What happened

In October 2009, the operator of Essendon Airport (now Essendon Fields Airport) received an application from the Hume City Council (HCC) to construct a radio mast on top of the council office building at Broadmeadows, Victoria. The application was made under the Airports (Protection of Airspace) Regulations 1996 (APA Regulations) which was only applicable to leased, federally-owned airports, such as Essendon. The application identified that the building and existing masts had not been approved under the regulations. The regulations required any proposed construction that breached protected airspace around specific airports to be approved by the Secretary of the then Department of Infrastructure and Transport (Department). Protected airspace included airspace above a boundary defined by the Obstacle Limitation Surface (OLS). The Secretary was required to reject the application if the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) determined that the application would have an ‘unacceptable effect on safety’.

CASA’s initial response to the HCC application stated that the building and existing masts represented a hazard to aircraft and should be marked and lit, while the proposed radio mast represented a further hazard and, as such, would not be supported. The advice was considered inadequate by the Department, who instructed CASA that they required advice that either the application for the mast had an unacceptable effect on safety, or it did not. CASA subsequently determined that the application did not have an unacceptable effect on safety, and in addition, advised the Department of specific lighting and marking requirements to mitigate any risk presented by the mast. The Department approved the HCC application on 28 February 2011 conditional on appropriate marking and lighting being affixed to the radio mast and building. The ATSB has since been advised that the radio mast has been removed due to reasons unrelated to aviation safety.

What the ATSB found

The scope of this investigation was limited to the processes associated with protecting the airspace at leased, federally owned airports, and in particular the application of safety management principles as part of that process. The investigation used the HCC application for examining the APA Regulations processes, and as a result identified an issue specifically associated with that application. However, the investigation did not consider whether or not the aerial on the HCC building was unsafe.

The Airports Act 1996, which was administered by the Department, was the principal airspace safety protection mechanism associated with a leased, federally-owned airport’s OLS. The Australian Government had committed to using a safety management framework in the conduct of aviation safety oversight (that is, a systemic approach to ensuring safety risks to ongoing operations are mitigated or contained). In contrast, the conduct of safety oversight of an airport’s airspace under the Airports Act used a prescriptive approach (that is, the obstacle was either acceptable or unacceptable). This approach met the requirements of the Airports Act, but was not safety management-based. With respect to the assessment of the HCC application under the Airports Act, a safety management approach was not used.

What's been done as a result

The Department, now known as the Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities, has advised that it will confer with key stakeholders in the APA Regulations process regarding relevant risk management practices. The intent is to implement a more systematic approach to risk management, guided by the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy.

The Department has also identified the need to reform the current airspace protection regime based around the Airports Act. In a paper titled ‘Modernising Airspace Protection’, the Department identifies that current airspace protection regulation under the Civil Aviation Act 1988 and the Airports Act requires improvement, and has initiated public consultation regarding reforms into this particular regulatory system.

Safety message

A safety management system approach is considered ‘best practice’ by the International Civil Aviation Organization and has been adopted by Australia as the core method of aviation safety oversight through the State Aviation Safety Program. The Airports Act processes need to adopt safety management principles to the assessment of construction applications involving breaches of prescribed airspace, but rather, used a prescriptive regulatory approach. Construction proposals can impinge on aviation safety margins, such as those represented by the OLS. A fully informed, safety management-based approach should be used to ensure that safety is not compromised.

The obstacle limitation surfaces

An airport is designed for a particular purpose. That purpose defines the type of operations envisaged at that airport and therefore the specific requirements for the airport’s construction. Other factors, such as the local geography and meteorological conditions, also affect the specifics of an airport’s design. These various factors determine the runway(s) dimension, which allow for particular types of approaches to and departures from the runway(s).

While natural features are considered in the initial design of an airport, man-made constructions, both inside and outside of the airport boundary, can significantly influence airport operations. The penetration of the airspace around the airport by man-made constructions may:

- result in limitations on the distances available for take-off and landing

- result in limitations on the range of meteorological conditions in which take-off and landing can be undertaken

- affect the minimum safe altitudes for instrument procedures to and from an airport

- represent a danger to aircraft operating at the airport during visual operations.

The airspace around an airport therefore forms an integral component of the airport, affecting not only the airport’s economic viability but also the safety of operations at that airport.[3]

International standards for civil aviation for the planning for, and operations of airports, are contained in the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Annex 14. Annex 14 includes standards and recommended practices that state that new objects or extensions of existing objects are not to be permitted within airspace above Obstacle Limitation Surfaces (OLS). An exception is when an ‘…aeronautical study … determined that the object would not adversely affect the safety…of aeroplanes.’ More details on the specific requirements of Annex 14 are provided in Appendix A: The Annex 14 OLS.

Legislative approach to protecting an Australian airports’ airspace

Australia utilises both a national consultative scheme as well as legislation in protecting an airport’s airspace. However, the consultative approach[4] is not relevant to this investigation as the HCC application fell within the jurisdiction of the Airports Act 1996.

The HCC application was made under the APA Regulations, a set of regulations that support the Airports Act. The Department was the agency responsible for the administration of this act and the APA Regulations.

The Airports Act 1996

The Airports Act created a comprehensive framework for the regulation of leased, federally owned airports, and other airports as listed in the Airports Regulations 1997. Part 12 of the Airports Act provided for the protection of airspace around these airports through the declaration of certain airspace to be prescribed airspace, and particular activities that affect that airspace to be controlled activities. These specific terms were defined as follows:

- Prescribed airspace. Airspace that was to be protected where it was in the interests of the safety, efficiency or regularity of existing or future air transport operations.

- Controlled activities. Activities that intruded into, or were planned to intrude into, prescribed airspace—such as the construction of a building or a structure on top of that building.

At the time of the HCC application, the airports that fell within the jurisdiction of Part 12[5] included Essendon Airport.

Part 12 required approval before carrying out a controlled activity. The process for obtaining that approval was governed by the APA Regulations.

In addition, s. 190 of the Airports Act stated that Part 12 operated in addition to, and not instead of, regulations made under the Civil Aviation Act (see Appendix B: Civil Aviation legislation and regulations).

Airports (Protection of Airspace) Regulations 1996

The Airports Act required approval for the conduct of controlled activities. The APA Regulations established the system under which an application to conduct controlled activities was assessed and either approved or rejected. These regulations also identified what type of airspace was included under the definition of prescribed airspace. Prescribed airspace included airspace as defined by the OLS, with Annex 14 cited as the source of the OLS dimensions, and what are termed PANS-OPS surfaces.[6]

The APA Regulations required that an application to conduct controlled activities be forwarded to the airport operator. The operator was required to notify the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA), Airservices Australia (Airservices) and the building authority of that application.

The decision on an application to conduct controlled activities was assigned to the Secretary of the Department (Secretary). In assessing a proposal, the Secretary was required to consider the opinions of the proponent of the activity (the applicant), the airport operator, CASA, Airservices and the building authority, but only with respect to the efficiency and regularity of air transport operations at the airport. The Secretary could also consider any other matter considered relevant. The decision process required the Secretary to approve a proposal unless carrying out the controlled activity interfered with the safety, efficiency or regularity of existing or future air transport operations into or out of the airport concerned. There were also two triggers that required the rejection of a proposal:

- the proposal entailed a long term controlled activity that penetrated PANS-OPS surfaces

- when CASA advised the Secretary that the proposed controlled activity would have an unacceptable effect on the safety of air transport operations.

Separately, CASA had the capacity under the APA Regulations to:

- advise the Secretary that a proposal had an ‘unacceptable effect on aviation safety’ and, on receipt of that advice, the Secretary was required to reject the proposal (the safety veto)

- provide a submission about the activity.

Safety management principles

Around 2006, ICAO required that States establish a State Safety Programme, which included the safety management method of conducting aviation safety oversight. In 2011, the Department published Australia’s State Aviation Safety Program (SASP). The SASP committed Australia to adopting the ICAO approach of using safety management principles in the oversight of aviation safety. A key component of this approach was the adoption of a risk-based approach to the management of aviation safety.

The Australian SASP identified specific legislation, regulations and other material that were relevant to the oversight of safety in aviation. That legislation included the Civil Aviation Act 1988, and a number of supporting regulations and manuals. Of note, the Airports Act and its supporting APA Regulations were not included within that legislation.

The APA Regulations application process

The role of the airport operator

The airport operator was responsible for gathering all relevant information concerning the application. This information included submissions from CASA, Airservices and the building authority, as well as any opinions on the effect that the controlled activity will have with respect to the efficiency and regularity of air transport operations into and out of the airport, existing and in the future. Once all relevant information, submissions and opinions were gathered, they were forwarded on to the Department, with the application for determination.

The role of CASA

CASA was responsible for the safety assessment of a proposal. It was reported that, when notified of an application under the APA Regulations, CASA commenced their safety determination by making a Civil Aviation Safety Regulation (CASR) Part 139 hazard assessment with respect to the application.[7] That assessment also included an analysis of whether the application affected the PANS-OPS surfaces, which was guided by advice provided from Airservices. CASA would recommend an application be rejected (or ‘vetoed’) if the assessment concluded that it would have an unacceptable effect on aviation safety, or if the PANS-OPS surfaces were affected.

CASA advised that:

- They did not seek input from the airport operator or relevant aircraft operators when making their safety assessment, as they understood that these matters would be addressed by other stakeholders in the application process.

- While they may be given safety data from other parties as part of the application package, their safety advice was produced using internal advice supplemented by advice from Airservices.

- On completion of the internal assessment of the application, the resultant advice to the Department was compiled using a standard template form to ensure that all required considerations, as identified by the Department, were addressed in their safety advice.

CASA also advised that it did not support any infringement of the OLS. In assessing prescribed airspace intrusions, CASA would determine that the proposal was either:

- acceptable without mitigation

- acceptable with mitigation such as lighting, marking or operational restrictions

- unacceptable.

The role of the Department

The Department administered and conducted the decision-making process under the APA Regulations. The Department published its policies and procedures regarding applications for controlled activities in prescribed airspace on its website. These policies and procedures reflected the content and requirements of the APA Regulations. The Secretary was required to approve a proposal, except in circumstances which included the following:

The carrying out of the controlled activity would interfere with the safety of existing or future air transport operations into or out of the airport.

CASA has advised the Secretary that the carrying out of the controlled activity would have an unacceptable effect on the safety and efficiency of existing or future air transport operations into and out of the airport.

The Department stated that it did not have the expertise to determine the safety effect of an application under the APA Regulations, and relied on advice from CASA for that purpose. The Department internally determined that CASA could not reject an application based on risk or hazard identification alone, and that CASA must either declare a proposal to be ‘unacceptable to safety’ or ‘not unacceptable to safety’. If the proposal was unacceptable to safety, then specific evidence identifying the reasons for that determination was required. If the proposal was not unacceptable to safety, then CASA was required to advise of any specific requirements that were to be attached to an approval.

The Hume City Council application

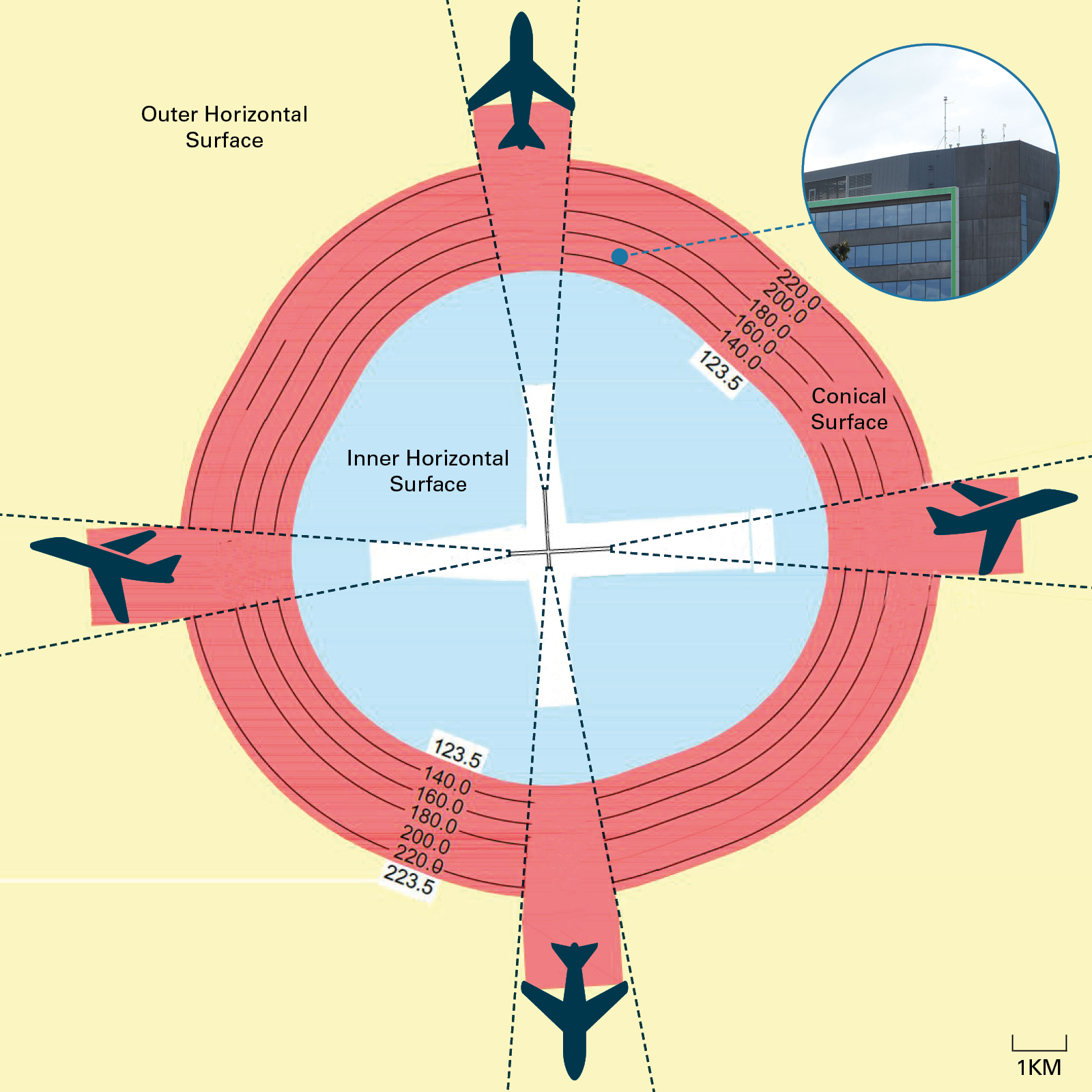

In preparation for the application for approval to construct the proposed radio mast on top of the existing HCC building, the council conducted a survey of the building. The HCC building is located 4.52 km (2.44 NM) on a bearing of 031° magnetic from the threshold of runway 17 at Essendon Airport. In respect of the OLS, the building is located between the 140 m (459 ft) and 150 m (492 ft) reduced levels (RL) of the OLS conical surface (Figure 2).[8] That survey identified that the building and two existing antennas on top of the building penetrated the Essendon Airport protected airspace, and in particular the conical surface of the Essendon OLS. The council also identified that the building and the existing antennas had not been granted approval under the APA Regulations when constructed. As a result, the HCC application included the proposed radio mast as well as the existing building and antennas.

Figure 2: Simplified depiction of the Essendon Airport OLS showing the location of the Hume City Council building.

Source: Essendon Fields Airport, modified by the ATSB. The contours and levels are reduced levels in metres to the Australian Height Datum. The aerodrome reference point is near the runway intersection, and is at about 78 m RL.

In accordance with the APA Regulations, in early October 2009 the Hume City Council (HCC) notified Essendon Airport of the proposed construction of the new radio mast. The airport operator notified the Department, CASA and Airservices of the HCC application. The notification also identified the issue of the existing building and antennas. The airport operator also advised CASA that the building and existing antennas were not fitted with obstacle marking or lighting. Additional survey data was submitted by the council in support of the application in June and July 2010, which was subsequently passed onto CASA and Airservices.

CASA and Airservices submissions

CASA’s evaluation of the proposal to construct the mast focused on how the existing building and antennas, as well as the proposed mast, individually interacted with the OLS and the PANS-OPS surfaces. CASA waited for the Airservices assessment of the impact of the application on the PANS-OPS surfaces before finalising its own assessment.

CASA’s preliminary evaluation identified that the building and proposed radio mast came close to, but did not breach, the Category B[9] visual manoeuvring (circling) areas[10] around Essendon Airport.

On 20 August 2010, Airservices advised the airport operator that the proposed radio mast would not ‘affect any sector or circling altitude, nor any approach or departure at Essendon or Melbourne airports’. Airservices also advised that the radio mast would not impact navigation aids, communications services or any other service associated with air navigation. Airservices also advised CASA of this assessment.

While three CASA Flying Operations Inspectors assessed the HCC application, the process applied by CASA did not include safety management principles in that assessment. This was evidenced by the fact that there was no indication of the level of residual risk deemed to be unacceptable from a safety perspective.

On 2 September 2010, CASA advised the airport operator that the building’s intrusion into the OLS represented a hazard to aviation safety, as defined by CASR Part 139 r. 139.370, due to its proximity to the Category B circling area at Essendon Airport. CASA recommended that the building be marked and lit in accordance with the Part 139 Manual of Standards (MOS). The advice also stated that CASA did not support the addition of any antennas and/or masts on the building due to the resulting further penetration of the OLS. However, CASA recommended that, should the Department approve the radio mast, it should be marked and lit in accordance with the MOS.

Essendon Airport submission

Based on the airport operator’s understanding that the HCC application required three separate decisions by the Secretary, the Essendon Airport submission was divided into the following three parts:

The building. With respect to the building itself, the airport operator raised a number of matters to support their recommendation that the building be marked and lit in accordance with the MOS. First, it was noted that the purpose of the OLS was to provide manoeuvring room for landing and departing aircraft. In addition, the airport operator stated that:

The proposed application [for the building] is located in the direction that an aircraft with an engine out [loss of engine power] on a northerly departure may elect to travel (to provide climb time) due to the presence of Melbourne International Airport to the west of the proposal and the hill upon which the suburb of Glenroy is built (located to the north east of Essendon Airport).

Finally, the airport operator identified that the building was just below the Category A and B visual manoeuvring (circling) areas for aircraft operations.

Existing antennas. In respect of the existing antennas atop the building, the airport operator stated that these increased the risk of collision and that the airport operator did not support their approval.

Proposed radio mast. The airport operator considered that the proposed radio mast further increased the risk of collision and for that reason did not support that application.

If the building was approved by the Department, the airport operator supported CASA’s view that it should be marked and lit in accordance with CASR r. 139.370. A number of other conditions on the Department’s approval of the building were proposed by the airport operator.

Department response to the combined submission

As required under APA Regulations r. 11, Essendon Airport submitted the HCC application to the Secretary for decision, along with the submissions from Airservices and CASA and their own submission regarding the application.

On 29 November 2010, the Department responded to the airport operator about the combined submission (copied to CASA). In its response, the Department stated that, notwithstanding the airport operator’s reasoning in respect of the existing antennas and the proposed radio mast:

Our legislation requires probative evidence that the risk is unequivocal. CASA has stated that all of the ancillary structures on top of the building are hazards and then goes on to offer a mitigating strategy by invoking MOS part 139 for each part. Unless CASA can definitively state that the antennae WILL result in increase of collision and remove the mitigating strategy then our only course is to recommend approval.

After discussions between the Department and CASA, CASA limited its submission on the building and proposed radio mast to a hazardous object assessment under CASR Part 139. CASA later provided further clarification to the airport operator on the marking and lighting requirements contained in its 2 September 2010 advice.

The Department’s correspondence with the airport operator of 29 November 2010 appears to have initiated discussion between the Department and the airport operator concerning the type of advice that should be provided within an APA Regulations submission. On 10 December 2010, the airport operator advised the Department that, under the current CASA submission, the Department was required to decide whether to either:

accept the risk associated with permitting the obstacles, which may be mitigated somewhat with lighting and marking

respond to the development through adjustment to the runway operations, such as shortening the runway to eliminate risk.

The airport operator also advised that if the Department approved the obstacles, the operator was, in any case, required to conduct a risk assessment on the obstacles in accordance with its safety management system.

The Department notified all relevant parties on 28 February 2011 of two decisions made under the APA Regulations concerning the HCC application. The decisions:

- approved the HCC application to construct the radio mast

- provided retrospective approval for the existing building and antennas.

The approvals were conditional on appropriate marking and lighting being affixed to the radio mast and building.

Summary of the application decision

The Essendon Airport submission to the Department included advice of a specific hazard (engine out after take-off scenario) believed to provide grounds for refusal of the HCC building application. The Department’s guidance concerning the structure of a safety opinion by CASA, as well as the Department’s practice of weighting its consideration of safety advice primarily towards that provided by CASA, appeared to influence the Department’s decision to overlook the hazard identified by the airport operator.

In this case, CASA officers considered the safety implications of a circling approach which was a lower safety risk than posed by the collision risk of the building and masts following an engine out after take-off scenario (as considered by the airport operator). However, CASA did not consult with the airport operator as it was assumed that the airport operator’s submission would be considered by the Department. In addition, the information on this hazard was not referred to CASA by the Department for consideration as part of its safety advice. As a result, CASA’s consideration of safety risks as part of the building application process was not fully informed.

The Department’s requirement for CASA to state that the controlled activity (antennae in this case) will result in an increased risk of collision as a means to reject an application set an expectation of unequivocal proof against which an assessment of any safety risk would be measured.

__________

- See ICAO Document (Doc) 9137 Airport Services Manual – Part 6 Control of Obstacles, Chapter 1 paragraphs 1.1.1 to 1.1.3.

- The National Airports Safeguarding Framework (NASF) is a Federal and State supported consultative framework for raising the awareness of local governments to specific planning and development issues for airports. In particular, Guideline F of the NASF identified an airport’s protected airspace as a necessary consideration when planning developments around an airport.

- See s. 180. These airports were either core regulated airports, as defined by s. 7 of the act, airports specified in the Airports Regulations that were a Commonwealth place, which in turn was defined at s. 5 of the act, or airports specified in the Airports Regulations that were not a Commonwealth place. The applicable airports were Sydney (Kingsford Smith), Sydney West, Bankstown, Camden, Melbourne (Tullamarine), Essendon, Moorabbin, Brisbane, Gold Coast, Archerfield, Townsville, Mount Isa, Perth, Jandakot, Adelaide, Parafield, Hobart, Launceston, Darwin, Tennant Creek, Alice Springs, and Canberra.

- Procedures for air navigation services (PANS) are ICAO documents that comprise operating practices that should be applied on a world-wide basis, but are too detailed for inclusion within the Annexes. PANS often amplify basic principles promulgated in the Annexes. There are a number of PANS publications, including Operations (PANS-OPS), Air Traffic Management (PANS-ATM) and Training (PANS-TRG). PANS-OPS includes the design and obstacle clearance requirements for specific flight procedures, such as instrument approach procedures and instrument departure procedures. The PANS-OPS surfaces are defined under PANS-OPS (Doc 8168) Volume II – Construction of Visual and Instrument Flight Procedures.

- This was the same assessment CASA would conduct when a hazard had been identified and notified to CASA by an airport operator.

- The RL represents the relative height of a point or object in relation to a specified datum, which for the Essendon Airport OLS was sea level. Therefore, all points or objects that lie on the 140 m RL are 140 m above sea level.

- Instrument approach procedure minimums use a grouping of aircraft based on a reference speed for landing. The Category B grouping is for aircraft with a reference landing speed of 91 kt or more but less than 121 kt,

- The area required for visual manoeuvring or circling after an instrument approach that brings the aircraft into position for landing on a runway which is not suitably located for straight-in approach or where the criteria for alignment or descent gradient cannot be met.

On 28 February 2010, the (then) Department of Infrastructure and Transport (Department) issued two decisions in response to a building application from the Hume City Council (HCC). The decisions, issued under the Airports (Protection of Airspace) Regulations 1996 (APA Regulations), granted approval for the:

- existing HCC building and associated antennas to breach the Essendon Airport protected airspace

- construction of an additional radio mast on top of the building that would further impact that protected airspace.

The HCC application concerned man-made construction that penetrated the Obstacle Limitation Surfaces (OLS). The APA Regulations required approval be given for particular activities which intruded, or were planned to intrude, into prescribed airspace. Prescribed airspace included the airspace above any part of an OLS (as defined by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Annex 14).

Prescriptive application approach

The Airports Act 1996, which was administered by the Department, was the principal method of facilitating the airspace safety protection mechanism associated with a federally-owned leased airport’s OLS. The APA Regulations enabled the Secretary of the Department to prevent the penetration of the OLS on grounds that included safety, meeting the intent of Annex 14.[11]

Examination of the approval process identified the following:

- The process did not include a requirement for safety management principles to be applied in determining the effect of a proposal on the safety of aviation.

- Department officials stated that the Department did not have the necessary expertise or resources to make a safety assessment and therefore was reliant on advice from CASA.

- The Department weighted CASA’s opinion regarding the safety of a proposal above all other submissions.

- While CASA was a recipient of the application, there was no process through which CASA would be provided with all relevant safety information before making their safety assessment.

The Department obtained internal legal guidance on how CASA’s advice and opinion should be constructed. The guidance indicated that CASA could not reject an application based on risk or hazard identification alone. For CASA to reject an application, it was required to state that the proposal was ‘unacceptable to safety’. CASA was also required to provide evidence as to the reasons for this decision. If the application was not unacceptable to safety, then CASA was required to identify any risk mitigating actions that would also need to take place. The Department notified CASA of the internal guidance.

The Department’s assessment process under the APA Regulations was prescriptive in nature in order to meet the regulatory requirements. The APA Regulations assessment process did not require a risk-based approach. However, the Airports Act and the APA Regulations were performing a safety function with respect to the protected airspace of a limited number of airports. A risk-based approach has been demonstrated as an effective approach to aviation safety risk management, and therefore should have been applied to the assessment of an application under the APA Regulations. Additionally, there was no guidance to CASA on the structure of their safety advice that could support a risk-based approach to the management of aviation safety. Further, the Department’s requirement for ‘probative evidence’ and a binary ‘unacceptable to safety or not’ decision did not align with the intent of ICAOs safety management system requirements regarding safety risk assessments.

In the ICAO advocated risk-based approach (also supported by CASA), the identification, assessment and treatment of risk is recognised as offering the best means to use all available information to manage risk. It does not rely on the demonstration of proof of a certain outcome before addressing underlying risk. As such, the approval process undertaken on the HCC application did not meet the safety management approach.

__________

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the building approval process for structures in the vicinity of Australian airports as applied to an application by the Hume City Council to construct a radio mast on their council building at Broadmeadows, Victoria. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

Safety issues, or system problems, are highlighted in bold to emphasise their importance. A safety issue is an event or condition that increases safety risk and (a) can reasonably be regarded as having the potential to adversely affect the safety of future operations, and (b) is a characteristic of an organisation or a system, rather than a characteristic of a specific individual, or characteristic of an operating environment at a specific point in time.

Contributing factors

- The Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities adopted a prescriptive approach to the Hume City Council building application within the obstacle limitation area of Essendon Airport, which was in accordance with the process prescribed under the Airports (Protection of Airspace) Regulations 1996, but did not require the application of risk management principles to the department’s consideration. [Safety Issue]

The safety issues identified during this investigation are listed in the Findings and Safety issues and actions sections of this report. The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) expects that all safety issues identified by the investigation should be addressed by the relevant organisation(s). In addressing those issues, the ATSB prefers to encourage relevant organisation(s) to proactively initiate safety action, rather than to issue formal safety recommendations or safety advisory notices.

All of the directly involved parties were provided with a draft report and invited to provide submissions. As part of that process, each organisation was asked to communicate what safety actions, if any, they had carried out or were planning to carry out in relation to each safety issue relevant to their organisation.

The initial public version of these safety issues and actions are repeated separately on the ATSB website to facilitate monitoring by interested parties. Where relevant the safety issues and actions will be updated on the ATSB website as information comes to hand.

The use of risk management principles when considering an application under the Airports (Protected Airspace) Regulations

Safety issue: AI-2013-102-SI-01

The Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities adopted a prescriptive approach to the Hume City Council building application within the obstacle limitation area of Essendon Airport, which was in accordance with the process prescribed under the Airports (Protection of Airspace) Regulations 1996, but did not require the application of risk management principles to the department’s consideration.

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included the:

- the Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities

- the Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Essendon Airport Pty Ltd

- Hume City Council

Submissions

Under Part 4, Division 2 (Investigation Reports), Section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 (the Act), the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. Section 26 (1) (a) of the Act allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities and the Civil Aviation Safety Authority.

Submissions were received from the Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities and the Civil Aviation Safety Authority. The submissions were reviewed and where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Appendix A: The Annex 14 OLS

International standards for civil aviation are published by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) in Annexes to the Chicago Convention. The planning for and operations of airports is contained in Annex 14. Annex 14 standards and recommended practices (SARPs) establish the Obstacle Limitation Surfaces (OLS) as a tool to ensure that an airport’s airspace is protected, for both economic and safety reasons.

At the time of the Hume City Council (HCC) application decision by the Department , the fifth edition of Annex 14 was in effect.[12] Included in Annex 14 was a section on Obstacle Restriction and Removal, which had the objective to:

… define the airspace around aerodromes to be maintained free from obstacles so as to permit the intended aeroplane operations at the aerodromes to be conducted safely and to prevent the aerodromes from becoming unusable by the growth of obstacles around the aerodromes. This is achieved by establishing a series of obstacle limitation surfaces that define the limits to which objects may project into the airspace.[13]

The Annex 14 definition of an obstacle was:

All fixed (whether temporary or permanent) and mobile objects, or parts thereof, that … extend above a defined surface intended to protect aircraft in flight …[14]

Over the various editions of Annex 14, the dimensions of the individual surfaces that make up the OLS have become more complex. In the fifth edition, the dimensions of the individual surfaces were based on the:

- intended runway use

- types of instrument approaches for that runway

- runway classification.

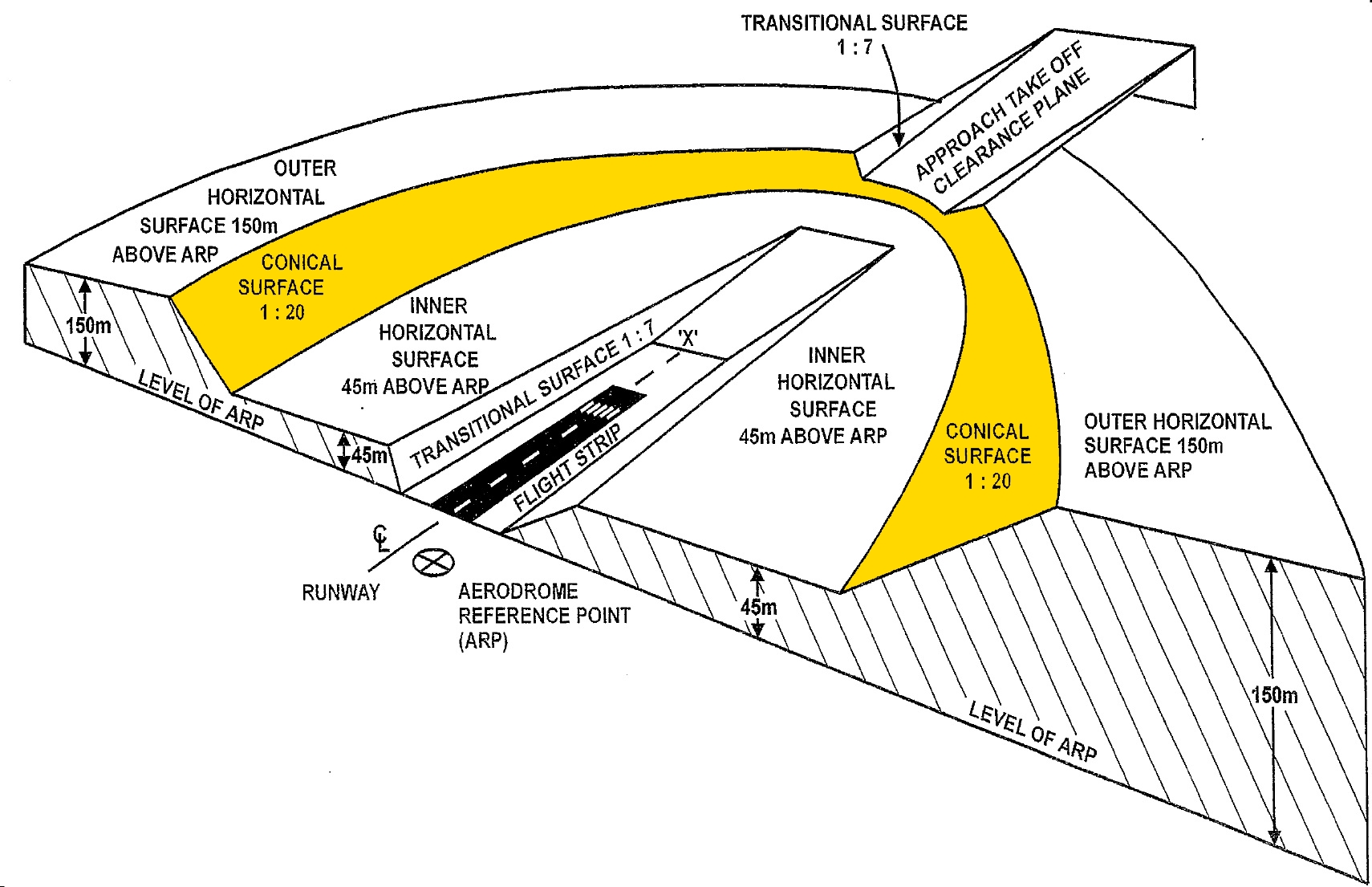

The final dimensions of the OLS were determined by the most stringent requirements relating to these criteria. The general structure of an OLS is shown in Figure 3.

Annex 14 includes standards that state that new objects or extensions of existing objects shall not be permitted above an approach, transitional or take-off climb surface. Annex 14 also includes recommended practices with respect to within the inner horizontal surface and the conical surface of the OLS (Figure 3). In respect to the conical surface, these recommended practices identified that:

New objects or extensions of existing objects should not be permitted above the conical surface … except when, in the opinion of the appropriate authority, the object would be shielded by an existing immovable object, or after aeronautical study it is determined that the object would not adversely affect the safety or significantly affect the regularity of operations of aeroplanes.

Implementation of the recommended practices required the capacity to prohibit objects that could or do penetrate the conical surface. The recommended prohibition against the penetration of the OLS included an important exception, that is when an ‘…aeronautical study … determined that the object would not adversely affect the safety…of aeroplanes.’ Guidance material associated with Annex 14 advocated that the OLS be made permanent through means such as legislation, or as part of a national planning consultation scheme.[15]

Figure 3: General structure of an OLS, with the conical surface highlighted in yellow.

Source: Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development, modified by the ATSB.

Appendix B: Civil Aviation legislation and regulations

The Civil Aviation Act 1988

While the HCC application was made under the Airports Act, Australia’s State Aviation Safety Program (SASP) identified CASA as being responsible for matters relating to Annex 14. CASA administers the Civil Aviation Act 1988 and supporting regulations. As noted in the body of the report, the Airports Act was not included in the SASP. The following sets out the regime under the Civil Aviation Act and Regulations related obstacles around an airport.

The Civil Aviation Act s. 3A stated that the main object of the act was to establish a regulatory framework for maintaining, enhancing and promoting the safety of civil aviation. The powers of the act to make regulations were prescribed in s. 98. Subsection 98 (3) identified specific areas where regulation could be made, which included:

(g) the prohibition of the construction of buildings, structures or objects, the restriction of the dimensions of buildings, structures or objects, and the removal in whole or in part or the marking or lighting of buildings, structures or objects, (including trees and other natural obstacles) that constitute or may constitute obstructions, hazards or potential hazards to aircraft flying in the vicinity of an aerodrome, and such other measures as are necessary to ensure the safety of aircraft using an aerodrome or flying in the vicinity of an aerodrome.

Relevant regulations that included the capacity to affect obstacles around an airport included the Civil Aviation (Building Control) Regulations 1988 (CABCR), the Civil Aviation Regulations (1988) (CAR) and the Civil Aviation Safety Regulations 1998 (CASR).

The Civil Aviation (Building Control) Regulations 1988

The CABCR provided a regulatory regime for the control of buildings around certain aerodromes. The aerodromes that fell within the jurisdiction of the CABCR were identified through relevant schedules and were limited to Sydney (Kingsford Smith), Bankstown, Melbourne, Moorabbin, Essendon and Adelaide.

The regulations required CASA’s approval for the construction of buildings or structures that exceeded certain heights above the ground. The regulations created three types of zones based on three height restrictions that were to be applied to specific land areas:

- a zone adjoining the aerodrome, in which approval was required for any construction above 25 ft above ground level (AGL)

- the next zone out, which required approval for any construction up to 50 ft AGL

- the zone furthest from the aerodrome, which required approval for any construction up to 150 ft AGL.

While still in force at the time of the occurrence, CASA advised that the CABCR were outdated and rarely, if ever, used. CASA also advised that the HCC building and proposed radio mast did not fall within the requirements of the CABCR.

The Civil Aviation Regulations 1988

Part 9 of the CAR, titled Aerodromes, contained regulations that enabled the protection of an aerodrome’s airspace. Under CAR r. 95 CASA could prevent, or direct the removal of, intrusions into a defined volume of airspace around an aerodrome.

Two limitations applied to the scope of r. 95:

- The first related to the aerodromes that fall within the regulation’s jurisdiction. This was defined under r. 95(1), which limited the affected aerodromes to those that are ‘open to public use by aircraft engaged in international air navigation or air navigation within a Territory’.[16] The sub-regulation also excluded aerodromes covered by the CABCR.

- The second concerned the dimensions of the airspace that was protected. This airspace, as defined under r. 95(5), equated to only a small subset of the possible dimensions of the OLS as promulgated in Annex 14.

The Civil Aviation Safety Regulations 1998

Part 139 of the CASR dealt with the operation of aerodromes. Subpart 139.E was concerned with obstacles and hazards in airspace around an aerodrome. These regulations required the aerodrome operator to establish an OLS in accordance with guidance in the Manual of Standards Part 139 – Aerodromes (MOS). The MOS reproduced the method of constructing the OLS as stated in Annex 14.

Subpart 139.E required an aerodrome operator to monitor the airspace around their aerodrome. If an obstacle was identified, or a proposed construction was likely to become an obstacle, then the operator was required to notify:

- the relevant authorities

- pilots, by issuing a notice to airmen (NOTAM).[17]

Subpart 139.E also enabled CASA to determine that certain obstacles were hazards due to their location, height or lack of marking or lighting. If an object was determined to be a hazard, CASA was able to request the obstacle’s owner to mark and/or light the obstacle.[18] Specific requirements for obstacle lighting and marking were contained in the MOS.

Finally, CASR r. 139.035 stated that nothing in Part 139 affected the operation of the Airports (Protection of Airspace) Regulations 1996.

The Part 139 regulatory framework did not contain any provision for preventing the construction of, or removing existing, objects deemed to be a hazard. Should a runway become unsafe as a result of an obstacle, CASA advised that it would enforce CAR r. 92. That regulation made it an offence:

- for an aircraft to take-off or land from a place where this cannot be done with safety, or

- to contravene a CASA direction relating to the safety of air navigation for that aerodrome.

__________

- The fifth edition was dated July 2009. A further edition, the sixth edition, came into effect in June 2013, while the current edition is the seventh dated July 2016.

- Annex 14 Chapter 4 Note 1.

- Annex 14 Chapter 1.

- ICAO Document 9137 Airport Services Manual.

- The Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP)GEN 1.2 section 2 titled Designated International Airports identified international airports. Airports that fall within the Major category are Adelaide, Brisbane, Cairns, Darwin, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney. Airports that fall within the Restricted Use category, being airports where entry and departure is permitted with prior approval only, are Avalon, Broome, Canberra, Coffs Harbour, Gold Coast, Hobart, Learmonth, Lord Howe Island, Port Hedland, Townsville and Williamtown/Newcastle.

- A NOTAM advises personnel concerned with flight operations of information concerning the establishment, condition or change in any aeronautical facility, service, procedure, or hazard, the timely knowledge of which is essential to safe flight.

- CASR r. 139.370(4)(a)(ii) also requires the notice to be given to ‘the authority, or, if applicable, one or more authorities whose approval is required for the construction…’

On 28 February 2011 the (then) Department of Infrastructure and Transport (Department)[1] issued two decisions regarding an application by the Hume City Council (HCC) to construct a radio mast on top of the council office building at 1079 Pascoe Vale Road, Broadmeadows, Victoria (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Hume City Council building showing the existing antennas (circled in red) and the (then) proposed radio mast (indicated with a blue arrow).

Source: ATSB.

The application was made under the Airports (Protection of Airspace) Regulations 1996 (Cwth) (APA Regulations). The APA Regulations required any proposed construction that breached protected airspace around specific airports, referred to as controlled activities, to be approved by the Secretary of the Department (the Secretary). Protected airspace included airspace as defined by the airport’s obstacle limitation surfaces (OLS), which were in turn defined within Annex 14 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation.

In September 2012 the ATSB received a REPCON[2] report concerning the HCC application. The reporter expressed concern that a proper safety case was not conducted on the HCC radio mast proposal, and that the location of the antennas had implications for aviation safety. The ATSB notified the Civil Aviation Safety Authority, the airport operator and the Department of the REPCON report, and liaised with the affected parties during its initial examination of the approval process for structures that penetrate the OLS. That examination identified a possible underlying transport safety matter in respect of the approval process in this case and, in July 2013, the ATSB commenced an investigation under the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003.

The scope of the investigation was limited to the processes associated with protecting airspace at leased, federally owned airports—that is, airports covered by the APA Regulations—and in particular the application of safety management principles, established by the International Civil Aviation Organization and adopted by Australia, as part of that process. The investigation used the HCC application for examining the APA Regulations processes. The investigation did not consider whether or not the proposed aerial on the HCC building, or the building and associated attached structures, were unsafe.

__________

- From October 2010 to September 2013 the now Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities was known as the Department of Infrastructure and Transport. The Department was also known by other names in the interim. The Department administers the Airports Act 1996 and all subordinate regulations.

- REPCON is a voluntary and confidential reporting scheme that is established under the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 (Cwth). It allows any person with a safety concern to report it to the ATSB confidentially. Protection of the reporter's identity and any individual referred to in the report is a primary element of the scheme.