What happened

On 11 March 2018, at about 0040 Eastern Standard Time,[1] a Beech B200 aircraft, registered VH‑FDL (FDL) operated by the Royal Flying Doctors Service (RFDS) Queensland Section and based at Cairns, took off from Cairns Airport on runway 15 without the runway lights activated.

At about 0024, an emergency services helicopter departed Cairns with the crew using night vision goggles. The Cairns duty air traffic controller did not activate the runway lights for this departure as it may have interfered with the crew’s night vision goggles. Eight minutes later, at 0032, the pilot of FDL requested clearance from the controller to conduct flight FD493, a medivac flight from Cairns to Townsville. The aircraft had five persons on board; the pilot, two medical crew members, a patient and a passenger (a relative of the patient). The controller granted the clearance and the pilot then requested permission to taxi and backtrack runway 15 to abeam taxiway A2 for departure. In response, the controller issued the instruction to taxi to holding point A3 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Cairns Airport runway, taxiway and terminal map

Source: Airservices Australia, annotated by the ATSB

During taxi, at about 0035, the medical crew informed the pilot that the cabin was not yet secure for take-off. Subsequently the pilot elected to request an extended backtrack to abeam taxiway B2, which was granted by the controller. After issuing this instruction, the controller moved the flight progress strip[2] for FD493 from the taxiway to the runway on the INTAS system.[3]

At 0036, while the aircraft was backtracking runway 15, the controller issued the pilot with a clearance to take-off when ready. On reaching abeam taxiway B2, the pilot turned the aircraft around and immediately commenced the take‑off run on runway 15.

At 0040, the controller instructed the pilot to contact the approach controller. The pilot acknowledged the request and then asked if the runway lights had gone out as the aircraft became airborne. The controller subsequently checked his INTAS display and reported that the lights had not been activated. The flight proceeded to Townsville without further incident.

Cairns Airport

Cairns Airport is a single runway airport with general aviation, domestic and international operations. The airport had a permanently manned air traffic control tower and is active 24 hours per day.

Runway 15 was the active runway on the night of the occurrence. Runway 15 was equipped with both medium and high intensity runway lights (MIRL and HIRL), which were activated by air traffic control. The MIRL are a diffuse light, which can be seen from all directions when in use. The HIRL use a reflector and lens arrangement to control the direction of their light, and can only be seen within approximately 45 degrees of the runway centreline.

In addition to runway lights, Cairns Airport also has taxiway, apron and substantial ambient lighting (predominantly from the two passenger terminals). At the time of the occurrence, the taxiway, apron and terminal lights were on.

The pilot and controller reported that the weather present at Cairns at the time of the occurrence was fine with no obstruction to visibility. The ATIS[4] published at 0031 indicated an air temperature of 25° C, greater than 10 km visibility, ‘FEW’[5] clouds at 1,500 ft and ‘SCT’[6] clouds at 3,000 ft.

Air traffic control

The runway lights were managed by air traffic control (ATC) via the INTAS system control panel. Confirmation of the system state (on/off and intensity) was presented on the INTAS aerodrome layout display and field lighting popup (shown together in Figure 2). The controller could also check the status of the runway lights by looking outside the tower, although HIRL can only be seen by looking towards the southern threshold due to the directionality of their light emission.

The Manual of Air Traffic Services (MATS) section 12.11.1: Operation of lighting procedures, required that runway lighting be in operation ‘prior to aircraft entering the runway’ for departures. Section 12.11.1.6.1 further clarified that runway lighting was required to be activated for all departures, except during daylight hours where visibility was greater than 5,000 m. MATS did not specifically address the operation of runway lighting when aircraft crews are using night vision goggles.

The controller on duty had 20 years’ experience as a tower controller including 17 years at Cairns Tower. The controller had commenced his shift at 2200 on the previous evening and described his alertness at the time of the occurrence as being higher than normal, as there was more traffic than normal at that time of night. The controller was the sole operator in the tower for the occurrence shift, which was standard procedure for that time of night at Cairns Airport.

Airservices Australia and the controller reported that activation of runway lights was a routine task. Checking their status would normally occur during issuing of clearance to enter the runway. Therefore, the task would be performed as part of a sequence that involved several actions including communication, data updating and visual scanning.

The controller reported that he used the ‘LIGHTS’ annunciation on the INTAS flight progress strip display as a memory prompt to aid him to perform the task (Figure 3). He reported that he continuously displayed the ‘LIGHTS’ memory prompt during night-time hours and that this display was independent of the status of the runway lights (on or off).

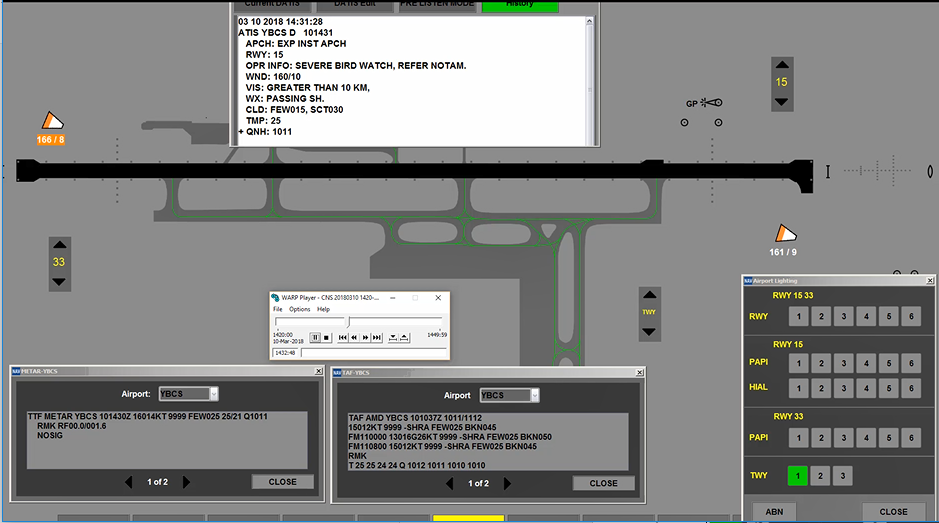

Figure 2: INTAS aerodrome layout display with field lighting popup

A part of the INTAS display, showing airfield lighting system status at time of the incident flight in the field lighting pop-up (bottom right). When activated, the selected light intensity level would have been displayed in green, for example, taxiway (TWY) light level 1 is active.

Source: Airservices Australia

Figure 3: INTAS flight progress strip display

A part of the INTAS display, showing LIGHTS prompt in the right-hand column placed above the runway (RWY) panel.

Source: Airservices Australia

Pilot and aircraft

The pilot in command’s responsibility for ensuring the adequacy of aerodrome lighting was published in the Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP), section 11.9.1: Suitability of aerodromes – General. The pilot’s responsibility included the following conditions:

11.9.1 - b. unless otherwise approved an aircraft must not take off or land at an aerodrome at night unless the following lighting is operating:

(1) for a PVT, AWK or CHTR aircraft: runway edge lighting, threshold lighting, illuminated wind direction indicator, obstacle lighting (when specified in local procedures).

Thus, while not having direct control of the operation of the runway lights, the pilot in command of FDL had a responsibility to ensure that the runway lights were operating before commencing take‑off.

The pilot had approximately 10 years’ experience flying Beech B200 aircraft for the RFDS and had been operating from Cairns Airport for the past 2 and a half years. Due to the nature of RFDS work, night‑time operations were common and the pilot estimated that 40 per cent of his take-off and landings occurred at night.

The pilot started his shift at 1800 the previous evening and received a notification at about 2100 that a medivac flight to Townsville would be required. The pilot submitted a flight plan for the incident flight and conducted a short flight to burn fuel in order to reduce the weight of the aircraft. After completing the circuits, he was informed that the medivac flight would need to be delayed due to a delay with the patient.

The pilot indicated that these types of delays were normal for RFDS operations and that, while broken activity schedules could increase fatigue, he was aware of the hazard and monitored his fatigue accordingly. The pilot reported that, at the time of the incident flight, his personal fatigue level was acceptable for the work required.

The flight was operated with a single pilot, in line with RFDS practice. As such, the pilot in command conducted all communication, aircraft preparation and surface navigation tasks before and during taxi. The nature of the service provided by the RFDS frequently required operation into temporary or makeshift aircraft landing areas that had poor or no lighting. In response, the RFDS had equipped their fleet of B200 aircraft, including FDL, with upgraded LED landing and taxi lights that provide a significant increase in illumination (Figure 4).

Figure 4: RFDS Beech B200 landing and taxi lights

The nose gear of a RFDS Beech B200 fitted with LED lights for landing (outer) and taxi (centre). Source: Royal Flying Doctors Service

The pilot advised that he was satisfied with the light available to him during taxi and take-off. The operator’s line-up checklist included a check that the aircraft landing lights were on immediately prior to entering the runway, but did not include a check that the runway lights were on.

Previous occurrences

A review of previous ATSB investigations found the following similar occurrences where an aircraft took-off without runway lighting activated:

- On 12 March 2008, an Airbus A320-200 departed from Launceston Airport runway 32L without the runway lights activated (ATSB investigation AO-2008-020). The investigation found that the flight crew did not activate the pilot activated lighting at Launceston prior to departure and did not detect that airport lighting was not on during the taxi and take-off. The report also identified seven other occurrences that were not investigated, between 1988 and 2008, where an aircraft had taken off at night without the runway lights being activated.

- On 30 November 2011, an Emirates Airlines Boeing 777-31H/ER, departed from Melbourne Airport runway 16 without the runway lights activated (ATSB investigation AO-2011-161). The investigation found that the aerodrome controller did not activate runway 16 lighting in response to a requested change in runway from the flight crew. In addition, the report identified that the illumination provided by the aircraft lights was sufficient to be mistaken as low intensity runway lighting.

- On 16 and 17 May 2012, three aircraft departed from Gladstone Airport without the runway lights being activated (ATSB investigation AO-2012-069). The investigation found that the crews had not activated the pilot activated lighting prior to departure. The report identified that all pilots commented that the aircraft lights provided a substantial amount of illumination during the taxi and take-off roll and that the flashing warning lights (on the primary windsock) were hard to see due to other environmental lighting.

- On 19 and 28 August 2016, a JetGo Australia Embraer EMB-135LR, departed from Tamworth Airport without the runway lights activated (ATSB investigation AO-2016-108). The investigation found that the flight crew did not activate the pilot activated lighting on runway 30R at Tamworth before beginning take-off. In addition, the report identified that available lighting from the aircraft taxi and landing lights, a lack of crew expectation, a short taxi with high workload, and no assigned role or procedure to check for runway lighting resulted in the crew not detecting the lack of runway lights.

Safety analysis

Air traffic control

The controller described his use of the ‘LIGHTS’ memory prompt in INTAS as a passive risk control measure. The memory prompt was left on screen for the entire period from last light to first light, independent of the status of the runway lights (on or off). In addition, the workflow in INTAS for a departing aircraft did not require the controller to pass the flight progress strip of this flight through the ‘LIGHTS’ prompt when it was moved from the taxiway to the runway.

Continuously displayed prompts, which do not require action or provide a barrier to other actions, may lead to user de-sensitisation. Over time, this may have resulted in the controller not processing the ‘LIGHTS’ prompt in his workflow.

In addition to the ‘LIGHTS’ prompt, the controller indicated that it was his normal practice to conduct a visual scan of the INTAS display and airfield before clearing an aircraft to enter the runway. The controller recalled completing the scan on this occasion, but did not notice that the runway lights were not on and subsequently did not take action to activate the lights. The controller also stated his expectation that the pilot would notify them of any issue with the runway lights.

Pilot

The period of taxi is a time of high workload for a pilot, particularly in a single pilot cockpit, where they are required to divide their attention in order to perform several tasks. During this time, the pilot of FDL received notification from the cabin medical crew indicating the cabin was not yet secure for take-off. This led to the pilot’s request to ATC for an extended backtrack on runway 15. The pilot’s additional communications with the medical crew and ATC, while taxiing the aircraft, placed further demands on his attentional resources, resulting in an increased workload while in the runway environment.

The pilot’s view from the cockpit of FDL, once aligned on the runway for backtrack and then take‑off, would have included light from the strong aircraft landing lights reflected in the inactive HIRL. The presence of this reflected light along with that of several other light sources from a generally well-lit aerodrome would have resulted in significant light being presented to the pilot when conducting his visual scan.

This reflected and environmental light, along with the absence of a specific check for runway lights resulted in the pilot not realising that the runway lights were not active prior to commencing his take-off. When FDL rotated[7] for take-off the aircraft lighting was directed away from the runway lighting, and the loss of the reflection provided an illusion to the pilot that the runway lighting extinguished as soon as the aircraft became airborne.

A review of the sequence and timing of clearances requested and given to the pilot showed that the aircraft was not required to stop at any point before take-off. The pilot noted that not stopping at the holding point before entering the runway removed an opportunity to visually check the runway without the landing lights shining on it. He recounted that the increased workload involved in securing the aircraft for take-off should have prompted him to pause and re-assess his environment before initiating take-off. However, while certainly good practice, an additional pause when lined up would likely have been ineffective due to the combined expectation that the lights would be on and the presence of the light reflected in the HIRL.

Findings

These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

- The air traffic controller inadvertently did not activate the runway lighting controls prior to VH‑FDL entering runway 15 for take-off. Subsequently, the aircraft took-off without the lights active.

- The increased cockpit workload combined with the reflected and environmental lighting resulted in the pilot of VH-FDL being unaware that runway lights were not on before commencing take-off.

Safety message

Runway lighting serves many important functions for a departing aircraft. For example, it provides:

- directional guidance during the take-off roll

- an indication of the location of the end of the runway

- necessary guidance for approach and landing if required due to an emergency shortly after take-off.

This event demonstrates the importance of implementing robust processes to ensure that routine tasks are always carried out. In particular, it highlights the hazards of skill based human error and expectation bias when performing routine tasks such as activation and checking of runway lighting.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2018

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________

- Eastern Standard Time (EST): Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) + 10 hours.

- Electronic flight progress strip: contains abbreviated aircraft details, current location and control instructions as an awareness tool for the controller

- Integrated Tower Automation Suite (INTAS): an electronic system provided by Airservices Australia for use by air traffic controllers to coordinate and monitor aircraft movement and airfield functions.

- Automatic Terminal Information Service (ATIS): The provision of current, routine information, including weather, to arriving and departing aircraft by means of continuous and repetitive broadcast.

- FEW: Abbreviated reporting unit of cloud amount in visible sky area indicating cloud is covering one to two eighths of total area visible to celestial horizon. This may also be reported as 1-2 OKTA.

- SCT: Abbreviated reporting unit of cloud amount in visible sky area indicating cloud is covering three to four eighths of total area visible to celestial horizon. This may also be reported as 3-4 OKTA.

- Rotation: the positive, nose-up, movement of an aircraft about the lateral (pitch) axis immediately before becoming airborne.