Executive summary

What happened

On 30 November 2022, a Boeing 737, registered VH‑YFH and operated by Virgin Australia, commenced its take-off roll from the A3 intersection of Brisbane Airport’s runway 19L. During the take‑off the aircraft briefly entered, and became airborne in, the section of the runway that was closed due to the runway works. The aircraft completed the departure and continued onto its destination where a maintenance inspection subsequently cleared the aircraft of any damage.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that the briefing package for the aircraft’s previous sector from Melbourne to Brisbane included:

- a dispatcher’s note which stated that Brisbane RWY 01R had a displaced threshold, but without any resultant landing weight performance limitation

- a notice to airmen (NOTAM) with the headline RWY 01R THR DISPLACED, which identified reduced runway distances for take-off and landing on Brisbane’s runways (RWY) 01R/19L

- critical performance data appended to the displaced threshold NOTAM.

The captain misinterpreted the dispatcher’s note to mean that there were no performance requirements for operations on RWY 19L. The captain reviewed the NOTAMs and, based on this misunderstanding, dismissed the NOTAM as not being relevant for their operation. There was uncertainty about whether the first officer reviewed the dispatcher’s note and NOTAMs in Melbourne, but if they were, the relevance of the note and this NOTAM was probably missed. As such, neither crew member identified the critical performance data appended to this NOTAM.

The NOTAMs were not reviewed en route or as part of the approach briefing prior to descent into Brisbane, as required by the operations manual. Additionally, the automatic terminal information service (ATIS) advice of the reduced landing distance for RWY 19L was not identified and accounted for in the performance calculations for the landing (or subsequent departure) on that runway. Fortunately, this did not affect the landing as the landing’s stopping solution was based on the aircraft exiting the runway well before the closed section. The flight crew’s misunderstanding was reinforced by the absence of any visible runway works or other indications of restrictions on the runway during the landing.

Due to the now‑established belief that there were no performance requirements for operations on RWY 19L, together with time pressures and distractions from prioritising training needs, the flight crew used the full runway length in the performance data calculation for departure, instead of the reduced length identified in the ATIS and NOTAM. This resulted in a departure with insufficient runway available due to the aircraft being overweight for that reduced runway length.

Finally, contrary to the requirements of Part 139 Manual of Standards, the A3/19L intersection departure point take-off run available Movement Area Guidance Sign presented a take-off distance that was more than that available, creating the potential to mislead flight crews about the status of the runway when conducting a departure from that point.

What has been done as a result

Virgin Australia implemented a number of safety management, procedural and information‑based changes designed to improve flight crew awareness of changes to runway configuration and related aircraft performance criteria.

Brisbane Airport Corporation implemented several safety actions to reduce the risk associated with this type of occurrence. These included:

- changes to departure and arrival procedures associated with runway works

- redrafting of the NOTAM to clarify the operational changes to both runways 01R and 19L, and the procedures to ensure correct runway distance was displayed on movement area guidance signs

- publication of an aeronautical information circular supplement for the works.

Safety message

Flight crews must ensure they consider possible variations to take-off and/or landing dimensions when determining runway performance data. While this operator’s procedures accounted for such changes through notification of performance requirements within their NOTAM system, due to a combination of distraction and incorrect assumption, they were not identified.

When presented with many NOTAMs, flight crews need to be aware that dismissing them based on the headline alone increases the risk that safety relevant data may be overlooked. As an additional defence, flight crews should ensure that the data input into that calculation is in conformance with other relevant information, such as the ATIS.

The occurrence

Overview

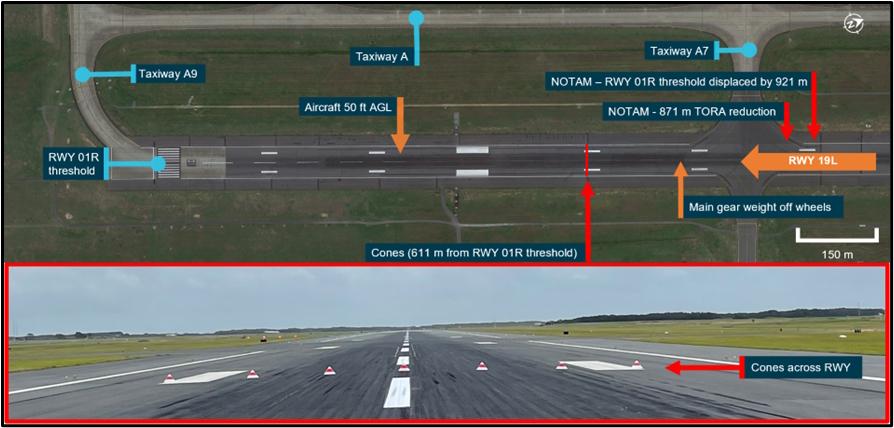

On 30 November 2022 a Boeing 737-8FE (B737), registered VH‑YFH and operated by Virgin Australia as flight number VA324, commenced its take-off roll from the A3 intersection of Brisbane Airport’s runway 19L. The take-off thrust and speeds set by the flight crew for the take‑off from A3 were based on the full runway length from that intersection being available. However, unrecognised by the crew, the take-off distance available for runway 19L had been reduced at the upwind (01R threshold) end by 871 m due to runway works. As a result, the thrust set for the take‑off was insufficient for the actual runway length available and the aircraft briefly entered, and became airborne in, the section of the runway that was closed due to the runway works. The aircraft completed the departure and continued on to its destination where a maintenance inspection subsequently cleared the aircraft of any damage.

The sequence of events that resulted in the runway excursion commenced earlier the same day, during flight planning for the previous sector from Melbourne to Brisbane.

Melbourne

Arrival

VH-YFH arrived in Melbourne as flight number VA254 from Canberra at 0846 EDT,[1] about 10 minutes behind schedule. The aircraft was scheduled to depart Melbourne for Brisbane as flight number VA319 at 0910 EDT. The flight crew consisted of a training captain (captain) and a first officer (FO). The captain had been assigned a number of ‘line flying under supervision’[2] sectors with the FO over the previous 2 days as part of the FO’s conversion onto the B737.

Pre‑flight

Flight planning package

Shortly after arriving, the flight crew received the flight planning package[3] (see the section titled Flight planning) for the flight from Melbourne to Brisbane. This package included the operational flight plan (OFP),[4] NOTAMs[5] for the sector and flight operations engineering (FOE) data appended to the relevant NOTAMs. The captain recalled that the package was initially missing a part of the NOTAMs section, although a full reprint was subsequently received prior to departure.

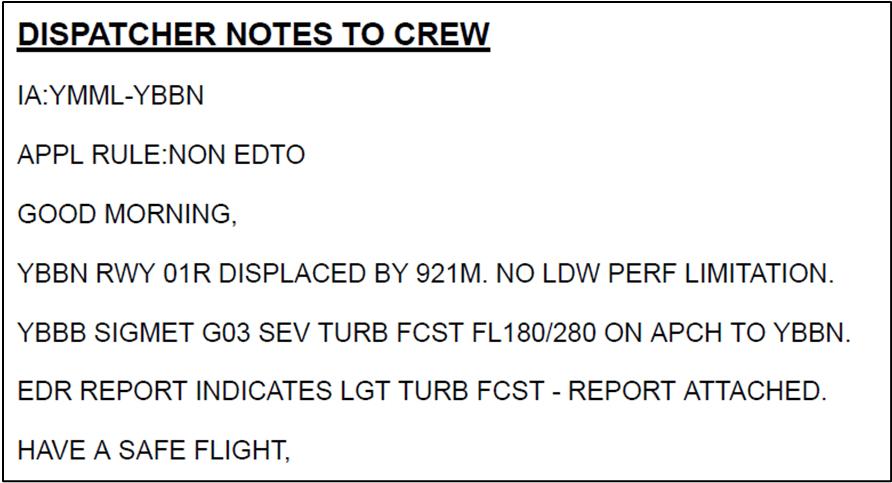

The OFP commenced with a section titled ‘Dispatcher Notes to Crew’ (Figure 1), which included a note from the dispatcher that stated:

YBBN RWY 01R DISPLACED BY 921M. NO LDW PERF LIMITATION.

The flight crew expected the approach and landing into Brisbane would be on runway (RWY) 19L. The captain incorrectly interpreted the dispatcher’s note to mean that the displaced threshold of RWY 01R did not have associated performance requirements for runway 19L (see the section titled Flight dispatch). The captain then reviewed the Brisbane NOTAMs, which included a NOTAM (NOTAM YBBNC1174/22) with the headline ‘RWY 01R THR DISPLACED’. This NOTAM was dismissed as it referred to the displaced runway threshold in the dispatcher note, and because the headline did not include any reference to RWY 19L (which was the expected landing runway).

Figure 1: Dispatcher notes for VA319 (Melbourne to Brisbane)

Source: Virgin Australia

FOE requirements for RWY 19L

The NOTAM section of the flight planning package also included a company notice, titled ‘VOZ FOE COMPANY REMARK’, appended to the displaced threshold NOTAM YBBNC1174/22 (see the section titled VA319 (Melbourne to Brisbane) flight planning package). This notice included specific data required to be used for both landing and take‑off performance data calculations when using Brisbane RWY 01R and RWY 19L. The captain did not identify the company notice associated with NOTAM YBBNC1174/22. There was uncertainty about whether the FO read the dispatcher notes and NOTAMs prior to departure from Melbourne, but if they did, the relevance of the dispatcher’s displaced threshold note and NOTAM was probably missed. As a result, both flight crew were unaware of the performance data calculation requirements for operations at Brisbane’s RWY 01R and RWY 19L.

En route to Brisbane

The aircraft departed Melbourne at 0940 EDT with the flight to Brisbane expected to take about 2 hours. The FO conducted the pilot flying (PF)[6] duties for the sector, while the captain was the pilot monitoring (PM). The intention was to reverse these roles for the later return flight to Melbourne. Available spare time during the cruise portion of the flight was used to cover training‑related matters.

As the aircraft approached Brisbane, the crew completed arrival preparations, which included recording the Brisbane automatic terminal information service (ATIS),[7] calculating the landing performance data, and briefing for the approach and landing. The ATIS stated that arrivals were being conducted onto RWY 19L and RWY 19R, and that RWY 19L had a reduced length with the landing distance available being 2,689 m.[8]

The flight crew did not review the Brisbane NOTAMs inflight or as part of arrival preparations.

While the crew completed the landing performance data calculations based on the full length of RWY 19L being available, and not the reduced length as stated on the ATIS, the stopping solution (see the section titled Enroute landing performance calculator) was based on the aircraft exiting the runway at the A6 taxiway.

Brisbane

Arrival

VH-YFH landed on Brisbane’s RWY 19L at 1050 EST[9] and exited the runway using the A6 rapid exit taxiway located about 850 m from the displaced threshold at the end of RWY 19L.[10] The flight crew stated that they did not observe any runway works activity or markers indicating works on the runway during the landing roll and exit from the runway.

Post-flight

VH-YFH was scheduled to arrive at the gate in Brisbane at 1020 and depart for Melbourne as VA324 at 1055. The aircraft arrived at the gate 34 minutes behind schedule, at 1054.

Following completion of post-flight duties, the flight crew did not immediately commence preparation for VA324. The captain’s observations of the FO’s performance as PF for the landing into Brisbane identified a need to alter the intended flight crew duties for the VA324 sector and assign the FO the PF role once again. To support this decision, the captain allocated time to debrief the FO on their performance during the completed sector and to provide training support for the return flight. During those training discussions the crew received the flight planning package for the return flight to Melbourne.

Pre-flight

The training discussions were put on hold while the flight crew reviewed the OFP and dispatcher notes and determined the fuel order for the VA324 sector. The OFP included a dispatcher’s note that stated:

YBBN RWY 01R THR DISPLACED 29/2100-30/0630Z

The flight crew understood that this note was in reference to the same runway matter identified by the dispatcher in the previous sector’s OFP and was dismissed.

The captain then finalised the training discussion and, at its completion, the FO exited the flight deck to conduct an exterior inspection of the aircraft while the captain commenced pre‑flight duties. The captain later estimated that around 5 minutes of the turnaround was spent in the training discussion.

As part of the pre‑flight duties, the captain obtained a hard copy of the ATIS from the ACARS,[11] and used that data to fill out the relevant fields of the take-off data card (TODC). The captain made a handwritten entry ‘2689 TORA’ in the remarks section at the bottom of the card (see the section titled Pre‑flight procedures and the performance data calculation). The take-off performance data was then determined using the onboard performance tool (OPT).[12] The captain decided to use the taxiway A3 intersection with RWY 19L as the take-off commencement point (Figure 2). The power setting, take-off speeds and other data relevant to this take-off commencement point were then calculated using the OPT’s runway selection that related to the normal runway length from A3 rather than the reduced available length. The resultant calculated data was then transcribed onto the TODC.

Figure 2: VA324 departure

A Google Earth image of Brisbane Airport with the departure track of VA324 overlaid. The image shows location and timestamps for specific points of the departure.

Source: Google Earth, modified by ATSB

After completing the exterior inspection, the FO returned to the flight deck and commenced their pre‑flight checks. This included a required independent calculation of the take-off performance data using the OPT. The FO conducted the calculation using data from the TODC (previously filled out by the captain). The FO stated that they did not see the captain’s annotation of ‘2689 TORA’ in the remarks section.

On completion of the performance calculation, both flight crew cross-checked and confirmed agreement on the calculated data using the OPT cross-check function. The subsequent pre‑flight procedures and checklists then confirmed that the data entered into the flight management computer was in agreement with that on the TODC. The FO then conducted a departure briefing, which included stating that the take-off was planned to commence from the A3 intersection for RWY 19L. The aircraft was then prepared for push back from the gate.

It is likely that the NOTAMs were not reviewed by either pilot during the turnaround and that while the specific reasons could not be determined, it may have been due to a combination of distraction, time pressure and a previously‑formed view of the NOTAM content.

Departure

The flight crew commenced push-back at 1139 and, at 1143, requested a taxi clearance from air traffic control (ATC), advising that ATIS information D had been copied, and that an A3 departure could be accepted. ATC cleared the aircraft to taxi to the A3 runway holding point. As the aircraft approached the holding point, ATC cleared the aircraft for take-off from RWY 19L. On passing the runway distance signs (see the section titled Movement area guidance signs) at the A3 holding point at about 1147, the flight crew completed the take-off performance check (see the section titled Runway entry performance check) and, with all checks completed, the aircraft entered the runway. Both flight crew later recalled that the runway looked clear with no markers or obstructions visible from their take-off commencement point.

The crew performed a rolling take-off, with take-off power being applied at 1148. The captain later recalled that, following the power application, their attention was mostly inside the aircraft performing PM duties and that they did not observe any obstructions or cones on the runway during the take-off.

The FO recalled that:

- at an airspeed of about 100 kt, they observed cones positioned in a line across the runway

- while they considered the cones an immediate threat, they estimated that the aircraft would become airborne before the cones and, as the aircraft’s airspeed had exceeded 80 kt, they continued the take-off

- they did not verbally notify the captain of sighting the cones as it was assessed that the aircraft would clear them

- they commenced the take-off rotation before the cones and as the aircraft climbed through about 50 to 70 ft above the runway, the cones were observed to pass underneath.

Recorded audio[13] from the ATC tower identified that, during the aircraft’s take-off run, when it was about midway between the runway intersections of taxiways A6 and A7, the tower controller commented on whether the aircraft was going to rotate. As the aircraft passed over the cones, the tower controller remarked that the aircraft had passed very close over the cones. ATC immediately called a ground vehicle on the tower frequency to inspect the cones. The aircraft’s flight crew heard this exchange before transferring to the departure frequency. Shortly after, the ground vehicle reported that, while the cones did not appear to have been struck, 3 cones had been blown from their original position.

About midway through the climb out of Brisbane, ATC informed the flight crew of the cones being blown over during their departure. The flight crew discussed the departure, noted that the aircraft was handling normally and continued to monitor the aircraft’s instruments for abnormal indications. Shortly after, the captain contacted Virgin maintenance to report that they may have struck cones during departure and organised an inspection on arrival. The aircraft proceeded on to Melbourne without further incident and landed safely at 1441 EDT. The aircraft was subsequently cleared of any damage by a maintenance inspection in Melbourne.

Context

Pilot information

Both the captain and the first officer held Air Transport Pilot Licences (Aeroplane) with Class 1 aviation medical certificates and were appropriately qualified for the flight. The ATSB found no indicators that increased the risk of the flight crew experiencing a level of fatigue known to affect performance.

The captain had accumulated about 9,000 hours of flight experience, of which about 5,500 hours were on the Boeing 737 (B737). In the previous 90 days, the captain had flown 73 hours on B737 type aircraft. The first officer had accumulated about 13,000 hours of flight experience, of which about 9,200 hours were on the B737, with 77 hours flown in the previous 90 days.

Flight planning

Flight plan manager

Flight crews were provided with all required pre‑flight briefing material in a single document – the flight planning package (FPP). The FPP was generated by flight dispatch using the Flight Plan Manager (FPM), a flight planning software package used by Virgin Australia to automate the collation of flight planning data and the production of briefing material for flight crews. The FPP comprised the operational flight plan (OFP),[14] weather data, route plots and NOTAMs for the sector.

NOTAMs were automatically received and imported into the FPM database. For a particular FPP, the FPM software would filter the NOTAMs, presenting only those relevant to that sector, format that NOTAM data into a form usable in a pre-flight information bulletin (see the section titled Notice to Airmen), and attach any company remarks applicable to that NOTAM.

Flight dispatch

Virgin flight dispatch was responsible for the maintenance of the FPM database and the production of the FPP, including the acquisition, collation and evaluation of NOTAM, meteorological and other operational information in support of flight planning activities. Flight dispatch was also responsible for the distribution of NOTAM data to relevant specialist functions within Virgin, such as flight operations engineering (FOE).

As part of the flight planning process, flight dispatchers were required to establish whether the runway, environmental and aircraft performance conditions required a reduction in the normal aircraft limit weights—that is, whether there was any performance limitation to the aircraft’s weight, such as for take-off and/or landing. This was done through calculations using the onboard performance tool (OPT) (see the section titled Performance calculators).

In determining whether there was a limiting weight to be applied, dispatch used weather conditions sourced from TAF[15] data, and were required to ensure consistency of that weather data with other data sources such as METAR[16] and automatic terminal information service (ATIS). Flight dispatch was also required to apply any FOE-determined performance requirement in the limiting weight calculation. When the calculation determined that a weight restriction was to be applied, that limiting weight (or performance limitation) was to be input into the FPM and applied to the overall plan. Any performance limitation was to be noted in the FPP, and the parameters used for the calculation provided in the OFP. The dispatcher was also required to ensure that flight crew were aware of the performance restriction.

Flight operations engineering

On receipt of a NOTAM from flight dispatch, FOE were required to determine whether the NOTAM had a performance impact on operations. For NOTAMs impacting performance, FOE would input the required performance response into the FPM as a company remark, as well as amend the OPT database with the relevant input options applicable to that NOTAM. Where FOE determined that there was no performance impact associated with a received NOTAM, an FOE company remark with a statement such as ‘NO PERFORMANCE IMPACT’ would be input into the FPM.

The flight planning package

Operational flight plan

The FPP’s operational flight plan (OFP) component contained a synopsis of data critical to the conduct of the planned flight. It included information such as the dispatch message, fuel and weight data,[17] the navigation log[18] and any applicable performance restrictions.[19] The dispatch message comprised dispatcher notes to the crew, aircraft discrepancy items and the filed air traffic services[20] flight plan.

Dispatcher notes were required for every flight, and were used by dispatchers to notify flight crew of all decisions pertaining to the preparation of the briefing package and any other information that could assist in the safe conduct of the flight. The notes could also be used to provide flight crew with an overview of the flight planning requirements or any special considerations.

NOTAMs

The FPP was the primary source of NOTAM information for flight crews, and the only source of information for FOE performance requirements. NOTAMs provided as part of the FPP by flight dispatch were stated to be the latest available for departure and arrival ports and, as a general rule, were valid for 30 minutes prior to the estimated time of departure and for 4 hours after the estimated time of arrival.

The National Aeronautical Information Processing System (NAIPS)[21] was an alternative source of NOTAM information available to flight crew and was accessible through the flight crew’s electronic flight bag (EFB).[22] Unlike the FPP NOTAM data, NAIPS NOTAMs were unfiltered and did not have FOE company remarks data attached.

VA319 (Melbourne to Brisbane) flight planning package

The VA319 flight dispatcher determined that there was no landing weight performance limitation for the Melbourne to Brisbane sector resultant from the displaced threshold for Brisbane’s RWY 01R. This was notified to the flight crew through a remark in the ‘Dispatcher notes to crew’ section of the FPP (see Figure 1) as follows:

YBBN RWY 01R DISPLACED BY 921M. NO LDW PERF LIMITATION

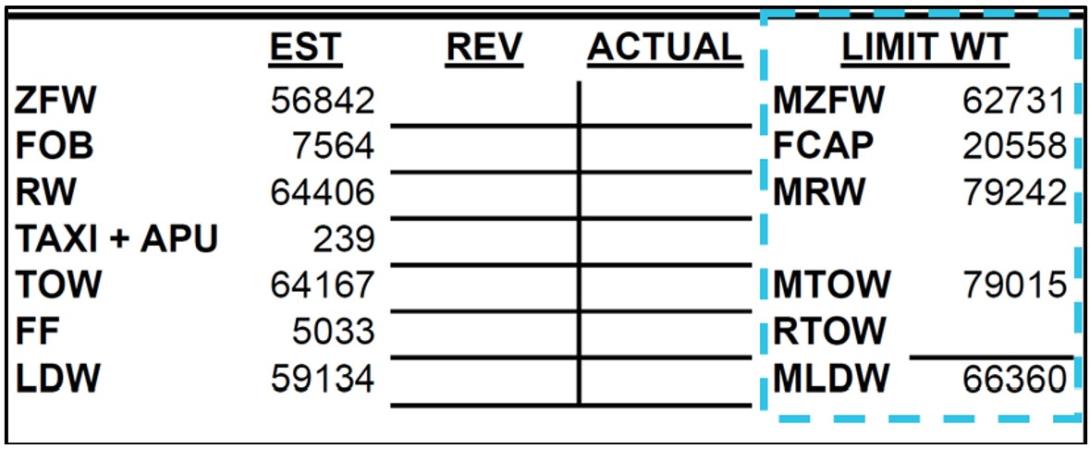

The absence of any performance weight limitation was also identifiable from the aircraft limit weights section of the OFP (Figure 3), where the limit weights listed were maximum weights for those conditions in the aircraft’s flight manual. While the dispatcher’s note identified that there were no performance weight limitations, the OFP did not present the specific parameters used in the limit weight calculations (see the section titled Flight dispatch). However, flight crew could ascertain the parameters from various parts of the FPP.

Figure 3: VA319 limit weights

An image of the limit weight section of VA319 OFP.

Source: Virgin Australia, annotated by ATSB

VA319 NOTAMs

The VA319 FPP consisted of 33 pages, of which 18 contained the sector’s NOTAMs. There were about 120 individual NOTAMs within the package.

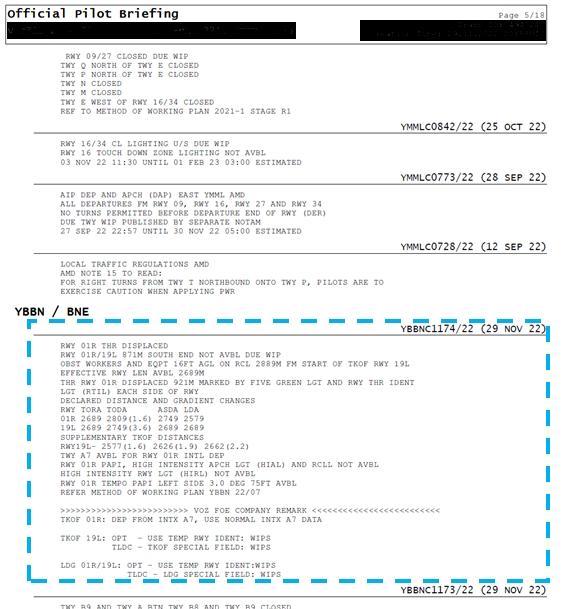

The first of the Brisbane NOTAMs listed was NOTAM YBBNC1174/22 with the headline ‘RWY 01R THR DISPLACED’ (Figure 4 – broken blue box highlighting added by the ATSB). This NOTAM appeared on page 5 of the NOTAMs section and detailed the reduction in length for runways 01R (RWY 01R) and 19L (RWY 19L) due to aerodrome works being conducted around the RWY 01R threshold. Appended to the end of this NOTAM was a company remark titled ‘…>>> VOZ FOE COMPANY REMARK <<<…’. This remark was to notify the flight crew of FOE-required modifications to the take-off and landing performance data calculations for Brisbane RWY 01R and RWY 19L as a consequence of NOTAM YBBNC1174/22.

Figure 4: Page 5 of the NOTAM package, highlighting NOTAM YBBNC1174/22 and its associated FOE performance requirement

An image of page 5 of the VA319 NOTAMs, with YBBN NOTAM 1174/22 highlighted.

Source: Virgin Australia, annotated by ATSB

VA324 (Brisbane to Melbourne) flight planning package

Similar to VA319, the VA324 flight dispatcher determined that there were no performance weight limitations for the return sector to Melbourne as a result of the displaced threshold, and while the OFP did not include a direct statement of the parameters used in that determination, those parameters could be ascertained from data within the FPP.

The VA324 flight dispatcher stated that one of the roles of the Dispatcher Notes was to highlight to flight crew any information considered critical by the dispatcher, such as NOTAM YBBNC1174/22. Further, given the short turnarounds often associated with multi-sector flights, the dispatcher intended to direct the flight crew’s attention to this NOTAM through inclusion of the following statement in the dispatcher notes:

YBBN RWY 01R THR DISPLACED 29/2100-30/0630Z.

VA324 NOTAMs

The VA324 FPP consisted of 30 pages, 13 of which contained the sector’s NOTAMs. There were about 80 individual NOTAMs within the package.

The YBBNC1174/22 NOTAM was the first of the NOTAMs included within the VA324 NOTAM package and included an attached FOE company remark. The presentation of the NOTAM and its FOE remark directly reflected the VA319 presentation (Figure 4), but was split over 2 pages, with the FOE remarks appearing on the second page.

FOE conspicuity

The operator’s internal investigation into the event noted that performance critical NOTAMs with associated FOE data were presented in the FPP in the same typeface as less critical NOTAMs, and that there was ‘little to draw the reader’s attention’ to something that was critical to safety of flight. The investigation noted that, in a high workload environment with many distractions, it was ‘…not difficult to miss text that looks the same’.

The VA319 FPP contained 8 NOTAMs with FOE remarks attached, while the VA324 FPP contained 5 NOTAMs with FOE remarks attached. For both FPPs, only 2 of the FOE notices contained performance requirements, while the rest were notifications that the NOTAM had no performance effect. The ATSB also noted that FOE remarks were highlighted via a unique banner (Figure 4) intended to increase their conspicuity to flight crew.

Notice to Airmen

Notification of aerodrome facilities

Airport operators were required to report detailed information about their various aerodrome facilities to Airservices. This information was then published in the Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP). Short-term changes to these facilities were also required to be notified to Airservices. Users of those facilities were then advised of these short-term changes through the NOTAM system.

NOTAM standards

CASR Part 175 prescribed standards covering when NOTAMs were to be issued and how they were to be structured and formatted. A detailed examination of those standards, and the documents in which they are found, is at Appendix – NOTAM standards and related guidance materials.

A NOTAM issued by Airservices was required to meet a prescribed format and contain specific information about the matter being reported. That format comprised multiple fields that not only provided a description of the matter(s) being reported—referred to as the free text section—but also contained coding that enabled both the automatic classification and filtering of that NOTAM, The NOTAM content presented to the flight crew in the FPP was limited to the free text section.

As well as meeting the format and content requirements, a NOTAM was also to adhere to various rules. These are covered in detail at Appendix – NOTAM standards and related guidance materials, but can be summarised under the following 4 basic principles:

- A NOTAM shall deal with only one subject and one condition of that subject. It shall be as brief as possible and compiled such that the meaning is clear, and without the need to refer to another document.

- The subject matter and related condition shall be determined in accordance with specific coding procedures and tables found in the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Document 8400.[23]

- The code identifying the subject or denoting its status of operation is, whenever possible, self‑evident. Where more than one subject could be identified by the same self-evident code, the most important subject is chosen.

- The content of the free-text section of the NOTAM shall be based on the selected code, be clear and concise and if possible limited to 300 characters—to facilitate use in a Pre‑flight Information Bulletin (PIB).[24]

Of the various standards-defining documents identified in CASR Part 175, only ICAO Document 8126[25] included material on circumstances where multiple NOTAMs could be combined and reported in a single NOTAM. The document stated:

The NOTAM Code selected describes the most important status or condition to be promulgated.

Although not included in CASR Part 175 as a standards document, EUROCONTORL[26] guidance material on NOTAMs included the following caution on combining NOTAMs:

The negative impact on end-users caused by NOTAM proliferation is not to be solved by including more information in a single NOTAM, but that this fact further increases the difficulty for end-users. More information in one NOTAM makes the message less readable and essential information more difficult to detect.

Assessment of NOTAM YBBNC1174/22

The ATSB sought advice from both ICAO and the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) regarding NOTAM YBBNC1174/22 and its adherence to the applicable standards. ICAO and CASA acknowledged the guidance with regard to NOTAM content being limited to one subject matter and one condition of that subject matter, but differed in the application of this limitation with respect to related content.

CASA advised that the most important status or condition being reported in this NOTAM was the displaced threshold, and that the matters being reported within the free text section were the result of the changed condition of that subject matter. Further, the additional matters being reported were information necessary for the safe conduct of flight. As an overall assessment, CASA stated that the NOTAM met the standards as required under CASR Part 175. On whether the NOTAM’s headline should have contained reference to ‘RWY 19L’, CASA stated that this could not be the case as there was no displacement of that runway’s threshold.

ICAO stated that, as per PANS-AIM, matters not directly related to the subject matter and related conditions should not be included within the free text section, but that there also needed to be a balance between usability and convenience while adhering to the guidance principles. ICAO nevertheless advised that the free text section of the NOTAM held critical information interspersed with less critical information, and that the critical information should have preceded the less critical information. While ICAO indicated that the NOTAM complied with ICAO guidance principles, the information concerning the runway lighting, and probably the taxiway information, should have been published as separate NOTAMs.

Brisbane Airport

Runway works

The Brisbane NOTAM YBBNC1174/22 was published as notification of scheduled works around the threshold of RWY 01R. Those scheduled works were part of a larger programme of works documented in a Method of Working Plan (MOWP) YBBN 22/07,[27] published by Brisbane Airport Corporation (BAC) in August 2022. The works were to be staged over about a year to minimise disruption to operations at the airport. In accordance with the Civil Aviation Safety Regulations (CASR) Part 139, the MOWP detailed the timing, scope of the works and specific aerodrome facilities that would be affected. The MOWP also identified how the individual work stages affected aircraft operations, and listed any NOTAM to be issued, where required, for each stage.

The works around the threshold of RWY 01R were scheduled to commence on 30 November 2022. After being notified of these works by BAC, on 23 November Airservices issued the predecessor of YBBNC1174/22. As a result of some minor changes, that original NOTAM was modified, and on 30 November YBBNC1174/22 was published by Airservices.

Runway distance information

NOTAM C1174/22 included runway distance data under the title DECLARED DISTANCE AND GRADIENT CHANGES. The information immediately below this line provided runway distance measurements used in the calculation of aircraft runway performance data.

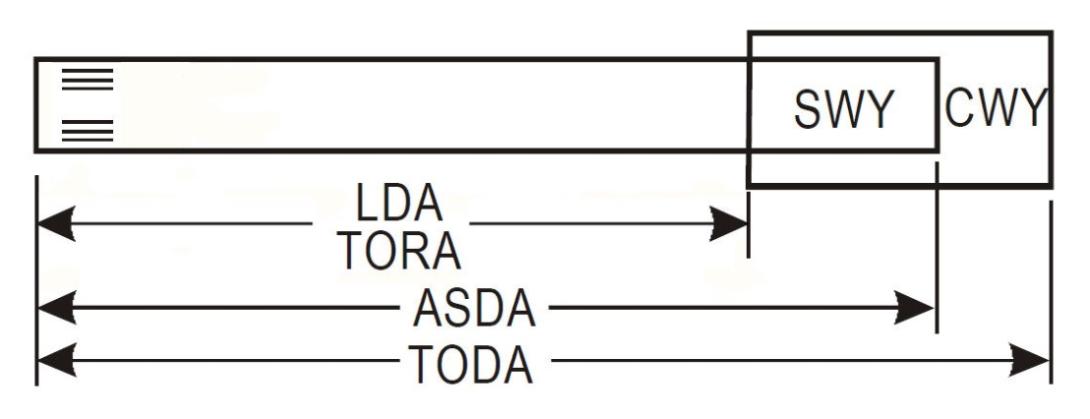

Part 139 Manual of Standards (Part 139 MOS) required aerodrome operators to report various runway distances for publication in the AIP. The following ‘declared distances’, as defined in Part 139 MOS, were to be notified by aerodrome operators (Figure 5):

- Take-off run available (TORA). The length of runway declared available and suitable for the ground run of an aeroplane taking off. The take-off run available may include additional length available from a starter extension if provided, but neither stopway (SWY)[28] nor clearway (CWY)[29] were included in the take-off run available.

- Take-off distance available (TODA). The length of the take-off run available plus the length of the clearway, if provided.

- Accelerate-stop distance available (ASDA). The length of the take-off run available plus the length of the stopway, if provided.

- Landing distance available (LDA). The length of runway which is declared available and suitable for the ground run of an aeroplane landing.

Figure 5: Runway declared distances

A diagram identifying the various components of a runway’s declared distances, and their relationships to the physical dimensions of the runway.

Source: ICAO Annex 14, modified by ATSB

The various take-off and landing distances applicable to RWY 19L[30] and the A3 intersection with RWY 19L, while in unrestricted use and when the displaced threshold was in effect (as notified by NOTAM C1174/22), are stated in Table 1.

Table 1: Runway 19L distances

| Departure designation | TORA | TODA | ASDA | LDA |

| 19L | 3560 | 3620 | 3560 | 3560 |

| 19L/A3 | 2781 | 2841 | 2781 | - |

| 19L-WIPS | 2689 | 2749 | 2689 | 2689 |

| 19L/A3-WIPS | 1910 | 1970 | 1910 | - |

Movement area guidance signs

Movement area guidance signs (MAGS) were installed at the taxiway A3 holding point for entry to RWY 01R/19L. MAGS may be either mandatory instruction signs or information signs. Instruction signs used white lettering on a red background, while information signs used black lettering on yellow background. There were 2 types of MAGS installed abeam that runway holding point (Figure 6):

- a runway designation sign that identified the taxiway and runway, located to the left of the taxiway and adjacent to the holding point

- 2 take-off run available (TORA) signs located either side of the taxiway that stated the TORA distances available in the identified direction from that runway entry point.

The flight crew stated that these signs were not obscured at the time of VA324’s departure. Brisbane Airport personnel advised that the TORA MAGS would not normally be covered or obscured when there was variation in the runway length due to works.

Figure 6: MAGS situated at the A3 holding point for 01R/19L

An image showing the movement area guidance signs at the A3 intersection to runway 01R/19L.

Source: BAC

Part 139 MOS paragraph 8.27(4) stated:

If:

(a) a movement area guidance sign (MAGS) displays declared distance information; and

(b) because of a period of temporary threshold displacement the MAGS information is incorrect for the period;

the MAGS must be obscured until the permanent threshold is reinstated.

The MOWP did not include any instruction for obscuring the TORA MAGS located at the A3 holding point.

OPT calculated runway performance data

Introduction

The Onboard Performance Tool (OPT) was developed by Boeing as the application to be used by flight crew for calculating take-off and landing performance. While the primary source of B737 aircraft performance data was the Airplane Flight Manual (AFM),[31] the OPT provided data equivalent to the AFM and met all take-off and landing regulatory requirements. It was accessed through the Electronic Flight Bag (EFB).

OPT database

The OPT used a database of airports and runways available for use by the operator’s flight crew. That database was maintained by flight operations engineering (FOE). Changes to an airport’s runway data, such as a reduction in runway length notified through NOTAM, required FOE to determine how aircraft performance was affected and what additional runway data was to be included within the OPT database. As part of their response, FOE would amend the database to include a temporary runway identifier with the modified runway data relevant to this change. The requirement to use this temporary identifier would be notified to flight crews through the VOZ FOE COMPANY REMARK notice attached to the relevant NOTAM in the FPP. Updates to the OPT database were automatically sent to the EFB. Prior to the first use of the day, the user was required to ensure that the OPT database version was the latest, as listed within the company NOTAMs. Virgin stated that quality control procedures established within FOE ensured that flight crew were not required to independently verify runway data used by the OPT.

Performance calculators

Introduction

In setting up the OPT for performance calculation, the user was required to select the relevant airframe registration and airport from the database. There were 3 types of performance calculators available:

- take-off performance

- landing performance

- en route landing performance.

Take-off and landing performance calculators

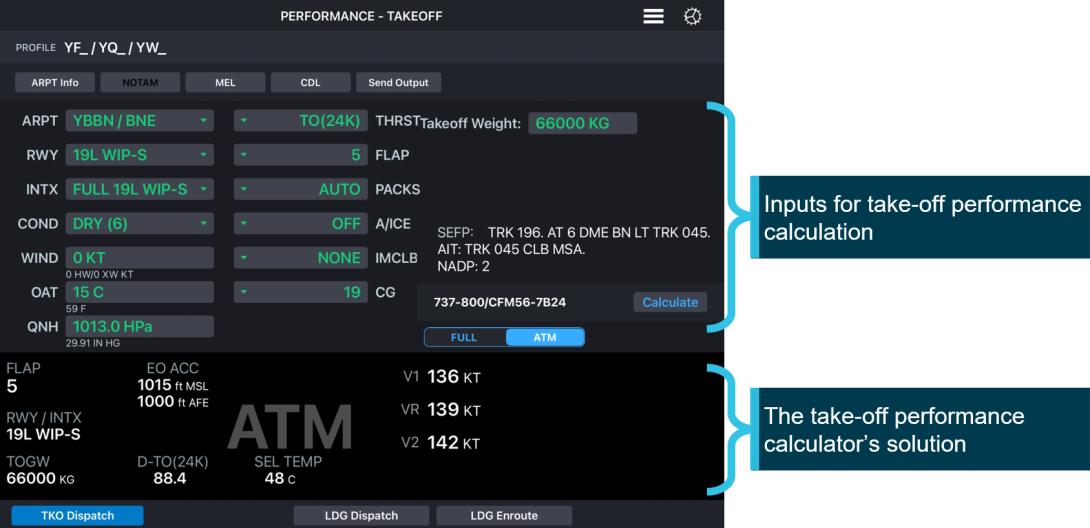

The take-off and landing performance calculators enabled determination of take-off and landing performance data as well as the performance limited weights for take-off and landing. The performance limited weight feature of both the take-off and landing performance calculators were primarily used by flight dispatch during flight planning to determine whether the sector had limiting weight considerations. The take-off performance calculator was used by flight crew for calculating take-off performance data as part of the preliminary pre‑flight procedure (Figure 7).

Figure 7: OPT take-off performance calculation screen

An exemplar image of the OPT take-off performance calculator, with the data inputs in green and, in the lower third, the calculator’s take‑off performance data.

Source: Virgin Australia

When used by flight crew for take-off or landing performance data calculation, the user was required to input data into the various fields, and if a valid performance solution was possible, the application would provide performance data for those parameters. For a take‑off calculation, a valid performance solution would provide data that included the relevant take-off speeds and any available thrust derate.[32] An invalid performance solution would clearly advise the flight crew that a take-off using those parameters was not permitted. With respect to the landing calculator, the performance results included the landing limit weight and relevant landing speed for the selected flap setting at that weight.

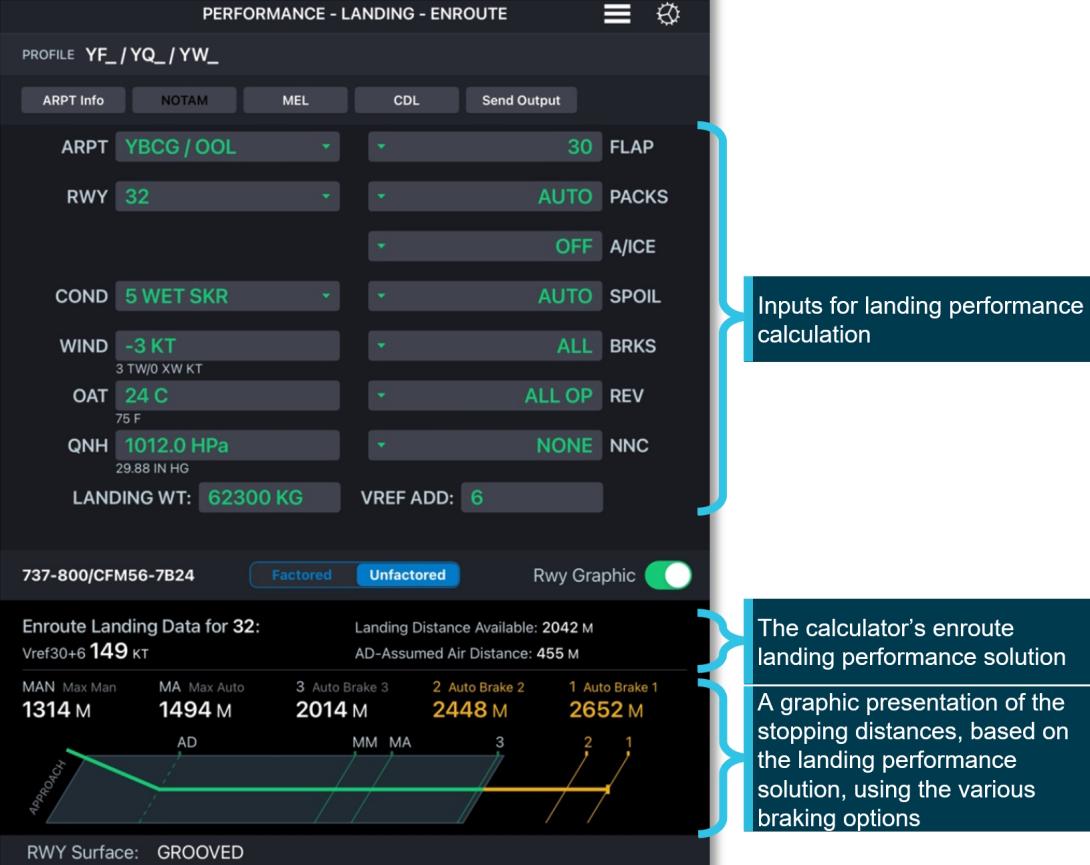

En route landing performance calculator

The en route landing performance calculator was the primary landing data calculator used by flight crew (Figure 8). It provided data based on an input landing weight and selected environmental and aircraft configuration inputs. If a valid landing performance solution was possible, the calculator would provide landing performance data that included the landing speed and stopping distances for the various braking selections available. That stopping data could be displayed in both tabular and graphic form. The selected runway’s landing distance available (LDA) was displayed as a product of the landing data solution.

Figure 8: Exemplar OPT en route landing performance calculator

An image of the OPT en route landing performance calculator, extracted from the Virgin manual. The calculations are for Coolangatta, with the data inputs in green and, in the lower third, the calculated landing performance data. The image also shows the calculated stopping solution in graphic form.

Source: Virgin Australia

Runway distance data

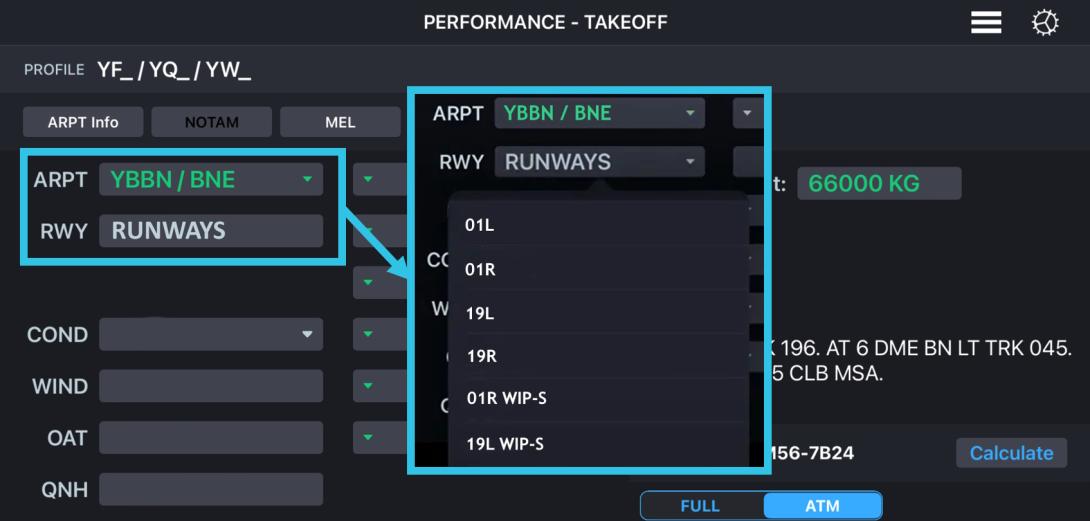

While runway distance data was displayed in the calculation results for the en route landing performance calculator (displayed as the Landing Distance Available), it was not displayed as part of the calculated take-off performance data. However, runway data was available in all OPT calculators through the ARPT Info tab (see Figure 7 and Figure 8). Selecting the ARPT Info tab (Figure 9) provided database details for the airport and runway that were selected as inputs. Intersection details relevant to that runway data was then available through a further selectable option. However, to determine the TORA for an intersection departure, the flight crew needed to manually calculate it using the displayed information.

Figure 9: OPT airport information

An image showing access to runway data through the Airport Info tab in the various OPT calculators.

Source: Virgin Australia modified by ATSB

VA319 landing performance data

For the VA319 landing, the runway (RWY) input for Brisbane Airport (YBBN/BNE) had several selectable options available through a drop-down box. These were, in order, 01L, 01R, 19L, 19R, 01R WIP-S and 19L WIP-S (Figure 10). The 2 WIP-S runway options were the required selections for those runways based on the FOE remark in the VA319 FPP while NOTAM 1174/22 and the RWY 01R threshold displacement was in effect.

As part of their landing performance calculations for arrival into Brisbane, the flight crew selected the 19L option. The calculator provided a stopping solution based on the full runway length, and the other selectable variables input by the flight crew. The displayed landing solution included the LDA for RWY 19L, which was 3,560 m, while the available stopping solutions were based on this full runway length.

While the stopping solution for the landing in Brisbane was based on an incorrect runway length, the landing was not affected by this error. The aircraft was able to exit the runway using the using the A6 rapid exit taxiway, which was about 850 m short of the displaced threshold.

Figure 10: Runway input selection

An image of the OPT take-off performance calculator with the runway options displayed for the VA324 departure.

Source: Virgin Australia modified by ATSB

VA324 take-off performance data

For the VA324 departure, the selectable YBBN/BNE runway inputs were those as stated for the VA319 arrival. However, on selecting the runway, the user was then also able to select various intersection (INTX) departure points available for that runway. While the normal RWY 19L configuration had the FULL and A3 INTX (intersection) options available, FOE had removed the A3 INTX option for RWY 19L WIP-S, and therefore the A3 intersection departure was not an available input.

For the VA324 take-off performance calculation, the flight crew selected the 19L option as the departure runway and A3 as the intersection departure. The OPT provided take-off performance and thrust derate based on the TORA of 2,781 m.

As part of its internal investigation, Virgin calculated the VA324 take-off performance data using the same inputs as the flight crew, but with the 19L WIP-S runway option and an A3 INTX selection (an A3 intersection departure). The OPT displayed an invalid take-off performance solution, with the following message being displayed:

No takeoff allowed. Planned weight exceeds max allowable weight of 67350 KG.

This result indicated that, even with maximum take-off thrust, the aircraft was overweight for a departure from A3 on runway 19L with the reduced runway length due to the displaced RWY 01R threshold.

Operator’s policies and flight procedures

Operations manual requirements

The operations manual detailed the operator’s general policies and specific procedures that governed the conduct of safe flying operations. With respect to the approach and pre‑flight phases of operations, it contained both common and specific requirements relevant to both. While the aircraft captain was accountable for the aircraft’s safety, and to obtain and check all available relevant information, the first officer was also required to be able to assume pilot in command duties should the aircraft captain become incapacitated. To meet this requirement, the first officer was to actively participate in the preparation and conduct of the flight, and in particular regarding flight preparation, to be familiar with all relevant operational information, including NOTAMs.

The operations manual also required both flight crew to independently review the weather information to be used in the departure and arrival preparations, such as that sourced from the ATIS. This independent review required each pilot to listen to the source information, or, if the source was a printed readout, independently read that data. That review was required to include verification of the information recorded on the take-off data card (TODC).

Flight crews were also required to be alert for NOTAMs that may have performance effect, but which did not have an FOE remark attached. The absence of the FOE remark identified that the NOTAM had not been assessed by FOE, and in such cases flight crews were required to contact flight dispatch and initiate an assessment of the NOTAM.

The manual also included a requirement for departure and arrival briefings. These briefings, which were normally conducted by the PF, had explicit content requirements, but both specifically included applicable NOTAMs. There was also a general threat and error management component to be addressed in these briefings.

Departure specific requirements

The pilot-in-command was responsible for ensuring that the aircraft’s gross weight was such that the flight could be conducted in compliance with the AFM, and similarly that the aircraft did not exceed take-off performance limitations. For take-off performance calculations, the operations manual required compliance with procedures that ensured an adequate independent cross-check be conducted with respect to several factors, including the input data used for the calculation. These independent cross-check procedures were detailed in the FCOM and the Performance and Loading Manual. Finally, the operations manual required specific items to be included within the departure briefing, when applicable. These items included any NOTAMs that were relevant to the departure.

Approach specific requirements

Before landing, the pilot in command was required to determine that the landing distance available (LDA) was sufficient and with an adequate safety margin. The operations manual provided 3 methods through which this determination could be made.

The first 2 methods were based on the dispatcher’s pre‑flight calculation of the landing weight limit for the sector. This limit was stated as the maximum landing weight (MLDW) in the limit weight (LIMIT WT) section of the OFP (Figure 3). If the aircraft’s landing weight was less than this MLDW:

- and there had been no adverse changes to the environmental conditions, aircraft configuration or runway of intended use, or

- having considered any changes to the environmental conditions, aircraft configuration and/or runway of intended use and found them to have no adverse effect,

then the landing distance requirement was met. Both MLDW methods were reliant on the flight crew knowing the variable parameters of environmental conditions, aircraft configuration and runway of intended use, that the dispatcher used in the MLDW calculation. Generally, dispatchers did not declare the parameters used in the MLDW determination within the OFP (see the section titled Flight planning). However, the dispatcher’s manual stated how these variable parameters were to be determined and flight crew could ascertain them from various parts of the FPP.

The third method required the flight crew to calculate an operational landing distance using maximum manual braking and factored by 1.15, and then ensuring that this landing distance was less than or equal to the LDA. The operations manual also required a stopping solution be determined when the LDA was sufficient. An operational landing distance calculation was made as part of the OPT’s en route landing performance solution (see the section titled En route landing performance calculator). Therefore, the sufficient LDA determination was met as part of the stopping solution calculation.

Training manual requirements

As the occurrence flight was also being used to support a training function (line flying under supervision), it was necessary to examine relevant training policy and guidance to determine any likely effect on the conduct of normal operations. The operator’s training manual stated that safety remained the primary objective of all training events, and that:

The safe conduct of our flying operations and all supporting activities relies on our systems, our operating procedures, and most importantly in the way we think and act.

The manual further stated that:

All flight crew and Training and Checking personnel engaged in … training and assessment activities are required to ensure that safety remains at the forefront of all actions and decisions. This is especially important for training conducted in the aircraft, where Trainers … must always ensure that the safety of the aircraft and its occupants is never compromised.

The training manual also stressed that training pilots should conclude all training events with some degree of debrief.

Flight procedures

Introduction

The procedures required of the flight crew for the various phases of flight were contained in the operator’s Flight Crew Operating Manual (FCOM). These procedures were to be performed by memory and ensured that operational systems were correctly configured for the relevant phase of flight, and data for the flight management systems was entered and correct. Pre and post‑flight duties were divided between the captain and first officer, while phase of flight duties were divided between the PF and PM.

The procedures required of the flight crew as part of the approach preparation for VA319, and those required as part of the departure preparation for VA324, are addressed separately. The FCOM procedures for both the approach and departure preparation required calculation of performance data. Those calculations, which were made using the OPT, were to be completed using procedures and guidance found in the aircraft Performance and Loading Manual.

Pre‑flight procedures and the performance data calculation

Take-off performance data calculations were part of the FCOM flight management computer’s (FMC) data entry procedure that was conducted in parallel with the captain and FO pre‑flight procedure. This procedure required the determination of input data for the performance calculation, recording of that data on the TODC, and entry of that data into the OPT. These procedures and method of calculation using the OPT were prescribed by the Performance and Loading Manual.

The pilot not performing the exterior inspection was required to complete the TODC. The weather conditions for the departure, such as that reported by the ATIS, and the input variables for the OPT calculation were to be determined and recorded onto the TODC. These included items such as:

- the relative wind (headwind or tailwind component)

- adjusted ambient temperature

- runway data to be used

- aircraft configuration data, such as the relevant weights, fuel on board, engine thrust rating, and the intended take-off flap setting.

These variables were then entered into the OPT and if a valid take‑off performance solution was calculated, the various take-off speeds, any take-off thrust derate (if applicable), and other performance data provided by the OPT calculation were to be recorded on the TODC (Figure 11).

Figure 11: A partial replication of the VA324 TODC

A partial replication of the VA324 TODC archived record, showing the recorded ATIS, aircraft weights, departure point and take-off performance data.

Source: Virgin Australia modified by ATSB

The take-off performance data was entered into the FMC as part of the data entry component of the pre‑flight procedure. The other pilot was then required to independently calculate the take-off performance data as part of their pre‑flight procedures.

Validating performance data calculations

The OPT had a ‘compare calculation’ function to compare the performance calculations made by 2 EFB devices connected through wi-fi. This ‘compare calculation’ function operated as the independent cross-check of input data required by the operations manual for all take-off performance calculations. The ‘compare calculation’ function displayed a comparison of the performance results and checked for any differences in the user inputs. Any discrepancies were notified to the user. Where no differences existed, both devices displayed a ‘check complete’ and ‘no mismatches found’ message.

Runway entry performance check

The FCOM’s before take-off procedures required the flight crew to verify that the runway about to be used for the take-off and the runway take-off position were correct. This was triggered when the aircraft was approaching the take-off position. It required, among other things, that the flight crew confirm that the runway location used for the performance calculation was coincident with the aircraft’s actual location.

Landing performance calculations

The OPT’s Landing En route Performance calculation, using the actual landing weight and the relevant weather components drawn from the ATIS, provided the operational landing distance for the various braking options (see the section titled En route landing performance calculator).

The landing distance available was also displayed, however, flight crews were not required to confirm that a changed landing distance available notified on the ATIS matched the landing distance available displayed on the OPT. This assurance was met through flight crew awareness and selection of the appropriate runway selection from the runway drop-down options in the OPT, which in turn was dependent on timely FOE updates to both the OPT database and notification to flight crew through the FPP.

Pre‑flight tasks and turnaround schedules

The operator provided a synopsis of the normal turnaround tasks and timings for a B737 flight crew. A turnaround was allocated 40 minutes from arrival to departure from the gate. The tasks required to be performed during the turnaround were estimated to take about 30 minutes, of which 4 minutes was assigned to planning the next sector. The operator noted that sector patterns were arranged such that ports were revisited, thereby enabling a significant part of the briefing process to be covered during an earlier cycle.

Air traffic control information

VA324 departure

Airservices Australia stated that several aircraft departed via the A3 intersection prior to the VA324 departure, and that there were no restrictions on doing so. The airport operator had installed several cones across the runway about 200 m south of the A7 taxiway intersection with the runway (Figure 12). VA324’s nose wheel was observed by the tower controller to lift at about taxiway A7 and the main wheels were observed to have passed extremely close to the displaced threshold cones. Several of the cones were blown over, and the airport operator advised that one cone was damaged.

In its internal investigation report, Virgin identified that some tower controllers were heard on the day, advising other flights that the runway was operating with a reduced length. Further, while acknowledging this was a non-standard radio call, the internal report also stated that consideration should be given to enhancing this radio call.

The ATSB determined that absence of such an alert for the VA324 departure was not contributory to the overrun occurrence. The shortened runway was included within the ATIS, which the flight crew acknowledged receipt of. Nevertheless, the inclusion of limiting runway conditions such as a shortened runway within the take-off clearance would enhance flight crew awareness of those conditions.

ATIS information

The ATIS information for both the arrival of VA319 and the departure of VA324 was ‘D’, which stated:

EXPECT INSTRUMENT APPROACH

RWY 19L AND R FOR ARRIVAL AND DEPARTURES

INDEPENDENT PARALLEL DEPARTURES IN PROGRESS

REDUCED RUNWAY LENGTH IN OPERATION RWY 19L, LANDING DISTANCE AVAILABLE 2689 M, TAKE OFF RUN AVAILABLE 2689 M

WIND 140 DEG, MIN 8 KT MAX 20 KT, CROSSWIND MAX 20 KT

VISIBILITY GREATER THAN 10 KM

SHOWERS IN AREA

CLOUD FEW 1500 SCT 3500

TEMPERATURE 22

QNH 1014

Recorded data

Recorded data from the aircraft’s flight data recorder, Automatic Dependent Surveillance Broadcast (ADS-B) data from Airservices Australia, and video from various aircraft gates around the airport, enabled the ATSB to determine where VA324 became airborne. The relationship between the point where the aircraft’s main wheels left the runway and the cones, as well as the declared distances stated in NOTAM YBBNC1174/22 are identified in Figure 12.

Figure 12: Runway 19L configuration for VA324 take-off

An image showing the location of the cones on runway 01R/19L, and also displaying the various distances notified through NOTAM YBBN 1174/22. Specific locations of VA324’s take-off are also displayed.

Source: ATSB

The Global Action Plan for the Prevention of Runway Excursions

In May 2021, EUROCONTROL, with the support of the Flight Safety Foundation, published the Global Action Plan for the Prevention of Runway Excursions (GAPPRE). This publication was the result of contributions from multiple international public and private organisations with the goal of enhancing the safety of runway operations. The GAPPRE recommendations represent industry best practice which extend beyond regulatory compliance.

As part of its examination of take-off performance data calculations, the GAPPRE made the following observations:

- Many runway safety events stem from erroneous or inadequate take-off performance calculations.

- While the independent take-off performance calculations by all active crew members, which are subsequently cross-checked, can be time consuming, it is highly recommended.

- EFB solutions incorporating navigational charts and applications for flight planning such as take-off and landing performance calculation programs not only save costs but also can simplify processes for flight crews. However, if threats such as runway shortening are not incorporated in time into the database used for performance calculations, the probability of the flight crew failing to detect such errors is high, especially as current NOTAM format and presentation in aviation in combination with fatigue, time pressure or complacency may lead to flight crews sometimes not reading or checking NOTAM information properly.

- Visualisation in particular is a great tool to enable flight crews to easily build a correct risk picture for their take‑off in terms of runway excursion prevention. Being aware of the additional stop margin resulting from their calculation and being able to easily cross‑check that the take‑off position and line-up procedure used for the calculation matches the one expected or used is key for flight crews’ safety-relevant decision-making (e.g. deciding on a re-calculation or accepting or rejecting line-up clearances). If technically feasible, visualisation of this information should therefore combine results of performance calculations and airport layouts.

These, and other observations with respect to the calculation of performance data, led to several recommendations, including that aircraft operators develop policies or standard operating procedures that require flight crews to perform independent performance calculations. This should include an independent cross-check of actual TORA/TODA from the AIS with the TORA/TODA used to calculate the take-off performance.

The implementation of this recommendation included a strategy that the actual TORA/TODA, especially if being altered by NOTAM, should be checked against the value used in the take-off performance program individually and independently by each flight crew member. If it is not technically feasible to combine the results of take-off performance calculations and airport/runway layout in one visualisation, at least the EFB solution should make it possible to visualise the available stop margin in relation to the TORA.

Operator processes

Virgin’s procedures did not require flight crew to confirm that the runway distance used in the performance calculation matched that stated on the aerodrome ATIS. The operator advised that the OPT and gross error checking systems currently used were satisfactory for runway performance calculations.

While the operator’s dispatch NOTAM update service and FOE review provided the latest information available for flight crew for use in runway performance calculations, it did not mitigate inadvertent flight crew error where FOE performance requirements were not identified as part of the briefing process. Further, while extremely remote, there is also the likelihood of late changes in runway configuration being reported on ATIS but being outside of any update to the NOTAM package being provided to flight crew. Both could lead to miscalculation of runway performance data, which could be mitigated through procedure requiring confirmation of an ATIS reported change in runway data being confirmed and matched to the data used in the performance calculation.

Similarly, tools that enable the visualisation of the relevant performance distances, and in particular the stopping margins available for the take-off, are of great value in enabling flight crews to easily build a correct risk picture for their take-off in terms of runway excursion prevention. While these visual tools were available for the OPT’s en route landing calculator, there was not an equivalent visual tool available for use in the take-off calculator.

Related occurrences

ATSB research and analysis report AR-2008-018

The first part of this 2-part ATSB research and analysis report presented a worldwide perspective of accidents and incidents involving take-off performance parameter errors. The report noted that, despite advanced aircraft systems and robust operating procedures, accidents continued to occur during the take-off phase of flight. The report documented accidents and incidents that resulted from take-off performance parameter data being incorrectly calculated or entered into aircraft systems.

It was found that calculation and entry of erroneous take-off performance parameters had many different origins, and that many factors were identified at all levels of influence. Due to the immense variation in the mechanisms involved in making take-off parameter calculation and entry errors, the report stated that there was no single solution to ensure that such errors were always prevented or captured. The report did, however, discuss several error capture systems that airlines and aircraft manufacturers can explore.

ATSB Investigation AO-2013-195

On 14 October 2013, a B737 aircraft departed from runway 11 intersection B2 at Darwin Airport using take-off performance data for the full runway length. The flight crew had prepared performance data for both a B2 intersection departure and a full-length departure and entered data for the full‑length departure into the flight management computer. As the aircraft taxied for a full-length departure, ATC advised of delays for a full-length departure due to arriving aircraft, but that an immediate departure was available from B2. The flight crew elected to use the B2 departure and reprogrammed the flight management computer. After a normal take-off, the flight crew identified that they had used the full-length data to reprogram the flight management computer, and that the aircraft had taken off with incorrect performance data.

ATSB Investigation AO-2021-037

During the month of September 2021, a NOTAM advised flight crew that Darwin Airport runway 29 had a displaced threshold due to runway works. Two flight crews, the first on 3 September and the second on 19 September, misinterpreted the NOTAM to mean that runway 11 threshold was displaced. Both flight crews planned for a displaced threshold landing on runway 11, and both crews subsequently landed long with reduced runway available for the landing roll. Further, both flight crews misinterpreted the aerodrome ATIS, which stated the active runway as being 11 and that the runway had reduced length.

NTSB Investigation NTSB/AIR-18/01

On 7 July 2017, an Airbus A320 was cleared to land at San Francisco airport runway 28R. The aircraft, which was conducting a visual approach to the runway, was lined up with the parallel taxiway C and not the runway. There were 4 air carrier aircraft waiting clearance to take off that were occupying taxiway C. The A320 descended to an altitude of 100 ft AGL before initiating a go‑around, during which the aircraft descended to 60 ft and overflew a number of the waiting aircraft, narrowly missing one of the waiting aircraft.

The flight crew aligned the aircraft with the taxiway on an incorrect understanding that the lights to their left were for the parallel runway 28L. That runway, however, was closed and not lit. A NOTAM stating the closure of runway 28L was included within the flight crew’s briefing package. The NTSB found several contributing factors to the runway misalignment, including that the flight operations information provided to the flight crew needed more effective presentation of information to optimise pilot review and retention of relevant information, particularly given the large volume of data presented to flight crew.

Safety analysis

Introduction

At 1148 on 30 November 2022, a Boeing 737-800 flight from Brisbane to Melbourne, operating as VA324, commenced its take-off run from the A3 intersection of runway 19L (RWY 19L) at Brisbane Airport (BNE). While the aircraft’s flight crew were aware of the upwind threshold being displaced, they were not aware that the take-off distance available for runway 19L had also been significantly reduced due to that displacement and that there were cones across the runway to mark the closed end of the runway.

Consequently, the performance data used for the take-off was incorrectly based on a normal length runway being available. This resulted in insufficient power being applied at the commencement of the take-off for the aircraft to complete the take-off in the declared distance available. This analysis will examine the factors that led to this serious incident and the opportunities to have corrected the misunderstanding of the runway status.

Flight planning in Melbourne

Incorrect mental model for runway 19L

Before the departure from BNE RWY 19L, the flight crew operated a sector from Melbourne (MEL) to BNE as VA319. The VA319 operational flight plan (OFP) component of the flight planning package (FPP) included a dispatcher’s note that identified that the threshold for BNE RWY 01R was displaced, but also contained the statement ‘NO LDW PERF LIMITATION’. This was intended to inform the flight crew that the displaced threshold had not led to any change to the aircraft’s maximum landing weight limitation for the landing into BNE.

The captain, however, misinterpreted this to mean that the displaced threshold had no performance effect for operations on runway 19L, that is, that flight operations engineering (FOE) had determined that there were no specific requirements with respect to the onboard performance tool (OPT) data input due to the threshold displacement. This misunderstanding led to a mental model that the displaced threshold for RWY 01R had no effect on performance requirements for RWY 19L.

Dismissing NOTAM YBBNC1174/22

The operator’s turnaround time between flights was generally scheduled at 40 minutes, of which about 5 was allocated to planning for the next sector. During this short period, there was typically a large volume of NOTAM data to be reviewed and flight critical data identified and actioned. While the grouping of sectors, revisiting of ports, and the use of a dispatcher to provide support, enabled efficiencies related to briefing, the aircraft captain retained overall responsibility for being aware of all relevant data.

To achieve this in the limited time available, the occurrence captain used NOTAM headlines as a guide to the content when assessing the relevance of a NOTAM. The scanning of NOTAMs using their heading is a practice often used by flight crew to enable large volumes of NOTAMs to be reviewed quickly. While the one subject matter and one condition standard for NOTAM construction generally supports this practice, there may be instances where a NOTAM’s headline does not fully reflect data contained within the free text section. NOTAM YBBNC1174/22 was one such NOTAM.

The 33-page VA319 FPP, which was presented to the flight crew in Melbourne, contained 120 NOTAMs over 18 pages. The NOTAMs for BNE included NOTAM YBBNC1174/22 with the headline RWY 01R THR DISPLACED. That NOTAM detailed the reduction in the runway length for operations on 01R/19L, data that was critical for the arrival into Brisbane. During review of the sector’s NOTAMs, the captain sighted the NOTAM headline and identified the NOTAM as being the matter to which the dispatcher had referred to in the note. However, the captain incorrectly dismissed this NOTAM as not being relevant to the flight because they:

- had previously incorrectly interpreted the dispatcher note on the performance effect of the displaced threshold, and therefore this NOTAM, as having no impact on their operations

- expected a landing on RWY 19L in Brisbane and the NOTAM headline made no reference to RWY 19L.

The ATSB was unable to conclusively determine whether the first officer reviewed the dispatcher’s notes and sector NOTAMs prior to departure from Melbourne, however, if they did, they missed the relevance of the note, the NOTAM and its attached FOE data.

FOE data not identified

The FPP was the only source available to the flight crew for notification of FOE data changes. Any performance calculation made without the use of the applicable FOE data had an elevated potential to be incorrectly applied. The FOE remark attached to YBBNC1174/22 contained the data necessary to select the correct OPT inputs and correctly calculate aircraft performance data when using the reduced length of runway 01R and 19L in Brisbane.

During the VA319 pre‑flight at MEL, the flight crew did not identify the FOE data applicable to operations on Brisbane’s RWY 19L during the review of the NOTAMs. The FOE data appended to NOTAM YBBNC1174/22 was either missed or dismissed due to an expectation that there was no performance effect.

The operator found that performance critical NOTAMs were presented in the same typeface as less critical NOTAMs and that this was contributory to the flight crew not identifying the FOE remark. While this is possible, it was also noted that the remarks were distinguished by a unique heading banner. The ATSB assessed that the incorrect mental model established by the captain was probably the overriding factor which influenced the dismissal of the NOTAM and its associated FOE remark.

Finally, the ATSB considered the possibility that the delayed issue of the complete FPP to the flight crew in Melbourne impacted the crew’s ability to effectively review NOTAMs and associated FOE. However, a full reprint of the FPP’s NOTAMs was available to the crew before departure and the preparations for arrival into Brisbane including the arrival briefing offered another opportunity to review the NOTAMs and identify applicable FOE data.

The Brisbane arrival

Readdressing the NOTAM

The operations manual requirements for an arrival briefing specified runway conditions and applicable NOTAMs for the arrival as items to be addressed in the briefing. It also included a general threat and error assessment for the arrival and landing. NOTAM YBBNC1174/22 contained critical information that merited review under both the briefing and the threat and error assessment.

However, contrary to these requirements, NOTAMs were not reviewed before arrival, nor were they reviewed when the time and opportunity was present during the en route phase of flight between MEL and BNE. While this time was likely allocated to training, the flight crew’s primary responsibility for safety of flight necessitated that, at a minimum, this NOTAM be reviewed. As a result, another opportunity to correct the captain’s (crew’s) mental model of BNE RWY 19 was missed.

ATIS and incorrect landing performance

While the BNE ATIS stated that the runway length of RWY 19L was reduced and specified the reduced landing distance available (LDA), the flight crew did not consider this notification to be relevant to the approach preparations. This was probably a result of the continuation of the misunderstanding of the dispatcher’s note regarding the performance requirements for RWY 19L. This resulted in the flight crew selection in the OPT of the full runway length for the runway input criteria, instead of the reduced length option. While the OPT landing performance data was based on an incorrect runway landing distance available, the calculated stopping solution was based on exiting the runway well before the closed section. Therefore, the landing was not affected by the incorrect runway data input. Further, the aircraft performed in accordance with the calculated data, exiting the runway normally using the planned rapid exit taxiway. The flight crew also did not see any visible restrictions or obstructions either on or around the runway which further supported their incorrect mental model.

While the LDA used in the landing performance calculation was displayed as part of the OPT en route landing performance calculation, the operator’s procedures did not require flight crews to crosscheck the LDA presented by the OPT with any notification of LDA change, such as that stated on the ATIS. Such a check, as recommended by the GAPPRE, could have provided an additional defence to capture the flight crew’s incorrect mental model and landing performance error.

The Brisbane departure

The pre‑flight

The flight crew commenced the pre‑flight preparations for VA324 with an understanding that YBBNC1174/22 did not impose any limitation on RWY 19L operations. Due to a combination of time pressures and distractions, particularly the delayed arrival into Brisbane and the initial prioritisation of training requirements during departure preparations, the flight crew had reduced time for their review of the VA324 FPP. As a result, the captain dismissed the dispatcher's note alerting the flight crew to the displaced threshold and, while the flight crew reviewed the OFP component of the briefing package prior to departure, they likely did not review the NOTAM package.

Take-off data error

Despite reviewing the ATIS content, due to an enduring belief there were no runway restrictions, the captain used an incorrect normal runway length input to determine the take-off performance figures for the BNE departure. This error was not identified as the first officer used the captain’s input data from the take-off data card (TODC), contrary to the independent take-off performance calculation procedures, resulting in the same incorrect figures.

Due to the use of the full runway length option as the basic runway configuration, the OPT calculator enabled a departure from the A3 intersection with a power derate. However, had the actual reduced runway length option (19L-WIPS) been used, the OPT would have excluded an A3 departure as the aircraft was overweight for such a departure, even with full take-off power. Further, had the A3 intersection departure selection been available for the 19L-WIPS option, the OPT would have notified the flight crew that a take-off from that point on the runway was not permitted.

Due to the incorrect take-off performance calculation, the aircraft did not meet the required performance for its departure from the A3 intersection of RWY 19L. The effect of this meant that the aircraft may have been unable to stop within the declared TORA if the take-off had to be rejected at high speed, and a runway excursion would have occurred. In addition, in the event of engine failure at high speed, the aircraft would probably have been unable to achieve its required performance.

Misleading MAGS

The Part 139 Manual of Standards required that movement area guidance signs (MAGS) located at runway intersection holding points be obscured when a temporarily displaced runway threshold altered the distance displayed by the MAGS. This did not occur while NOTAM YBBNC1174/22 was in effect. The signs presented a take-off distance that was in excess of that available, creating the potential to mislead flight crews about the status of the runway and the distance available when conducting a departure from that point.