Executive summary

What happened

On the morning of 18 July 2022, a Kavanagh E-260 hot air balloon, registered VH-FSR (FSR) and a Kavanagh B-400 hot air balloon, registered VH-OOP (OOP) were being operated on a balloon transport flight about 6 km south‑east of Alice Springs Airport. Both balloons were operated by Red Centre Ballooning.

At 0700, FSR was flying at about 900 ft above ground level (AGL) within a faster north-easterly wind, while about 1,150 m ahead, OOP was at about 100 ft AGL within a slower westerly wind.

At that time, the pilot of FSR decided to descend to the lower-level wind (below 200 ft AGL) to slow the balloon. Before descending, the pilot of FSR incorrectly judged OOP to also be flying in the higher, faster wind and assessed that FSR would descend behind OOP while maintaining sufficient separation.

During the descent, the pilot of FSR realised that OOP was flying lower and more slowly than initially assessed and recognised that a collision was possible. The pilot of FSR was aware that a basket to envelope collision carried the risk of tearing the envelope of the lower balloon and controlled the descent so that any collision would be between the balloon envelopes.

At 0702, the two balloons collided close to the widest point of each envelope. The balloons were not damaged and there were no injuries. After the collision, the balloons separated, and the flights continued without further incident.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that while attempting to descend to a position behind OOP, the pilot of FSR misjudged the speed and direction of OOP and descended FSR toward OOP. After recognising that a collision was likely, the pilot of FSR then managed the balloon's descent so that a basket did not collide with an envelope, reducing the risk of damage.

What has been done as a result

The operator has educated all company pilots on radio and passenger communications and close proximity balloon operations.

Safety message

While in this case, the pilots were able to avoid damage during the collision, this incident highlights the importance of evaluating all available options to support good decision making. The Civil Aviation Safety Authority Resource booklet Decision Making provides the following tips to improve the quality of decision making:

- You cannot improvise a good decision, you must prepare for it. You will make a better and timelier final decision if you have considered all options in advance.

- Always have reserve capacity for reacting to unexpected events.

- Where possible, advise others of your plans before you act. This increases the chances of successful follow through on your decision and ensures people are not caught unaware.

- When time is not so critical, involve others in the decision making. That way everybody is more invested in the decision and therefore are likely to be more motivated to support it.

This incident also highlights the risks of misinterpreting what is seen. The Civil Aviation Safety Authority Advisory Circular AC 91-14 Pilots' responsibility for collision avoidance provides guidance for collision avoidance including:

Not only is seeing important, but accurately interpreting what is seen is equally vital.

The investigation

The occurrence

On the morning of 18 July 2022, the pilot of a Kavanagh E-260 hot air balloon, registered VH-FSR (FSR) and the pilot of a Kavanagh B-400 hot air balloon, registered VH-OOP (OOP) prepared to depart a launch site 7 km south‑east of Alice Springs Airport for a balloon transport flight.[1] Both balloons were operated by Red Centre Ballooning.

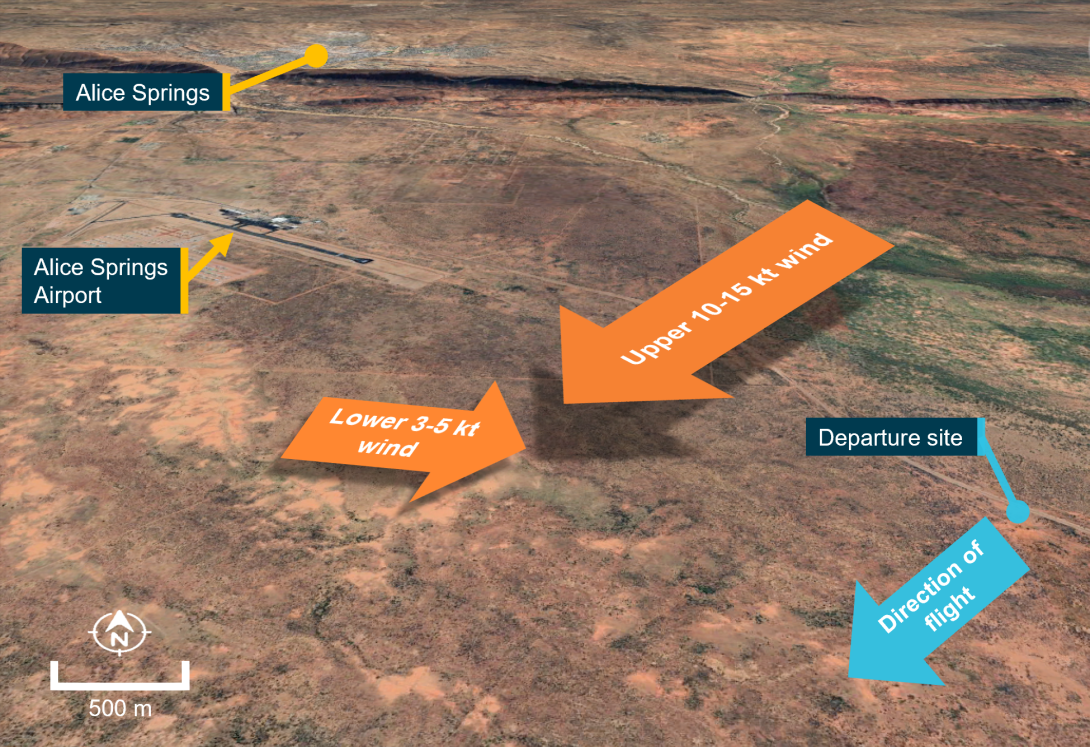

Before departing, the pilots released a pilot balloon[2] to determine wind conditions. The pilots observed that up to about 200 ft above ground level (AGL) a 3‑5 kt westerly wind prevailed. Above this was a 100 ft thick layer of calm air. Extending above the calm layer was a north‑easterly wind of about 10‑15 kt (Figure 1). The pilots also noted that cloud and visibility conditions were clear.

Figure 1: Departure site and prevailing winds

Source: Google Earth, annotated by ATSB

Both balloons departed at about 0645 local time. On board FSR was a pilot and 10 passengers, while OOP had a pilot and 23 passengers on board.

At about 0700, FSR was flying at about 900 ft above ground level (AGL) within the faster north‑easterly wind, while 1,150 m ahead, OOP was at about 100 ft AGL within the slower westerly wind. At about this time, the pilot of FSR decided to descend to the lower-level wind (below 200 ft AGL) to slow the balloon.

Before descending, the pilot of FSR incorrectly judged OOP to also be flying in the faster wind. Consequently, the pilot of FSR assessed that FSR would descend behind OOP with sufficient separation and made a radio broadcast using an ultra-high frequency (UHF) radio advising of the descent. The pilot of FSR did not confirm that the pilot of OOP had received and understood the broadcast.

During the descent, the pilot of FSR realised that OOP was flying lower and more slowly than initially assessed. When the distance between the two balloons reduced to about 250 m, the pilot of FSR recognised that a collision was possible.

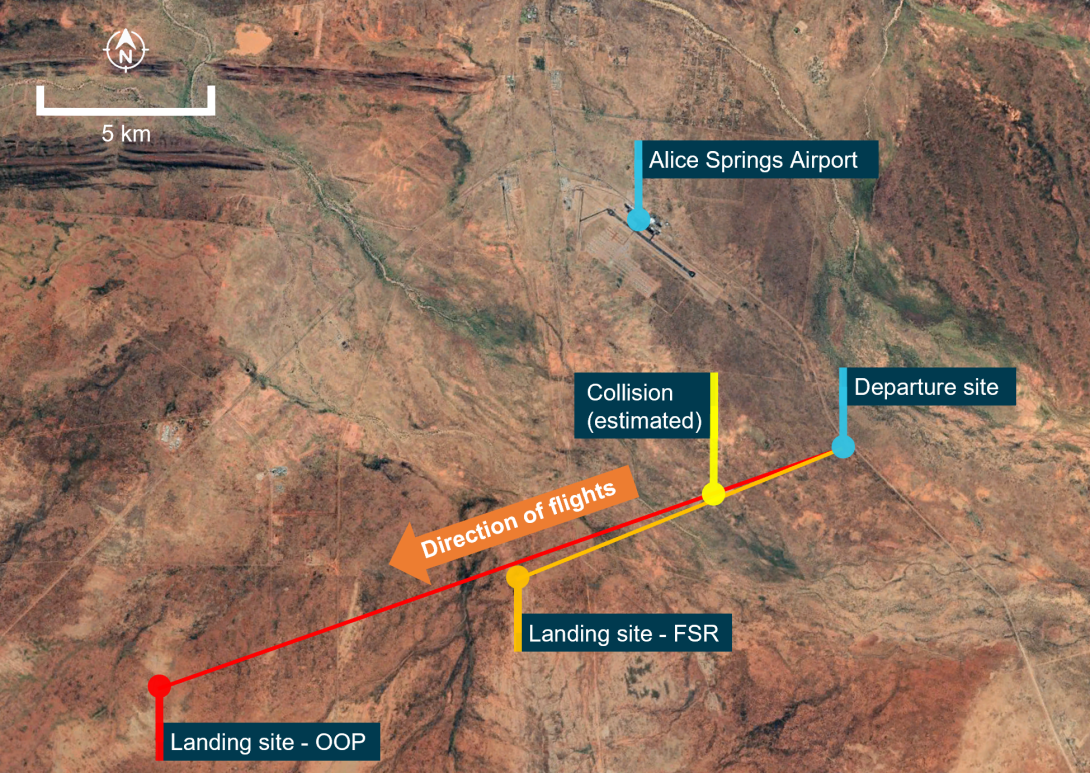

About 40 seconds before the eventual collision, the pilot of OOP observed FSR closing and recognised the potential for contact (Figure 2), so called the pilot of FSR 4 times using a UHF radio. During that time, the pilot of FSR was focussed on managing the descent and misinterpreted these broadcasts as communications between other balloons that were operating in the area and therefore did not reply.

Figure 2: Overview of flights

Note: The balloon flightpaths were not recorded, the tracks depicted are representative only of the overall flights.

Source: Google Earth and operator, annotated by ATSB

The pilot of FSR was aware that a basket to envelope collision carried the risk of tearing the envelope of the lower balloon and so attempted to control the descent such that any collision would be between the balloon envelopes. FSR continued to decelerate slowly, but the balloon’s momentum continued to carry it toward OOP. To minimise the risk of envelope to basket contact, the pilot of OOP attempted to maintain a steady altitude. As FSR closed on OOP, the pilot of OOP alerted the passengers to the likely collision.

At 0702, the two balloons collided close to the widest point of each of their envelopes (Video 1). The balloons were not damaged and there were no injuries. After the collision, the balloons separated, and the flights continued without further incident.

Video 1: The collision

Source: Passenger aboard FSR

Context

Pilot information

The pilot of FSR held a Commercial Pilot Licence (Balloon) valid for Class 1 and Class 2 balloons.[3] At the time of the occurrence the pilot had accrued a total flying time of 1,010 hours, with 258 hours on the E-260 hot air balloon (Class 2). The pilot also held a current CASA Class 2 aviation medical certificate.

The pilot of OOP was the operator’s Head of Operations and also held a Commercial Pilot Licence (Balloon) valid for Class 1 and Class 2 balloons. At the time of the occurrence the pilot had accrued a total flying time of about 4,415 hours, with about 600 hours on the B-400 hot air balloon (Class 2). The pilot held a current CASA Class 2 aviation medical certificate.

A review of both pilots’ activities over the 72 hours prior to the occurrence identified that it was unlikely that either pilot was experiencing a level of fatigue known to affect performance.

Aircraft information

VH-FSR was a Kavanagh Balloons E-260 hot air balloon manufactured in 2009. The E‑260 balloon had an envelope capacity of 260,000 cubic feet (7,362 cubic meters) and a maximum take-off weight of 2,184 kg.

VH-OOP was a larger Kavanagh Balloons B-400 hot air balloon. The B‑400 balloon had an envelope capacity of 400,000 cubic feet (11,327 cubic meters) and a maximum take-off weight of 3,100 kg.

Airspace

The incident occurred within Alice Springs airspace. At the time of the incident, the control tower was not active, and the airspace was operating as class G airspace, utilising a common traffic advisory frequency.

Communications and collision avoidance

The balloons were equipped with both very-high frequency and ultra-high frequency (UHF) communications radios.

The Civil Aviation Safety Regulation (CASR) Part 91 Manual of Standards, Chapter 21 stated that when in the vicinity of a non-controlled aerodrome, a pilot must make a broadcast when the pilot ‘considers it reasonably necessary to broadcast to avoid the risk of a collision with another aircraft’.

The operator’s operations manual stated:

When in close proximity to other Company balloons establish contact on UHF Radio... The upper balloon will be responsible for avoiding basket to envelope contact between balloons. The lower balloon will acknowledge calls.

The operations manual also included a Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) instrument, which stated:

Notwithstanding Civil Aviation Regulation (1988) 163;

- Whilst in flight give way to any balloon at a lower level by climbing to avoid the risk of the balloon basket contacting the envelope of the lower balloon, and

- except during inflation and launching, avoid envelope to envelope contact with other balloons.

At the time of the occurrence, CAR 163 had been superseded by the following CASRs:

91.055 - Aircraft not to be operated in a manner that creates a hazard

91.325 - A flight crew member must, during a flight, maintain vigilance, so far as weather conditions permit, to see and avoid other aircraft.

Similar occurrence

ATSB investigation 198900820

On 13 August 1988, two hot air balloons, VH-NMS and VH-WMS, were operating tourist charter flights from the same launch site to the south‑east of Alice Springs Airport. VH-WMS departed about 2 minutes ahead of VH-NMS and climbed to about 4,000 ft AMSL (2,000 ft AGL) and drifted in a westerly direction. After reaching 4,000 ft, VH-WMS then commenced descending as VH-NMS climbed towards it.

VH-NMS continued climbing until its envelope collided with the basket of VH-WMS, tearing a large hole in the fabric. The degree of disruption to the envelope of VH-NMS was such that the balloon could not remain inflated. The balloon then descended uncontrolled until it collided with terrain. The pilot and 12 passengers were fatally injured. VH-WMS landed without further incident.

Safety analysis

During the descent the pilots of both balloons identified the risk of collision. In response to the conflict, the pilot of OOP made 4 radio broadcasts to communicate with the pilot of FSR. However, the pilot of FSR was concentrating on managing the descent and misinterpreted these calls as communications between other balloons and not relevant so did not respond. However, by this time, it was unlikely that action could be taken to avoid the collision.

The pilot of FSR assessed that a collision could not be avoided and knowing the risks of basket to envelope contact, attempted to manage the descent so that the envelopes collided. To assist in avoiding basket to envelope contact, the pilot of OOP attempted to maintain a steady altitude. Although the envelope collision still carried safety risk, these actions resulted in the balloons avoiding basket to envelope contact and neither balloon was damaged in the collision.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition, ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the mid-air collision between Kavanagh E-260, VH-FSR and Kavanagh B-400, VH-OOP on 18 July 2022.

Contributing factors

- After recognising that a collision was likely, the pilot of VH-FSR managed the balloon's descent so that a basket and envelope did not collide, reducing the risk of damage.

Safety actions

Proactive safety action by Red Centre Ballooning

In response to the occurrence, the operator provided education to all company pilots emphasising:

- the need to make radio communications advising of intentions when operating in close proximity if anything out of the ordinary. If required, use alternative means of communication such as mobile phone.

- the importance of passenger communication to the passengers throughout a flight. This could include but is not limited to layover landings and flying around other aircraft.

- that higher balloons should overfly lower balloons before descending as higher balloons are generally travelling faster than lower balloons and may still be carrying some forward momentum after completion of a descent.

- the requirements of the company operations manual, including operating in accordance with the Civil Aviation Safety Authority instrument.

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included the:

- balloon operator

- pilots of the VH-FSR and VH-OOP

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Airservices Australia

- balloon passengers

- Bureau of Meteorology

References

Civil Aviation Safety Authority 2021, Advisory Circular AC 91-14 v1.0 Pilots’ responsibility for collision avoidance, October 2021

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- the balloon operator and the involved pilots

- the Civil Aviation Safety Authority

Submissions were received from:

- the balloon operator and the involved pilots

- the Civil Aviation Safety Authority

The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2023

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] The flight was operated under Civil Aviation Safety Regulations Part 131 (Balloons and hot air airships).

[2] A method of determining winds aloft by tracking the ascent of a small free-lift balloon.

[3] The Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) classifies balloons into three classes. Class 1 – Hot air balloons that have a volume of not more than 260 000 cubic feet. Class 2 – Hot air balloons that have a volume of more than 260 000 cubic feet. Class 3 – Gas balloons.