Executive summary

What happened

On 7 December 2023, at 1930 local time, a Robinson R22 Beta 2 helicopter, registered VH-DLD, departed from Bloodwood Station, Northern Territory, on a private flight to Gorrie Station, Northern Territory. The helicopter was last seen by witnesses on the ground at about 1945 and a search for the helicopter was initiated at about 2015. The wreckage was found on the afternoon of 9 December. The helicopter was destroyed and the pilot, who was the sole occupant, was fatally injured.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that the pilot departed after last light for a return home flight on a dark night but was not qualified to fly at night and the helicopter was not equipped to be flown at night. While it was reported that the pilot had some night flying experience, the helicopter was not fitted with an artificial horizon. Without the minimum instruments and training, it was unlikely that the pilot would have been able to orientate the helicopter without external visual references.

It is likely that during the return home flight, the helicopter entered a smoke plume associated with bushfires under dark night conditions and the pilot became spatially disorientated after losing external visual references. This resulted in the helicopter colliding with terrain uncontrolled at high speed.

Safety message

Night conditions can result in little to no useable external visual cues and in these environments day visual flight rules (VFR) pilots are at risk of spatial disorientation and loss of control of their aircraft. The ATSB’s Avoidable Accidents No 7 - Visual flight at night accidents provides further discussion of these risks and how they have contributed to accidents. The requirement to only operate under daylight conditions, and plan to land 10 minutes before last light, provides a reliable method for ensuring there are sufficient external visual references available to safely operate.

In 2022, the Civil Aviation Safety Authority published their advisory circular for the night visual flight rules rating, AC 61-05 v1.1 - Night VFR rating (casa.gov.au), which provides guidance on the requirements for the granting of night VFR ratings, as well as the conduct of operations under night VFR. The advisory circular highlighted the hazards of night flying and provided advice to pilots and others on how to safely conduct night operations. The ATSB encourages everyone involved in night flying or considering night operations to familiarise themselves with the contents of the advisory circular.

The investigation

| Decisions regarding the scope of an investigation are based on many factors, including the level of safety benefit likely to be obtained from an investigation and the associated resources required. For this occurrence, a limited-scope investigation was conducted in order to produce a short investigation report and allow for greater industry awareness of findings that affect safety and potential learning opportunities. |

The occurrence

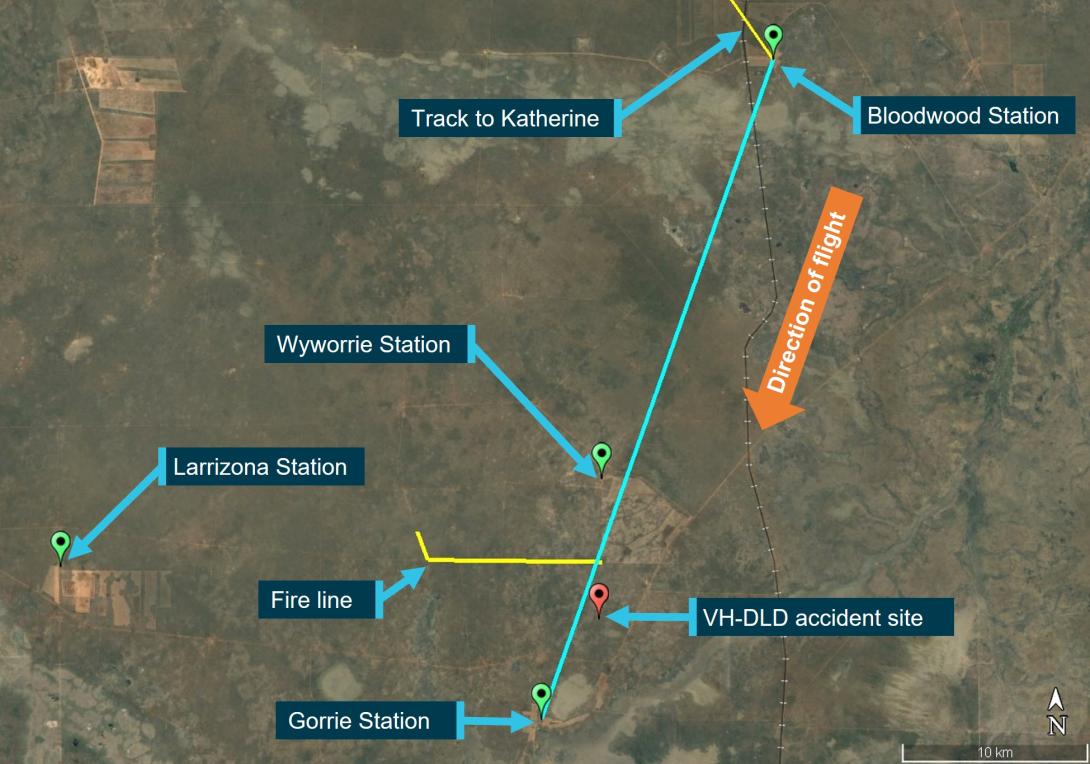

On 7 December 2023, at about 1930[1] local time, a Robinson R22 Beta 2 helicopter, registered VH-DLD, departed from Bloodwood Station, Northern Territory (NT) on a private flight to the pilot’s home at Gorrie Station, NT (Figure 1). The pilot was the sole occupant. Bloodwood was located about 48 NM south-east of Katherine, where last light[2] was at 1924 on 7 December. The flight from Bloodwood to Gorrie was about 21 NM on a direct track of 200° (True).

Figure 1: Direct track from Bloodwood Station to Gorrie Station

The track line from Bloodwood Station to Gorrie Station is representative of a direct track and not the actual flightpath. The position of the fire line was based on a hand drawing by the pilot’s relative based at Wyworrie Station.

Source: Google Earth, annotated by ATSB

Earlier in the evening, just after 1900, the caretaker at Gorrie switched the helicopter hangar lights on to illuminate the helicopter landing pad.[3] The caretaker then received a radio call from the pilot at about 1915 to request the activation of the lights, to which the caretaker replied that the lights were already on. This was about the time the helicopter arrived at Bloodwood where the pilot had stopped for a brief social visit. Just prior to 1930, the owner of Bloodwood advised the pilot that it was getting dark outside and offered the pilot a bed for the night. However, the pilot declined the offer and departed. The owner of Bloodwood reported that it was about a 17-minute flight from Bloodwood to Gorrie in the R22 in calm conditions.

At about 1945, two of the pilot’s relatives, who were sitting outside for dinner at Wyworrie Station (located about 13.5 NM along the track from Bloodwood to Gorrie), observed the silhouette of the helicopter, with the navigation and strobe lights on, pass in front of their homestead, tracking towards Gorrie. They both noted the helicopter was tracking towards smoke from fires located on the southern boundary of Wyworrie. It was at about this time that the pilot made another radio call to the caretaker at Gorrie to confirm the lights were on. The caretaker checked outside and then confirmed that they were on. At this stage, the caretaker started to become concerned because the pilot sounded a ‘little bit disorientated’ and the caretaker could not recall the pilot ever previously challenging the status of the lights.

Residents at Larrizona Station, located 14.7 NM west-north-west of Gorrie, monitored the same radio frequency as Gorrie and Wyworrie. The manager at Larrizona heard the radio calls between the pilot and the Gorrie caretaker about the lights. They reported that the second radio call at 1945 was unusual because the clarity of the call on the Larrizona radio indicated the helicopter was likely close to Gorrie and that the pilot should have been able to see the lights.

At about 2015, the Gorrie caretaker called the pilot’s relatives at Wyworrie to ask if the helicopter had landed there. On being advised that the helicopter had not landed at Gorrie, the pilot’s family initiated the search and rescue process. At about 1730 on 9 December, the helicopter wreckage was found about 4 NM (7.5 km) south of the Wyworrie homestead and 3.3 NM (6.1 km) north‑north‑east of the Gorrie homestead.[4] The pilot was fatally injured.

Context

Pilot information

The pilot was initially issued with a commercial pilot licence (helicopter) on 7 April 2011,[5] and held a class endorsement for single-engine helicopters with a low-level and an aerial mustering rating for helicopters. The pilot completed a Class 1 medical examination on 24 January 2023 and a flight review on 13 February 2023 in a Robinson R44 helicopter. The pilot recorded 6,700 flight hours experience on the medical examination submission and the medical certificate was issued with 2 restrictions – for distance vision correction and for a headset to be worn.

The remains of a headset were found at the accident site and one of the pilot’s relatives reported the pilot always flew with prescription sunglasses and had prescription glasses for driving at night. However, it was unknown if the pilot was wearing the night driving glasses during the flight. The pilot did not hold a night visual flight rules (VFR)[6] rating but had reportedly completed some night flying training and had arrived home after last light on previous occasions.

Helicopter information

The helicopter, registered VH-DLD, was a 2-seat Robinson Helicopter Company R22 Beta 2 helicopter, serial number 3675, powered by a Textron Lycoming O-360-J2A 4-cylinder piston engine (Figure 2). The helicopter was manufactured in the United States in 2004, first registered in Australia on 31 August 2004, and issued with a Certificate of Airworthiness on 7 October 2004.

Figure 2: VH-DLD

Source: Pilot’s relative

The most recent maintenance release was issued on 11 October 2023 for day VFR operations[7] at an aircraft time in service of 7,144.4 hours. The current maintenance release was not recovered from the helicopter and was likely lost or destroyed during the accident sequence. The last 2,200‑hour airframe inspection was completed in February 2021 at 6,457.9 hours, which was 686.5 hours prior to the latest maintenance release. The ATSB’s logbook review did not identify any anomalies with the maintenance of the helicopter.

Environmental conditions

Local observations

At the town of Katherine, located about 48 NM north-north-west of Bloodwood Station, moonset was at 1403, sunset was at 1900 and last light was at 1924. On the afternoon of the accident there were bushfires in the area and back-burning had been initiated on the southern boundary of the Wyworrie Station, between the Wyworrie and Gorrie homesteads, to provide fire breaks. The terrain between the Wyworrie and Gorrie homesteads was described as flat and therefore unlikely to cause terrain shielding effects.

One of the pilot’s relatives at Wyworrie described the conditions at the time the helicopter flew past Wyworrie Station as 'very dark, no moon, and complete nightfall'. There were 2 fires to the south of the Wyworrie homestead with one located about 1 km south of the homestead. The bushfire smoke resulted in hazy conditions, such that it became dark earlier, and the direction the helicopter was flying was towards the smoke. The relative reported that at nightfall the wind became calm, which stopped the smoke drifting away and resulted in it hanging in the air.

The pilot’s other relative at Wyworrie, who was also a helicopter pilot, reported the only hazard that night was the smoke and recalled ‘there was a lot of smoke’. They had flown the same flightpath in the past and reported that the pilot ‘would have flown into the smoke’ based on the direction the helicopter was tracking as it flew past Wyworrie. They also reported that the pilot could have flown around the smoke but that it might have been too dark for the pilot to see the smoke.

The owner of Bloodwood Station reported there was no smoke at their homestead when the helicopter departed but observed a lot of smoke in the vicinity of Gorrie Station later in the night after the search was initiated. The manager of the Larrizona Station reported that the conditions were ‘really dark, no moon’ and that there was smoke blowing across the road between the Larrizona and Gorrie Stations.

Bureau of Meteorology

A graphical area forecast for the NT was issued by the Bureau of Meteorology at 1337 on the day of the accident and valid for the period from 1430 until 2030. The forecast divided the NT into 3 areas: area A, B and C. The location of the accident site was near the boundary of area A, which extended northward, and area B, which extended southward. There was no smoke forecast for area A. However, area B included a forecast for isolated[8] areas of visibility reduced to 5,000 m in smoke below 10,000 ft. Satellite imagery provided by the Bureau of Meteorology revealed smoke in the vicinity of the accident site was present throughout the day. A comparison of the daytime and night-time satellite images revealed the smoke likely became more widespread in the vicinity of the accident site after last light.[9]

Collision and wreckage information

The ATSB did not attend the accident site and the following information was derived from analysis of imagery provided by the NT Police. The imagery included ground-based photography and filming, and aerial photography and filming with a remotely piloted aircraft system.

Accident sequence

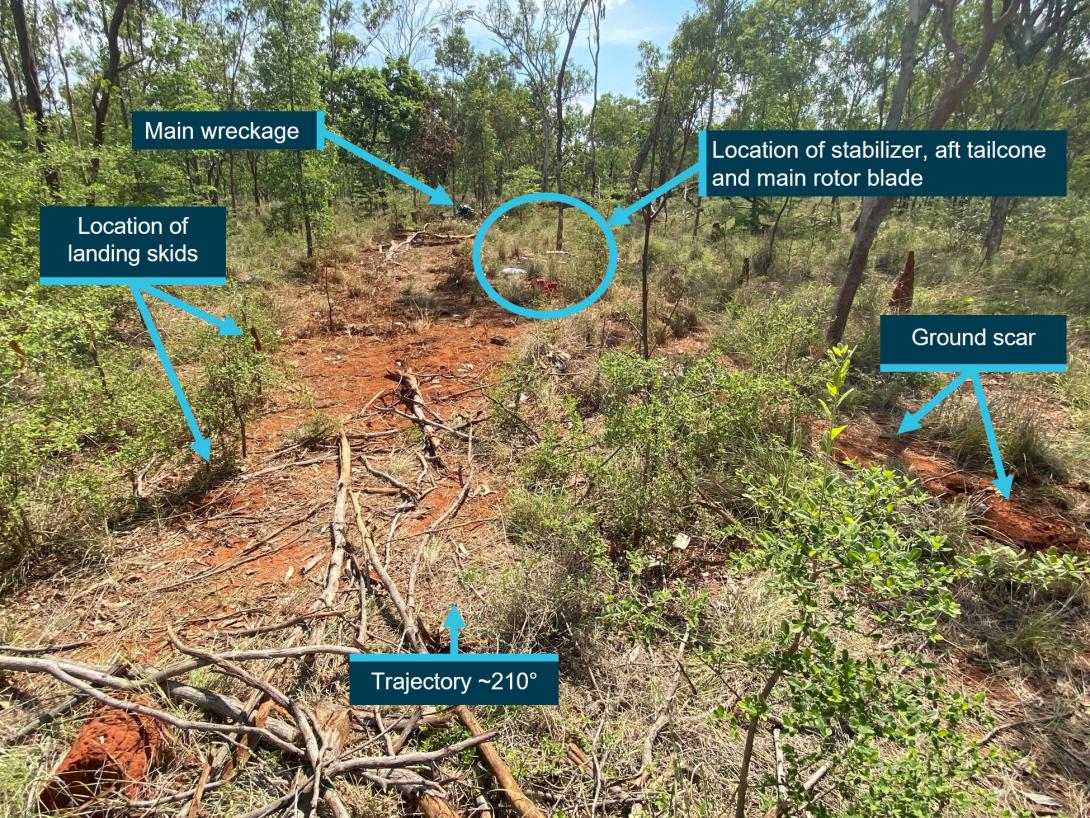

The helicopter initially struck a tall tree, breaking tree branches and the cabin perspex, before impacting the ground. The direction of travel was about 210° (True). There was a prominent ground scar on the right side of the main wreckage trail, which exhibited a pattern of multiple ground strikes and was the start of the ground impact sequence. Two broken sections of the landing skids were found buried in the ground on the left side at the start of the main wreckage trail, one after the other with the second one protruding. They were estimated by the police to be about 8 ft apart (Figure 3).[10] The fronts of the landing skids were otherwise not identified among the images of landing skid debris in the wreckage.

Figure 3: Location of broken landing skids

Source: Northern Territory Police, annotated by ATSB

Following the initial ground contact, subsequent ground contact caused the helicopter to become significantly fragmented. The vertical and horizontal stabilizer assembly separated from the tailcone and were found on the right side of the wreckage trail, followed by the aft section of the tailcone with the tail rotor and driveshaft, followed by one of the main rotor blades. The entire cabin forward of the vertical firewall was destroyed. The trail from the initial tree strike to the main wreckage was estimated by the ATSB to be about 46 m in length (Figure 4).[11]

Figure 4: View of the wreckage trail

Source: Northern Territory Police, annotated by ATSB

The helicopter battery was found beyond the main wreckage at a distance estimated by the police to be about 15-20 m. An outboard section of the attached main rotor blade separated from the rotor blade and was estimated by the police to be about 75 m beyond the main wreckage. The main wreckage was consumed by a post-impact fire that was contained within the immediate area. There was no evidence of fire in the trail leading to the main wreckage site or on any parts separated from the airframe outside the immediate area.

Engine and fuel systems

The engine was lying on its left side (as installed) in the main wreckage. No engine controls were identified. The alternator and exhaust system were present. Of the 2 uppermost cylinders, the induction system was present and the upper and lower spark plugs were noted as fitted with the ignition leads attached. The engine starter ring gear, lower sheave and 2 engine oil coolers were identified in the wreckage and the cooling fan fibreglass shroud had collapsed around the fan assembly. The fuel tanks were not identified and were likely consumed in the post‑impact fire. The engine carburettor, air filter housing and related ducting were not identified.

Flight control system

A review of the images of the helicopter flight control system identified that the pitch link to the separated blade spindle was present, intact, and securely attached to the swashplate rotating ring. The opposite pitch link was not identified. Of the 3 control tubes attached to the swashplate stationary ring, the rod ends were identified and found to be securely attached. The control tubes were consumed in the fire but the jackshaft was identified. The pilot’s collective and cyclic controls were not identified but a portion of the cyclic torque tube and aft bellcrank was identified with control rod ends attached and hardware present. The tail rotor pitch links, and the pitch change mechanism at the tail gearbox were present and connected.

Rotor systems and drive train

One of the main rotor blades separated in the accident sequence while the other remained attached to the rotor head. The detached blade showed evidence of upward and aft bending that presented as a significant upward bend at the blade root and buckling of the trailing edge (Figure 5). The detached blade also lost a small portion of the trailing edge section; however, the blade tip was present and attached. The opposite (attached) main rotor blade exhibited trailing edge buckling and had lost a section of the outer portion including the tip (found about 75 m beyond the main wreckage), which was consistent with the blade striking an object. A strike mark in the shape of a main rotor blade profile was present on the left side of the tailcone and the intermediate flex coupling exhibited significant tension, which indicated the tailcone was probably separated by a main rotor blade strike after the initial ground impact.

Figure 5: Aft tailcone and bent main rotor blade

Source: Northern Territory Police, annotated by ATSB

The tail rotor gearbox and tail rotor assembly were attached to the tailcone and both tail rotor blades were attached to the hub with one blade exhibiting signs of a strike and the other significantly bent near the root. The drive train from the engine to main gearbox was identified with the input yoke, forward flex plate and clutch yoke found to be fastened together. The upper sheave was identified but the drive belts were not visible and likely consumed by fire. The tail rotor drive shaft and damper bearing assembly were identified in the tailcone.

Instruments and electrical systems

The lower instrument panel was located near the start of the wreckage trail. The upper instrument panel was located closer to the main wreckage with the airspeed indicator gauge. The needle in the airspeed indicator indicated about 88 kt. The engine ignition switch was identified and found with the key broken off in the barrel. The position of the switch was aligned with ‘BOTH’, indicating that both magnetos were selected, which is the normal position for flight.

Survivability

During the search and rescue process, the Australian Maritime Safety Authority produced a Timeframe for Survival Briefing Report. The report noted that the pilot was physically fit with no known heart conditions or long-term health issues and there were no mental or physical health concerns held by the pilot’s immediate family, which was consistent with the pilot’s last medical examination report. The pilot had managed the cattle station property since 1988 as well as neighbouring properties at various points in time and was therefore familiar with the area. The impact-activated emergency locator transmitter had been removed from the helicopter and the pilot carried a portable emergency beacon and a satellite phone. The helicopter was fitted with a global positioning system and ultra-high frequency radio and the pilot reportedly always carried a 2 L bottle of water in the helicopter and a larger container of water if mustering.

The NT forensic pathologist post-mortem examination report found that the overall pattern of injuries was consistent with forces sustained in a helicopter accident from a ‘substantial height and/or at high-speed.’ The ATSB’s review of the impact and wreckage trail was consistent with the pathologist’s conclusion and the accident was not considered to be survivable.

Previous accidents

Collision with terrain occurrences at night are often fatal and the ATSB has investigated several Robinson R22 accidents in which the helicopter was not equipped to be operated at night and the pilot was not qualified to fly at night. This accident was the third in the last 3 years. The previous 2 accidents were:

- Collision with terrain involving Robinson R22, VH-LOS, 36 km south of Ramingining, Northern Territory, on 14 November 2022

- Collision with terrain involving Robinson R22 Beta II helicopter, VH-HKC, 87 km north of Hughenden Aerodrome, Queensland, 11 February 2021

In 2012, the ATSB published an aviation research report (AR-2012-122) Avoidable Accidents No. 7 - Visual flight at night accidents: What you can’t see can still hurt you (atsb.gov.au), which included a review of 36 night flying accidents (of which, 27 were fatal) in Australia from 1993 to 2012 that occurred under either visual or instrument conditions. According to the report:

Of the 26 accidents during night visual conditions, half involved a loss of aircraft control, most likely due to the influence of perceptual illusions caused by the lack of visual cues. The other half involved controlled flight into terrain (CFIT), where the pilot probably did not know of the terrain’s proximity immediately before impact.

Civil Aviation Safety Authority advisory circular

In 2022, the Civil Aviation Safety Authority published version 1.1 of their night VFR rating advisory circular, AC 61-05 v1.1 - Night VFR rating (casa.gov.au), in which they described the safety case for the night VFR rating as follows:

Night flying accidents are not as frequent as daytime flying accidents; however, significantly less flying is done at night. Statistics indicate that an accident at night is about two-and-a-half times more likely to be fatal than an accident during the day. Further, accidents at night that result from controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) or uncontrolled flight into terrain (UFIT) are very likely to be fatal accidents. Loss of control by pilots flying under NVFR [night VFR] has been a factor in a significant number of fatal accidents.

The hazards and risks section of the advisory circular included the expected dark adaptation time for the human eye, which can take up to 30 minutes to fully adjust to darkness. It also described ‘black-hole’ operations as those conditions where there are insufficient external visual cues present to allow for aircraft orientation.

There were several sections of the advisory circular specific to night helicopter operations, which included the following information:

6.3.4 Rotorcraft operations

6.3.4.1 The pilot must be able to maintain the rotorcraft's orientation by use of visual external cues as a result of lights on the ground or celestial illumination, unless the aircraft is fitted with an autopilot, stabilisation system or is operated by a two-pilot crew.

6.3.4.2 When flying at night, it is good practice to select a route via high visual cueing areas, such as a populated or lighted area, or a major highway or town that will make navigation easier and offer more options in the event of an emergency.

6.5.5 Requirements for flight

6.5.5.2 In order to conduct operations safely and legally at night in a rotorcraft, the visual cueing environment must be accounted for in the planning and execution of NVFR [night VFR] rotorcraft operations.

Safety analysis

On 7 December 2023, moonset and last light at Katherine, NT, were at 1403 and 1924 respectively, which resulted in dark night conditions. At 1930, the pilot departed Bloodwood Station on a private flight to return home to Gorrie Station. The weather at Bloodwood was described as a clear, moonless night, and the track from Bloodwood to Gorrie was away from the major population centres that might otherwise have provided an artificially illuminated horizon.

A review of the pilot’s qualifications and aircraft logbook found the pilot and helicopter were limited to day VFR conditions. The pilot had some night flying experience but the helicopter was not equipped for night flight, specifically, there was no artificial horizon. Without the necessary instruments and training it was very unlikely that the pilot would have been able to orientate the helicopter without external visual references.

The pilot’s relatives at Wyworrie Station observed the helicopter fly past their homestead, at about 1945, where conditions were very dark with smoke from fires between Wyworrie and Gorrie. This was consistent with the estimated flight time between Bloodwood and Wyworrie and indicated that despite not being night VFR rated, the pilot was able to operate the helicopter at night under clear conditions. However, the relatives also noted the helicopter was flying into the smoke as it tracked towards Gorrie and at this time the pilot was heard making a radio call to the caretaker at Gorrie, questioning if the hangar lights were on. This was a source of lighting the pilot would likely have been able to see under clear conditions from overhead Wyworrie and the caretaker thought that the pilot sounded disorientated. The last radio call from the pilot, dark night conditions, change in weather conditions at nightfall and satellite imagery of the distribution of smoke after last light all suggested the pilot inadvertently flew into the smoke.

The helicopter wreckage was later found about 7.5 km south of the Wyworrie Station homestead, and 6.1 km north-north-east of the Gorrie Station homestead, where it had collided with terrain on a track consistent with the direction towards Gorrie. The forecast reduction in visibility to 5 km in smoke likely resulted in the lights at both Gorrie and Wyworrie being beyond visual range for the pilot at the location of the accident site. It is also possible the pilot’s eyesight may not have fully adapted to the darkness at the time of the accident and the ATSB could not determine whether the pilot was wearing their prescription night driving glasses.

The ground scar to the right of the main wreckage path and discovery of the broken landing skids buried in the ground on the left side of the main wreckage trail followed by the lower instrument panel indicated that the helicopter was likely in a nose down, right roll attitude when it collided with terrain. The discovery of the helicopter battery about 20 m beyond the main wreckage, and an outboard section of one of the main rotor blades about 75 m beyond the main wreckage, indicated a high energy collision in terms of both the helicopter airspeed and rotor speed. The evidence from the witnesses, forecast conditions and the impact and wreckage trail indicated the pilot likely lost external visual references in smoke on a dark night after passing the Wyworrie Station homestead and became spatially disorientated, which resulted in the helicopter colliding with terrain uncontrolled at high speed.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition, ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the VFR into smoke on a dark night and collision with terrain involving Robinson R22, VH-DLD, 112 km south‑south‑east of Tindal Aerodrome, Northern Territory on 7 December 2023.

Contributing factors

- The pilot departed after last light for a return home flight on a dark night but was not qualified to fly at night and the helicopter was not equipped to be flown at night.

- It is likely that the pilot became spatially disorientated after the helicopter entered a smoke plume under dark night conditions during the return home flight, which resulted in uncontrolled flight into terrain.

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included the:

- Australian Maritime Safety Authority

- Bureau of Meteorology

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- maintenance organisation for VH-DLD

- Northern Territory Office of the Coroner

- Northern Territory Police

- Robinson Helicopter Company

- witnesses.

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Robinson Helicopter Company

- United States National Transportation Safety Board.

A submission was received from the Civil Aviation Safety Authority. The submission was reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the draft report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2024

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] The owner of Bloodwood Station received a phone call at 1930, as the helicopter departed.

[2] Last light: the time when the centre of the sun is at an angle of 6° below the horizon following sunset. At this time, large objects are not definable but may be seen and the brightest stars are visible under clear atmospheric conditions. Last light can also be referred to as the end of evening civil twilight.

[3] The hangar lighting included internal floodlights and 2 external spotlights, 1 pointed downward onto the pad and the other pointed upward.

[4] It was likely that the continued presence of smoke, degree of damage and accident site located among trees hampered the location of the wreckage.

[5] The pilot was re-issued with a commercial pilot licence (helicopter) on 6 May 2015 in accordance with the new flight crew licencing regulations.

[6] Visual flight rules (VFR): a set of regulations that permit a pilot to operate an aircraft only in weather conditions generally clear enough to allow the pilot to see where the aircraft is going.

[7] The helicopter was fitted with instrument lighting but it was not equipped with the minimum instrument requirements for night VFR flight. Specifically, there was no attitude indicator installed to provide the pilot with an artificial horizon.

[8] Isolated: Individual features which affect or are forecast to affect up to 50% of an area.

[9] A night-time temperature inversion could trap smoke and prevent it dispersing but the data was not available for this location to confirm the presence of an inversion.

[10] Paced out by NT Police onsite. The distance between the R22 landing gear skids is 6 ft 4 inches.

[11] This distance was estimated by scaling and overlaying imagery on Google Earth.