Safety summary

What happened

At about 0513 on 12 March 2015, the driver of a Sydney Trains A-set passenger train operated the train in the wrong running direction from Mt Druitt station. Instead of travelling towards St Marys on the Down Suburban line, he drove 761 m in the opposite direction towards Blacktown. The driver only braked after a network control officer (NCO)[1] contacted him and told him to stop. At the time, only the driver and guard were on board.

At the same time, a Pacific National freight train was about four kilometres away and travelling towards the passenger train on the same line. The NCO also called the driver of the freight train and told him to stop. There were no injuries or damage as a result of this incident.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that a number of factors contributed to the driver losing awareness of the way the train was facing. It was likely the driver was:

- confused about the direction due to changing ends seven times

- distracted from the main task of driving as he had spent over 3 hours at Mt Druitt station performing other tasks before he started driving

- at risk of making an error due to his high workload

- feeling under pressure to move the train

- impaired by fatigue due to being awake for over 21 hours and in the low range of the circadian sleep cycle.

Sydney Trains fatigue management processes were ineffective in identifying the fatigue impairment experienced by the driver.

The guard did not take any action to stop the train although the guard was aware that the train was running in the wrong direction.

What's been done as a result

Sydney Trains conducted an internal safety investigation and is implementing several safety actions in response to that internal report.

Safety message

Rail operators should ensure that adequate strategies exist to safeguard against fatigue impairment of train crew. It should also be noted that train crew have a responsibility to decline a shift if they feel that their performance may be affected by fatigue.

SydneyTrains A-set

Source: OTSI

__________

Events prior to the occurrence

On Wednesday 11 March 2015, at about 1840,[2] a storm blew a house roof off and into the rail corridor. The roof landed on the tracks at Mt Druitt, which affected the overhead electrical supply. Consequently, the track between Blacktown and Penrith was partially closed and Sydney Trains passenger train, 165-S, was held at Mt Druitt station. Passengers disembarked and continued their journey by other means.

Sydney Trains’ Train Crew Assignment Centre (TCAC) decided that the existing train crew would need to be relieved if the train was going to be held at Mt Druitt station for an extended time. TCAC called a driver and guard who were on a stand-by roster and offered them the extra shift. Both accepted and made their way to Central station. The guard signed on at 2000 and the driver at 2100.

Before going to Mt Druitt, the driver and guard completed a passenger service from Central to Hornsby. After this trip they were directed to Mt Druitt station to relieve the train crew on 165-S.

They travelled separately to Mt Druitt station. The guard arrived at 0128 and the driver at 0154. Both went to the country end of platform 3 where the previous train crew were waiting to be relieved. The driver received handover information about problems with the train from the previous driver. He was advised that:

- the overhead electrical supply was off

- the internal cab lights were not working

- the external lights were flashing on and off

- the pantographs were down and the pantograph pump was not responding

- the Metronet train radio was not working

- the faults had been reported to mechanical control.

The previous driver left the station and, at 0205, the driver unsuccessfully attempted to log into the train’s control system and turn on the internal cab lights. The guard was also unsuccessful in attempting to log in to the system.

As the train radio was not working, the guard and driver exchanged mobile phone numbers to enable communication between them. A network control officer (NCO) reported after the incident that he was unable to establish effective communication with the driver until he obtained the driver’s mobile number around 0500. Meanwhile, much of the communication from the signal box throughout the night was via the guard’s mobile phone or via the Mt Druitt station staff, who would walk down to the platform and speak to the driver.

At 0216, the driver walked to the train’s cab at the city end in an attempt to log into the train’s control system. He was again unable to do so. He phoned the guard and requested that they change ends. He returned to the country end at 0218, passing the guard on the platform who went to the city end of the train.

At 0257, overhead power was restored to all running lines. At 0311, a member of Mt Druitt station staff walked down onto the platform and told the driver that the signal box was trying to contact him. The driver phoned the NCO, who informed the driver that power was restored and that he should get ready to depart.

The driver again attempted to log into the train’s computer system, but was unable to do so. The driver phoned mechanical control about logging in and they gave him further instructions to try to rectify the fault. The driver’s login attempts were again unsuccessful. He was then advised to go to the cab at the city end and try to log in there.

At 0332, the driver walked from the country end to the city end and found the guard on the phone to mechanical control discussing the train’s computer system. They both tried to log in. Their attempts were unsuccessful. The driver made his way back to the country end of the train to try a similar process, but was again unsuccessful.

At 0349, the driver left the country end of the train and walked along the platform while speaking to mechanical control on his phone. Halfway along the platform he turned back and returned to the cab at the country end of the train.

A few minutes later, the driver walked from the country end towards the city end. Mechanical control sent a train technician to assist the driver. He arrived at 0352 and met the driver on the platform. Both the train technician and the driver then walked along the platform to the city end of the train where they attempted to get the train working. The train technician requested the driver assist him with the procedure. Once again, the attempt was unsuccessful.

At 0403, the driver and train technician changed from the city to the country end of the train. Both the driver and train technician worked on restarting the train. After a few attempts, they were successful in raising the pantographs. Other issues, such as the train radio, needed attention by the train technician. The train technician left the train at 0436 to get his laptop from the work van. The technician returned to the country end and was successful in restarting the train’s computer. This restored the destination indication panel on the train, but did not fix the train radio problem.

The driver left the train again to go up to the concourse level to the toilet. The driver was on the phone the entire time until returning to the train. At 0452, the guard received a call from the Rail Management Centre discussing problems with the train and asking to inform the driver to move the train soon. The guard spoke to the driver about this message. At 0453, a member of Mt Druitt station staff walked to the country end of the train and passed a message to the driver that the signal box was trying to contact him.

At 0455, an NCO spoke to the driver on his mobile phone and asked the driver if everything was good and if he was ready to go. The driver told the NCO about the problems with the train radio. Just as the driver was asking about his instructions and where he was going, the NCO ended the call to take another call. He then called back at 0458. During this call, he told the driver to operate the train to St Marys, terminate the train, and then return to Macdonaldtown Stabling Yard. The driver stated, ‘OK, I understand’.

The driver called the guard at 0502 and asked to change ends with him. The driver and train technician then walked together towards the city end of the train. At the same time, the guard walked towards the country end. The three met in the middle of the platform and talked for a few seconds. The guard assumed that they were changing ends not to move the train, but to rectify more problems. After a short conversation between the guard and the train technician, the driver and train technician continued to the city end of the train. This was the final change of ends before the driver moved the train.

The driver had changed ends seven times in 3 hours.

The guard was informed that the train could run without a functioning train radio - the NCO said, ‘it’s getting critical, we need him to move’. At 0505, an NCO called the driver and asked if the driver still had a problem. The driver said that they were about to conduct a continuity test after which they would be ready to depart. The NCO said to the driver, ‘(we are) trying to get you motivated, that’s all’.

The occurrence

The train technician, having completed his work, left the driver at the city end of the train at 0507 and departed the station. At 0511, an NCO called the driver and asked when he would be departing. The driver responded that they were departing ‘just now, just now’ but said he would talk with the guard first and probably depart ‘in five seconds’. Meanwhile, the guard called the driver on the train’s intercom system.

The guard informed the driver that he was in the wrong cab if they were heading to St Marys. The driver acknowledged that he heard this information. The driver and guard then discussed the continuity test before exchanging bell signals at 0512. The internal bell signals are used for communication between the driver and the guard. A single bell (all right) was given by the driver at 05:12:46; the guard returned this at 5:12:51.

Immediately after finishing the conversation with the guard, the driver engaged the power handle to 68% to move the train. The time was 0513:05. The train moved away from Mt Druitt station in the up running direction on the Down Suburban line[3] (Figure 1). The train was travelling in the wrong running direction. The driver said he had his head down and was focussed on the controls. The guard was at the door of the train as it moved away from the station. The guard said that the reason the focus was towards the platform was in case late running passengers attempted to get onto the train.

Figure 1: Night time view from Platform 3 (city end)

The white arrow shows the wrong running direction that train 165-S travelled on the Down Suburban line.

Source: Sydney Trains

At 0513:30, after the train had travelled 111 m, the driver adjusted the power handle to 49%, a normal setting for the train to coast. At the same time, NCOs were observing the train movements on their Train Visibility System screen. They observed that the train was heading in the wrong running direction. An NCO made a call to the driver via his mobile phone at 0514:38 and told him to stop the train immediately and not move it any further. The driver said that he would do so and applied the brakes immediately.

At the same time a freight train, CA63, about 4 km away was travelling on the same Down Suburban line towards 165-S. It had just passed through Blacktown station and was approaching Doonside. An NCO contacted the crew of the freight train and told them to stop. This train was stopped before Doonside station.

Before the freight train was stopped, it was travelling in the correct running direction with line-side signals providing the driver with indications along the route. It is likely the driver of the freight train would have reached a signal at stop before reaching the passenger train. This was because the presence of the passenger train would have been detected by the signalling system, setting the signals to stop between it and the freight train.

Meanwhile, the driver of the passenger train had no signals facing him and no mechanism warning him of the freight train ahead. The available defences were the awareness of the driver and guard on the train, and the vigilance of the NCOs watching the Train Visibility System screen in the signal box.

Post-occurrence events

The time was 0514:46 when 165-S came to a stand with the leading car (city end) located at 42.470 km. It had travelled 761 m since leaving the station. During the trip, the train had reached a maximum speed of 33 km/h.

At 0515, the guard made a call to the signal box and enquired whether the driver had authority to head in the wrong running direction. The guard was told that the driver did not have this authority. The NCO again phoned the driver and instructed him to hold the train until an Incident Rail Commander arrived.

At 0521, the Rail Management Centre Shift Manager instructed an Incident Rail Commander to attend. He arrived at 0545 and tested both train crew for the presence of alcohol. Both returned a negative result. The driver was requested to change ends and drive the train back to Mt Druitt station. Authority was given and, at 0614, the train departed, arriving at Mt Druitt station a few minutes later. Both crew were drug tested at 0633. These results were also negative.

__________

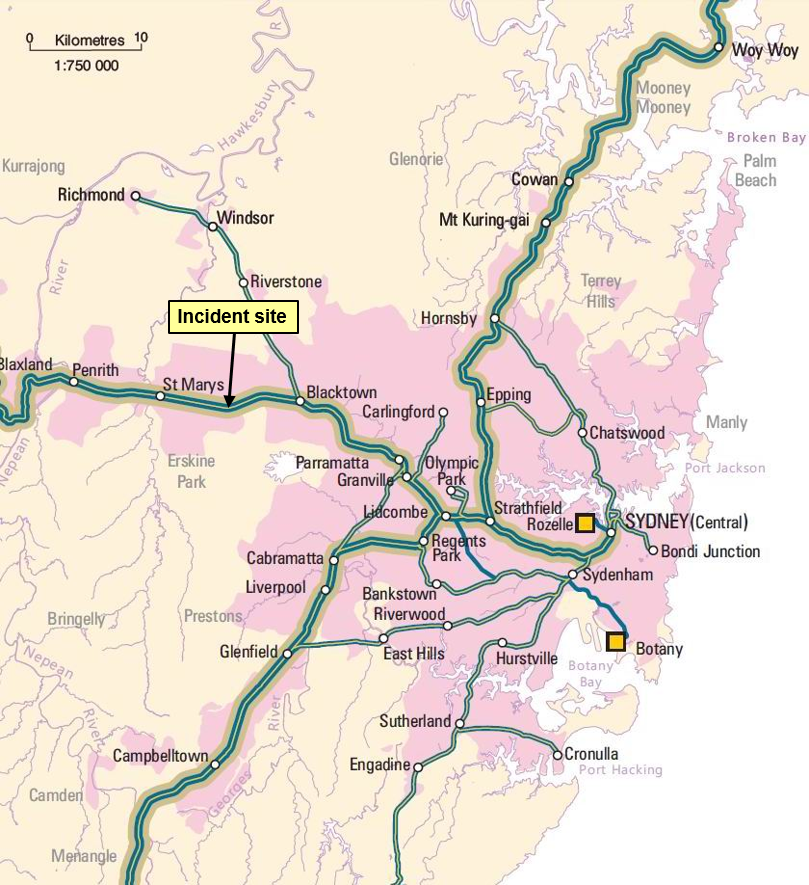

Incident location

The incident occurred at Mt Druitt station on the Down Suburban line. Mt Druitt is located 43 km west of Sydney (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Location of incident at Mt Druitt

This map shows the major railway lines in the Sydney metropolitan area including the western line where the incident occurred.

Source: Geoscience Australia

There were four platforms and four standard gauge lines at Mt Druitt station, the Up and Down Suburban lines and the Up and Down Main lines. Platform 3 is next to the Down Suburban line (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Line information Mt Druitt

The red arrow shows the direction that train 165-S travelled on the Down Suburban line.

Source: OTSI

Train information

Sydney Trains operated the train involved in the incident. The set number of the train was A19. On the day of the incident, it was completing run 165-S. The A-set or Waratah train is an electric multiple unit. It consisted of eight cars with a driving car at each end (Figure 4), two motor cars located next to each driving car, and two trailing cars in the centre of the train. Waratah trains first entered service on the NSW rail network in 2011.

Figure 4: A-set driving car

Source: Sydney Trains

Crew information

The driver and guard were based at Central station, Sydney. Both lived in the inner suburbs of Sydney and had less than 30 minutes travel time to work.

The driver was an experienced driver, starting as a metropolitan train driver in April 2005. He was familiar with the route, fully qualified and medically fit.

The guard was less experienced, having started as a guard in June 2013. The guard was qualified and medically fit.

The driver and guard had not previously worked together.

Environmental conditions

The storm that had caused the network delays the previous evening had long since passed by the time of the incident. Other than some rain showers between 0248 and 0258, there were no adverse weather conditions.

The overnight minimum temperature was 17.5°C as recorded by the Bureau of Meteorology at Horsley Park, approximately 10 km from Mt Druitt station.

It was still dark when the incident occurred at 0513. Sunrise was at 0553.

Network management

NCOs in the Blacktown, Penrith, and St Marys signal boxes control train movements in the area around Mt Druitt. The train controller in the Rail Management Centre at Central also has visibility of train movements throughout the network.

Train maintenance

A private company, Downer Rail, was the contracted entity responsible for A-set train maintenance at the time of the incident. On the morning of the incident, a train technician from Downer Rail attended the site and assisted the driver to restart the train. He left before the driver moved the train.

Introduction

The driver of passenger train 165-S drove the train in the wrong direction for 761 m. Previously the guard had warned the driver that he was in the wrong cab if he was going to St Marys. The guard did not take any action when the driver started driving in the wrong running direction. An NCO quickly realised the train was heading in the wrong running direction and contacted the driver to stop 165-S.

The driver did not realise the direction that the train was facing before moving the train. This was despite being familiar with the station, the route that he was to operate over, and the guard reminding him that he was at the wrong end of the train. A combination of changing ends a number of times, the length of time at the station, a high workload, and fatigue are the likely reasons he lost awareness of which way he was facing. The driver also felt under pressure to get the train moving after several telephone conversations with NCOs.

This section examines the contributing factors that led to the driver’s action including his work schedule and some preconditions for his unsafe act. It also explores the role of the guard and Sydney Trains fatigue management system.

Factors affecting the actions of the train crew

Time of day

The period between 0200 and 0600 is well established as a period of reduced performance. This is due to the effects of the circadian cycle, which predisposes humans to sleep during the night and be wakeful during the day. When we reverse these activities and work through the night and sleep during the day, we compromise the quality and the quantity of sleep, as well as the quality of the work performed. Thus, time of day creates an additional element of fatigue risk in 24−hour rail operations. The increase in fatigue and the deterioration in performance with time on task have been shown to occur more rapidly overnight.[4]

Another factor that affected the driver’s performance was the night environment. Although there was adequate lighting around the platform and train, the darkness limited visual cues about the direction he was facing. The signal that was closest to the driver was facing the other way. It was designed for trains travelling in the Down direction on the Down Suburban line. The driver said he could not see or did not notice this signal.

Fatigue impairment

In the context of human performance, fatigue is a physical and psychological condition primarily caused by prolonged wakefulness and/or insufficient or disturbed sleep.[5] The National Transport Commission recognises five main factors contributing to fatigue impaired work performance:

- the duration of a duty period (time on task), and the rest breaks within and between shifts

- inadequate sleep (or sleep debt), which results from inadequate duration and quality of prior sleeps

- circadian effects, which involve working and sleeping against natural body rhythms that normally program people to sleep at night and be awake and work during the day

- the type or nature of the task being undertaken (workload)

- the work environment.

These factors are compounded by a person’s body clock, environmental conditions, stress, age and personal health and fitness.[6] Fatigue can have a range of influences on performance, such as decreased short-term memory, slowed reaction time, decreased work efficiency, reduced motivational drive, increased variability in work performance, and increased errors of omission.[7] Transport accident investigation agencies have identified fatigue impairment as a causal factor in many accidents and incidents.

The driver indicated during an interview that at the start of the shift he felt exhausted, then while he was working on the train ‘adrenaline kicked in’. However, as the shift progressed, he got tired. He said that at the time of the incident he ‘felt drowned - exhausted in the cab'. As an explanation for why this incident happened, he said it was ‘particularly to do with so many hours without sleep’. It should be noted that the driver had a personal responsibility to declare himself unfit for work if he felt that his performance would be affected by fatigue. Research has shown that assessing your own level of fatigue is difficult.[8] There are also a number of reasons why train crew are reluctant to decline an extra shift. Although not indicated by the crew in this incident, common reasons cited by train crew for accepting shifts when fatigued include the loss of income and gaining a reputation as someone who is not reliable.

The scheduling of drivers to work in the early hours of the morning is unavoidable. Knowing the risks associated with early morning shifts is important to optimise the rostering of train crew. The selection of this driver to work this shift increased his risk of error.

Given the driver’s actions and his reported state of fatigue impairment, as well as the established links between fatigue impairment and increased error, Sydney Trains’ management of fatigue risk was investigated.

Driver’s roster

An examination of the driver’s roster, including the incident shift, showed that he had worked 12 of the previous 14 days. In addition, this shift, a stand-by shift, was his tenth consecutive shift. The previous shifts all started in mid-afternoon or in the evening. He worked no morning shifts. This meant he was in a pattern of going to bed around 0100 and sleeping in. He said that if he had not worked this shift he would have gone to bed about midnight. The incident occurred at 0513, a time when he had planned to be sleeping.

The driver said that he started the day about 0800 and spent the day visiting friends. Rostered as a stand-by driver he received a call from train crewing at 2022.

Some of the rostering principles set down by Sydney Trains are:

- maximum shift length is set as 9 hours for the driver of a suburban train

- workers new to shift work or returning should not be rostered on night work or early morning for their first shift

- total hours worked should be no more than 48 hours per week

- break of 11 hours between shifts

- maximum number of shifts is 12 in a 14 day period

- limit night shifts and early morning starts

- schedule frequent breaks during a night shift or if the work involves sustained mental or physical activity.

Although the driver considered that he was affected by fatigue when the incident occurred, Sydney Trains use of bio-mathematical modelling did not predict that the driver’s roster would place him at risk. Their assessment of the suitability of the roster for managing fatigue risk was based primarily on the use of a bio-mathematical fatigue modelling program known as the Fatigue Audit Interdyne (FAID).

Bio-mathematical models attempt to predict the effects of different working patterns on subsequent job performance, with regard to the scientific relationships between work hours, sleep, and performance.[9] FAID does not predict fatigue but rather predicts a sleep opportunity, demonstrating only that the organisation has provided employees with an adequate opportunity to sleep, producing a work-related fatigue score.[10]

When evaluating rosters, there are a number of documented limitations with over-reliance on bio-mathematical models such as FAID. Because the distribution of fatigue across a given population of employees working the same roster is significant, it is difficult to generalise from the average data generated by a bio-mathematical model. As noted by the NSW Independent Transport Safety Regulator (ITSR):

…fatigue models are appropriate to use as one tool to help evaluate group rosters to help identify how aspects of fatigue exposure are distributed. Model outputs... should never be the sole basis for a safety risk management decision regarding work hours.[11]

FAID, along with other bio-mathematical models, is a useful tool to account for hours of sleep opportunity provided, thereby providing an indication of fatigue exposure across a group of employees. It cannot account for the hours of sleep actually achieved by individuals, nor for the quality of that sleep. These additional factors necessitate the use of multiple layers of controls to manage fatigue-related risk.

Sydney Trains’ management system included policies, procedures, and training to address train crew fatigue impairment. These systems provide guidance for management and employees to ensure there is an awareness of countermeasures in this area. This case should serve as an opportunity to review the rostering of train crew, especially those called in on the stand-by roster.

Time pressure

For most transport operators there is a balance between on-time running and having a safe system. ‘To achieve both safety and on-time running requires the ability to identify hazards that can disrupt services or compromise safety and efficiently manage the risks those hazards create’.[12]

Both train crew received a number of calls from NCOs throughout the shift. The train was expected to be moved once power was restored to the electrical supply. It is likely that NCOs were concerned about delays to the upcoming morning peak. This concern was communicated to both the guard and the driver.

The conversation between the NCO and the driver two minutes before he eventually moved the train was as follows:

| Person | Voice recording |

| NCO | ‘Are you right to depart though?’ |

| Driver | ‘Yeah, I have just confirmed with the box’. |

| NCO | ‘So how long before you depart?’ |

| Driver | ‘Just now, just now’. |

| NCO | ‘So are you on the move?’ |

| Driver | ‘Yes - no. I am just going to confirm with the guard … probably 5 seconds’. |

| NCO | ‘Ok thank you’. |

The driver said later, 'I felt under pressure to get moving from the box. I moved a few seconds after talking to the (signal) box’.

Communication was hampered by the train radio not working. Initially, this meant information to the driver was relayed via the guard and station staff. Eventually communication was made directly to the driver via his mobile phone. Normally drivers must turn off their mobile phones when driving, but an exception is made when the train radio is not working.

Area control also contacted the guard. The guard was told, correctly, that the train could be moved without a working train radio. The NCO asked that the driver be reminded that a document about this had been released the previous week.[13] The guard was also told that, ‘it’s getting critical that we need him to move’.

Research suggests that a call from a controller to explain a delay increases pressure on the driver to perform.[14] ‘In general, under stress, attention appears to channel or tunnel, reducing focus on peripheral information and tasks and centralising focus on main tasks’.[15] The tunnelling of attention can be a good thing or a bad thing for performance. In this case, the driver said he was completely focussed on the controls in front of him. It is likely that this contributed to him confusing the direction in which he was about to move.

Workload

The driver experienced a period of sustained high workload during his time at Mt Druitt station in the hours leading up to the incident. For over three hours, he made or received a large number of phone calls communicating with network control, train maintenance and the guard. He was on his feet during this time, either standing in the train cab, walking to the other end of the platform or walking up to the concourse.

Research has shown that a high workload can result in slower task performance and errors. ‘Unusual or high workload situations and situations where people are under time pressure can contribute to fatigue related incidents. Rather than causing fatigue in the traditional sense, workload has been described as a factor which can either mask or augment the effects of fatigue. People working under time pressure, or with a high workload, are most likely to make errors at the time of day that this incident occurred.’ [16]

Time at station

The amount of time the driver spent at the station before starting to drive may have affected his performance. The driver had been at Mt Druitt station since 0154 and, for the majority of the time, working and problem-solving to get the train started. For three hours, his focus of attention was directed at fixing problems with the train. The driver’s attention was away from the routine task of driving. When he departed, it was likely his mind was still engaged with the previous task he had spent so much time working on.

The driver said at interview that, after eventually moving the train, ‘when I put my head up, something was weird in my brain. I saw we were not on the right path, with 10 years’ experience as a driver. So everything it was upside down’.

Research suggests that an extended time spent at the station serves to dislocate the driver’s attention from the primary task and safe working. This research found that inattentiveness was deemed to arise primarily from the consequence of disengagement from an active driving state, which gives rise to the process of distraction and reduced situation awareness.[17]

Multiple end changes

Since arriving at Mt Druitt station at 0154, the driver had changed ends seven times. On another occasion, he walked half way along the platform and returned. He had also left the train and walked up to the concourse on two occasions. The timing of driver movements is shown in the table below:

| Time | Driver actions |

| 0154 | Arrives at Mt Druitt Station and goes to country end of train |

| 0211 | Leaves train and goes up to concourse level |

| 0216 | Changes from country to city end |

| 0218 | Changes from city to country end |

| 0332 | Changes from country to city end |

| 0342 | Changes from city to country end |

| 0347 | Starts to change from country to city end, stops half way and returns |

| 0351 | Changes from country to city end |

| 0403 | Changes from city to country end |

| 0448 | Leaves train and goes up to concourse level |

| 0502 | Changes from country to city end |

| 0513 | Driver starts driving wrong way from city end of train |

It is likely that changing ends on multiple occasions confused the driver. After the train technician arrived, the driver and train technician changed ends twice together (0403 and 0502) and the driver may have thought he would be returning to the country end. He said he thought the train technician would be travelling to St Marys with him. After the train technician left the driver in the cab, the driver should have returned to the country end. Instead the driver prepared to move the train, exchanged bell signals with the guard, received a phone call from the signal box and an intercom call from the guard, then moved the train shortly afterwards.

The role of the guard

The use of a driver and guard is an important measure to mitigate the risk of driver error. ‘Train Crew are responsible for the safety of all passengers on the train, and must be prepared to stop a train immediately if an emergency situation arises. The Train Crew must assist each other to provide for the safety of all passengers’.[18]

A guard provides a level of redundancy in the system. It is essential that guards are not reluctant to take action in an emergency.

The guard was less experienced than the driver. They had not previously worked together. The guard reminded him at least twice that he was in the wrong end of the train if they were going to travel to St Marys. The driver recalled that the guard had told him this. It seems that the driver did not assimilate the significance of the advice, given all that was going on at the time.

The guard took no action when the train started moving in the wrong running direction. This was despite knowing the train was going the wrong way. The guard thought that the driver might have received authority to do this. After the incident, the guard contacted the Rail Management Centre to ask them if they had given authority from the driver to go in the wrong running direction, perhaps being issued a Special Proceed Authority. The guard was told that they had not given any such authority to the driver.

If the guard thought the train was going in the wrong running direction a number of actions could have been taken. These included:

- calling the driver and asking him what he was doing

- giving a bell signal, of two bells, which tells the driver to stop immediately

- operate the emergency brake isolating cock to bring the train to a stand.

Instead, the guard made a decision to watch for passengers on the platform that may have been trying to board the train before it moved off. There were few passengers on the station at the time.

Since the late 1970s, aviation accident investigation agencies have identified ‘authority gradients’ existing between crew contributing to incidents. One significant aviation accident where an authority gradient was a contributing factor was the collision of two Boeing 747s at Tenerife Airport, in 1977. The crash killed 583 people, making it the deadliest accident in aviation history.

‘In a study of 249 airline pilots in the United Kingdom, nearly 40 percent of first officers stated that they failed to communicate safety concerns to their captains on more than one occasion for reasons that included a desire to avoid conflict and in deference to the captain’s experience and authority’.[19]

In 2003, a passenger train derailed at Waterfall, NSW killing 7 persons including the driver. The Special Commission of Inquiry set up to investigate this accident found that an authority gradient existed between the guard and driver. This was one of the factors that discouraged the guard from responding in the emergency. One recommendation discussed improving driver and guard training to encourage teamwork and discourage authority gradients.[20]

Both driver and guard from the Mt Druitt incident had received training about effective communication and teamwork, the guard most recently in 2013.

Track configuration

The track configuration between Westmead and St Marys is different to many other areas in the Sydney metropolitan network. In most multiple track areas, the sequence of tracks will generally be an Up line next to a Down line. The track configuration at Mt Druitt placed both Down lines next to each other, and both Up lines next to each other. This has caused confusion to some drivers and maintenance staff in the past. There is no evidence that this contributed to the driver moving the train in the wrong direction.

__________

- Williamson, A., Lombardi, D.A., Folkard, S., Stutts, J., Courtney, T.K. & Connor, J.L. (2011). The link between fatigue and safety. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 43, pp. 498-515.

- National Transport Commission (2008). National Rail Safety Guideline. Management of Fatigue in Rail Safety Workers. p.5.

- Ibid.

- Battelle Memorial Institute (1998). An Overview of the scientific literature concerning fatigue, sleep, and the circadian cycle. Report prepared for the Office of the Chief Scientific and Technical Advisor for Human Factors, United States Federal Aviation Administration.

- Van Dongen, H.P.A., Maislin, G., Mulligan, J.M., Dinges, D.F. (2003). The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: Dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep. Vol. 26. pp.117-126.

- Dawson, D., Noy, Y.I., Harma, M., Akerstedt, T. & Belenky, G. (2011). Modelling fatigue and the use of fatigue models in work settings. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 43, p. 551.

- Ibid., p. 553.

- Independent Transport Safety Regulator (2010). Transport Safety Alert 34 - Use of bio-mathematical models in managing risks of human fatigue in the workplace.

- McInerney, P.A. (2005) Final Report of the Special Commission of Inquiry into the Waterfall Rail Accident Vol. 1 p. xviii

- Sydney Trains. (2015) Defective Train Radios. General Instruction – Operations Directorate 23/2015.

- Naweed, A. (2013). Psychological factors for driver distraction and inattention in the Australian and New Zealand rail industry. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 60, pp.193-204.

- Staal, M. A. (2004) Stress cognition and human performance – A literature review and conceptual framework. NASA Technical Memorandum. NASA/TM—2004–212824. p.31.

- National Transport Commission (2008). National Rail Safety Guideline. Management of Fatigue in Rail Safety Workers. p.5 -8.

- Naweed, A. (2013) Op. Cit. p.199.

- RailCorp. (2013) TWP 100 Responsibilities of Train Crew. TOM Notice No. 16.

- National Transportation Safety Board. (2011) Safety Recommendation A-11-39. p.3.

- McInerney, P.A. (2005) Final Report of the Special Commission of Inquiry into the Waterfall Rail Accident Vol. 1 p. 339.

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the wrong running direction of a Sydney Trains passenger service, 165-S, that occurred at Mt Druitt, NSW on 12 March 2015. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

Safety issues, or system problems, are highlighted in bold to emphasise their importance. A safety issue is an event or condition that increases safety risk and (a) can reasonably be regarded as having the potential to adversely affect the safety of future operations, and (b) is a characteristic of an organisation or a system, rather than a characteristic of a specific individual, or characteristic of an operating environment at a specific point in time.

Contributing factors

- The driver lost awareness of the direction he was to travel due to changing ends seven times in 3 hours while dealing with tasks not usually associated with driving while the train was stationary at Mt Druitt station.

- The driver spent over 3 hours at Mt Druitt station performing other tasks before he started driving, his focus of attention directed at fixing problems with the train. When he departed, it was likely his mind was still engaged with the previous task.

- The driver experienced a period of sustained high workload during his time at Mt Druitt station in the hours leading up to the incident.

- The driver felt that he was under pressure to move the train after receiving multiple telephone calls questioning when he would be moving.

- It is likely that the driver of train 165-S was experiencing some level of fatigue impairment when he started driving the train in the wrong running direction.

- The time of day when the incident occurred is known to be in the low range of the circadian sleep cycle.

- Sydney Trains' fatigue management processes were ineffective in identifying the fatigue impairment experienced by the driver. [Safety issue]

- The guard did not take action, either to stop the train or warn the driver, when the driver started driving in the wrong running direction.

Other factors that increased risk

- The driver did not assimilate information from the guard, who told him, on two occasions, that he was in the wrong end for the instructed direction of travel.

Other findings

- The NCO recognised that train 165-S had started moving in the wrong running direction. The timely action by the NCO in stopping both trains (165-S and CA63) was fortunate.

Depending on the level of risk of the safety issue, the extent of corrective action taken by the relevant organisation, or the desirability of directing a broad safety message to the rail industry, the ATSB may issue safety recommendations or safety advisory notices as part of the final report.

Fatigue management

Sydney Trains' fatigue management processes were ineffective in identifying the fatigue impairment experienced by the driver.

ATSB Safety Issue No: RO-2015-005-SI-01

ATSB Recommendation No: RO-2015-005-SR-04

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- Downer Rail

- Sydney Trains

References

Battelle Memorial Institute (1998). An Overview of the scientific literature concerning fatigue, sleep, and the circadian cycle. Report prepared for the Office of the Chief Scientific and Technical Advisor for Human Factors, United States Federal Aviation Administration.

Dawson, D., Noy, Y.I., Harma, M., Akerstedt, T. & Belenky, G. (2011). Modelling fatigue and the use of fatigue models in work settings. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 43, pp 549-564.

Independent Transport Safety Regulator (2010). Transport Safety Alert 34 - Use of bio-mathematical models in managing risks of human fatigue in the workplace.

McInerney, P.A. (2005). Final Report of the Special Commission of Inquiry into the Waterfall Rail Accident Vol. 1.

National Transport Commission (2008). Management of Fatigue in Rail Safety Workers. National Rail Safety Guideline.

National Transportation Safety Board. (2011). Safety Recommendation A-11-39.

Naweed, A. (2013). Psychological factors for driver distraction and inattention in the Australian and New Zealand rail industry. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 60.

RailCorp. (2013). TWP 100 Responsibilities of Train Crew. TOM Notice No. 16.

Staal, M. A. (2004). Stress cognition and human performance – A literature review and conceptual framework. NASA Technical Memorandum. NASA/TM—2004–212824.

Sydney Trains – RailSafe website. (2015). <https://railsafe.org.au/glossary>

Van Dongen, H.P.A., Maislin, G., Mulligan, J.M., Dinges, D.F. (2003). The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: Dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep, 26, pp117-126.

Williamson, A., Lombardi, D.A., Folkard, S., Stutts, J., Courtney, T.K. & Connor, J.L. (2011). The link between fatigue and safety. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 43, pp 498-515.

Submissions

Under Part 4, Division 2 (Investigation Reports), Section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 (the Act), the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. Section 26 (1) (a) of the Act allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to:

- Downer Rail

- the Downer Rail train technician

- Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator

- Pacific National

- Sydney Trains

- the train crew of 165-S

Submissions were received from Downer Rail, the Office of National Rail Safety Regulator, Pacific National, Sydney Trains, and the train crew of 165-S.

The submissions were reviewed and where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2016

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |