Executive summary

What happened

On 20 July 2022, during planned track maintenance work, a track mounted excavator toppled when lifting an infrastructure trailer off the track near the Evandale Road level crossing, Evandale, Tasmania. The operator of the excavator was fatally injured and the spotter working with the excavator received minor injuries.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that, while conducting maintenance work, a track mounted excavator was being used to lift an infrastructure trailer when it became unstable and toppled laterally onto the adjacent ground. The operator, who was the site supervisor, was subsequently fatally injured by the excavator.

It was also identified that the total load being lifted, in combination with the configuration of the excavator, meant that the lift was overweight for the displayed civil and hi-rail modes.

While the site supervisor was trained and qualified to operate the excavator, it was likely that they had limited experience and familiarity with this specific excavator. This, combined with a perceived sense of urgency with the work task, resulted in the incorrect configuration being selected for the lift.

During the lift, the spotter placed themselves in a dangerous location between the excavator and infrastructure trailer. When the excavator toppled, the spotter was glanced by the boom on their back. The position of the spotter increased the risk of a more serious injury.

Further, based on the available signage within the excavator being used, it was very likely that the excavator was regularly exceeding the working load limit in both civil and high-rail mode for the planned maintenance work, increasing the risk of instability.

What has been done as a result

TasRail, as the infrastructure manager with oversight of the principal contractor Global Rail, has taken several safety actions in response to concerns regarding the use of road rail vehicle excavators in rail mode. It immediately implemented an embargo on such usage across its entire network. Subsequently, it convened an industry forum to devise a safe approach for the resumption of excavator operations. This resulted in the creation of a process flow chart for using earth-moving equipment as a lifting device, accompanied by a compliance checklist. TasRail also shared the forum's outcomes with other rail infrastructure managers across Australia and New Zealand.

Safety message

It is critical that equipment is operated by qualified, competent, and experienced operators who actively validate the working load limits before commencing a task. Further, selecting appropriate equipment, fit for purpose, reduces the risk of administrative risk controls becoming a last line of defence.

The investigation

| Decisions regarding the scope of an investigation are based on many factors, including the level of safety benefit likely to be obtained from an investigation and the associated resources required. For this occurrence, a limited-scope investigation was conducted in order to produce a short investigation report, and allow for greater industry awareness of findings that affect safety and potential learning opportunities. |

The occurrence

On the morning of 20 July 2022, track maintenance work, to be conducted by Global Rail, was planned to commence in the TasRail rail corridor between Leighlands Road and Evandale Road, Evandale, Tasmania (Figure 1). At about 0700 local time, prior to commencing work, the work team attended a pre-start safety briefing meeting about the day’s activities, including staying clear of working excavators. The work team consisted of a track protection officer, superintendent, site supervisor, 2 primary excavator operators (using a Doosan and a Hitachi excavator), and general labourers. The pre-start meeting was described by some of the work team as being tense between the supervisor and the primary Doosan excavator operator based on an incident that occurred the previous day.

Following the pre-start safety briefing, planned track maintenance work commenced. The planned track work involved replacing sleepers and rail, using 2 rail mounted excavators with infrastructure trailers, interchangeable excavator head tools, and various other tools and supplies. The Hitachi ZX135US excavator was operating on track near the site meeting point/office at Leighlands Road. The Doosan DX140W excavator was ferrying tools, equipment and supplies using 2 infrastructure trailers coupled by draw bars between the main site staging area at Leighlands Road and throughout the worksite. At some point before the rail ferrying was completed, the work team had begun to unclip the old rail from the sleepers, restricting the excavator’s access to the main site staging area at Leighlands Road.

At about 1005, the primary operator of the Doosan excavator unexpectedly parked the excavator at the secondary site area near the Evandale Road level crossing and departed the worksite. The excavator was parked on the track, with the rail wheels disengaged and retracted, and 2 rail mounted infrastructure trailers attached with draw bars.

Figure 1: Location overview

Source: Google Earth, annotated by the ATSB

The superintendent reported that the site supervisor was concerned about the excavator and 2 trailers remaining on the track, and the limitations it would place on the progress of the ongoing work. Following a short discussion, and before the superintendent could complete that discussion, the site supervisor walked off towards the excavator, asking a labourer to act as spotter on the way.

On arrival at the Doosan excavator, the site supervisor climbed into the cabin and began preparing the machine, including lowering the rail wheels to place the excavator into the hi-rail mode, mounting it on the rails. The spotter disconnected the infrastructure trailer draw bars between the excavator and trailers and placed the draw bar on the trailer.

Based on the previous process used, the spotter explained the lifting process to the site supervisor via the cabin door, which was locked in the open position. Following this, the site supervisor positioned the excavator boom arm above the first infrastructure trailer and tried to hook the lifting chain with the rail threader head (Figure 4). Failing this, the spotter attached the lifting chain to a hook located on the tilt rotator head (Figure 4).

At about 1035, while stationary, the site supervisor used the excavator boom, at or near full extension, to lift the infrastructure trailer loaded with the infrastructure trailer draw bar and timber dunnage. The spotter was positioned between the excavator and infrastructure trailer being lifted. The infrastructure trailer was lifted just above rail level before the load gradually slewed laterally.

The spotter reported that, at some point during the lift and slew, the excavator operator realised that the lift was out of control and immediately lowered the boom arm in an effort to stabilise the excavator and/or to avoid striking the spotter. The spotter recalled the rail threader attachment ramming the infrastructure trailer at this time. The spotter, standing between the excavator and the trailer, immediately evacuated the area as the excavator toppled onto its side (Figure 2). The spotter did not directly witness the topple. The excavator boom arm scraped down the back of the spotter as they evacuated the area, resulting in minor injury.

Figure 2: Accident site

Note: Track curvature is 650 m with an average track cant of about 8 mm.

Source: Tasmania Police, annotated by the ATSB

Following the topple, the spotter walked around the excavator looking for the site supervisor, assuming they had escaped from the cabin as the cabin was empty. A short time later, the remaining work team responded, and the site supervisor was found under the excavator towards the rear, fatally injured. The accident was reported to TasRail, with emergency services attending the site shortly thereafter.

Context

Personnel information

Site supervisor

A review of the Global Rail personnel records identified that the site supervisor was experienced with work on and around the track, held the appropriate and up-to-date qualifications and competencies, and was assessed as medically fit.

The site supervisor received the Doosan DX140W excavator operator competency assessment on 21 February 2022. Based on reports from work colleagues, the site supervisor had operated excavators on-site on an ad hoc basis when required. A work colleague suggested that the site supervisor had about 5-8 hours experience operating the Doosan excavator. It could not be determined if the site supervisor had lifted infrastructure trailers before.

Based on the working roster, information from colleagues, and the post-mortem toxicology results, there was no evidence that fatigue, illicit or prescription drugs, or alcohol likely affected their performance on the day.

Spotter

A review of the Global Rail personnel records identified that the labourer, acting as spotter, had about 2-3 years of experience working on or near the track, held the appropriate and up-to-date qualifications and competencies (including a valid construction white card), and had been assessed as medically fit. The labourer had attended a Global Rail safety briefing for the work and had been used as spotter when lifting infrastructure trailers on many occasions during this work.

Excavator information

The Doosan DX140W wheeled excavator was purchased new by Global Rail with an understanding that the working load limit was sufficient for rail infrastructure works. The excavator was subsequently modified by Melrose Mobile Hydraulics to include the addition of road-rail components and systems. This allowed the excavator to travel on both rails and road. It typically consisted of flanged wheels that engaged the rails, rubber tires for road travel, and a lifting system to raise and lower the excavator between rail and road (civil) modes. The rail wheels provided a longer, but narrower footprint compared to the rubber wheels. As result of the modification, the Doosan working load limits were revised using the Australian Standards, consequently reducing the limits.

The excavator was also equipped with a suspension oscillation lock system, which was designed to secure the upper structure (the part that houses the cabin, engine, and hydraulic systems) in a fixed position during a lift, providing stability and preventing unintended movement. It was also fitted with a red safety lock lever on the driver’s seat, which, when engaged in the horizontal position, activated the controls for operation. It was not fitted with a dynamic weighing system or overweight interlocked controls.

An operation and maintenance procedure document was supplied as part of the delivery process in early 2022, along with a training and competency assessment for operators, which included the site supervisor. The training and competency assessment included use of the road-rail system, narrow gauge operation, and use of the oscillation lock system when lifting. The operation and maintenance documented noted:

The Hi-Rail is designed for travel only on rail lines, if any operation of the boom, arm or attachment is to be performed outside of the rolling stock outline the hi-rail WLL [working load limit] chart must be strictly adhered to.

When the Hi-Rail is deployed the maximum allowable boom load is 1900kg. However, depending on the load centre distance from the excavator, this may need to be reduced so that the rail axle capacities are not exceeded. The front & rear hi-rail capacities are 12500 kg. Extreme care should be applied whenever slewing the machine with consideration given to the mass of any boom load or attachment fitted and the radius of boom/dipper arm, see Appendix A for the Hi-Rail W.L.L chart.

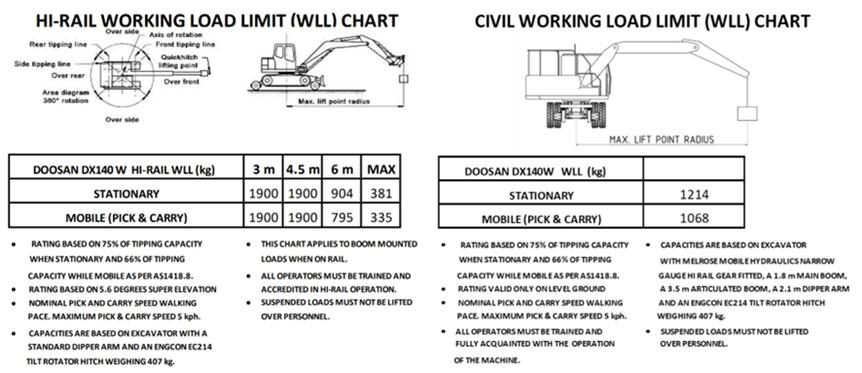

The working load limit chart shows how much weight can be safely lifted at various distances from the centreline (pivot point) of the machine, referred to as the lift point radius. Appendix A from that document, shown below in Figure 3, replicated the working load limit chart sticker located inside the cabin for operator reference.

When in the hi-rail mode, with the boom arm (the lift point radius) fully extended, the maximum weight that could be lifted when stationary was 381 kg. This weight increased to 904 kg with a reduction in the boom arm length to 6 m. When in the civil mode, the lifting capacity was 1,214 kg at any boom arm length. These weight limits reduced when the excavator was moving (mobile) with the load. For both modes, these weights were based on 75% (stationary) and 66% (moving) of the tipping capacity respectively, which is the point at which the machine will begin to tip or lift off the ground.

The capacities presented in the chart are based on the excavator having a standard boom arm and a tilt rotator weight of 407 kg. Therefore, the tilt rotator was excluded from the working load limit weights. The tilt rotator and rail threader are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3: Hi-rail and civil mode working load limit chart

Source: Melrose Mobile Hydraulics Doosan DX140W Excavator Hi-Rail Operation and Maintenance Procedure, 7878 – DX140W HROP – REV 0

Figure 4: Tilt rotator and rail threader

Source: ATSB

Wreckage and site information

Following the accident, TasRail, Global Rail, the Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator (ONRSR), Tasmania Police, WorkSafe Tasmania, and the ATSB attended the site to collect evidence and conduct investigations. The following on-site observations were made by those parties:

- there was evidence of lateral wheel movement (teetering) on the rail head over about 4 m, which correlated with the excavator rear rail wheels (Figure 5)

- the excavator rail wheels were fully lowered in high rail mode

- the suspension oscillation lock was disengaged and selected off in the cabin (Figure 6)

- the boom arm was at or near full extension

- the excavator was fitted with tilt rotator and rail threader attachments

- the infrastructure trailer was connected to the tilt rotator hook via the lifting chain

- the infrastructure trailer had timber dunnage and a draw bar on top

- the cabin door was locked open

- the seat belt was unlatched and retracted

- the red safety lock lever was in the operational (horizontal) position

- there was no evidence of an equipment failure

- the accident occurred on slightly curved track with a post-accident cant measurement of about 17 mm

- the primary Doosan excavator operator and site supervisor had not signed the pre-start briefing sheet, as required

- the other excavator being used, the Hitachi ZX135US (tracked), did not have a working load limit chart sticker in the cabin.

Figure 5: Teetering evidence on the rail head

Source: Tasmania Police, annotated by the ATSB

Figure 6: Oscillation lock disengaged and off

Source: Tasmania Police, WorkSafe Tasmania, ONRSR, annotated by the ATSB

The excavator and associated equipment were further inspected at an off-site Police facility following recovery. The following observations were made by the ATSB:

- The excavator was fitted with a working load limit lift chart sticker, along with other operational stickers, on the boom-side cabin window.

- Other current compliance labels (Global Rail, TasRail) were also identified.

- The boom was labelled ‘W.L.L. [working load limit] 1068KG’ (civil mode, mobile pick and carry).

- The rail infrastructure trailer, draw bar, and lifting chains, were fitted with compliance plates.

- The excavator was not fitted with a rail data recorder or similar, nor was it required to be.

The ATSB also took various measurements that were recorded between the tilt rotator, rail wheels, rubber road wheels, and pivot point.

On 26 July 2022, an ONRSR rail safety officer inspected the excavator at the storage facility, and the accident site. The officer concluded that, aside from accident damage, the excavator was in a good condition with no signs of poor maintenance. It was noted that the excavator’s front rail axle was in travelling mode during the inspection, suggesting it was pivoting rather than locked (suspension oscillation locking system).

The ONRSR officer noted that the accident happened on curved track, where the excavator would have leaned towards the inside due to the track's cant. Evidence such as flange marks and paint scratches indicated that the excavator likely rolled over towards the inside of the curve at a very low speed. ONRSR static overturning calculations indicated that the combination of factors such as the axle mode, track cant, and wheel position alone would not have led to the rollover. However, a significant lateral shift in the excavator centre of gravity, possibly resulting from the operator (site supervisor) rotating the boom, contributed to the rollover.

Stationary load limit calculations

Equipment weights

Table 1 below shows the equipment being used and their individual weights as shown on the respective compliance plates.

Table 1: Equipment weights

| Equipment | Weight (kg) |

| Infrastructure trailer | 1,780 |

| Rail threader | 330 |

| Tilt rotator | 407 (already included in the base weight of the excavator) |

| Draw bar long | 176 |

| Draw bar short | 156 |

Actual working load limit

The excavator was lifting a combined equipment weight of at least 2,266 kg, consisting of the infrastructure trailer, rail threader, and short draw bar. This calculation did not include the timber dunnage or lifting chains.

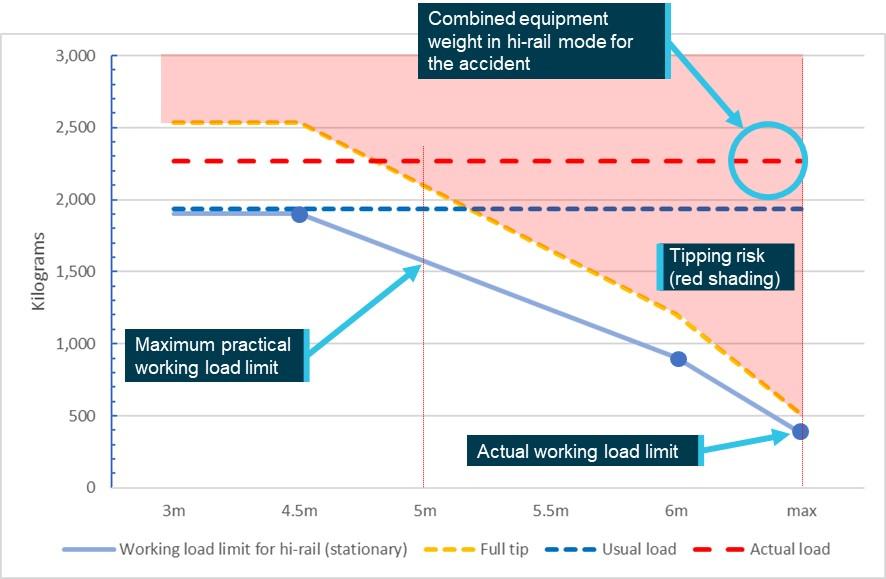

On-site observations indicated the excavator boom arm was at near or full extension. Referring to the lift chart for the stationary hi-rail mode (Figure 3), the maximum working load limit was between 904 kg at 6 m and 381 kg at maximum extension. Given the items being lifted from the track, the excavator was lifting between 1,362 kg (150%) and 1,885 kg (495%) over the working load limit (Figure 7).

The primary operators of both excavators recalled that, when lifting infrastructure trailers, they would normally be in the civil mode, with the boom arm close to the excavator, and without the rail threader being attached. It was reported that the lifting of the infrastructure trailers on and off the track would take place at the main site at Leighlands Road. In this configuration, the excavator would be lifting a combined equipment weight of at least 1,936 kg, consisting of the infrastructure trailer and short draw bar. Based on a working load limit when in the stationary civil mode (1,214 kg), the limit would also have been overweight by 722 kg (61%) without the rail threader installed or 1,052 kg (87%) in the accident configuration (with a rail threader installed).

Practical working load limit

Noting that the working load limit weight reduced as the boom arm was extended, for the Doosan excavator, the ATSB estimated the minimum possible lift point radius that could be achieved when lifting an infrastructure trailer. The ATSB measured between the pivot point and the leading edge of the hi-rail wheels to be about 3 m. The infrastructure trailer was 4 m long, meaning the lift point (in the centre) was 2 m from the trailer edge. This meant that the minimum possible distance from the pivot point to the lift point was about 5 m.

Using the stationary hi-rail mode working load limit chart (Figure 3), the ATSB linearly extrapolated an indicative limit for a 5 m extension or lift radius as 1,568 kg.[1] This meant that, at the closest possible distance, the excavator would be lifting 698 kg (45%) above the working load limit (with an empty trailer, rail threader and short draw bar, similar to the accident (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Combined equipment weight, working load limit, lift point radius (boom arm extension), and tipping capacity for hi-rail mode

Source: ATSB

For comparison, and as noted above, the civil working load limits remained the same irrespective of the boom arm extension. Therefore, for the normal operating configuration as reported by the primary operators, it would be 722 kg (61%) overweight (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Combined equipment weight, working load limit, lift point radius (boom arm extension), and tipping capacity for civil mode]

![Figure 8: Combined equipment weight, working load limit, lift point radius (boom arm extension), and tipping capacity for civil mode]](/sites/default/files/styles/wide/public/2024-10/RO-2022-008-Figure%208.jpg?itok=aKEnvCvK)

Source: ATSB

TasRail comment

In response to this draft report, TasRail noted that thought should be given to having a separate industry standard or guidance regarding the use of road-rail vehicle equipment as a lifting device. This could include consideration of:

- the risk profiles of different track gauges

- the requirement for operators to conduct a detailed risk assessment and calculations prior to the deployment of such equipment where its capacities change depending on the task or environment, for example, when used in civil or hi-rail modes

- the human factors associated with swapping between modes of operation

- the possible control measures of limiters and alarms, for example, overlimit interlocking systems or overlimit alarms.

TasRail also noted the importance of conducting a risk assessment to ensure fit for purpose equipment is procured and/or used.

Track work

The rail work being conducted at Leighlands Road was part of a larger scope of work in that rail corridor, and included replacing sleepers and rail, and removal of fouled ballast (mudholes) and associated re-railing and re-sleepering. TasRail, the rail infrastructure manager, had tendered the work, and Global Rail was awarded the contract. To enable the work to be completed efficiently and safely, elements of the work, such as rail and sleeper handling, were mechanised.

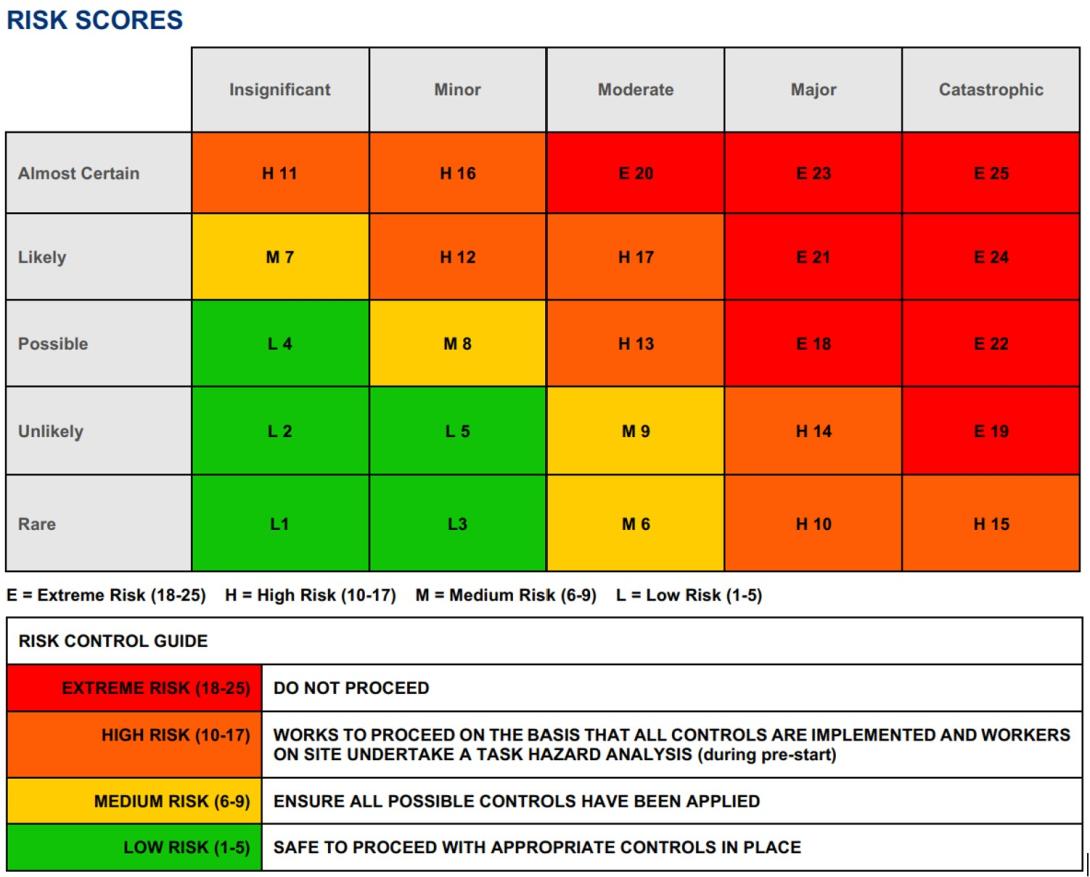

As part of the scope of work, a risk assessment was developed, which identified risks associated with the planned work. To address these risks, a safe work method statement (SWMS 044 dated 07-03-2022, issue 7.0) was developed for the removal and installation of rail and sleepers. In that statement, a plant (such as excavators) hazard risk of rollover was identified. The risk control measures were:

- Plant operator must be ticketed and competent for his item of plant.

- All plant to be fitted with flashing lights and reversing alarms.

- When moving around plant and equipment eye or verbal contact with the operator must be made prior to any personnel entering the danger zone or changing locations.

- Plant operators must not use mobile phones at any time they are operating machinery on the site.

- Visually inspect the terrain to ensure there is no chance of tipping due to potentially hazardous surfaces uneven ground / embankments.

Furthermore, a plant sliding/tipping event during lifting operations was identified, and included the following control measures:

- Ensure level platform before commencing any lifting operations.

- Only operate to the OEM [Original Equipment Manufacturer] of the machine.

- Machine may need to be de rated when used to lift.

- A lift chart must be in the cabin for the operator to refer to.

In addition, lifting outside of the safe working limit (SWL) of plant was identified, and included the following control measures:

- Before commencing a lift check, Max load to be lifted (Delivery docket or Lift Study) SWL of plant and SWL of lifting equipment to ensure lift is within the SWL of all the plant and equipment.

- All plant including chains to display WWL (Working Weight Limit) / SWL (Safe Work Load) signage.

- Plant and lifting equipment used not to exceed registered WWL/ SWL- Only plant rated to load capacities to be used.

The above risks were identified as high inherent 16 (moderate consequence, likely likelihood) with a residual risk of low 5 (minor consequence, unlikely likelihood) after control measures were effectively applied by the site supervisor and operator (Figure 9).

Furthermore, safe work method statement (SWMS006 Operating an excavator, dated 29-04-2022, issue 5.0) was developed for the operation of excavators. The following control measures were identified:

- Working or traversing on sloping ground - No plant or equipment is to work or traverse on slope over designated gradient as outlined in manufacturers user manual. If traversing slope use low gear and ensure that attachments are slewed to the uphill side of the plant and packed in the travel position.

- Working excavator as a crane - Use dogman/rigger if required. Ensure all lifting equipment is inspected prior to use, is appropriate for the task and is within test dates. Check safe working load and condition of equipment prior to activity being undertaken. Safe working load of plant must be identified and load chart referred to for any variances. Inspect excavator and approved lifting lug. Check burst protection fitted for any loads in excess of 1 tonne. At no time will a suspended load be lifted over any persons. Ensure that all workers are outside the extended height and maximum radius of the plant.

The above risks were identified as high inherent 14 with a residual risk of high 10 after control measures were effectively applied. This meant that works could proceed on the basis that all controls were implemented, and workers onsite undertook a task hazard analysis where required. Global Rail advised that the task hazard analysis was contained in the pre-start briefing conducted on the day by the work site supervisor. Excavator operating duties were also assigned to specific individuals at that meeting, however, this was not recorded on the pre‑start briefing form. Global Rail further advised that there was an expectation that any change to those specific assignments would require a new pre-start briefing to be conducted, however, there was no documented evidence provided to support how this expectation was conveyed to the work team.

Figure 9: Risk scores used in Global Rail safe work method statements

Source: Global Rail

Safety analysis

Introduction

On 20 July 2022, a track mounted excavator became unstable and toppled laterally, fatally injuring the operator (the site supervisor). There was no evidence to suggest the site supervisor’s performance was influenced by drugs or alcohol, nor was there any indication of equipment failure that may have contributed to the instability or topple of the excavator.

This analysis will examine the accident sequence and the weight of the load being lifted on this and previous occasions. It will also discuss the position of the spotter during the lift.

Instability and toppling of the excavator

Evidence found on-site showed the rear wheels of the excavator teetered along the rail head, leading up to the excavator toppling. The spotter observed that the site supervisor was in the cabin, with the door latched open, immediately before the excavator toppled. Following the topple, the spotter had assumed that the site supervisor had evacuated as the cabin was found empty. However, the site supervisor was found under the excavator. As the spotter did not witness the evacuation, it could not be determined if the site supervisor either evacuated the cabin during the topple sequence, or was ejected from the cabin during the topple, and subsequently received fatal injuries.

It was also noted that the seatbelt was found unlatched following the accident, but there was insufficient evidence to determine if the operator was wearing the seatbelt at the time.

Lifting overweight and configurations

Based on weight information available within the cabin and on the equipment, and operating at near full boom extension in hi-rail mode, the total weight being lifted was significantly over the working load limits (between 150% and 495% above). This condition very likely contributed to the rear rail wheels of the excavator unloading and teetering along the rail head leading up to the topple. Consequently, the front rail wheels carried the total load, significantly affecting the lateral stability of the excavator and its ability to control the load, shifting the centre of gravity, and pivot point. Further, the suspension oscillation lock on the front axle was disengaged, further reducing lateral stability, and inducing more teetering and lateral load swing. In combination, these conditions resulted in the excavator becoming unstable. This was supported by the ONRSR review of the static rollover calculations, which demonstrated significant lateral shift in the centre of gravity, likely resulting from the slewing of the boom, was required to cause a topple.

Experience, familiarity, and sense of urgency

The superintendent on-site recalled speaking with the site supervisor to solve the issue with the parked Doosan excavator and infrastructure trailers. However, before the superintendent could complete the discussion, the site supervisor had walked off towards the excavator without considering alternative options for removing the trailer. Therefore, it was likely the site supervisor had a sense of urgency to resolve the issue so that they were not delayed.

The training records showed the site supervisor was deemed competent to operate an excavator having completed competency training for the Doosan about 5 months prior to the accident. However, based on information supplied by witnesses, it was likely that the site supervisor had limited practical experience using the excavator and required some advice from the spotter in its lifting operation on the day of the accident. In addition, while the site supervisor had observed the other excavator operators performing similar lifting operations, it was possible that they would not have known the exact lifting configuration, or the weight of the trailers being lifted, on those occasions. Changing the excavator to hi-rail mode demonstrated that the site supervisor had some knowledge of how to operate the excavator, but also showed limited familiarity and experience as this configuration was not appropriate for the lift to be conducted.

Therefore, it was likely that the site-supervisor’s limited experience and familiarity with the Doosan excavator, and a perceived sense of urgency to progress the work task, set up the condition of being in the incorrect configuration, lifting overweight, inducing teetering, and eventually toppling.

Spotter location

The spotter was suitability qualified, trained and had experience with spotting. Further, the spotter had attended a Global Rail safety briefing for the work as well as a pre-start briefing on the day of the accident, which included information about operating near the excavators. Regardless, to communicate with the site supervisor, the spotter had positioned themselves between the excavator and infrastructure trailer. Consequently, this placed the spotter in a dangerous location within the swing radius of the boom. This increased the risk of the spotter receiving more serious injuries.

Working load limits and the planned track work

The Doosan excavator was acquired by Global Rail to assist fulfilling the track work contract with TasRail. Based on local information (stickers and compliance plates) available, there was sufficient information to determine that lifting infrastructure trailers exceeded the working load limit of the Doosan excavator in both civil and hi-rail modes. Further, the use of this equipment was known and planned for during the scoping stage, however, the working load limit exceedance was not identified. Consequently, the Doosan excavator was very likely routinely lifting infrastructure trailers that exceeded the working load limit.

It was possible that the working load limit exceedance had not been identified previously due to the skill and experience of the primary operator, who configured the excavator to maximise its capability. This included lifting in civil mode, with the load as close as possible to the excavator and without the rail threader attached.

It was important, and a requirement of the safe work method statement, that the equipment load was calculated and compared to the working load limit declared in the machine cabin via the load chart. This was to ensure that lifting operations were not outside the safe working load limit, thereby increasing the risk of instability. If the working load limit cannot be determined, then the lift should not occur.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the fatality involving a track mounted excavator, Evandale, Tasmania, on 20 July 2022.

Contributing factors

- During lifting operations, a track mounted excavator became unstable and toppled laterally onto the adjacent ground. The operator (site supervisor) was subsequently fatally injured by the excavator.

- The total load being lifted, in combination with the configuration, meant that the lift was overweight for the displayed civil and hi-rail modes. This resulted in the rear rail wheels lifting and the excavator becoming unstable.

- While trained and qualified, it was likely that the site supervisor’s limited experience and familiarity with this specific excavator, combined with a perceived sense of urgency with the work task, resulted in the incorrect configuration being selected.

- During the lift, the spotter was situated in a location between the excavator and infrastructure trailer, which increased the risk of a more serious injury.

Other factors that increased risk

- Based on the available signage within the excavator being used, which was one of the control measures for managing the risk of tipping and/or lifting equipment beyond the working load limits, it was very likely that lifting infrastructure trailers exceeded the working load limit in both civil and high-rail mode, increasing the risk of instability.

Safety actions

| Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence. |

Safety action by TasRail

Since the occurrence, TasRail has undertaken a number of proactive safety actions, including:

- TasRail immediately implemented a self-imposed embargo on all RRV [rail road vehicle] excavator use whilst in rail mode across the entire network.

- Conducted an industry forum to determine a path forward for the safe return of excavator operations, and a process was developed to ensure that contractors /operators could assure themselves of the safety of their employees and equipment.

- The output of the forum was the development of a process flow chart for the use of “Earth Moving Equipment Being used as a Lifting Device”. A supporting checklist was also developed to allow monitoring of compliance.

- TasRail has proactively shared the outcomes of the industry forum with other rail infrastructure managers throughout Australia and New Zealand.

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- witnesses

- Global Rail

- Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator

- TasRail

- Tasmania Police

- WorkSafe Tasmania.

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- Global Rail

- TasRail

- Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator

- labourer acting as spotter.

Submissions were received from:

- Global Rail

- TasRail

- Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator.

The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2024 Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this report is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. The CC BY 4.0 licence enables you to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon our material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] This calculation assumed that there was a linear reduction in the working load limit with an increasing lift point radius.