Executive summary

What happened

On 16 November 2022, a non-scheduled passenger transport flight was conducted in a Cessna Citation Mustang, registered VH-IEQ, between Young Airport and Bankstown Airport, New South Wales. On board were a pilot and one passenger.

As the aircraft approached Bankstown Airport to land under the instrument flight rules, about 10 minutes after last light, the pilot established contact with air traffic control (ATC), where a ‘visual’ approach was requested. ATC approved the pilot to fly directly toward final approach for runway 11 centre. Immediately after this clearance, the pilot started tracking toward final approach for this runway and descended to a height of 1,000 ft, which was about 800 ft below the lowest safe altitude for the area. ATC subsequently issued a terrain safety alert. An uneventful landing was conducted at 2020 local time.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that the pilot had submitted a flight plan earlier in the day for an arrival after last light, when more stringent rules applied than day operations. However, the pilot followed the rules applicable to day operations as there was still some ambient light available to allow features on the ground to be visually identified and avoided. This resulted in the pilot descending below the lowest safe altitude applicable for operations at night.

Safety message

This incident highlights the importance of planning, particularly around times when rules change, such as the transition from day to night. In this case, the pilot reported that flying a published instrument approach procedure, rather than declaring ‘visual’ would have been a more suitable plan for this flight.

The investigation

| Decisions regarding the scope of an investigation are based on many factors, including the level of safety benefit likely to be obtained from an investigation and the associated resources required. For this occurrence, a limited-scope investigation was conducted in order to produce a short investigation report, and allow for greater industry awareness of findings that affect safety and potential learning opportunities. |

The occurrence

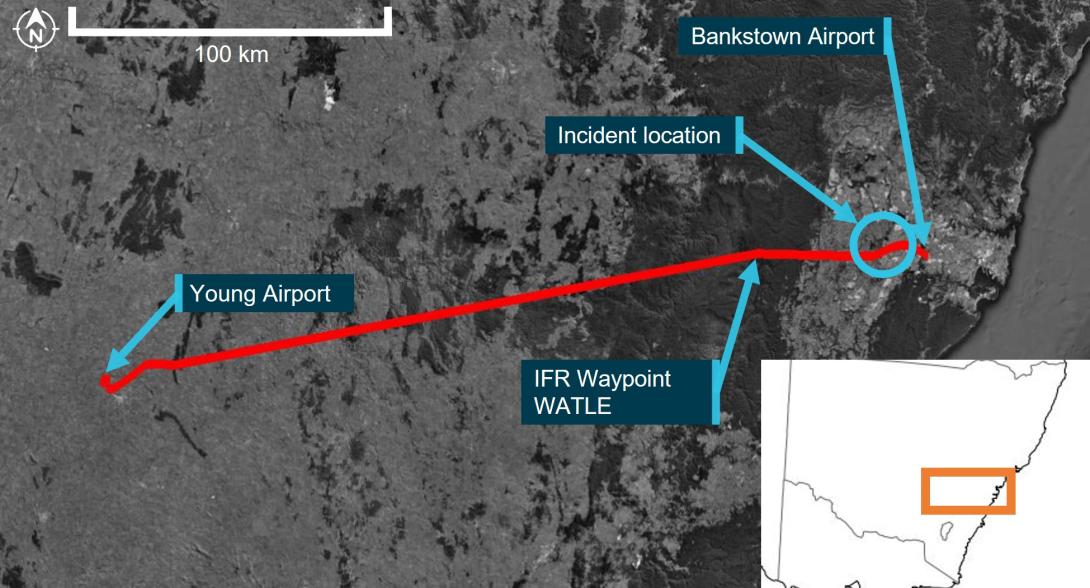

In the late afternoon of 16 November 2022, a non-scheduled passenger transport flight was conducted in a Cessna Citation Mustang, registered VH-IEQ (IEQ) between Young Airport and Bankstown Airport, New South Wales (Figure 1). On board were a pilot and one passenger.

This was the fourth and final flight of the day, with the pilot completing 3 earlier flights in the aircraft. National Airspace Information Planning System records indicated that the pilot submitted all flight plans for these flights at about 0448 local time, with this plan showing a planned departure from Young at about 1945 for the incident flight. This flight was planned to follow flight routes under the instrument flight rules (IFR)[1] and arrive at Bankstown at about 2014.

Figure 1: Flight path of VH-IEQ and incident location

Image showing flight path of aircraft (red line) on a map, with take-off, arrival and location of flight below lowest safe altitude.

Source: Google Earth and Geoscience Australia, annotated by the ATSB

Flight data recorded by the GPS navigation unit onboard the aircraft indicated that a take-off was commenced from Young on runway 19 at about 1946. After take-off, the aircraft started tracking to the east and climbed to a cruising altitude of flight level (FL)[2] 230 by about 1956.

At about 2001, the aircraft started to descend, continuing to track toward IFR waypoint WATLE. During this descent, at about 2004, last light[3] for Bankstown occurred. Six minutes later, the aircraft arrived overhead WATLE and proceeded to follow the planned IFR route denoted ‘Y20’, directly toward Bankstown Airport, 28 NM (52 km) to the east. At 2014:48, at waypoint NOLEM (Figure 2), the aircraft levelled out at 2,000 ft[4] above mean sea level and continued to track toward Bankstown. At this time, the pilot established first contact with Bankstown Tower air traffic control (ATC) near waypoint NOLEM (Figure 2), with the following communication exchange:

2014:48 IEQ: ‘Bankstown tower IEQ is 11 miles west 2,000 with Quebec visual inbound’

2014:59 BANKSTOWN TOWER: ‘IEQ BK TWR Join Final Runway 11 centre’

2015:08 IEQ: ‘Join Final 11 centre IEQ’

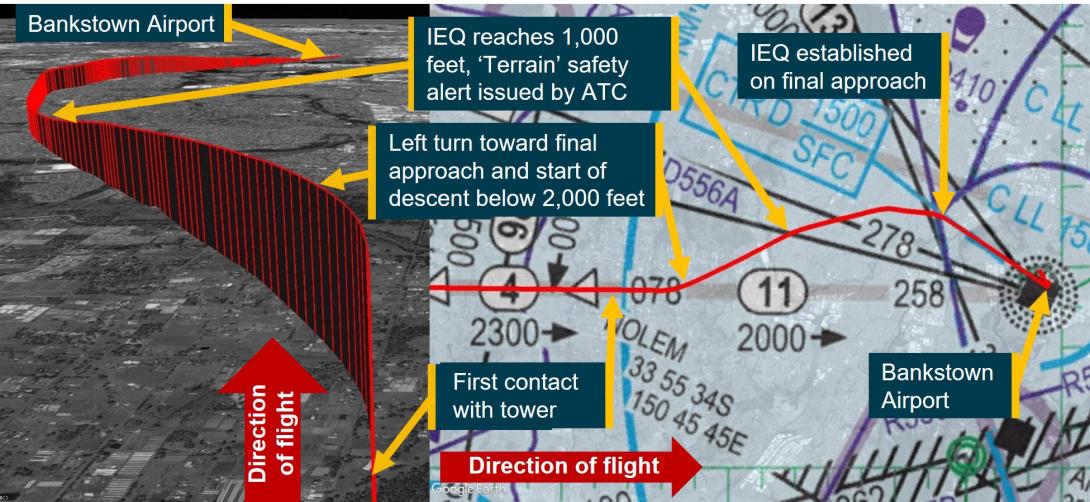

Immediately after responding to ATC, flight data indicated that the aircraft began a left turn onto a track of approximately 060° (true). Near the completion of the left turn, at 2015:22, the aircraft began to descend from 2,000 ft (labelled ‘left turn toward final approach and start of descent below 2,000 feet’ in Figure 2). The aircraft continued to descend on this track, levelling out at 1,000 ft at 2016:20. Around this time, ATC identified that the aircraft was ‘too low’, and issued a ‘Terrain’ safety alert at the location marked in Figure 2. The communication exchange for the safety alert between ATC and the pilot were as follows:

2016:30 BANKSTOWN TOWER: ‘IEQ Safety Alert Terrain QNH[5] is 1012’

2016:38 IEQ: ‘Roger copy 1012 IEQ I'm ahh visual’

2016:43 BANKSTOWN TOWER: ‘IEQ’

At the time the safety alert was issued and while maintaining at 1,000 ft, flight track data showed that the aircraft started to change track to the right by 15° to 075° for about 2 NM (3.7 km). The aircraft then changed track again to the right toward the intersection of the Bankstown Airport control zone and the extended centreline of runway 11 centre. Just prior to entering the control zone at 2017:55, Bankstown Tower provided the aircraft with a clearance to land, which was acknowledged by the pilot. At this time, the aircraft turned toward runway 11 centre and started to descend from 1,000 ft. An uneventful landing on runway 11 centre was conducted at 2019:56.

Figure 2: Flight path of VH-IEQ showing descent to 1,000 ft and approach to land

Note: Image showing flight path of aircraft (red line) on a low level enroute chart (right) and from the perspective of the approach from the NOLEM waypoint (left).

Source: Google Earth and Airservices Australia, annotated by the ATSB

Context

Meteorological information

The meteorological report (METAR)[6] for Bankstown Airport released at 2000 local time indicated the following weather conditions for the aircraft’s arrival:

- winds at 6 kt from the north-west

- visibility greater than 10 km

- 3 layers of cloud, comprising scattered[7] at 5,100 ft and at 7,000 ft, and broken at 8,200 ft above the ground

- the QNH was 1012 hPA.

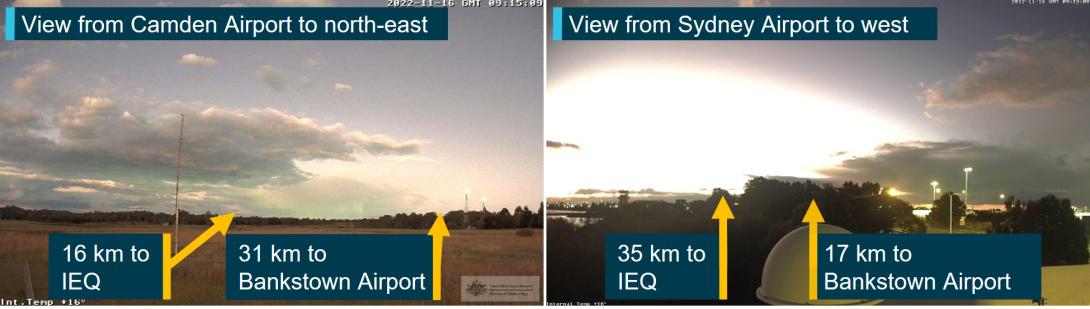

Images from weather cameras at the time of the incident located at Camden and Sydney Airports facing the direction of the aircraft and Bankstown Airport are shown in Figure 3. The images show that less than half of the sky is covered by cloud, with the cloud tops illuminated by the sun. There were no weather cameras operating at Bankstown Airport.

The Bureau of Meteorology advised that these weather cameras were configured 'to work in low light and will use the light available to provide the best image’, that is, the images shown in Figure 3 ‘look brighter than the actual conditions experienced by the pilot’. However, relatively clear atmospheric conditions are shown by the images, with well-defined silhouettes of ground‑based features.

Figure 3: Images from weather cameras at Camden and Sydney Airports

Source: Bureau of Meteorology, annotated by the ATSB

Visual approach to Bankstown Airport

During the approach, the pilot advised ATC that they were ‘visual’. This transmission signified that the requirements for a visual approach under the IFR could be met. ATC responded providing an instruction to ‘join final 11 centre’, which constituted a clearance to enter the Bankstown control zone on the centre line of runway 11 centre, tracking toward that runway.

As last light was at 2004 and this instruction was provided at 2014, this meant that the visual approach requirements for IFR flights by night applied.

To assist with conducting the visual approach, runway 11 centre was equipped with a precision approach path indicator system.[8]

Required actions by pilot following instructions from ATC

AIP ENR 1.1 paragraph 2.2.7.2[9] (Operations in Class D Airspace)[10] stated that in circumstances where ATC responds with the aircraft callsign and instructions, the pilot must comply with ATC instructions. It also states that ‘when no level instruction is issued’, the pilot may ‘descend as necessary to join the aerodrome traffic circuit’. In this case, ATC had instructed the pilot to join final runway 11 centre without a level instruction. The instructions meant that the pilot was required to fly the aircraft to enter the Bankstown control zone on the extended centreline for runway 11 centre. However, minimum height requirements applied to the flight as discussed in the next section.

Minimum height requirements during a visual approach for an IFR flight at night

During a visual approach at night, subparagraph 91.305(3)(b)(i) of the Civil Aviation Safety Regulations 1998 (CASR 91.305(3)(b)(i)) allowed an IFR flight to descend below minimum stipulated heights if the aircraft was being flown in accordance with:

…requirements relating to visual approach or departure procedures published in the authorised aeronautical information for the flight.

AIP ENR 1.5 section 1.14 articulated these requirements. AIP ENR 1.5 paragraph 1.14.6(b)[11] was relevant to this flight and included the provision that the pilot may visually approach the aerodrome by night when at an altitude not below the lowest safe altitude (LSALT)[12] or minimum sector altitude (MSA)[13] for the route segment, if the aircraft was established:

(1) clear of cloud;

(2) in sight of ground or water;

(3) with a flight visibility not less than 5,000M; and

(4) subsequently can maintain (1), (2) and (3) at an altitude not less than:

…

(ii) one of the following:

Route segment LSALT/MSA; or…

Based on the reported weather conditions, clauses 1, 2 and 3 noted above were achieved when the request for a visual approach was made by the pilot to ATC. Further, the AIP stipulated one of the conditions allowing an aircraft to descend below LSALT was when the aircraft was:

Within 5NM (7NM for a runway equipped with an ILS/GLS) of the aerodrome, aligned with the runway centreline and established not below “on slope” on the T-VASIS or PAPI;

Based on the ATC clearance provided to the pilot, and runway 11 centre being equipped with a PAPI, this meant that the aircraft could descend below LSALT once aligned with the runway centreline and not below on-slope of the PAPI and within 5 NM (9.3 km) of the PAPI.

Calculation of the lowest safe altitude

Flight data showed that after the initial climb from Young Airport, the aircraft had been above the published LSALT for the duration of the flight until reaching waypoint NOLEM.

AIP GEN 3.3 section 4 defined how to calculate the LSALT. Specifically, paragraph 4.2 stated:

For routes and route segments not shown on AIP aeronautical charts, the lowest safe altitude must not be less than that calculated in accordance with para 4.3 within an area defined in the following paras 4.6, 4.7, 4.8 and 4.9.

For this flight, paragraph 4.3 clause 4.3(a) stated the LSALT was to be calculated using the following method:

Where the highest obstacle is more than 360FT above the height determined for terrain, the LSALT must be 1,000FT above the highest obstacle; …

Additionally, paragraph 4.5 stated:

If the navigation of the aircraft is inaccurate, or the aircraft is deliberately flown off-track, or where there is a failure of any radio navigation aid normally available, the area to be considered is a circle centred on the DR position, with a radius of 5NM plus 20% of the air distance flown from the last positive fix.

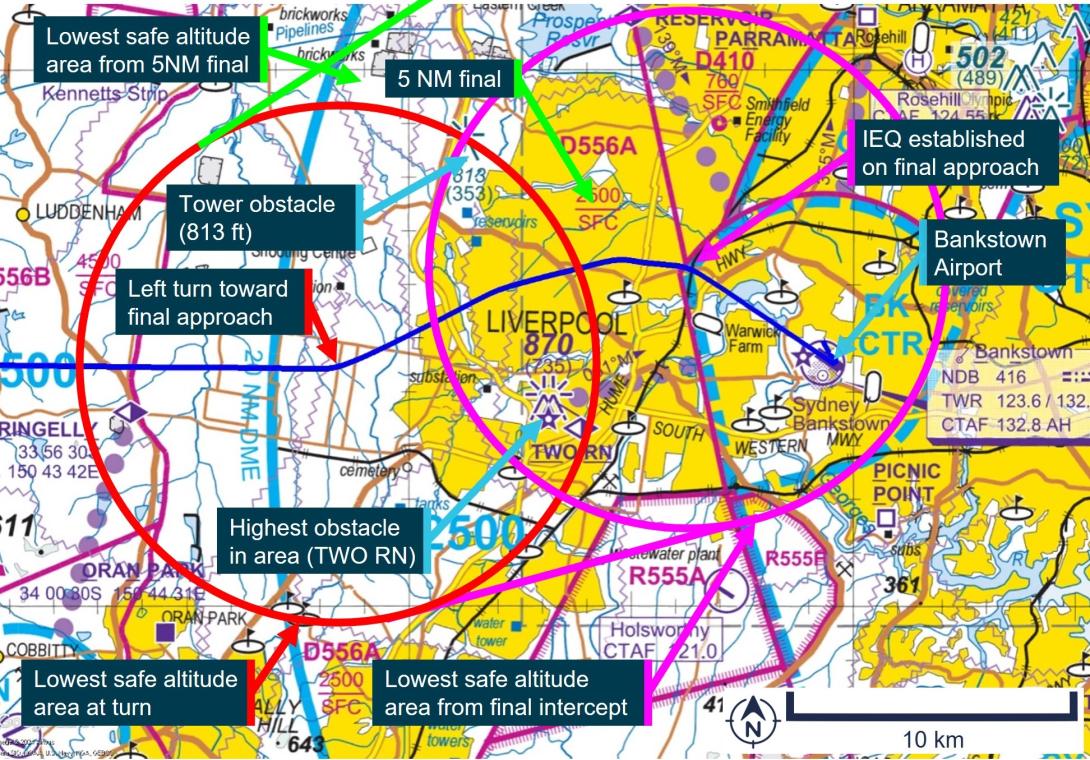

Paragraph 4.5 applied to the incident flight after the pilot intentionally flew off-track toward final approach for runway 11 centre with the last positive fix being the waypoint NOLEM. Based on this, the ATSB calculated the LSALT for the aircraft between NOLEM and being aligned with runway 11 centre. An extract of the visual terminal chart applicable to the area is shown in Figure 4.

The aircraft was equipped with an approved global navigation satellite system, which was being used for navigation under RNP 2[14] meaning that the aircraft remained with a positive fix for the duration of the flight. For RNP 2 operations, AIP GEN 3.3 paragraph 4.7 required the following area to be considered for LSALT calculations:

…within an area of 5NM [9.3km] surround and including the departure point, the destination and each side of the nominal track.

This area is shown for the incident between the red circle labelled ‘Lowest safe altitude area at turn’ and the magenta circle labelled ‘Lowest safe altitude area from final intercept’ in Figure 4. Calculations were also performed in the circumstance where the aircraft flew to an extended 5 NM final for runway 11 centre, the earliest point of descent when using the PAPI, and this is depicted by the green circle labelled ‘Lowest safe altitude area from 5 NM final’ in Figure 4.

Figure 4 also shows 2 charted obstacles in the area. This indicated that paragraph 4.3(a) from AIP GEN 3.3 applied to this part of the flight. The highest obstacle in the area to be considered for LSALT was the tower ‘TWO RN’ at 870 ft above mean sea level, located about 2.5 NM (4.6 km) to the right of track, as labelled in Figure 4. Another tower was present about 2.5 NM (4.6 km) to the left of track at a height of 813 ft. Based on this, the LSALT for the aircraft during this segment of the flight was 1,870 ft.

Figure 4: Area applicable to lowest safe altitude calculations for VH-IEQ between flight path deviation and the extended centreline of runway 11 centre at Bankstown Airport

Source: Airservices Australia, annotated by the ATSB

Lowest safe altitude for a visual approach during the day

AIP ENR 1.5 section 1.14 paragraph 1.14.6(b) stipulated the same requirements for a visual approach by an aeroplane in the day, except for clause (4)(ii), which required pilots to maintain an altitude not less than:

The minimum height prescribed by CASR 91.265 or 91.267 as relevant to the location of the aircraft.

For the location of this incident, regulation 91.265 for flights over ‘populous areas and public gatherings’ applied. This stipulated that the aeroplane must be flown more than 1,000 ft above the highest feature or obstacle within a horizontal radius of 600 m of the point on the ground or water immediately below the aeroplane. Based on this, the height flown by the aircraft was above that required for an IFR visual approach during the day.

Decision to descend below lowest safe altitude

During an interview with the ATSB, the pilot recalled the following observations about the navigation conditions during the approach:

- It was a light evening with plenty of twilight allowing the ground to be seen clearly.

- The light was sufficient to see a clear horizon.

- Ground features were able to be clearly seen, sufficient to identify the aircraft’s precise position.

- All known obstacles could be seen.

Based on these observations, the pilot reported deciding to ‘call visual’.

The pilot’s description of the weather conditions was consistent with those recorded by the Bureau of Meteorology.

The pilot stated that, during a self-briefing prior to departure, the time of last light had been recorded for Young Airport and not Bankstown Airport as intended. The pilot also reported reviewing the last light time prior to descent to Bankstown Airport. Last light at Young Airport occurred about 12 minutes later than Bankstown Airport due to it being further west. The pilot later stated that recording the last light time for Young instead of Bankstown in the briefing sheet possibly contributed to the decision to descend and conduct the approach flown.

The pilot stated that descending to 1,000 ft assisted with meeting the stabilised approach criteria, which was:

“in a landing configuration with gear down, full flap, the sink rate … under 1,000 feet per minute and the checklists … completed…by 1,000 feet”.

The pilot stated that a challenge with using the PAPI was not being able to descend until 5 NM (9.3 km) from the runway, and that this was up to 1,000 ft higher than the ideal glideslope of about 1,600 ft at that location if the minimum sector altitude of 2,500 ft was used. The pilot also stated:

“the aircraft will then give you a lot of warnings about sink rate and terrain which can be very stressful… for passengers”.

For these reasons, the pilot stated:

“that is why I elected to descent to make sure that I was able to get that stabilised approach criteria. And …, it only worked because I had such good visibility in the twilight, I was able to see the ground, and I was able to see visually where I was.”

The pilot also stated that a motivation for declaring visual was to ‘fit in’ with the other traffic in the Bankstown area. However, the pilot stated that, on reflection, flying an instrument approach (specifically the RNP approach, rather than declaring visual) would have been a better solution for arriving close to or after last light for the aircraft stating:

“the only way to do it to achieve the stabilised approach is by the RNP”.

Fatigue considerations

The ATSB evaluated the likelihood that the pilot was fatigued at the time of the incident. Some areas of increased risk of fatigue potentially relevant related to:

- continued period of wakefulness/length of duty period

- split duty and efficacy of naps

- quantity of sleep, particularly relating to early starts.

The pilot reported obtaining 7.5 hours of sleep immediately prior to the incident, and 8 hours for each of the 2 nights prior to that. The pilot submitted a flight plan at 0448 and was likely awake for some time prior to this. The pilot’s flight duty period (FDP) for the day started at 0630,[15] had a split duty rest period between 1030 and 1730 that included a 1-hour nap, and then was on duty again until 2100. As the incident occurred at 2016, the pilot’s total FDP was 14 hours and 30 minutes, which was 30 minutes over the maximum allowed under Appendix 4 of Civil Aviation Order 48.1 for single-pilot air transport operations, or to an approved fatigue risk management system. However, section 5.3 of Appendix 4 stated:

Despite the FDP limits provided in the operations manual, in unforeseen operational circumstances at the discretion of the pilot in command, the FDP limits in the operations manual may be extended by up to 1 hour.

The pilot reported having a discussion with the chief pilot about extending the FDP limits due to floods in the area delaying the departure time for the flights. However, the final flight of the day arrived within 5 minutes of the planned time.

Based on the reported sleep obtained, the pilot was likely not fatigued at the time of the incident.

Safety analysis

After last light, the pilot contacted Bankstown Tower declaring that they were ‘visual’ at 2,000 ft. This signified to ATC that requirements for a visual approach at night under the IFR could be achieved. The controller’s subsequent instruction to join final runway 11 centre indicated that the pilot could track toward the extended centreline for that runway.

The clearance from ATC did not specify an altitude, allowing the pilot to descend to the LSALT until established within 5 NM (9.3 km) of the PAPI for runway 11 centre. However, immediately after this clearance, the pilot descended to 1,000 ft, below the LSALT of 1,870 ft. This LSALT applied due to the 2 towers in the area rising to a height of 870 ft about 2.5 NM (4.6 km) from the aircraft. Analysis by the ATSB showed that flight above the LSALT could have been achieved by maintaining altitude between the point of diversion until being aligned with the extended centreline of runway 11 centre within 5NM (9.3 km) of the PAPI.

The pilot reported that the actual approach flown was as they had planned and declared ‘visual’ as they could ‘see the obstacles’. Weather camera imagery showed that the conditions were consistent with the pilot’s description. However, the camera imagery was likely brighter than that experienced by the pilot from altitude looking down on the obstacles and terrain. In this case, the flight path flown by the pilot was applicable and suitable for operations in the day. However, both the planned and actual times when the flight below LSALT occurred were after last light, based on the elapsed time between first contact with ATC and landing. Further, the pilot also reported incorrectly recording a later time for last light than actual, based on Young instead of Bankstown. The additional perceived duration of usable light possibly contributed to the decision to conduct the approach flown. The pilot reported that, on reflection, a better option would have been to fly an instrument approach procedure when planning to arrive at Bankstown just prior to or after last light. This indicated that these requirements could have been considered prior to the flight and represented a missed opportunity during flight planning.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the flight below minimum altitude involving Cessna Citation 510, VH-IEQ, 13 km west of Bankstown Airport, New South Wales, on 16 November 2022.

Contributing factors

- While conducting a visual approach to Bankstown Airport, the aircraft descended 800 ft below the lowest safe altitude for operations at night, reducing the assurance for separation from terrain and ground-based obstacles.

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- the pilot

- Airservices Australia

- recorded data from the GPS unit on the aircraft.

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- the pilot

- Navair Flight Operations Pty Ltd

- the Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Airservices Australia.

Submissions were received from:

- the pilot

- the Civil Aviation Safety Authority.

The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2024

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] Instrument flight rules (IFR): a set of regulations that permit the pilot to operate an aircraft to operate in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC), which have much lower weather minimums than visual flight rules (VFR).

[2] Flight level: at altitudes above 10,000 ft in Australia, an aircraft’s height above mean sea level is referred to as a flight level (FL). FL 230 equates to 23,000 ft.

[3] Last light is defined as the end of evening civil twilight, marking the commencement of night. The end of evening civil twilight occurs when the Sun’s centre is 6° below the horizon.

[4] This was also the published lowest safe altitude between IFR waypoint NOLEM and Bankstown Airport.

[5] QNH: the altimeter barometric pressure subscale setting used to indicate the height above mean seal level.

[6] METAR: a routine aerodrome weather report issued at routine times, hourly or half-hourly.

[7] Cloud cover: in aviation, cloud cover is reported using words that denote the extent of the cover – ‘scattered’ indicates that cloud is covering between a quarter and a half of the sky, and ‘broken’ indicates that more than half to almost all the sky is covered.

[8] Precision Approach Path Indicator (PAPI): a ground-based system that uses a system of coloured lights used by pilots to identify the correct glide path to the runway when conducting a visual approach.

[9] AIP ENR 1 GENERAL RULES AND PROCEDURES, section 1.1 GENERAL RULES, subsection 2 OPERATIONS IN CONTROLLED AIRSPACE, sub subsection 2.2 Air Traffic Control Clearances and Instructions

[10] Class D: This is the controlled airspace that surrounds general aviation and regional airports equipped with a control tower. All flights require ATC clearance.

[11] AIP ENR 1 General Rules and Procedures, section 1.14 Visual Approach Requirements for IFR flights, subsection 6, sub subsection 6(b) Visual approach by Night, dated 02 DEC 2021.

[12] Lowest safe altitude (LSALT): The lowest altitude that provides safe terrain clearance at a given place.

[13] Minimum sector altitude (MSA): The lowest altitude that will provide a minimum clearance of 1,000 ft above all objects located in an area contained within a circle or a sector of a circle of 25 NM (46 km) or 10 NM (19 km) radius centred on a significant point.

[14] Required navigation performance (RNP) levels refer to the performance required from the navigation system. RNP 2 is primarily used in continental airspace where there is some ground navigation aid infrastructure.

[15] A flight duty period starts when ‘a person is required by an AOC [Air Operator’s Certificate] holder to report for a duty period in which 1 or more flights as an FCM [flight crew member] are undertaken’. The flight plan submission at 0448 was therefore not counted as duty (only time awake).