The ATSB is investigating the collision with terrain of a Cirrus SR22, registered VH-MSF, near Gundaroo, New South Wales on 6 October 2023.

The ATSB has completed the evidence collection, analysis and report drafting and is currently in the internal review phase.

The final report will be released at the conclusion of the investigation. Should a critical safety issue be identified during the course of the investigation, the ATSB will immediately notify relevant parties, so that appropriate safety action can be taken.

Preliminary report released 15 December 2023

This preliminary report details factual information established in the investigation’s early evidence collection phase, and has been prepared to provide timely information to the industry and public. Preliminary reports contain no analysis or findings, which will be detailed in the investigation’s final report. The information contained in this preliminary report is released in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003.

The occurrence

Prior to departing, the pilot had submitted a flight notification to Airservices Australia, detailing their planned track to Armidale, operating under the instrument flight rules.[1] The pilot was provided an air traffic control clearance to track to Armidale via their flight planned route at an altitude of 10,000 ft above mean sea level.

At 1437 local time, the aircraft departed Canberra. Soon after take-off, the pilot was transferred to, and established radio communication with the approach controller, reporting that they were on climb through 3,400 ft (to their assigned cruise altitude) and turning left onto their assigned radar heading of 070°.

A short time later, the controller instructed the pilot to turn left onto a heading of 010° and the pilot completed readback of the instruction. About 1 minute 30 seconds later, the controller cleared the pilot to resume their own navigation and track direct to waypoint[2] ‘CULIN’. The pilot completed readback of that instruction, which was the last transmission received from the aircraft. Figure 1 illustrates the ground track of the aircraft departing Canberra while assigned radar vectors and the direct track to CULIN.

During the flight, data was being transmitted by the aircraft’s Automatic Dependent Surveillance Broadcast (ADS-B) equipment.[3] A review of that data indicated that the aircraft was climbing through about 7,000 ft as it turned to track towards CULIN. During that turn, the groundspeed increased, over a period of about 30 seconds, from about 110 kt (204 km/h) to 135 kt (250 km/h).

Climbing above 7,500 ft, the data indicated the aircraft’s groundspeed had started to reduce, at an approximately linear rate, with a reduction of about 22 kt (41 km/h) over a 65-second period. At that time, the data showed a relatively constant rate of climb generally between 550–750 ft/min.

Passing through 8,500 ft, a further 21 kt reduction in groundspeed occurred over a 14-second period, which was accompanied by a short increase in the reported rate of climb. The data indicated the groundspeed then started to increase as the aircraft entered a slight descent.

Over the next 4 minutes, the aircraft’s track varied up to 35° and the groundspeed fluctuated between 90 kt and 120 kt (167–222 km/h). During this period, the altitude was generally increasing although at a varying rate, with shorter periods where the altitude and reported rate of altitude change indicated that the aircraft had started to descend. Several people at locations along the aircraft’s flight path during this time reported hearing noises that they described as a rough running or surging light aircraft engine.

Twelve minutes after take-off, the aircraft was about 25.5 km north-north-east of Canberra, at an altitude of about 10,000 ft, when it abruptly departed from controlled flight and descended steeply towards the ground. Two eyewitnesses in the local area described seeing the aircraft at a low altitude, descending rapidly with its nose pitched down and rotating like a corkscrew. One of the witnesses stated that they heard the engine running rough and then stop just before the accident. The other eyewitness was seated on a tractor with the engine running and did not hear the aircraft engine.

The aircraft collided with terrain (at a ground elevation of about 2,250 ft) and was destroyed by impact forces and a post-impact fire. All occupants were fatally injured. The eyewitness on the tractor was the first responder on the scene and notified the emergency services.

Figure 1: Ground track of VH-MSF from take-off to the accident site

Source: OpenStreetMap with ADS-B data from Airservices Australia and aggregated ADS-B data from FlyRealTraffic.com, annotated by the ATSB

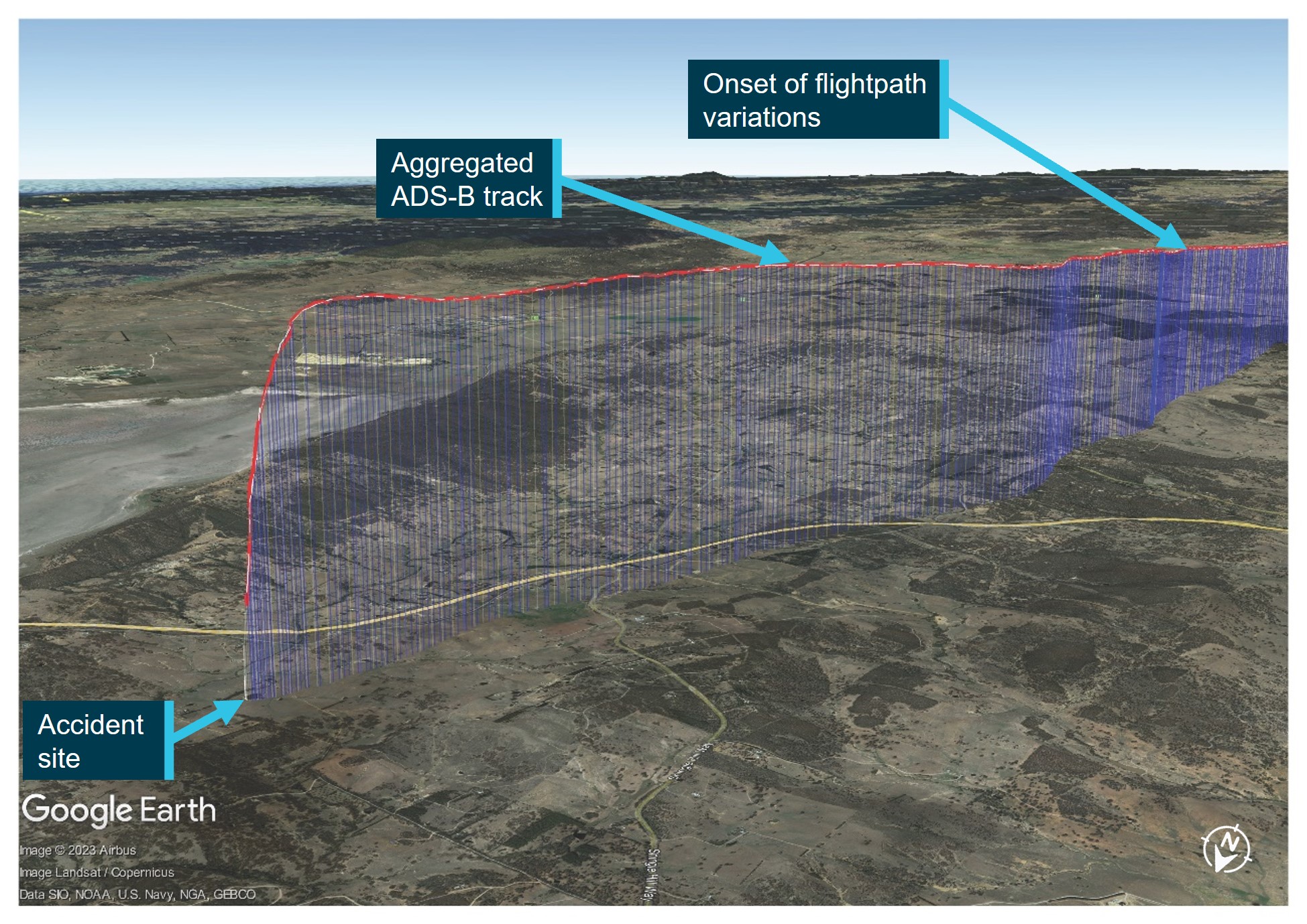

Figure 2 depicts the aircraft’s altitude and ground track during the last part of the flight after the pilot was cleared to resume their own navigation and includes the position where the flightpath variations commenced.

Figure 2: Aggregated ADS-B data for VH-MSF, looking back along the flightpath

Source: Google Earth, with ADS-B data from Airservices Australia and aggregated ADS-B data from FlyRealTraffic.com, annotated by the ATSB

Context

Pilot information

The pilot held a Private Pilot Licence (Aeroplane), issued in 1985, and with class ratings for single‑ and multi-engine aeroplanes. The pilot was initially issued with a command instrument rating for single-engine aeroplanes in 1987 and their most recent flight review, on 29 August 2023, was an instrument rating proficiency check with an endorsement for multi-engine aeroplanes. The pilot had reportedly accumulated about 800 hours total flying experience.

The pilot held a Class 2 Aviation Medical Certificate valid to 22 October 2023 with 2 restrictions. A requirement for reading and distance vision correction to be worn while flying and that a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) system be used for the sleep period before flying. The pilot was reported to have been well rested before the flight and was utilising the CPAP while sleeping as required.

Aircraft information

The Cirrus Design Corporation SR22 is a low wing aircraft with 4 seats and a single piston engine driving a constant speed propeller. It has a ballistic parachute system fitted as standard. The aircraft (S/N 0153) was manufactured in the United States in 2002 as a G1 model. It was purchased as a second-hand aircraft in the United States in 2017 and then placed on the Australian register with the registration VH-MSF. Since then, it has been operated by its owner for private use, community service flights and private charter operations.

Recent maintenance included the completion of a 100-hour/annual inspection and maintenance release issue on 9 November 2022 at an aircraft time-in-service of 2,558.9 flight hours. The Cirrus Airframe Parachute System (CAPS) was inspected, and the parachute and rocket motor assemblies were replaced due to time expiry in January 2023.

The limitations section of the Cirrus SR22 Pilot’s Operating Handbook stated ‘Aerobatic manoeuvres, including spins, are prohibited.’ The note associated with the manoeuvre limits stated, ‘Because the SR22 has not been certified for spin recovery, the CAPS must be deployed if the airplane departs controlled flight.’

The United States Federal Aviation Administration approved the Cirrus SR22 for flight into icing conditions in 2009 based on the introduction of an optional anti-ice system for the wings, windshield, propeller, and vertical and horizontal stabilizer leading edges. This was known as a flight into known icing approval. As VH-MSF was manufactured in 2002, which predated this approval, the aircraft owner confirmed there was no anti-icing system fitted. Therefore, the aircraft was prohibited from flying into known icing conditions. This limitation was documented in both the Pilot’s Operating Handbook and also stated in current aviation regulations.

Meteorological information

Canberra Airport is located near the intersection of 4 areas in the grid-point wind and temperature chart for New South Wales. The chart issued at 1105 on 6 October 2023 and valid from 1400, indicated the freezing level overhead Canberra was forecast to be at about 7,000 ft with south‑westerly winds at 6-17 kt. The graphical area forecast for ‘NSW-East’, issued at 0913 on 6 October 2023, was valid for the period 1000-1600. Canberra Airport and the accident site were in the south of subdivision D1. The forecast for area D, which included subdivision D1, had the following conditions:

- visibility greater than 10 km, scattered cumulus/stratocumulus cloud[4] from 5,000 ft to 8,000 ft with broken tops to 10,000 ft in D1

- visibility reduced to 3,000 m in isolated showers of rain, with broken stratus cloud from 1,500 ft to 4,000 ft and broken cumulus/stratocumulus cloud from 4,000 ft to above 10,000 ft

- freezing level[5] of 5,000 ft in the south and 8,000 ft in the north

- cumulus and stratocumulus cloud implies moderate turbulence

- cloud above the freezing level implies moderate icing.[6]

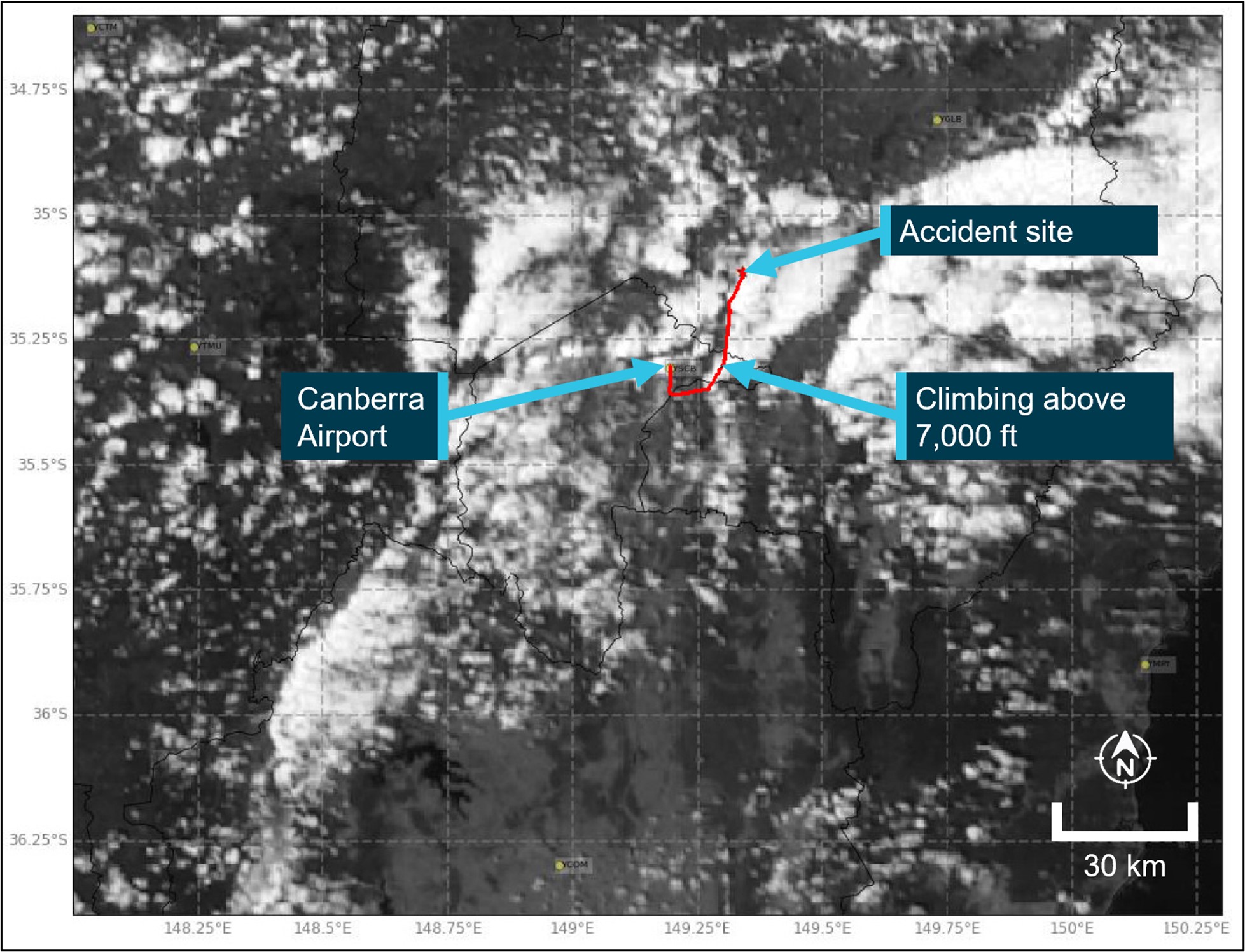

Figure 3 illustrates the ADS-B ground track of the aircraft, overlaid on a satellite image of cloud in the local area at 1450, about 1 minute after the accident.

Figure 3: Aircraft flight track overlaid on satellite image

Note: This image depicts the Himawari-8/9 visible satellite imagery just after the accident, including the ADS-B track of VH-MSF and the position which the aircraft climbed above 7,000 ft.

Source: Satellite image originally processed by the Bureau of Meteorology from the geostationary satellite Himawari-8/9 operated by the Japan Meteorological Agency and modified by ATSB and using aggregated ADS-B data from FlyRealTraffic.com

Recorded information

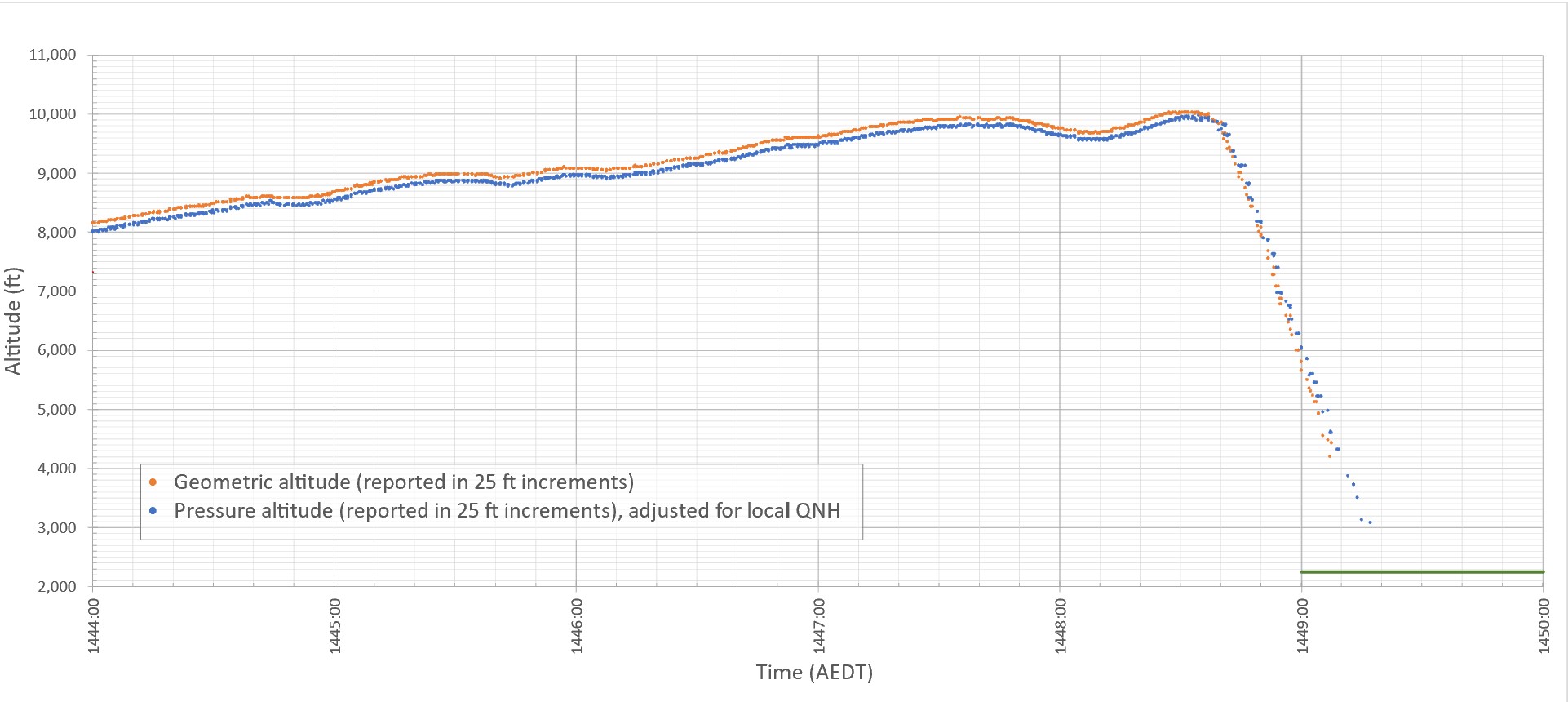

Figure 4 depicts ADS-B altitude data broadcast from the aircraft during the final 5 minutes of the flight. This includes the several relatively minor altitude excursions/descents, together with the larger altitude excursion/descent that occurred immediately before the departure from controlled flight.

Preliminary analysis of the aircraft’s reported groundspeed, together with sources of meteorological data[7] indicated that the aircraft’s calibrated airspeed[8] was about 70 kt (130 km/h) at the time it departed from controlled flight.

The Pilot’s Operating Handbook provided performance data for the aircraft, including information about the aircraft’s aerodynamic stall[9] speeds. At the maximum take-off weight (1,542 kg), idle power and nil wing flap, the published wings-level stall speed was 67-69 kt (124–128 km/h) calibrated airspeed, depending on the centre of gravity position.[10] The Pilot’s Operating Handbook also indicated that the aircraft had conventional stall characteristics, and that power‑on stalls were marked by a high sink (descent) rate at full aft stick.

The altitude and reported rate of altitude change, indicated an accelerating rate of descent, that increased above 13,000 ft/min before reducing back towards 10,000 ft/min prior to the impact with terrain.

Figure 4: Aggregated ADS-B altitude data

Note: The green line at the bottom right corner of the plot depicts the elevation of terrain in vicinity of the accident site.

Source: ATSB, using aggregated ADS-B data from Airservices Australia and FlyRealTraffic.com

Site and wreckage information

The aircraft came to rest on a private property in an open field adjacent to a dam. Although post‑impact fire damage precluded examination of a significant proportion of the aircraft, inspection of the site and wreckage showed that (Figure 5):

- The impact marks and wreckage distribution indicated that the aircraft impacted with terrain upright, with a slight nose low attitude and with little forward momentum, suggestive of a spin.[11]

- All the aircraft’s extremities and flight controls were present in the immediate area of the accident site.

- There were no identified structural defects in the evidence available.

- The CAPS cover, deployment system and parachute were all located within the wreckage and had not been deployed before impact. However, based on the available evidence, the ATSB was unable to determine if an attempt had been made by the pilot to deploy the parachute system before the impact.

- The damage to the propeller blades indicated that the engine had low or no power at impact. It should be noted though, that spin recovery, icing, un-porting of fuel tank outlets in a spin, preparation for use of the parachute, and an engine mechanical issue could all be reasons for a power reduction.

Figure 5: Overview of the accident site

Source: ATSB

Further investigation

To date, the ATSB has:

- examined the aircraft and accident site

- recovered aircraft components

- interviewed relevant parties

- collected aircraft, pilot, and operator documentation

- conducted a preliminary analysis of flight track data.

The investigation is continuing and will include:

- examination of recovered aircraft components

- further review of aircraft, pilot, and operator documentation

- analysis of pilot medical information

- an assessment of the aircraft’s performance based on flight track data

- analysis of meteorological information

- a review of similar occurrences.

Should a critical safety issue be identified during the course of the investigation, the ATSB will immediately notify relevant parties so appropriate and timely safety action can be taken.

A final report will be released at the conclusion of the investigation.

Acknowledgements

The ATSB would like to acknowledge the significant assistance provided during the initial investigation response by the New South Wales Fire Service, the accident site property owner and the local community of Gundaroo.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2023

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] Instrument flight rules (IFR): a set of regulations that permit the pilot to operate an aircraft in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC), which have much lower weather minimums than visual flight rules (VFR). Procedures and training are significantly more complex as a pilot must demonstrate competency in IMC conditions while controlling the aircraft solely by reference to instruments. IFR-capable aircraft have greater equipment and maintenance requirements.

[2] The pilot’s flight notification comprised a series of defined geographic positions (waypoints) via which the pilot intended to navigate the aircraft to Armidale. The flight notification’s first waypoint after departing Canberra was CULIN.

[3] The ADS-B equipment transmitted flight data that enabled air traffic service providers to track aircraft when operating outside coverage of conventional air traffic control radar. Airservices Australia recorded the transmissions received by their network of ground-based ADS-B receivers. That data could also be received by other aircraft with suitable equipment and privately-operated ground-based equipment, feeding information to flight tracking websites.

[4] Cloud cover: in aviation, cloud cover is reported using words that denote the extent of the cover – ‘scattered’ indicates that cloud is covering between a quarter and a half of the sky and ‘broken’ indicates that more than half to almost all the sky is covered.

[5] The freezing level is the height in feet above mean sea level where the air temperature is 0 °C.

[6] The rate of accumulation of moderate icing is such that even short encounters become potentially hazardous and the use of de-icing/anti-icing equipment or a flight diversion is necessary.

[7] This includes data from the Bureau of Meteorology’s vertical wind profiler at Canberra Airport, wind and temperature data from recorders on an aircraft descending into Canberra close to the time of the accident and data from a similar aircraft that passed overhead Canberra a short time before.

[8] Airspeed was not a parameter transmitted by the aircraft’s ADS-B equipment. The calibrated airspeed was derived from the ADS-B recorded groundspeed and track using the available measurements of wind velocity, atmospheric pressure and temperature.

[9] Aerodynamic stall: occurs when airflow separates from the wing’s upper surface and becomes turbulent. A stall occurs at high angles of attack, typically 16˚ to 18˚, and results in reduced lift.

[10] The actual stall speed on any given flight depended on a number of variable factors including the aircraft’s operating weight/centre of gravity, flap setting, engine power, bank angle and/or load factor.

[11] Spin: a sustained spiral descent of a fixed-wing aircraft, with the wing’s angle of attack beyond the stall angle.