Executive summary

What happened

On the morning of 3 April 2022, a Bell Helicopter 206L-4, registered VH-PRW, departed with a pilot and passenger on board, for a visual flight rules (VFR) flight from a private property at Majura, Australian Capital Territory to Mangalore, Victoria, with a planned refuelling stop in Tumut, New South Wales (NSW). The helicopter was one of 7 helicopters taking part in a flying tour that morning and the weather forecast indicated low cloud, rain and associated reduced visibility on the planned route.

Two of the 7 helicopters diverted to Wagga Wagga, NSW due to weather while 4 others landed near Wee Jasper, NSW. The pilot of VH-PRW elected to continue until they encountered poor weather conditions and landed the helicopter in the Brindabella region shortly before noon. At 1453 local time, the helicopter departed once again at low level, in overcast conditions with low cloud and light rain. At about 1525, the helicopter commenced a rapid climb and shortly after, entered a steep left descending turn which continued until the helicopter impacted terrain at an elevation of 4,501 ft. A search was initiated the next day with the accident site located later that evening. The helicopter was destroyed, and both occupants were fatally injured.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that, having encountered the forecast low cloud and reduced visibility conditions, the pilot landed the helicopter at an interim landing site. Later that day, the helicopter then departed into cloud and visibility conditions unsuitable for visual flight. It is highly likely these cloud and visibility conditions resulted in the pilot experiencing a loss of visual reference and probably becoming spatially disoriented. This led to a loss of control and an unsurvivable collision with terrain.

Safety message

Weather-related accidents remain one of the most significant causes of fatal accidents in general aviation. The ATSB publication Avoidable Accidents No. 4, Accidents involving Visual Flight Rules Pilots in instrument Meteorological Conditions found that in the decade from 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2019, 101 VFR into IMC occurrences in Australian airspace were reported to the ATSB. Of those, 9 were accidents resulting in 21 fatalities.

In relation to visual flight rules pilots flying into areas of reduced visibility, some key messages to manage risk are:

- Know your limits. VFR pilots should use a ‘personal minimums’ checklist to help control and manage flight risks through identifying risk factors that include marginal weather conditions. Only fly in environments that do not exceed your capabilities. For visual flight at night, ensure you are both current and proficient with disciplined instrument flight.

- Plan ahead. Avoid deteriorating weather by conducting thorough pre-flight planning. Ensure you have alternate plans in case of an unexpected deterioration in the weather and making timely decisions to turn back or divert.

- Don’t press on! Pressing on into instrument meteorological conditions with no instrument rating carries a significant risk of severe spatial disorientation due to powerful and misleading orientation sensations with no visual cues. Disorientation can affect any pilot, no matter what their level of experience.

| Decisions regarding the scope of an investigation are based on many factors, including the level of safety benefit likely to be obtained from an investigation and the associated resources required. For this occurrence, a limited-scope investigation was conducted in order to produce a short investigation report and allow for greater industry awareness of findings that affect safety and potential learning opportunities. |

The occurrence

On the morning of 3 April 2022, a Bell Helicopter 206L-4, registered VH-PRW, was to conduct a visual flight rules[1] (VFR) flight from a private property at Majura, Australian Capital Territory to Mangalore, Victoria with a planned refuelling stop in Tumut, New South Wales (NSW). The helicopter was one of 7 helicopters taking part in a flying tour, following a common itinerary but operating independently.

The weather forecast indicated that the planned route could be affected by low cloud, rain and associated reduced visibility. At about 0900 Eastern Standard Time,[2] two of the helicopters departed Majura. These helicopters encountered low cloud and elected to divert over lower terrain north of the Brindabella Ranges to Wagga Wagga, NSW.

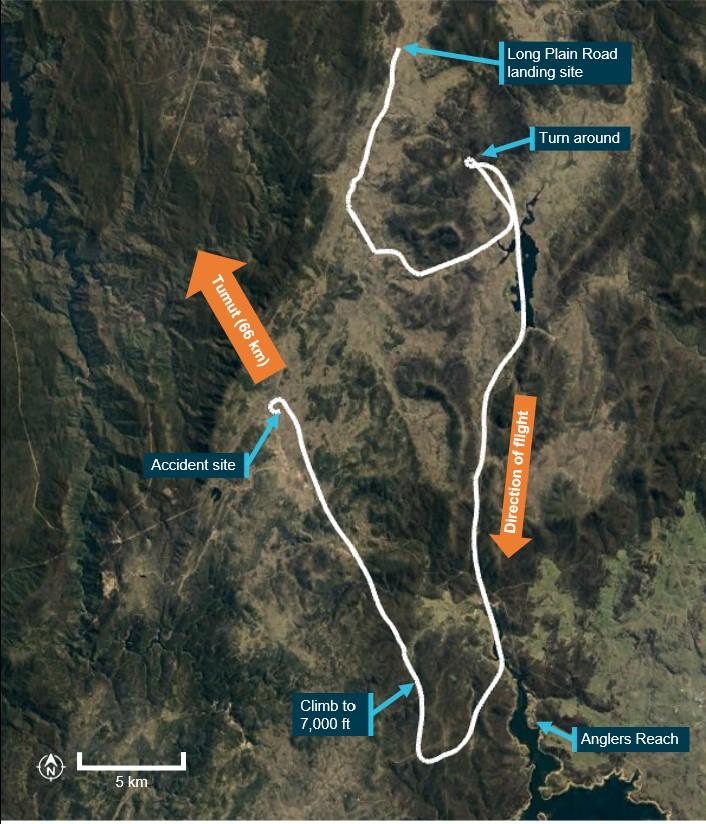

At 1021, VH-PRW, with the pilot and one passenger on board, departed the property at Majura along with the remaining 4 helicopters. Recorded tracking data showed that VH-PRW initially tracked south‑east before turning west toward the Brindabella Ranges (Figure 1). The flight then proceeded south over Corin Dam before heading north to Wee Jasper. As the 5 helicopters approached Wee Jasper, they also encountered deteriorating cloud and visibility conditions. Four of the pilots elected to land on a property near Wee Jasper. The pilot of VH-PRW did not land but continued south to ‘attempt to find a way through to Tumut’.

Figure 1: Flight from Majura to Long Plain

Source: Google Earth and OzRunways, annotated by ATSB

At 1129, the pilot of VH-PRW encountered poor weather conditions and landed the helicopter alongside Long Plain Road in the Brindabella region, outside of mobile phone coverage.

Shortly after the helicopter landed, a passing motorist stopped and approached the helicopter. The pilot advised the motorist that they had landed to wait for better weather conditions before continuing the flight. The motorist arranged to check on the pilot and passenger during the motorist’s return journey later in the day if the helicopter had not already departed by that time.

At about 1230, when VH-PRW did not return to Wee Jasper and the pilot had not contacted other members of the tour, authorities were notified and a search for the helicopter was commenced.

At about 1415, the motorist returned along Long Plain Road and found that the helicopter had not departed. The motorist transported the pilot to a location that enabled phone contact and the pilot contacted the office of the tour organiser to advise of the safe landing. The pilot also stated that they intended to continue the fight following powerlines at about 50 ft above ground level (AGL). The tour organiser advised against this plan and then notified the other members of the tour and authorities of the landing. The motorist and pilot then returned to the helicopter.

Recorded flight tracking data showed that at 1453, the helicopter departed Long Plain Road, with the pilot and passenger on board. Two minutes later, one of the other pilots in the tour noted the helicopter tracking south on a flight tracking application.

Police officers dispatched to locate the helicopter arrived at the landing site just after it became airborne. The motorist and police officers observed the helicopter depart to the south at low level, in overcast conditions with low cloud and light rain. The police officers stated that the helicopter passed ‘at a similar height or slightly above the powerlines’ before being obscured by low cloud.

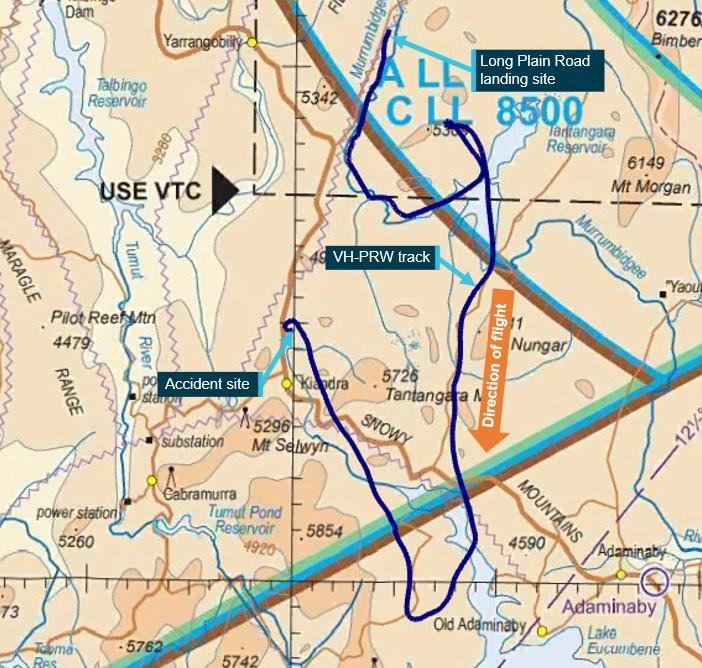

The flight then progressed at heights below 500 ft AGL following geographical features along lower lying terrain (Figure 2). At 1504, the flight turned north-west and took up a track that corresponded with a direct track to Tumut. Two minutes later, the helicopter encountered higher terrain and turned around to head southward, again following lower lying terrain. At 1517, in the vicinity of Anglers Reach, the flight turned north. Two minutes later, the helicopter turned to the north-west, again along a flightpath that corresponded with a direct track to Tumut and commenced a climb to about 7,000 ft above mean sea level (AMSL).

Figure 2: Accident flight

Source: Google Earth and OzRunways, annotated by ATSB

The descending turn continued until the helicopter impacted terrain at an elevation of 4,501 ft at about 1526. The helicopter was destroyed, and both occupants were fatally injured.

On 4 April, in response to the helicopter not re-joining the tour as expected, a second search was initiated. At about 2355, a ground search assisted by helicopter tracking data located the accident site.

Context

Pilot information

The pilot held a valid class 2 medical certificate and a private pilot licence (helicopter).

At the time of the accident, the pilot had about 837 hours of aeronautical experience and did not hold an instrument rating. The pilot’s total flying experience on the Bell 206 was about 532 hours of which about 355 were in the L-4 variant and the remainder in the B-3 variant.

The ATSB found no indicators that increased the risk of the pilot experiencing a level of fatigue known to affect performance.

The post-mortem examination and a review of the pilot’s medical history identified no evidence of a medical event or pre-existing condition that likely contributed to the accident.

Aircraft information

The Bell Helicopter 206L-4 is a 7‑seat, single‑turboshaft engine helicopter equipped with 2-bladed main and tail rotors. VH-PRW was built in 2008 and first registered in Australia in 2016. At the time of the accident, the helicopter had completed about 830 hours in service and was certified for day VFR flight only. The helicopter was fitted with an emergency locator transmitter.

The helicopter was also fitted with the HeliSAS stability augmentation system. This used attitude data and electro-mechanical servo actuators connected to the flight controls rods to apply small corrections to the cyclic as required to maintain a reference attitude. The reference attitude could be set as required by the pilot. The system also incorporated a two-axis (pitch and roll) autopilot.

Tour coordination

The flight from Majura to Mangalore was part of an informal multi-day flying tour involving 7 helicopters. This tour was mostly coordinated by a helicopter operator who provided the itinerary and organised logistic details such as accommodation and fuel availability.

The tour organiser also operated a helicopter flying training and transport operation, but this tour was conducted outside of that operation. The tour organiser held no authority or responsibility for the operation of each involved helicopter, this responsibility was held by each pilot in command.

Terrain

The helicopter departed an interim landing site along Long Plain Road in the Brindabella Ranges. The flight then proceeded over rugged alpine areas of the Snowy Mountains with terrain elevations generally higher than 4,000 ft AMSL. Peaks of 5,854 ft AMSL and 5,726 ft AMSL were located near the final flight track (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Visual navigation chart extract showing terrain in the vicinity of the accident

Source: Airservices Australia and OzRunways, annotated by ATSB

Meteorology

Forecast

The graphical area forecast for the accident region provided a forecast icing level of 10,000 ft AMSL and the following cloud and visibility conditions for the time of the accident (all heights AMSL):

- Generally greater than 10 km visibility with broken[3] cumulus/stratocumulus cloud between 2,500 ft and 10,000 ft.

- Visibility reducing to 4,000 m in scattered rain with broken stratus cloud between 1,500 ft and 6,000 ft. Overlying this, broken altocumulus and altostratus cloud could be expected extending from 6,000 ft to above 10,000 ft.

- Visibility reducing to 3,000 m in scattered rain showers with broken stratus cloud between 1,500 ft and 3,000 ft. Overlying this, broken cumulus and stratocumulus could be expected extending from 3,000 ft to above 10,000 ft.

Photograph

A photograph taken 2 minutes prior to the helicopter departing Long Plain Road showed the cloud conditions at that time (Figure 4). The elevation of the landing site was about 4,429 ft AMSL. The peak of the terrain visible behind the helicopter is 4,573 ft AMSL. This peak was obscured by broken cloud indicating that the cloud base was less than 144 ft AGL.

Figure 4: Cloud conditions 2 minutes prior to departure from interim landing site

Source: motorist via NSW Police Force

Recorded observations

At 1530 (4 minutes after the accident), Bureau of Meteorology weather stations at Cabramurra (14 km south-west of the accident site, elevation 4,864 ft) and Mount Ginini (43 km north‑east of the accident site, elevation 5,774 ft) recorded no rainfall and no separation between the dew point temperature and air temperature. This indicated the presence of very low-level cloud, likely down to ground level at both stations. Neither station was equipped to provide more detailed cloud information.

Visual flight rules

Visual meteorological conditions

The Civil Aviation Safety Regulation (CASR) 91.280 outlined that flight under the visual flight rules (VFR) can only be conducted in visual meteorological conditions (VMC). The criteria are provided in the CASR Part 91 Manual of Standards Table 2.07 (3) and the CASA Visual Flight Rules Guide:

The flight, and the location of the accident, were in Class G (non-controlled) airspace. The following VMC were stipulated for flight under the VFR in Class G airspace when below 10,000 ft and above 3,000 ft or 1,000 ft above ground level (whichever is higher):

- a minimum vertical distance of 1,000 ft and horizontal distance of 1,500 m from cloud

- a flight visibility of 5,000 m.

For helicopter operations in Class G airspace at or below 3,000 ft or 1,000 ft above ground level (whichever is higher), the following minimum conditions were stipulated:

- clear of cloud and in sight of the ground or water

- a flight visibility of 5,000 m or, if operated by day at a speed that allows the pilot to see obstructions or other traffic in sufficient time to avoid collision, 800m.

Minimum height

In addition to minimum visibility and distance from cloud requirements, a pilot is also required to maintain a minimum height above the ground. Unless during take-off, landing or other approved low-flying operation, CASR 91.265 and 91.267 detail that a pilot in command must not fly a helicopter over:

- any city, town, or populous area at a height lower than 1,000 ft above the highest feature or obstacle within a horizontal radius of 300 m of the point on the ground or water immediately below the helicopter; or

- any other area at a height lower than 500 ft above the highest feature or obstacle within a horizontal radius of 300 m of the point on the ground or water immediately below the helicopter.

The investigation identified no evidence to indicate that the pilot intended to undertake an approved low-flying operation.

Recorded data

On-board the helicopter was a mobile device with the OzRunways electronic flight bag application installed. The application had an option for live flight tracking enabled that transmitted the device’s position and altitude. This data was also obtained by the ATSB.

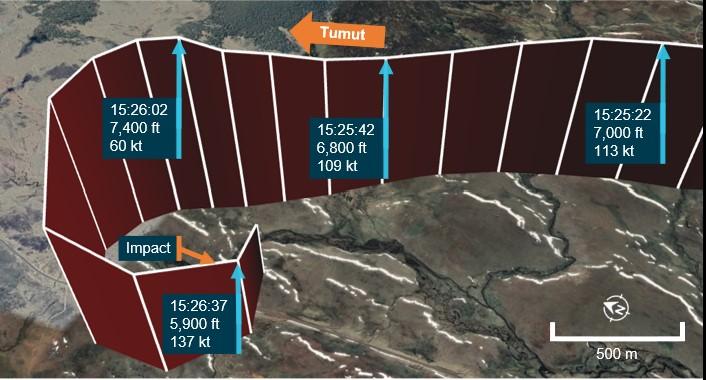

The data showed that at 1519:22 the helicopter turned to a track that corresponded with the direct track to Tumut and 15 seconds later commenced a climb from low level to about 6,600 ft. At 1522:02, a further climb commenced, reaching 7,000 ft at 1522:42. The helicopter continued to track generally toward Tumut at groundspeeds of 105‑115 kt, corresponding to a normal cruise speed for the helicopter. During this segment of the flight, track variations of up to 21° and altitude variations of up to 300 ft were recorded.

At 1525:22, the helicopter descended from 7,000 ft, reaching 6,800 ft about 20 seconds later. From 6,800 ft, a climb was commenced and a further 20 seconds later, the helicopter reached 7,400 ft (at climb rate of 1,800 ft per minute) with a groundspeed of 60 kt. The helicopter then entered a steep left descending turn. During the turn, the groundspeed increased to 137 kt and the descent rate exceeded 3,800 feet per minute (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Aircraft flight path leading up to the accident

Source: Google Earth and OzRunways, annotated by ATSB

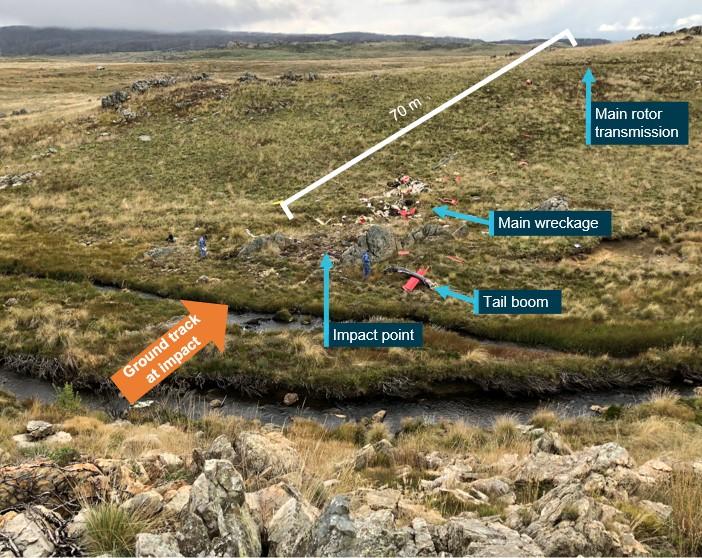

Site and wreckage information

The accident site was located within the Kosciuszko National Park in an area of tussock grass, interspersed by bare protruding rock (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Accident site

Source: ATSB

The helicopter collided with terrain between two rock formations in a descending tight left turn and right side-slip in a northerly direction with a westerly heading. At initial impact, a main rotor blade struck the ground and the tail boom separated. The fuselage then turned left to about a southerly heading. Most of the wreckage was located within 8 m of the impact, but the main transmission, mounts and supporting airframe structure continued a further 70 m up an incline. On-site examination indicated that the engine was providing power at impact. There was no evidence of an in-flight break-up or a pre-existing defect with the drive train or flight controls.

The emergency locator transmitter (ELT)[4] antenna separated from the unit during the impact sequence. The ELT was examined at the ATSB’s technical facilities in Canberra and was found to have activated during the accident. However, the separation of the antenna prevented a signal from being broadcast. While this delayed search and rescue efforts, it did not alter the outcome as the accident was not survivable.

Risks of flying in areas of reduced visual cues

The safety risks of VFR pilots flying from VMC conditions into instrument meteorological conditions[5] are well documented. This has been the focus of numerous ATSB reports and publications, as VFR pilots flying into IMC represents a significant cause of aircraft accidents and fatalities. In 2013, the ATSB Avoidable Accidents series was re-published. Of these publications, the booklet titled Accidents involving pilots in Instrument Meteorological Conditions outlined that:

In the 10 years to July 2019, 101 VFR into IMC occurrences in Australian airspace were reported to the ATSB. Of those, 9 were accidents resulting in 21 fatalities. That is, about 1 in 10 VFR into IMC events result in a fatal outcome.

Spatial disorientation

Spatial disorientation is a type of loss of situation awareness, and is different to geographical disorientation, or incorrectly perceiving the aircraft’s distance or bearing from a fixed location. Spatial disorientation occurs when pilots do not correctly sense their aircraft’s attitude, airspeed, or altitude in relation to the earth’s surface. In terms of an aircraft’s attitude, spatial disorientation is often described simply as the inability to determine ‘which way is up’, although the effects can often be more subtle than implied by that description.

Spatial disorientation occurs when the brain receives conflicting or ambiguous information from the sensory systems. It is likely to happen in conditions in which visual cues are poor or absent, such as in adverse weather or at night. Spatial disorientation presents a danger to pilots, as the resulting confusion can often lead to incorrect control inputs and resultant loss of aircraft control. The flight control sensitivity and relative instability of helicopters compared to aeroplanes increases the risk of such a control loss.

Related occurrences

There have been many accidents relating to VFR pilots flying into reduced visibility conditions. The ATSB publication listed above identifies a number of similar occurrences. Of note is investigation AO-2015-131.

ATSB investigation AO-2015-131

At about 5.30 pm on 7 November 2015, the owner-pilot of an Airbus Helicopters (Eurocopter) EC135 departed Breeza, NSW, on a VFR private flight with two passengers on board to Terrey Hills, NSW.

Witnesses observed the helicopter land in a cleared area in a valley. After 40 minutes on the ground, the pilot, who did not hold an instrument rating and was limited to visual flight operations, departed to the east towards rising terrain in marginal weather conditions. About seven minutes later, and approximately 9 km east of the interim landing site, the helicopter collided with terrain resulting in fatal injuries to all occupants.

The ATSB found that the pilot likely encountered reduced visibility conditions leading to loss of visual reference leading to the collision with terrain.

Safety analysis

While en-route from Majura, Australian Capital Territory, to Tumut, New South Wales, a group of 5 helicopters including a Bell Helicopter 206L-4, registered VH-PRW, encountered deteriorating cloud and visibility conditions. The pilots of 4 of the helicopters landed at Wee Jasper, but the pilot of VH-PRW continued south into the Brindabella Ranges. After encountering further low cloud and poor visibility, the pilot of VH-PRW landed the helicopter alongside Long Plain Road in the ranges.

At 1453, the pilot decided to depart the interim landing site and continue the flight. The flight progressed for 32 minutes until the helicopter commenced a rapid climb and then a descending left turn which continued until the helicopter collided with terrain.

Site and wreckage examination did not identify any defects or anomalies that might have contributed to the accident. Additionally, there was no evidence to support the pilot being incapacitated. Therefore, this analysis will focus on the examination of the factors that led to a visual flight rules (VFR) pilot operating in an area of reduced visibility and losing control of the helicopter.

Departure into unsuitable conditions

Low cloud and poor visibility conditions were forecast across the Brindabella Ranges on the day of the accident. The pilot, having encountered these conditions, landed the helicopter alongside Long Plain Road at 1129. The pilot and passenger then waited for conditions to improve sufficiently to depart the interim landing site.

Despite no such improvement eventuating, after about 3 hours and 24 minutes, the pilot elected to depart and continue to Tumut at about 50 ft above ground level. Photographs, along with police and witness reports, showed that at the time of the departure the cloud and visibility conditions were unsuitable for visual flight. The broken cloud base of less than 144 ft did not allow the pilot to maintain the helicopter both, clear of cloud as required by visual meteorological conditions (VMC) and at the minimum height above terrain of 500 ft.

Departing into unsuitable cloud and visibility conditions, particularly in the vicinity of mountainous terrain at very low level carried significant risk of both losing visual reference and of collision with terrain.

Loss of control

After departing the interim landing site, the flight proceeded at very low level for 26 minutes until the pilot turned the helicopter to a more direct track toward Tumut and climbed to about 7,000 ft above mean sea level (AMSL).

Observations recorded at meteorological stations in the vicinity of the flight indicated that it was highly likely that there was low cloud in the area of the accident. In addition, significant cloud was forecast and observed from ground level to above 10,000 ft AMSL along the flown track. In these conditions it was highly likely that VMC could not be maintained and that reduced visual cues were encountered by the pilot.

Over the next 6 minutes, minor tracking and altitude variations were recorded. It is possible these variations resulted from attempts to manoeuvre around, or in, cloud or rain showers with associated reduced visibility. Additionally, this manoeuvring indicates that the autopilot was not being used during this part of the flight. It could not be determined if the stability augmentation system was being used.

The flight at about 7,000 ft continued until 1525:42 when a rapid climb of about 1,800 ft per minute was commenced. This was immediately followed by a steep descending left turn. This manoeuvring was inconsistent with normal helicopter operation and was indicative of a loss of control.

The pilot did not hold an instrument rating and the helicopter was certified for day visual flight only. This greatly increased the risk of the pilot being affected by special disorientation and it is unlikely the pilot could have maintained control without visual reference for an extended period. Given the forecast and observed conditions, it is likely that during the 6 minutes the helicopter was operating at the higher level, it encountered poor weather. This likely led to the pilot experiencing spatial disorientation which resulted in a loss of control and the collision with terrain.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the collision with terrain involving Bell Helicopter 206L-4, VH-PRW, on 3 April 2022.

Contributing factors

- Having landed the helicopter at an interim landing site due to encountering forecast low cloud and reduced visibility conditions, the pilot subsequently departed into cloud and visibility conditions unsuitable for visual flight.

- It is highly likely that cloud and visibility conditions resulted in the pilot experiencing a loss of visual reference and probably becoming spatially disoriented. This led to a loss of control and an unsurvivable collision with terrain.

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included the:

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- aircraft manufacturer and maintainer

- New South Wales Police Force

- Bureau of Meteorology

- OzRunways

- tour organiser.

References

Australian Transport Safety Bureau, 2019, Avoidable Accidents No. 4 Accidents involving Visual Flight Rules pilots in Instrument Meteorological Conditions, Aviation Research and Analysis publication AR-2011-050.

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- NSW Police Force

- the occupants’ next of kin

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- tour organiser.

Submissions were received from:

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- the passenger’s next of kin

- tour organiser.

The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2022

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] Visual flight rules (VFR): a set of regulations that permit a pilot to operate an aircraft only in weather conditions generally clear enough to allow the pilot to see where the aircraft is going.

[2] Eastern Standard Time (EST): Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) + 10 hours.

[3] Cloud cover: in aviation, cloud cover is reported using words that denote the extent of the cover – ‘scattered’ indicates that cloud is covering between a quarter and a half of the sky, ‘broken’ indicates that more than half to almost all the sky is covered.

[4] Emergency locator transmitter (ELT): a radio beacon that transmits an emergency signal that may include the position of a crashed aircraft, activated either manually or in the crash.

[5] Instrument meteorological conditions (IMC): weather conditions that require pilots to fly primarily by reference to instruments, and therefore under Instrument Flight Rules (IFR), rather than by outside visual reference. Typically, this means flying in cloud or limited visibility.