Executive summary

What happened

On 6 July 2023, a pilot was conducting a navigational exercise in a Piper PA-28 (PA-28), registered VH-SFA and operated by Schofields Flying Club Limited, from Bankstown Airport with an intermediate stop at Shellharbour Airport, New South Wales. As the aircraft taxied for departure from Shellharbour, a Saab 340 (Saab), operated by Link Airways as flight FC251 from Brisbane, Queensland to Shellharbour, was on approach to land on runway 34.

After landing, the Saab was required to backtrack the runway due to a taxiway weight restriction. As the Saab crew lined up with the centreline to commence their backtrack, they observed the PA‑28 rolling on the runway towards them. They attempted to contact the pilot of the PA-28 via radio but were unable to make contact. To avoid a collision, they moved to the western edge of the runway. The pilot of the PA-28 detected the Saab ahead of them, and after initial hesitation, elected to continue the take-off. They tracked to the eastern side of the runway and passed over the left wing of the Saab at a height of approximately 150 ft.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that the pilot of the PA-28 assumed that the Saab would be vacating the runway via a taxiway at the end of the runway. They were not aware of the weight restriction on the taxiway and incorrectly assumed the runway would be clear for their departure.

The PA-28 pilot also used non-standard radio phraseology, which did not clearly state that they were entering the runway. The Saab crew re-stated their intention to backtrack on the runway, however, this transmission was not heard by the pilot of the PA-28 and they commenced their take-off.

The pilot of the PA-28 detected the Saab at a point where a rejected take-off was almost certainly possible, but due to hesitation and perceived handling difficulties, they elected to continue the take-off from an occupied runway.

What has been done as a result

Schofields Flying Club revised their admission procedures for students trained by other organisations and introduced procedures to increase oversight and standardise competency assessments among flight instructors. Link Airways reviewed their policy and guidance for operations into Shellharbour and encouraged crew to refamiliarise themselves with CASA guidance for radio procedures in non-controlled airspace.

Safety message

When operating at a non-towered airport, pilots are responsible for maintaining separation between one another. This practice of ‘self-separation’ relies on pilots making clear radio broadcasts when necessary to prevent traffic conflicts and paying attention to transmissions being made by other pilots sharing the same airspace. Additionally, an effective lookout is crucial to identify conflicts that may not be identified through normal radio broadcasts.

Pilots need to use information from both inside and outside the aircraft to maintain situational awareness and to inform their own decisions. This can include the use of traffic displays from sources such as automatic dependent surveillance broadcast (ADS‑B) data. When threats are not detected early, the time and flexibility for making decisions can be greatly reduced and safety can be compromised.

The ATSB SafetyWatch highlights the broad safety concerns that come out of our investigation findings and from the occurrence data reported to us by industry. One of the safety concerns is Reducing the collision risk around non-towered aerodromes.

The investigation

| Decisions regarding the scope of an investigation are based on many factors, including the level of safety benefit likely to be obtained from an investigation and the associated resources required. For this occurrence, a limited-scope investigation was conducted in order to produce a short investigation report, and allow for greater industry awareness of findings that affect safety and potential learning opportunities. |

The occurrence

On 6 July 2023, the pilot of a Piper Aircraft Inc. PA-28-181 (PA-28), registered VH-SFA and operated by Schofields Flying Club Limited, was conducting a return solo navigation training flight from Bankstown Airport, New South Wales. The planned flight involved a touch-and-go landing at Shellharbour with a full stop landing at Goulburn, New South Wales before returning to Bankstown.

The PA-28 departed Bankstown at 0931 local time, arriving in the Shellharbour common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF) broadcast area (see the section titled Shellharbour Airport) at 1000. The pilot recalled that the Shellharbour airspace was very busy, and that they conducted a go‑around during their first approach due to traffic congestion. After conducting a circuit, the pilot elected to conduct a full stop landing in order to make use of the facilities and at around 1010, parked the PA-28 on the regular public transport (RPT) apron (Figure 1).

During this time, a Saab 340B (Saab), registered VH-VED and operated by Link Airways as flight FC251, was enroute to Shellharbour from Brisbane, Queensland. At 1041, while on descent, the flight crew broadcast on the CTAF that the aircraft was at 30 NM inbound to the airport. The Saab ground crew observed the PA-28 in the parking bay that had been allocated to the Saab and advised the pilot, over the radio, that an aircraft was inbound for that bay.

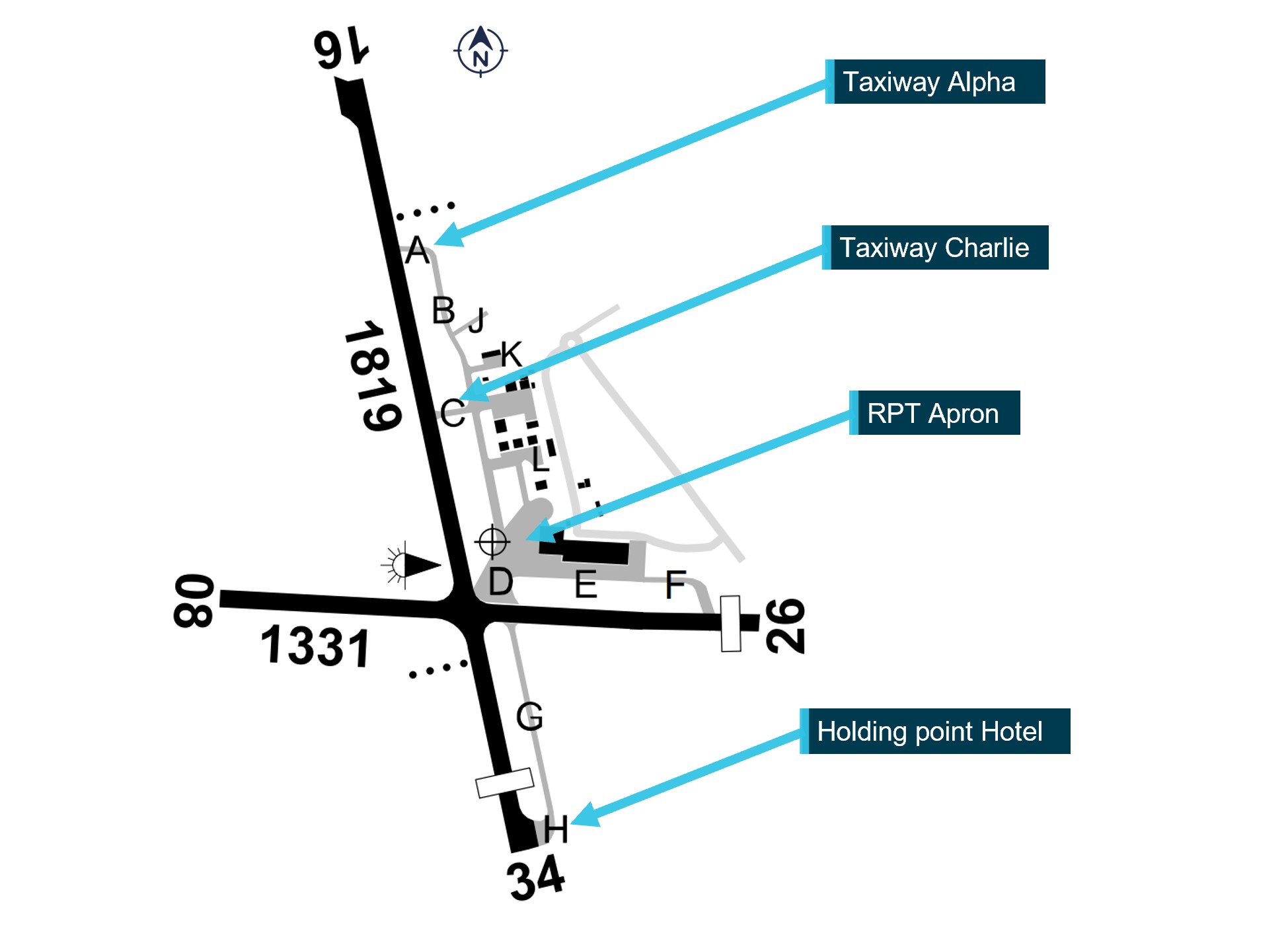

Figure 1: Shellharbour Airport layout

Source: En Route Supplement Australia, annotated by the ATSB

There were multiple VFR[1] aircraft in the Shellharbour CTAF area and the pilot monitoring (PM)[2] in the Saab made a series of broadcasts to other aircraft to organise separation and sequencing for their arrival. At 1051, after flying a circuit, the Saab turned onto a 3-mile final for runway 34.[3] At 1052, the pilot of the PA-28 made a radio broadcast advising they were taxiing for runway 34. Neither of the Saab flight crew recalled hearing this transmission. At 1053, the Saab flight crew made a radio broadcast, advising that they would be backtracking on the runway and subsequently landed on runway 34.

The PA-28 pilot taxied to, and held, at holding point Hotel (Figure 1) where they observed the Saab land and commence a turn to the right. Being unaware of the intended backtrack, they incorrectly assumed that the Saab would exit the runway on taxiway Alpha and taxi to the RPT apron. They then diverted their attention to other traffic in the circuit.

At 1054, after identifying a gap in the traffic, the PA-28 pilot broadcast that they were entering the runway using the non-standard phraseology ‘turning on runway 34’. The PM in the Saab, in the turn to backtrack the runway, immediately replied, advising that they would be backtracking runway 34, however the PA-28 pilot did not hear this transmission. The PA‑28 pilot reported that, with the large number of aircraft in the circuit they felt pressured to commence the take-off as soon as possible and forgot to make a rolling call prior to commencing their take-off run. They further stated that as the aircraft accelerated past 50 kt, and towards the rotation speed, they saw the Saab appear to re-enter the runway at taxiway Alpha.

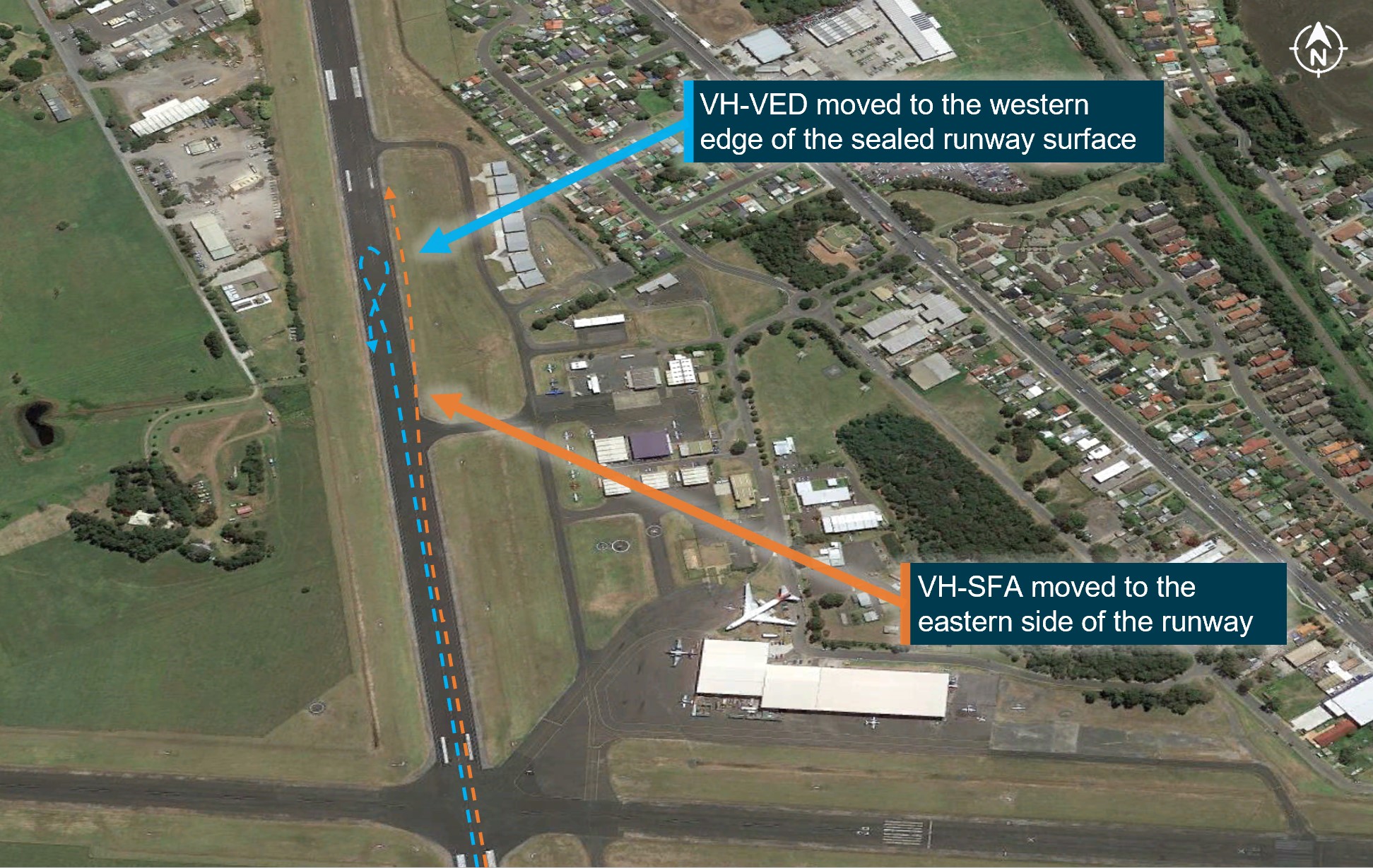

The pilot flying (PF) in the Saab advised that they ensured the landing lights were left on to aid in detection while on the runway. They also stated that, as right circuits were required when using runway 34, they made the reversal turn to the right on the runway to enable them to view the traffic in the circuit. As they realigned with the runway centreline to commence the backtrack, the PF noticed the PA-28 appeared to be rolling on the runway towards them. The PM attempted to contact the pilot of the PA-28, however, other aircraft in the circuit made broadcasts about this time, possibly over transmitting the call by the PM, and the transmission from the Saab was not heard by the pilot of the PA-28. In order to minimise the risk of collision with the approaching aircraft, the PF taxied the Saab to the western side of the sealed runway surface (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Aircraft avoiding action

The dashed lines show the approximate paths over the ground of each aircraft. The track of VED is based on recorded ADS-B data. The track of SFA is based on pilots’ statements.

Source: Google Earth, annotated by the ATSB

The PA-28 pilot, seeing the Saab on the runway ahead of them, initially hesitated. They advised they had never conducted a rejected take-off during their training and reported being unsure of the expected braking performance and the handling behaviour when using rudder steering.

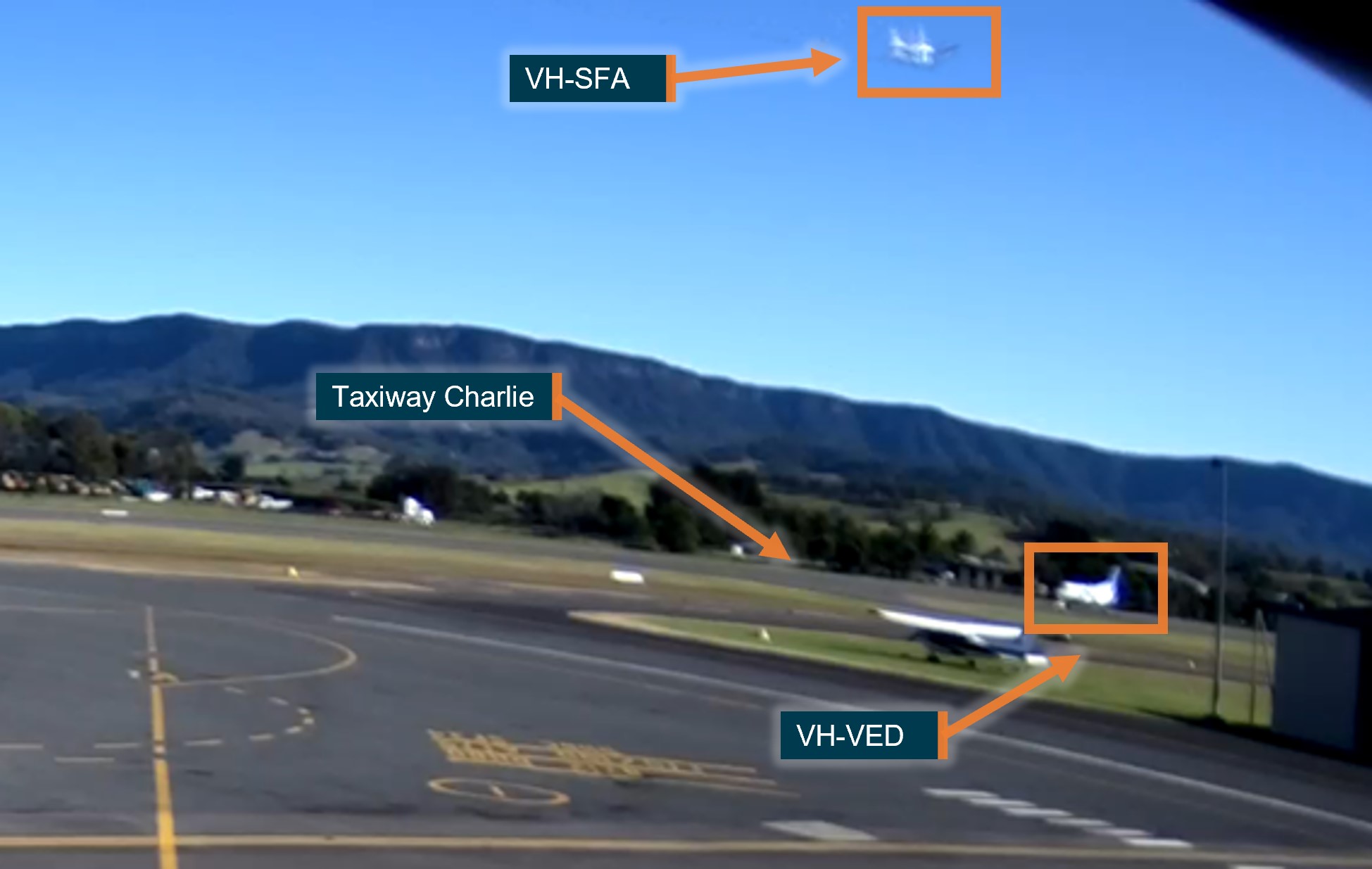

During the period of hesitation, the aircraft continued to accelerate towards the rotation speed of 60 kt. The pilot then assessed that the distance between the 2 aircraft was sufficient to continue the take-off. Additionally, they perceived that any attempt to stop the aircraft on the runway remaining was not assured and may have resulted in a ground collision. Based on the avoiding action taken by the Saab crew, they continued the take-off and rotated prior to the runway intersection, before slowly veering to the eastern side of the runway (Figure 2) and passing approximately 150 ft over the left wing of the Saab (Figure 3).

Figure 3: CCTV footage

Source: Shellharbour Airport CCTV. Annotated by the ATSB

Context

VH-SFA pilot training

The pilot commenced flight training with the flying school in January 2023 after obtaining their recreational pilot licence (RPL) with another training school. English was not their first language, but they had demonstrated the required fluency and competency on the radio to obtain this licence. The pilot had accrued approximately 110 hours total time, 22 hours of which was as pilot in command. A review of their training records indicated that they had flown with 6 different instructors for the 14 flights since commencing with the flying school. They had recently been approved to commence solo navigation training to obtain their private pilot licence (PPL). The occurrence flight was the third solo navigation flight completed by the pilot.

Various comments had been made in the training records regarding inconsistencies in their procedural rigour, times of reduced situational awareness and the use of non-standard radio calls and phraseology.

The flying school confirmed that aborted take-off practice was delivered as part of the RPL syllabus of training, and as such had not been covered in the pilot’s training with them. However, a review of the pilot’s training file from their previous training provider indicated that the pilot had been assessed as achieving the required competency during the emergency circuit lessons in the RPL syllabus in November 2021, where rejected take-offs were conducted from simulated engine failures during the take-off run.

Planned navigation exercise

The exercise was originally planned via Bathurst, however the weather forecast along this route included low cloud over the Blue Mountains. The supervising instructor, responsible for signing out solo students that day, recognised this and changed the planned route to avoid the low cloud. The forecast weather along the revised navigation route was favourable for flight under the visual flight rules, with good conditions at Shellharbour for the aircraft’s scheduled time of arrival.

This was the student’s fourth visit to Shellharbour during their training; however, they had never stopped there before. All previous visits had involved touch-and-go landings or circuit training with an instructor. As the flight plan only included a touch-and-go landing, the taxiways were not briefed prior to the flight.

Shellharbour Airport

Shellharbour Airport (Figure 1) has two intersecting sealed runways 16/34 and 08/26. Runway 34 was in use at the time of the occurrence and had a 0.1% down slope to the north. The view of the entire runway from the threshold marker was clear of obstructions with good visibility (Figure 4).

Figure 4: View from the runway 34 threshold

Source: Shellharbour aerodrome operator.

The Enroute Supplement Australia (ERSA) facilities page detailed local procedures and restrictions. A note under ‘Local traffic regulations’ detailed a maximum weight restriction of 5,700 kg for taxiways Alpha and Bravo which run parallel to runway 34. As a result of this weight limitation, heavier aircraft such as the Saab 340 were required to backtrack along the runway to the intersection of the runways where they could then vacate via taxiway Delta for the RPT apron (Figure 1). The flying school’s internal investigation of this occurrence identified that the student was unaware of this limitation and was briefed by an instructor on their return to Bankstown.

The Shellharbour CTAF operates on a discreet frequency of 127.3. This frequency is the primary means of communication between aircraft operating in the vicinity of the aerodrome with the aerodrome receiving a mix of general aviation and regular public transport aircraft. Both the PA-28 pilot and the Saab flight crew described the airspace as typically being very busy when the weather was good. This was probably due to the number of flying school aircraft that use Shellharbour for circuit training and as an intermediate waypoint on navigation exercises.

Communication

Operations in the vicinity of non‑controlled aerodromes require flight crew to be aware of other aircraft that may be operating in the area by maintaining a listening watch on the radio and, if necessary, making radio broadcast to organise collision avoidance and sequencing. Communication is key to developing awareness, and guidance has been produced to standardise radio transmissions and phraseology to assist with effective and efficient radio communication.

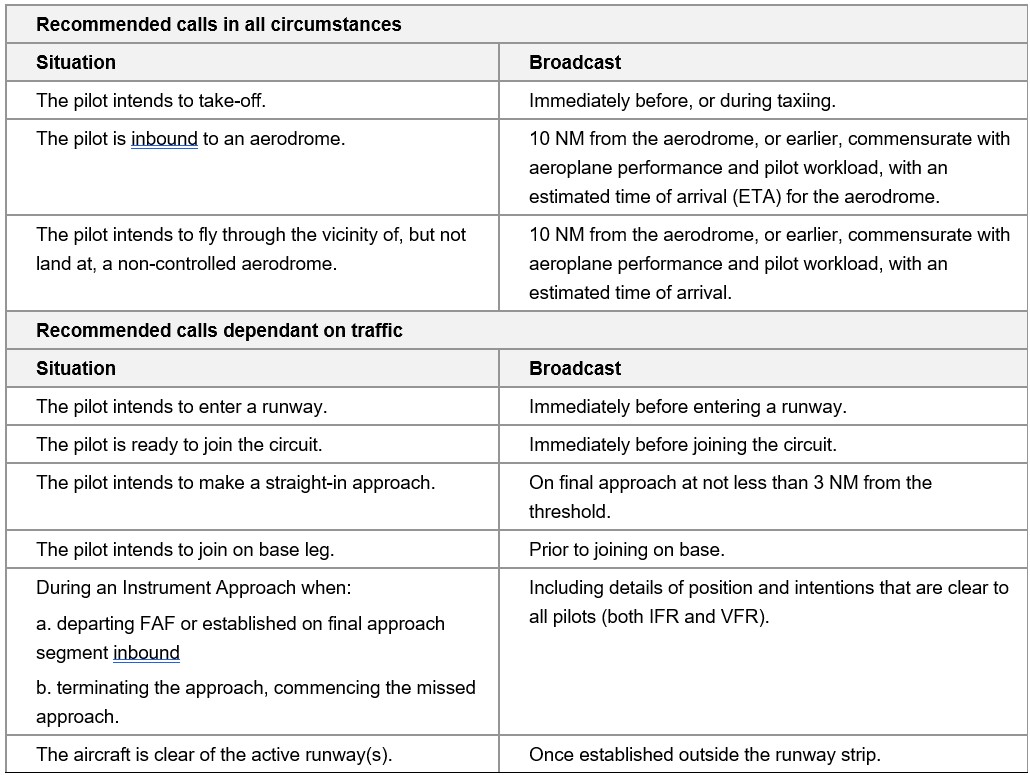

Civil Aviation Safety Regulations 1998 Part 91 – Manual of Standards Chapter 21 listed the broadcast and reporting requirements for non-controlled CTAF airspace (Table 1).

Table 1: CTAF – prescribed broadcasts

| Situation | Frequency | Requirement |

| When the pilot in command considers it reasonably necessary to broadcast to avoid the risk of a collision with another aircraft. | CTAF | Broadcast |

In addition to this prescribed broadcast requirement, guidance in Civil Aviation Advisory Publication 166-01 v4.2 Operations in the vicinity of non-controlled aerodromes; and the Visual Flight Rules Guide produced by the Civil Aviation Safety Authority provided a list of recommended radio broadcasts to mitigate the risk of a collision in the CTAF (Table 2).

Table 2: Recommended positional broadcasts in the vicinity of a non-controlled aerodrome

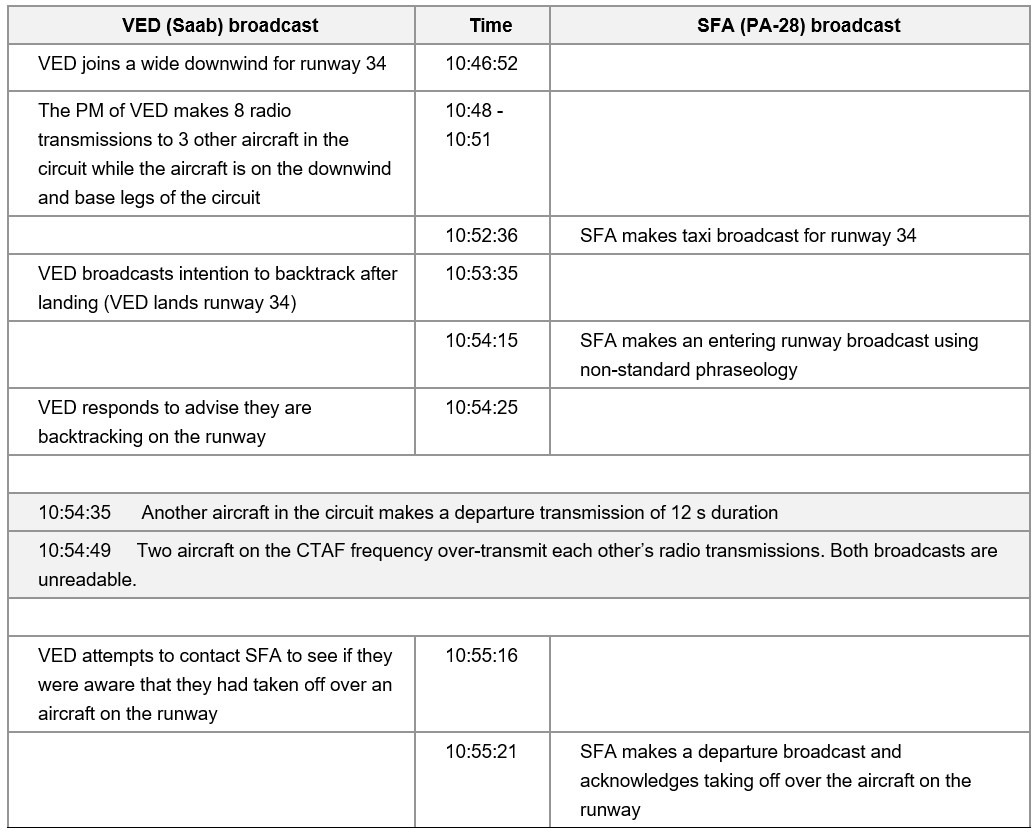

A recording of the CTAF frequency at the time of the occurrence was obtained and provided a record of what broadcasts were made by the Saab flight crew and the PA-28 pilot. A summary of the key communication events appears in Table 3.

Table 3: Shellharbour CTAF radio broadcasts

During the time the Saab commenced their approach and the PA-28 departed, a number of radio transmissions were unreadable, probably due to different aircraft making simultaneous radio broadcasts. Significantly, one of these transmissions coincided with the report of the PM in the Saab trying to alert the pilot of the PA-28 to the conflict on the runway. Additionally, the crew of both aircraft reported missing radio transmissions from the other aircraft involved in the occurrence and having limited opportunity to make broadcasts due to the number of aircraft in the circuit.

A review of the radio broadcasts made around the time of the occurrence confirmed that in addition to the 2 occurrence aircraft on the runway, there was 1 aircraft departing from mid‑downwind overhead the field, and 3 other aircraft in the circuit.

Aircraft performance calculations

The estimated braking performance for a Piper PA-28 Archer II was used to determine the approximate distance to reject a take-off in the prevailing conditions. Calculations were based upon actual weather observations recorded by the Bureau of Meteorology at Shellharbour, pilot interviews, and the take-off and landing performance charts in the PA-28 Archer II pilot operating handbook (POH). To this calculation, the applicable landing safety factor recommended in CASA guidance material[4] was applied. The calculations are presented in Figure 5 and show the distance to accelerate to 50 kt and reject the take-off.

The point where the aircraft reached 50 kt and the PA-28 pilot first sighted the Saab was based on the interview with the pilot of the PA-28. Calculations were based on the aircraft commencing take-off from the threshold of runway 34 and not from runway entry at holding point Hotel. The pilot’s reported hesitation was not accounted for in this calculation.

Figure 5: Calculated braking performance in the event of a rejected take-off by VH-SFA

Source: Google Earth annotated by the ATSB.

Safety analysis

A review of the radio broadcasts that were made on the CTAF frequency supported the pilots’ assessment that the Shellharbour CTAF was busy on the day of the occurrence, increasing their workload and hampering effective radio communication. In this environment, both crew missed radio transmissions from the other aircraft involved in the occurrence. The use of non-standard phraseology from the PA-28 pilot as they entered the runway was unclear in its intentions and open to interpretation. Despite this, the Saab crew appear to have understood the intent as they immediately restated that they were backtracking the runway. Significantly, this transmission was missed by the PA-28 pilot who commenced the take-off without making a rolling call or confirming with the Saab crew that they were clear of the runway. It was determined that in the context of a busy radio frequency there was little opportunity for the Saab crew to make an additional broadcast due to transmissions made by other aircraft around this time.

Despite the impact on communication, there were multiple opportunities for the pilot of the PA-28 to identify that the Saab had not vacated the runway. They recalled observing the Saab commence a right turn on the runway, indicating they had an unobstructed view of the aircraft from the holding point and threshold of runway 34. However, they did not continue to monitor the Saab and diverted their attention to the traffic in the circuit. The decision to expedite the take‑off was influenced by self-imposed time pressure due to the traffic density. The pilot was aware that they should not have taken off from an occupied runway, indicating that they would not have done so if they had detected the conflict.

Once the pilot of the PA-28 detected the Saab on the runway, their response further added to the potential for a collision. Based on the descriptions provided by the crew of where each aircraft was located on the runway at the time the conflict was detected by the pilot of the PA-28, braking performance calculations showed that there was most likely enough room to stop in the distance available.

Although the pilot advised they had never conducted a rejected take-off during their training, training records indicated the required competencies had been demonstrated, however this was 19 months prior to the occurrence. These sessions involved the student rejecting a take-off in response to a simulated engine failure during the take-off roll. While the student had been assessed as competent, it could not be determined if the training scenario provided an accurate assessment of the pilot’s threat identification and decision-making skills. There was no record of an additional rejected take-off training assessment. In practice, the manipulation of controls to reject a take-off is similar to those required to stop an aircraft following normal and maximum performance landings. It is therefore unlikely that the pilot would have encountered control characteristics that they were not familiar with.

Student records indicated the PA‑28 pilot was familiar with Shellharbour circuit procedures, having previously flown there with instructors and on a solo navigation exercise. However, as these previous flights did not include full-stop landings, it is reasonable that taxiways not intended to be used as part of this exercise were not discussed during the pre-flight briefing. However it also meant that the pilot was unaware that larger aircraft, such as the Saab, could only access the apron by backtracking along the runway.

While detail of the taxiway restrictions are provided in the local regulations section of the Enroute Supplement Australia facilities page, a specific warning entry (such as already published for another airport hazard) that alerts inexperienced pilots to the possibility that taxiway restrictions require larger aircraft to backtrack along the runway could:

- prompt pilots to check that aircraft are actually clear of the runway prior to commencing their own take-off

- reduce the likelihood of misidentifying the turn to backtrack as the aircraft vacating the runway.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the runway incursion involving a Piper PA-28, VH-SFA, and Saab 340, VH-VED, at Shellharbour Airport, New South Wales on 6 July 2023.

Contributing factors

- The PA-28 pilot did not hear the backtracking broadcast from the Saab, reducing their awareness of the conflict on the runway.

- Although the PA-28 pilot observed the Saab commence a turn at the end of its landing roll on the runway, the pilot incorrectly assessed the aircraft had vacated the runway prior to commencing their take-off.

- The PA-28 pilot continued the take-off from an occupied runway and departed overhead the Saab that was backtracking the runway.

Other factors that increased risk

- The busy traffic environment at the time of the occurrence impacted the effectiveness of radio communication and increased both flight crews’ workload.

Safety actions

| Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence. |

Safety action by Schofields Flying Club

Schofields reviewed their procedures for onboarding students trained by other organisations. All students are now required to commence training from the beginning of the relevant syllabus, or, after a formal assessment by the Head of Operations, they may be considered to enter the syllabus at a higher level. Additional safety action was taken to reduce the number of students allocated to each instructor, improving oversight, and the introduction of competency standards discussions during fortnightly flight instructor meetings.

Safety action by Link Airways

Following an internal review of the occurrence, Link Airways revised company guidance for operations into Shellharbour. Due to the workload and identified potential for conflict with VFR aircraft in the circuit, the requirement to conduct an instrument approach for all arrivals or a 10 NM final approach leg has been removed. Flight crew are reminded to make all required radio calls to maintain situational awareness and to review the CASA publication BE HEARD, BE SEEN, BE SAFE – Radio procedures in non-controlled airspace.

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- the occurrence pilots

- Schofields Flying Club

- Link Airways

- Bureau of Meteorology

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- the aircraft manufacturer

- Shellharbour Airport

- video footage of the flight

- aircraft ADS-B data.

References

Piper Aircraft Corporation (1975). Piper Cherokee Archer II Pilot’s Operating Handbook.

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- the occurrence pilots

- Schofields Flying Club

- Link Airways

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

Submissions were received from:

- Link Airways

- Schofields Flying Club

The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2023

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] Visual flight rules (VFR): a set of regulations that permit a pilot to operate an aircraft only in weather conditions generally clear enough to allow the pilot to see where the aircraft is going.

[2] Pilot Flying (PF) and Pilot Monitoring (PM): procedurally assigned roles with specifically assigned duties at specific stages of a flight. The PF does most of the flying, except in defined circumstances, such as planning for descent, approach and landing. The PM carries out support duties and monitors the PF’s actions and the aircraft’s flight path.

[3] Runway number: the number represents the magnetic heading of the runway.