Executive summary

What happened

On 26 December 2022, a Stoddard Hamilton Aircraft Glasair Super II FT, registered N600, departed Temora, for a private flight to Wedderburn aircraft landing area, New South Wales. On arrival at Wedderburn, N600 conducted a landing and go-around on runway 17. During the go‑around, N600 failed to achieve sufficient climb performance and impacted terrain about 2.7 km to the south-west of Wedderburn. The aircraft was destroyed, and the two pilots on board were fatally injured.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that N600 conducted an approach to land on runway 17 with a quartering tailwind and subsequently conducted a go-around after touch down. For reasons that could not be determined, N600 did not achieve a sufficient climb performance after take-off which led to a collision with terrain.

The ATSB also found that both pilots on board did not have recent experience in single-engine, automotive engine conversion, amateur-built aircraft or the Glasair in general.

Additionally, the pilots elected to operate the aircraft from Bankstown to Temora for the aircraft’s first flight in Australia, even though the special flight authorisation did not permit operations over built-up areas.

It was also found that N600 was fitted with propeller pitch change rocker switches on the left and right side of the throttle which were reversed in orientation for each flight crew member. This increased the risk that a pilot flying from the right seat could operate the propeller pitch change opposite to the intended selection.

Safety message

Pilots intending to operate amateur-built aircraft should be aware of the potential differences in systems and controls to that of conventional type-certified aircraft. They should also consider transition training onto the same aircraft type, or aircraft with similar design features and performance capabilities.

Pilots attempting to conduct post-maintenance proving flights in amateur-built aircraft are urged to be proficient in the specific aircraft emergency operations, particularly those related to partial power failures. It is also prudent to select an appropriate aerodrome and benign weather conditions to conduct familiarisation flights, to safely expand their operational experience.

When a formal flight plan is not lodged, leaving a flight note with a responsible person who is able to notify the appropriate authorities should the flight become overdue is also an important safety consideration.

Understanding the safety implications of regulatory permissions is vital so that experimental aircraft operations do not adversely affect the safety of third parties, such as other airspace users and people on the ground not associated with the operation of the aircraft.

The investigation

| Decisions regarding the scope of an investigation are based on many factors, including the level of safety benefit likely to be obtained from an investigation and the associated resources required. For this occurrence, a limited-scope investigation was conducted in order to produce a short investigation report, and allow for greater industry awareness of findings that affect safety and potential learning opportunities. |

The occurrence

On the morning of 26 December 2022, a Stoddard Hamilton Aircraft Glasair Super II FT, registered N600, was operated on a private flight under the visual flight rules (VFR)[1] from Bankstown to Temora, then onto Wedderburn, New South Wales. The aircraft was registered in the US, and this was the aircraft’s first flight in Australia, and its purpose was to reposition the aircraft to Wedderburn. The two pilots were both co-owners of the aircraft. Air traffic control audio recorded the aircraft departing Bankstown at about 1003 local time.

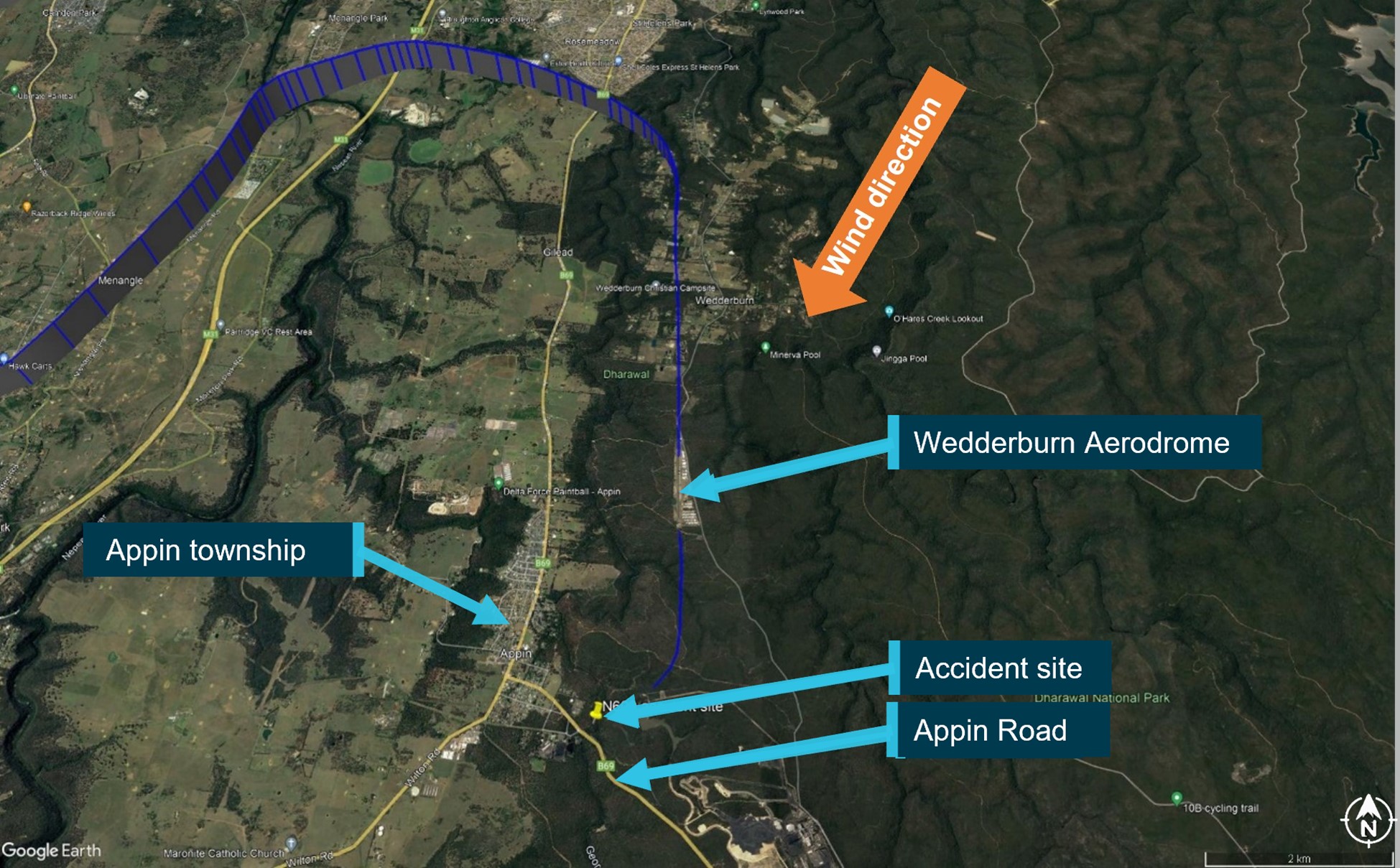

Flight tracking data (Figure 1) showed the aircraft being flown to Temora, landing at about 1133. The aircraft was then refuelled and conducted 2 circuits[2] before departing about an hour later for Wedderburn, which was expected to be its planned destination.

Figure 1: Flight tracking data from N600 on 26 December 2022

Source: Google Earth, ADS-B Exchange, FlightRadar24 and OzRunways, annotated by the ATSB

On arrival at Wedderburn, N600 was positioned on a wide circuit and landed on runway 17[3] at about 1452. The pilot then conducted a go-around[4] and the aircraft became airborne again.

Witnesses at Wedderburn observed the aircraft in a shallow climb, climbing just enough to clear rising terrain and trees at the end of runway 17. After clearing the trees, the aircraft disappeared from view below the ridgeline. About 2 minutes later, N600 collided with terrain about 2.7 km from the end of the runway, and about 150 m from Appin Road (Figure 2), about 1.4 km to the south‑east of Appin township.

The wreckage was consumed by a post-impact fire that also started a small bush fire. Both occupants were fatally injured.

Figure 2: ADS-B Exchange flight data showing the landing and go-around at Wedderburn aircraft landing area and the location of the collision with terrain

Source: Google Earth and ADS-B Exchange, annotated by the ATSB

Context

Pilot Information

For clarity, as there were 2 pilots on board N600, this report will identify them individually as ‘Pilot A’ and ‘Pilot B’. Witnesses confirmed that it was the intention that Pilot B would be in command for the flight from Temora to Wedderburn, however the exact seating positions and pilot in command for the accident flight are unknown due to the nature of the accident sequence.

To operate N600, a pilot was required to hold a valid US licence. Both pilots had obtained their United States Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) qualifications based on their previous Australian pilot licences and aviation medical certificates, however recent flight times and current FAA flight reviews were unable to be located.

Pilot A

Licencing and aeronautical experience

Pilot A was experienced in multi-engine fixed wing operations. They were operating N600 for the first time that day. Their FAA Private Pilot (Aeroplane) Licence was issued on 16 July 2009, however there are no records of an FAA single-engine aeroplane flight review since initial issue of the FAA licence based on their Australian qualification.

They held a Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) Air Transport Pilot (Aeroplane) Licence (ATPL(A)) that was re-issued on 22 January 2015. Recent pilot logbooks were unable to be located, however an electronic logbook file from December 2021 showed a total flying experience of 2,697 hours, of which almost 2,212 hours were in multi-engine aircraft.

The pilot had completed a CASA multi-engine flight review on 7 March 2021, which was valid to 31 March 2023. They had operated N600 for a number of ground runs in preparation for the first flight and was reported to have operated N600 from Bankstown to Temora on the day of the accident. The pilot held an RAAus pilot certificate, however it is unknown how much experience the pilot had with high performance single-engine aircraft. A witness identified that the pilot had previously flown a Glasair aircraft prior to the purchase of N600, however this was unable to be identified in the pilot’s logbook.

Medical

Pilot A held a valid CASA Class 2 aviation medical certificate, which was issued with restrictions that required distance correction and reading correction to be available whilst exercising the privileges of the licence.

Pilot B

Licencing and aeronautical experience

Pilot B was also experienced in multi-engine fixed wing operations, and operated N600 for the first time that day at Temora.

They held a CASA ATPL(A) that was issued on 29 April 1991. A recent pilot logbook was unable to be located, however the latest logbook identified (from July 1996 to August 2004) recorded a total flying experience of 6,156 hours, of which only 761 hours were in single-engine aircraft, with the last recorded single-engine flight in September 1999.

FAA records indicate that Pilot B received an FAA Commercial Pilot Certificate on 5 January 1990, based on their Australian licence however there are no records of an FAA single-engine aeroplane flight review since initial issue of the FAA licence based on their Australian qualification. CASA records indicate that the pilot had last completed a multi-engine aeroplane flight review on 7 March 2021 which was valid until 31 March 2023, there was no record of any single-engine flight reviews for either CASA or FAA licences.

Due to limited recorded flight hours for Pilot B, it was unable to be determined if the pilot had flown the aircraft type previously.

Medical

Pilot B previously held a CASA Class 2 aviation medical certificate which had expired on 18 November 2022. The Class 2 was issued with a restriction that reading correction must be available whilst exercising the privileges of the licence.

Aircraft Information

General

N600, serial number 2277, was a Stoddard Hamilton Aircraft Glasair Super II FT, amateur-built aircraft[5] constructed in the US. The aircraft was a high performance, conventional two-seat, single-engine, low-wing monoplane with tricycle undercarriage, built mostly of fibreglass. The aircraft was fitted with a Subaru EJ-25 automotive engine, modified for aviation use by NSI Propulsion Systems (later Maxwell Propulsion Systems). N600 had an initial Special Airworthiness Certificate issued on 30 April 2014. The first flight was conducted on 4 June 2014 in the US. About 59 hours flight time was accumulated before the aircraft was imported into Australia in 2021.

Prior to leaving the US, the aircraft was disassembled to facilitate shipping. Subsequently, upon arrival in Australia, significant work was undertaken to restore the aircraft to an airworthy condition.

Airworthiness and Maintenance history

The last recorded maintenance work in N600’s maintenance log was on 12 May 2016. Maintenance had continued to be recorded in the aircraft log up until disassembly on 28 April 2021.

After shipping to Australia in July 2021, N600 was reassembled in Bankstown by a CASA approved maintenance facility. When the maintenance facility was notified by the owners that N600 would remain on the US FAA register, an FAA certified Airframe and Powerplant (A&P) technician performed an airworthiness inspection in accordance with Federal Aviation Regulation 43, Appendix D.

During the disassembly process in the US, several electrical wiring looms were cut to facilitate the removal of the wing from the fuselage. An authorised repair facility performed the electrical reconnection and required inspections. No engine work was performed during the reassembly. The aircraft was released for service on 14 September 2022 by the FAA A&P.

No record of any periodic maintenance was identified since its original test flying and the aircraft had accrued about 59 hours total time in service.

Engine and propeller speed reduction unit

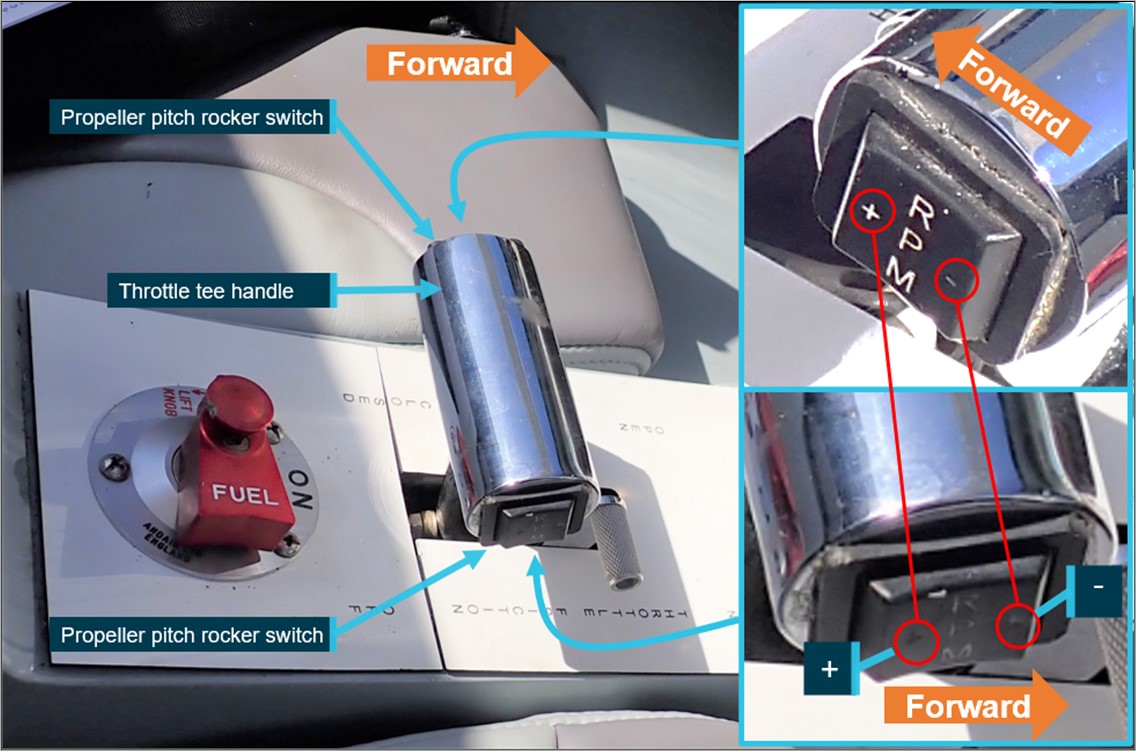

The Subaru EJ-25 is a 4-cylinder, liquid-cooled, fuel-injected automotive engine, fitted with a single electronic ignition. The engine throttle control was controlled by a single cockpit tee handle throttle, mounted in the centre console between the two seats, operating a cable to the fuel control unit (Figure 3).

The propeller speed reduction unit (PSRU) was mounted to the front side of the engine and had a speed reduction gearing of 2.1:1. The PSRU contained a sprag clutch to dampen engine harmonics.

Detailed laboratory examination of the engine and PSRU did not indicate any pre-impact or mechanical abnormalities that may have contributed to the accident. However, due to the fire affected engine components, much of the ignition and electrical system were consumed by the post-accident fire, and therefore were unable to be tested.

Propeller

N600 was fitted with a Maxwell Propulsion Systems CAP-220 two-blade, electric variable pitch propeller, with an alloy hub. The carbon fibre propeller blades were manufactured by Whirlwind Propellers.

Propeller pitch change control (Figure 3) was achieved with two rocker switches (one for each crew seat) mounted on either side of the throttle tee-handle lever, activating the electric pitch change motor. It took about 10 seconds to cycle between the course and fine pitch stops. The rocker switches were identical in their design and operation, in that when viewed directly on, the left side of the switch had the increase pitch selection (+), and the right side had the decrease pitch selection (-). This meant that if the switches were wired in accordance with the ‘+’ and ‘-‘ labelling, the switches would be actuated in opposite directions relative to each pilot’s seated position to achieve the desired propeller pitch change. The switch orientation and wiring was confirmed by the original aircraft builder as being wired correctly to the switch orientation when the aircraft was constructed.

Figure 3: Engine throttle tee-handle lever showing propeller rocker switches mounted to each side

Source: FAA A&P mechanic during inspection, annotated by the ATSB

There was no propeller pitch position indicator fitted to the aircraft. The pitch was set by using engine revolutions per minute (RPM) and manifold pressure indications. Pilot operation of the rocker switch electrically adjusted the propeller blades to achieve an optimal RPM and manifold setting for take-off, climb, cruise, approach, and landing.

ATSB performed a disassembly and examination of the electric in-flight adjustable propeller pitch motor and drive unit, which appeared in good condition. No evidence of pre-impact mechanical defects was identified. Some visible corrosion was found, however this was likely due to water used to extinguish the post-impact fire. The propeller pitch was set to about 19.5° and was consistent with other exemplar propeller pitch settings in the take-off configuration (fine propeller pitch) to allow greater acceleration and initial climb performance.

Fuel

N600 operated on aviation gasoline (AVGAS), and held 151 L in the main wing tanks, 76 L in the wingtip extensions, and an additional 26 L in the header tank. Each tank was fitted with a sump and a fuel drain. A fuel selector (Figure 3) was located on the centre console aft of the throttle. The selector had ‘off’ and ‘on’ positions only, and no option to select an individual tank to supply fuel to the engine.

Fuel records indicate that on 23 December 2022 100 L of AVGAS was uploaded to N600. It is unknown how much fuel N600 had on board at the time of departure from Bankstown, as a number of ground runs had been conducted prior to departing Bankstown for Temora.

On the day of the accident while at Temora, N600 was refuelled with 70.4 L of AVGAS before subsequently departing to Wedderburn.

Fuel residue was unable to be detected at the accident site due to substantial disruption to the airframe and subsequent post-impact fire. Therefore, the amount of fuel on board at the time of the accident was unable to be determined.

Meteorological Conditions

No significant rainfall was observed or recorded within 40 km of Appin around the time of the accident. Closed Circuit Television (CCTV) footage from Wedderburn showed clear skies and an easterly crosswind on runway 17, with a quartering[6] tailwind during the landing and subsequent go-round of N600.

Wreckage information

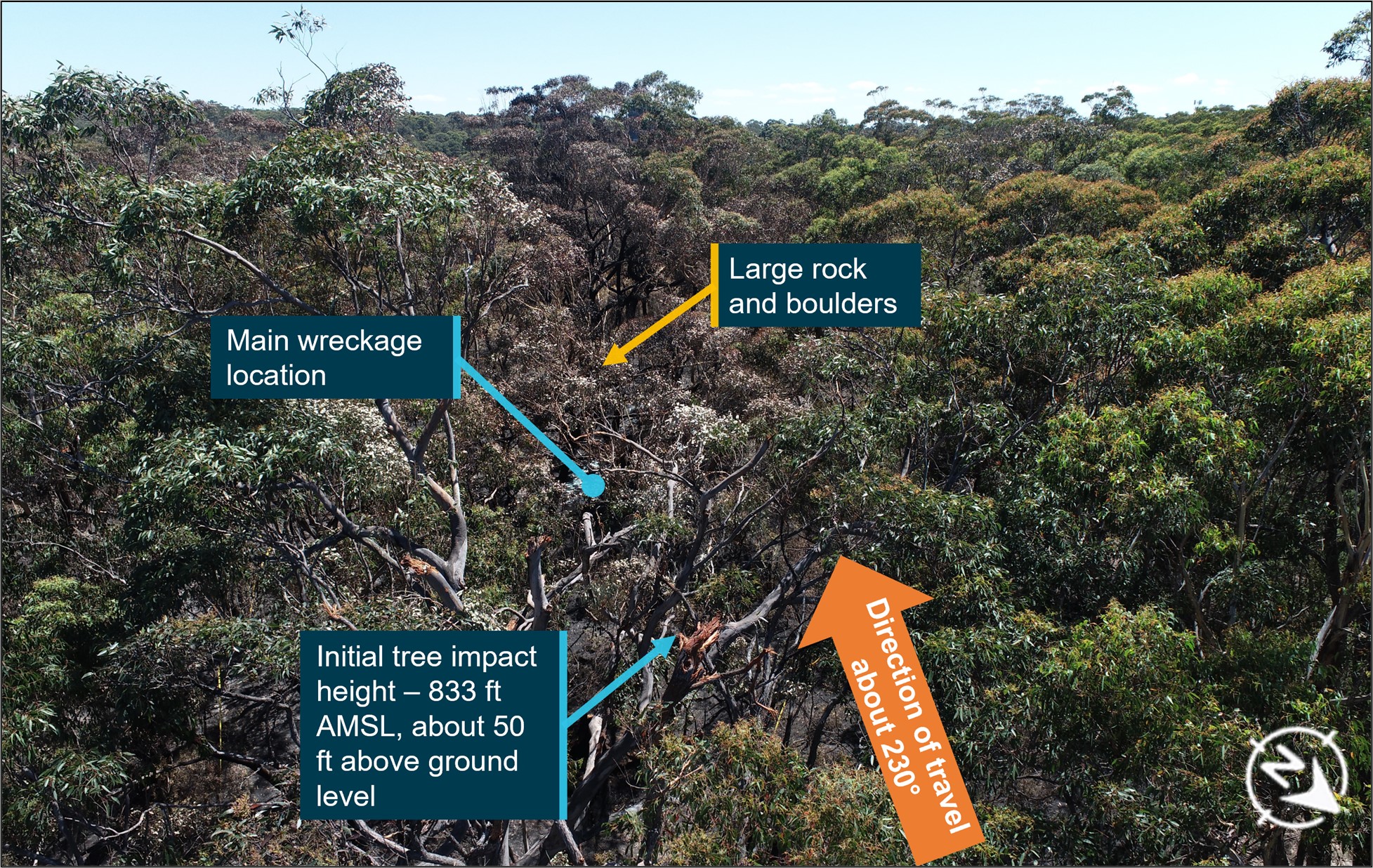

The accident site was located about 1.2 km to the south-east of Appin township (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Accident site

Image source: ATSB

N600 entered trees on an approximate heading of 237° and the first tree impact was about 50 ft above ground level (Figure 4) at 833 ft above mean sea level. The left-wing tip (fuel tank) was located to the left of that tree, and a piece of the upper left wing was to the right of the direction of travel, most likely as a result of initial tree impact. The aircraft then continued for about 45 m, hitting further trees, before impacting a large rock. The airframe was upright and facing opposite the direction of travel. The main wreckage was spread along a path of about 90 m and was heavily disrupted and fire affected.

Figure 5: Direction of travel N600

Image source: ATSB

During the accident sequence, the engine and propeller assembly had detached from the airframe and came to rest about 10 m further in the direction of travel, and was heavily affected by fire. Initial propeller contact with trees led to both blades separating from the hub. Most of the wreckage was contained within the fire zone with a small fragment of unburnt propeller blade located about 100 m from the initial tree impact point to the right of aircraft direction of travel.

Recorded data

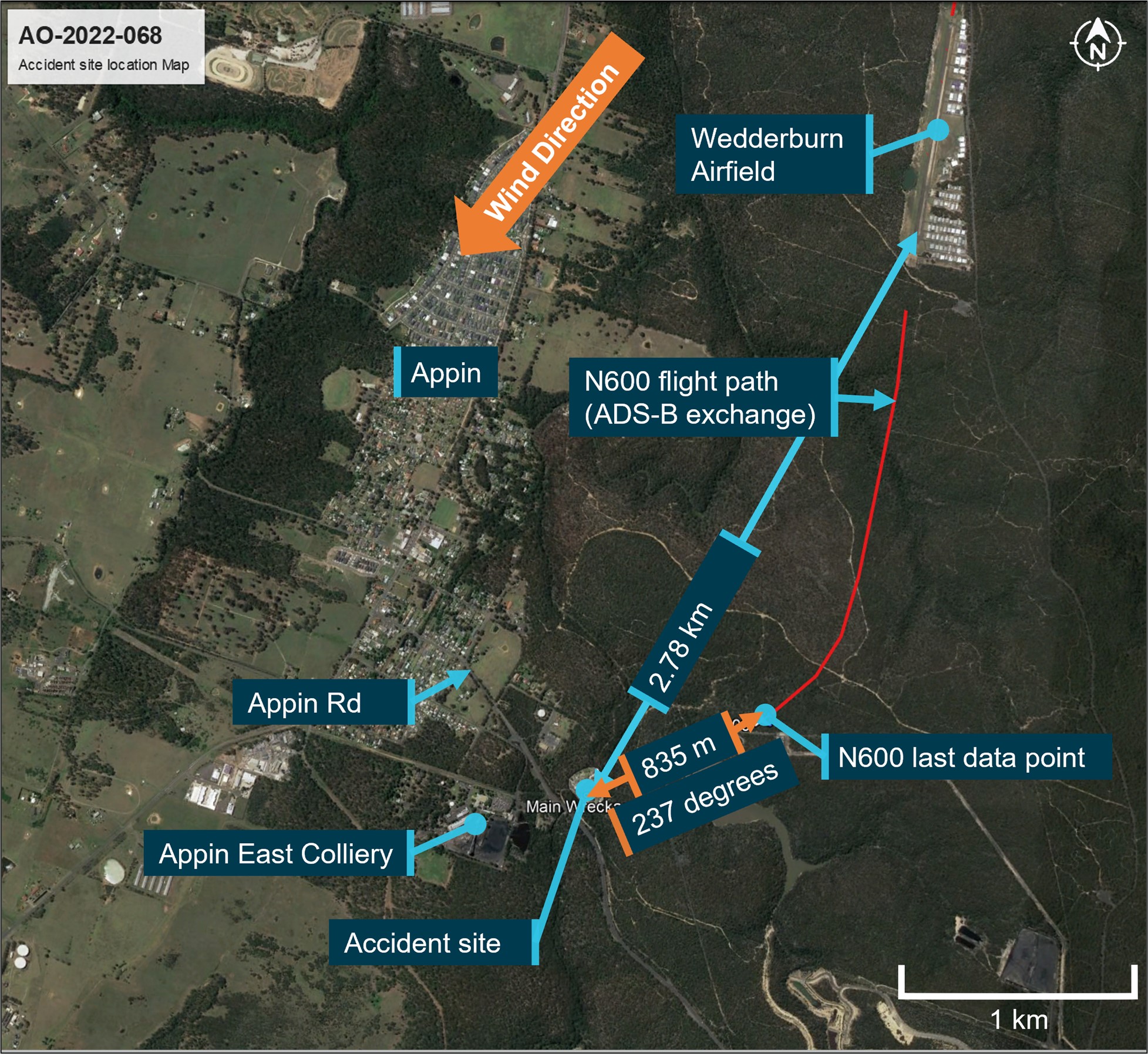

About 1 hour 23 minutes later, N600 joined a wide right downwind for runway 17 at Wedderburn. Wedderburn aircraft landing area has a single runway with a bitumen surface area of about 950 m in length. At about 1452, N600 touched down about 200 m into runway 17 at about 87 kt ground speed and rolled for about 50 m before becoming airborne again.

CCTV at Wedderburn showed the aircraft in a shallow climb, enough to just clear rising terrain and trees at the end of runway 17. After clearing the trees in the vicinity of the airfield, the aircraft then disappeared from CCTV view. Recorded data indicated that about 2 minutes later, N600 collided with terrain about 2.7 km from the end of the runway, about 150 m from Appin Road (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Final track N600

Image source: Google Earth and ADS-B Exchange, annotated by the ATSB

Other information

Amateur-built aircraft

Pilots and passengers of experimental aircraft in Australia accept the risk that the aircraft may not meet the same airworthiness safety standards as certified aircraft and operate these aircraft on the basis of informed participation.[7]

Transition to unfamiliar aircraft

General competency

For a pilot to operate a different aircraft type already covered by their licence category and class rating, they need only be satisfied that they are competent to conduct all normal, abnormal, and emergency flight procedures for the aircraft. They also need to be able to apply operational limitations, conduct weight and balance calculations, and apply aircraft performance data, including take-off and landing performance data, for the aircraft.

Guidance on transition

While no definitive Australian guidance provided advice on the transition of pilots to unfamiliar aircraft, the FAA advisory circular (AC) AC90-109A – Transition to Unfamiliar Aircraft (U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration, 2015) is a widely recognised and utilised publication providing a sound basis to consider the hazards of transitioning to unfamiliar types of aircraft, whether certified or experimental amateur-built.

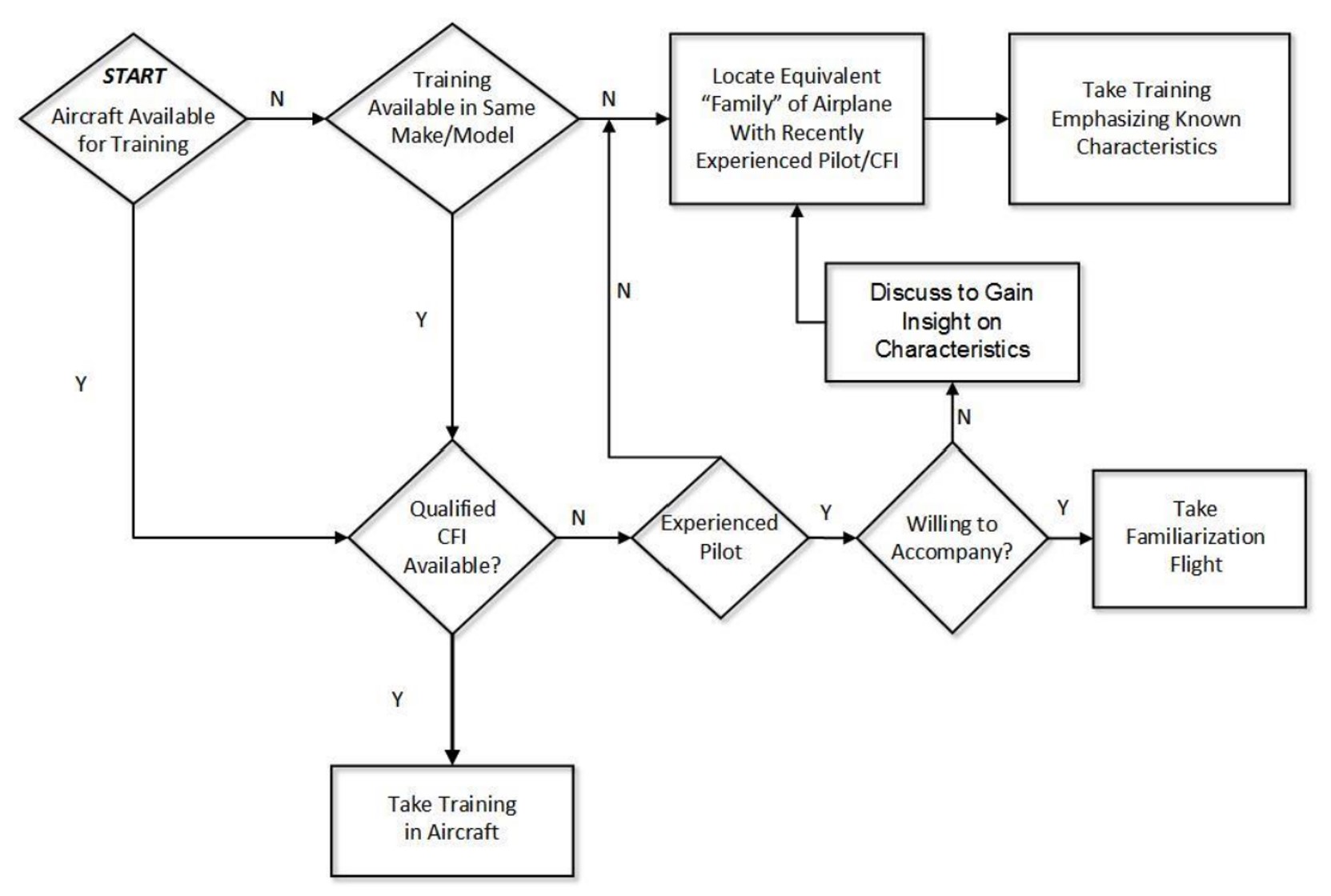

The AC recognises the importance of providing guidance to pilots transitioning between aircraft types, or to experimental aircraft with differing design features to high performance and complex aircraft. It recommends that pilots should develop a training strategy (Figure 7) for mitigating the risks of operation of an unfamiliar aircraft type.

The FAA AC recommends that:

Figure 7: FAA recommended airplane transition training approach

Source: FAA AC90-109A

The guidance recommends firstly that pilots should consider undertaking flight training with a qualified flying instructor in the proposed transition aircraft, the same make and model or an aircraft that exhibits the same design features or characteristics of the transition type. If instruction is unavailable, seek another experienced pilot to conduct a familiarisation flight. However, if the instructor is unwilling, at least discuss the differences and expected characteristics of the transition aircraft.

The guidance further recommended that pilots take a risk management approach to formally identify the hazards and mitigate any known or elevated risks identified.

US registration

It was reported that, to avoid operating under Australian aircraft requirements, the owners decided to leave the aircraft on the US register, and apply on behalf of the registered owner to CASA for a special flight authorisation[8] (SFA) for operations in Australia.

In order for this to occur, the FAA required the registered owner of N600 to have US citizenship. The owners of N600 approached a mutual friend with dual Australian/US citizenship, to act in an administrative role as the registered owner. The owners then applied on behalf of the registered owner to CASA for a SFA in order to operate N600 in Australia.

CASA Special flight authorisation

On 19 October 2022, CASA instrument CASA SA 22/2982 was issued providing a SFA for N600 to operate in Australia under conditions that included that the aircraft be maintained in accordance with the requirements of the FAA. Other operational requirements included that it only be flown in day VFR, must not be operated over populous areas, operated in accordance with CASR Part 91, and only be flown by nominated persons of the registered owner.

Witnesses

A witness at Temora saw N600 at the fuel bowser after conducting circuits, and spoke generally with the pilots by radio about the aircraft. Nothing unusual about the aircraft was observed by the witness prior to its departure from Temora.

The last witness to see the aircraft was at Wedderburn, shortly before the accident, and recalled N600 conducting a go-round after landing and recounted that the aircraft did not climb as expected.

A witness near the accident site just prior to impact recalled the noise of the aircraft reverberating off a nearby water storage tank seconds before impact and described it as ‘revving high and sounded like a machine gun firing’.

Survival aspects

Examination of the aircraft wreckage indicated that the initial impact was in a controlled state at a slow speed, into dense trees. The cabin structure surrounding the cockpit was significantly disrupted during the later stages of the accident sequence, and was not considered survivable.

The carriage of an appropriate emergency locator transmitter (ELT) and/or personal locator beacon (PLB) was a requirement under Civil Aviation Regulation (CAR) 252A unless, among other requirements, the aircraft would be operating within a 50 NM radius from the original point of departure. The ELT fitted to N600 was not compliant with Australian requirements. No crash activation of the ELT was detected or advised by authorities after the accident. A family member identified that one of the pilots was carrying a PLB onboard the aircraft on the day of the accident. However, given the post impact fire and severe degradation of the site, the ATSB was unable to locate the PLB.

Although not legally required, the pilots had not lodged a flight plan or arranged a SARTIME to be held by a responsible person. One of the pilot’s spouses was awaiting the arrival of the aircraft at Wedderburn but was not in receipt of a flight plan or nominated SARTIME.

Safety analysis

On 26 December 2022, a Stoddard Hamilton Aircraft, Glasair Super II FT, registered N600, departed Bankstown, New South Wales for a private flight to Temora, and then onto Wedderburn. N600 conducted a landing and go-around on runway 17 at Wedderburn. However, during the go‑around, N600 failed to achieve sufficient climb performance and impacted terrain about 2.7 km to the south-west of Wedderburn aircraft landing area. The aircraft was destroyed, and the two pilots on board were fatally injured.

This analysis will explore airworthiness considerations pertaining to N600, relating to the engine, reduction gearbox and propeller, the pilots’ experience on the aircraft type, control layout, the approach to land at Wedderburn and general conditions for operation in Australia.

Climb performance

After conducting a landing and go-around from runway 17 at Wedderburn, N600 encountered reduced climb performance and was unable to sufficiently out climb surrounding terrain for about 2 minutes before contacting trees.

Post-accident review of the aircraft engine could not determine any mechanical discontinuity of the engine or gearbox, however due to fire affected components of the electrical and ignition systems, there was not enough evidence to examine these systems definitively.

CCTV footage indicated a fast but controlled landing at Wedderburn prior to the go‑around.

Witness accounts of high engine power leading up to the impact and the degree of post-impact fire indicates sufficient fuel onboard and no evidence of engine stoppage in flight.

Propeller fragments found at the accident site indicated that the propeller had significant rotational speed at initial impact with trees. Propeller pitch settings at the time of the accident were likely in a setting to facilitate take-off power, however the pitch setting at the time of the go-around could not be determined.

Witness indications of a ‘machine gun noise’ may indicate propeller noise, imbalance or damage prior to the impact, however, as post-impact evidence was mostly consumed by fire these possibilities were unable to be further examined.

Therefore, with the limitations of evidence, the ATSB could not determine the reasons why the aircraft was unable to sufficiently out climb surrounding terrain.

Pilot experience on amateur-built aircraft

Both pilots had significant experience in larger multi-engine aircraft and neither had flown N600 prior to the day of the accident. While experienced in larger conventional aircraft operations, there was little evidence to support recent flying experience in light, single-engine, or amateur-built aircraft types.

Each amateur-built aircraft by their very nature is unique. The aircraft builder develops their own systems architecture to accommodate their selected components. This may vary significantly to conventional aircraft configurations and systems.

The absence of previous experience on the aircraft type and recent single-engine flying likely did not prepare the pilots for the challenges of managing an emergency on take-off of a single-engine, experimental amateur-built aircraft with particular design, performance, and control differences.

Special flight permit

The owners of N600 operated the aircraft from Bankstown Airport and over populous areas on the morning of the accident. This was not in accordance with condition 6 as detailed in schedule 2 of the special flight authorisation approved and issued by CASA.

Flight over populous areas in aircraft with a non-certified automotive engine, increases the risk of injury and death to third parties not associated with the operation of the aircraft and reduces the emergency landing options available to pilots if an emergency occurs during take-off.

Non-conventional systems in amateur-built aircraft

Amateur-built aircraft traditionally have different attributes to that of certified aircraft. This can sometimes be evident in the control system layouts and actuation. In the case of N600, the propeller pitch rocker switches were reversed in activation orientation from the left to the right seat. Even with prior knowledge of this control layout, it is likely that operating the aircraft from a different seating position would increase the likelihood of inadvertent pitch change reversal in an emergency during a critical phase of flight, although it could not be determined which seat the aircraft was being operated from at the time of the accident.

The absence of a propeller pitch position indicator or visual references to the pitch settings increases pilot reliance on pre-set throttle and pitch settings prior to take-off, which may not be adequately set during a go-around.

Circuit approach and go-around at Wedderburn

The final approach to land at Wedderburn was conducted after a wide circuit on runway 17 without an overhead circuit join, limiting the appreciation of the wind direction on the ground. This likely led to landing with a quartering left-tailwind in hot and gusty conditions, increasing the aircraft’s ground speed for landing. It is likely that this higher ground speed, downwind landing was a significant factor in pilot decision making to conduct a go‑around.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the collision with terrain involving Stoddard Hamilton Aircraft Glasair Super II FT, N600 near Wedderburn, New South Wales on 26 December 2022.

Contributing factors

- For reasons that cannot be determined, N600 did not achieve sufficient climb performance after take-off from Wedderburn, which led to a collision with terrain.

- The pilots were not experienced in the characteristics of N600's systems, performance and handling, which limited their ability to effectively manage an in-flight emergency.

Other factors that increased risk

- The pilots operated N600 over a built-up area after departing from Bankstown. The special flight permit did not permit operations of experimental aircraft with automotive conversion engines in these areas due to increased risk to third parties and people on the ground.

- N600 was likely fitted with reversed in activation orientation propeller pitch change rocker switches on the left and right side of the throttle. This increased the risk that a pilot flying from the right seat would operate the propeller pitch change opposite to the desirable selection.

Other findings

- The pilot of N600 conducted a downwind landing on runway 17 which likely prompted the pilot to conduct a go-around.

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- Bureau of Meteorology

- OzRunways

- FlightRadar24

- ADS-B Exchange

- Federal Aviation Administration

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- New South Wales Police Service

- Glasair aircraft

- maintenance organisation for N600

- FAA A&P maintainer

- Airservices Australia

- accident witnesses

- CCTV footage

References

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- Federal Aviation Administration

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Airservices Australia

- Bureau of Meterology

No submissions were received from the directly involved parties for changes to the report.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2023

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] Visual flight rules: a set of regulations that permit a pilot to operate an aircraft only in weather conditions generally clear enough to allow the pilot to see where the aircraft is going.

[2] A rectangular take-off and landing pattern comprising of upwind, crosswind, downwind, base and final approach legs.

[3] Runway number: the number represents the magnetic heading of the runway.

[4] To abandon landing and make a fresh approach.

[5] Aircraft supplied in kit form and is designed to be constructed for the education and recreation of the owner.

[6] Wind coming from behind the aircraft direction, either the left or right side of the aircraft.

[7] Informed participation relies on the premise that before you take part or pay for an activity that you are fully aware of the potential risks and consequences.

[8] A legislative instrument allowing operation of a foreign registered amateur-built aircraft in Australia subject to certain conditions.