Executive summary

What happened

On 27 February 2022, south-east Queensland and the Port of Brisbane were in the grip of a significant weather and flooding event that exceeded the initial forecasts. The Brisbane River was in flood and a persistent ebb flow, with the downriver current increasing as rain continued to fall and large volumes of water continued to enter the river. The oil products tanker, CSC Friendship, was berthed at the Ampol products wharf in the river and had completed loading of about 32,000 tonnes of petroleum products bound for other Australian ports.

At about 2250 local time, the downriver current was flowing at 4.5 knots when CSC Friendship’s mooring arrangement capability was exceeded. Mooring lines parted, winch brakes slipped, and the ship surged down the wharf. Despite the efforts of the ship’s crew, including release of the outboard anchor and the swift attendance of 2 tugs, the ship broke away from the wharf. The current swept the ship across the channel and it grounded 400 m downstream, on the opposite side of the river.

At about 0105 on 28 February, following a request by the Brisbane vessel traffic service, a port pilot boarded the ship to assist recovery. The ship remained fast aground until it refloated at 0500. During the subsequent recovery, with 3 tugs assisting, an attempt was made to retrieve the anchor. Heaving in the anchor led to the ship veering across the channel and grounding on the other side of the channel, downstream of the wharf and close to Clara Rock, a charted hazard. The anchor was then slipped, and the ship manoeuvred clear of Clara Rock. Subsequently, the pilot safely conducted the ship downriver into Moreton Bay, where it anchored.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that the deteriorating conditions exceeded those initially forecast but that the associated increased safety risk to shipping and the port was foreseeable. The Bureau of Meteorology had issued numerous warnings of the impending event spanning the greater Brisbane River catchment area from 21 February, which provided sufficient information to identify and assess the increased likelihood of a breakaway. The current in the river exceeded operational limits for both the berth and the ship’s mooring arrangements for more than 14 hours prior to the breakaway.

The investigation identified that Maritime Safety Queensland (MSQ) did not have structured or formalised risk or emergency management processes or procedures. Consequently, MSQ was unable to adequately assess and respond to the risk posed by the river conditions and current to ensure the safety of berthed ships, port infrastructure or the environment.

The ATSB also identified that Poseidon Sea Pilots (PSP), the port’s pilotage provider, did not have procedures to manage predictable risks associated with increased river flow or pilotage operations outside normal conditions. This, in part, resulted in PSP not considering risks due to the increased river flow properly and not taking an active role until after the breakaway.

It was also found that Ampol, the wharf operator, had not considered the risk to the ship or the wharf due to increased river flow.

What has been done as a result

Maritime Safety Queensland made significant changes to operations and systems in response to this incident and flood event. The changes included:

- policy and procedural updates including:

- emergency and contingency planning and response, including developing a port flood evacuation guideline and extreme weather aids

- revisions to contingency plans and the port procedures manual

- adoption of the Australian Warning System for marine weather events

- capital improvements, including:

- installation of 3 additional current meters in the river

- provision of public access to real-time port weather information, including current meters

- involvement with multiple investigations and analyses of the incident, river conditions, port operations (mooring studies, ship manoeuvring) and contingency planning

- engaging with multiple port stakeholders, facility owners and other parties to better improve collaborative planning for and response to extreme weather events including river flood

- establishing a distinct management role to lead a dedicated Maritime Emergency Management team to support the Incident Controller in managing an incident.

Further, MSQ required pilots to complete simulator training for manoeuvring ships in high water current conditions.

Poseidon Sea Pilots (PSP) has taken various safety actions, which included collaborating with MSQ to develop emergency evacuation procedures to respond to increased river flow and document them in its pilotage operations safety management system (POSMS). In addition, PSP provided input for changes to MSQ’s standard port procedures.

Other action by PSP included developing emergency evacuation procedures with MSQ using its bridge/ship simulator and documenting several such procedures for berths, including the Ampol products wharf, in its POSMS. All its pilots are now required to undertake at least one emergency evacuation procedure in the simulator as part of continuous professional development.

The POSMS was amended to include an ‘extreme weather event’ section to provide general information and guidance and all pilots were provided MSQ’s Brisbane port evacuation guidelines. An emergency response procedure introduced to the POSMS describes aspects of emergency management and states that MSQ’s regional harbour master will manage port emergencies with PSP’s support.

Ampol advised the ATSB that it had conducted an incident investigation and an analysis of mooring arrangements and limitations for ships berthed at the products wharf in increased current speed. Based upon this study, Ampol developed a Product Wharf Safe Operating Envelope document which specified wharf operational limits and response actions for varying wind and river speeds.

The ATSB assessed the safety action taken by all parties in response to the identified safety issues. This assessment indicated that the action taken by MSQ, while significant, did not fully address the issue with respect to its risk management processes or procedures to manage any type of emergency. Therefore, the ATSB has issued a recommendation to MSQ to take further safety action.

Safety message

As this breakaway illustrates, port infrastructure and associated shipping can be exposed to dynamic hazards, which include the inherent uncertainty of weather forecasts. The safe management of such situations requires clearly defined emergency and risk management arrangements which include an accurate assessment of all the available information by the involved parties with a willingness to err on the side of safety where doubt exists.

The emergency response process can be significantly aided by a structured process to present the relevant information in a usable format to those tasked with assessing and responding. Then, as the risk increases, coordinated and timely decisions can be made using established processes, including trigger points, priority lists, and escalation and contingency plans and procedures for an effective response to the emergency.

The occurrence

Weather event

Significant rain in south-east Queensland during February 2022 resulted in the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) issuing an initial flood watch on 22 February for possible minor to major flooding in catchments (areas where water collects), including the upper and lower Brisbane River. The following day an initial minor flood warning was issued for rivers upstream of Somerset and Wivenhoe dams (in the upper Brisbane River catchment). The warning indicated that the weather system was likely to produce areas of heavy to intense rainfall and thunderstorms over south-east Queensland. The BoM also advised that, as catchments were already wet, this additional significant rainfall was likely to quickly result in surface run‑off.

As the weather system approached south-east Queensland and the Port of Brisbane, awareness of the situation increased, and local and district emergency management agencies were put on alert. The regional harbour master (RHM)[1] for the Port of Brisbane, having assessed the situation at that time, concluded that the weather event would likely affect an area north of Brisbane and the port.

On 24 February, debris was observed in the Brisbane River. The pilot manager of Brisbane’s port pilotage service provider, Poseidon Sea Pilots (PSP), was concerned that the river flow could affect shipping movements in the river and reported raising this with the RHM but believed that movements were still feasible at that time.

Early on 25 February, BoM started issuing moderate, and then major, flood warnings for the upper Brisbane River (above Wivenhoe Dam). At 1635 local time, BoM issued the initial (minor) flood warning for the lower Brisbane River[2] advising of possible flooding over the following days (weekend). Agencies across south-east Queensland increased their levels of readiness during the course of the day and multiple warnings and notices were promulgated to prepare for the unfolding situation. From about 1700, the river current (recorded in the port at the 2F beacon)[3] became a continuous downriver flow regardless of whether the predicted tide was flooding or ebbing at the river mouth.[4]

CSC Friendship

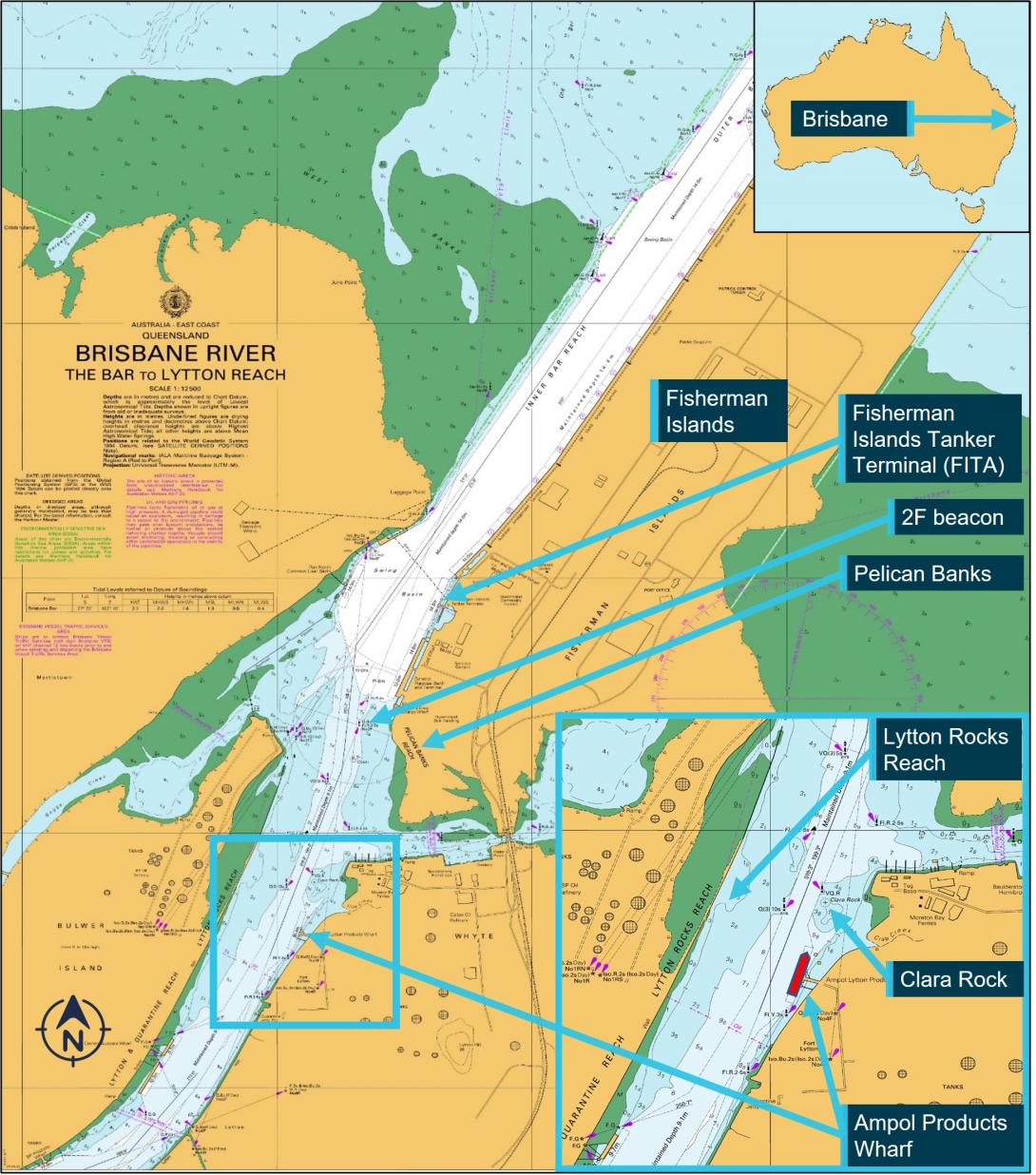

When the continuous downriver flow commenced, the 185 m oil tanker CSC Friendship (cover) was berthed head-down[5] alongside the Ampol[6] Lytton Products wharf in the river (Figure 1) to load diesel and gasoline cargoes. Loading had started at 2000 on 25 February and was expected to be completed early on 27 February, with the ship due to sail at about 0500 that day on the flooding tide.

At about 2230 on 25 February, Brisbane vessel traffic service (VTS) notified relevant port stakeholders via email and radio (VHF channel 12) that BoM had issued a ‘severe thunderstorm’ warning with very dangerous thunderstorms and intense rainfall expected in the area, including the port.

Figure 1: CSC Friendship’s location at the Ampol products wharf

Vertical chart gridlines are at one minute of latitude.

Source: Australian Hydrographic Office, annotated by the ATSB

At about 0615 on 26 February, a minor flood level was reached in the river at Brisbane City. At about 0800, the RHM consulted the manager vessel traffic services (MVTS) and the Maritime Safety Queensland (MSQ) duty area manager to further assess the situation. Shortly thereafter, at 0830, the RHM issued the first MSQ situation report in relation to the weather event.

At that time, the port was open and there were ship movements in and out of Fisherman Islands berths. MSQ advised all concerned port stakeholders of disruptions to port operations and the shipping schedule, especially above Pelican Banks (river berths). All berthed ships were advised to check their mooring lines and put out additional lines. Additionally, 3 harbour tugs were placed on standby and available for immediate deployment.

Meanwhile, CSC Friendship’s cargo loading progressed and the ‘Ampol marine movements specialist’[7] (Ampol marine specialist) arranged for the ship’s departure, including booking a pilot and tugs for its scheduled sailing time.

At 1157 on 26 February, MSQ advised the Ampol marine specialist that the port was likely to close due to the deteriorating conditions. As the port’s closure would prevent CSC Friendship departing and disrupt Ampol’s fuel supply services to other Australian ports, the Ampol marine specialist decided to change the loading plan of the ship so it could depart earlier. The departure time tidal windows would need to be after high water to minimise the ebb flow with the ship berthed head‑down. The first tidal window was around the high tide at about 1800 that day and a request was made to depart at that time.

As ship movements were being affected by the fast-flowing ebb current in the river, the RHM consulted the pilot manager who visually checked the current and advised that it was about 4 knots. Subsequently, the pilot manager, together with another experienced pilot, considered the risks of moving CSC Friendship. Their considerations were largely based on MSQ’s standard procedures, which prohibited ship departures from the Ampol products wharf during an ebb flow. They concluded that, in the prevailing ebb flow and considering the proximity of Clara Rock to the wharf (about 300 m downstream, see Figure 1), moving the ship presented a greater risk than leaving it there. Additionally, both assessed that the debris in the river did not allow safe ship movements. The 1800 departure was therefore cancelled and, over the following hours, other departure time requests were also declined by VTS.

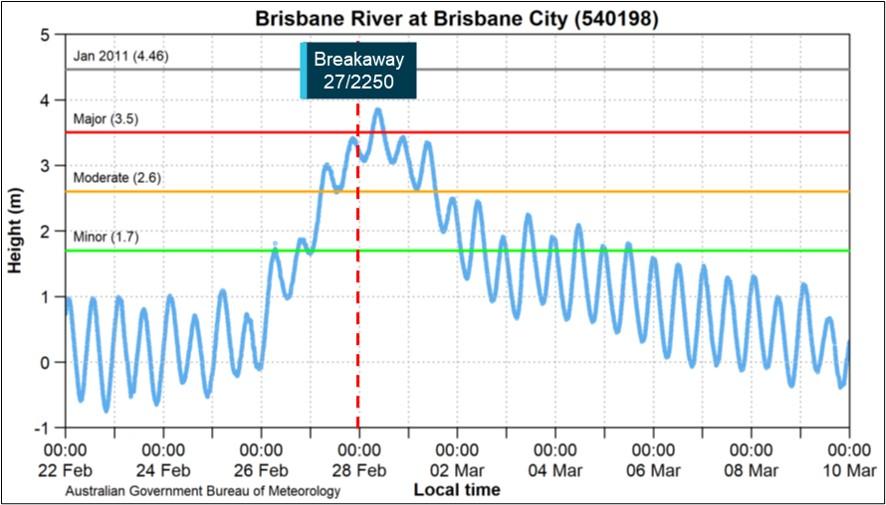

At 1508 on 26 February, BoM issued a moderate flood warning for Brisbane, expected on the morning high tide on 27 February. At about 1750, the river level in Brisbane City was above the minor flood level, and remained above this level until 2 March (Figure 5).

Heavy rainfall continued over the region and BoM issued numerous weather and flood warnings as conditions in the river continued to deteriorate. Port operations were increasingly disrupted, including due to the limited availability of pilots, tug crews and line handlers as the floods affected land transport. All ships were advised to lower an anchor (outboard) to the seabed in addition to taking extra mooring precautions.

At about 1600 that day, the container ship S Santiago broke away from its berth at Fisherman Islands when its mooring lines parted as another container ship was being berthed ahead and upstream of it. S Santiago was resecured alongside its berth at 1630 with tug assistance. At the time, the ship’s master stated that a 20–25 knot wind had pushed the stern away from the wharf resulting in several mooring lines parting.

At 2020, CSC Friendship completed loading (25,000 t of diesel oil and 7,000 t of gasoline) and the ship’s crew went about preparations for departure.

Late on 26 February, after an oil tanker berthed at Fisherman Islands, all shipping movements in the port were suspended at the direction of the RHM.

At 0400 on 27 February the planned release of water from Wivenhoe Dam commenced, with that flow expected to take more than 24 hours to reach the port. Then, at about 0515, the Brisbane River passed the moderate flood level in the city. It remained above this level until after 1300 on 1 March.

At 0600, the Ampol marine specialist boarded CSC Friendship and confirmed that the ship was ready for departure. VTS advised the marine specialist that the port was closed and departure would be rescheduled to a later date. At 0700, all ships in the port were directed to have their main engines on standby (for immediate use).

BoM continued to issue flood and gale force wind warnings for south-east Queensland throughout 27 February. Other authorities, including MSQ, also issued alerts and warnings for their areas of responsibility. At 1813, BoM issued a major flood warning for the Brisbane River.

Breakaway and grounding

At about 2250 on 27 February, the crew of CSC Friendship felt a sudden surge through the ship. A short time later, the centre aft stern line, secured on bitts,[8] parted. This increased the load on the 13 remaining mooring lines. In response, the crew quickly mustered, powered up the ship’s mooring winches, and prepared to bring the ship’s main engine online.

The ship’s mooring winch brakes slipped[9] under the increased load and the ship picked up momentum and surged downstream along the berth. One forward spring line, 2 aft spring lines and an aft breast line parted a short time later. The ship continued to move downstream, causing the gangway to strike the ‘marine loading arm’ (oil transfer arm or boom) before falling away from the ship’s side onto the wharf.

The ship came to rest about 90 m further down the berth with the aft one third of it resting on the wharf pads and secured only by the 9 remaining mooring lines.

At 2254, the master contacted VTS and requested permission to let go the port anchor. Following receipt of permission, the anchor was released with 4 shackles[10] of chain on deck. At 2258, the master again called VTS and urgently requested tug assistance and by 2311 had engaged astern propulsion.

Meanwhile, at about 2300, Brisbane VTS requested the attendance of 2 tugs, which arrived about 12 minutes later and immediately made fast lines: centre lead forward and aft on the port quarter. However, due to the strong river current, the tugs had minimal effect moving the ship and the master called VTS and requested an additional tug to assist. The master was informed that the extra tug would take 30 minutes to get underway. Concurrently, VTS asked for a pilot to urgently attend the ship at the wharf to return it back alongside (as the port was closed, no pilots had been assigned for any movements).

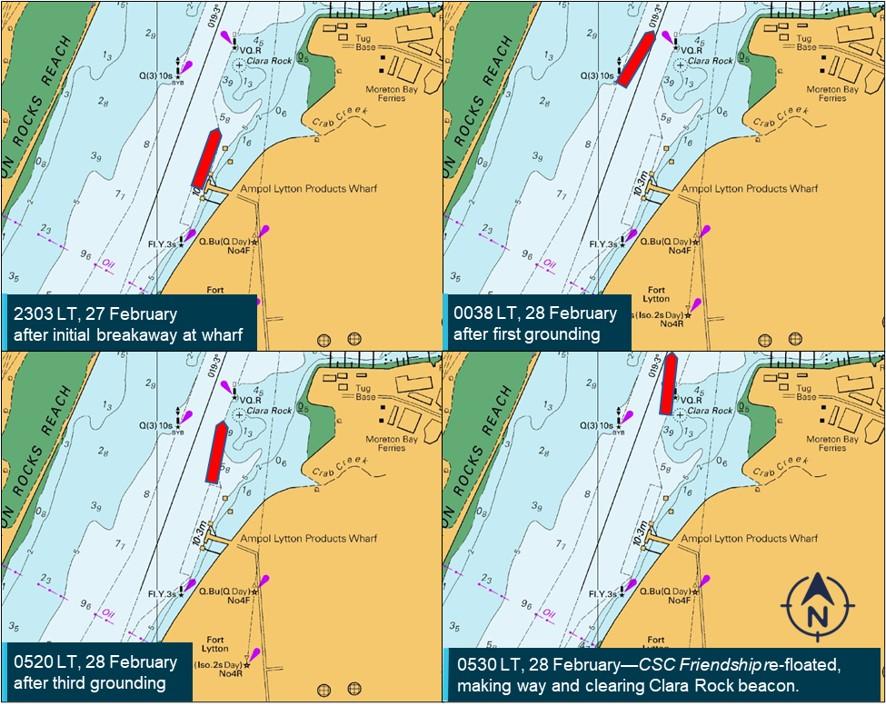

About 0028 on 28 February, with the 2 tugs unable to hold the ship alongside, the remaining mooring lines paid out and CSC Friendship broke free of the berth. The ship was swept downstream by the fast-flowing river, across the channel and grounded east of Clara Rock beacon at Lytton Rocks Reach (Figure 2). A short time later, the additional tug, arrived.

Figure 2: CSC Friendship aground at Lytton Rocks Reach with tug in attendance

Source: Svitzer

Subsequent groundings

About 0105, the pilot arrived by launch and boarded the grounded ship via the ship’s pilot ladder. The pilot quickly established the ship was aground with its port quarter on the bank, bow slightly in the channel and head down river. The pilot estimated the river current was 5 to 6 knots from astern and that it was effectively pushing the ship onto the bank. Further, the port anchor had 6 shackles of chain paid out. The chain had fouled over the ship’s bulbous bow and was leading astern on the starboard side, and back towards the wharf.

The pilot conducted a briefing with the masters of the ship and the assisting tugs. Then, at about 0150, the pilot attempted to free the ship using a combination of 2 tugs pulling the ship’s stern to starboard, heaving on the anchor, and running the main engine astern. By 0210 it became evident that the ship had not moved and remained aground at Lytton Rocks Reach (Figure 3, top right). In response, the pilot stopped the engine and stood down the tugs with one directed to remain on station. The other tugs returned to the tug base to manage crew fatigue prior to returning at high tide.

Figure 3: CSC Friendship’s position (red) at key times

Source: Australian Hydrographic Office, annotated by the ATSB

At 0500, while it was still dark, the pilot estimated the ebb current flow had decreased to roughly 3 or 4 knots and requested the tugs to make fast to the ship to attempt another move. The port anchor remained a concern for the pilot and, after discussion with the master (who was consulting the ship’s managers ashore), the pilot agreed to the request to retrieve the anchor without compromising the re-floating attempt. Ten minutes later, the pilot instructed both tugs aft to lift off using full power and move out to starboard to bring the ship’s stern towards the channel.

The stern of the ship immediately started to move into the channel and the pilot instructed the master to heave in the anchor. The attempt to weigh anchor caused the bow of the ship to swing sharply to starboard and the stern to swing back to port. This resulted in the ship grounding again along its port quarter.

The pilot asked the master to walk back the anchor,[11] resulting in the ship’s stern quickly moving clear of the bank and across the channel current such that the current was pushing on the port quarter. The pilot then asked the master to heave in the anchor, which resulted in the ship’s bow again swinging to starboard towards Clara Rock. The pilot ordered the ship’s main engine full astern to gather sternway against the current and thus clear Clara Rock and assist heaving in the anchor.

The bow’s movement continued, and the pilot then ordered the ship’s crew to stop weighing anchor and ordered the tug forward to pull at full power to stop the bow swinging to starboard. The bow was successfully checked. However, because the current was now fully impacting the ship’s port quarter, the stern sheered rapidly to starboard, towards the wharf, and the starboard quarter grounded (Figure 3, bottom left).

Removal to anchorage

The pilot decided to cease any further attempts to retrieve the anchor and instructed the crew to release the bitter end and let the anchor go.[12] The pilot then ordered hard starboard, and full ahead while the 2 aft tugs pulled full to port. The ship came free of the bank on the starboard side of the channel and quickly moved towards Lytton Rocks Reach, clearing Clara Rock (Figure 3, bottom right). As the ship gathered headway, the pilot used the rudder to control the ship’s movement and a short time later instructed the forward tug to lay flat[13] and both aft tugs to stream dead astern.

Once clear of Pelican Banks Reach and into the Fisherman Islands swing basin, the pilot released 2 tugs, retaining one tug on the centre lead aft until clear of the entrance beacons. CSC Friendship was subsequently anchored at the ship-to-ship transfer anchorage at about 0645.

No injuries or pollution resulted from the grounding.

Ship inspections

On 28 February, the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) detained CSC Friendship as unseaworthy pending various investigations, inspections and until necessary repairs had been completed.

Internal and external hull inspections, including an underwater survey, were carried out while the ship was at anchor. The inspections confirmed shell plate damage, including buckling and medium to heavy abrasion of the hull. However, no hull penetration or cracking of plate or welds was found. The propeller had impact damage on 3 of its 4 blades and the rudder was dented and abraded to its lower parts. Although the steering gear was in working order, a rudder angle of only 25° to port could be achieved (designed maximum angle was 35°).

CSC Friendship’s classification society, China Classification Society (CCS), imposed a condition of class on the ship permitting a single voyage to discharge cargo and transit directly to dry dock for repair.

Once AMSA was satisfied with the actions taken and precautions in place, it conditionally released the ship on 4 March. On 9 March, CSC Friendship departed Brisbane bound for Port Botany, New South Wales to discharge cargo and then onto China for repairs in dry dock.

Context

CSC Friendship

CSC Friendship was a Hong Kong-registered, medium range (MR)[14] oil tanker (products) built at the Jinling Shipyard in Nanjing, China, in 2008. The ship was 185 m long with a beam of 32.2 m and had a deadweight capacity of 45,800 t. At the time of the incident, it was loaded with more than 32,000 t of flammable oil products and had a draught of 10.0 m forward and 10.1 m aft. The ship was owned by Fu Ning Marine, managed by Nanjing Tanker Corporation and classed with the China Classification Society (CCS).

CSC Friendship had a crew of 25 Chinese nationals, including the master, all suitably qualified for their positions held on board. The master had joined the ship for the first time as master in April 2021. The working language on board was Mandarin, with English being the language for bridge communications whenever the ship was in port.

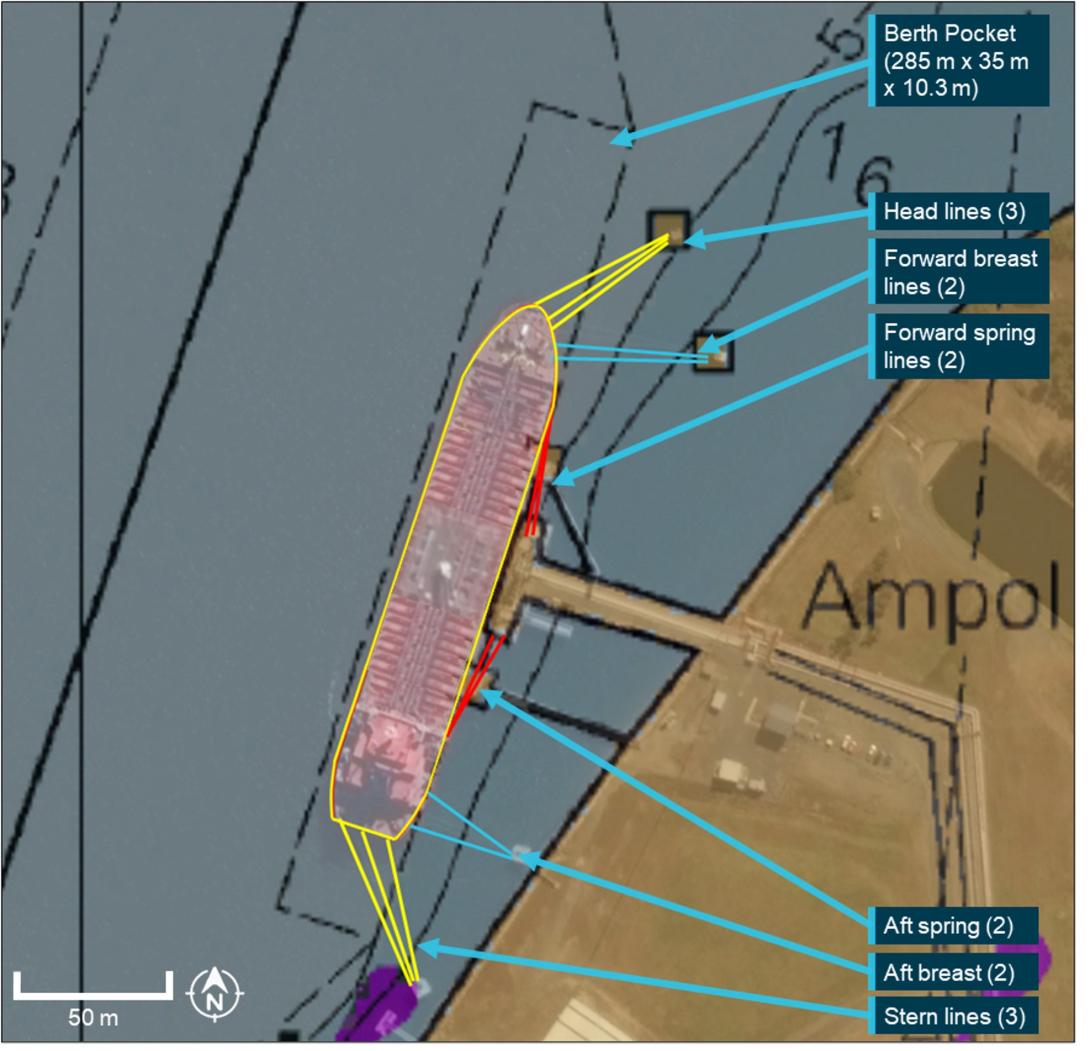

Mooring arrangement

At the time of the breakaway, CSC Friendship was secured with 14 polypropylene mooring ropes – 3 head and stern lines, 2 breast lines forward and aft and 2 spring lines forward and aft, or 3-2-2 forward and aft (Figure 4). Each mooring rope had a minimum breaking load of about 51 t and the ship’s maintenance records indicated they were in good condition. Of the 14 ropes, 12 were run onto drum winches and held by a manual brake set to slip at about 31 t. The ship was therefore optimally secured at the wharf for a tanker of its size, utilising adequate ship and shore mooring equipment to meet industry standards.

Figure 4: CSC Friendship’s mooring arrangements

Source: Australian Hydrographic Office, Google Earth, MSQ, CSC Friendship, annotated by the ATSB

The pilot

The pilot who attended CSC Friendship after its breakaway was a very experienced ship-handler. The pilot had first obtained a master class 1 qualification in 1997, sailed as master in offshore and survey ships before starting as a pilot in the port of Melbourne in 2002. After more than 19 years in Melbourne, the pilot relocated to Brisbane about 6 months before the incident. They then trained and qualified as a licensed (unrestricted) Brisbane pilot and were involved in preparations for PSP’s provision of pilotage services for Brisbane from 2022.

Port of Brisbane

The Port of Brisbane is located at the mouth of the Brisbane River and is Queensland's largest general cargo port with 30 berths. Port throughput in 2021/22 exceeded 32 million tonnes. Imports included:

- crude and refined oil products

- fertilisers

- chemicals

- motor vehicles

- cement clinker and gypsum

- paper and building products

- machinery.

Exports included:

- coal

- refined petroleum products

- grain and woodchips

- mineral sand

- scrap metal

- tallow

- live cattle

- beef and dairy products

- timber.

The Brisbane port limits encompass a significant area of Moreton Bay and extend to the northern end of the bay with about 45 miles[15] from the pilot boarding ground to river entrance beacons. The Brisbane regional harbour master’s (RHM) area of responsibility extends beyond the port limits to include areas of other commercial and recreational activities, including Moreton Bay, the Brisbane River upstream of the port and the coastal sea area to about 45 miles further north of the port limits.

The port was privatised in 2010 and, under a 99-year lease from the Queensland Government, is managed and developed by the Port of Brisbane (PBPL).[16] Collectively, the RHM and the PBPL have responsibility for managing the safe and efficient operation of the port.

While very dependent upon the circumstances at the time, such as number and type of ships in the river and the location of their berths, advice from MSQ and the pilotage provider was that the river, upstream of Pelican Banks, could be safely evacuated of shipping in 6 to 12 hours.

Ampol Lytton Products Wharf

The Ampol refinery is one of 2 oil refineries in Australia. The refinery commenced operations in 1965 and, at the time of the incident, processed in excess of 13,000 tonnes of crude oil each day into refined products such as automotive fuel, diesel and jet fuel. These refined products were vital for fuel supplies to multiple markets in Queensland and across Australia and interruptions to the supply chain could adversely affect communities countrywide. The refinery site included Brisbane River access via the Ampol Lytton Products Wharf (Ampol products wharf).

The Ampol products wharf is located in the narrowest part of the Brisbane River, 6.6 miles upstream of the river entrance beacons, adjacent to the Lytton Refinery. It was wholly owned and operated by Ampol Lytton Refineries (Qld). Maritime Safety Queensland (MSQ), through the RHM, had jurisdiction over all shipping within the Port of Brisbane pilotage area, including arrivals and departures at the Ampol products wharf.

The Ampol Lytton Refinery safety management system included several emergency response procedures related to operations at the Ampol products wharf. The plans and procedures outlined facility preparation and response to emergencies, internal and external, which could affect the facility and its operations. This included the outline of the emergency management organisation, incident scenarios and emergency response. The procedures considered risks at the Ampol products wharf, including fire and oil spill, but did not detail ship related plans or actions. In the case of natural external risk events the incident management team was to assess the risk to shipping and wharves as required. River current or wharf or mooring loads were not considered.

Ampol had completed several studies, reports and assessments of the wharf and berth when assessing its condition, operating parameters and for redesign or upgrade. The studies assessed mooring loads based upon river water speed to a maximum of 2.5 knots as prescribed by the RHM.[17] These studies resulted in guidance and plans for berth capacity, operational limits including surge and passing ships and optimal mooring arrangements.

In addition to the berth mooring arrangements, the industry standard OCIMF[18] mooring equipment guidelines required that shipboard mooring capabilities withstand 3 knots of current from ahead or astern in combination with winds up to 60 knots from any direction.

Part of the Ampol marine specialist’s role was to ensure continued and smooth shipping of product from the refinery and that ships using the berth met or exceeded terminal requirements. Requisites included that the Intertanko[19] chartering questionnaire[20] was completed. This questionnaire required details of mooring arrangements and capabilities, including mooring rope specifications, winch specifications (including brake capacity) and fixed mooring arrangement capacities. CSC Friendship’s master provided Ampol a mooring plan to meet the mooring arrangement requirements for its Brisbane port call.

Brisbane River

The Brisbane River basin drains a catchment of about 13,560 km2 (to the mouth of the river). The river system includes 2 water storage and flood mitigation dams—Somerset Dam on an upstream tributary, which drains to Wivenhoe Dam on the Brisbane River proper. About half of the catchment is above Wivenhoe Dam which is situated about 150 km from the mouth of the river. Seqwater[21] estimates indicated that water released from Wivenhoe Dam would take about 30 hours to reach the port of Brisbane.

The Brisbane River has an extensive documented history of floods, with records dating back to the early exploration of the river by John Oxley in 1824.[22] Flood records for Brisbane City extend back to the 1840s and highlight the range and frequency of flood events that have occurred since official records began.

Seqwater identified Moggill, 72 km from the river mouth (about 14 hours water travel time to the port), as a key location for the assessment of downstream flooding, through Brisbane City and the port. About 93% of the Brisbane River catchment is above Moggill.

The Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) publicly available advice was that, for the lower Brisbane River catchment, downstream of Wivenhoe Dam:[23]

- Major flooding requires a large-scale rainfall situation over the Brisbane River catchment…(and)…average catchment rainfalls in excess of 200-300 mm in 48 hours, may result in…the possibility of moderate to major flooding…throughout the Brisbane River catchment.

- Flooding in the Brisbane City area can also be caused by local creeks…(and) during intense rainfalls, the suburban creeks rise very quickly and can cause significant flooding of streets and houses.

- Average (metropolitan creek) catchment rainfalls in excess of 100 mm in 6-12 hours may result in…major flooding…

2022 flood event

The 2022 rainfall and flooding were the result of a series of slow-moving low-pressure systems that fed a large volume of warm moist air from the Coral and Tasman Seas into eastern Australia. At the time, after 2 years of regularly wet conditions, the rain fell on catchments that were already wet, water storages and river levels were high, and catchments quickly became saturated.[24]

From 21 February BoM forecast heavy rainfall for south-east Queensland, with intense rainfall recorded in areas to the north of Brisbane from 22 February. From the morning of 23 February, flood warnings were issued for rivers in the Brisbane River catchment, upstream of the storage dams. Over the following days, flood warnings were issued for multiple south-east Queensland waterways and at 1635 on 25 February the initial minor flood warning was issued for the lower Brisbane River, at Brisbane City. At this time, there were also major flood warnings for other rivers and creeks higher in the catchment.

Records showed that in the 72 hours to 0900 on 25 February, the average rainfall across the lower Brisbane River catchment was about 110 mm (Table 1). The initial BoM minor flood warning for the lower Brisbane River noted that:

- In the past 24 hours widespread rainfall has occurred across the lower Brisbane River and tributaries, with totals of 70-230 mm observed. Additional areas of heavy rainfall are forecast for the remainder of Friday (25 February) and into Saturday (26 February), which may lead to further rapid river level rises across the lower Brisbane River catchment.

- Minor flooding is likely along the Brisbane River downstream of Wivenhoe Dam.

Table 1 shows average rainfall figures for the lower Brisbane River catchment and related Brisbane River heights (at the city) for the period around the breakaway. The data shows that about 110 mm in 72 hours was sufficient to lead to minor flood conditions. This was followed by significantly more rain in subsequent 24-hour periods (215 mm, 150 mm and 120 mm). This increased volume and rate of accumulated water flowed into the river and through the port.

Table 1: Rainfall and river height for Brisbane River lower catchment

| Date | Time |

Average catchment rainfall in previous 24 hrs (mm) |

River height (m) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 Feb | 0900 |

110[1] |

|

|

| 26 | 0617 |

|

1.7 |

Minor flood level |

| 0900 |

215 |

|

||

| 27 | 0400 |

|

|

Water release from Wivenhoe dam commenced |

| 0514 |

|

2.6 |

Moderate flood level | |

| 0900 |

150 |

|

||

| 2250 |

|

|

CSC Friendship’s breakaway | |

| 28 | 0608 |

|

3.5 |

Major flood level |

| 0900 |

120 |

|

||

| 1000 |

|

|

Approximate time water released from Wivenhoe dam would reach the port | |

| 01 Mar | 0900 |

3 |

|

|

The river level (height) did not reduce to consistently less than the minor flood height until 5 March (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Brisbane River height recorded at Brisbane City, February–March 2022

The height of the tide is referred to the port, and navigational chart, datum: lowest astronomical tide (LAT). When a low water falls below the datum, it is marked with a minus sign (-).

Source: Bureau of Meteorology and Maritime Safety Queensland, annotated by the ATSB

According to BoM,[25] Queensland’s weather is complex and highly dynamic, with weather forecasting carrying inherent uncertainty, particularly at a local scale. The weather event associated with this occurrence was rare and evolved rapidly. Post-event analysis showed that BoM modelling did not initially identify how slowly the weather systems were moving. As a consequence, forecasts, especially further than 24 hours ahead, decreased in accuracy and some places had rainfall in excess of that forecast.

BoM advice changed as the event progressed, however, forecasts and warnings indicated widespread rainfall and flooding was expected across south-east Queensland from 25 February.

Further, BoM reported that more than 50 sites in south-east Queensland and north-east New South Wales recorded more than 1,000 mm of rain in the week ending 1 March 2022. BoM also noted that ‘In recent decades, there has been a trend towards a greater proportion of high‑intensity, short‑duration rainfall events, especially across northern Australia.’

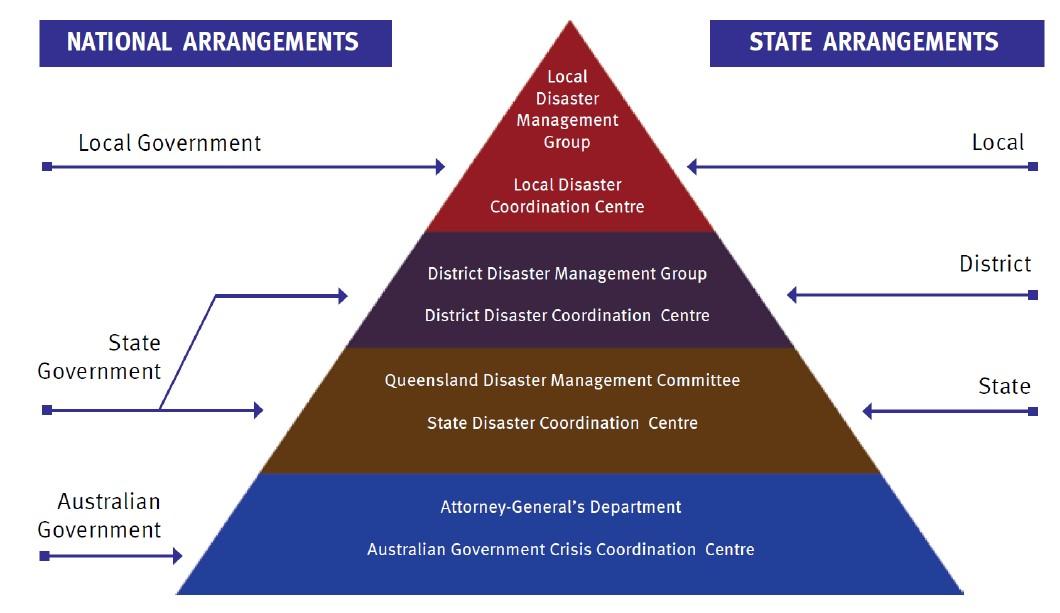

Queensland’s disaster management

Local government is primarily responsible for managing disasters within the local government area with progressive escalation of support and assistance to state/territory government level and beyond as required (Figure 6). The 2022 flood event presented as an event requiring response from both local and state authorities.

At the state level, the framework, arrangements and practices for disaster management in Queensland are established within the Queensland State Disaster Management Plan. The plan includes guidance for disaster management stakeholders through the provision of commentary and directions to supporting documents such as plans, strategies or guidelines. MSQ was represented at the state and district levels and on invitation to the local disaster management group. The Queensland government disaster management arrangements, including risk assessments, training and awareness, guidelines and warnings, are publicly available.[26]

If, during a disaster event, the responding state or territory authority is unable to ‘reasonably cope with the needs of the situation’, there is the opportunity for assistance to be provided by the Commonwealth under the provisions of the Australian Government Disaster Response Plan (COMDISPLAN 2020).[27]

Figure 6: Government disaster management structure

Source: Queensland Government: Queensland State Disaster Management Plan

Maritime Safety Queensland

Marine legislation in Queensland is administered and implemented by Maritime Safety Queensland (MSQ), a state government agency within the Department of Transport and Main Roads. As such, MSQ is responsible for safety oversight of pilotage, pollution protection services, vessel traffic services (VTS) and the administration of all aspects of ship registration and marine safety in the state of Queensland, including the management of an emergency in the port of Brisbane. The agency’s core focus is the preservation of life and property in the state’s waters and in the prevention of, and response to, ship-sourced pollution and other maritime emergencies and disasters. This includes the development of hazard‑specific plans.

Queensland’s 5 maritime regions are each controlled by an RHM.[28] The Brisbane RHM was responsible for the region extending from the New South Wales border (about 60 miles south of the Brisbane River entrance) to Double Island Point (45 miles north of Brisbane port limits). The region included a significant proportion of Moreton Bay and its connected river systems. The RHM was responsible for:

- improving maritime safety for shipping and small craft through regulation and education

- minimising ship sourced waste and providing response to marine pollution

- providing essential maritime services such as pilotage, vessel traffic services and aids to navigation and

- encouraging and supporting innovation in the maritime industry.

Procedures

MSQ provided and maintained procedures applicable to shipping and port operations throughout Queensland with specific procedures for each pilotage or port area.

Port Procedures and Information for Shipping Manual

Each Queensland port had a publicly available Port Procedures and Information for Shipping Manual (PPM) document, which defined the standard procedures to be followed in the port’s pilotage area. The PPM contained information and guidelines to assist the masters, owners, and agents of ships arriving in the port and traversing the area, including details of the services and the regulations and procedures to be observed.

The Port of Brisbane PPM identified the Ampol products wharf (berth) as an area of concern for ship operations such as berth surge and interaction, ship speed limits and specific berthing and unberthing requirements. In particular, the PPM stated that ‘berthing and unberthing of ships at Ampol Products wharf in a “head down” direction is not permitted during the ebb tidal stream.’

Extreme Weather Event Contingency Plan Brisbane—2021/2022

The Queensland Government had published an Extreme Weather Event Contingency Plan (EWE) for each maritime region. Each plan detailed the response required from ship masters and owners to different warning and/or alert levels in that region.

The Brisbane EWE was intended to address the range of adverse weather events that may affect the region, such as summer storms, river flooding or the effects of a cyclone. It was the responsibility of ship owners and masters to take the necessary action within the context of the official weather warnings to protect their passengers, crew and ships, and comply with any directions from the RHM. This included the requirement for all ships to have a safety plan.

The EWE noted that, at times, it may be necessary for the RHM to give directions in relation to the operation and movement of ships when entering, leaving or operating in the pilotage area. This included the evacuation of commercial ships to sea and closure of the pilotage area to all marine activities and operations.

The plan outlined an incremental response encompassing prevention, preparedness, response and recovery phases. The plan aimed to allow appropriate actions in response to the imminent threat to be planned and implemented. Under the EWE, the primary objective was to have the port area secure and safety plans enacted at least 6 hours before the weather event occurred.

Vessel traffic service extreme weather event procedure

An internal vessel traffic services extreme weather event procedure provided information to vessel traffic service operators about extreme weather events in the Brisbane region and the responses required. The procedure provided the trigger points for escalation of response based on the information (warning or other event advice) received.

The procedure stated that, in general, extreme weather in Queensland is cyclone‑related and provided response guidelines for wind, storm, surf and cyclone hazards. The procedure then went on to outline response actions to extreme weather specifically related to the Brisbane River. The river-related events included notification of dam releases and the receipt of BoM flood warnings.

General flood warning response actions included monitoring flood effects on tidal flows, debris in the river and weather warnings. Port users were to be kept informed of the situation through appropriate means of communication.[29] Individual, high‑risk commercial ships and facilities could also receive specific advice and instructions through direct messaging from the RHM. Other, relevant, flood-related precautions contained in the procedure are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Selected VTS extreme weather event procedure flood warning related actions

| Trigger event | Response |

| Minor flood warning |

|

| Moderate flood warning |

In addition to minor flood warning actions:

|

| Major flood warning |

In addition to moderate flood warning actions:

|

| Note: The table does not show all actions contained in the procedure. | |

The procedure advised that the pilotage area would not be re-opened until the RHM was satisfied that all danger had passed, and the pilotage area was safe for ships to re-enter or exit. VTS would then coordinate the safe movement of ships following re-opening.

Severe weather website

Advice for severe weather was also publicly available via the MSQ website.[30] Among other information, this site provided links to the state and regional extreme weather event contingency plans.

Risk and emergency management arrangements

The Brisbane PPM made multiple references to risk assessments to be carried out by port users as well as the RHM, especially in situations outside normal operations, such as for high risk or first‑time ship visits or movements. However, MSQ had no structured, formalised or documented risk and emergency management processes or procedures to ensure that these risk analyses and emergency management steps were taken. The procedures in place for the Brisbane port and VTS then presented as the only tools available for MSQ staff to mitigate the risks associated with port operations.

During this investigation, MSQ stated that risk assessments were conducted (dynamically) during incidents by management and response teams, and were also considered as part of the procedure development process. Any risk assessments conducted during this event were not documented.

To fulfil the role of advising on the prevention of, preparedness for, and response to maritime emergencies and disasters, MSQ was an active member of the disaster management arrangements from local to national levels. MSQ was represented at the state and district levels and on invitation to the local disaster management group.

As the 2022 weather event intensified, MSQ received warnings from BoM, PBPL and other weather stations and public media and through the state disaster management arrangements. VTS and the RHM monitored the situation and river conditions. By the morning of 25 February, the RHM had established contact with other emergency response agencies, including within MSQ’s parent state government department and the state and local government disaster coordination agencies.

Elsewhere, local and state disaster management plans were activated and, by 26 February, the Brisbane Local and District Disaster Management Groups were escalated to ‘stand up’ status.[31] Subsequently, MSQ officers, including the RHM, attended daily meetings of the Local Disaster Management Group.

Starting from 0830 on 26 February, the RHM began issuing situation reports to MSQ management advising of the status of the rain event and its effects on the port and operations. At about this time, an MSQ management team, comprising the Duty Area Manager, the RHM and the MVTS, was convened to discuss the situation. Throughout this period, VTS maintained contact with port stakeholders through radio, telephone, email and messaging services.

Later that day, after the request from the Ampol marine specialist for CSC Friendship to depart the wharf on the evening tide, the RHM consulted the PSP pilot manager about that possibility. As noted earlier (see the section titled Occurrence), the pilot manager advised that a safe, normal departure was not possible in the prevailing conditions.

Vessel traffic service

The Brisbane vessel traffic service (VTS) is the principal resource available to the RHM to manage the safe and efficient movement of ship traffic in the Brisbane VTS area. The VTS operates 24 hours per day, 7 days per week within the declared Brisbane VTS area, which includes the compulsory pilotage area and area within port limits. Standard operating procedures have been established for the VTS.

In addition to normal port operational tasks, during the weather event and river flood, VTS was also tasked with being the initial point of contact for reports regarding debris or other incidents occurring in the river, including calls from members of the public. As a consequence of this flood event, MSQ recovered more than 6,700 tonnes of debris from the Brisbane River.

Weather monitoring

The principal source of weather forecasts, warnings and information for MSQ (via a subscription service) was the BoM. Brisbane VTS received forecasts and warnings from BoM for weather, storm, rain, wind and flood conditions. The information received was passed on to port users by VTS via VHF channel 67 and other means such as email and phone messaging, as required.

MSQ also gathered weather data from a network of 6 tide gauges and 12 weather stations located in the port and surrounding areas. Of these sources, a meter which measured current flow and direction was situated at the 2F beacon in Pelican Banks Reach, about 8 cables[32] (nearly 1.5 km) downstream of the Ampol products wharf and just upstream of where the river opens out into the Fisherman Islands swing basin.[33] The current speed from this meter was prominently displayed on an electronic display board in the VTS centre.

Brisbane VTS also routinely received weather reports from several sources including Seqwater and PBPL NCOS (Nonlinear Channel Optimisation Simulator system).[34] The NCOS system provided wind forecasts and automated warnings to VTS for the port and surrounding Moreton Bay areas.

Advice from Seqwater regarding water releases (forecast and actual) from Wivenhoe Dam was also received by VTS.

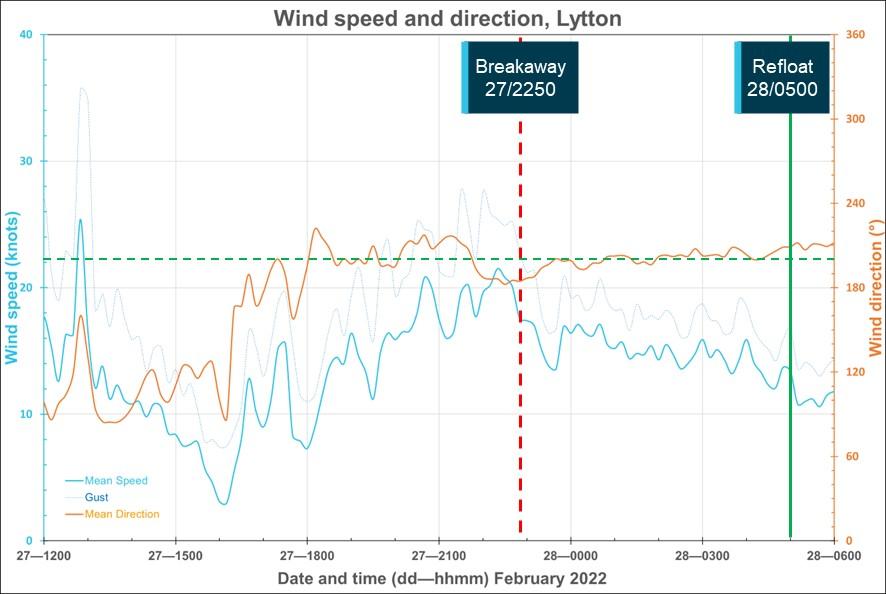

Wind

Throughout the weather event, in addition to storms and flooding, south-east Queensland also experienced significant winds. MSQ received multiple wind and gale alerts and warnings from BoM, the NCOS alert system and from MSQ weather stations. Severe weather alerts issued by BoM from 23 to 28 February included warnings of ‘damaging wind gusts in excess of 90 km/hr (48 knots)’ being possible over south-east Queensland.

The MSQ 2F beacon weather station recorded wind speed and direction in addition to current information. Data from this station showed that for several hours before the breakaway, the mean wind speed was less than 22 knots with gusts less than 28 knots (Figure 7). During this period the direction of the wind aligned with the direction of the wharf. During the following hours and the refloat and recovery task, the wind abated to 10 knots or less.

Figure 7: Wind speed and direction recorded at Lytton

Data recorded at the 2F beacon weather station, about 8 cables downstream from the Ampol products berth.

The Ampol products berth alignment is along the directions 17°-197° indicated by the dashed green horizontal line in the figure.

Source: Maritime Safety Queensland, annotated by the ATSB

Bureau of Meteorology

The Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) is Australia's national weather, climate and water agency, and provides weather forecasts, warnings and observations for coastal waters areas and high seas around Australia.

Among other services, BoM conducts research, consultancy and training in partnership with government and private agencies, industries and organisations. BoM provides tailored products and services to enhance operational decision-making and strategic planning for clients. During the course of the investigation, BoM advised the ATSB that the Brisbane River had exceeded minor flood level 6 times since the 1974 floods.[35]

BoM is the lead national agency with responsibility for flood forecasting and warning and is tasked to issue ‘warnings of…weather conditions likely to give rise to floods...’.[36] BoM issued over 500 warnings across the duration of this weather event (to 7 March), including 27 severe weather warnings from 22 February until the breakaway. It was the principal source of weather information for MSQ.

After this incident, BoM stated that,[37] in hindsight, the official rainfall and flood forecasts for this event performed well given the inherent uncertainties.

Pilotage

All ships over 50 m in length calling at Brisbane are required to take a pilot. From 1 January 2022, Poseidon Sea Pilots (PSP) provided the port’s pilotage services under contract to MSQ.

Safety management system

Before PSP was awarded the contract, it submitted a comprehensive documented safety management system for the port’s pilotage operations. Titled ‘Pilotage Operations Safety Management System (POSMS)’, it was based upon and intended to complement the port procedures manual (PPM) and in the event of inconsistency, the PPM was to take precedence. The POSMS was reviewed and endorsed by MSQ and was subject to an annual audit schedule. The PPM contained requirements and guidance for pilotage in Brisbane, including navigation and operational restrictions such as specific limitations for the Ampol products wharf.

The POSMS provided treatment of risk management principles and processes as well as guidance on pilotage emergencies and the management of such. This included PSP-specific emergency management guidance in addition to information derived from the PPM. The procedures included details of PSP’s emergency management structure, roles and responsibilities and lines of communications.

An emergency was defined as ‘a situation that has developed during an act of pilotage’ that could lead to damage, harm or injury. As such, preparations for and response to a developing emergency caused by wider port or external influences, such as a river flood creating dangerous conditions for ships berthed in river/port, did not trigger the PSP emergency management procedures. Port emergencies were to be managed by the RHM with PSP support if required.

The PSP emergency and risk management arrangements were directed at addressing issues with the operational piloting aspect of the service. The arrangements did not include a formal process or structure to address and document the management of wider port and regional safety to which the pilotage service provider is an important and major contributor. The provider had no direct role in disaster and emergency management, including the Extreme Weather Event Contingency Plan, described earlier (see the section titled Maritime Safety Queensland, Procedures), other than supporting decisions taken by MSQ and following the RHM’s directions to manage port/shipping emergencies.

The POSMS allowed for deviations from procedures as long as the safety of the operation was not compromised. The action was to be discussed with PSP management and the RHM and supported by a risk assessment. Operational guidance was provided for conditions including guidelines for wind including force calculations for wind speed versus exposed area. However, hazardous conditions associated with river flood or high current speed were not addressed.

Operations

In the months prior to commencement of pilotage services, all PSP pilots completed multiple observation trips into and out of the Port of Brisbane, conducted ship simulator training and were assessed by an MSQ check pilot prior to being licensed by MSQ. Simulation training included emergency training, but this did not include manoeuvring or piloting in river flood conditions such as experienced during this incident. PSP procedures, similarly, did not include guidance for pilotage in such conditions. Further, PSP procedures did not include plans or arrangements for evacuation of the port.

In general, PSP management liaised directly with the RHM or delegate to co-ordinate and plan pilotage within the port. The PSP offices were adjacent to the Brisbane River and personal observation of the river and conditions, in addition to information available from VTS, formed part of pilot knowledge and assessment of operations.

During this event, PSP management assessments of river conditions were that pilotage and ship manoeuvring would be affected from 24 February and operations in the river were unlikely from the afternoon of 25 February due to excessive ebb flow.[38] It reported raising these matters with the RHM but no records exist to verify specific matters although it is evident that there were several communications between PSP and MSQ (RHM or VTS).

On 26 February, PSP was contacted by VTS to follow up the request for CSC Friendship departing the Ampol products wharf to sea. The PSP pilot manager, in consultation with another experienced pilot, conducted a risk assessment of the manoeuvre. The assessment was informal and not recorded. They concluded that, given the proximity of Clara Rock (about 300 m downstream of the ship) and the river conditions (high ebb flow and significant debris), the risk was unacceptably high, even with additional tugs.

As the weather event intensified, PSP operations were affected, including the provision of pilots to ships from the pilot station at the north of the port limits (Mooloolaba for Point Cartwright) due to flooded roadways. This resulted in 2 pilots locating to Mooloolaba and another on standby from Brisbane.

In submission to the draft of this report, PSP stated that the risk assessment following the request to consider departing CSC Friendship from the wharf was largely based on the standard PPM requirement prohibiting movements at that berth during an ebb flow. It further stated that moving the ship in those conditions could only have been undertaken under formal direction by the RHM to conduct the pilotage outside PPM-imposed limits.

Towage

Harbour towage requirements were specified in the Port Procedures and Information for Shipping Manual (PPM). The tug base was located in Boat Passage adjacent to Pelican Banks and about 5 cables downstream of the Ampol products wharf.

Five tugs were normally available for booking and allocation. During the weather event, from 26 February, 2 tugs were kept on active standby with a third on short notice. The flooding and resulting road closures restricted the movement of tug crews and resulted in the 3 tug crews being restricted to the tug base and on board the tugs. This, coupled with the dangers posed by the debris in the river, limited the number and availability of tugs to assist operations within the port.

The effectiveness of the tugs at the time of the breakaway and subsequent groundings of CSC Friendship was observed to be significantly reduced when operating in the excessive current.

Safety analysis

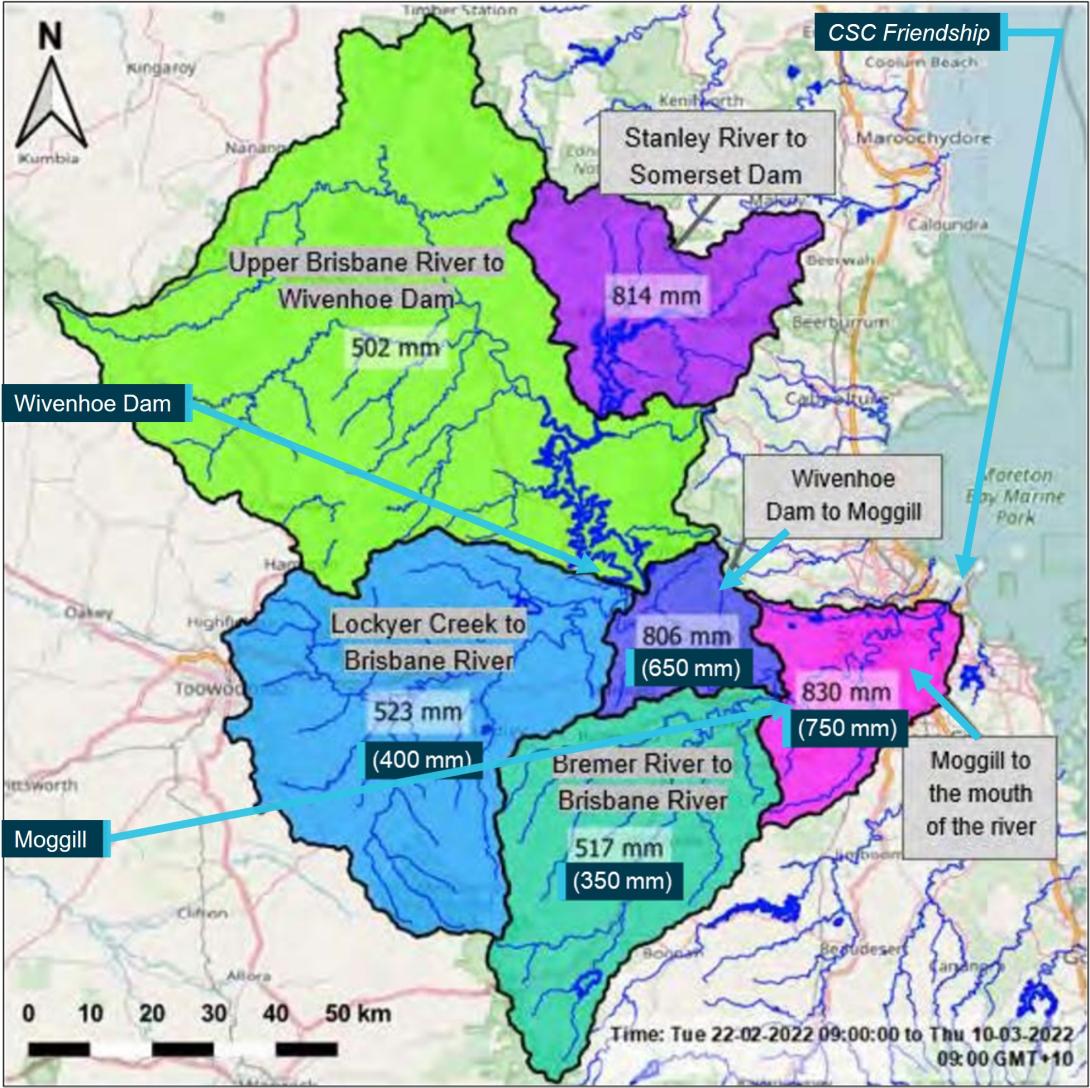

Introduction

From 22 February 2022, south-eastern Queensland experienced a multi-day rainfall and flooding event during which multiple sites recorded in excess of one meter of rainfall. In the 5 days prior to the breakaway of CSC Friendship, more than 500 mm (average) rain fell over the entire Brisbane River catchment (Figure 8). This led to significant inflow into the Brisbane River, resulting in major flooding and increased water speed (peaking at about 5 knots) through the Port of Brisbane.

While additional water release from Wivenhoe Dam had commenced at 0400 on 27 February, travel time for this water meant that it would not impact the port for at least 24 hours (that is, several hours after the breakaway).

Figure 8: Average rainfall depths for the Brisbane River sub-catchments from 22 February to 10 March 2022

The figure shows average rainfall depths for the sub-catchments which constitute the Brisbane River basin. Bracketed figures are average rainfall depths for the 5-day period, 22 to 27 February, and cover the lower Brisbane River catchment (below Wivenhoe Dam).

Source: Seqwater with annotations by the ATSB.

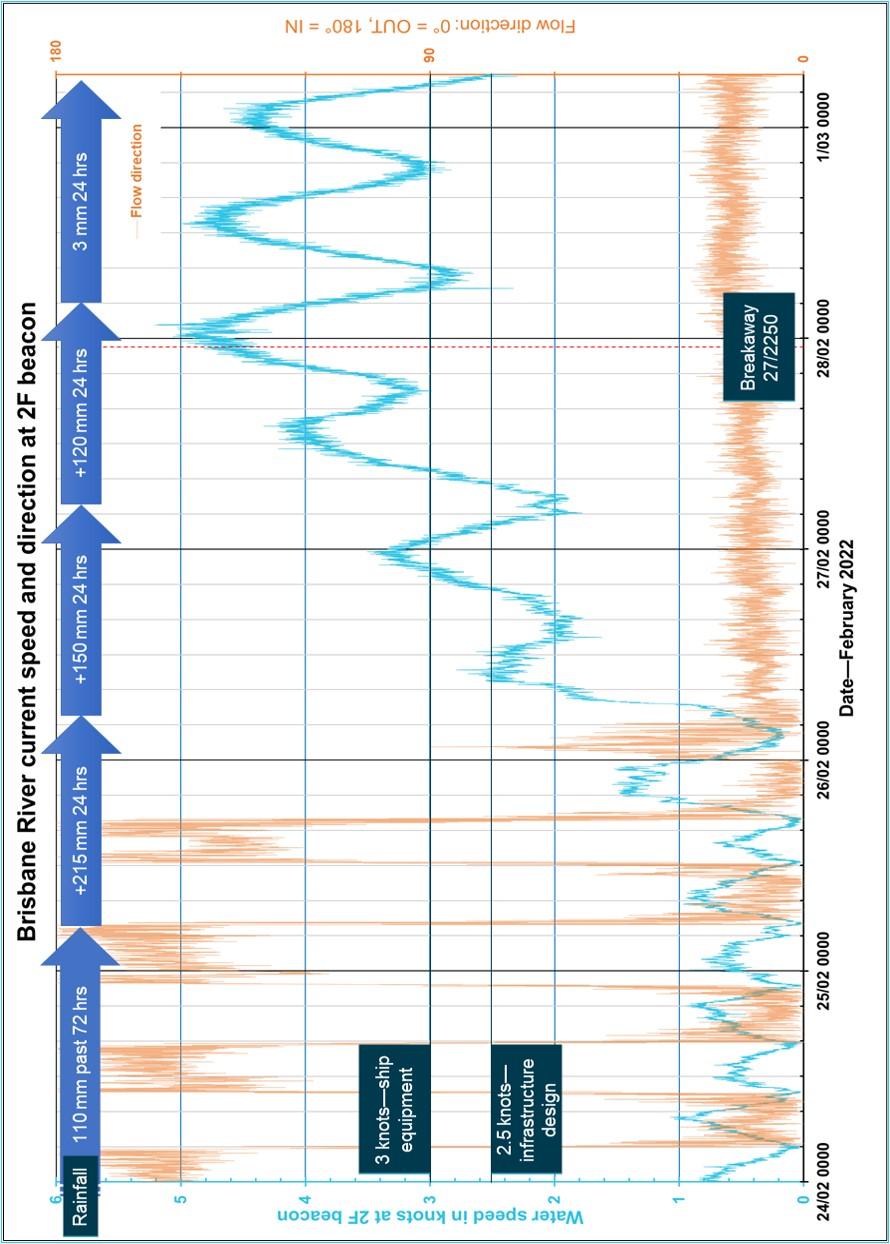

The breakaway

Recorded current data showed that the mooring arrangements and equipment (both ship and berth) withstood current speeds in excess of design requirements on multiple occasions prior to the breakaway (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Brisbane River current speed and flow direction

Date label shows the start of that day (0000 hrs) local time

Rainfall arrows show average rainfall across the lower Brisbane River catchment to 0900.

Source: Maritime Safety Queensland annotated by the ATSB

The mooring equipment and its arrangement to secure ships at the Ampol Lytton Products Wharf were designed to withstand current speed of at least 2.5 knots. Additionally, CSC Friendship’s mooring equipment was required to withstand 3 knots of current from ahead or astern. At the time that the ship surged ahead, the current was recorded at more than 4.5 knots from astern and had been more than 3 knots for the preceding 14 hours.

The forces imparted by the increasing water speed exceeded the capabilities of the ship’s mooring arrangement and equipment leading to its mooring winch brakes slipping, lines parting and the ship breaking away. During attempts to return the ship to the wharf using tugs and operating astern propulsion on its main engine, the ship’s stern swung to port. This exposed the ship’s quarter to the current, increasing the hull surface exposed to it and the ship broke away from the wharf. The current then pushed the ship across the channel (to its northern side) where it grounded, 400 m downstream of the wharf.

After initial attempts to refloat the ship, it remained aground while inspections and refloating and removal plans were made. The ship’s port anchor had been deployed with 6 shackles of chain out (about 170 m), and it was decided to retrieve the anchor and move the ship downriver and out of the port. At 0500 on 28 February, with the assistance of tugs, as the ship was refloated and the anchor heaved in, the ship veered across the channel toward Clara Rock. The ship was kept clear of Clara Rock but its stern touched bottom.

At this stage further attempts to retrieve the anchor were abandoned and the anchor cable was let go at the bitter end. The ship was then manoeuvred clear of Clara Rock and back into the channel using tugs and the main engine.

After the master’s repeated requests, the pilot agreed to attempt to retrieve the anchor. However, as the anchor was heaved in, control of the ship was lost, it veered across the channel and grounded in close proximity to Clara Rock. Pilot testimony after the incident was that, once clear of Clara Rock, control of the ship and manoeuvring in the channel were better than anticipated in the strong following current. With hindsight, this suggests that slipping the anchor and subsequent removal of the ship directly to sea from the initial grounding location probably would have involved lower risk than attempting to retrieve the anchor.

Incident preparedness

It is acknowledged that this weather event was very unusual and extremely rare (estimated recurrence interval between 300 and 800 years);[39] notwithstanding, appropriate planning and preparation for emergencies, including rare events, is important. This importance was reiterated in a Queensland Government report about this event, which stated:

This (weather event) demonstrates the importance of response agencies and the community adopting a high risk threshold and taking a conservative approach to planning and preparation (that is, plan for the worst-case scenario and hope for the best-case scenario) to ensure preparatory actions are taken for extreme weather events.[40]

The ATSB found that the following data and information were available, prior to the breakaway, to assist Maritime Safety Queensland (MSQ) with weather‑related decision making:

- BoM weather monitoring, forecasting and warnings regarding the weather system approaching south-east Queensland, including:

- an initial flood watch issued on 22 February for possible minor to major flooding in catchments, including the upper and lower Brisbane River

- a minor flood warning issued on 23 February for rivers upstream of Somerset and Wivenhoe dams

- further progressive flood warnings from 25 February for both the upper and lower Brisbane River

- advice, including multiple severe weather warnings, that the weather system was likely to produce areas of heavy to intense rainfall and thunderstorms over south-east Queensland and, as catchments were already wet, there would probably be significant runoff.

- rain and river observations and reports, including local and state authorities and public news broadcasts from 24 February, noted that river current was increasing, with debris in the river.

- river current recorded at the 2F beacon and displayed in the VTS centre:

- shows it was effectively in persistent ebb from about 1700 on 25 February (Figure 9)

- exceeded 2.5 knots from 0730 on 27 February

- exceeded 3 knots from 0900 on 27 February.

- operational guidelines and limits for ships and infrastructure within the port, including that:

- MSQ RHM guiding river current speed for assessment and design of safe berthing infrastructure and mooring arrangements was 2.5 knots

- oil tanker mooring design requirements were to meet established guidelines and withstand water speed of 3 knots (in combination with wind speeds to 60 knots)

- the port procedures manual stated that there were to be no shipping movements from the Ampol products wharf in an ebb flow.

In summary, the weather information identified that a large-scale weather event was affecting south‑east Queensland, resulting in a significant volume of water in the Brisbane River catchment. The weather event was a rare occurrence and evolved rapidly resulting in BoM forecasts and advice changing many times in response to the dynamic and challenging conditions. However, by 25 February (about 2 days before the breakaway), it was clear that conditions would continue to deteriorate over the following days. Significantly, all this anticipated water would flow to the sea through the port, increasing the risk that the current flow would exceed infrastructure and mooring limits.

In this context, it was reasonably foreseeable that the risks to ships and infrastructure could escalate to dangerous levels and that the time window to safely remove ships to sea would likely close. However, although port management took steps to further secure berthed ships, the increasing risk to the port of the rain continuing to fall in the catchment was not effectively managed.

In addition, MSQ (and VTS) did not have a structured, formalised or documented emergency management process, and documentation did not include procedures for the management of emergencies or assessing and managing risks. A review of the procedures identified that the assessments of hazards to the port had not considered sources of increased river flow or the risks associated with currents beyond those normally encountered. Consequently, there were:

- no arrangements in place to translate the information being received into succinct, relevant information or messaging in a form that the decision-making team could use for timely and prudent decisions

- no response escalation trigger points linked to current speed or other measures such as river heights, water flow rates or catchment inflows – the 2F beacon current meter provided real‑time information but no forecasting, in part due to its location

- no plans, guides or procedures for ship manoeuvring in conditions exceeding those normally experienced, especially in sustained or high ebb flow

- no readily usable procedures or plans for port evacuation

- no lists of priority berths or ship types to evacuate.

As a result, the information received had to be managed and assessed by the RHM’s team with no documented procedures, operational limits or response and escalation triggers to manage the risks of a breakaway.

Consequently, when the time came to make critical decisions quickly in response to the rapidly deteriorating conditions, it was decided that the risk of moving ships (evacuating the port) outweighed the risk posed by them remaining at their berths in the flooding river. There was no procedure or process to record risk assessments and any that were conducted were not documented. The risk posed by CSC Friendship remaining at its berth was subsequently realised when it broke away and grounded multiple times. The significant risk that the laden tanker then posed had to be managed through its complicated removal from the river in adverse conditions, which itself involved elevated risk.

Poseidon Sea Pilots

Pilots are a valuable resource for consultation and advice to port authorities for ship operations under any conditions within the port. As such, the pilotage service provider is one of the principal risk mitigators for a port and for ship operations. They should therefore be actively involved in preparations for, assessment of, and response to, any situation affecting shipping in the port.

Poseidon Sea Pilots (PSP) commenced operations as the pilotage provider for the port of Brisbane in the months before the incident. In the time leading up to becoming the pilotage provider, PSP engaged with MSQ, the RHM and the port community in ensuring efficient and safe movement of ships, with MSQ consulted in the revision and development of PSP’s POSMS.

Despite only being the provider for a relatively short time, PSP pilots had piloting experience in ports other than Brisbane and underwent several months of prior training and preparation. As an active and knowledgeable contributor to management of port operations, the pilotage provider should have plans and processes in place to prepare for and assist port authorities in the event of an emergency.

The Brisbane River has a long history of flooding and there had also been several significant recent flood events (since 2011). However, while PSP had practised normal operations and ship emergencies such as loss of propulsion or steering, pilots’ experience and training did not include preparing for a persistent high current event as experienced during this incident.

The PSP pilot manager was aware of the unfolding weather event and on 24 February had become concerned with conducting shipping movements in the river due to the speed of the current and the amounts of debris floating down the river. However, at that time the pilot manager considered that shipping movements upstream of Pelican Banks were still possible by exercising caution. Shipping movements downstream of Pelican Banks, to and from berths on Fisherman Islands, remained unaffected.

As the rain intensified and conditions deteriorated, on 25 February, the pilot manager assessed that shipping movements above Pelican Banks were no longer feasible. On 26 February, when specifically contacted by VTS about moving CSC Friendship, the risk assessment, largely based on the standard requirement prohibiting movements at that berth during an ebb flow, concluded that it was safer for the ship to remain alongside.

However, as the rain continued to fall, and the already accumulating surface water flowed to the river and the port, conditions were predictably going to worsen, especially with the days of very heavy rainfall from 25 February onwards. This continued deterioration of conditions and increase in risk should have been evident to PSP management and highlighted to the RHM.

Preparations for, and response to, the situation were not supported and guided as PSP did not have in place a structured process, documentation or procedures for:

- assessing and conducting operations outside normal operating conditions, or conditions limited by the port procedures manual

- operational planning for ship handling, manoeuvring or prioritising in circumstances such as port evacuation, conducting shipping movements in persistent and/or high ebb flow or removal of ships to sea for safety purposes

- formalised arrangements, procedures or agreements with the port authority (MSQ) to collaboratively assess and respond to adverse conditions affecting port operations and ship movements

- observing and assessing wider port and district conditions which may affect port operations including prediction of deteriorating conditions.

As a consequence, there was no pre-planning or preparation for the unfolding events and risks threatening the safety of berthed ships. It was only after the emergency communication from VTS following the breakaway that PSP had an active role, which essentially was a recovery operation that could have been avoided or mitigated through planning and preparation with MSQ.

According to PSP, it met its obligations by complying with its POSMS that covered normal pilotage operations, and the overarching PPM and RHM directions in an MSQ-managed emergency. This was the basis of PSP’s risk assessment to move CSC Friendship in conditions well outside the PPM‑imposed limits when, it stated, formal direction by the RHM was required to consider the risks of the movement outside the normal limits (see the previous section titled Pilotage, Operations).

However, if PSP expected or required the RHM’s formal direction, it should have explicitly raised that at the time. Further, a proactive approach by PSP to discuss all considerations and risks in relation to the worsening situation in the port would have been far more effective in preparing for and managing the situation. This is particularly important as an emergency involving a ship in the port will almost certainly involve PSP and its pilots and it was, therefore, essential that its POSMS addressed these matters.

Ampol’s operations

Ampol employed a marine specialist to ensure the safe and efficient turnaround of ships at the products wharf to maintain the supply of petroleum products to customers from one of just 2 oil refineries in Australia. When made aware of the possibility of port closure, the marine specialist attempted to expedite CSC Friendship’s departure to maintain the movement of products in the supply chain. The trigger for the decision was the avoidance of commercial disruption rather than safety concerns. Ampol’s request to allow the ship to depart was made with the reasonable expectation that MSQ and PSP would have risk assessed its request in the context of possible port closure and available safe options.

Ampol’s procedures, risk assessments and guidance for operations at the products wharf did not include risks to associated infrastructure and ships berthed there due to river conditions, including current. While aware of the weather event and deteriorating conditions, the marine specialist did not have access to river current data. Consequently, neither Ampol nor the ship’s master were alerted when the river current exceeded the design capabilities of both ship and shore mooring equipment and arrangements.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. Safety issues are highlighted in bold to emphasise their importance. A safety issue is a safety factor that (a) can reasonably be regarded as having the potential to adversely affect the safety of future operations, and (b) is a characteristic of an organisation or a system, rather than a characteristic of a specific individual, or characteristic of an operating environment at a specific point in time. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the breakaway and grounding of CSC Friendship, Port of Brisbane, Queensland on 27 February 2022.

Contributing factors

- From 21 February 2022, the Bureau of Meteorology issued forecasts and warnings for heavy, sustained rainfall over south-east Queensland, including the Brisbane River catchment. This rainfall led to several days of continuous, high, ebb current speeds through the Port of Brisbane, which exceeded the design parameters of wharf and mooring arrangements at the Ampol products berth.

- CSC Friendship remained at the Ampol products berth in deteriorating conditions which exceeded ship design mooring limits.

- Increasing river flow generated forces that exceeded the capabilities of CSC Friendship’s mooring arrangement. The ship surged downstream, parted mooring lines and broke away. Despite the best efforts of ship’s crew and assisting tugs and others, the ship came off the wharf, was swept across the channel and grounded on the northern side of the river, about 400 m downstream of its original berthed location.

- During refloating and removal of the ship from the river, manoeuvring of the ship when attempting to recover its anchor led to it grounding on the southern side of the river, in close proximity to Clara Rock.

- Maritime Safety Queensland (MSQ) did not have structured or formalised risk or emergency management processes or procedures. Consequently, MSQ was unable to adequately assess and respond to the risks posed by the river conditions and current exceeding operating limits and ensure the safety of berthed ships, port infrastructure or the environment, and avoid CSC Friendship’s breakaway. (Safety Issue)

- Poseidon Sea Pilots’ (PSP) safety management system for pilotage operations did not have procedures or processes to manage predictable risks associated with increased river flow or pilotage operations outside normal conditions. This, in part, resulted in PSP not considering risks due to the increased river flow properly and not taking an active role until after the breakaway. (Safety Issue)

- Ampol’s assessment of risk to the ship and facility did not consider water speed in excess of the design and safety limits for the ship and berth mooring arrangements. (Safety Issue)

Safety issues and actions

|

Central to the ATSB’s investigation of transport safety matters is the early identification of safety issues. The ATSB expects relevant organisations will address all safety issues an investigation identifies. Depending on the level of risk of a safety issue, the extent of corrective action taken by the relevant organisation(s), or the desirability of directing a broad safety message to the marine industry, the ATSB may issue a formal safety recommendation or safety advisory notice as part of the final report. All of the directly involved parties were provided with a draft report and invited to provide submissions. As part of that process, each organisation was asked to communicate what safety actions, if any, they had carried out or were planning to carry out in relation to each safety issue relevant to their organisation. Descriptions of each safety issue, and any associated safety recommendations, are detailed below. Click the link to read the full safety issue description, including the issue status and any safety action/s taken. Safety issues and actions are updated on this website when safety issue owners provide further information concerning the implementation of safety action. |

Maritime Safety Queensland emergency preparedness

Safety issue number: MO-2022-003-SI-01