What happened

On 10 June 2016, the pilot of an Agusta S.P.A A109S helicopter, registered VH-XPB, prepared to conduct a private flight under the instrument flight rules[1] from Sydney Airport to Ellerston, New South Wales (NSW), with three passengers on board. As the planned arrival time at Ellerston was after dark, the pilot contacted ground personnel at Ellerston before departure, who advised there was lighting at the helicopter landing site (HLS). The pilot also entered the coordinates of the HLS into the helicopter’s global positioning system (GPS). The elevation of the HLS was 1,720 ft above mean sea level (AMSL).

The helicopter departed Sydney at about 1738 Eastern Standard Time (EST). During the cruise at 8,000 ft AMSL, the helicopter entered cloud, with the cloud base at about 4,500 ft. When about 10 NM from Ellerston, the pilot commenced a descent to the calculated lowest safe altitude[2] of 6,500 ft.

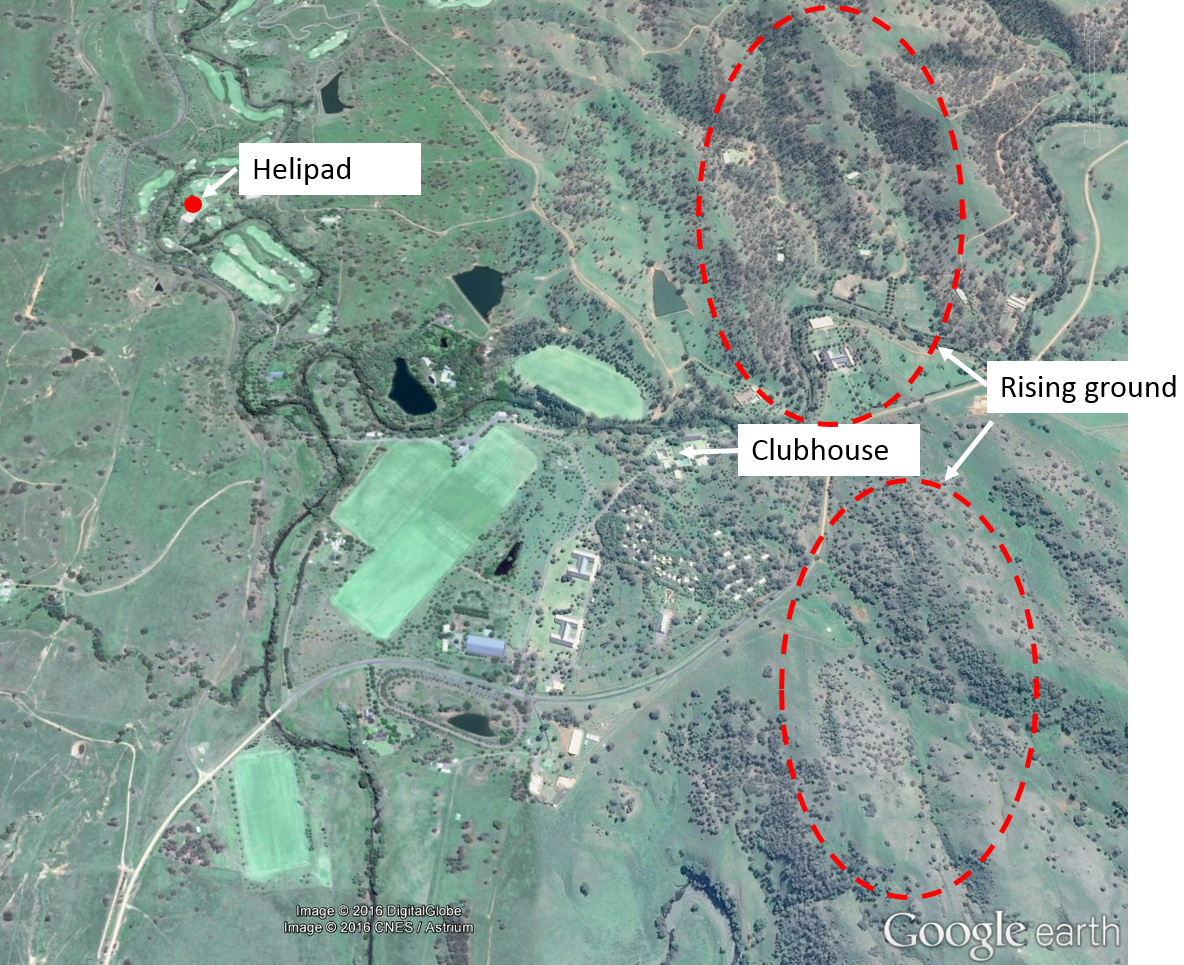

When about 3 NM from Ellerston, with the property in sight, the pilot commenced a descent to 3,500 ft, to ensure adequate terrain clearance for arrival overhead the GPS position of the helipad (Figure 1). During the descent, the pilot sighted the lights from the buildings at Ellerston and visually confirmed they were at the intended location.

Figure 1: Ellerston property

Source: Google earth – annotated by ATSB

At about 1838, the helicopter arrived overhead the GPS position for the helipad. The pilot sighted a red beacon, but as they had expected to see the illuminated hangar and helipad, became unsure of the location of the HLS. The pilot reported that they then descended to about 2,500–3,000 ft and tracked to the west and north-west towards other lit buildings and then to the east back over the red light, but did not see any illumination indicative of a HLS. The pilot then elected to track towards the buildings of the homestead and descend to verify their exact location.

At about 1841, the helicopter descended to 2,286 ft (according to recorded data) in the vicinity of the Ellerston clubhouse and nearby buildings which the pilot reported were all well illuminated and visible. The elevation of the terrain at that point was 1,770 ft with rising ground to the north and south-east up to 2,250 ft (Figure 1). The pilot reported that they were then sure of their exact location, and assessed that the red light must be on the hangar next to the HLS.

The pilot then commenced a right turn to position for an approach from 2 NM to the north-east of the HLS. At about 1842, as the aircraft was positioning for the approach, the pilot received a ‘landing gear’ warning from the radio altimeter. This warning is generated whenever the helicopter is below 200 ft above ground level (AGL) without the landing gear extended. The pilot immediately raised full collective and commenced a climb to 4,000 ft AMSL tracking towards the south. A low rotor RPM occurrence was recorded on the aircraft computer at 1842, indicative of a rapid raising of the collective.[3]

After climbing to 4,000 ft, the pilot turned to track towards the red light from the south-south-west, and saw a flashing bright torch light near the red light indicating the HLS. The pilot then positioned the helicopter to the north-east of the HLS and commenced an approach. During the approach, ground personnel shone car headlights from the sealed area, which confirmed to the pilot that the helicopter was approaching the helipad. At about 50 ft AGL, the pilot was able to identify ground features at the helipad and continued with the landing.

After landing, the passengers disembarked and the pilot refuelled the helicopter. The pilot then conducted a ferry flight to Camden Airport, NSW. After arriving in Camden, the helicopter was pushed into a well-lit hangar, at which stage damage to the helicopter was detected. It was apparent that the helicopter had struck a tree branch, causing damage to the right-side landing lights, horizontal stabiliser, vertical fin and rotating beacon (Figure 2). It was unclear exactly when the helicopter had struck a tree.

Figure 2: Damage to right landing light of VH-XPB

Source: Helicopter operator

Pilot comments

After overflying the buildings and positively establishing the helicopter’s position, the pilot turned right to track north. A line of hills ran north-south from that area. The pilot was then attempting to maintain about 500 ft AGL and when the 200 ft radio altimeter ‘landing gear’ warning sounded, the helicopter was either descending (without the pilot realising) or maintaining altitude, but heading towards rising ground.

The pilot assessed that the helicopter probably struck a branch when the 200 ft warning sounded. The pilot did not hear or feel the collision, but at the time the warning sounded, the pilot rapidly raised full collective and their workload was high. If the collision with the tree branch had occurred later during the approach to the helipad, the pilot thought they would have heard or felt it due to lower airspeed and engine power settings. The pilot was not aware of having struck anything and no damage was detected during refuelling at Ellerston.

The pilot had landed at Ellerston three times previously in daylight but had not been there at night. After speaking to ground personnel prior to the flight, the pilot was expecting the sealed area and helipad to be illuminated. When there was no illumination visible from above, in the vicinity of the helipad, the pilot became confused as they could see the red light but not the helipad. In response, they orbited to confirm their position and then to determine where the helipad was in relation to that position. They were then trying to get visual reference with the landing site and remain at a safe height above the terrain and any obstacles.

Due to the overcast cloud, there was no celestial illumination, and as the area was surrounded by high ground, it was a black hole. In that situation, the pilot’s attention was split between looking outside to establish their position relative to the landing area, and inside at the instruments to maintain altitude and speed.

On a dark night, pilots need to apply greater safety margins such as use of the autopilot to reduce pilot workload, and maintaining a greater height above terrain until the landing site has been positively identified and an approach commenced.

Aircraft satellite tracking data

The helicopter was fitted with a satellite tracking system which recorded the time and the helicopter’s position, height and speed, at 2-minute intervals. The 200 ft warning occurred between two of the recorded points, so the exact position and altitude of the helicopter at that time was not recorded.

Operator report

The helicopter operator conducted an investigation and found the following factors contributed to the incident:

- It was assumed by the company that the pilot was familiar with the layout and positioning of the Ellerston village and helipad because they had operated there on multiple occasions during daylight in the same aircraft, and they had discussed lighting arrangements with ground staff prior to the flight.

- The helipad did not have the appropriate edge lighting to identify it as a HLS for night operations.

- After flying overhead and realising the need to orbit to identify the helipad, the pilot should have nominated a vertical limit of 3,500 ft and a horizontal limit of 2 or 3 NM to prevent inadvertent controlled flight into terrain. A descending turn while scanning between ground lights and instruments in a pitch-black environment creates a very high workload. Planning the descent with absolute limits is critical to maintaining situational awareness. The use of autopilot in this situation can also aid in reducing workload while scanning outside.

- Although the pilot was highly experienced and current with regard to regulatory requirements, lack of training in the conduct of ‘black hole’ approaches (recognised as a particularly demanding exercise) was identified as a factor.

Safety action

Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following safety action in response to this occurrence.

Helicopter operator

As a result of this occurrence, the helicopter operator has advised the ATSB that they are taking the following safety actions:

- Introduction of night, black hole approach training and controlled flight into terrain avoidance technique training for all pilots who conduct night and IFR operations. This is to include both inflight and simulator training.

- No company pilot will be authorised to fly into the Ellerston helipad at night without specific familiarisation training from the local pilot.

- It is recommended that the Ellerston HLS be assessed against standard HLS lighting requirements for any future night operations.

- All private helipads with potential for night operations are to be risk assessed and documented procedures produced.

- Adjustment of the radio altimeter warning decision height for the A109 is limited to the standard 200 ft and 150 ft alerts. A variable decision height warning device is to be investigated.

- The company will increase the reporting rate on the satellite-tracking device from 2-minute to 1-minute intervals.

Safety message

The ATSB publication Avoidable Accidents No. 7 - Visual flight at night accidents: What you can't see can still hurt you explains how suitable strategies can significantly reduce the risks of flying visually at night.

The extra risks inherent in visual flight at night are from reduced visual cues, and the increased likelihood of perceptual illusions and consequent risk of spatial disorientation. Situational awareness with respect to the relative position of terrain and obstacles is fundamentally important during the conduct of limited visibility operations.

Aviation Short Investigations Bulletin- Issue 52

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2016

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

- Instrument flight rules permit an aircraft to operate in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC), which have much lower weather minimums than visual flight rules. Procedures and training are significantly more complex as a pilot must demonstrate competency in IMC, while controlling the aircraft solely by reference to instruments. IFR-capable aircraft have greater equipment and maintenance requirements.

- The lowest altitude which will provide safe terrain clearance at a given place.

- A primary helicopter flight control that simultaneously affects the pitch of all blades of a lifting rotor. Collective input is the main control for vertical velocity. Raising or lowering the collective lever increases or decreases the main rotor lift, which increases or decreases main rotor drag. The collective lever is also connected to the engine anticipators, which respond to raising or lowering of the collective by increasing or decreasing engine power to compensate for the changes in main rotor drag and govern the main rotor speed.