted worldwide source of reference for assessing offshore helicopter landing areas.

The CAP 437 provides the same guidance as the International Chamber of Shipping guide for handrails detailed above.

Civil Aviation Safety Authority, Advisory Circular 139

The Australian Civil Aviation Safety Authority published Advisory Circular (AC) 139 Guidelines for heliports design and operation. The AC guidance stated there should be no objects greater than 25 cm or that present a threat to the safe operation of the helicopter on the HLS. However, it did not discuss removable objects, nor a colour to ensure they were visible if accidently left in place.

Australian Marine Safety Authority, Marine Order 57

The Australian Marine Safety Authority, Marine Order 57 specifically defined the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) guide as the Guide to Helicopter/Ship Operations, fourth Edition (2008), published by Marisec Publications, London, on behalf of the ICS. The fifth edition of this guide was released in June 2021, however Marine Order 57 was not amended to reflect the latest updated/improved document.

Safety analysis

The marine pilot advised that they detected the handrails installed on the helicopter landing site (HLS) and instructed a crew member to remove them prior to the helicopter arriving. The helicopter pilot also advised that only one set of handrails was in place when they landed. As such, it is possible that when the instruction was given to remove the handrails:

- one set of handrails was installed, and these were not removed, or

- 2 sets of handrails were installed, and only one was removed.

The ship’s crew were using an outdated version of the International Chamber of Shipping Guide to Helicopter/Ship Operations checklist, which did not include a specific check for handrails or stanchions. While the ATSB could not identify if the checklist had been completed prior to the marine pilot detecting the installed handrails, it is likely that if the vessel was using the most current version, which included a specific item to check for handrails and stanchions, it would have required a member of the vessel’s crew to actively check the handrails and consequently they would have been removed.

The communication between the helicopter and vessel did not include information regarding obstacles, and because no obstacle information was passed to the helicopter pilot, they believed the HLS would be safe to land on. During the helicopter’s approach to the HLS, the helicopter pilot completed a reconnaissance at 300 ft, which provided an opportunity to identify the obstacle. However, as the handrails were an unusual method of accessing the HLS and due to their size, shape and colour, it is likely they would have been difficult to detect. Since the starboard‑side handrails were not installed, once the pilot aligned the helicopter with the final approach path to the landing site, there were no visual cues alerting them to the possibility that the port‑side handrails had not been removed.

The pilot of the helicopter stated they were aware of the red hatch cover obstacles inside the landing site and decided to avoid them by positioning the helicopter clear of the covers. Consequently, the aircraft was positioned with the pilot’s seat over the white ‘H’ instead of the yellow touchdown/positioning circle. This position put the tail rotor slightly outside the obstacle free sector and resulted in contact with the railing.

The International Chamber of Shipping guide provided guidance that removeable handrails should be painted in a contrasting colour scheme, however it did not identify what the colour should be contrasting with. The guide advised that:

- objects in the forward and aft limited obstacle sector should be painted yellow (the handrails were not in this zone)

- notifiable objects in the obstacle free sector exceeding 25 cm should be marked in red and white stripes.

However, despite the handrails being within the obstacle free sector, as they were removable, they were not notifiable objects. In addition, the HLS surface was painted green with yellow markings and, the environment surrounding the handrails, including the permanent ladder leading to the handrails, consisted of items which were also mostly painted in yellow. As such, the yellow handrails did not visually stand out to the helicopter pilot.

The helicopter operator’s exposition provided a warning for pilots relating to seamen installing the handrails prior to a helicopter landing. While the main concern was ensuring seamen did not enter the HLS, this indicated that handrails were a known threat. The helicopter pilots were not always provided with a visual representation of HLSs prior to departure. However, they did receive a form completed by the ship’s master which identified if obstacles were present. Often, the first time they saw the landing site was on arrival overhead the vessel, which limited the opportunity to assess possible threats. Despite this, because the handrails were not a notifiable object, it is unlikely that they would have been included in any guidance of the HLS.

The Civil Aviation Safety Authority published Advisory Circular (AC) 139 Guidelines for heliports ‑ design and operation however, when compared with the United Kingdom (UK) Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) Civil aviation publication (CAP) 437 Standards for Offshore Helicopter Landing Areas, it lacked guidance relating to the colour of obstacles inside the HLS clear zone. AC 139 did not encompass the most current guidance available.

As the Tai Keystone was using the guidance from the International Chamber of Shipping guide, despite it being an earlier version, the lack of information in AC 139 was not considered to have contributed to the incident.

The Australian Marine Safety Authority, Marine Order 57 specifically referenced the International Chamber of Shipping guide, however it referred to a superseded version.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. Safety issues are highlighted in bold to emphasise their importance. A safety issue is a safety factor that (a) can reasonably be regarded as having the potential to adversely affect the safety of future operations, and (b) is a characteristic of an organisation or a system, rather than a characteristic of a specific individual, or characteristic of an operating environment at a specific point in time. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the ground strike during a marine pilot transfer, involving an Agusta A109, VH-RUA and ship Tai Keystone, about 240 km north‑east of Mackay Airport, Queensland on 7 December 2023.

Contributing factors

- During preparation for the helicopter’s arrival, the port side handrails were not removed.

- Prior to the approach, the pilot did not detect the obstacle on the helicopter landing site.

- During the landing, the pilot's seat was not positioned over the touchdown/positioning circle resulting in the tail rotor being outside the obstacle clear sector and striking the handrail.

- An earlier version of the helicopter operations checklist was used by the crew of the Tai Keystone. That checklist did not include a requirement, present in the version current at the time of the incident, to remove handrails or stanchions from the helicopter landing site. [Safety issue]

- The colour of the handrails did not comply with the guidance material provided by the International Chamber of Shipping guide, which increased the difficulty for the helicopter pilot to detect them.

Other factors that increased risk

- The Civil Aviation Safety Authority Advisory Circular 139 Guidelines for heliports – design and operation did not include guidance material for the marking of objects, except for wind direction indicators, located on the helicopter landing site.

- The Australia Maritime Safety Authority Marine Order 57 – Helicopter operations, defined the International Chamber of Shipping guide as the fourth edition published in 2008. This was not the latest improved/updated version of the guidance material.

Safety issues and actions

|

Central to the ATSB’s investigation of transport safety matters is the early identification of safety issues. The ATSB expects relevant organisations will address all safety issues an investigation identifies. Depending on the level of risk of a safety issue, the extent of corrective action taken by the relevant organisation(s), or the desirability of directing a broad safety message to the marine industry, the ATSB may issue a formal safety recommendation or safety advisory notice as part of the final report. All of the directly involved parties were provided with a draft report and invited to provide submissions. As part of that process, each organisation was asked to communicate what safety actions, if any, they had carried out or were planning to carry out in relation to each safety issue relevant to their organisation. Descriptions of each safety issue, and any associated safety recommendations, are detailed below. Click the link to read the full safety issue description, including the issue status and any safety action/s taken. Safety issues and actions are updated on this website when safety issue owners provide further information concerning the implementation of safety action.. |

Helicopter operations checklist

Safety issue number: AO-2023-059-SI-01

Safety issue description: An earlier version of the helicopter operations checklist was used by the crew of the Tai Keystone. That checklist did not include a requirement, present in the version current at the time of the incident, to remove handrails or stanchions from the helicopter landing site.

Safety action not associated with an identified safety issue

Proactive safety action taken by Jayrow Helicopters

| Action number: | AO-2023-059-PSA-03 |

| Action organisation: | Organisation name: Jayrow Helicopters Pty. Ltd. |

| Action status: | Closed |

Following this occurrence, Jayrow Helicopters amended their procedures to ensure that helicopter pilots were provided with images of each individual vessel helicopter landing site prior to departure. They were also developing a new pilot checklist that included a requirement to ensure no obstacles existed within the helicopter landing area.

Proactive safety action taken by Australian Maritime Safety Authority

| Action number: | AO-2023-059-PSA-04 |

| Action organisation: | Organisation name Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) |

| Action status: | Closed |

AMSA noted the reference in Marine Order 57 to the 2008 edition of International Chamber of Shipping Guide, not the updated edition 2021. They advised that this outdated information would be noted for correction in its planned review of Marine Order 57.

Glossary

| AMSA | Australian Maritime Safety Authority |

| CAA | Civil Aviation Authority (United Kingdom) |

| CASA | Civil Aviation Safety Authority |

| HLS | Helicopter landing site means an aerodrome, including a heliport, intended for use wholly or partly for the arrival, departure or movement of helicopters. |

| IMO | International Marine Organisation |

| TDPC | Touchdown/positioning circle |

| TDPM | Touchdown/positioning marking |

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included the:

- helicopter pilot and operator

- marine pilot

- Tai Keystone Master

- spider tracks

- Australian Maritime Safety Authority

References

- International Chamber of Shipping Guide to Helicopter/Ship Operations (5th ed). (2021). London: Marisec Publications

- Australian Reef Pilots Guide. (2013). Australia

- Port Procedures and Information for Shipping – Port of Hay Point. (2017). Australia: Queensland Government

- Marine Order 57 – Helicopter OperationsF2016L00496. (2019). Australia: Australian Maritime Safety Authority

- Civil Aviation Publication 437 - Standards for offshore helicopter landing areas (9th ed). (2023) United Kingdom: Civil Aviation Authority

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority – guidelines for helicopters – design and operation Version 2.0. (2023) Australia: Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Australian Transport Safety Bureau. (2017). Contact with navigation buoy, Navios Northern Star, Torres Strait, Qld on 15 March 2016. MO-2016-003

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- helicopter pilot

- helicopter operator

- marine pilot

- vessel operator

- Tai Keystone Master

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Australian Maritime Safety Authority

Submissions were received from:

- the vessel operator

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2024

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this report is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. The CC BY 4.0 licence enables you to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon our material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] Marine pilot is an expert in navigating a ship through specific waters.

[2] Roll: describes the degree to which the vessel tilts from one side to the other about the longitudinal axis.

[3] Master: the person who has command or charge of a vessel, but does not include a marine pilot.

[4] Helicopter landing site: means an aerodrome, including a heliport, intended for use wholly or partly for the arrival, departure or movement of helicopters.

[5] Stanchion: An upright pole or bar.

[6] Starboard: The nautical term for the right side of a vessel

[7] Port: Port is a nautical term for left side of the vessel.

[8] Recce: shortened term for a reconnaissance or inspection