Overview of the investigation

The occurrence

On the afternoon of 14 November 2022, a Boeing 737-800 aircraft (B737), registered VH-IWQ was being operated by Virgin Australia on a passenger air transport flight between Melbourne, Victoria and Sydney, New South Wales. The flight from Melbourne had been uneventful and the flight crew of the B737 were given a clearance by the aerodrome controller (ADC)[1] to land on runway 25 at Sydney and vacate the runway at taxiway Yankee. After vacating the runway, the flight crew contacted the surface movement controller east (SMCE)[2] and were issued a clearance to taxi to their assigned parking bay on the domestic apron via taxiway Golf, and to cross runway 34 left (34L). The SMCE deactivated the taxiway stop bar[3] for the B737 to cross the runway.

At the time the clearance was issued for the B737 to cross the runway, an Airbus A380-841 (A380) aircraft, registered 9V‑SKQ and operated by Singapore Airlines, had just commenced its take-off on runway 34L and was accelerating through a groundspeed of about 40 kt. The B737 was on taxiway Golf and about 300 m from runway 34L when its flight crew saw the A380 on initial climb. They remarked to each other that this was unusual and thought they had been instructed to cross runway 34L ahead. They contacted the SMCE and received confirmation they were clear to cross the runway and taxied to their parking bay. The B737 did not infringe on the 34L runway strip and there was no runway incursion.

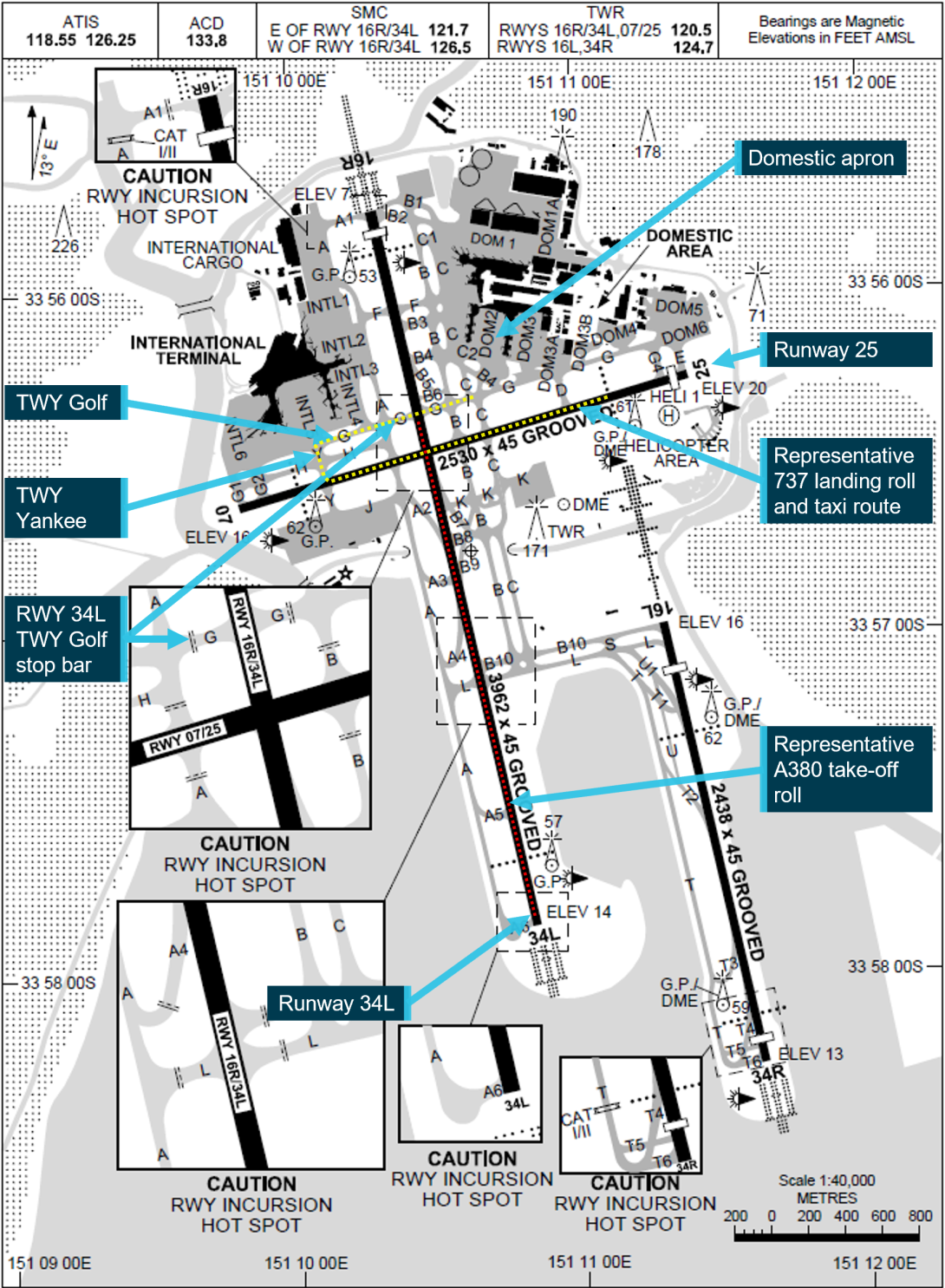

Figure 1 depicts the relative locations between runways 25 and 34L, representative ground tracks for the B737 and A380 together with the location of taxiways Yankee and Golf.

Figure 1: Extract from Sydney Airport aerodrome chart with runway (RWY) orientation and taxiway (TWY) layout

Source: Airservices Australia, annotated by the ATSB

Runway and taxiing operations

Strong westerly winds prevailed during the afternoon, with runway 25 being used as the duty runway for both arriving and departing aircraft. For aircraft requiring the use of a longer runway, 34L was available on request but was deactivated when not operationally required.

With runway 25 being used for arrivals, flight crews of landing domestic jet aircraft were typically required to vacate via taxiway Yankee or if operationally required, taxiway Alpha. The flight crew were then to contact the SMCE, who would issue the taxi clearance to the domestic apron, including the clearance to cross runway 34L.

Similarly, the surface movement controller west (SMCW) was responsible for coordinating taxi clearances for aircraft using the international apron. The SMCW had provided approval for the flight crew of the A380 to push back from their parking bay and issued the clearance to taxi to the runway threshold for 34L.

Activation of runway 34L and take-off of the A380

The ADC had activated runway 34L using the tower control and monitoring system. Soon after, the flight crew of the taxiing A380 had called ready for take-off. With the activation of the runway, the responsibility for separating aircraft and vehicles using that runway transferred to the ADC, including approving requests to cross or enter the active runway.

The SMCE and SMCW were alerted to the runway activation by notification chimes at their controller positions, which required their acknowledgement and insertion of a ‘34L ACTIVE’ strip in their flight progress strip board.[4] The SMCW and SMCE in turn used their hotline to the ADC to acknowledge the changed status of the runway and provide relevant details for aircraft or vehicles operating on that part of the aerodrome’s movement area. When the SMCE acknowledged the runway activation and placed the relevant status strip into their flight progress strip board, they requested (and were issued) clearance from the ADC, for an aircraft under tow to cross runway 34L.

After activating the runway, the ADC instructed the flight crew of the A380 to line-up and hold position. Soon after, the B737 flight crew were transferred to the tower frequency and established contact with the ADC. About a minute later, the ADC issued the B737 flight crew a landing clearance and passed information about the A380, which was lining-up on the crossing runway to hold position. The ADC issued the A380 flight crew their clearance to take-off as the B737 passed through 34L during its landing roll.

After landing and vacating the runway, the B737 flight crew transferred to the SMCE frequency. The SMCE subsequently issued the B737 flight crew their taxiing instructions and clearance to cross runway 34L, without coordinating the crossing of the active runway with the ADC.

Sighting limitations

The B737 operator required its flight crews to scan the runway approach path and runway environment prior to entering any runway, to identify potential traffic that could conflict with their safe crossing. Flight crew and airside vehicle drivers crossing runway 34L in the vicinity of taxiway Golf had several sighting limitations along the runway to the south, principally due to reprofiling of terrain that had occurred with the construction of General Holmes Drive (which passes under the airport south of taxiway Golf).

The ATSB examined any sighting limitations based on the time a B737 flight crew would have been scanning the runway environment as they approached the taxiway hold position and the performance of the A380 on its take-off roll. The ATSB found that the lower fuselage, wings and landing lights of an A380 would be shielded by terrain during the first part of the take-off roll and not visible to flight crew or vehicle operators approaching runway 34L along taxiway Golf. In addition, the oblique viewing angle of an A380 upper fuselage and tail at the maximum sighting range made it harder to identify aircraft during the early stages of the take-off roll.

Stop bar lighting and procedures

Operating the stop bars and runway guard lighting

The airport’s ground-based infrastructure included runways, taxiways and the associated airfield lighting systems, which were maintained by Sydney Airport Corporation Limited. The intersections of taxiways with runways were equipped with stop bar lighting, runway guard lighting[5] and movement area guidance signs. Those systems were intended to help reduce the incidence of runway incursions.[6]

Local procedures at Sydney required taxiway stop bars to be illuminated at all runway crossing points, irrespective of runway status.[7] Consequently, an air traffic controller was required to deactivate the taxiway’s stop bar for every clearance issued for a runway crossing or entry by taxiing aircraft or authorised vehicles. The responsible controller selected and deselected the taxiway’s stop bar using the airfield ground lighting (AGL) panel.[8] The location of the stop bar at the intersection of taxiway Golf with runway 34L is depicted in Figure 1.

As noted previously, when runway 34L was active, the ADC was responsible for separating aircraft and vehicles, and for operating the stop bars. When runway 34L was inactive and the runway had been released by the ADC, the SMCE in this case was responsible for both deactivating the stop bars and issuing the runway crossing clearance to flight crews of aircraft taxiing to the domestic terminal.

Advanced surface movement guidance and control system

Sydney Airport was equipped with an advanced surface movement guidance and control system (A-SMGCS) that provided tower controllers a surveillance picture of the airport’s surface movement areas. The A‑SMGCS interfaced with several related systems, including the airport surveillance radar, flight data system and AGL systems.

Data was shown on the A-SMGCS controller’s working position display, which included a map of the airport environment (runways, taxiways and apron/ramp), together with the position/identification of aircraft/vehicles and information about the status of the various related systems. The system also had several safety logic functions that included closing/opening a runway, airport configuration, operator role (including control over runways) and runway alerts and warnings. The safety logic detection parameters would activate an alert or warning when detecting a conflict between tracks on the runway. In this instance, a safety alert was not generated due to the B737 not entering the runway strip while the A380 was on its take-off roll.

Manual of Air Traffic Services procedures

The Manual of Air Traffic Services (MATS) procedures required that all runways in use were controlled by the relevant ADC and activation of all stop bars at the holding positions associated with that runway (where installed). The ADC controlling the runway was responsible for issuing clearances to cross or enter the runway and temporarily deactivating the stop bar at that relevant holding position to indicate the traffic may proceed. Stop bars were installed on the runways at Brisbane, Canberra, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney airports.

At Canberra, Melbourne and Brisbane, the stop bars were only activated when the runway was in use. When runways at those airports were not in use, the stop bars were deactivated and the inactive runway did not need to be released to the SMC.[9] This was consistent with the guidance provided in MATS.

For Sydney and Perth airports, stop bars were continuously active irrespective of the runway status. When a runway was not in use, the ADC released the runway to the SMC who was then responsible for authorising flight crews or vehicle drivers to cross/enter the runway and also operated the stop bar lighting system.[10] While this was inconsistent with MATS, Airservices Australia, the airport operators and local users had implemented local procedures to facilitate the activation of stop bars on all runways, irrespective if they were in use and under the control of an ADC.

Operational standards review

Airservices Australia’s Sydney tower unit had been subject to a routine national check and standardisation supervisor review in June 2022, covering the period from completion of the last review in May 2019. The purpose of review was to ensure that the unit was meeting required documentation and operational standards, together with consideration of any local unit procedures that could be considered for national implementation.

The review identified that Sydney tower operated stop bars differently to other airports, including their use when the runway was not being used, when stop bar activation was not required. That finding was not identified to be safety critical but recommended that the process for stop bar operation should be standardised. The actions identified to address the finding included a clarification to MATS that the controller with control of the runway was to have sole ownership of the associated stop bars and that the stop bar procedures for Sydney were to be aligned to the national standardised practice.

The revised procedures were subsequently implemented in March 2024. In addition, in July 2024, the AGL system was updated, enabling the jurisdictional transfer of stop bar operation to the ADC at times the runway was in use and at those times, the stop bars could not be deactivated by the SMC.

Surface movement controller east information

The controller performing SMCE duties at the time of the incident had more than 30 years’ experience and had worked in Sydney Tower for most of that period. The controller was rated for all positions in Sydney Tower and previously held ratings for training, checking and supervising tower operations. They had successfully completed 2 days of their regular scenario based tower simulator training about 10 days prior to the incident and their 6-month proficiency check in August 2022.

The SMCE had signed on for duty at 1320 and felt they were adequately rested and fit for their duty. The controller had occupied 2 other positions (with 30-minute breaks between each position) prior to commencing the SMCE duties. At the time of the incident, the controller had been performing SMCE for about 1 hour 15 minutes and recalled feeling 4-a little tired, less than fresh.[11] The ATSB reviewed the controller’s roster for a 6-week period, however, there was insufficient evidence to suggest that the controller’s performance was affected by fatigue.

The incident flight was the first activation of runway 34L for a departing or arriving aircraft while the controller was in the SMCE position. Prior to this, the SMCE had cleared the flight crew of about 18 landed jet aircraft to taxi to the domestic terminal. These all included a clearance to cross the inactive runway 34L and deselection of the stop bars. This was in addition to the SMCE’s other workload, which included coordinating ground movements for arriving turboprop aircraft, departing aircraft (including approving pushbacks from the parking bay), and other vehicles operating on the airport.

ATSB observations

The ATSB made the following observations regarding the incident:

- When the flight crew of the B737 landed and contacted the SMCE for taxiing instructions and a clearance to their parking bay, the SMCE did not correctly recall the changed status of runway 34L. Subsequently, they deactivated the stop bar and issued a clearance for the B737 to cross the active runway. However, as the runway was active, those actions were the responsibility of the ADC.

- Although the SMCE was using the runway 34L active strip in the flight progress strip board, clearing landed jet aircraft to the domestic apron, deselecting the stop bar lighting in the AGL panel and crossing them through the inactive runway 34L was a repetitive task and familiar in nature. This increased the likelihood that if a change to the runway status was overlooked, it would result in the deactivation of the stop bar lighting and the issuing of an incorrect clearance.

- The design of the AGL panel at the time of the incident enabled the SMCE to deactivate a stop bar of an active runway, for which they did not have responsibility for.

- At the time of publication for this notice, only 5 Australian airports were fitted with stop bars. The procedures for using stop bars on inactive runways varied between these airports.

- The routine use of stop bars on an inactive runway was inconsistent with the procedures indicated in MATS. This influenced the SMCE deactivating the stop bars and issuing the clearance for the B737 flight crew to cross the runway while it was being used for take-off by the A380. Alternately, if the stop bars were only used when the runway was in use, the stop bars would have been activated by the ADC when resuming control for the runway. Even if the SMCE had incorrectly assessed the status of the runway and issued a clearance to cross (what they thought was an inactive runway), the stop bars would have remained illuminated, indicating to the flight crew they could not cross.

Safety action

Procedural changes to the stop bar operation at Sydney Airport and implemented since this incident are as follows:

- If runway 34L is inactive and the ADC has not released the runway to the SMC, the ADC retains stop bar ownership and is required to approve all runway crossings of the inactive runway. The SMC is unable to operate the stop bar lighting controls in the AGL panel.

- If runway 34L is inactive and the ADC has released the runway to the SMC, access for the SMC to operate the stop bars is enabled in the AGL panel when the ADC selects the relevant runway mode. The SMC is responsible for issuing runway crossing clearances and operates the stop bars without requiring coordination with the ADC.

- When runway 34L has been released to the SMC and the ADC takes ownership back, the ADC amends the operating mode in the AGL panel and the SMC is then unable to operate the stop bar lighting controls in the AGL panel. The SMC coordinates runway crossings with the ADC, who operates the stop bars.

- When runway 34L is active, the ADC retains stop bar jurisdiction and the SMC is unable to operate the stop bar controls in the AGL panel. The SMC requests clearances for runway crossings from the ADC, and when the ADC approves the crossing and deselects the stop bar, the SMC issues the clearance for the aircraft or authorised vehicle to cross the runway.

Safety message

Although stop bars were principally introduced to help reduce runway incursions by taxiing aircraft and authorised airside vehicles during periods of low visibility, they are also used effectively at other times to help reduce the risk of an incursion on an active runway. The ATSB also notes that, at Australian airports where stop bar lighting is only activated at times the runway is active, the associated procedure introduces an additional risk control by removing the coupling between an SMC’s deactivation of stop bars and their issuing of clearances to cross the inactive runway. This reduces the potential for an SMC to deactivate stop bars and issue an incorrect clearance to cross an active runway, with taxiing flight crew and vehicle drivers required to stop at all illuminated stop bars.

Reasons for the discontinuation

Based on a review of the available evidence and the implementation of safety action by Airservices Australia and Sydney Airport Corporation Limited, the ATSB considered it was unlikely that further investigation would identify any systemic safety issues or important safety lessons.

The ATSB strives to use its limited resources for maximum safety benefit, and considers that in this case, the change to stop bar procedures at Sydney Airport and the change to the airfield ground lighting system has likely reduced the risk of a similar incident occurring. Consequently, the ATSB discontinued the investigation.

[1] The function of aerodrome control for the purpose of aircraft taking-off, landing and transiting the airspace associated with the control zone was provided by air traffic controllers located in the airport’s control tower. At Sydney Airport, there was provision for several aerodrome control positions, depending on the number of runways in use and any additional coordination that was required for arriving and departing aircraft.

[2] The function of airport surface movement control was provided by an air traffic controller located in the airport’s control tower. At Sydney Airport, there were 2 surface movement control positions (east and west). The surface movement controller coordinated the ground movement of aircraft and vehicles.

[3] When activated, the stop bars comprise a row of red lights inset into the surface of the taxiway, at an angle of 90° to the taxiway centreline. The inset lighting was augmented with a red above ground light either side of the taxiway, abeam the stop bar position. Aircraft or authorised vehicles must not cross the stop bars without both an air traffic control clearance and the red stop bar lights being extinguished.

[4] The flight progress strip board formed part of the controller’s scan when issuing clearances to cross inactive runways.

[5] Runway guard lighting comprised pairs of above ground flashing amber lights on each side of the taxiway, which continuously flashed to indicate a runway was ahead. Each amber light in the pair flashed alternately so that one light in each pair was always illuminated. Runway guard lighting installations are also known as ‘wig wags’.

[6] Stop bar and runway guard lighting was initially designed to reduce the risk of runway incursions during periods of low visibility. Those lighting systems are also used more generally to help mitigate the risk of runway incursions that could occur at other times.

[7] When not being used operationally, a runway could be inactivated and responsibility for aircraft and vehicles using that part of the movement area transferred to the surface movement controllers.

[8] The airfield ground lighting system was part of the airport’s operating infrastructure, which was provided/maintained by Sydney Airport Corporation Limited.

[9] At Canberra airport, stop bars were activated when runways were closed by NOTAM. In addition, when the tower was closed overnight, the stop bars were deactivated and flight crews were responsible for their operations at the uncontrolled aerodrome.

[10] At Perth and Sydney airports, stop bars were also activated when runways were closed by NOTAM.

[11] The score is based on the Samn-Perelli 7-point fatigue scale, where 1 indicates fully alert and 7 indicates completely exhausted.