Executive summary

What happened

On 31 December 2021, a Kavanagh B-350 hot-air balloon, registered VH BSW and operated as a scenic charter flight by Picture This Ballooning (PTB), was being prepared near Glenburn, north of the Yarra Valley, Victoria, with one pilot and 16 passengers. The pilot conducted a pre-flight safety briefing and departed shortly after, intending to land near Yarra Glen.

About 42 minutes into the planned 1‑hour flight, the pilot received a report that the surface wind near the landing area was increasing. The pilot assessed multiple landing options over the next 17 minutes while the wind was increasing. The pilot then made an approach to a landing field and the balloon landed hard with 2 passengers seriously injured.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that the pilot rejected several suitable landing fields to avoid possible post‑landing logistical and operational difficulties. This progressively reduced the safe landing sites available to the pilot.

The field in which the pilot decided to land contained fences not previously known to the pilot, powerlines downwind, and no known landing sites further along the balloon's track. This landing site presented high risks in the prevailing windy conditions.

The landing was complicated by the balloon descending faster than intended, bouncing off the ground back into the air, and then manoeuvres to clear fences. These factors, in combination with the prevailing winds and nearby power lines, led to the pilot descending the balloon rapidly from an excessive height resulting in the hard landing.

The investigation also found that all required actions of the pre-flight passenger safety briefing were not completed, probably due to time pressure and the pilot’s assumption that all passengers would understand an abbreviated briefing. The incomplete briefing probably resulted in 2 passengers adopting a deep squat position during the hard landing, causing their injuries.

The ATSB further identified that the maximum number of passengers that the balloon operator allowed to be carried on the balloon meant that there was insufficient room in the basket for them to adopt the landing position specified in the operator's procedures to reduce the risk of injury.

What has been done as a result

The balloon operator has reduced the maximum number of passengers that the balloon can carry to ensure that all passengers can achieve the required backwards facing landing position. The operator is also reviewing maximum passenger capacities on all of its balloons.

Safety message

This accident demonstrates the importance of passengers adopting the correct body position during landing to reduce the likelihood and severity of injury. The pre-flight briefing is critical in ensuring passenger preparation, particularly as opportunities to reinforce the information during flight may be limited. Pilots should use all available resources (such as, passenger demonstrations and safety briefing cards) to ensure that each passenger understands the landing position and its importance. Further, commercial balloon operators are reminded to ensure that all passengers can physically achieve the required landing positions to reduce the risk of injury.

When faced with deteriorating wind conditions, pilots should prioritise occupant safety in the selection of a landing field. This reduces the risk of a hard landing or accident. Post flight logistical or operational considerations are of secondary importance.

Early on the morning of 31 December 2021, a Kavanagh B-350 hot-air balloon, registered VH‑BSW and operated as a scenic charter flight by Picture This Ballooning (PTB), was being prepared for departure near Glenburn, north of the Yarra Valley, Victoria, with one pilot and 16 passengers. Another balloon of the same operator, and four other balloons from different operators, were also being prepared for take-off at the same location.

At about 0420 Eastern Daylight-saving Time,[1] the pilot of VH-BSW obtained relevant weather information from both the Bureau of Meteorology and another balloon pilot and assessed the conditions as suitable to depart. The pilot intended landing south-east of Yarra Glen (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Balloon flight track

Source: Google Earth, annotated by ATSB

After the passengers had climbed into the basket, the pilot conducted a pre-flight safety briefing and, at 0547, the balloon departed for an anticipated 1-hour flight. Shortly after, the balloon’s ground crew member travelled in a car towards the intended landing area to assist with balloon and passenger retrieval.

The pilot climbed the balloon to a cruise altitude of between 2,500 and 2,700 ft above mean sea level (AMSL), before allowing the balloon to descend into the Yarra Valley to reduce the balloon’s speed. The balloon levelled off at about 200 ft above ground level (AGL) at 0620 and a speed of 15 kt.

At about 0629, the pilot heard the radio broadcast of a ground crew member from another balloon operator that the surface winds were increasing to about 10 kt near the intended landing area. At this time, the pilot started looking for landing sites.

At about 0632, the pilot instructed the passengers to take up landing positions and made an approach to the intended landing area. As the balloon descended, the wind turned the balloon west, away from the site, preventing the landing from being completed. The pilot continued to assess landing options over the next 14 minutes (see the section titled Potential landing sites). During this time, the balloon’s groundspeed varied between 9 and15 kt.

At about 0646, the balloon’s flight continued over a small hill before the pilot instructed the passengers to again get into the landing positions. The pilot intended to float above a seeded field, and land in an adjacent field further along the balloon’s track (Figure 2). Shortly before reaching the seeded field, the pilot pulled the parachute vent line for about 10 seconds to descend for landing (see the section titled Balloon information).

Shortly after, the balloon started descending faster than the pilot anticipated. The pilot operated the burners but was unable to arrest the balloon’s descent and the bottom of the basket contacted the ground. The balloon then started rising so the pilot pulled on its rip line, opening the vent to deflate the balloon (see the section titled Balloon information), intending to touchdown over a nearby fence.

Figure 2: Balloon approach and landing

Only relevant fences have been marked. Source: Google Earth, annotated by ATSB

After the balloon climbed into the air, the pilot noticed another fence running diagonally across the intended landing area along the flight path. The pilot held the rip line to maintain the size of the vent opening, and the balloon continued over this fence, reaching a height of about 40 ft. The pilot then resumed pulling the rip line, opening the vent further and the balloon descended rapidly, landing hard in the field at about 0648. After the basket touched down, it tipped over and was dragged for 30-40 metres along the ground before coming to rest.

The balloon and basket were not damaged during the hard landing, but two passengers sustained serious leg injuries. There was another occurrence reported to the ATSB involving one of the other balloons that had departed Glenburn that morning, but the circumstances of that event were unrelated to the development of this accident.

__________

Balloon information

VH-BSW was a Kavanagh B-350 balloon which included an envelope, double T‑partitioned basket with 32 rope handles (Figure 3) and 4 passenger compartments, a three burner system and 3 propane fuel tanks.

Figure 3: Double-T partitioned basket (example)

The depicted basket has a four-burner system. Source: Kavanagh Balloons

The balloon was equipped with a Lite Vent deflation system. In-flight venting was achieved by pulling on the parachute vent line which in turn pulled the vent panel at the top of the balloon for a controlled release of air. Releasing the vent line allowed the vent panel to close. The parachute vent was used to descend the balloon, such as when approaching to land. For final landing, when the balloon was close to the ground, the rip line was pulled so that the centre of the vent panel was pulled down into the balloon for rapid deflation. The more the rip line is pulled, the larger the vent opening, and the more air allowed to escape through the vent. Releasing the rip line does not close the vent panel.

The balloon’s flight manual included the following information about the rip line:

The centre pull rip line must not be activated if the basket floor is more than 2 metres (six feet) above ground level unless during an emergency landing.

WARNING: Operation of the Lite Vent or Smart Vent centre pull rip line will cause the balloon to empty very quickly and could cause damage and/or injuries if this limitation is ignored.

The balloon was also fitted with rotation vents on the side of the envelope which the pilot could operate to orientate the balloon during flight. These vents were used to ensure that the long side of the basket was perpendicular to the direction of travel during landing.

Pilot information

The pilot held a commercial pilot licence (balloon), with significant balloon piloting experience which included 3,000 hours of flying, of which 300 hours were on the Kavanagh B-350. In the previous 90 days, the pilot had flown 26 hours, including 18 on the B-350.

Meteorological information

Weather considerations

A temperature inversion is a layer of air in which the temperature increases with height, rather than decreasing as is normal. A low-level or surface inversion occurs when the ground cools overnight by radiating heat, also cooling the layer of air closest to the ground. These low-level inversions form a stable layer of air, typically extending a few hundred feet and prevent the higher altitude wind from mixing with the lower level winds near the ground.

An inversion layer can dissipate when the ground is heated by the sun, which allows the higher altitude winds, with relatively higher speed, to mix down towards the earth’s surface. It is for this reason that balloon pilots aim to conduct flights before an inversion layer breaks down and wind conditions deteriorate.

The Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) advisory circular AC 131-02v2.0 Manned free balloons - Operations provided the following guidance on the stability of the atmosphere:

Paragraph 3.2.18. Thermals and atmospheric instability can seriously affect the safety of flight in lighter‑than‑air aircraft. In conditions of higher ambient temperatures, such as can exist in the summer months, pilots should be aware of the possibility that flying conditions may change very quickly as the temperature rises.

Paragraph 3.2.19. Pilots preparing to conduct a flight in higher ambient temperatures, when atmospheric instability may exist during the planned flight or on landing, should access as many local weather information sources and meteorological forecasts as practicable. Pilots should pay attention to any forecast temperature and humidity increases in the forecast period and be prepared to amend the flight plan.

Pre-flight

The pilot recorded the information provided by the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) telephone briefing on the morning of the flight. These included:

- Coldstream temperature observation 12.9 °C (at 0420)

- Surface wind from north-northeast at 5 kt for the expected flying time (0600-0700)

- 2,000 ft wind from north-northwest at 20-25 kt

The pilot also received information from another balloon pilot[2] that the inversion layer would be starting to break down earlier than usual but still after the expected landing time.

The pilot completed a pre-flight load chart, recording a surface temperature of 16 °C and with sufficient lifting capacity available to conduct the flight. The ATSB review of the balloon’s load chart indicated that the lifting capacity for the balloon was sufficient to conduct flights up to 4,000 ft with a surface temperature of up to 23 °C.

Forecast

The Yarra Valley Meteogram[3] showed 100 ft wind from north-northeast at 5 kt for the expected flying time. The F160 model forecast indicated a temperature inversion at about 800 ft AMSL, with wind speeds above the inversion increasing with height (10-30 kt). The inversion was forecast to break down between 0900 and 1100.

Data and observations

The balloon’s GPS unit recorded the balloon’s velocity (and thus wind speed and direction) during the flight. In the final 10 minutes of the flight between 0 and 150 ft AGL, the balloon’s speed varied between 9 and 17 kt.

The pilot described the wind conditions during the latter portion of the flight as ‘gusty’ and that the reason for the unintended touchdown with the ground just before the final landing might have been due to turbulent wind on the leeward side of the small hill the balloon floated over.

Passenger safety briefings

The operator’s Operation’s Manual (OM) and Emergency Procedure’s Manual (EPM) contained the following information on passenger safety briefings:

Passengers are to be briefed on the ballooning experience in general and safety aspects of ballooning (for example, the fan, landing positions, exiting the basket). Pilots should make use of the PTB checklists and briefing cards found on board all PTB balloon baskets.

Brief passengers inside the basket on landing positions before take-off (passengers must practise and demonstrate the landing position)

Assume you will always have a difficult landing so be confident that all passengers can take their landing positions without a further briefing.

Before landing, brief the passengers on the landing procedure.

During emergency landings, advise passengers to expect a hard landing and instruct them into the brace position with knees bent.

Safety briefing cards

Civil Aviation Order 20.11[4] (Emergency and lifesaving equipment and passenger control in emergencies) required that passenger safety information cards be available to passengers on any charter flight with a seating capacity greater than 6. It stated that the cards must be carried in a convenient location and detail the passenger brace position for an emergency landing.

The operator’s OM and EPM manuals outlined that each balloon was to carry a passenger briefing card which was to be mounted inside the basket and available at the meeting point.

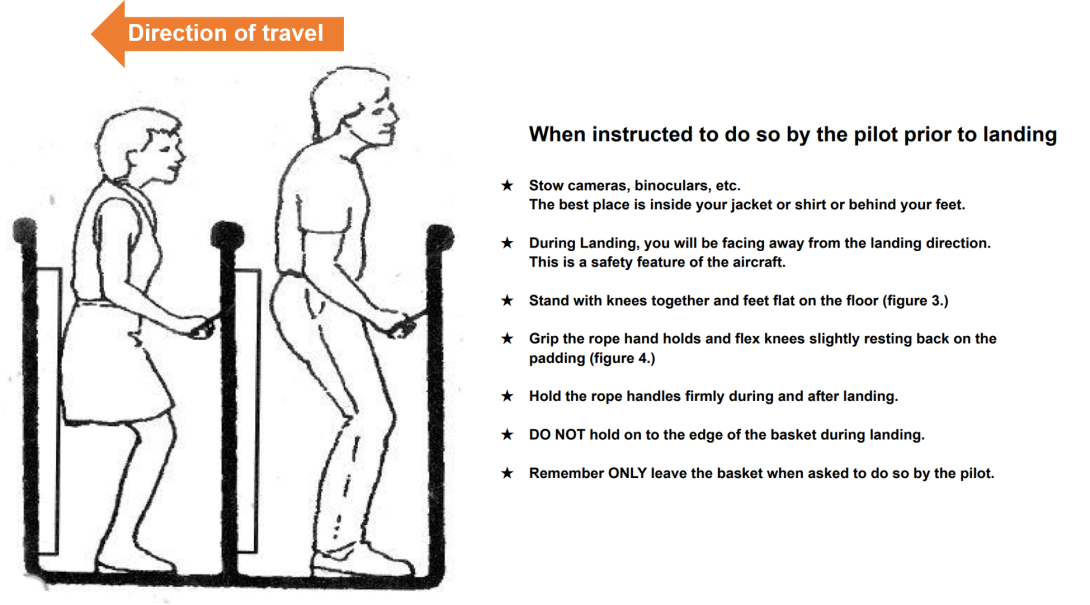

The briefing cards provided information on balloon safety, including landing instructions, and a pictorial representation of the body position to adopt during landing (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Operator safety briefing card

Source: Picture This Ballooning, annotated by ATSB

Pre-flight briefing

Advisory circular AC 131-02v2.0 provided guidance on pre-flight briefings:

Paragraph 4.1.6.2…The safety briefing will usually be conducted by the PIC and should include the following:

an instruction and demonstration of the landing position, appropriate to the balloon design, that a passenger must adopt for landing.

…an instruction to flex the knees on touch down to minimise the effect of any impact during landing.

The pilot reported that a verbal pre-flight briefing about the landing positions was provided to the passengers while they were in the basket and included instructions to hold onto the rope handles, bend the knees, that there might be multiple bounces during the landing, and that the basket might tip over and drag.

The balloon was fitted with a video camera that captured images before and during the flight at 5 second intervals. The images during the pre-flight briefing did not appear to show the passengers demonstrating the landing position, and not all passengers reported being asked to provide the pilot with a physical demonstration. The pilot advised that the passengers were possibly not asked to demonstrate the landing positions as there was some time pressure during take-off due to the forecast weather. The pilot also assumed that verbal instructions for the passengers on‑board (all reported to be English speaking) would be sufficient to understand the landing positions. The two passengers injured during the hard landing reported that the briefing felt rushed without a lot of emphasis on the landing position.

The passengers were not asked to review the safety briefing cards before or during the flight. The pilot reported not using the cards during recent pre-flight briefings because the passengers on these flights had primarily been English speaking and the pilot believed that the briefing cards were only effective with non-English speaking passengers.

Pre-landing briefing

Advisory circular AC 131-02v2.0 provided guidance on pre-landing briefings:

Paragraph 4.1.6.5. On final approach to landing the PIC should ensure all passengers are comfortable in the landing position and be prepared to correct any anomalies before touch-down.

During the pre-landing briefing, the pilot:

- instructed passengers to adopt the landing positions during the approach

- visually checked that the passengers were in the landing positions

- re-iterated at appropriate times to stay in the landing positions

- warned that there was going to be a hard landing.

Most passengers recalled being verbally instructed to adopt the landing positions and after the initial bounce, being told to brace for a hard landing. Both passengers that were subsequently injured interpreted the hard landing instruction to mean they needed to crouch down deep into the basket and brace.

Landing positions

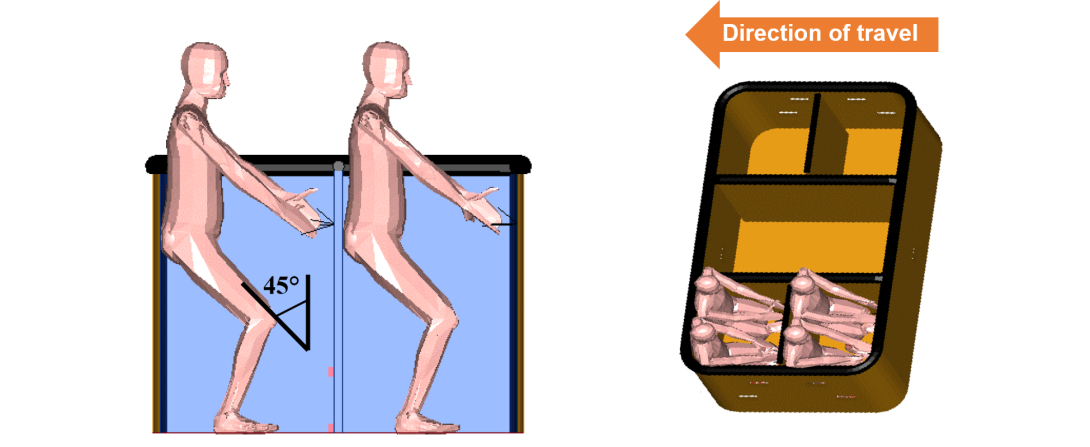

The landing position on the operator’s safety briefing cards was a similar position to that recommended by the United Kingdom Civil Aviation Authority (CAA)[5] for the double T-partitioned basket and required a passenger’s back to be facing the direction of travel with knees bent at an angle of less than 90 degrees (Figure 5). The research conducted to support the CAA recommendation[6] found the backwards facing landing position reduced the risk of injury compared to the sideways facing position (Figure 6) during heavy and tip-over landings.[7]

Figure 5: Recommended landing position (double T-partitioned basket)

Source: United Kingdom Civil Aviation Authority, annotated by ATSB

Figure 6: Sideways landing position (double T-partitioned basket)

Source: United Kingdom Civil Aviation Authority, annotated by ATSB

Flight camera images showed the passengers facing sideways during the pre-flight briefing, and before the initial touchdown. Just before this touchdown, the two passengers that were subsequently injured lowered themselves further into the basket than the other passengers who remained more upright. The long side of the basket was orientated perpendicular to the direction of flight during the initial touchdown as shown (Figure 6). After the first touchdown, the two injured passengers, and another one, lowered themselves further into the basket, probably crouching in a deep squat position with the knees bent more than 90 degrees. They remained in those positions during the final landing.

The basket contained internal padding to support passengers’ backs during landing but did not extend all the way to the basket floor. One of the injured passengers reported that one foot slid under the padding during the hard landing and possibly contributed to the injury.

The Australian Ballooning Federation Pilot Training Manual stated that a descent rate greater than 400 feet per minute on landing could cause personal injury and damage the equipment. The ATSB determined that during the final landing the average descent rate was at least 470 feet per minute. Just before the balloon landed, the balloon had turned such that the long edge of the basket was orientated about 50° from the direction of travel (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Basket orientation during final landing

Source: United Kingdom Civil Aviation Authority, annotated by ATSB

Number of passengers

The balloon’s flight manual included the following passenger limitations:

Partitioned baskets are limited to a maximum of 6 people per passenger compartment and 2 flight crew in the pilot compartment.

All occupants must have access to a minimum of one hand hold eg: rope handle or tank rim.

All occupants must have reasonable space to achieve a safe landing position and reasonable comfort levels during the flight.

The operator’s OM included information on the maximum ‘passenger seats’ available for each balloon within the fleet. The passenger capacity for VH-BSW was 17. The operator advised that the following factors were used when determining the maximum passenger capacity:

- maximum total passenger weight for each balloon envelope based on its condition.

- number of rope handles – minimum of 2 handles per passenger

- flight manual considerations

The camera images showed that there were 4 passengers located in each passenger compartment, and review of the passenger load charts were all within balloon weight limitations.

The pilot stated that the passengers were instructed into sideways facing landing positions during the pre-flight briefing because the number of passengers on board meant that they physically could not adopt a backwards facing position. A review of the camera images confirmed that it was unlikely that all passengers could have physically achieved a backwards facing landing position. The images and passenger weights indicated that some passengers were of above average size, and some below average, so combined represented a typical group of passengers.

The pilot reported instructing passengers into the backwards facing position for previous flights on VH-BSW as there were less passengers and enough space for them to achieve this position.

Balloon landing considerations

The United States’ FAA Balloon Flying Handbook, Chapter 8 – Landing and Recovery provided the following advice on landing considerations:

When selecting a landing site, three considerations in order of importance are: safety of passengers, as well as persons and property on the ground; landowner relations; and ease of recovery.

The best landing site is one that is bigger than the balloon needs and has alternatives. If the balloon has three prospective sites in front of it, the pilot should aim for the one in the middle in case the surface wind estimate was off. If the balloon has multiple prospective landing sites in a row along its path, the pilot should take the first one and save the others for a miscalculation. Unless there is a 180° turn available, all the landing sites behind are lost.

When faced with a high wind landing, the balloon pilot must remember that the distance covered during the balloon’s reaction time is markedly increased… A pilot who is not situationally aware and fails to recognize hazards and obstacles at an increased distance may be placed in a dangerous situation with rapidly dwindling options.

The balloon’s flight manual also stated the following regarding the approach to land:

A suitably large landing site should be selected, free of obstacles such as power lines, buildings and livestock. The overshoot area (downwind of the landing) should be free from high obstacles where possible in case the landing has to be aborted.

When a fast landing is anticipated extra space will be required for the potential drag and deflation of the balloon and a low approach should be favoured to minimise the vertical speed during landing.

Landowner relationships

Much of the land within the Yarra Valley suitable for hot air balloon use was privately owned, potentially containing the source of the livelihood of the landowners (for example, livestock and crops). In order to avoid problems such as trespassing, commercial balloon operators developed good relationships with landowners to permit take-offs, landings, and recovery of passengers and equipment from their properties. Some properties were approved for landing while others were not. Balloon pilots generally avoid landing in fields with livestock and crops to maintain good landowner relationships.

Information on maintaining positive landowner relationships was contained in the operator’s OM:

Good landowner/farmer relationships are imperative for the continued operation of Picture This Ballooning.

Maintain a map marked with the landing sites wherein the owner has given approval where practicable.

Select a landing field that should cause the least possible inconvenience to the landowner.

The pilot stated that in an emergency, the primary concern was the safety of passengers, and a landing could be made at any place considered practical – even if this occurred on a property not approved by a landowner. If there was no emergency, landing a balloon on a crop or a non‑approved property could create problems for future balloon operations.

Potential landing sites

The pilot acknowledged that apart from the final landing location, there were other potentially suitable landing sites along the balloon’s path but did not consider that the wind conditions warranted an attempt to land in these fields. These sites were rejected as one had cattle, another had locked gates that would have posed logistical problems with passengers and balloon retrieval, while others had been seeded for crops (Figure 8). These fields were longer than the final landing site and had no power lines nearby.

The pilot also stated that the final landing field was the last known landing site along the balloon’s path, and that beyond this, the potential landing fields were smaller. A review of the flight track indicated that built up suburban areas were about 3 km further along the flight path from the balloon’s final landing location.

Figure 8: Flight track with potential landing sites

Source: Google Earth, annotated by ATSB

Power lines

The Australian Ballooning Federation ABF Pilot Training Manual, Part 5 – Aerostatics and Airmanship included the following information regarding power lines:

Contact with power lines should be very carefully avoided. Any voltage can cause fatal or very serious injuries.

IF IN DOUBT, RIP OUT. If there is any doubt about your ability to clear the wires, make an emergency landing without hesitation. Pull the ripline as you warn passengers to hold on for landing, and turn off pilot lights and vent fuel hoses if there is time. There is considerably less risk of injury, fire and electrocution if the envelope contacts the wires than if the basket does.

The pilot was aware of the location of power lines downwind of the final landing field before committing to land in that field. The pilot stated that although using the parachute vent was standard procedure during an approach to land, its use during the final landing sequence might not have descended the balloon fast enough to avoid contacting the power lines. Further, attempting to ascend over the lines would be dangerous given the balloon’s distance and height from the lines. The pilot considered that the immediate use of the rip line was necessary to avoid contacting the power lines.

Similar occurrences

ATSB Investigation AO-2011-045

On 2 April 2011, during a scenic charter flight and while operating at low level, the pilot of a Kavanagh Balloons E‑210 hot-air balloon, registered VH-OTZ, was unable to arrest the balloon's descent and initiate a climb in time to avoid powerlines, requiring an emergency descent and landing. The balloon landed hard in a paddock with the basket not orientated correctly to the direction of flight. It bounced, dragged and inverted along a distance of 60 m, resulting in injuries to the occupants and minor damage to the basket.

ATSB investigation AO-2018-016

On 8 February 2018, a Kavanagh Balloons B-350, registered VH-EUA, departed Glenburn, Victoria for a scenic charter flight with a pilot and 15 passengers on board. About 45 minutes into the flight, over the Yarra Valley, the balloon experienced a sudden wind change with associated turbulence. The pilot decided to land immediately resulting in a hard and fast landing. Eleven passengers were injured, 4 of them seriously.

Although some passengers were provided with a safety briefing prior to boarding the balloon, the operator’s normal safety briefing for passenger’s post boarding was not conducted. In addition, the briefing prior to boarding was not effective in ensuring all passengers understood the required landing position to use for an emergency landing. The ATSB identified a safety issue with the operator’s risk controls which did not provide assurance that all passengers would understand the required procedures for emergency landings.

__________

- That balloon pilot had reportedly received this weather information from the BoM.

- The BoM had not retained a copy of the Yarra Valley Meteogram available on the morning of the flight. However, a Meteogram was generated for the investigation using archived weather data.

- Civil Aviation Safety Regulation Part 131 was released on 2 December 2021. However, because the Part 131 Manual of Standards was deferred, CAO 95.53 was still effective at the time of the accident which included the requirement to comply with CAO 20.11.

- United Kingdom Civil Aviation Authority (2007), Balloon Notice 1/2007, Passenger Landing Position Guidance to Operators, available from the UK CAA website

- United Kingdom Civil Aviation Authority (2006), CAA Paper No. 2006/06, Evaluation of and Possible Improvements to Current Methods for Protecting Hot-Air Balloon Passengers During Landings, available from the UK CAA website.

- When an obstacle is hit in the double T-partitioned basket, the backwards landing position was found to increase the risk of injury when compared to the sideways facing position. However, heavy and tip-over landings were found to be more common, so the backwards facing position was considered the overall safest position to adopt. A heavy landing was defined as having a horizontal speed of 10 kt and descent rate of 500 feet per minute. A tip-over landing was defined as having a horizontal speed of 10 kt and descent rate of 300 feet per minute.

On 31 December 2021, a Kavanagh B-350 hot-air balloon, registered VH BSW and operated as a scenic charter flight by Picture This Ballooning (PTB), was being prepared near Glenburn, north of the Yarra Valley, Victoria, with one pilot and 16 passengers. The pilot conducted a pre-flight safety briefing and departed shortly after, intending to land near Yarra Glen.

About 42 minutes into the planned 1‑hour flight, the pilot received a report that the surface wind near the landing area was increasing. The pilot assessed multiple landing options over the next 17 minutes while the wind was increasing. The pilot then made an approach to a landing field and the balloon landed hard with 2 passengers seriously injured.

Landing areas

The forecast weather indicated that the conditions were suitable for the flight. However, after descending into the valley, the balloon’s relatively high speed at low level indicated that the inversion layer had started to break down earlier than forecast. Despite this, the wind conditions were still suitable to conduct a safe landing.

Since the wind conditions would probably degrade further, it would have been prudent for the pilot to select a large field with minimal obstacles and alternative landing sites nearby as a backup. However, the pilot rejected several large landing sites to avoid probable logistical difficulties with passenger and balloon retrieval or perceived negative impact on future operator-landowner relationships, which progressively reduced the number of safe landing sites available. Rejecting these landing sites, particularly the last two large seeded fields, in favour of a relatively small field with fences, power lines downwind, and no known alternate sites, increased the risk of obstacle collision and a hard landing in the prevailing wind conditions.

Hard landing

The final approach to land was initially complicated by the balloon descending faster than intended and touching down unintentionally in a seeded field before rising back into the air. Whether this descent was from excessive use of the parachute vent during the approach, insufficient burner application, the turbulent wind on the leeward side of the small hill, or a combination of all three, could not be determined.

The burner application to arrest the initial descent would have slowed the vertical descent rate, which was desirable, but also filled the balloon with hot air, increasing the rate of ascent after the touchdown and risk of contacting the power lines. After the balloon rose back into the air, the normal landing procedure was to use the parachute vent, and then pull the rip line when the balloon was close to the ground. However, the pilot started pulling immediately on the rip line to quickly descend the balloon and avoid the power lines. Although different to standard procedure, the use of the rip line was reasonable in the situation, but reduced control of the balloon’s final rate of descent.

Further complicating the situation was the late identification of a fence during the approach. This fence needed to be manoeuvred over and probably contributed to an increase in the maximum height that the balloon reached after the first touchdown. With the relatively high wind conditions and the distance to the powerlines reducing, the pilot pulled the rip line further resulting in the rapid descent and hard landing. While undesirable, the hard landing was the safer option instead of risking contact with the power lines.

During the final landing sequence, the balloon turned so that the long side of the basket was not orientated optimally, ideally with the direction of flight, possibly due to the wind or rapid loss of air through the vent. This orientation during the hard landing probably reduced the effectiveness of the handholds and landing position in preventing passenger movement, increasing the risk of injury. Further, although the pilot might have visually checked the passenger positions during the initial approach to land, it is unlikely the pilot re-checked their positions after the initial balloon touchdown. While rechecking passenger positions and orientating the basket correctly would have reduced the risk of injury, there was little time available, and the pilot was focussed on the more important task of controlling the balloon to avoid hazardous obstacles.

Pre-flight briefing

On every balloon flight, passengers need to adopt a specific body position during landing to reduce the likelihood and severity of injury. There are limited opportunities for a pilot to demonstrate or reinforce this briefing during flight so passenger preparation during the pre-flight briefing is critical. Although the pilot provided a verbal briefing of the landing position to the passengers before the flight, the required passenger landing position demonstration and use of briefing cards were omitted. The pilot probably missed these important steps because of time pressure and an incorrect assumption that all passengers would fully understand a verbal briefing.

This incomplete briefing reduced the likelihood of all passengers understanding the landing position, and probably resulted in some passengers not adopting the instructed body position during the hard landing, resulting in injuries to 2 passengers who adopted a deep squat position.

Passenger landing positions

Being able to achieve a safe landing position is an important consideration for every flight. Although the passengers:

- represented a typical group of adult passengers

- had sufficient handholds

- were within the balloon’s weight limitations

- were within the operator maximum passenger limits

the operator’s required safe landing positions (backwards facing) could not be physically achieved by all the passengers. Consequently, during the pre-flight briefing, the pilot instructed all the passengers to take a sideways facing landing position. This positioning in that type of basket increased the risk of injury during landing. However, since all the passengers were in a sideways facing position during the hard landing without any reported injuries, except for the 2 passengers injured who were also crouching down in a deep squat position, it is unlikely that the sideways facing position contributed to their injuries.

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. Safety issues are highlighted in bold to emphasise their importance. A safety issue is a safety factor that (a) can reasonably be regarded as having the potential to adversely affect the safety of future operations, and (b) is a characteristic of an organisation or a system, rather than a characteristic of a specific individual, or characteristic of an operating environment at a specific point in time. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the hard landing involving Kavanagh Balloons B-350, VH BSW, 2 km south of Lilydale Airport, Victoria on 31 December 2021.

Contributing factors

- The pilot rejected several suitable landing fields to avoid possible post-landing logistical and operational difficulties. This progressively reduced the safe landing sites available to the pilot.

- The field in which the pilot decided to land contained fences not previously known to the pilot, powerlines downwind, and no known landing sites further along the balloon's track. This landing site presented high risks in the prevailing windy conditions.

- The landing was complicated by the balloon descending faster than intended, bouncing off the ground back into the air, and then manoeuvres to clear fences. This, in combination with the prevailing winds and nearby power lines, led to the pilot descending the balloon rapidly from an excessive height resulting in the hard landing.

- All required actions of the pre-flight passenger safety briefing were not completed, probably due to time pressure and the pilot’s assumption that all passengers would understand an abbreviated briefing. The incomplete briefing probably resulted in 2 passengers adopting a deep squat position during the hard landing, causing their injuries.

Other factors that increased risk

- The balloon landed hard with the basket not orientated optimally to the direction of flight, increasing the risk of injury.

- The maximum number of passengers that the balloon operator allowed to be carried meant that there was insufficient room in the basket for them to adopt the landing position specified in the operator's procedures to reduce the risk of injury. (Safety issue)

|

Central to the ATSB’s investigation of transport safety matters is the early identification of safety issues. The ATSB expects relevant organisations will address all safety issues an investigation identifies. Depending on the level of risk of a safety issue, the extent of corrective action taken by the relevant organisation(s), or the desirability of directing a broad safety message to the aviation industry, the ATSB may issue a formal safety recommendation or safety advisory notice as part of the final report. All of the directly involved parties were provided with a draft report and invited to provide submissions. As part of that process, each organisation was asked to communicate what safety actions, if any, they had carried out or were planning to carry out in relation to each safety issue relevant to their organisation. Descriptions of each safety issue, and any associated safety recommendations, are detailed below. Click the link to read the full safety issue description, including the issue status and any safety action/s taken. Safety issues and actions are updated on this website when safety issue owners provide further information concerning the implementation of safety action. |

Passenger brace positions

Safety issue number: AO-2022-003-SI-01

Safety issue description: The maximum number of passengers that the balloon operator allowed to be carried meant that there was insufficient room in the basket for them to adopt the landing position specified in the operator's procedures to reduce the risk of injury.

AGL Above Ground Level

AMSL Above Mean Sea Level

BoM Bureau of Meteorology

CAA Civil Aviation Authority (United Kingdom)

CASA Civil Aviation Safety Authority

EM Emergency Procedure’s Manual

GPS Global Positioning System

OM Operation’s Manual

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included the:

- pilot

- passengers

- Picture This Ballooning (the operator)

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Bureau of Meteorology

- video images from the accident flight

- recorded data from the GPS unit on the aircraft.

References

ABF (Australian Ballooning Federation) (2019), ABF Pilot Training Manual, ABF

FAA (Federal Aviation Administration) (2008), Balloon Flying Handbook, FAA-H-8083-11A, FAA

CAA (Civil Aviation Authority) (2006), Evaluation of and Possible Improvements to Current Methods for Protecting Hot-Air Balloon Passengers During Landings, CAA Paper No. 2006/06, CAA United Kingdom

CAA (Civil Aviation Authority) (2007), Passenger Landing Position Guidance to Operators, Balloon Notice 1/2007, CAA United Kingdom

CASA (Civil Aviation Safety Authority), (2021), Manned free balloons – Operations, Advisory Circular AC 131-02v2.0, CASA

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- pilot

- Picture This Ballooning (the operator)

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Australian Ballooning Federation

- the injured passengers.

Submissions were received from:

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- the injured passengers.

The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2022

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |