What happened

On the morning of 20 March 2015, the pilot of a Piper PA 25-235/A9 Pawnee aircraft, registered VH-NLP, departed a private airstrip near Derrinallum to conduct insect baiting operations on a property near Darlington, Victoria. Shortly after commencing that task, the aircraft collided with terrain and was destroyed by impact forces and a post-impact fire. The pilot, who was the sole occupant, was fatally injured.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that while positioning the aircraft for a baiting run, the pilot inadvertently descended below the normal application height over an adjacent paddock. While recovering from this loss of height and avoiding terrain, the aircraft probably stalled and entered an incipient spin at a height from which recovery was not possible before colliding with terrain.

There was no evidence of any pre-existing mechanical defect with the aircraft or engine that could have contributed to the accident. However, the aircraft was being operated outside the flight envelope as it exceeded the design maximum take-off weight. In addition, the conditions were conducive for the formation of carburettor icing.

Safety message

Operators and pilots are reminded of the hazards associated with agricultural low-level flying and the increased risk of collision with terrain. The ATSB highlights the importance to pilots and operators of ensuring that their aircraft’s weight and balance is within specified limits, and understanding the effects of operating outside the flight envelope on the aircraft’s flying characteristics. This accident is also a reminder of the importance of monitoring environmental conditions and the associated risk of carburettor icing.

Photograph of VH-NLP

Source: The operator

On 20 March 2015, a Piper Aircraft Corporation PA-25-235/A9 Pawnee aircraft, registered VH‑NLP (NLP), was being prepared for an agricultural flight from a private airfield near Derrinallum, Victoria. A witness reported observing an estimated total of about 100–120 l of fuel on board, and load of about 450 kg of insect bait. The witness observed that the pilot appeared to be well rested and enthusiastic about the task.

The planned flight was an insect baiting operation, consisting of spreading a poison-infused wheat product. This was to be carried out on a farming property near Darlington, Victoria, over three adjoining paddocks in an east-west direction. The plan was for the pilot to conduct the bait application in a left racetrack pattern,[1] at about treetop level.

At about 0850 Eastern Daylight-saving Time,[2] NLP departed for the 10-minute flight to Darlington. The operator considered the wind to be calm at the time NLP departed Derrinallum. A witness at the accident site indicated that the conditions were calm at about 0900–0915, when they heard the aircraft. They noticed that the wind did come up later in the morning. Bureau of Meteorology weather observations were available for Mortlake, about 15 km to the west of the farming property. At about the time of the bait application operation, the Mortlake recorded weather indicated that the wind was from the west at 7 kt, the temperature was 12.3 °C and that the dewpoint[3] temperature was 10 °C.

Several witnesses observed and heard the aircraft operating in the area of the three paddocks between about 0900 and 0915. One witness, who was travelling along a nearby highway to the south-east of the three paddocks, observed NLP at treetop height, heading west. They then observed it rolling left and right before suddenly descending. Black smoke was seen by witnesses coming from a paddock in the area where NLP had been operating. The aircraft impacted terrain, out of sight of the witnesses, at about 0915.

The pilot, who was the sole occupant, was fatally injured and the aircraft was destroyed by impact forces and a post-impact fire. The accident was not considered survivable.

Operational aspects

Pilot information

The pilot was appropriately qualified for the flight, holding a Commercial Pilot (Aeroplane) Licence, a Class 2 Agricultural Rating (Aeroplane), and a Class 1 Aviation Medical Certificate. The pilot completed their agricultural rating on 9 April 2014, which included their 2-yearly flight review. The pilot had a total aeronautical experience of about 281 hours, about 17 hours of agricultural flying and about 15 hours in NLP.

After obtaining an agricultural rating in Victoria, the pilot was employed for about 4 months by an operator in Queensland. Although the pilot performed a number of training and general flights with that operator, there were no recorded agricultural flights during that period. The pilot returned to Victoria in August 2014, and performed various duties. These included agricultural operations and aerial work through until November 2014.

The pilot’s most recent aerial agricultural operations occurred about 5 months prior to the accident in October 2014. That involved three baiting flights and two flights spraying liquid chemical. The pilot then completed three general flights in January 2015. Of these, the last entry in the pilot’s logbook was for a flight on 26 January 2015. The pilot’s logbook did not include a ferry flight undertaken in NLP on the day prior to the accident.

An aerial agriculture instructor who had flown with the pilot stated that, although the pilot was conscientious and deemed safe for flying agricultural operations, there were particular situations where the pilot’s lower level of experience became evident. These situations, which were reported to sometimes be observed in other ‘junior’ agricultural pilots, included difficulty managing the aeroplane’s attitude during turns and anticipation of a pending aerodynamic stall.[4]

Aircraft information

Piper Aircraft Corporation PA-25-235 Pawnee NLP was manufactured as a single-seat aircraft in the United States in 1965, and certified in the normal category. It was converted to an ‘A9’ variant in Australia in 1983 under a Civil Aviation Safety Authority Supplemental Type Certificate, and certified the normal and agricultural categories. This conversion included the installation of a second seat, replacement of the fabric-covered wings with metal wings and a larger chemical hopper.

The last periodic inspection was carried out on 5 August 2014 at 8,762.8 flying hours.

The Supplemental Type Certificate for the PA25-235/A9 detailed a maximum take-off weight of 1,315 kg. Based on the reported fuel and insect bait on board for the flight, the ATSB estimated that the aircraft departed at about 102 kg over the approved maximum take-off weight at take-off. Similarly, based on a planning fuel use of 60 l/hr and a ‘best guess’ metered bait application rate of 15 kg/hectare, it was estimated that the aircraft was about 39 kg over its maximum take-off weight after the first bait application run. Exceeding operational limitations can affect an aircraft’s handling and performance, reducing the normal operational safety margins. Depending on the magnitude of the exceedance, it can also impose significant structural loads in excess of the aircraft’s design loads. In turn, this can reduce the aircraft’s effective service life and potentially cause structural failure.

Preparation for the operation

Several days prior to the accident, the operator contacted the property owner to discuss the planned baiting job. The operator reported also taking the opportunity to carry out an airborne survey of the paddocks that were to be baited by the pilot. The operator recalled meeting with the pilot for a briefing on the afternoon before the planned flight. The briefing was reported to include a discussion of the boundaries of the paddocks that were to be baited, the powerlines and on the pre‑programming of the aircraft’s global positioning system equipment.

On-site examination

Accident site

The wreckage was located in the eastern-most paddock of the three to be baited. Examination of the accident site indicated that NLP impacted terrain nose-down, in an almost vertical orientation. The aircraft came to rest about 7 m from the initial impact point. The forward fuselage and cockpit sustained significant damage as a result of the initial impact, and a post‑impact fire consumed the the internals of the aircraft’s global positioning system equipment, the majority of the fuselage and the inboard wing sections (Figure 1). Damage to the leading edge of each wing also indicated a vertical impact. ATSB analysis based on estimates of the aircraft’s speed, the almost vertical impact angle and the energy absorbed by the aircraft indicated that the impact forces imparted to the pilot would normally be expected to result in fatal injuries.

Examination of the propeller, along with evidence from the impact crater, indicated that the propeller was rotating under a level of power at the time of impact. Flight control continuity was confirmed. Due to the level of damage, the flap position could not be determined.

No pre‑existing anomalies were identified at the accident site that would have precluded normal operation of the aircraft.

Figure 1: Aircraft wreckage (looking east), showing the lower surface of the aeroplane. Note the significant damage to the forward fuselage and cockpit area and the extent of the fire damage to the fuselage and inboard wing sections

Source: ATSB

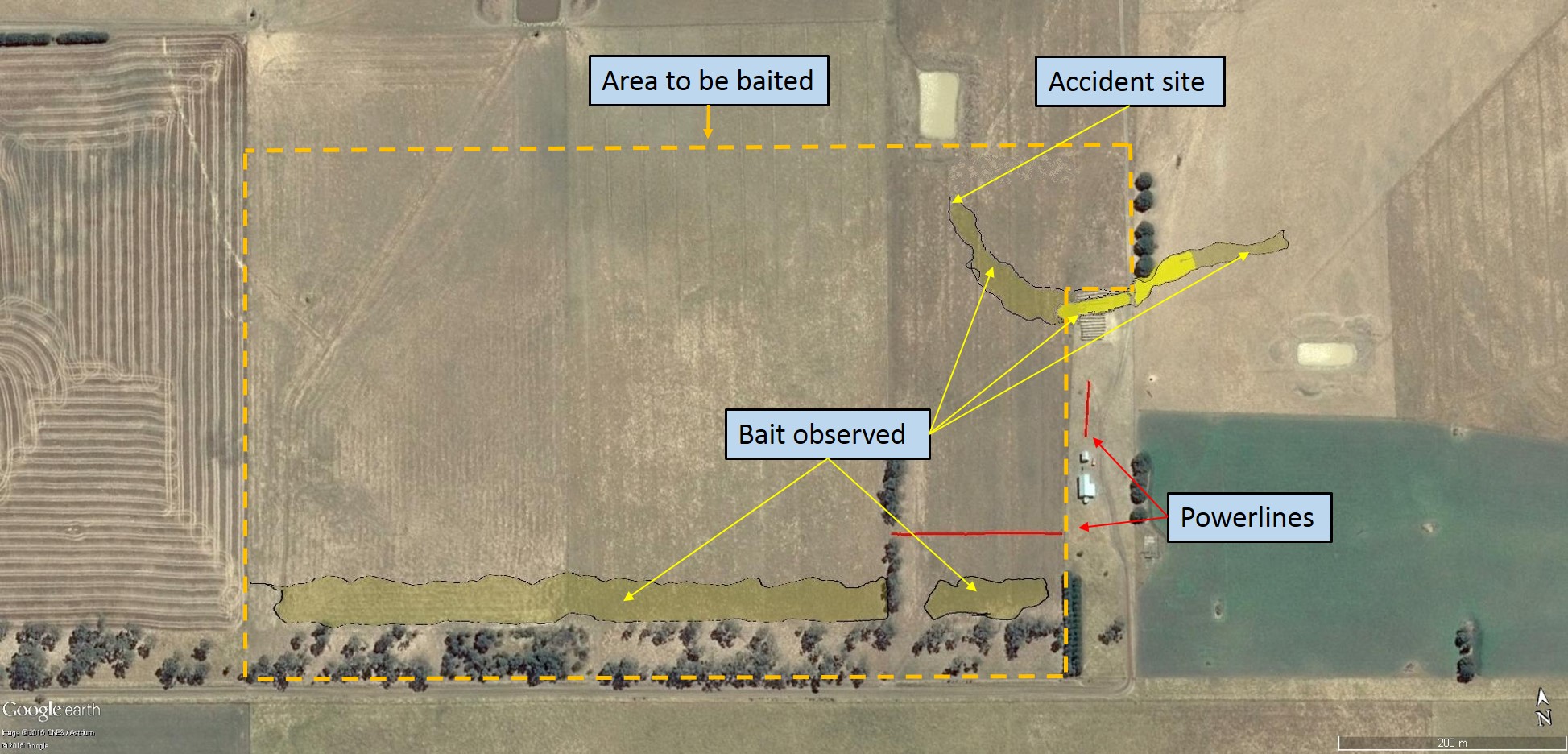

Insect bait was found in a straight and regular swathe along the southern fence line of the paddock, consistent with a bait application run (Figure 2). This swathe ran for the entire length of the planned baiting area and was about 36 m wide. Additionally, a bait swathe of varying width and density from the middle of the adjacent paddock was observed outside and to the top‑right of the baiting area. This continued in an arc to the initial impact point. This swathe initially decreased from about 16 m down to 7 m wide, then increased to 30 m wide before tapering off towards the accident site.

Figure 2: Area to be baited (outlined by the yellow dashed line), with dispensed bait shaded in yellow and higher-concentration bait shown as bright yellow

Source: Google earth, modified by the ATSB

Survivability and post-mortem results

The forensic pathologist who conducted the pilot’s post-mortem examination concluded that the pilot succumbed to the effects of fire and impact-related injuries. No abnormalities were identified that could have led to pilot incapacitation. Toxicology results did not identify any substances that could have impaired the pilot’s performance.

__________

- In a left racetrack pattern the aeroplane flies in an anticlockwise rounded rectangular path (when viewed from above), making wider turns than in a back-and-forth pattern.

- Eastern Daylight-saving Time (EDT) was Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) + 11 hours.

- Dewpoint: the temperature at which water vapour in the air starts to condense as the air cools. It is used, among other things, to monitor the risk of aircraft carburettor icing or the likelihood of fog.

- Aerodynamic stall: occurs when airflow separates from the wing’s upper surface and becomes turbulent. A stall occurs at high angles of attack, typically 16˚ to 18˚, and results in reduced lift.

Introduction

From witness information and examination of the accident site, it is evident that during the turn onto the second bait application run, the pilot lost control of the aircraft and was unable to recover before impacting the ground. The observed wing rock and descent was consistent with an aerodynamic stall and wing drop.

Examination of the aircraft and engine did not identify any anomalies that would have precluded normal operation, or that would have required the pilot to jettison the hopper load to the east of the intended bait application area. The wind at the time was not considered significant to the baiting operation.

This analysis will consider the factors with the potential to have contributed to the loss of control, including the potential influence of the aeroplane weight and loss of engine power due to carburettor icing.

Interpretation of the flight path

Set-up for and initiation of the second bait application run

Following the first bait application run, the pilot repositioned the aircraft for the next swathe along the paddocks, which was intended from east to west. The location and orientation of the bait application outside the intended area was consistent with its commencement prior to the beginning of the planned baiting run, as the pilot was finalising the repositioning turn. The spread width of the bait (see the following discussion) was consistent with the aircraft being at a lower height than for the previous run. The ‘track’ of the bait appeared to indicate that the pilot may have been attempting to avoid the tree line at the north‑eastern corner of the area to be baited. The increased bait concentration in the vicinity of those trees was consistent with the pilot jettisoning the load, as opposed to a normal application, which is at a metered rate.

Examination of the second bait application run

The spread width of the bait throughout the initial application run was about 36 m. Consistent with the aircraft owner’s standard bait application height of between treetop height and 100 ft (30 m), a witness observed VH- NLP (NLP) conducting runs at treetop height, or about 50 ft (15 m) above ground level. This reported height, and the known spread width on the first run, was used as a basis for determining the approximate height of NLP between the grain release in the adjacent paddock through to the accident site.

The spread width decreased from 16 m to 7 m, before increasing again to a width of 30 m. This indicates that NLP was below the previous application height, and continued to descend before climbing until about 70 m from the accident site. From this position the aircraft descended and impacted the ground. This is consistent with an attempt by the pilot to regain height after descending in the latter stages of the repositioning turn.

Reason for the height loss and jettison of the load

In an effort to understand the reason for the commencement of the bait application before entering the intended baiting paddock, the ATSB considered whether the pilot may have been momentarily confused by the apparent similarity of the respective tree lines immediately east of the area to be baited, or concerned with the powerlines on and near the south-eastern boundary of the area. The tree lines were each outside the area and the pilot had correctly ceased the first application run before passing over and east of the south-eastern tree line. In addition, the first application run passed close to the powerlines, and the pilot could be expected to have been aware of their location. On this basis, the ATSB concluded that it was unlikely the pilot misinterpreted the relevance of the location of the north‑eastern tree line, or would have been overly concerned with the location of the powerlines, when setting up for the application run.

In respect of the jettison of the bait, the ATSB considered whether the pilot may have unintentionally descended lower than planned or mishandled the repositioning turn. The pilot had relatively low total aeronautical experience and low and interrupted experience in agricultural operations. In addition, an aerial agricultural instructor advised that, similar to the instructor’s experience with other less-experienced agricultural pilots, the pilot at times had difficulty maintaining attitude in turns and anticipating an impending aerodynamic stall. The instructor reported that this was a particular risk when low-experience pilots were not current in agricultural‑type operations. It is not possible to quantify the effect of the pilot’s more recent, non‑agricultural flights in January 2015 on their handling of the aircraft in the baiting operation.

Another reason for the pilot to jettison the load was a loss of engine power. In this regard, although there were no engine anomalies identified that would have precluded normal operation, the ambient conditions were conducive to serious icing at any power setting. Carburettor icing can lead to a loss of engine power (see the subsequent discussion). However, the time between the accident and examination of the wreckage allowed sufficient time for any ice, if present, to have melted.

Aerodynamic stall and loss of control

Flying at low-level gives very little or no margin to recover from unexpected events, such as aerodynamic stalls or other losses of control. Height loss from a stall in general aviation aeroplanes, assuming correct recovery technique and expectancy of the pending stall, is generally 100–350 ft (30–107 m). Therefore, stall prevention (including maintaining airspeed) is essential at low heights.

One of the limitations of stall training and practice is that stalls are generally expected by students and follow a routine pattern. For unexpected or non-routine situations, a pilot will be focussed on the task at hand or perhaps a developing situation and potentially miss the available cues. In this accident, this could have included the pilot focussing on the unintended loss of height during the repositioning turn. Pilot knowledge and skill in recognising a developing stall situation, and responding effectively, is an essential element of flight safety in any operation.

NLP travelled a relatively short 70 m across the ground after the apparent attempt to regain height until impacting the ground. The physical evidence at the site indicated that the aircraft was inverted in an almost vertical, nose-down attitude at impact. The short distance between the initial point of impact with the ground and location of the main wreckage indicated low speed at that time.

Loss of control as a result of an aerodynamic stall could not be definitively proven. However, the low-level flight and manoeuvring by the pilot leading up to the loss of control increased the risk that they might miss any cues of an impending stall. The orientation of, and damage to the aircraft at impact, and low speed at that time indicated that the most probable scenario was an aerodynamic stall and subsequent right wing drop, consistent with an incipient spin. The height of the aircraft at that time was insufficient for the pilot to regain control before impacting the ground.

Weight and balance

Although the aircraft was being operated above its maximum take-off weight by about 102 kg at take‑off, and by about 39 kg at the time the pilot jettisoned the load, there was no evidence of an in-flight structural failure. There was insufficient evidence to determine what, if any, effect the overweight operation of the aircraft had on the flight characteristics or the development of the accident. Despite the overweight operation not being found to be contributory, operators and pilots are reminded that operations within the approved weight and balance envelop provide for known handling and performance characteristics.

Carburettor icing

The recorded temperature at about the time of the accident was 12.3 °C, with a dewpoint[5] of 10 °C. Given these temperatures, the probability of carburettor icing was calculated to be in the serious icing range at any power setting (see the Carburettor icing-probability chart that is available from the Civil Aviation Safety Authority website.

Increased humidity increases the likelihood of carburettor icing. If ice continues to accumulate in the carburettor, the flow of air to the engine reduces. If the process is allowed to continue, it will result in a power reduction, and eventually the engine will stop. Examination of the wreckage indicated that the engine was still operating, however, the level of power being produced was not able to be determined.

A carburettor heat control was available in NLP. If selected, warm air was directed from a heat muff[6] installed on the exhaust system to the carburettor inlet, melting any ice in the carburettor. Due to the level of damage, the ATSB could not determine the position of the carburettor heat control at the time of the accident.

As previously discussed, given the time between the accident and examination of the wreckage, there was insufficient evidence to conclude that carburettor icing occurred or affected normal engine operation.

__________

- Dewpoint: the temperature at which water vapour in the air starts to condense as the air cools. It is used, among other things, to monitor the risk of aircraft carburettor icing or the likelihood of fog.

- Heat muff: a heat exchanger wrapped around an exhaust system. It is usually used to supply warm air to the carburettor and provide cabin heat.

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the collision with terrain involving Piper Aircraft Corporation PA-25/A9 Pawnee, registered VH-NLP, which occurred 10 km west of Darlington, Victoria, on 20 March 2015. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

Contributing factors

- While positioning the aeroplane for a baiting run, and for reasons that could not be determined, the pilot inadvertently descended below the normal application height over an adjacent paddock before climbing and then losing control.

- The aircraft probably stalled and entered an incipient spin at a height from which the pilot was unable to regain control before colliding with terrain.

Other factors that increased risk

- The pilot took off with the aircraft about 102 kg over its approved maximum take-off weight, which can affect the aircraft’s handling characteristics.

Other findings

- The weather at the time of the accident was conducive to carburettor icing, but the time between the accident and examination of the wreckage meant that any ice, if present, had melted.

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included the:

- operator of VH-NLP

- maintainer of VH-NLP

- pilot’s aerial agriculture flying instructor

- Bureau of Meteorology

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Supplemental Type Certificate holder.

Submissions

Under Part 4, Division 2 (Investigation Reports), Section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 (the Act), the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. Section 26 (1) (a) of the Act allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the pilot’s aerial agriculture flying instructor, the operator of VH-NLP, the Bureau of Meteorology and the Civil Aviation Safety Authority.

Submissions were received from the operator and the Civil Aviation Safety Authority. The submissions were reviewed and where considered appropriate, the text of the draft report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2017

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |