Investigation summary

What happened

On the evening of 13 June 2024, a Batik Air Boeing 737-800, registered PK-LDK, departed I Gusti Ngurah Rai (Denpasar) International Airport, Bali, Indonesia for the inaugural passenger transport flight of a new service to Canberra, Australian Capital Territory. While en route, the flight crew noted that the estimated time of arrival into Canberra was prior to 0600 local time on 14 June, when Canberra Tower and Approach air traffic control began providing services for the day. The crew elected to proceed without any delays and prepared for an arrival without those air traffic control services, using the Canberra Airport common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF).

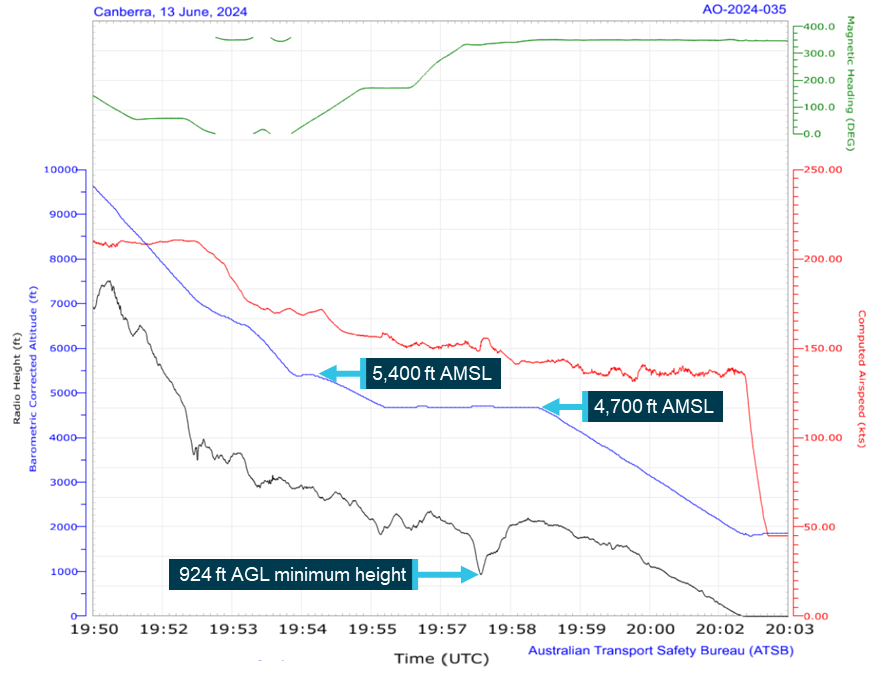

As the aircraft was descending toward uncontrolled airspace and tracking direct to Canberra along the flight path cleared by air traffic control, the crew deviated from the cleared track by commencing the AVBEG 5A standard arrival route (STAR). The duty air traffic controller intervened and provided altitude instructions to maintain separation from an en route restricted area. This intervention resulted in the aircraft becoming higher than the desired descent profile and the crew decided to use the holding pattern at the approach waypoint of MOMBI to reduce altitude. While flying the holding pattern at MOMBI, the aircraft was descended to 4,700 ft above mean sea level (AMSL), significantly below the holding pattern minimum safe altitude of 5,600 ft AMSL. The aircraft’s recorded radio height subsequently reduced to a minimum of 924 ft above ground level before the approach was recommenced from 4,700 ft AMSL, below the 5,400 ft AMSL minimum altitude for that segment of the approach.

The Canberra Approach controller who took over management of the airspace while the aircraft was in the holding pattern identified that the aircraft was operating below the minimum altitude, contacted the crew to provide a safety alert and advised the crew to contact Canberra Tower. The approach continued using controlled airspace procedures and the aircraft landed shortly after without further incident.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that the MOMBI holding pattern was not correctly flown by the crew and resulted in the aircraft descending significantly below the minimum safe altitude. The Canberra CTAF was also not selected by the crew, and the appropriate radio broadcasts were not made. This prevented the crew from receiving the oncoming Canberra tower controller's safety alerts, being able to illuminate the runway lights and increased the risk of conflict with other traffic.

Prior to commencing the approach, when the crew deviated from the cleared track to Canberra by commencing the AVBEG 5A STAR, the air traffic controller did not advise them of the deviation or provide a safety alert. Instead, the controller provided instructions that contributed to the crew becoming confused regarding the airspace classification for the arrival and approach.

The Melbourne Centre controller providing the flight information service for the aircraft was not, and was not required to be, aware of the holding pattern minimum altitudes. Therefore, the controller did not issue a safety alert when the aircraft descended below the minimum safe altitude.

The ATSB also found that Batik Air's change management processes were not effective at fully identifying and mitigating the risks associated with the commencement of the Denpasar to Canberra route. Batik Air also did not ensure that the crew had completed all CTAF training prior to them operating flights into Australia where the use of these procedures could be required.

The investigation also determined that during a 2022 review of Canberra runway 35 instrument landing system approaches, an obstacle evaluation error led to Airservices Australia increasing the MOMBI holding pattern minimum altitude from 5,100 ft to 5,600 ft. This increase resulted in a transition from the holding pattern to the approach glideslope that increased the risk of unstable approaches and sudden pitch ups. After conducting a revalidation test flight of the holding pattern minimum altitude increase, the Civil Aviation Safety Authority advised Airservices Australia that the increased minimum altitude did not provide an appropriate transition to the approach glideslope and recommended modifications to the holding pattern design. Despite Airservices Australia receiving this advice, no changes were made, and the increased holding pattern minimum altitude was maintained.

What has been done as a result

Following the incident, Batik Air has implemented several proactive safety actions including:

- Revising the Canberra Airport Briefing document to include detailed information on Canberra air traffic control hours, CTAF procedures, holding requirements and guidance for adherence to lowest safe altitude requirements.

- Issuing internal notices to flight crew highlighting the importance of a comprehensive approach briefing, adherence to air traffic control instructions and altitude awareness. These notices also provided information on CTAF and traffic information by aircraft (TIBA) procedures and highlighted the additional risks and absent protections when operating in uncontrolled airspace. Batik Air also disseminated details of the incident to all flight crew and conducted a special flight crew briefing with event details and lessons.

- Completing practical and theoretical CTAF training for all flight crew assigned to Australian operations and incorporating this training into its annual training program.

- Issuing an internal notice highlighting the mandatory Risk Management Review (RMR) process for all new routes and other significant operational changes. This notice intends to ensure comprehensive hazard identification, detailed risk assessments and an evaluation of the need for route proving flights or additional crew familiarisation.

- Adjusting the flight schedule for the Denpasar to Canberra flight to ensure that early arrivals occur during Canberra Tower and Approach air traffic control operating hours.

In December 2024, Airservices Australia reassessed the MOMBI holding pattern and reduced the minimum holding altitude back to 5,100 ft.

Safety message

This incident underlines the need for operators to ensure that they have comprehensive and effective change management processes in place to identify all foreseeable risks relevant to a new route and implement appropriate mitigations to ensure the safe operation of these routes. In this case, the unfamiliar operating environment included the potential for operations using a CTAF, an uncommon operating procedure for non‑Australian operators and crews. Comprehensive and regular crew training is vital in ensuring that crews can effectively manage the risks inherent in the use of unusual procedures.

Additionally, the investigation highlights the importance of suitably designed and appropriate instrument flight procedures for safe air transport operations. In this case, the error made in the holding pattern design was not identified before it was published and while the error did not contribute to this occurrence, it introduced the potential for an unstable approach and/or a sudden pitch up risk to flight crews using the procedure.

The occurrence

On the evening of 13 June 2024, a Batik Air Boeing 737-800, registered PK-LDK, departed I Gusti Ngurah Rai (Denpasar) International Airport, Bali, Indonesia for the inaugural passenger transport flight of a new service to Canberra, Australian Capital Territory. The flight was operating with an enlarged flight crew, the captain was acting as pilot flying, the first officer was acting as pilot monitoring[1] and a second captain was occupying the flight deck jump seat.[2]

As the aircraft climbed to the cruising level of flight level 350,[3] the crew input forecast en route winds, which included strong tailwinds, into the aircraft’s flight management system. The crew noted that the estimated time of arrival into Canberra was prior to 0600 local time on 14 June, when Canberra Tower and Approach air traffic control began providing services for the day (see the section titled Canberra Airport and airspace). The crew elected to continue to Canberra without any en route delays and prepared for an arrival without those air traffic control services, using the Canberra Airport common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF).

As the aircraft descended towards Canberra in darkness, the flight was cleared by air traffic control (ATC) to track via the waypoint AVBEG direct to Canberra Airport and to descend to FL 120. During the descent, the crew prepared to conduct the AVBEG 5A standard arrival route (STAR) (see the section titled AVBEG 5A standard arrival route and restricted areas)but did not make a request to track via the STAR to the Melbourne Centre air traffic controller managing the airspace.

At 0541 local time, as the aircraft approached AVBEG, ATC cleared the crew to leave controlled airspace descending. The aircraft crossed AVBEG while descending below FL 205 and commenced tracking via the AVBEG 5A STAR.

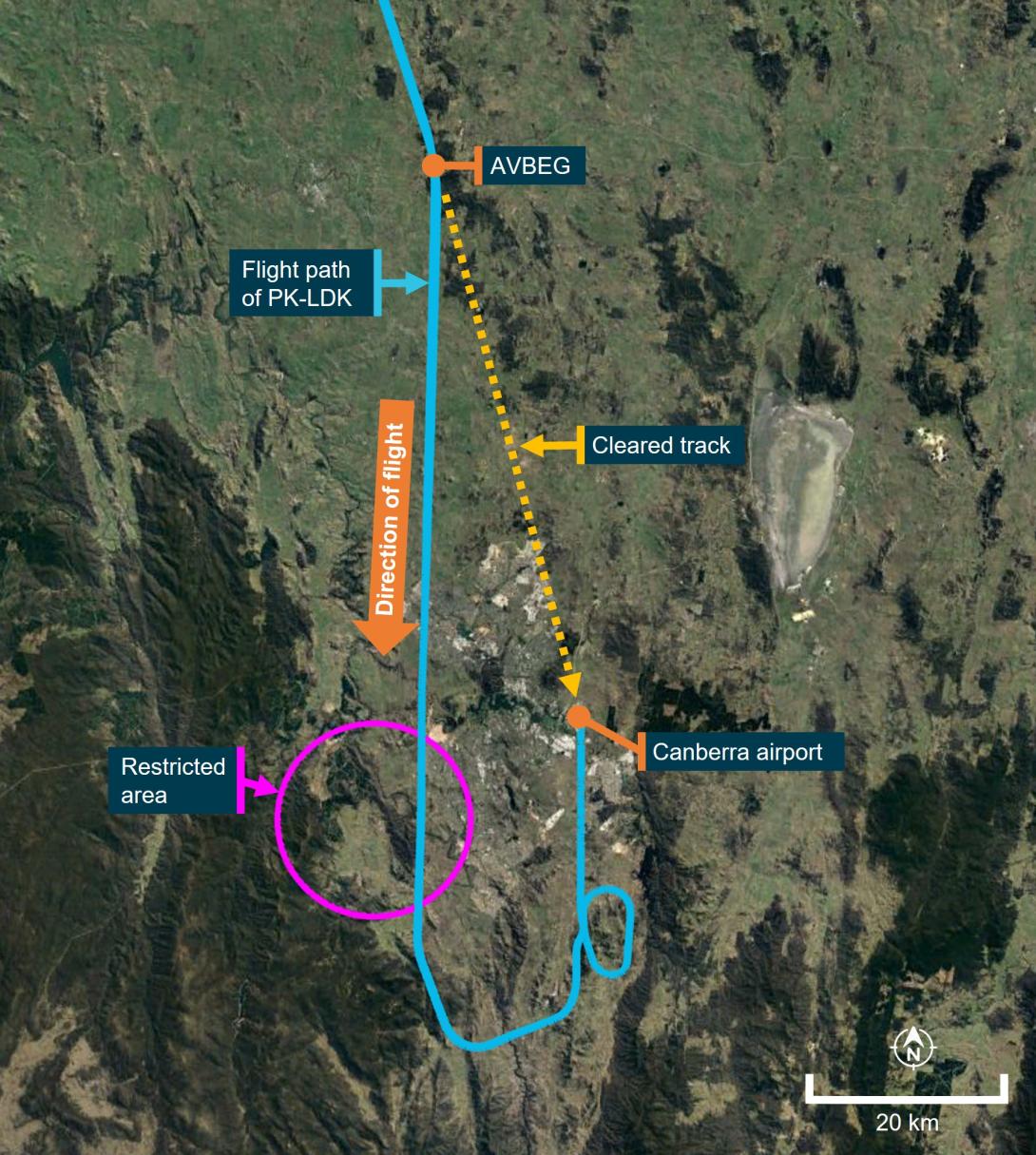

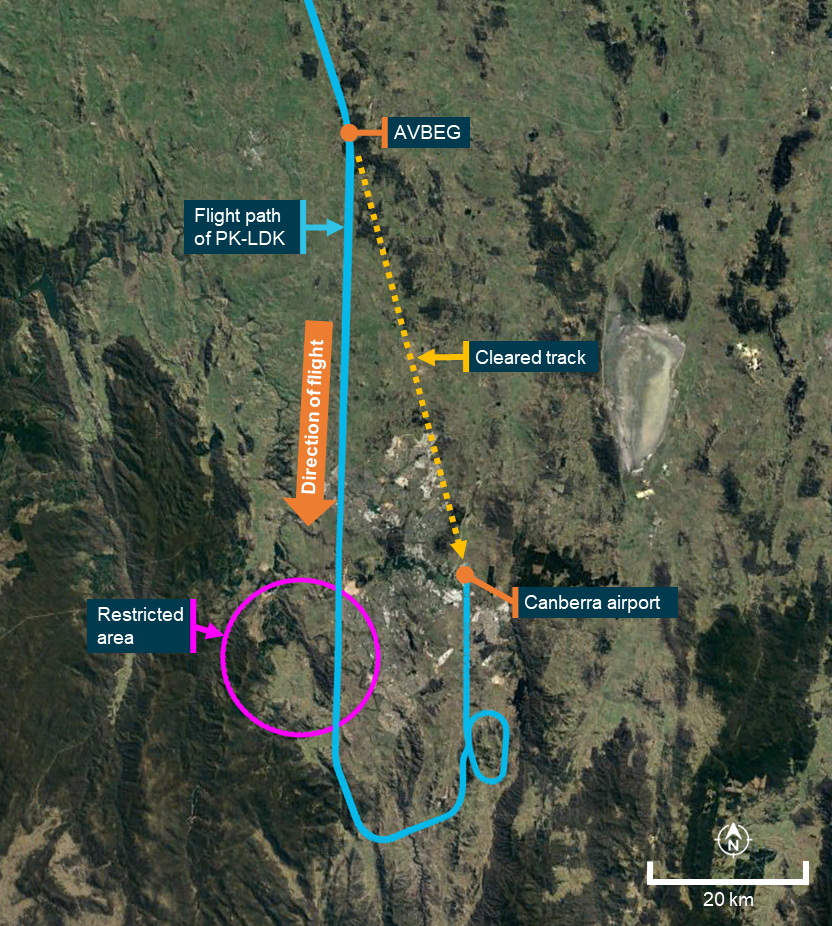

At 0543, the controller managing the airspace handed over management of the airspace to a controller commencing work. This oncoming controller identified that the Batik Air flight was deviating from the cleared track (direct to Canberra) presented in the ATC system while still in controlled airspace. The oncoming controller was unsure if the aircraft was deviating from its clearance or if it had been provided the clearance by the outgoing controller and that clearance had not been entered into the ATC system. The controller also noted that the aircraft was descending toward an active restricted area (Figure 1).

The controller did not query the crew’s deviation or provide a safety alert (see the section titled Safety alerts) but instead asked the crew if they were going to remain clear of the restricted area 17 NM to the south of their position. The crew advised the controller that they were tracking via the AVBEG 5A STAR. The controller acknowledged the tracking advice and instructed the crew to maintain 10,000 ft above mean sea level (AMSL) to remain above the restricted area. After receiving this instruction, the crew became uncertain as to whether the aircraft would be operating within, or outside of, controlled airspace during the STAR and approach.

Figure 1: Overview of the descent

Source: Google Earth, recorded flight data, Airservices Australia and ATSB

The crew levelled the aircraft at 10,000 ft AMSL with the autopilot engaged and the aircraft passed over the restricted airspace. As was required by ATC procedures, the controller waited until the aircraft was observed to be more than 2.5 NM past the restricted area before instructing the crew to continue the descent to leave controlled airspace. The crew responded by advising that they would descend and continue tracking via the STAR. At about this time, the crew noted that the aircraft was about 1,300 ft above the desired descent profile for the arrival.

At 0551, the crew requested confirmation from ATC that they had clearance to conduct the instrument landing system (ILS) approach to runway 35 at Canberra. The controller responded by advising that the Canberra control tower was closed and that CTAF procedures applied for that airspace. At 0551:38, the aircraft descended below 8,500 ft AMSL, outside controlled airspace (into class G airspace).

As the aircraft was higher than the desired flightpath, the captain decided to conduct a holding pattern at the approach waypoint of MOMBI to reduce altitude and the first officer requested ATC clearance to hold at MOMBI. The controller responded by providing traffic information for the MOMBI holding pattern. At 0552:56, the crew again requested confirmation that they had clearance to conduct the ILS approach and the controller responded by advising that clearance was not required, the crew were now in class G (non-controlled) airspace and that the crew must broadcast their intentions on the Canberra CTAF.

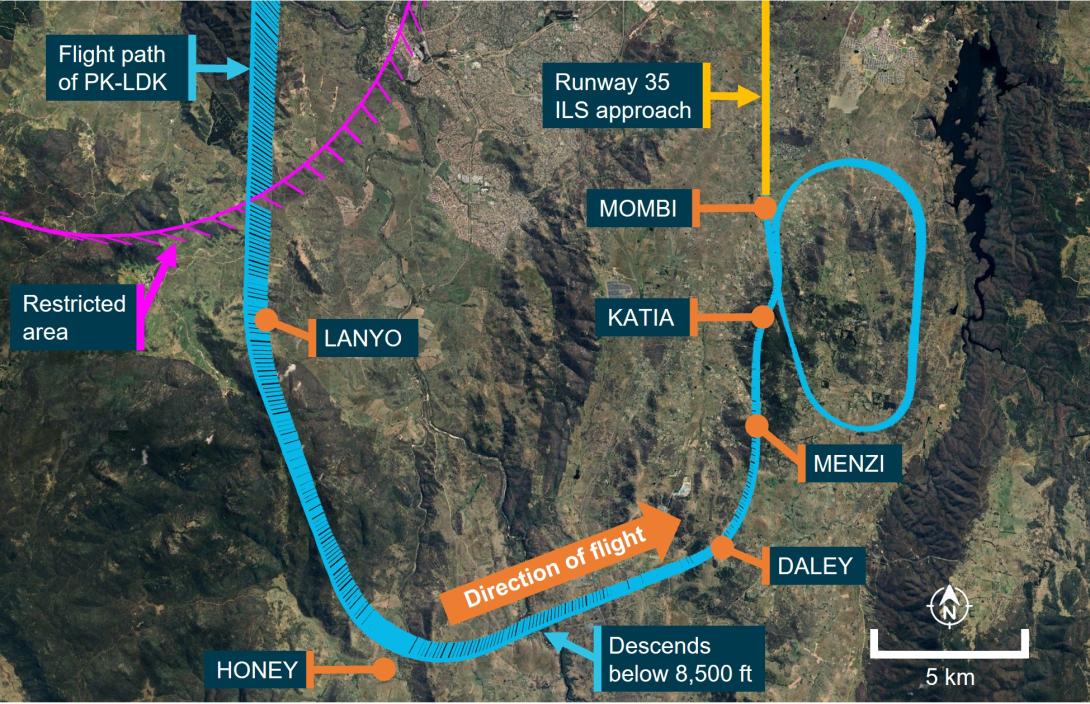

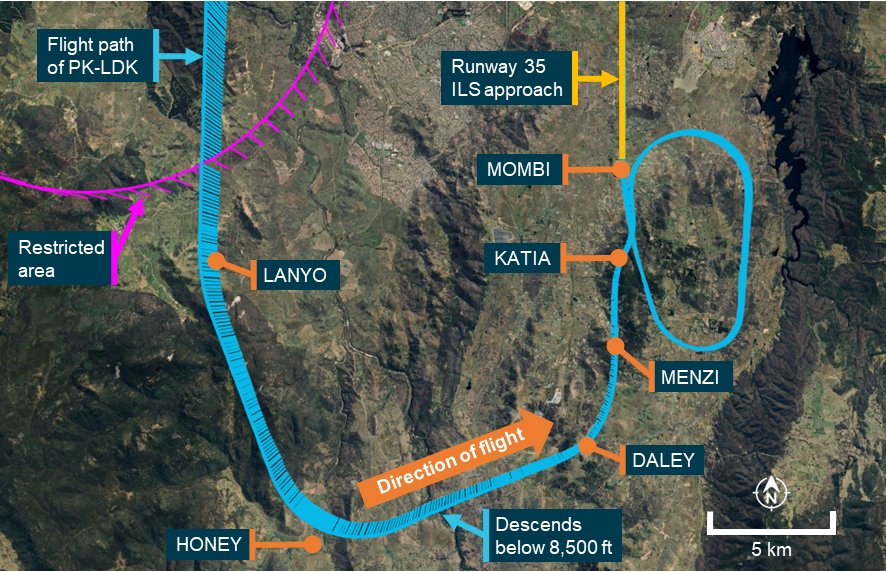

At 0553:10, the aircraft passed the ILS initial approach fix waypoint MENZI (Figure 2) while descending below 6,720 ft AMSL and soon after, made another request to hold at MOMBI. The controller provided traffic information for the hold and requested that the crew make a right‑hand orbit to remain clear of the restricted airspace, now to the west of the aircraft.

Source: Google Earth, recorded flight data, Airservices Australia and the ATSB

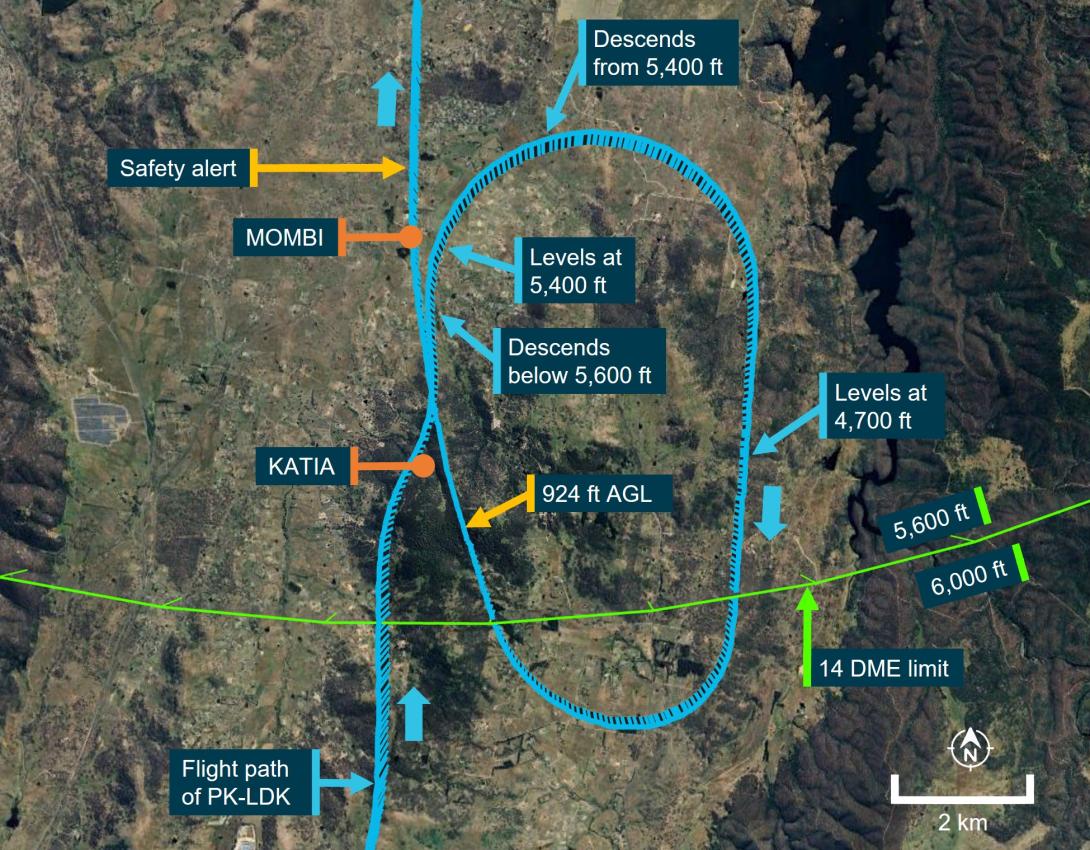

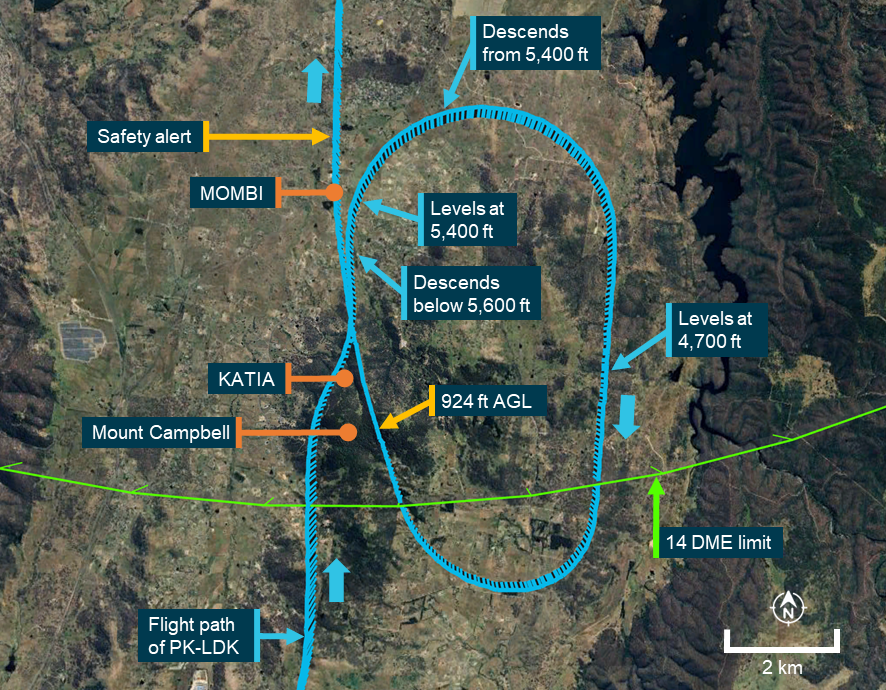

As the aircraft approached MOMBI, the captain entered 5,400 ft AMSL (the approach’s minimum safe altitude before intercepting the ILS glideslope) into the autopilot mode control panel (MCP) and at 0554:15, the aircraft descended below the minimum holding altitude of 5,600 ft AMSL (see the section titled Instrument landing system approach) before levelling at 5,400 ft AMSL.

The captain then used the heading select function to make a right turn to a heading of 170°[4] and the aircraft commenced turning prior to crossing MOMBI. At 0554:30, the aircraft passed MOMBI at a speed of 172 kt (2 kt above the maximum speed for the 5,600 ft AMSL minimum holding altitude).

The captain then asked the first officer to enter a holding pattern into the aircraft’s flight management system (FMS) at MOMBI. As the aircraft had already passed MOMBI, the waypoint had dropped off the FMS track and the first officer was required to manually re‑enter the waypoint into the FMS planned track. As the turn continued, the speed reduced below 170 kt, the captain selected 4,700 ft AMSL (the crew’s intended MOMBI crossing altitude) on the autopilot MCP and the aircraft commenced descending to that altitude. During this time, the Melbourne Centre controller did not identify that the aircraft was operating below the minimum holding altitude of 5,600 ft AMSL.

The aircraft turned to a heading of 170° and continued descending until levelling at 4,700 ft AMSL at 0555:59. As the aircraft tracked south, the oncoming Canberra Approach air traffic controller prepared to take control of the Approach airspace (see the section titled Canberra Tower and Approach) and commenced a handover with the Melbourne Centre controller.

The aircraft continued south and at 0556:25, proceeded beyond the 14 distance measuring equipment (DME) limit for the 5,600 ft AMSL minimum holding altitude. At or before that DME limit, an inbound turn back to MOMBI needed to be commenced, or the minimum holding altitude had to be increased to 6,000 ft AMSL to maintain clearance from higher terrain further to the south. By that time, the first officer had completed re‑entering MOMBI into the FMS and the captain then used the lateral navigation autopilot mode to commence a right turn toward the waypoint.

As the aircraft was turning back toward MOMBI, at 0556:58, the incoming Canberra Approach controller completed their handover with the Melbourne Centre controller and took over the airspace as well as the Melbourne Centre radio frequency that the aircraft was using (this frequency then became a Canberra Approach frequency).

At the same time, the Canberra Tower air traffic controller preparing to commence the tower service observed that the aircraft was operating below the minimum holding altitude and made multiple attempts to contact the crew on the Canberra CTAF. At that time, the crew had not selected the Canberra CTAF and did not receive these broadcasts. As the Tower controller did not have a direct means of communication with the Melbourne Centre controller, the Tower controller contacted a Melbourne Approach air traffic controller to relay their concerns to the Melbourne Centre controller.

The aircraft continued turning toward MOMBI (Figure 3) and as it crossed over the eastern slopes of Mount Campbell at 0557:46, the recorded radio height reduced to a minimum of 924 ft above ground level. The aircraft did not penetrate the ground proximity warning system activation envelope and no alert was generated. At 0558:21, the aircraft rejoined the ILS approach.

Figure 3: Overview of MOMBI hold

Source: Google Earth, recorded flight data, Airservices Australia and the ATSB

The Melbourne Approach controller contacted the Melbourne Centre controller to relay the Canberra Tower controller’s concerns about the aircraft’s altitude and the Melbourne Centre controller responded by advising that the airspace was now being controlled by Canberra Approach.

At about the same time, the Canberra Approach controller also identified that the aircraft was operating below the minimum altitude. The controller contacted the crew and provided a safety alert, querying whether the crew were ‘visual’. The crew responded advising that they were ‘visual with the runway’ and continued the approach. The Approach controller then advised the crew to contact Canberra Tower and the approach continued using controlled airspace procedures. The aircraft landed at 0602 without further incident.

Context

Canberra Airport and airspace

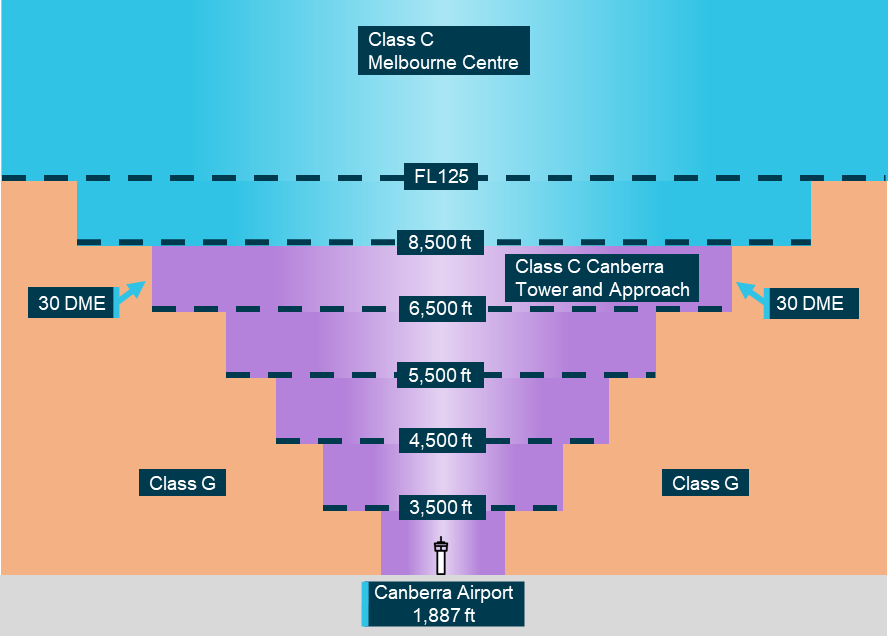

Canberra Tower and Approach

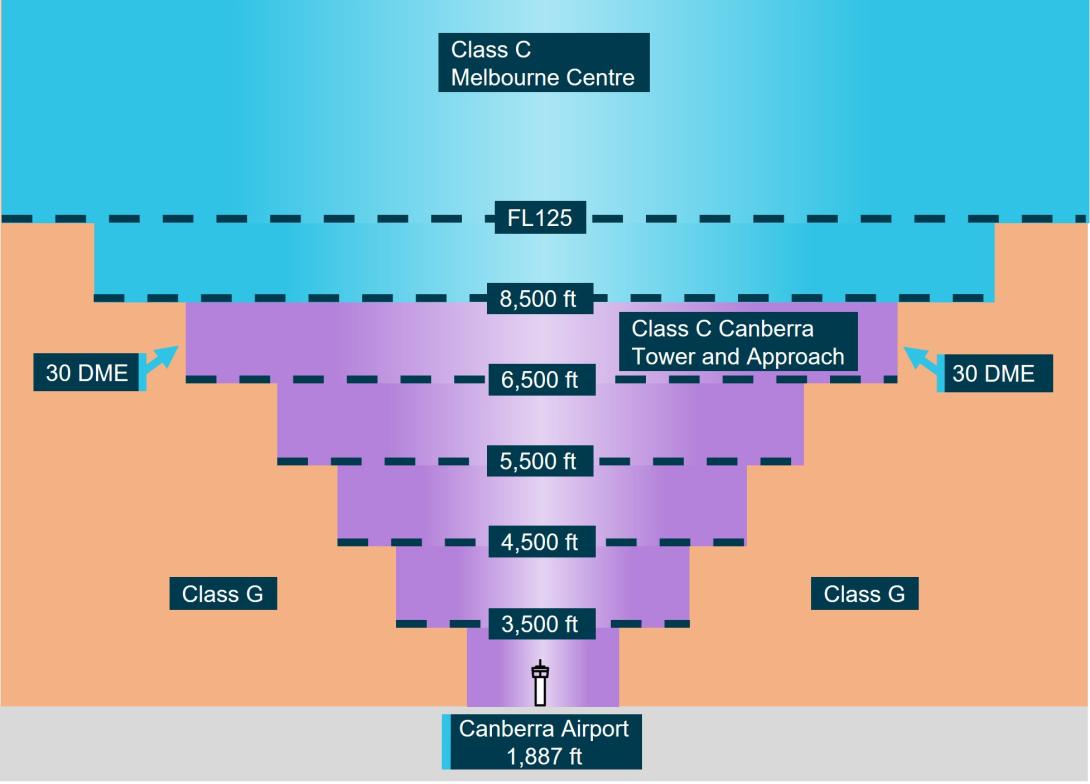

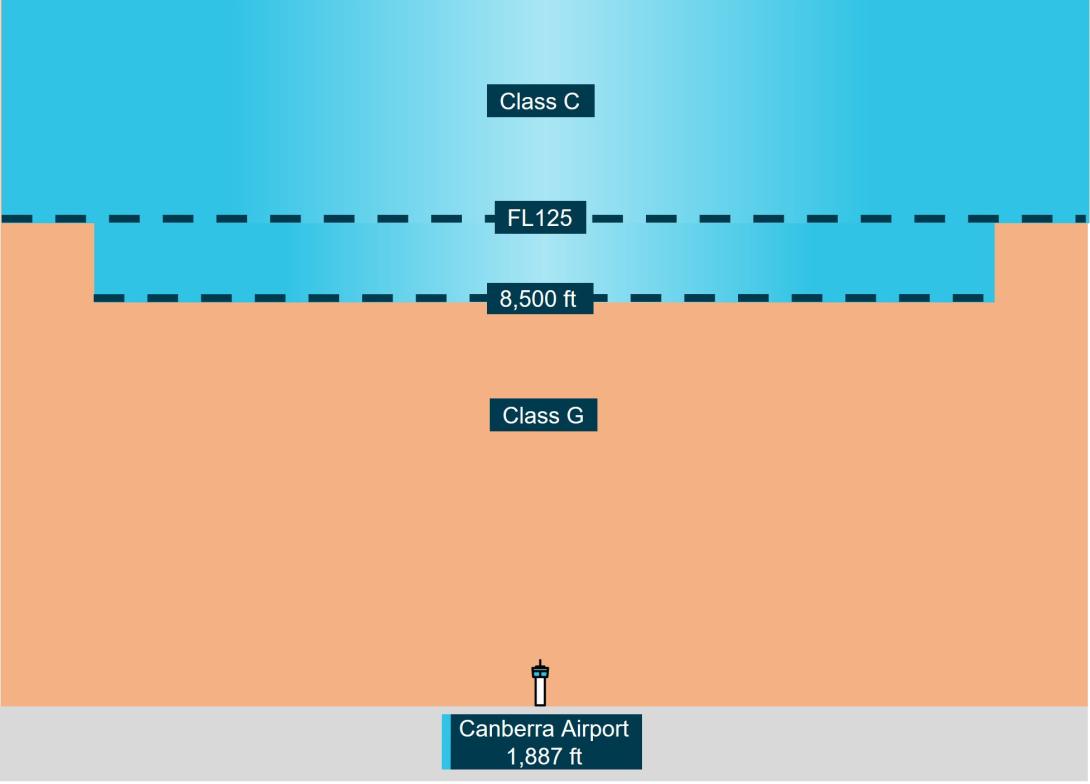

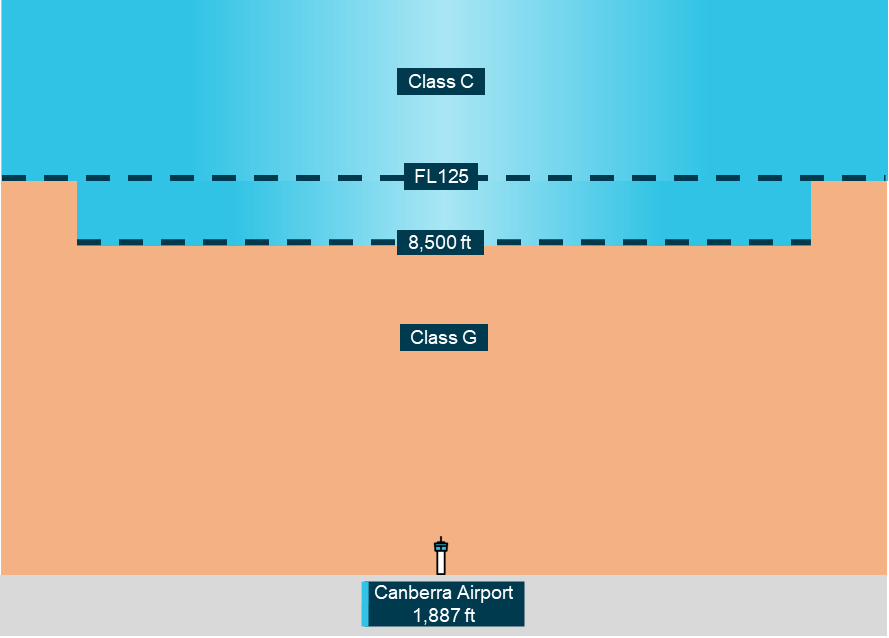

On the day of the incident, the operating hours of controlled airspace associated with Canberra Airport were 0600 to 2300 local time. During these hours, Canberra Airport was within class C airspace, with airspace bases that increased as the airspace fanned out at increasing distances from the airport (Figure 4). The Canberra Tower and Approach air traffic control (ATC) services controlled the class C airspace within 30 DME of Canberra and below 8,500 ft above mean sea level (AMSL). Control services for the airspace above 8,500 ft AMSL were provided by a Melbourne Centre controller at all times during the flight’s descent and approach.

Figure 4: Canberra airspace when Tower and Approach were operating

All altitudes and elevations are above mean sea level. Source: ATSB

Outside of the Canberra Tower and Approach operating hours, the base of the Class C airspace was 8,500 ft AMSL. Below this was class G, non‑controlled airspace (Figure 5). Within class G airspace, flight crews could manoeuvre aircraft as required to position for an approach and were responsible for maintaining adequate terrain clearance. ATC was unable to issue STARs or approach clearances within class G airspace.

Figure 5: Canberra airspace when Tower and Approach were not operating

All altitudes and elevations are above mean sea level. Source: ATSB

Common traffic advisory frequency

When the Canberra Approach and Tower services were not operating, flight crew used a common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF) to make positional radio broadcasts and coordinate self‑separation with other traffic. The CTAF used the same frequency as Canberra Tower (when it was operational).

Pilot‑activated lighting

When Canberra Tower services were not available, the runway and movement area lighting was activated using a pilot-activated lighting system. The lighting was activated by a series of timed transmissions on the CTAF and remained active for 30 minutes.

Aviation rescue firefighting service

Canberra Airport aviation rescue and firefighting services operated only during times advised by NOTAM.[5] On the day of the incident, category 7 rescue and firefighting services[6] were provided from 0540 until 2225. Outside of these hours, no rescue or firefighting service was provided at the airport.

Air traffic control procedures

Manual of air traffic standards

Safety alerts

Airservices Australia’s manual of air traffic standards stated that an air traffic controller must issue a safety alert as soon it is recognised that an aircraft has deviated from an air traffic control clearance and will enter an active restricted area or is operating in unsafe proximity to terrain.[7] Additionally, if possible, a controller was required to provide an alternative clearance.

Track deviation

When observed, air traffic controllers were required to advise flight crews of flight path deviations.[8]

Controller knowledge

When the aircraft descended below the MOMBI holding pattern minimum altitude, the aircraft was operating in non‑controlled airspace. Within that airspace, aircraft operating under the instrument flight rules, such as the incident flight, were only provided with a flight information service.

The Melbourne Centre controller providing the flight information service for this airspace held an area radar control rating. This rating did not require a controller to have knowledge of STAR altitude restrictions and minimum holding altitudes associated with instrument approaches to airports located in non‑controlled airspace, nor did it require controllers be trained to provide specific instructions or corrections to pilots conducting instrument arrivals. The appropriate instrument flight procedure charts were available to the controllers using electronic displays at the control console, but area radar‑rated controllers were not required to know the details of the charts and only required to have awareness of broader lowest safe altitudes within that airspace.

Controllers providing an approach service within controlled airspace (such as the airspace that became active as the aircraft rejoined the approach) were trained to have more detailed knowledge of instrument approach procedures within the airspace. In addition, automated minimum safe altitude warning alerts were generated by the air traffic control system within that airspace.

When the aircraft descended below the minimum safe altitude of the MOMBI holding pattern, the Melbourne Centre controller providing the flight information service was not aware that this had occurred and therefore did not provide a safety alert. The oncoming Canberra Approach and Tower controllers both identified the aircraft operating below the minimum safe altitude. The Tower controller tried several times to contact the crew, but the crew did not have that frequency selected. The Approach controller issued a safety alert to the crew at the earliest available opportunity.

Canberra instrument flight procedures

AVBEG 5A standard arrival route and restricted areas

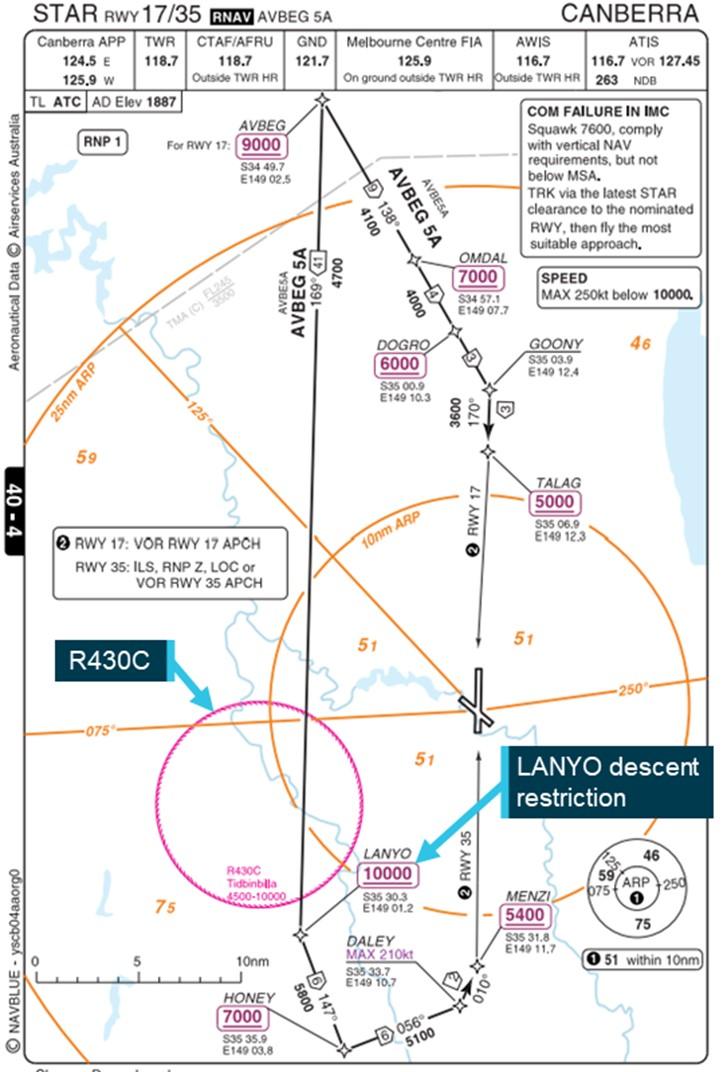

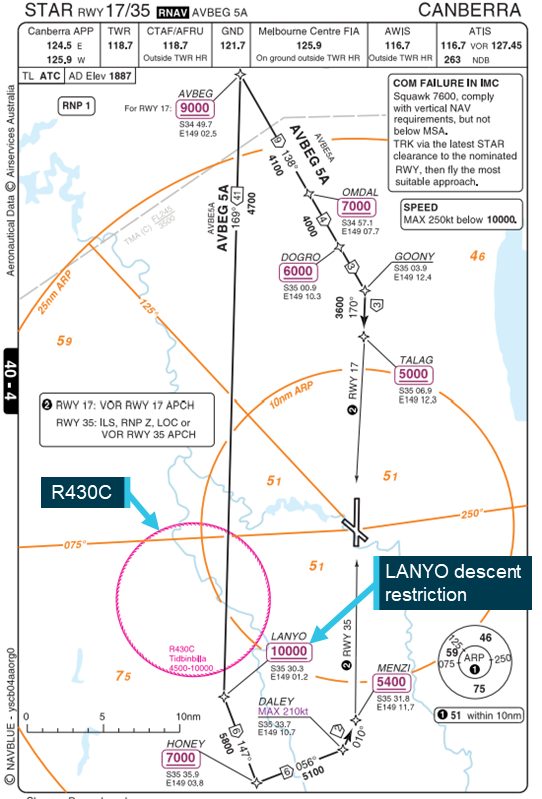

South‑west of Canberra Airport, restricted areas of airspace (R430 A‑C) encompassed the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex at Tidbinbilla. The uppermost of these restricted areas (R430C) had a radius of 10 NM and a ceiling of 10,000 ft AMSL. The AVBEG 5A standard arrival route (STAR) (Figure 6) passed over this restricted area and had a 10,000 ft AMSL descent restriction at the waypoint LANYO which prevented aircraft descending via the STAR from entering the restricted area.

Figure 6: AVBEG 5A standard arrival route

Source: Batik Air and Navblue, annotated by the ATSB

Instrument landing system approach

An instrument landing system (ILS) is an instrument approach procedure that provides lateral (localiser) and vertical (glideslope) position information using angular deviation signals from the localiser antennas (located past the upwind end of the runway) and the glideslope antennas (located approximately 1,000 ft from the runway threshold).

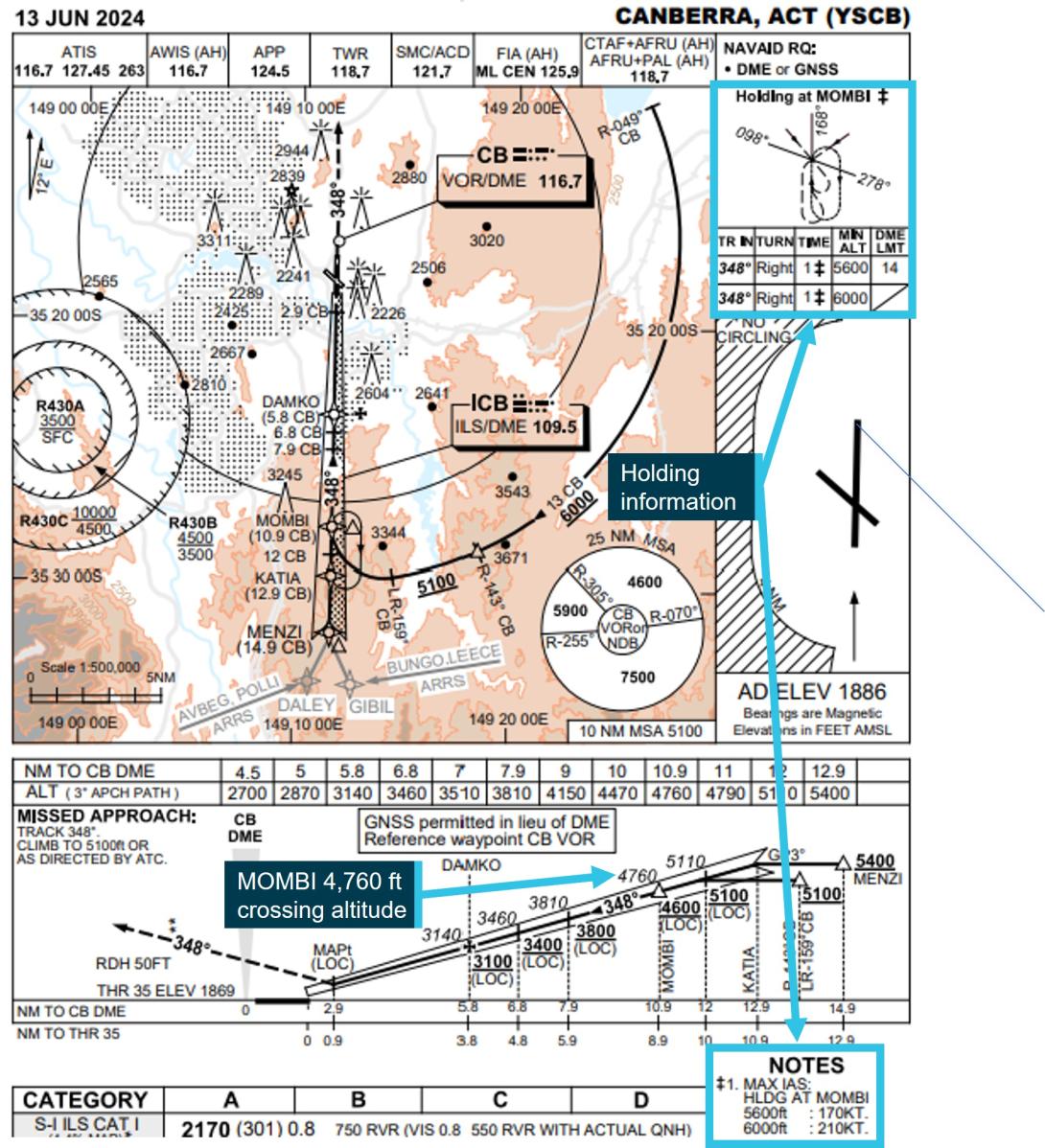

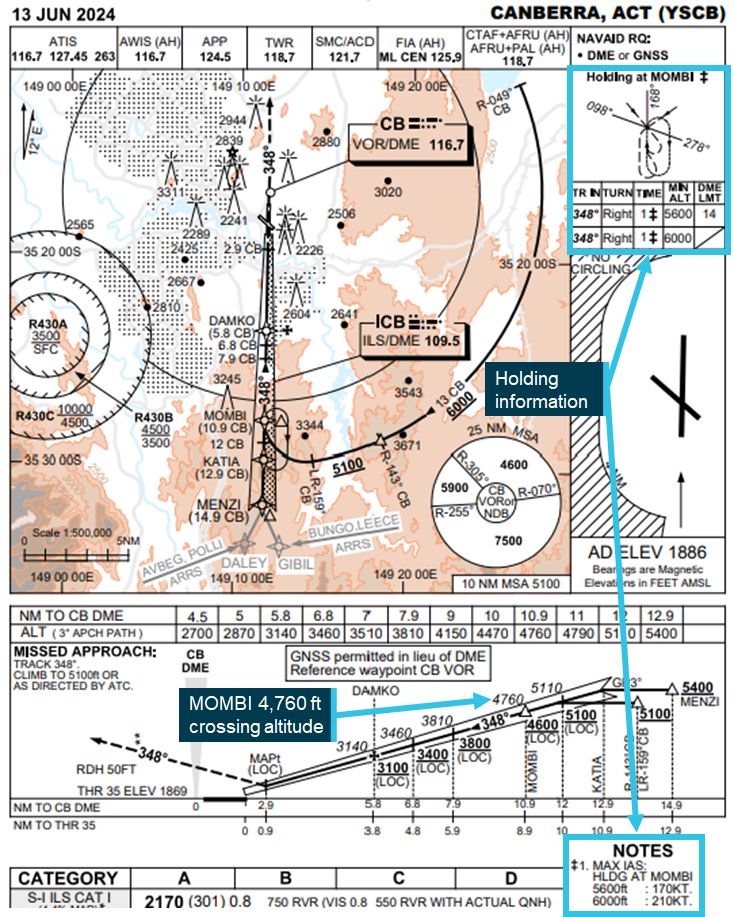

The AVBEG 5A STAR connected with the Canberra runway 35 ILS Y approach at the initial approach fix waypoint MENZI. The minimum crossing height for MENZI was 5,400 ft AMSL. The ILS approach from MENZI included a 3° glidepath to the runway which crossed MENZI at 6,040 ft and the approach waypoint of MOMBI at 4,760 ft AMSL.

The approach included a right turn, 1-minute holding pattern at the approach waypoint MOMBI (Figure 7) available for use if required. The minimum holding altitude at MOMBI was 5,600 ft AMSL. To use that minimum altitude, the crew was required to adhere to a maximum speed of 170 kt and a 14 DME limit from the Canberra DME for commencing the inbound turn back to MOMBI. A higher minimum holding altitude of 6,000 ft AMSL could also be used which allowed for a higher maximum speed of 210 kt with no DME limit.

Figure 7: Canberra runway 35 instrument landing system approach

Source: Airservices Australia, annotated by the ATSB

Increase to MOMBI holding pattern minimum altitude

Incorrect assessment area

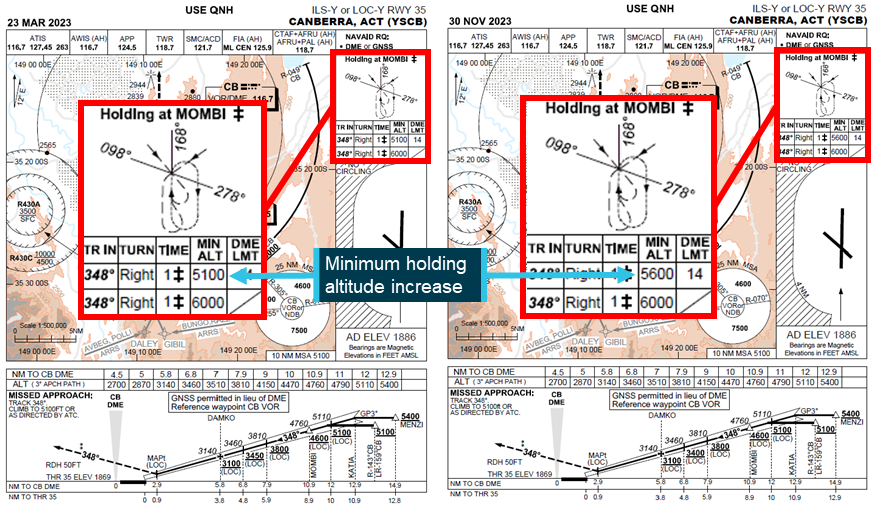

In March 2022, Airservices Australia undertook a required 3-yearly review of Canberra instrument flight procedures. During this review, the reference file for the MOMBI holding pattern could not be retrieved within the procedure design software. To conduct the review, the reviewing designer imported a new procedure template and assessed the relevant terrain and obstacles for the holding pattern. This assessment unintentionally omitted the area reduction associated with the 14 DME limit for the outbound leg of the holding pattern. Therefore, the assessed area was larger than necessary and included higher obstacles that necessitated an increase from the existing 170 kt speed‑limited minimum holding altitude of 5,100 ft to 5,600 ft. The minimum altitude for the 210 kt speed‑limited pattern remained 6,000 ft. These 170 kt and 210 kt speed‑limited minimum altitudes were respectively 840 ft and 1,240 ft above the unchanged 4,760 ft glidepath crossing height at MOMBI. The assessment and increased holding altitudes underwent an internal review, but the error was not identified. Airservices Australia then published the increase in the MOMBI holding pattern minimum altitude (Figure 8) via NOTAM.

Figure 8: Approach charts showing the increase to the MOMBI minimum holding altitude

The 23 March 2023 version of the approach chart was the last version to include the 5,100 ft minimum altitude, but from May 2022, the minimum altitude had been increased to 5,600 ft by NOTAM. Source: Airservices Australia, annotated by the ATSB

Glideslope intercept

Intercepting an ILS glideslope is normally accomplished from below as intercepting the glideslope from above requires high descent rates, increasing the risk of an unstable approach. Furthermore, the ILS ground equipment can also emit false glideslopes at steeper than normal glideslope angles. The Airservices Australia Aeronautical Information Publication cautioned that these false glideslopes could lead to a severe and sudden pitch up when intercepting a glideslope from above and that caution should be exercised in such situations, particularly for autopilot coupled approaches.[9]

The lowest of these false glideslopes typically occurs at an angle of about 9° to 12°, well above the flightpath of PK‑LDK during the incident approach.

Flight revalidation

In April 2022, the instrument flight procedure underwent a periodic revalidation flight by the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA). For this revalidation, Airservices Australia provided CASA with the results of the 3‑yearly review including the increased minimum holding altitudes. On 19 May 2022, following the revalidation flight, CASA provided the flight report to Airservices Australia. The report’s findings stated that:

- the suitability of the holding procedure design was unsatisfactory

- the holding altitude at MOMBI did not allow for an appropriate transition to the ILS glidepath

- the flyability of the ILS approach procedure was satisfactory

- modification of the procedure was desirable.

The report also recommended moving the holding point to the waypoint KATIA (if design requirements allowed).

Following receipt of the report, the findings were not incorporated into the associated instrument flight procedures and, on 30 November 2023, updated instrument flight procedures were published without modification, with the increased minimum holding altitude.

The Airservices Australia procedure design manual stated that upon receipt of an instrument flight procedure revalidation report, the chief designer would assign the report to the designer who compiled the relevant revalidation pack. Any issues identified by the report were required to be addressed and advice of any action taken needed to be provided to the chief designer. Airservices Australia advised that for the MOMBI holding pattern flight revalidation report, internal records of correspondence regarding the possible relocation of the holding pattern were located, but the record of the outcome could not be found.

CASA surveillance of instrument flight procedure design

CASA conducts regular surveillance of instrument flight procedures, including approach design. The surveillance included a review of the incorporation into flight procedures of relevant revalidation flight findings and recommendations. However, the surveillance was conducted on a sampling basis and therefore did not include every revalidation report finding. CASA surveillance activities did not include the MOMBI holding pattern findings and therefore it was not identified that these had not been incorporated into the published instrument approach procedure.

Action following Batik Air incident

In December 2024, following ATSB enquiries into the MOMBI holding pattern design, Airservices Australia conducted a review of the 2022 design changes. This review found that when the 14 DME limit was correctly incorporated into the terrain and obstacle assessment area, the higher terrain that caused the minimum altitude increase from 5,100 ft to 5,600 ft was excluded. This assessment also determined that the minimum altitude for the 210 kt speed limit could be reduced and, on 20 December 2024, Airservices Australia published a NOTAM reducing the MOMBI minimum holding altitudes to 5,100 ft for the 14 DME‑limited and 170 kt speed‑limited holding pattern and 5,600 ft (from 6,000 ft) for the 210 kt speed‑limited holding pattern.

Pilot details

The captain was an instructor pilot with Batik Air and held an Indonesian air transport pilot licence (aeroplane) and the required aviation medical certificates and operational ratings to undertake the flight. The captain had a total flying experience of 10,508 hours of which 7,772 were on the Boeing 737 aircraft type. In the previous 90 days, they had flown 164 hours, all in the Boeing 737.

The first officer held an Indonesian commercial pilot licence (aeroplane) and the required aviation medical certificates and operational ratings to undertake the flight. The first officer had a total flying experience of 6,843 hours of which 6,688 were on the Boeing 737 aircraft type. In the previous 90 days, they had flown 159 hours, all in the Boeing 737.

The second captain held an Indonesian air transport pilot licence (aeroplane) and the required aviation medical certificates and operational ratings to undertake the flight. The second captain had a total flying experience of 11,295 hours of which 11,018 were on the Boeing 737 aircraft type. In the previous 90 days, they had flown 191 hours, all in the Boeing 737.

From 1998 to 2010, the captain was a pilot in the Indonesian military and, in that role, had conducted operations in non‑controlled airspace. In 2010, the captain commenced employment with Batik Air’s parent company Lion Air and moved to Batik Air in 2013. From 2010, the captain had not undertaken any flights within non‑controlled airspace. The first officer and second captain reported having no experience operating in non‑controlled airspace. All crewmembers had previously operated flights to Australian destinations, but not to Canberra.

Batik Air

Batik Air began operations in 2013 as a subsidiary of Lion Air and commenced flights to Australia in 2016. At the time of the incident, Batik Air operated to 2 Australian destinations: Perth, Western Australia, and Canberra, Australian Capital Territory. The airline operated 46 Airbus A320 series aircraft, 22 Boeing 737‑800s and 1 Airbus A330‑300. All of Batik Air’s scheduled flights were undertaken in controlled airspace, except for any early Canberra arrivals (before 0600) and potential diversions from Perth Airport to the operator‑nominated diversion destination of Kalgoorlie, which operated using a CTAF at all times.

In October 2024, unrelated to this occurrence, Batik Air ceased operating the Denpasar to Canberra route.

Denpasar to Canberra route preparation

Prior to commencing the Denpasar to Canberra route, Batik Air conducted the required process to risk assess and obtain approval to commence the new route. This included conducting a risk management review and publishing a company airport briefing document.

Risk Management Review

The risk management review identified several risks and associated mitigations that were relevant to the incident including the items shown in Table 1 below:

Table 1: Relevant risk management review items

| Identified risk | Mitigation |

| Unfamiliarity with new route and new airport |

During the initial flight of any new route, provide the crew with all data available. If available, the initial flight is to be flown by a pilot who has previously had experience on the route. If such pilot is unavailable, an instructor captain shall operate the initial flight. |

| High obstacle standard instrument departure |

Create a specific one engine inoperative standard instrument departure procedure. Ensure the one engine inoperative standard instrument departure procedure is included in the company airport briefing document. |

| CTAF operations in non-controlled airspace/airports |

Ensure the crew is familiar with and understands CTAF operations. Ensure guidance of CTAF operations is included in the company airport briefing. |

| Airport area surrounded by obstacles. | Publish a company airport briefing and train crew for special airports. |

The risk management review did not identify that Canberra Airport aviation rescue and firefighting services operated only during times advised by NOTAM. Batik Air’s minimum permissible category of rescue and firefighting (RFF) services for 737‑800 operations was RFF category 7. On the day of the incident, this category of service began 13 minutes before the aircraft commenced the approach. Before that time, the available category of RFF was less than that permitted by Batik Air’s operations manual.

Company airport briefing

The company airport briefing document provided to the crew for the inaugural flight was incomplete. Specifically, in the airport information section the:

- radio frequency for company operations was listed as ‘TBA’ (to be advised)

- airport operating hours were listed as ‘24’, but the operational hours of air traffic control services were not provided

- aviation rescue and firefighting information provided did not state that services were only provided during hours advised by NOTAM, nor was it advised that outside of these hours, the available level of rescue and firefighting was less than that required for the 737‑800 by Batik Air.

The CTAF information and high obstacle standard instrument departure risk mitigations required by the risk management review were also not included in the briefing.

Common traffic advisory frequency procedures and training

Operations manual

Batik Air’s operations manual noted that Australian routes may require the use of non‑controlled aerodromes as alternate airports and that these airports did not provide 24‑hour air traffic control services. The manual did not provide information advising that Canberra, a destination airport, could also be non‑controlled at times. The manual provided adequate procedures for an arrival to a non‑controlled airport (destination or alternate), including the use of pilot‑activated lighting and guidance for appropriate CTAF procedures and radio broadcasts.

CTAF training

Prior to commencing operations into Australia, Batik Air flight crew were required to complete a module of online training for CTAF operations. All flight crew had completed this training prior to operating the incident flight.

Batik Air also incorporated CTAF use into one simulator session (session 15) of its recurrent training program. This session simulated a flight from Denpasar to Perth, Western Australia and included a diversion from Perth to Kalgoorlie, where pilots were trained in the use of CTAF procedures for the arrival into Kalgoorlie.

Session 15 had last been incorporated into Batik Air’s training program in 2020, 4 years prior to the incident flight. The captain last undertook this training in May of 2020 and the second captain in March of 2020. The first officer commenced employment with Batik Air in 2021 and had therefore not undertaken session 15.

Crew training before route commencement

Prior to commencing the Canberra route, Batik Air reviewed the route and associated operational requirements. Batik Air assessed that a proving flight on the route or simulator training were not required as the new destination did not involve any significant operational complexities, and the aircraft type had demonstrated the required performance capabilities when operating similar routes.

To prepare the crew for the new route, the chief pilot had provided an in-person briefing to the operating crew on the day of the flight.

CASA route approval process

In March 2023, Batik Air applied to CASA to extend its Australian services beyond Perth to 3 additional airports – Adelaide, Brisbane and Canberra.

CASA conducted a desktop review of the application that included examination of Batik Air’s organisational structure, operational certificates and manuals, infrastructure and operational approvals to ensure that the required items were in place. This included an assessment of Batik Air’s CTAF procedures and guidance. CASA did not review Batik Air’s risk management review or the company airport briefing for Canberra, nor was it required to.

International Civil Aviation Organization guidance

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) publication Annex 6 to the convention on international civil aviation, Operation of Aircraft provided guidance for appropriate flight crew qualification and training standards for international air transport operations.[10] This stated that an operator shall not utilise a pilot as pilot‑in‑command of an aeroplane on a route for which that pilot was not qualified until the pilot has demonstrated adequate knowledge of relevant operational details for the route including:

- terrain and minimum safe altitudes

- communication and air traffic facilities, services and procedures

- rescue procedures

- arrival, departure, holding and instrument approach procedures

- applicable operating minima.

This demonstration relating to arrival, departure, holding and instrument approach procedures could be accomplished in an appropriate training device, such as a simulator.

The guidance also stated that a pilot shall have made an actual approach into each aerodrome of landing on the route accompanied by a pilot who is qualified for the aerodrome unless:

- the approach to the aerodrome is not over difficult terrain and the instrument approach procedures and aids available are similar to those with which the pilot is familiar, and a margin to be approved by the State of the Operator is added to the normal operating minima, or there is reasonable certainty that approach and landing can be made in visual meteorological conditions; or

- the descent from the initial approach altitude can be made by day in visual meteorological conditions; or

- the operator qualifies the pilot-in-command to land at the aerodrome concerned by means of an adequate pictorial presentation; or

- the aerodrome concerned is adjacent to another aerodrome at which the pilot-in-command is currently qualified to land.

It was also recommended that a pilot be requalified if more than 12 months had elapsed and the pilot ‘had not made a trip on the route or a route in close proximity and over similar terrain and had not practised such procedures in a training device’.

The ICAO publication Guidance on the Preparation of an Operations Manual provided further guidance for these operations.[11] This document noted that it was common practice for operators to apply similar requirements to all pilots (not just the pilot in command). Depending on the complexity of the area or route and aerodrome, this may require in‑flight familiarisation or familiarisation using a training device. This document also stated that it was normal practice to give each pilot a general route or line check at least every 12 months.

Collision avoidance at non‑controlled aerodromes

Non‑controlled aerodromes cater for flights conducted by a broad mix of aircraft under both the instrument flight rules and the visual flight rules, including:

- larger turboprop, jet and powered lift aircraft

- smaller aircraft operated both commercially and privately

- agricultural aircraft

- military aircraft

- various sport and recreational aircraft.

This presents many challenges to pilots operating into, out of, or in the vicinity of these aerodromes including collision avoidance. The Civil Aviation Safety Authority advisory circular AC91-14 pilots’ responsibility for collision avoidance describes the 2 methods of collision avoidance for aircraft operating in the vicinity of non‑controlled aerodromes.

Unalerted see‑and‑avoid:

Unalerted see-and-avoid relies totally on the crew – with no other assistance – to visually detect other aircraft that are on a conflicting flight path. Unalerted see-and-avoid is only viable in a minority of circumstances when all the following factors are present to defend against a mid-air [collision]:

- horizontal closure rates are slow enough for human reaction

- vertical closure rates are slow enough for human reaction

- aircraft are of sufficient profile to be seen with the available ambient light, or are made sufficiently conspicuous using artificial lighting

- aircraft and/or the ground are sufficiently well lit or ambient light provides sufficient contrast

- the aircraft structure is such that the pilot’s visibility is unhindered in all directions (a near practical impossibility)

Alerted see‑and‑avoid:

As aviation developed, with increasing aircraft performance, traffic density and flight in non-visual conditions, it became apparent that unalerted see-and-avoid had significant limitations. The need to enhance a pilot’s situational awareness led to the principle of ‘alerted see-and-avoid’. The primary tool of alerted see-and-avoid is radio communication. Radio allows for the communication of information to the pilot from the ground or from other aircraft.

Other tools of alerted see‑and‑avoid include airborne collision avoidance systems, but the equipment required for these systems to provide effective alerting were not required for all aircraft types using non‑controlled aerodromes.

The advisory circular describes accurate provision and interpretation of traffic information for the purposes of separation to or from another aircraft as an essential pilot skill and stated that effective training in the use of radio procedures is vital to ensure crews can effectively operate at non‑controlled aerodromes using common traffic advisory frequencies. Without understanding and confirming the transmitted information, the potential for alerted see‑and‑avoid is reduced to the less safe situation of unalerted see‑and‑avoid.

Light and meteorology

The approach was conducted in clear night conditions. On the morning of 14 June 2024, first light[12] was at 0641, 39 minutes after the aircraft landed. The moon was below the horizon. At 0554, when the aircraft descended below the minimum holding altitude, the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) automatic weather station at Canberra Airport recorded the wind as 1 kt from 141° magnetic. The station recorded that there was no cloud cover, and visibility was greater than 10 km.

Recorded data

Quick access recorder

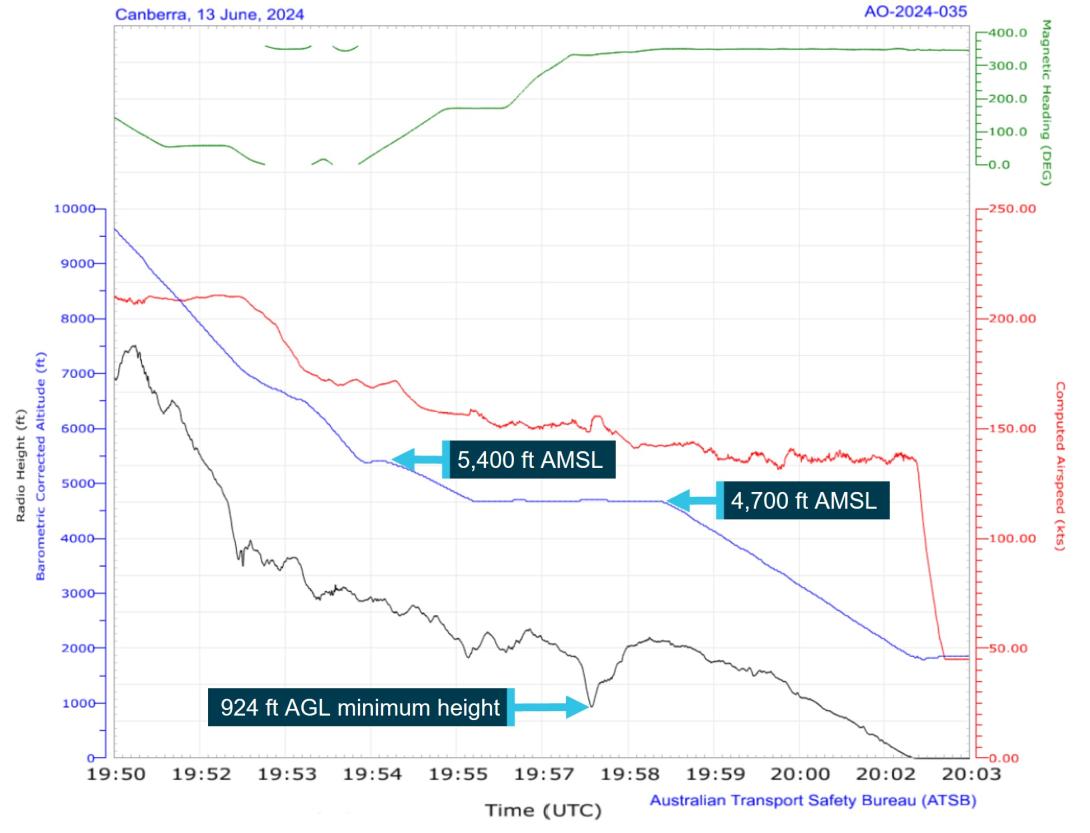

The aircraft’s quick access recorder data was provided to the ATSB by Batik Air. This data captured the aircraft’s descent commencing from 10,000 ft AMSL at 0550:20, 2.3 NM after passing LANYO. It then continued descending past the waypoints of HONEY at 9,184 ft AMSL, DALEY at 7,104 ft and MENZI at 6,720 ft (680 ft above the ILS glideslope).

At 0554:15, while approaching MOMBI at a speed of 171 kt, the aircraft descended below 5,600 ft AMSL and 2 seconds later, 0.6 NM before crossing MOMBI, the aircraft commenced a right turn from the approach track into the holding pattern at a speed of 172 kt. At 0554:24, the aircraft levelled at 5,400 ft AMSL and 6 seconds later passed MOMBI at a speed of 169 kt while continuing the right turn.

At 0554:51, the aircraft commenced descending from 5,400 ft AMSL and 4 seconds later, airspeed increased to 172 kt, before reducing to 170 kt, 4 seconds later. Speed remained at or below 170 kt for the remainder of the flight.

At 0555:44, the aircraft turned to and maintained a heading of 170° and 15 seconds later levelled at 4,700 ft AMSL (Figure 9). At 0556:25, the aircraft proceeded beyond 14 DME from the Canberra DME before commencing the right turn toward MOMBI 4 seconds later. During this turn, the lowest recorded radio height was 924 ft above ground level (AGL). No ground proximity alerts were recorded.

The aircraft passed KATIA at 0557:53 at an altitude of 4,700 ft AMSL (700 ft below the ILS approach minimum altitude at that waypoint) while tracking back toward MOMBI and rejoined the approach about 12 NM from the Canberra DME at 0558:19.

At 0558:48, the aircraft began descending from 4,700 ft along the runway 35 glidepath (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Recorded quick access data

All times are coordinated universal time (UTC). Local time was Australian Eastern Standard Time (EST), which was (UTC) +10 hours. Source: Quick access recorder from PK-LDK, annotated by the ATSB

Air traffic control

Recorded air traffic control surveillance and communications audio data was provided by Airservices Australia. The recorded audio showed that:

- the crew did not request, and were not provided with, a clearance to track via the AVBEG 5A STAR

- no safety alert was provided by the Melbourne Centre controller

- no broadcasts were made by the crew on the Canberra CTAF

- at 0547, and again at 0555, the Canberra runway lighting system was activated using the pilot‑activated lighting. The Batik Air crew did not have the CTAF selected at that time and the only other recorded transmissions on the CTAF at around those times were from a ground vehicle and another aircraft preparing to taxi for departure

- at 0558, the Canberra Approach controller established communication with the Batik Air crew and provided a safety alert.

Safety analysis

Deviation from clearance and controller response

While en route to Canberra, the flight crew were provided with a tracking clearance from the waypoint AVBEG direct to Canberra Airport and instructed to leave controlled airspace by descending below the 8,500 ft above mean sea level (AMSL) controlled airspace base along that track.

The crew’s normal practice for arrivals was to use a standard arrival route (STAR), and they prepared for the arrival at Canberra using the AVBEG 5A STAR. However, the crew did not request or receive a clearance to descend via the STAR and with Canberra Approach air traffic control (ATC) services not yet active, this clearance could not have been provided. Therefore, when the aircraft crossed AVBEG and commenced tracking via the STAR, it deviated from the provided clearance.

From AVBEG, this STAR deviated from the aircraft’s cleared track by turning south and crossed restricted areas R430A, B and C. The AVBEG 5A STAR included a 10,000 ft AMSL descent limitation until past the waypoint LANYO to ensure that crew using the STAR did not enter the uppermost of these restricted areas. The descent clearance for the direct track provided to the crew did not have a descent restriction and the controller was unaware that the AVBEG 5A STAR included a descent restriction to prevent the aircraft entering the restricted areas. Therefore, the controller was required to issue a safety alert as it appeared to them that the aircraft’s deviation would take the aircraft into the active restricted areas. However, at that time, the controller had only recently taken over management of the airspace and was unsure if the crew were deviating from the cleared route, or if a clearance had been provided which hadn’t been correctly entered in the air traffic control system and was therefore not visible to the controller. Additionally, the controller noted that the aircraft was still 17 NM from the restricted area and therefore, instead of advising the crew of the clearance deviation and issuing a safety alert, the controller intervened by issuing a descent altitude restriction.

The crew believed that they were correctly following the AVBEG 5A STAR into non‑controlled airspace and when they received the descent restriction from the controller, they became confused as to whether the approach would be conducted within, or outside of, controlled airspace. Despite the controller stating that the approach would take place outside of controlled airspace and that clearances were not required for the manoeuvring associated with the approach, the crew remained confused and made several clearance requests when operating in non‑controlled airspace. This confusion was only resolved when Canberra Approach and Tower services commenced, and the approach continued using those services.

A ‘safety alert’ is designed to alert crews to safety critical information to ensure a response is prioritised. The controller’s decision not to issue the safety alert and not to alert the crew to the deviation were missed opportunities to draw the crew’s attention to the situation and may have helped avoid the later confusion about the airspace classification.

Furthermore, the controller needed to wait until the aircraft was observed to be 2.5 NM beyond the restricted area before further descent clearances could be provided and by the time this clearance was issued, the aircraft was about 1,300 ft above the desired STAR profile.

|

Contributing factor While descending and tracking direct toward Canberra in controlled airspace, the flight crew were provided with a clearance to leave the controlled airspace by continuing to descend on that track. The flight crew then deviated from the cleared track by commencing the AVBEG 5A standard arrival route (STAR). |

|

Contributing factor The air traffic controller did not advise the flight crew of the track deviation or provide a safety alert but provided altitude instructions to maintain separation from a restricted area (a separation built into the AVBEG 5A STAR). This intervention resulted in the aircraft becoming higher than the desired descent profile and the crew becoming confused regarding the airspace classification for the arrival and approach. |

Descent below minimum altitude

Incorrectly flown holding pattern

Following the controller’s descent clearance after crossing the restricted area, the crew did not re‑establish the desired descent profile prior to commencing the approach. Consequently, the aircraft passed the instrument landing system approach’s initial approach fix waypoint MENZI about 680 ft higher than the glideslope and the captain decided to use the approach holding pattern at MOMBI to descend to the desired descent profile. This decision was made late during the arrival and the crew did not identify that the holding pattern minimum altitude (5,600 ft) was unusual in being significantly higher than the waypoint glideslope crossing altitude (4,760 ft). As a result, the captain referenced the 4,760 ft AMSL glideslope crossing altitude for MOMBI and selected 4,700 ft for the holding altitude.

The crew also did not begin to enter the pattern into the flight management system until after MOMBI had already dropped from the programmed track. As a result, the first officer had to manually enter the holding waypoint. When entering the holding waypoint, the first officer did not enter minimum altitude constraints associated with the holding pattern.

While the first officer entered the holding waypoint, the captain used the heading select function and altitude window to enter the holding pattern. In doing so, the captain did not adhere to several holding pattern requirements. The turn to enter the pattern commenced prior to the aircraft crossing MOMBI resulting in less distance being available to complete the outbound leg of the holding pattern. The maximum speed for the 5,600 ft minimum altitude was marginally exceeded and the aircraft then descended below the 5,600 ft minimum altitude to the commanded altitude of 4,700 ft. As the pattern continued, the inbound turn to MOMBI then did not commence until after the aircraft had proceeded beyond the 14 DME limit. As the aircraft was operating below both the 6,000 ft minimum altitude of the non‑distance restricted holding pattern and the 7,500 ft 25 NM minimum safe altitude, obstacle and terrain clearance was not assured.

As the aircraft turned toward back toward MOMBI at an altitude 900 ft below the minimum safe altitude, it crossed over terrain at a height of 924 ft above ground level. The aircraft did not penetrate the enhanced ground proximity warning system envelope and no alert was generated. Furthermore, as the aircraft then turned to rejoin the approach, it was now positioned about 700 ft below the minimum altitude for that segment of the approach, which also reduced obstacle clearance assurance during this part of the flight.

|

Contributing factor The aircraft passed the initial approach fix for the instrument landing system approach about 680 ft higher than the glideslope and the crew intended to use the holding pattern at the approach waypoint of MOMBI to reduce altitude. However, the holding pattern was not correctly flown, and the aircraft was manoeuvred significantly below the minimum safe altitude. The approach was then recommenced from an altitude about 700 ft below the minimum altitude. |

Low altitude safety alerts

Unlike approach controllers, area radar controllers providing the flight information service for the non‑controlled airspace were not required to know the details of instrument flight procedures for airports in that airspace. Therefore, the controller providing the flight information service was not aware of the minimum holding altitudes associated with the MOMBI holding pattern.

Air traffic control procedures required the controller to issue a safety alert as soon as they became aware that the aircraft was in unsafe proximity to terrain. However, the controller was unaware of the minimum holding altitudes and descending below the broader lowest safe altitudes was inherent to the progress of a flight following an instrument approach. Therefore, the controller did not become aware that the aircraft was operating below the minimum safe altitudes and did not issue a safety alert. Had an alert been provided when the aircraft first descended below the minimum altitude, this would have occurred prior to the aircraft turning toward the high terrain, reducing the risk of collision with terrain.

The Canberra Tower and Approach controllers both recognised that the aircraft was operating below the minimum safe altitude. The Tower controller attempted to contact the crew however, as the crew had not selected the CTAF, these broadcasts were not received. After the aircraft rejoined the approach, the Approach controller took over the airspace and immediately provided a safety alert to the crew, but by this time the aircraft was re‑established on the approach and within the associated protected area.

|

Other factor that increased risk The Melbourne Centre air traffic controller providing the flight information service for the aircraft was not, and was not required to be, aware of the holding pattern minimum altitudes. Therefore, the controller did not issue a safety alert when the aircraft descended below the minimum safe altitude. |

Common traffic advisory frequency use and training

Non-use of Canberra common traffic advisory frequency

During the arrival and approach, the crew were confused about the airspace classification and despite attempts by the controller to clarify this, the confusion was not resolved. As the aircraft approached Canberra Airport the crew did not select the Canberra common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF) but remained on the Melbourne Centre frequency.

As a result, the crew could not have activated the runway lights, nor could they make the required radio broadcasts to ensure separation with other traffic using the airspace. However, at the time the aircraft approached Canberra, another CTAF user had illuminated the runway lights and there was no conflicting traffic using the CTAF.

More importantly however, as the crew had not selected the CTAF, they did not receive the oncoming Canberra Tower controller’s broadcasts attempting to alert them to their low altitude.

|

Contributing factor The Canberra common traffic advisory frequency was not selected by the crew, and the appropriate radio broadcasts were not made. This prevented the crew from receiving the oncoming Canberra tower air traffic controller's safety alerts, being able to illuminate the runway lights and increased the risk of conflict with other traffic. |

Batik Air common traffic advisory frequency training

Batik Air’s operations manual included guidance on CTAF operations. While this guidance was focused on a Kalgoorlie diversion scenario, this guidance was also suitable for an early morning Canberra arrival.

Australian flights are the only flights in Batik Air’s route network where CTAF operations may have been required and Batik Air required that crew complete online CTAF training before operating to Australia. A simulator training session had also been developed that included CTAF operations, but this had last been incorporated into Batik Air’s recurrent training program 4 years prior to the incident, in 2020. The captain and deadheading captain had completed this session over 4 years before the incident, but the first officer had joined Batik Air after this date and had not undergone the training. None of the crew had previously operated into a non‑controlled airport as an operating crew of an air transport flight.

International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) guidance recommended that a pilot acting as pilot‑in‑command undergo training and demonstrate the required knowledge relevant to an intended operation within 12 months of undertaking that operation. Furthermore, this guidance stated that it was commonplace to ensure that all flight crew (not just the pilot‑in‑command) were trained and demonstrated similar operation knowledge.

Operating to a non‑controlled airport in an air transport aircraft while using CTAF procedures is a complex task. The crews of these aircraft may be faced with managing separation with smaller commercial and private aircraft as well as agricultural, military or sport and recreational aircraft. In addition, these aircraft may be operating to either the visual or instrument flight rules and many of these aircraft are not required to be fitted with the equipment required to enable effective alerting using airborne collision avoidance systems. Furthermore, these crews may be required to manage additional tasks like activating the runway lighting when arriving at night.

Effective training in the use of CTAF procedures is vital to ensure crews can effectively and safely operate using these procedures, in particular for crews who may not have previously used them or seldom used them. Batik Air had identified this risk for its Australian operations and developed training to mitigate the risk. However, this training was not conducted regularly, and Batik Air processes did not ensure that all flight crew members had completed the training before undertaking operations to Australia. This was inconsistent with the standards set out by ICAO guidance and increased the risk that crews would be inadequately prepared to manage this task.

After the crew deviated from the airways clearance, the controller’s intervention resulted in the crew becoming confused as to the classification of the airspace for the arrival and approach. This may have contributed to the crew’s non‑use of the CTAF. However, as the non‑use of CTAF procedures did not lead to the descent below minimum altitude, the inadequate CTAF training was not considered contributory to the incident.

|

Other factor that increased risk Batik Air did not ensure that flight crew completed all common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF) training prior to them operating flights into Australia where the use of these procedures could be required. (Safety issue) |

Route commencement process

Prior to commencing the Denpasar to Canberra route, Batik Air completed the required process to receive approval to commence flights on the route. This included a risk management review for the intended operation which identified a number of risks and associated mitigation actions that were relevant to the operation. However, a number of mitigations were not implemented such as the absence of CTAF guidance and a one engine inoperative standard instrument departure in the company airport briefing document. Other mitigations that were implemented, such as the inclusion of an instructor pilot on the flight and the publication of an (incomplete) company airport briefing document were ineffective at mitigating the risk of operating to an unfamiliar airport. Furthermore, the risk presented by airport fire and firefighting services being unavailable at times was not identified and therefore, no mitigating action was implemented.

ICAO guidance stated that an operator should not utilise a pilot as pilot‑in‑command of an aeroplane on a route for which that pilot was not qualified until the pilot had demonstrated adequate knowledge of relevant operational details. This could be conducted in a number of ways including self‑briefing, operator briefing, undertaking a route proving flight or by using an adequate training device.

Batik Air assessed that a proving flight or simulator training for the route were not required as the new destination did not involve any significant operational complexities and the aircraft type had demonstrated the required performance capabilities when operating similar routes. Instead, the crew were briefed on the operation by the Chief Pilot on the day of the flight.

However, the route did involve several significant operation complexities. The scheduled arrival time for the flight was during night hours; Canberra is surrounded by mountainous terrain and may have required the use of CTAF procedures. Furthermore, the runway 35 instrument landing system approach included significant and unusual complexities as demonstrated by the MOMBI holding pattern glideslope transition.

Recognising that a briefing was provided by the Chief Pilot to the crew prior to the flight, it did not achieve its aim of adequately preparing them for the route. A route proving flight, or the use of a suitable training device, would likely have provided more effective crew preparation in accordance with ICAO guidance, giving them greater awareness of the terrain, airspace and instrument flight procedure complexities of Canberra and may have avoided the descent below the minimum safe altitude.

|

Contributing factor Batik Air's change management processes were not effective at fully identifying and mitigating the risks associated with the commencement of the Denpasar to Canberra route. (Safety issue) |

Holding pattern to glideslope transition design

During a required, periodic review of the Canberra runway 35 ILS approach procedure by Airservices Australia, a new procedure template was imported to assess the approach including the MOMBI holding pattern as the existing design could not be uploaded to the procedure design software. The lower of the existing holding pattern’s 2 minimum altitudes (5,100 ft AMSL) required a crew to turn inbound from the outbound course before reaching 14 DME from Canberra. This distance limitation reduced the size of the pattern’s terrain and obstacle consideration area. When conducting the review, this 14 DME distance limitation was not included when determining the assessment area and therefore an area larger than required was assessed. This larger area included higher terrain and obstacles that required a 500 ft increase to the minimum altitude, raising it to 5,600 ft AMSL. The error in this assessment was not identified during internal reviews by Airservices Australia and the increased holding altitude was then published via NOTAM.

The approach glideslope crossed MOMBI at 4,760 ft AMSL, 840 ft below the minimum holding altitude. Consequently, to rejoin the approach from the holding pattern, crews could be required to intercept the glideslope from significantly above it, increasing the risk of sudden pitch ups. To achieve this could also require significant descent rates, increasing the risk of unstable approaches.

This was identified when the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) conducted a revalidation flight of the holding pattern and determined that the transition from the pattern to the glideslope was not appropriate and the design was unsatisfactory. This feedback was provided to Airservices Australia and despite Airservices Australia’s internal processes requiring this feedback to be addressed, the approach procedure with the increased altitude was published without any further modification.

The erroneous minimum altitude remained in place for over 2 years until a review following the Batik Air incident. This review identified the assessment area error and resulted in the minimum altitude being lowered back to 5,100 ft AMSL. While this minimum altitude remains above the MOMBI glideslope crossing altitude, the 500 ft reduction allows crews to appropriately transition to the glideslope while on the inbound leg of the holding pattern.

While the transition increased the risk of unstable and sudden pitch ups approaches, it did not contribute to the incident as the captain had manually selected a holding altitude of 4,700 ft AMSL on the flight management system, which in turn descended the aircraft below the lower and more appropriate 5,100 ft AMSL minimum altitude.

|

Other factor that increased risk During a 2022 review of Canberra runway 35 instrument landing system approaches, an obstacle evaluation error led to Airservices Australia increasing the MOMBI holding pattern minimum altitude from 5,100 ft to 5,600 ft. This increase resulted in a transition from the holding pattern to the approach glideslope that increased risk of unstable approaches and sudden pitch ups. |

|

Other factor that increased risk After conducting a revalidation test flight of the holding pattern minimum altitude increase, the Civil Aviation Safety Authority advised Airservices Australia that the increased minimum altitude did not provide an appropriate transition to the approach glideslope and recommended moving the holding location to the waypoint KATIA. Despite Airservices Australia receiving this advice, the holding waypoint remained at MOMBI and the increased minimum holding altitude was maintained. |

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. Safety issues are highlighted in bold to emphasise their importance. A safety issue is a safety factor that (a) can reasonably be regarded as having the potential to adversely affect the safety of future operations, and (b) is a characteristic of an organisation or a system, rather than a characteristic of a specific individual, or characteristic of an operating environment at a specific point in time. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the flight below minimum altitude involving Boeing 737‑800, PK-LDK, 19 km south of Canberra Airport, New South Wales on 14 June 2024.

Contributing factors

- While descending and tracking direct toward Canberra in controlled airspace, the flight crew were provided with a clearance to leave the controlled airspace by continuing to descend on that track. The flight crew then deviated from the cleared track by commencing the AVBEG 5A standard arrival route (STAR).

- The air traffic controller did not advise the flight crew of the track deviation or provide a safety alert but provided altitude instructions to maintain separation from a restricted area (a separation built into the AVBEG 5A STAR). This intervention resulted in the aircraft becoming higher than the desired descent profile and the crew becoming confused regarding the airspace classification for the arrival and approach.

- The aircraft passed the initial approach fix for the instrument landing system approach about 680 ft higher than the glideslope and the flight crew intended to use the holding pattern at the approach waypoint of MOMBI to reduce altitude. However, the holding pattern was not correctly flown, and the aircraft was manoeuvred significantly below the minimum safe altitude. The approach was then recommenced from an altitude about 700 ft below the minimum altitude.

- The Canberra common traffic advisory frequency was not selected by the flight crew, and the appropriate radio broadcasts were not made. This prevented the crew from receiving the oncoming Canberra tower air traffic controller's safety alerts, being able to illuminate the runway lights and increased the risk of conflict with other traffic.

- Batik Air's change management processes were not effective at fully identifying and mitigating the risks associated with the commencement of the Denpasar to Canberra route. (Safety issue)

Other factors that increased risk

- Batik Air did not ensure that flight crew completed all common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF) training prior to them operating flights into Australia where the use of these procedures could be required. (Safety issue)

- During a 2022 review of Canberra runway 35 instrument landing system approaches, an obstacle evaluation error led to Airservices Australia increasing the MOMBI holding pattern minimum altitude from 5,100 ft to 5,600 ft. This increase resulted in a transition from the holding pattern to the approach glideslope that increased risk of unstable approaches and sudden pitch ups.

- After conducting a revalidation test flight of the holding pattern minimum altitude increase, the Civil Aviation Safety Authority advised Airservices Australia that the increased minimum altitude did not provide an appropriate transition to the approach glideslope and recommended modifications to the holding pattern design. Despite Airservices Australia receiving this advice, no changes were made and the increased minimum holding altitude was maintained.

- The Melbourne Centre air traffic controller providing the flight information service for the aircraft was not, and was not required to be, aware of the holding pattern minimum altitudes. Therefore, the controller did not issue a safety alert when the aircraft descended below the minimum safe altitude.

Safety issues and actions

Batik Air common traffic advisory frequency training

Safety issue number: AO-2024-035-SI-01

Safety issue description: Batik Air did not ensure that flight crew completed all common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF) training prior to them operating flights into Australia where the use of these procedures could be required.

Batik Air change management process

Safety issue number: AO-2024-035-SI-02

Safety issue description: Batik Air's change management processes were not effective at fully identifying and mitigating the risks associated with the commencement of the Denpasar to Canberra route.

Proactive safety action not associated with a safety issue

| Action number: | AO-2024-035-PSA-03 |

| Action organisation: | Batik Air |

| Action status: | Closed |

Batik Air adjusted the flight schedule for the Denpasar to Canberra flight (6015) to ensure that all Canberra arrivals occur during Canberra Tower and Approach air traffic control operating hours.

Glossary

| AGL | Above ground level |

| AMSL | Above mean sea level |

| ATC | Air traffic control |

| CASA | Civil Aviation Safety Authority |

| CTAF | Common traffic advisory frequency |

| DME | Distance measuring equipment |

| FL | Flight level |

| FMS | Flight management system |

| ICAO | International Civil Aviation Organization |

| ILS | Instrument landing system |

| MCP | Mode control panel |

| NOTAM | Notice to airmen |

| PF | Pilot flying |

| PM | Pilot monitoring |

| STAR | Standard arrival route |

| TIBA | Traffic information by aircraft |

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- Batik Air

- the flight crew

- the air traffic controller

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Airservices Australia

- recorded flight data from PK-LDK

- Bureau of Meteorology.

References

International Civil Aviation Organization 2018, Annex 6 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, Operation of Aircraft, Part 1 International Commercial Air Transport — Aeroplanes Eleventh Edition.

International Civil Aviation Organization 2023, Doc 10153, Guidance on the Preparation of an Operations Manual.

Civil Aviation Safety Authority 2025, Advisory Circular AC91-14 Pilots’ responsibility for collision avoidance.

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- Batik Air

- the flight crew

- the air traffic controller

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Airservices Australia

- National Transportation Safety Committee of Indonesia.

Submissions were received from:

- Batik Air

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Airservices Australia

- National Transportation Safety Committee of Indonesia.

The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2025

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this report is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. The CC BY 4.0 licence enables you to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon our material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] Pilot flying (PF) and Pilot monitoring (PM): procedurally assigned roles with specifically assigned duties at specific stages of a flight. The PF does most of the flying, except in defined circumstances such as planning for descent, approach and landing. The PM carries out support duties and monitors the PF’s actions and the aircraft’s flight path.

[2] Jump seat: an auxiliary seat on the aircraft flight deck.

[3] Flight level: at altitudes above 10,000 ft in Australia, an aircraft’s height above mean sea level is referred to as a flight level (FL). FL 350 equates to 35,000 ft.

[4] All headings used in the report are magnetic.

[5] NOTAM: a notice distributed by means of telecommunication containing information concerning the establishment, condition or change in any aeronautical facility, service, procedure or hazard, the timely knowledge of which is essential to personnel concerned with flight operations.

[6] Airservices Australia’s levels of aviation rescue firefighting services available at Australia’s 26 busiest airports range from category 6 to category 10 services with the categories dictating number of response personnel, response times, water discharge rates and the required amount of water and foam that is needed to be carried. The category of service provided was determined by the size (length and width) of the largest aircraft serving an airport.

[7] Manual of air traffic standards, 4.2.21.1 Entering an active Restricted/Military Operating Area and 9.1.4.3 Issuing a safety alert.

[8] Manual of air traffic standards, 9.7.12.4 Flight path deviation.