Investigation summary

What happened

In early May 2022, heavy rain fell across catchments of the Brisbane River. In response, the region’s water management agency performed several controlled water releases from dams located upriver from the Port of Brisbane. The subsequent high freshwater inflows resulted in increased current speeds through the port, exposing ships to the risk of breaking free from their berths.

At 1313 local time on 16 May, the container ship OOCL Brisbane broke away from its berth at Fisherman Islands. All the ship’s mooring lines parted or paid out shortly after another ship, Delos Wave, passed OOCL Brisbane in the adjacent channel and berthed immediately ahead of it.

At 0636 on 20 May, the container ship CMA CGM Bellini was working cargo alongside a berth at Fisherman Islands when 2 of its forward mooring lines parted and its bow drifted off the wharf. This breakaway also occurred shortly after another ship, APL Scotland, passed and berthed ahead of CMA CGM Bellini.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that the cause of the breakaways was a combination of increased ebb current flows and additional interaction forces and water flow disturbances introduced by Delos Wave and APL Scotland. These combined factors resulted in hydrodynamic forces which exceeded the berthed ships’ mooring arrangement capacities.

The investigation identified that Maritime Safety Queensland (MSQ), the safety regulator, and the port’s pilotage provider, Poseidon Sea Pilots (PSP) did not have a process to jointly and effectively identify and risk assess the hazards to shipping and pilotage that were outside normal environmental conditions. As a result of this safety issue, MSQ and PSP did not identify and adequately address ship interaction as a hazard that increased the risk of a breakaway at Fisherman Islands.

What has been done as a result

Following the breakaway of the oil tanker CSC Friendship in February 2022 further upriver in the port (ATSB investigation MO‑2022‑003) and these breakaways at Fisherman Islands in May, MSQ has taken the safety action summarised below.

Between July and October 2022, MSQ commissioned several investigations and studies into the breakaways, which included analyses of mooring and river conditions, port operations and contingency planning arrangements.

Additionally, MSQ engaged with multiple port stakeholders, including PSP, terminal operators, the Australian Bureau of Meteorology and Seqwater to improve collaborative planning for, and response to, extreme weather events including river flood. Subsequently, MSQ has gradually amended its procedures for responding to extreme and adverse weather events. From late 2023, these procedures reflected the Queensland Government’s adoption of the Australian Warning System, which provides a nationally recognised set of warning levels and icons to communicate and manage dangers associated with extreme weather events.

In late 2024, MSQ established the Port of Brisbane Maritime Emergency Working Group (MEWG) and developed guidelines for the group’s role in responding to port emergencies, including severe weather, river flood and dam water releases. A stated function of the MEWG, which included representatives from MSQ, Port of Brisbane and PSP, was to facilitate timely and collective assessment of potential hazards to port safety posed by significant weather events and emergencies so that appropriate controls could be identified and implemented.

Capital improvements include the installation of 3 additional current meters in the river (with additional meters planned) and the provision of data from these meters to key stakeholders, including PSP.

In December 2024, PSP advised the ATSB that it had worked closely with MSQ since the 2022 breakaways to establish a formal channel for all port stakeholders to collaboratively identify and risk assess hazards to shipping outside of normal environmental conditions. During this time, PSP progressively updated its pilotage operations safety management system to provide detailed procedures for preparing and responding to severe weather events. These procedures were developed in collaboration with MSQ and consistent with guidelines for the MEWG.

Additionally, PSP provided input for changes to MSQ’s standard port procedures. This included the joint development of procedures for movements to and from various berths under flood conditions using MSQ’s bridge/ship simulator.

Safety message

The breakaway incidents highlight the importance of structured and clearly defined emergency and risk management arrangements for managing port shipping movements outside of normal operating conditions. Such arrangements must facilitate accurate assessment of all the available information by the involved parties and provide for adequate assessment of all potential risks.

The occurrences

Background

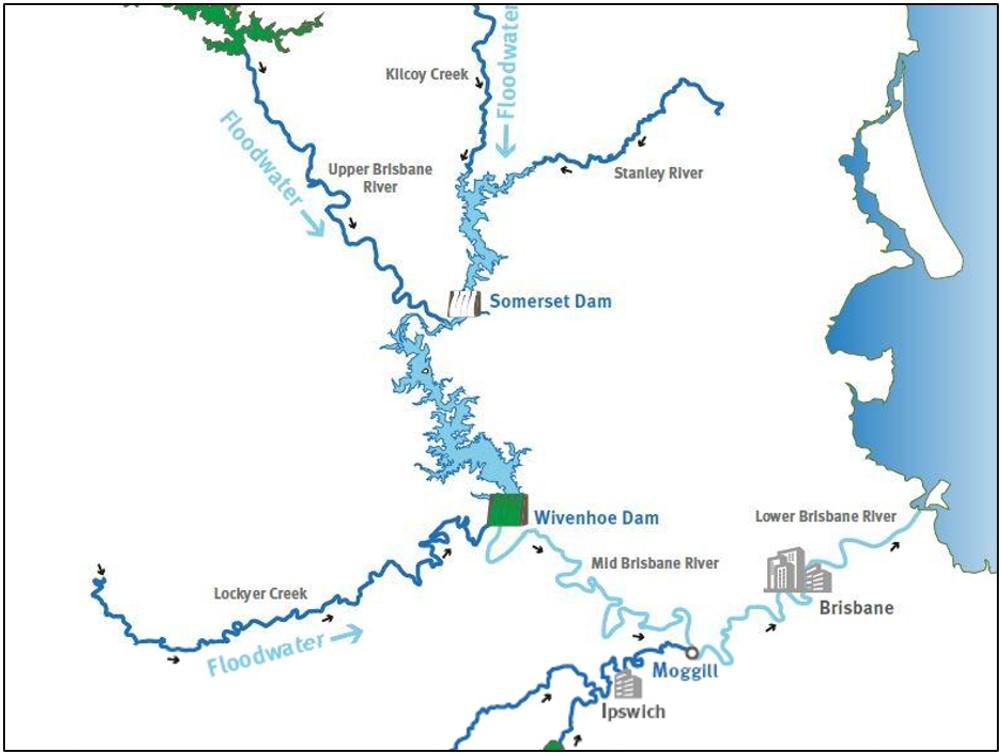

In February and March 2022, areas of south‑east Queensland experienced unprecedented rainfall, which resulted in a series of destructive flooding events across the region, including the catchments of the upper and lower Brisbane River (Figure 1). The conditions over this period led to abnormally high currents (peaking at about 5 knots) in the Brisbane River and resulting in the breakaway of the oil tanker CSC Friendship from its berth on 27 February 2022 (see the section titled Previous occurrences).

Figure 1: The Brisbane River

Source: Queensland Government, annotated by the ATSB

While rainfall across the region eased during April, on 6 May 2022 the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) released advice of forecast significant rainfall for the following week. Subsequently, with catchments across south-east Queensland still saturated from the rainfall in February and March, Seqwater[1], as part of its strategy to manage dam water levels, issued advice on that same day that it would commence low-flow operational releases from Wivenhoe and Somerset dams, located upriver of the port.

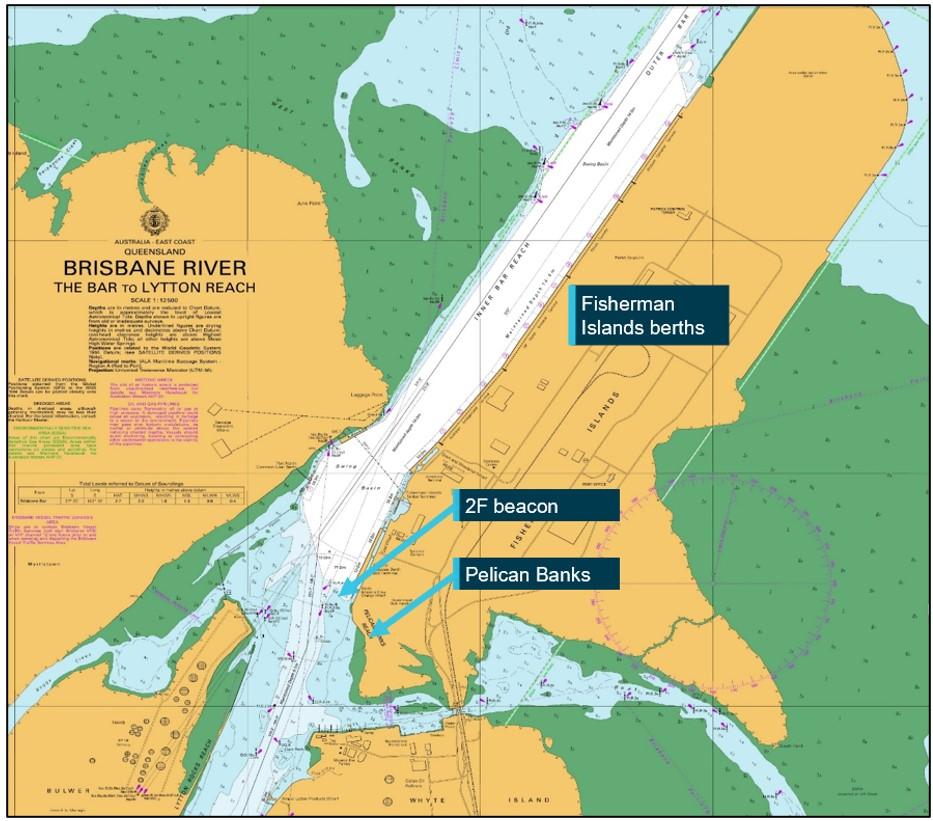

Later that day, following the Seqwater advice, Brisbane’s regional harbour master (RHM) directed the port’s vessel traffic service (VTS) to monitor river current meter readings against predicted flows every 2 hours and report any deviations. At the time, there was only one river current flow meter, located at the 2F beacon in Pelicans Banks Reach and immediately upriver of Fisherman Islands. (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Location of the 2F beacon current flow meter

Source: Australian Hydrographic Office, annotated by the ATSB

Additionally, the RHM directed VTS to notify port stakeholders, including terminal operators, ship masters (through the local agent) and the port’s pilotage provider, Poseidon Sea Pilots (PSP), of potential disruptions to ship movements in the coming days due to forecast rain and planned dam releases. Strong winds and rough seas and swell in the area of the pilot boarding ground (PBG) outside Moreton Bay at the port’s entrance were also expected to affect the pilot boat transfers. However, despite the predicted conditions, ship movements in and out of the port were able to proceed without disruptions over the following 3 days.

On 11 May 2022, BoM forecast more significant rainfall across the region. At 0715, Seqwater’s flood operations centre advised that it had moved to its ‘stand-up’ activation level and was increasing dam releases to mitigate the risk of flooding. At 1145, Seqwater further advised that releases from Wivenhoe Dam would exceed 1,000 m³ per second overnight. At 1245, BoM issued a moderate flood warning for the upper Brisbane River.

In response to Seqwater’s notification of increased dam releases, the RHM directed VTS to suspend all immobilisation[2] permits and advise ships’ agents to ensure berthed and arriving ships deployed additional mooring lines. Ships berthed upriver from Pelican Banks were required to be at immediate readiness to depart and further arrivals to those berths were suspended. While movements at Fisherman Islands berths were to continue, nighttime pilot transfers were suspended later that day due to heavy swell at the PBG.

On the morning of 12 May, BoM issued a minor flood warning for the lower Brisbane River, in addition to a series of major and moderate flood warnings for locations throughout the lower Brisbane River catchment. The RHM anticipated that flood waters from the lower catchment would result in stronger river current flows.

Later that day, the RHM advised PSP via email that BoM had prepared a flood scenario outlook which indicated the lower Brisbane River would most likely experience minor flood levels at high tide on 14 and 15 May. This outlook also indicated that it was possible that the minor flood level could be reached on 13 May and remain at that level until 16 May. The RHM advised VTS and PSP that dam releases were being varied to manage the flood levels and therefore, unless there was significant rainfall over the lower river catchment, they did not expect a significant change to the increase in river current flow, which was observed to be about half a knot faster than normal spring ebb flows. By 1430 on 12 May, the last remaining ship berthed upriver from Pelican Banks had evacuated the river under the direction of the RHM.

On 13 May, as rainfall over the lower Brisbane River catchments increased, releases from Wivenhoe Dam were temporarily stopped to allow peak inflows from catchments downstream of the dam to pass. Meanwhile, the maximum current flow recorded was 2.5 knots, about 1 knot faster than the normal predicted ebb (downriver) flow. With sea and swell conditions at the PBG continuing to disrupt pilot transfers, there were only a limited number of ship movements that day.

That afternoon, the VTS manager advised PSP management, terminal operators, ships’ agents and other port stakeholders of the planned movements on the following day. Scheduled movements at Fisherman Islands were to proceed with additional restrictions in place due to the increased river current. The precautions prohibited the berthing of ships more than 300 m in length, with all others required to be berthed head-up (facing upriver). Only daylight movements were permitted, and with a minimum of 2 tugs.

At 0300 on 14 May, releases from Wivenhoe Dam resumed. Meanwhile, sea conditions at the PBG had further deteriorated, preventing the resumption of pilot boat operations. Consequently, only a limited number of movements were conducted between Fisherman Islands and the inner anchorage, located within the relatively sheltered waters of Moreton Bay.

OOCL Brisbane breakaway

By 15 May, conditions at the PBG had eased while the maximum ebb flow observed at the current meter was 2.3 knots. The RHM decided that these conditions allowed for the resumption of scheduled movements to Fisherman Islands.

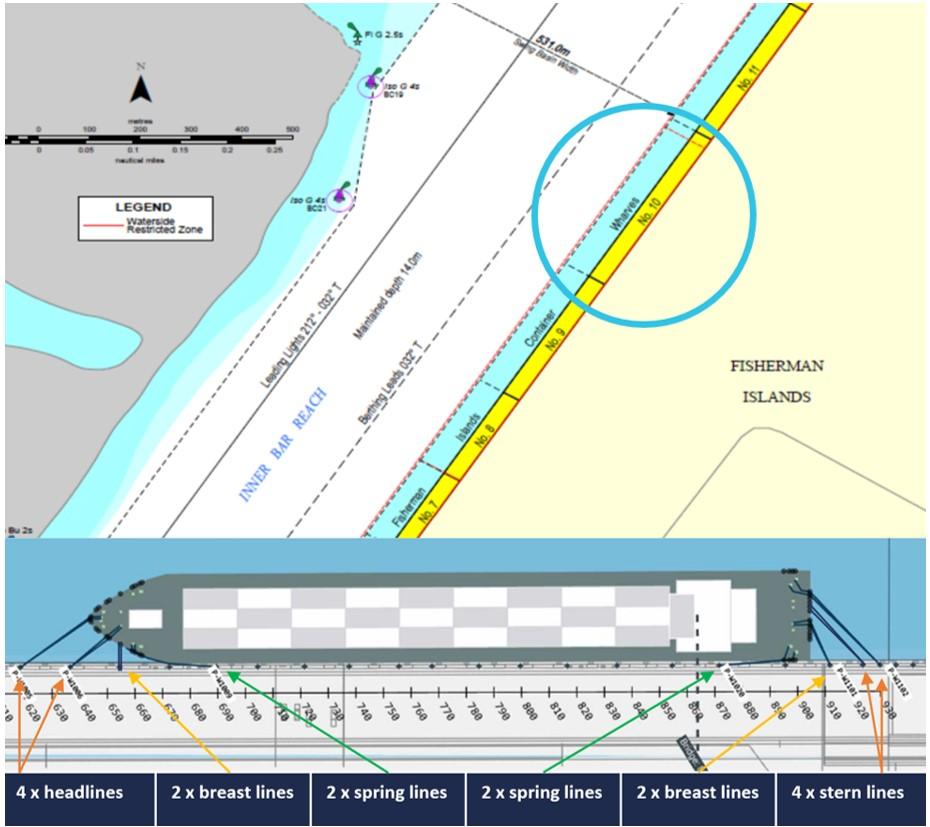

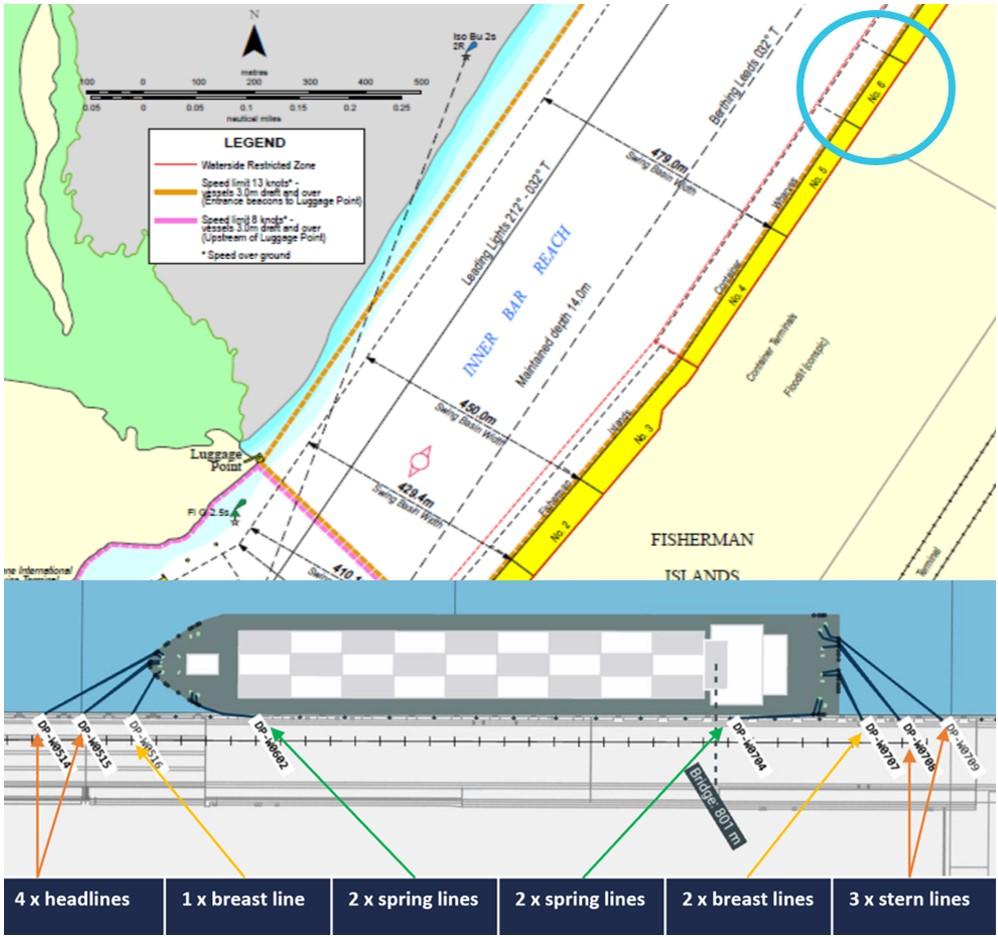

At 1058, a pilot boarded the container ship OOCL Brisbane at the PBG to conduct it to Fisherman Islands berth number 10. The pilotage proceeded normally and by 1725, the ship was berthed port side alongside (head-up) (Figure 3).

The ship was made fast with 16 polyamide mooring ropes – 4 head and stern lines, 2 breast lines fore and aft and 2 spring lines fore and aft, or 4-2-2 fore and aft. Of these 16 ropes, 12 were secured on their mooring winches held by a manual friction brake. The remaining 4 (both forward breast lines and 2 inboard stern lines) were turned up on bitts forward and aft. The ship’s outboard (starboard) anchor was lowered to the seabed as an additional precaution. The master ordered the moorings to be checked and tended every hour. Later that evening, cargo operations commenced.

Figure 3: OOCL Brisbane mooring arrangement

Source: Maritime Safety Queensland and Seaport OPX, annotated by the ATSB

By the morning of 16 May, disruptions over the previous week had resulted in about 40 ships being anchored off the port limits, awaiting entry to the port. The maximum current recorded by the meter during the previous ebb tide had peaked at 2 knots, about 0.8 knots higher than predicted. The RHM decided that about 10 ship movements scheduled that day could go ahead subject to existing restrictions.

At 0906, a pilot boarded the container ship Delos Wave, inbound to Fisherman Islands berth number 9, immediately upriver from OOCL Brisbane. At the time of the ship’s scheduled arrival alongside, the tide would be ebbing with high water (2.14 m) predicted for 0918 and low water (0.31 m) at 1537 (at the entrance to the Brisbane River). During the pilotage, VTS advised the pilot that the river current (ebb) was 2.2 knots. When the ship entered the river, the pilot estimated there to be an east-south‑easterly wind of about 7–10 knots.

At 1116, VTS emailed port stakeholders advising that it was planning to resume further scheduled movements over the following days, also indicating that it was likely that some of the restrictions would be lifted from 17 May.

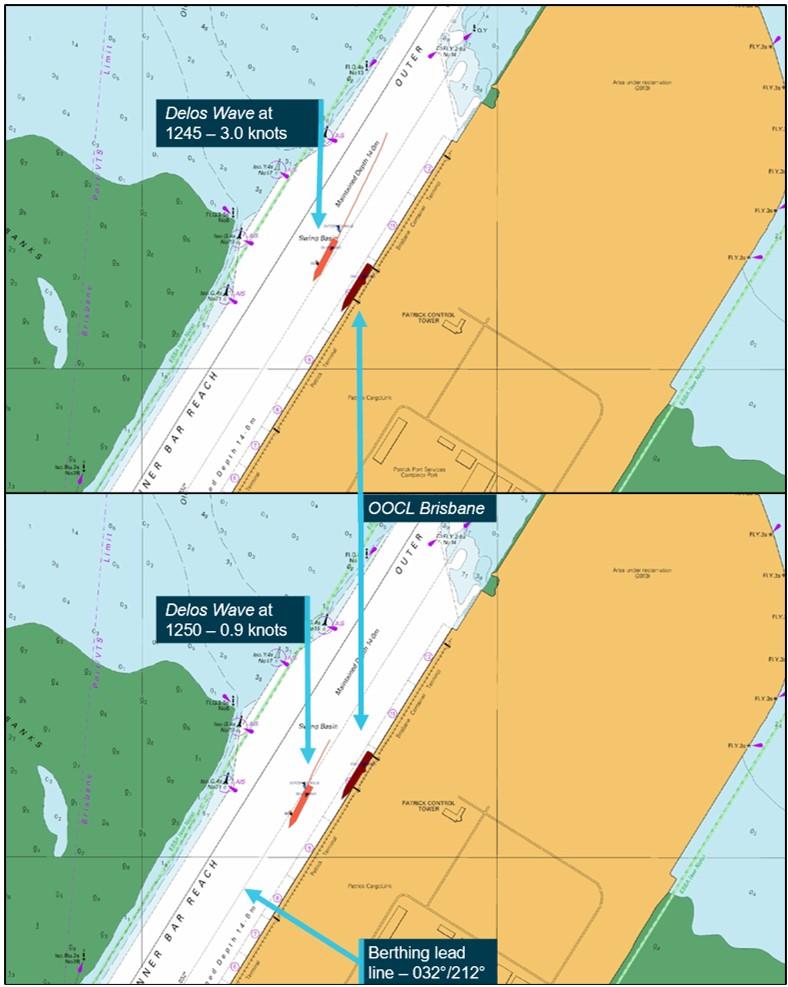

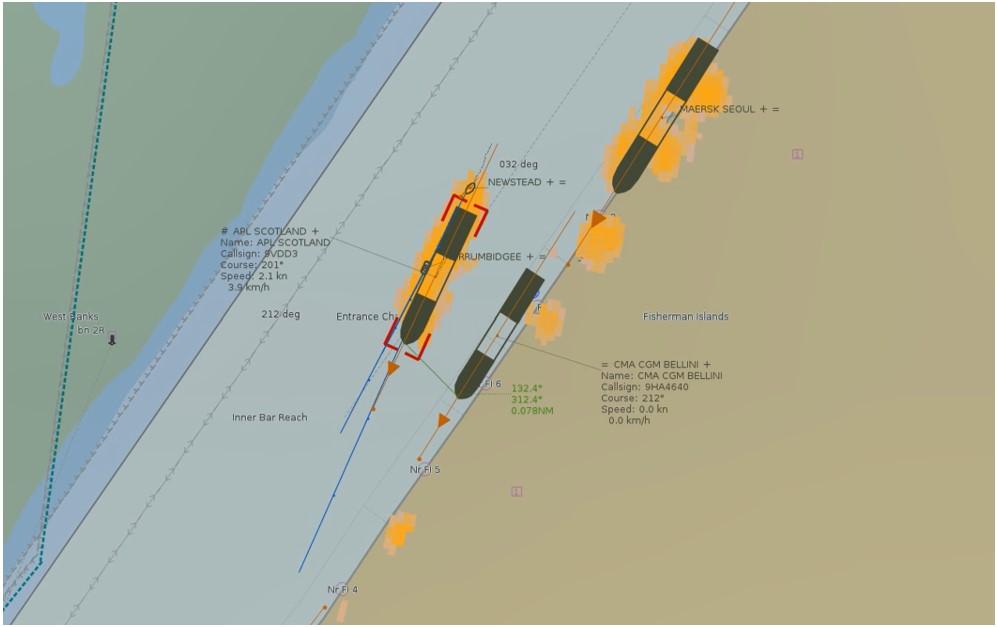

At 1239, Delos Wave was passing berth number 12 at a speed of 4.8 knots (over ground). The pilot planned to keep the ship close to the 212° (T) leading line for berthing that ran parallel to the Fisherman Islands wharf face (180 m from the face). The pilot had planned that by the time the ship was off berth number 9, its speed would have been reduced so it was stationary (over ground). The 2 tugs in attendance would then push it alongside the berth.

At 1245, Delos Wave was passing OOCL Brisbane at a distance of about 113 m at 3 knots (Figure 4, Top). Five minutes later, Delos Wave’s speed was 0.9 knots as its stern passed the bow of OOCL Brisbane. The distance between the ships was about 100 m.

Figure 4: Delos Wave passing OOCL Brisbane

Source: Australian Hydrographic Office and OOCL Brisbane’s voyage data recorder, annotated by the ATSB

After Delos Wave passed OOCL Brisbane, the pilot began manoeuvring the ship towards its berth. At 1254, when Delos Wave was about 40 m from the berth, its first mooring line was passed ashore with the pilot directing the tugs as required. The pilot was also using short bursts of dead slow ahead on the ship’s main engine to counteract the current and keep the ship stationary off the berth. Astern of the ship, OOCL Brisbane had begun to surge and yaw. At about this time, a duty crew member on OOCL Brisbane’s deck reported to the second mate that the bow was moving away from the berth. The second mate immediately notified the chief mate (via UHF radio) and then instructed the crew to standby the forward and aft moorings. Meanwhile, stevedores working cargo noticed the ship moving away from the wharf and soon after, all 3 cranes stopped working cargo and raised their booms clear.

When OOCL Brisbane’s master arrived on the bridge at 1258, its heading[3] was 218° (it had been 212° when alongside). One of its forward spring lines and both forward breast lines had parted and the remaining mooring lines forward had started to pay out.[4]

At 1259, the master ordered the engineers to standby the main engine and bow thruster for emergency use, and then notified VTS (via VHF radio). Shortly afterwards, VTS advised the master that a tug (not one of those attending Delos Wave) was en route to assist.

Meanwhile, the crew’s attempts to heave in the forward mooring lines had not succeeded and by 1303, the bow had swung about 15° away from the wharf. At 1304, the remaining forward spring line parted. Moments later, the master had the bow thruster at full port thrust. From 1307, the main engine was run (dead slow ahead and then half ahead) with the rudder hard to port to return the ship alongside. The ship, however, continued to move further away from the berth.

By 1308, all forward lines had parted or fully paid-out (Figure 5). All the aft mooring winches had also begun to pay out and the 2 inboard stern lines turned up on the bitts parted at about this time.

Figure 5: OOCL Brisbane breaking away (image shows the last headline parting)

Source: Maritime Safety Queensland

Meanwhile, Delos Wave had come alongside its berth and, by 1310, had one mooring line out at each end. Astern of it, OOCL Brisbane had broken away with its aft winches still paying out. The ship came close to the ship berthed astern of it before moving across to the other side of channel. By 1313, when the tug arrived to assist, all the ship’s aft mooring lines had parted or paid-out. One of the tugs attending Delos Wave was also released to assist OOCL Brisbane.

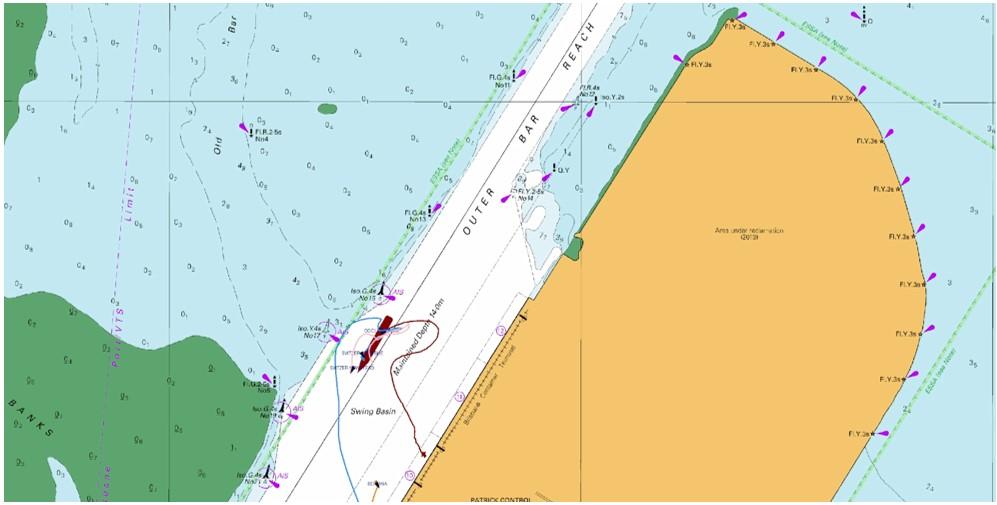

By 1323, OOCL Brisbane was near the opposite side of the channel with the 2 tugs assisting with controlling its movement (Figure 6). Shortly afterwards, the other tug attending Delos Wave was also released to assist OOCL Brisbane. The 3 tugs then aided OOCL Brisbane to remain within the channel while VTS arranged a pilot.

Figure 6: OOCL Brisbane at 1323

Source: Australian Hydrographic Office and OOCL Brisbane’s voyage data recorder, annotated by the ATSB

At 1357, the master let go the starboard anchor to maintain position while waiting for the pilot. After boarding at 1418, the pilot agreed a plan with the master to take the ship to an anchorage at Moreton Bay (the ship had no usable mooring ropes). At 1505, after weighing anchor, the pilot conducted the ship to the anchorage.

As all OOCL Brisbane’s mooring ropes had parted and several mooring winches were damaged, it remained at the anchorage for several days while new ropes and spare parts were supplied. The RHM also required an independent surveyor to conduct an investigation and inspect the mooring equipment (see section titled OOCL Brisbane - Mooring equipment).

On 26 May, a pilot conducted the ship back to the same berth where 6 of its cargo hatch covers had remained after the breakaway.

CMA CGM Bellini breakaway

Following the breakaway of OOCL Brisbane, MSQ continued to monitor river current conditions and reviewed ship mooring configurations using its NCOS[5] mooring tool, applying an assumed additional loading of 3 knots of current speed alongside the berths. Ship movements to and from Fisherman Islands berths continued, with existing restrictions still in place. Arrivals to berths upriver from Pelican Banks also resumed. On 18 May, the RHM decided that ships of more than 300 m in length could resume berthing at Fisherman Islands. While rainfall had eased, the continuation of controlled releases from Wivenhoe Dam was resulting in a greater ebb river current than during a normal spring ebb tide.

At 0836 on 19 May, the container ship CMA CGM Bellini berthed port side alongside (head‑up) at Fisherman Islands berth number 6 (Figure 7). The ship was made fast with 14 polyamide mooring ropes – 4 headlines, 3 stern lines, 1 forward breast line, 2 aft breast lines and 2 spring lines fore and aft. As an additional precaution, the starboard anchor was lowered to the seabed. Of the 7 forward ropes, 6 were secured on their mooring winches and held by a manual friction brake while the forward breast line was turned up on bitts.

Figure 7: CMA CGM Bellini mooring arrangement

Source: Maritime Safety Queensland and Seaport OPX, annotated by the ATSB

At 0236 the following day, a pilot boarded the container ship APL Scotland at the PBG. The ship was bound for Fisherman Islands berth number 5, immediately upriver from berth number 6 where CMA CGM Bellini was working cargo. During the master and pilot information exchange, the pilot informed the master that a strong ebb current and south-easterly winds could be expected at the berth and additional mooring ropes would be necessary.

At 0618, as APL Scotland entered the Brisbane River, a harbour tug attended the ship and made fast on its starboard quarter. At 0623, as the ship passed Fisherman Islands berth number 9 at a speed of 5 knots, another tug made fast on the ship’s starboard shoulder. The tide was ebbing, with the predicted high water (2.59 m) having occurred at 0028 and low water (0.61 m) predicted for 0725. At the time, the current meter recorded an ebb flow of 1.5 knots and the pilot recalled south-easterly winds of 16–19 knots.

At 0625, APL Scotland’s speed had slowed to 4.2 knots as its bow came into line with the stern of CMA CGM Bellini. At this time, the distance between the ships was about 160 m. By 0628, APL Scotland was 120 m off CMA CGM Bellini’s beam, at a slight angle to the 212° leading line for berthing and its speed had reduced to 2.1 knots (Figure 8).

Figure 8: APL Scotland passing CMA CGM Bellini at 0628

Source: Maritime Safety Queensland

At 0634, CMA CGM Bellini began to surge and yaw at its berth as APL Scotland’s stern passed about 80 m from its bow. At about the same time, APL Scotland’s pilot ordered its main engine slow astern for a brief period to reduce speed.

At 0635, as the pilot began manoeuvring APL Scotland towards the berth, one of CMA CGM Bellini’s inner headlines began to pay out. A duty crew member on deck saw the bow moving away from the berth and called the duty officer (the third mate) on the bridge (via UHF radio). The third mate alerted the chief mate via radio and then went forward. At 0636, the forward breast line partially parted, followed by the parting of one of its forwardmost headlines a few seconds later (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Headline parts at 0635

Source: Maritime Safety Queensland, annotated by the ATSB

By 0637, the ship’s bow had drifted about 8 m off the wharf face. On APL Scotland’s port bridge wing, the pilot had heard the headline parting and saw CMA CGM Bellini moving off the berth. The pilot alerted the shore mooring gang and asked the masters of the attending tugs to call another tug to assist CMA CGM Bellini.

Meanwhile, CMA CGM Bellini’s third mate saw all except one of the headlines were paying out and, assisted by 2 other crew members, attempted to heave them in. On the bridge, the chief mate officer called the engine room and instructed the duty engineer to standby the main engine and bow thruster before calling the master.

At 0642, a tug arrived to assist and began pushing up on CMA CGM Bellini’s starboard shoulder. At this time, APL Scotland was manoeuvring ahead of CMA CGM Bellini, and the pilot was using its engine intermittently at dead slow ahead to counteract the current and keep the ship stationary off the berth. When CMA CGM Bellini’s master arrived on the bridge at about 0650, its bow was slowly returning alongside the wharf.

By 0655, CMA CGM Bellini’s bow thruster was being used and at 0705, the ship was alongside with the crew working with shore personnel to replace the parted lines. The master then contacted VTS and informed the duty VTSO of the situation while the chief mate attended to the mooring arrangements.

By 0730, all mooring lines had been resecured. At 0800, the chief mate advised the master that the ship was again fast alongside before informing VTS that the situation was under control. The attending tug was released and shortly afterwards, cargo operations resumed.

Context

OOCL Brisbane

OOCL Brisbane was built in 2009 by Samsung Heavy Industries, South Korea, registered in Hong Kong and classed with the American Bureau of Shipping. At the time of the occurrence, it was owned by Newcontainer No.138 (Marshall Islands) Shipping and managed and operated by Orient Overseas Container Line, Hong Kong.

The 4,578 TEU[6] container ship had an overall length of 260 m, a moulded breadth of 32.25 m and a depth of 19.30 m. At its summer draught of 12.62 m, it had a deadweight of 50,575 t.

Upon its arrival in port, OOCL Brisbane had a crew of 25 Singaporean, Chinese and Filipino nationals, all suitably qualified for their positions held on board.

Mooring equipment

At the time of the breakaway, each of the 16 polyamide (nylon) mooring lines used to secure OOCL Brisbane alongside (Figure 3) had a minimum breaking load of 72.6 t, while each mooring winch had a brake holding capacity of 52.8 t. Following the breakaway, a surveyor inspected the mooring lines and equipment, as well as the service records relating to them, and determined that prior to the incident, the mooring lines, winches and gear had been properly maintained and were in serviceable order.

Delos Wave

Delos Wave was a 2,824 TEU container ship built in 2007 by HD Hyundai Mipo, South Korea. The 222 m ship had a moulded breadth of 30 m, a depth of 16.80 m and a deadweight of 39,357 t at its summer draught of 12 m.

The ship was registered in the Marshall Islands and classed with Nippon Kaiji Kyokai (ClassNK). At the time of the occurrence, it was owned by Box Carrier Corporation and managed and operated by Nautical Carriers Incorporated, Greece.

Propulsive power was provided by a single Hyundai B&W 2‑stroke, single‑acting diesel engine that developed 25,270 kW at 104 rpm. The main engine drove a single, fixed-pitch propeller, which gave the ship a service speed of 22 knots.

The ship was manned by 23 suitably qualified Ukrainian, Georgian, Moldovan, Greek and Filipino nationals.

Pilot

Delos Wave’s pilot had trained and qualified as a licensed (unrestricted) Brisbane pilot when Poseidon Sea Pilots (PSP) commenced the provision of pilotage services for the port in January 2022. The pilot had previously been a pilot in the Queensland ports of Townsville and Gladstone for 6 years.

CMA CGM Bellini

CMA CGM Bellini was built in 2004 by Samsung Heavy Industries, South Korea, registered in Malta and classed with Bureau Veritas. At the time of the breakaway, the 5,782 TEU container ship was owned, managed and operated by CMA CGM, France.

The ship had an overall length of 277 m, a moulded breadth of 40 m and a depth of 24.33 m. At its summer draught of 12.53 m, it had a deadweight of 72,500 t.

CMA CGM Bellini had a crew of 20 Croation, Montenegrin, Sri Lankan and Filipino nationals, all suitably qualified for their positions held on board.

Mooring equipment

At the time of the breakaway, each of CMA CGM Bellini’s 14 nylon (polyamide) mooring lines used to secure the ship alongside (Figure 7) had a minimum breaking load of 96.3 t. The ship’s maintenance records indicated they were in good condition. The mooring equipment maintenance records also indicated that the mooring winches and winch brake linings complied with the requirements of class and the ship’s safety management system.

APL Scotland

APL Scotland was built in 2001 by Samsung Heavy Industries, South Korea, registered in Singapore and classed with Det Norske Veritas (DNV). The 5,510 TEU container ship was owned by CMA CGM Asia Pacific Liner and managed and operated by CMA CGM Asia Shipping, Singapore.

APL Scotland had an overall length of 277 m, a moulded breadth of 40 m and a depth of 24.30 m. At its summer draught of 14 m, it had a deadweight of 68,017 t. Propulsive power was provided by a single Samsung-MAN B&W 2‑stroke, single‑acting diesel engine that developed 54,840 kW at 94 rpm. The main engine drove a single, fixed-pitch propeller, which gave the ship a service speed of 23.5 knots.

The ship was crewed by 24 suitably qualified Chinese, Sri Lankan and Filipino nationals.

Pilot

APL Scotland’s pilot had extensive pilotage experience in various ports in Australia before obtaining an unrestricted pilot licence for Brisbane in 2021 after joining PSP.

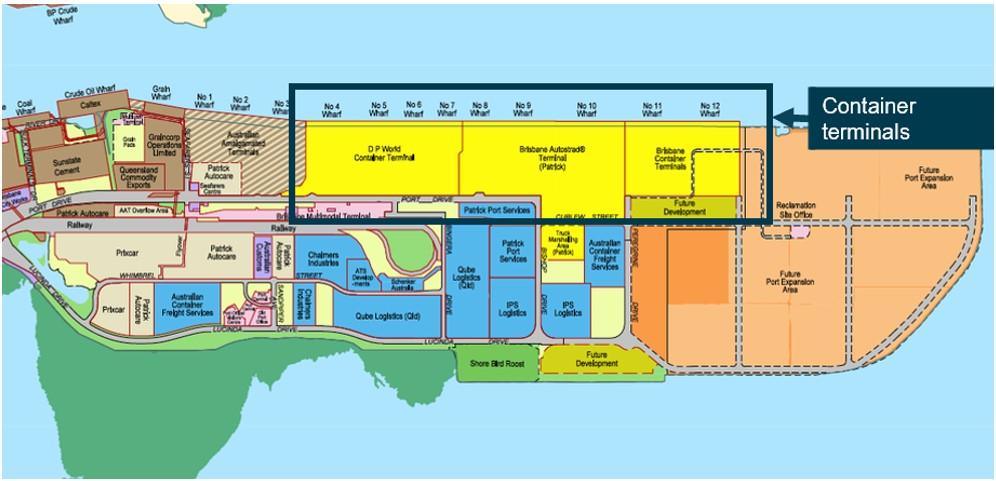

Port of Brisbane

The Port of Brisbane (Figure 10) is located at the mouth of the Brisbane River in south‑east Queensland. It is one of Australia’s largest and most diverse multi-cargo ports, with 28 operating berths facilitating the handling of containers, general cargo, motor vehicles and bulk, as well as a dedicated international cruise ship terminal.

Figure 10: The Port of Brisbane

Source: Port of Brisbane

Each year, approximately 2,150 ships visit the port, which handles approximately $55 billion annually in international trade, including 50% of Queensland’s agricultural exports and 95% of its motor vehicles and containers. In the 2021–22 financial year, the port handled 32 million tonnes of cargo, including 1.53 million containers.

Under Queensland’s Transport Operations (Marine Safety) Act 1994, control of navigation in the port is the responsibility of the regional harbour master (RHM) appointed by Maritime Safety Queensland (MSQ). In 2010, the port was privatised and, under a 99-year lease from the Queensland Government, is managed and developed by the Port of Brisbane (PBPL).[7] MSQ and the PBPL were jointly responsible for managing the safe and efficient operation of the port.

The Brisbane port limits encompass a significant area of Moreton Bay and extend to the northern end of the bay with about 45 miles[8] from the pilot boarding ground to river entrance beacons. The RHM’s area of responsibility extends beyond the port limits to include areas of other commercial and recreational activities, including Moreton Bay, the Brisbane River upriver from the port and the coastal sea area to about 45 miles further north of the port limits.

At the time of the occurrences, the port provided an equivalent of eight 300 m container berths (numbers 4 to 11) at Fisherman Islands (Figure 11). The design depth off the wharf face was 14 m and each berth pocket was 55 m wide.

Figure 11: Fisherman Islands container berths

Source: Port of Brisbane, annotated by the ATSB

Pilotage

All ships over 50 m in length calling at Brisbane were required to take a pilot. The pilot boarding ground was situated 3 miles south‑east from Point Cartwright.

Pilot transfers were conducted by pilot boat, normally operating out of Mooloolaba Boat Harbour, located at the mouth of the Mooloolaba River near the north‑western shore of Point Cartwright. During rough sea conditions, the bar at the river entrance sometimes became hazardous for pilot boats to cross. In such circumstances, the boats operated from Scarborough, a short distance north‑west of Redcliffe.

Vessel traffic service

The Brisbane vessel traffic service (VTS) was the principal resource available to the RHM to manage the movement of ships approaching, departing and operating within the Brisbane VTS area, which includes all areas within the Brisbane port limits and the compulsory pilotage area.

The service was provided by MSQ and manned 24 hours per day by qualified vessel traffic service operators (VTSO).

Brisbane River

The Brisbane River is the longest river in south‑east Queensland, travelling 344 km from Mount Stanley and flowing through the city of Brisbane and its port before emptying into Moreton Bay on the Coral Sea.

The Brisbane River basin drains a catchment of about 13,560 square kilometres to the mouth of the river. The river system includes 2 water storage and flood mitigation dams – Somerset Dam on an upriver tributary, which drains to Wivenhoe Dam on the Brisbane River (Figure 12).

About half of the catchment is above Wivenhoe Dam, which is situated about 150 km from the mouth of the river. Seqwater estimated that water released from Wivenhoe Dam takes about 30 hours to reach the port. Wivenhoe Dam stores a significant volume of inflow water, reducing the Brisbane River level to mitigate the risk of flooding.

Figure 12: Wivenhoe and Somerset dams

Source: Queensland Government

While the frequency and severity of floods has diminished since the 1985 construction of Wivenhoe Dam, severe flooding along the Brisbane River can still occur. Such events may result in widespread damage to surrounding areas, as documented during significant flood events in January 2011 and February 2022.

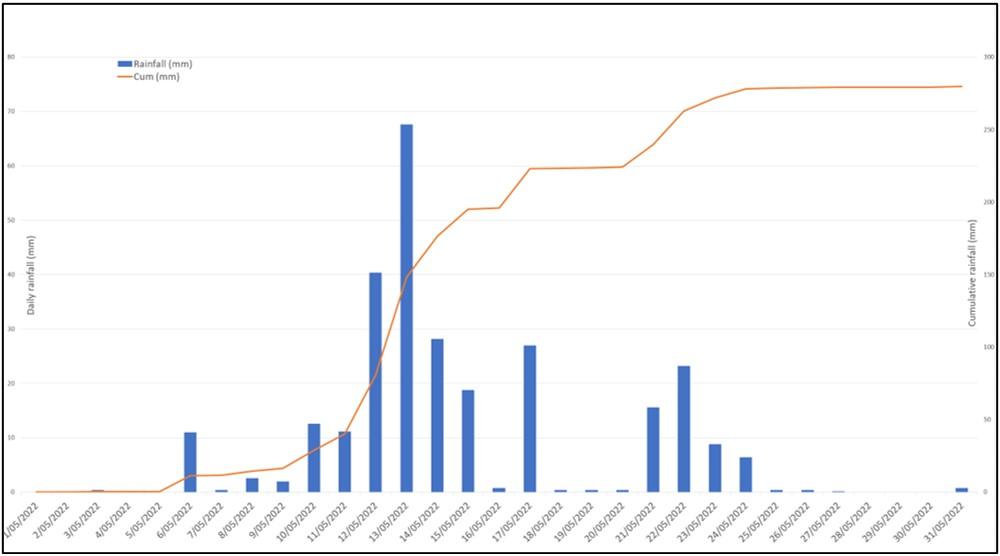

Weather event

In early May 2022, onshore winds and a low-pressure trough across eastern Australia resulted in substantial rainfall in the east of the country, in addition to strong winds and hazardous surf conditions along much of its eastern seaboard. In south‑east Queensland, rainfall was significantly above average, with most locations recording more than twice the average for the month. In the Greater Brisbane area, rainfall was heaviest between 11 and 14 May, peaking on 13 May. By 16 May, the total accumulated monthly rainfall was 196 mm and by 20 May, this total had increased to 225 mm (Figure 13). Brisbane’s total rainfall for the month was 280 mm, 397% of the long-term average of 70.6 mm and the city’s wettest May since 1996.

Figure 13: Daily and cumulative rainfall for Brisbane in May 2022

Source: Bureau of Meteorology, compiled by the ATSB

Impact on port and mooring conditions

Following these occurrences, PBPL and MSQ engaged Seaport OPX, a specialist provider of hydrodynamic modelling and digital port solutions, to investigate the circumstances of the breakaways. This was to assist port management to evaluate existing mooring practices and procedures at Fisherman Islands.

Seaport OPX used 3D hydrographic modelling and mooring analysis software to simulate and assess the environmental and dynamic conditions that may have contributed to each breakaway. In its investigation report, Seaport OPX noted that the complexity of the physical processes and their interactions on the moored ships were difficult to evaluate, even with the use of advanced numerical modelling tools. They were however able to provide insight into the factors that probably contributed to the breakaways.

Increased river currents

Following heavy rainfall over the Brisbane River catchment areas, the resulting freshwater inflows to the river were observed to generate abnormally high currents in the port, including along the Fisherman Islands berths. These inflows coincided with a perigean[9] spring tide from 16 May, which resulted in a higher-than-average spring tidal range during the time of both breakaways, thereby further increasing ebb current flows.

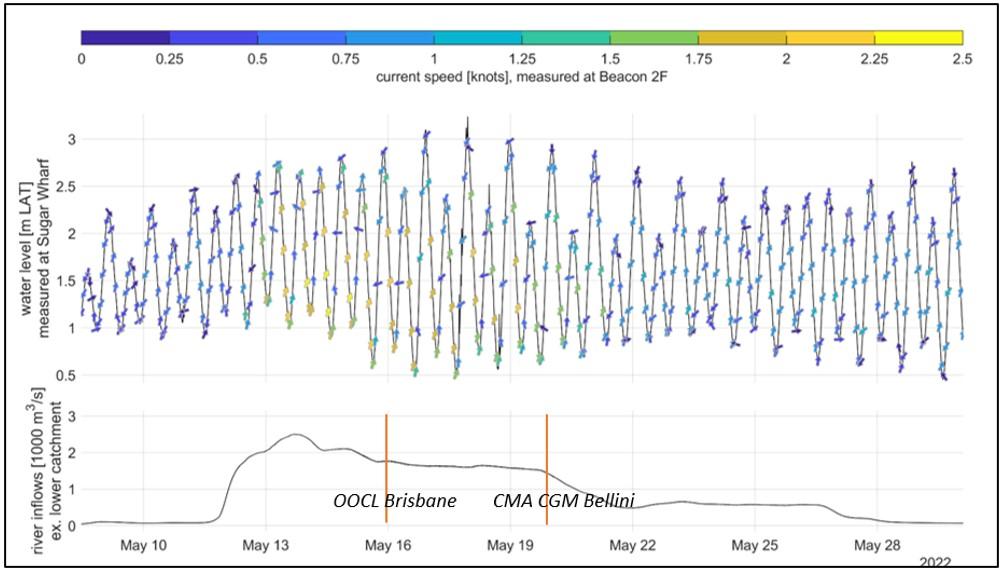

Seaport OPX estimated that at the time of both breakaways, freshwater discharges into the lower catchment were approximately 1,500 cubic metres per second (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Catchment inflows and subsequent water levels and current speeds

Source: Seaport OPX, annotated by the ATSB

The current meter at 2F beacon was installed at a minimum water depth of approximately 5 m. Simulation results produced by Seaport OPX for the time of the breakaways indicated that maximum surface current at the Fisherman Islands berths was greater than that recorded by the meter and estimated the ebb flows to be 1.5 to 2 knots higher than a normal spring ebb tide. Current speed was also found to vary across the channel, with lower speeds closer to the wharf.

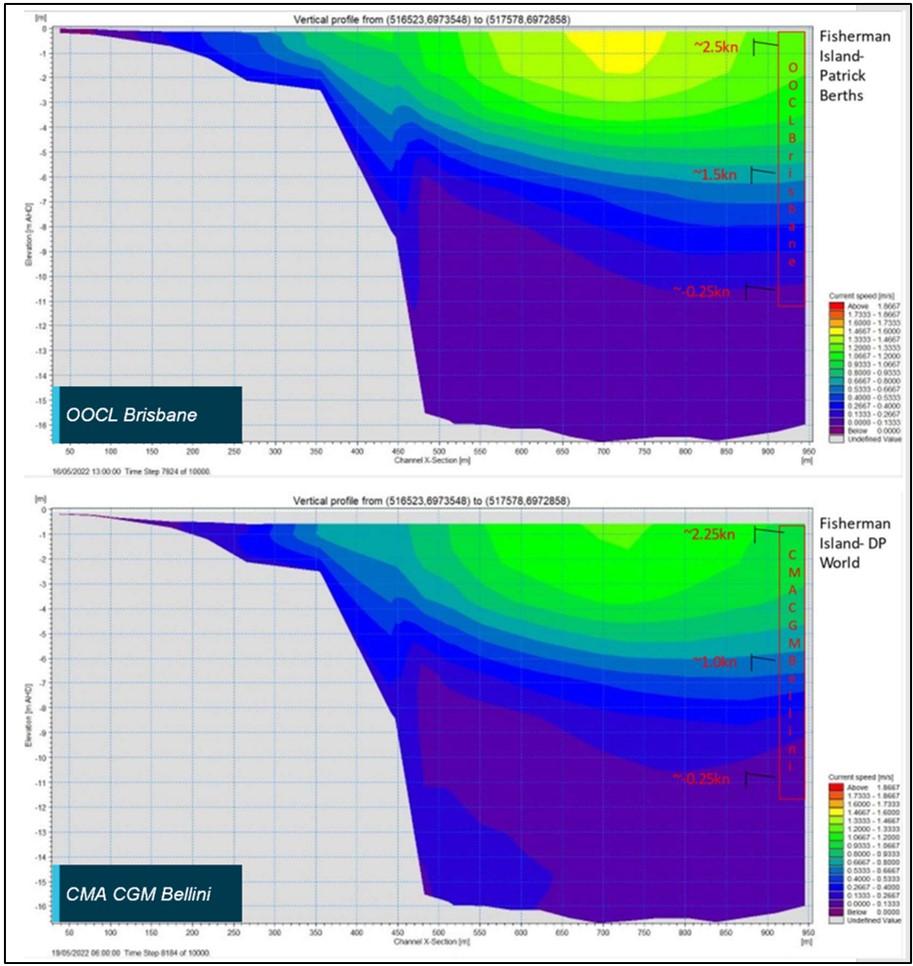

The report stated that hydrodynamic conditions ‘were complicated by the likely presence of a strong density-driven stratification of the flows over the draught of the moored vessels, with higher speeds and lower water density near the surface compared to at the bottom of the draught of the vessel’ (Figure 15). According to modelling, the vertical stratification of the flows over the draught of the moored ships meant that denser saline water could flow slowly upriver even while the freshwater surface layers were flowing seaward at up to 3 knots.

Figure 15: Cross-section of simulated current speeds

Source: Seaport OPX, annotated by the ATSB

The report noted that these aspects could not be fully integrated into the mooring analysis software and increased the uncertainty of the analysis. While the forces simulated for the increased river current velocities introduced increased forces on both ships’ mooring systems, the model did not predict that the mooring line minimum breaking loads, nor the loads at which the mooring winches were expected to render, would be exceeded under those environmental conditions alone.

However, Seaport OPX also advised that limitations in the simulation software also probably resulted in the calculated line forces and the ship’s yawing motions being underestimated for each event.

Passing ship interaction

When a ship passes close to a berthed ship, there will be hydrodynamic interaction between them, potentially causing the berthed ship to move. The magnitude of the hydrodynamic forces, which may cause the berthed ship to surge, sway and/or yaw, will depend on factors such as the speed of the passing ship, the passing distance, both ships’ under-keel clearance and relative displacements and whether the berth is open to water on all sides or only on one side, for example, at a river berth.[10]

The magnitude of these interaction forces and the risk of a breakaway can be reduced by the following measures as appropriate:

- ensuring ships pass at the minimum speed for steering

- providing a greater distance margin when manoeuvring in proximity to berthed ships

- reducing water flow disturbances through greater reliance on tugs to manoeuvre (as opposed to using the ship’s engine)

- in ports that experience fast-flowing water currents, planning ship movements to avoid peak ebb and flood tidal flows to reduce the risk of interaction with berthed ships.

Generally, these considerations are well known to pilots, who are experts in ship handling and have detailed local knowledge of the port, including factors related to tidal conditions and under‑keel clearances.

Prior to each occurrence, OOCL Brisbane and CMA CGM Bellini had been berthed alongside for more than 20 hours. Each breakaway occurred shortly after another ship (Delos Wave and APL Scotland, respectively) had passed in the adjacent channel and started manoeuvring into the berth ahead.

The Seaport OPX model indicated that the observed surging and yawing motions of OOCL Brisbane and CMA CGM Bellini were likely exacerbated by the effect of the passing ship’s surface displacement wave interactions.

The interactions were also shown to be ‘enhanced by strong ebb currents, which effectively increased the through-water speed of the passing ships, resulting in additional squat and thus a greater drawdown wave.’ However, the model predicted that this effect alone was not significant enough in either occurrence to exceed the berthed ship’s mooring system capacities.

Effect of a ship berthing ahead

In its analysis, Seaport OPX submitted that the increased surface currents at the berths were likely further accelerated by the berthing of Delos Wave and APL Scotland ahead of OOCL Brisbane and CMA CGM Bellini, respectively. The report stated that:

Hydrodynamic processes associated with strong surface currents generated during significant freshwater river discharges… were likely further accelerated locally by the berthing of a vessel immediately upriver… initiating lateral force and yaw moments on the moored vessels through mechanisms that could include:

- inherent turbulence in the incident mean flows

- blockage effect interactions between the upriver berthing vessel and the berth structure and the seabed, resulting in uneven acceleration of flows and hydrodynamic forces around and under the downstream moored vessel

- vortex shedding around the blunt stern hull form generating alternating crossflow forces on the vessel hull

- variations in current speed forcing over the draught due to strong stratification and unequal forcing on the vessel hull

- internal wave effects

The report noted that the use of the main engine during the berthing of Delos Wave and APL Scotland introduced additional hydrodynamic interactions on the berthed ships which likely contributed to both breakaway occurrences.

Wind

The Seaport OPX model simulation indicated that the mild to moderate winds observed at the time of each occurrence were unlikely to have contributed significantly to the breakaways.

Maritime Safety Queensland

Marine legislation in Queensland is administered and implemented by Maritime Safety Queensland (MSQ), a state government agency within the Department of Transport and Main Roads (DTMR). As such, MSQ is responsible for safety oversight of pilotage, pollution protection services, vessel traffic services (VTS) and the administration of all aspects of ship registration and marine safety in the state.

The agency’s core focus is the preservation of life and property in the state’s waters and in the prevention of, and response to, ship-sourced pollution and other maritime emergencies and disasters. This includes the development of hazard‑specific plans.

Queensland’s 5 maritime regions, including the Brisbane region, are each controlled by a regional harbour master (RHM).[11] For their respective region, each RHM is responsible for:

- improving maritime safety for shipping and small craft through regulation and education

- minimising ship sourced waste and providing response to marine pollution

- providing essential maritime services such as pilotage, vessel traffic services and aids to navigation and

- encouraging and supporting innovation in the maritime industry.

Port Procedures and Information for Shipping manual

The Port of Brisbane had a publicly available Port Procedures and Information for Shipping manual (PPM) which defined the standard procedures to be followed in the port’s pilotage area. The PPM also contained information and guidelines to assist the masters, owners, and agents of ships arriving in the port and traversing the area, including details of the services, regulations and procedures established for the port.

Port tidal and weather information

The PPM provided a basic description of the port and its facilities. A general description of environmental conditions that may be experienced in the port provided that:

The majority of berths at the port of Brisbane are located at Fisherman Islands, at the mouth of the Brisbane River which extends into Moreton Bay. The area is very exposed to the prevailing winds which include fresh to strong SE trades year-round, strong N/NE sea breezes in the afternoons during the summer months and strong to gale force SW/W winds in the late winter months.

Advice that the river on which the port was located was subject to dam releases and flooding was not contained within the manual.

General tidal information for the port was also provided in the PPM, including the mean spring tidal range (1.8 m) and the location of tide gauges. The PPM sought to remind port users that tidal ebb and flows can begin or continue after the times of high or low water at various localities in the Brisbane River, noting that ‘this should be borne in mind when booking ships in for ‘head up’ or ‘head down’ berthing’.

The PPM advised that tidal stream information for the port was available from the office of the RHM. Additionally, VTS could provide real-time tidal/current conditions and weather information from tide gauges and weather stations within the port, as well as weather forecasts, shipping schedules, navigational warnings and any other special operational requirements.

Fisherman Islands berth information

The PPM provided a description of the different berth locations in the port and any special requirements and precautions to be observed at each location. For Fisherman Islands berths, the PPM identified strong south‑easterly offshore winds as a factor requiring extra attention to ensure ships were moored safely. While the PPM highlighted that this responsibility lay with the ship’s master, it noted that pilots and terminal operators would provide support, including recommendations for mooring arrangements.

Ship interaction provisions

Berth surging and interaction in the Brisbane River was highlighted as a risk in the PPM for berths upriver from Pelican Banks. It stated that berth surge is caused by a variety of environmental factors, poor mooring arrangements and overall ship preparedness, and normally triggered by a ship passing the berthed ship. The PPM warned that surge events could result in parted mooring lines, damaged gangways, impacts to the environment and injury to persons. The PPM provided a list of berths within the port that were prone to ship interaction and detailed precautions that were to be taken by both passing ships and ships alongside. Berths at Fisherman Islands, where the adjacent channel is wider than for those upriver, were not included in the list.

To assist in the management of berth surge, the PPM stipulated an operational speed limit of 6 knots through the water for ships with draught of more than 3 m. This restriction applied only when passing ships upriver from Fisherman Islands berths.

Towage requirements

The PPM specified towage requirements for ships berthing and unberthing at Fisherman Islands. Two tugs were normally required for ships more than 150 m in length, while ships more than 300 m long required a third tug to be turned around in the channel. The PPM stated that tug requirements were based on the ship stemming the current when berthing and departing and that manoeuvring with the current on the ship’s stern may require the use of an additional tug. Under normal environmental conditions, a tug could be substituted by an efficient bow thruster.

Extreme Weather Event Contingency Plan

The Queensland Government had published an Extreme Weather Event Contingency Plan (EWE) for each maritime region. Each plan detailed the response required from ship masters and owners to different warning and/or alert levels in that region.

The Brisbane EWE (2021–2022) was intended to address the range of adverse weather events that may affect the region, such as summer storms, river flooding or the effects of a cyclone. It was the responsibility of ship owners and masters to take the necessary action within the context of the official weather warnings to protect their passengers, crew and ships, and comply with any directions from the RHM. This included the requirement for all ships to have a safety plan.

The EWE noted that, at times, it may be necessary for the RHM to give directions in relation to the operation and movement of ships when entering, operating in or leaving the pilotage area. This included the evacuation of commercial ships to sea and closure of the pilotage area to all marine activities and operations.

The plan outlined an incremental response encompassing prevention, preparedness, response and recovery phases. The plan aimed to allow appropriate actions in response to the imminent threat to be planned and implemented. Under the EWE, the primary objective was to have the port area secure and safety plans enacted at least 6 hours before the weather event occurred.

Vessel traffic service extreme weather event procedure

An internal extreme weather event procedure provided information to VTSO’s for such events in the Brisbane region and the responses required. It stated that the procedure was informational in nature and was to accompany additional procedures outlining specific VTSO responsibilities and actions to be undertaken during extreme weather events.

The procedure outlined some general trigger points and related response actions for significant storm, wind and surf warnings, as well as notifications relating to potential dam release and flood warnings for the Brisbane River.

General dam release and flood warning response actions included monitoring flood effects on tidal flows, debris in the river and weather warnings. Port users were to be kept informed of the situation through appropriate means of communication.[12] Individual, high‑risk commercial ships and facilities could also receive specific advice and instructions through direct messaging from the RHM. Other, relevant, flood-related precautions contained in the procedure are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Selected VTS extreme weather event procedure flood warning related actions

| Trigger event | Response |

| Wivenhoe Dam water release notification |

|

| Minor flood warning |

|

| Moderate flood warning |

|

| Major flood warning |

|

| Note: The table does not show all actions contained in the procedure. | |

Severe weather information

Advice for severe weather was publicly available via the MSQ website.[13] Among other information, this included links to state and regional extreme weather event contingency plans.

Weather monitoring

The principal source of weather forecasts, warnings and information for MSQ (via a subscription service) was BoM. Brisbane VTS received forecasts and warnings from BoM for weather, storm, rain, wind and flood conditions. The information received was passed on to port users by VTS via VHF channel 67 and other means such as email and phone messaging, as required.

In addition, MSQ obtained weather data from a network of 6 tide gauges and 12 weather stations located in the port and surrounding areas, as well as the single current flow meter. The current speed from the meter was prominently displayed on an electronic display board in the VTS centre.

Brisbane VTS routinely received weather reports from several sources including Seqwater and the PBPL Nonlinear Channel Optimisation Simulator system (NCOS). The NCOS system provided wind forecasts and automated warnings to VTS for the port and surrounding Moreton Bay areas. Advice from Seqwater regarding water releases (forecast and actual) from Wivenhoe Dam was also provided to VTS.

Risk management arrangements

The tools available to the RHM’s team for identifying and mitigating the risks that extreme or adverse weather posed to port operations consisted of the PPM, EWE and VTS extreme weather event procedure. The ATSB also reviewed email correspondence between the RHM and other MSQ officers between 5 and 23 May. The email archive documented MSQ’s response to notifications and warnings it received regarding forecast rain, dam releases and potential flooding. Further emails from the same period documented MSQ’s subsequent correspondence with port stakeholders such as PSP, ships’ agents, terminal operators and other government agencies.

The correspondence indicated that MSQ began preparing for potential port schedule disruptions on 6 May, following receipt of the notifications and warnings. The preparation actions included increased monitoring of weather warnings and current meter readings, suspension of immobilisation permits, requesting that ships deploy additional mooring lines and the provision of information and advice to various stakeholders and port users. While these actions implemented by MSQ reflected those documented in the VTS extreme weather event procedure, they were developed in isolation rather than via the involvement of other stakeholders with specialist marine knowledge, such as PSP. Throughout this period, the RHM and PSP were also required to concurrently manage disruptions due to rough seas and swell at the pilot boarding ground (PBG).

As per the EWE, additional restrictions at Fisherman Islands, while not expressly provided in the PPM or VTS extreme weather event procedure, were implemented at the discretion of the RHM to mitigate the risk to port safety posed by the increased current flows. Ships more than 300 m long were not permitted to berth and all new arrivals were required to berth port side alongside (head‑up). New arrivals to berths upstream of Pelican Banks were also suspended.

Decisions relating to these restrictions were primarily informed by the RHM’s appraisal of current meter observations and the response measures implemented were consistent with the documented procedures in place at the time. The email correspondence did not refer to any specific pre-determined trigger points or safe operating limits at which additional measures might be required, or when river current strengths might be considered too strong for the safe continuation of ship movements.

On the morning of 16 May, prior to the OOCL Brisbane breakaway, VTS notified port stakeholders, including PSP, that some of the restrictions at Fisherman Islands would be eased from the following day. This would allow some selected ships to berth starboard side alongside (head-down) at Fisherman Islands, subject to the specific berth, each ship’s particulars and observed current flow conditions. Movements to berths upriver from Pelican Banks were also to resume, subject to additional restrictions.

Following the breakaway of OOCL Brisbane, the RHM decided that the restrictions that were to be lifted would instead be maintained, while planned movements upriver from Pelican Banks were permitted to proceed from 17 May. On 18 May, the RHM lifted the restriction on ships more than 300 m long berthing at Fisherman Islands. At the time of the breakaway of CMA CGM Bellini, restrictions and precautions for ships less than 300 m in length had not been changed or expanded on since the earlier breakaway 4 days prior.

Pilotage

Pilotage is the key risk control to ensure safe movement of ships in the port. Pilots are competent ship handlers with detailed local knowledge, including currents, tidal variations and other relevant factors. Pilotage providers are responsible for managing the safety risks associated with delivering this specialist service and an essential resource for port authorities, particularly in abnormal weather conditions.

Since 1 January 2022, pilotage services for Brisbane have been provided by Poseidon Sea Pilots (PSP).

Safety management system

As part of its obligations for ensuring safe delivery of pilotage services, PSP maintained a Pilotage Operations Safety Management System (POSMS). It was intended to complement the PPM and, in the event of inconsistency, the PPM was to take precedence. The POSMS was reviewed and endorsed by MSQ and subject to an annual audit schedule.

The POSMS contained procedures and guidance for the preparation and conduct of pilotages, including passage planning. These provisions made it the responsibility of the assigned pilot to confirm the environmental conditions at the time of each scheduled pilotage, including current speed and direction. While some guidance was provided for wind conditions, including force calculations for wind speed versus exposed ship area, hazardous conditions associated with other factors such as river flood or abnormally fast current flows were not mentioned.

The POSMS described general principles and processes for risk management and the responsibilities of key management personnel for managing issues related to the safe, effective and efficient delivery of the pilotage service. These responsibilities extended to engagement with pilots, PBPL, ships’ agents and VTS on operational issues and, where required, consultation with the RHM to discuss closure of the port during adverse weather events. Specific operational risks associated with environmental conditions were not included. There were no procedures contained within the POSMS to describe when and how PSP management would initiate its preparation and response to conditions which may negatively impact the safety of its operations.

The POSMS did not provide for any formal process or structure to address and document PSP’s participation in the management of wider port and regional safety to which the pilotage service provider is an important and major contributor. While PSP management supported decisions taken by MSQ and the RHM’s directions in response to the weather event, it was not directly involved in any formal process for assessing and addressing risks affecting pilotage, such as increased river current flows.

Previous occurrences

On 26 February 2022, the container ship S Santiago broke away from its berth at Fisherman Islands when its mooring lines parted as another container ship was being berthed ahead and upriver of it. S Santiago was resecured alongside its berth 30 minutes later, with tug assistance. At the time, the ship’s master stated that a 20 to 25 knot wind had pushed the stern away from the wharf, resulting in several mooring lines parting. At the time, the river was in flood following an extreme weather event.

The following day, as the weather event continued, the oil products tanker CSC Friendship broke free from its berth at the Ampol products wharf at Lytton, upstream of Fisherman Islands. At the time, a persistent ebb current was flowing at about 4.5 knots. The ship was swept across the adjacent channel and grounded about 400 m downstream, on the opposite side of the river. The ship remained fast aground until refloated at 0500 the next day.

A subsequent ATSB investigation (MO-2022-003) identified that the river current had exceeded the limits for the design of both the berth and the ship’s mooring arrangements. The investigation found that deteriorating conditions associated with the flood event and subsequent increased safety risk to shipping and the port were foreseeable. The BoM had issued warnings of the impending event from 21 February, which provided sufficient information to identify the increased likelihood of a breakaway.

The investigation identified that MSQ did not have structured or formalised risk or emergency management processes or procedures and consequently, it was unable to adequately assess and respond to the risk posed by the river conditions and current.

Additionally, PSP, as the port’s pilotage provider, did not have procedures to manage predictable risks associated with increased river flow or pilotage operations outside normal conditions. As a result, PSP had not properly considered risks posed by the increased river flow and taken an active role until after the breakaway.

Safety analysis

Introduction

In the early weeks of May 2022, areas of south-eastern Queensland, including catchments of the Brisbane River, experienced heavy rainfall that resulted in a series of controlled dam water releases upriver from the Port of Brisbane. The subsequent high freshwater inflows into the river resulted in increased current speeds through the port, exposing ships to the risk of breaking free from their berths.

On 16 May 2022, the container ship OOCL Brisbane broke away from its berth at Fisherman Islands after its mooring lines parted. This occurred immediately after another ship, Delos Wave, had passed in the adjacent channel and manoeuvred to the berth immediately ahead of it.

Four days later, another container ship, CMA CGM Bellini, was alongside a berth at Fisherman Islands when 2 of its forward mooring lines parted and its bow drifted off the berth. As in the breakaway on 16 May, another ship, APL Scotland, had just passed and berthed ahead of CMA CGM Bellini.

The breakaways

There was no evidence of any defective mooring equipment on either OOCL Brisbane or CMA CGM Bellini, which could have contributed to the occurrences. Each ship had been secured with sufficient mooring lines, including additional lines required by the regional harbour master (RHM) to mitigate the increased river current.

At the time of the occurrences, freshwater inflows to the river from heavy rainfall and dam releases were estimated to be 1,500 cubic metres per second, resulting in ebb current flows at the port about 1.5–2 knots higher than observed during a normal spring ebb tide. The ebb tidal flows were also amplified by the advent of a perigean spring tide from 16 May which increased the average spring tidal range during the time of both breakaways.

Due to probable current variation with depth, surface current speeds at Fisherman Islands berths were likely higher than indicated by the port’s only current flow meter, located upriver from the berths. Both breakaways occurred on the mid to late ebb tide, when current flows were near their maximum. These conditions resulted in increased loads on the ships’ moorings.

However, both OOCL Brisbane and CMA CGM Bellini had been berthed alongside for over 20 hours, during which time there had been no issues with the moorings of either ship. A mooring analysis conducted by a specialist hydrodynamic modelling company commissioned by port management later estimated that the additional mooring loads created by the strong ebb currents alone should not have exceeded the mooring equipment capacities of either ship.

Significantly, each breakaway occurred shortly after another ship (Delos Wave and APL Scotland, respectively) passed in the adjacent channel and began manoeuvring into the berth ahead. Given the timings and the above finding of the hydrodynamic modelling specialist, it is almost certain that the interaction forces and water flow disturbances created by the proximity of the berthing ships contributed to both breakaways.

The speed and distance at which Delos Wave and APL Scotland passed the berthed ships were within the operating limits and usual pilotage practices for normal conditions, including usual river flow. The strong ebb current flow, however, meant the passing ships’ effective speed through the water (as opposed to speed over ground) increased the effect of surface displacement wave interactions associated with their movement, causing the berthed ships to surge and yaw. Further, the hydrodynamic modelling indicated that the forces associated with the ships passing were probably insufficient on their own to have led to the breakaways.

When Delos Wave and APL Scotland manoeuvred ahead of the berthed ships, the already high surface current speeds at the berths were further accelerated due to a complex range of hydrodynamic factors. These included interactions between the upstream berthing ship, the berth structure and the seabed, as well as disturbances created from the operation of the berthing ship’s main propulsion. These factors, combined with the prevailing environmental conditions at the berths, contributed to the yawing forces on OOCL Brisbane and CMA CGM Bellini and increased the load on their respective mooring systems until they ultimately failed.

Risk management

Maritime Safety Queensland

Effective risk management relies first and foremost on identification of all the relevant hazards. The involvement of personnel/organisations with subject matter expertise and knowledge in that initial process provides the best opportunity to mitigate the associated risk.

Maritime Safety Queensland’s (MSQ) procedures for managing risks posed by extreme and adverse weather events provided general guidance on precautionary steps to be taken in the event of river flood and increased current flows. However, they did not provide for any formal risk assessment arrangements involving specialist input from key stakeholders, including the port’s pilotage provider, Poseidon Sea Pilots (PSP). The collective expertise of PSP’s pilots in respect to ship handling (including factors pertaining to ship interaction) was a valuable resource available to the regional harbour master (RHM) for consultation and advice.

In this case, MSQ received dam water release and flood notifications and subsequently identified that resulting high river current speeds would increase the risk of a breakaway. In response, MSQ increased its monitoring of current meter data and implemented precautions and restrictions at Fisherman Islands. While these measures were aimed at addressing increased current flows, the more complex hazard of increased hydrodynamic interaction between passing and berthed ships was not identified.

While that complexity meant that the hazard may not have been obvious prior to the OOCL Brisbane breakaway, it was readily identifiable following that initial occurrence. Had MSQ and PSP engaged in a re-assessment of the risk and existing precautions it would have probably resulted in considering additional controls such as:

- restricting ship movements during ebb tides

- minimising passing speeds

- maximising passing distances

- the greater use of tugs to minimise use of the ship’s engine.

However, the opportunity to identify such controls was missed as MSQ procedures did not require or prompt formal collaborative risk assessment with PSP and other relevant stakeholders. Consequently, no further controls were in place when CMA CGM Bellini broke away 4 days later in almost identical circumstances.

Further, MSQ procedures did not identify current speed or catchment inflow trigger points to inform its response to the escalating situation. Its procedures for weather event preparedness could have benefited from the routine and early involvement of PSP and other key stakeholders to help establish specific limits and triggers to assist with identifying the need for additional risk mitigation.

Poseidon Sea Pilots

Pilotage is a principal risk control for ensuring the safety of port operations and ship movements. Pilotage service providers should therefore be actively involved in preparations for, assessment of, and response to, any situation affecting shipping in the port.

As weather and river conditions began to impact the port in the days leading up to the breakaways, PSP management received communications from MSQ relating to dam releases, potential flooding and high ebb current flows. These exchanges included information regarding observed current data, the requirement for additional mooring lines and movement restrictions implemented by the RHM.

While PSP complied with the RHM’s directions, as detailed above, it was not actively involved in any formal process to identify and assess potential risks that the conditions would pose to pilotage operations. Greater involvement of PSP would have increased the likelihood that all hazards associated with the increased river flow were identified and addressed, particularly following the initial breakaway.

The ATSB found that the company’s pilotage operations safety management system (POSMS) only contained procedures for conducting ships in normal conditions. It did not identify flooding or high current flows as a hazard that might affect pilotage operations nor contain any guidance on how these conditions would be managed. Consequently, the POSMS did not address all the operational risks that PSP pilots could be expected to manage when conducting ships.

Finally, while the POSMS identified the responsibilities of key management personnel for managing issues related to the safe, effective and efficient delivery of pilotage services, procedures detailing how these duties were to be discharged did not exist.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition, ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. Safety issues are highlighted in bold to emphasise their importance. A safety issue is a safety factor that (a) can reasonably be regarded as having the potential to adversely affect the safety of future operations, and (b) is a characteristic of an organisation or a system, rather than a characteristic of a specific individual, or characteristic of an operating environment at a specific point in time. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the breakaway occurrences involving OOCL Brisbane and CMA CGM Bellini in the Port of Brisbane, Queensland on 16 May and 20 May 2022, respectively.

Contributing factors

- Heavy rainfall resulted in significant freshwater inflows into the Brisbane River, including from several controlled releases from dams upstream from the Port of Brisbane. The inflows resulted in strong ebb currents through the port which increased the loads on mooring arrangements for ships berthed at Fisherman Islands.

- The combined effects of high ebb current speeds and interaction forces introduced by Delos Wave and APL Scotland when passing and manoeuvring ahead OOCL Brisbane and CMA CGM Bellini, respectively, resulted in the berthed ships’ mooring arrangement limits being exceeded.

- Maritime Safety Queensland and Poseidon Sea Pilots did not have a process to jointly and effectively identify and risk assess the hazards to shipping and pilotage that were outside normal environmental conditions. (Safety issue)

Safety issues and actions

|

Central to the ATSB’s investigation of transport safety matters is the early identification of safety issues. The ATSB expects relevant organisations will address all safety issues an investigation identifies. Depending on the level of risk of a safety issue, the extent of corrective action taken by the relevant organisation(s), or the desirability of directing a broad safety message to the marine industry, the ATSB may issue a formal safety recommendation or safety advisory notice as part of the final report. All of the directly involved parties were provided with a draft report and invited to provide submissions. As part of that process, each organisation was asked to communicate what safety actions, if any, they had carried out or were planning to carry out in relation to each safety issue relevant to their organisation. Descriptions of each safety issue, and any associated safety recommendations, are detailed below. Click the link to read the full safety issue description, including the issue status and any safety action/s taken. Safety issues and actions are updated on this website when safety issue owners provide further information concerning the implementation of safety action. |

Preparedness for adverse weather events

Safety issue number: MO-2022-002-SI-01

Safety issue description: Maritime Safety Queensland and Poseidon Sea Pilots did not have a process to jointly and effectively identify and risk assess the hazards to shipping and pilotage that were outside normal environmental conditions.

Glossary

| BoM | Bureau of Meteorology |

| MEWG | Maritime Emergency Working Group |

| MSQ | Maritime Safety Queensland |

| NCOS | Nonlinear Channel Optimisation Simulator system. The system was developed to provide a near real-time 7-day detailed forecast of environmental conditions and a ship’s under keel clearance. |

| PBG | Pilot boarding ground |

| PBPL | Port of Brisbane |

| POSMS | Pilotage operations safety management system |

| PPM | Port Procedures and Information for Shipping Manual |

| PSP | Poseidon Sea Pilots |

| RHM | Regional harbour master |

| VTS | Vessel traffic service |

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- the master and crewmembers of OOCL Brisbane

- the master and crewmembers of CMA CGM Bellini

- the master and crewmembers of Delos Wave

- the master and crewmembers of APL Scotland

- Australian Maritime Safety Authority

- Maritime Safety Queensland

- Queensland Government

- Bureau of Meteorology

- Seqwater

- Poseidon Sea Pilots

- Port of Brisbane

- Seaport OPX

References

Maritime Safety Queensland 2021, Port Procedures and Information for Shipping – Port of Brisbane, Queensland Government. <https://www.msq.qld.gov.au/shipping/port-procedures/port-procedures-brisbane>

Maritime Safety Queensland 2021, Maritime Safety Queensland Extreme Weather Event Contingency Plan Brisbane – 2021/2022, Queensland Government. <https://www.msq.qld.gov.au/safety/preparing-for-severe-weather>

The West of England Ship Owners Mutual Insurance Association (Luxembourg), Interaction Damage to Vessels Moored Alongside.

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- the master and operators of OOCL Brisbane

- the master and operators of CMA CGM Bellini

- the master and operators of Delos Wave

- the master and operators of APL Scotland

- Poseidon Sea Pilots

- Maritime Safety Queensland

- Australian Maritime Safety Authority

- Hong Kong Marine Department

- Ministry of Transport, Singapore

- Transport Malta

- Maritime Administrator, Marshall Islands

Submissions were received from:

- Poseidon Sea Pilots

- Maritime Safety Queensland

The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2025

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this report is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. The CC BY 4.0 licence enables you to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon our material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] Seqwater (the Queensland Bulk Water Supply Authority) is a statutory authority whose responsibilities include the management of bulk water storage and supply, and flood mitigation for south-east Queensland.

[2] Ship masters request immobilisation to carry out maintenance or repairs on propulsion or other machinery, when it will immobilise the ship for a long period (generally more than one hour).

[3] All ship’s headings are reported in degrees true unless specified otherwise.

[4] Mooring winch drum brakes are designed to slip and allow mooring lines to pay out prior to reaching the minimum breaking load (MBL) of the mooring line.

[5] NCOS: Nonlinear Channel Optimisation Simulator system. In 2017, the Port of Brisbane (PBPL) partnered with DHI and Force Technology to develop NCOS Online. In addition to forecasting environmental conditions, the NCOS mooring tool function could be used to estimate loads on ship’s mooring systems for various environmental parameters, including current speed alongside berths. (Port of Brisbane website)

[6] TEU – twenty-foot equivalent unit – a standard shipping container. The nominal size of a container ship in TEU refers to the number of standard containers it can carry.

[7] Port of Brisbane (PBPL) website: https://www.portbris.com.au/

[8] A nautical mile of 1,852 m.

[9] A perigean spring tide occurs when the moon is either new or full and closest to Earth. During full or new moons, which occur when the Earth, sun, and moon are nearly in alignment, average tidal ranges are slightly larger. This occurs twice each lunar month (about 29.5 days on average).

[10] The West of England Ship Owners Mutual Insurance Association (Luxembourg), Interaction Damage to Vessels Moored Alongside

[11] Regional harbour masters are all officers of Maritime Safety Queensland and report to the General Manager under the Transport Operations (Marine Safety) Act 1994 (TOMSA).

[12] Appropriate means of communications listed included: VHF radio, notices to mariners, email (address groups), short message services, media releases, telephone to individual parties.