Executive summary

What happened

At 0528 on 20 November 2021, a De Havilland Canada DHC-8, registered VH‑QQD, departed on a charter flight from Perth to Port Hedland, Western Australia.

As the aircraft approached 10,000 ft, the flight crew carried out transition altitude checklist items and observed that the cabin had not pressurised. The flight crew decided to return to Perth and the aircraft landed uneventfully.

What the ATSB found

The aircraft had been undergoing maintenance on the day prior to the occurrence, and for operational reasons the recirculation fan had been removed for fitment to another aircraft. VH‑QQD had not been removed from the schedule as the assigned aircraft for the flight, and its unserviceability was not detected prior to flight. The absence of the recirculation fan on the occurrence flight prevented the aircraft from pressurising.

The operator’s operations department incorrectly interpreted a message from its engineering department regarding the serviceability status of VH‑QQD, and it remained assigned to the charter flight. This allocation remained on the flight crew’s roster and the flight manifest, which contributed to the flight crew’s confidence that the aircraft was serviceable.

As there were no allowable defects against the aircraft, the captain did not check the maintenance log prior to flight and, as a result, did not detect that the recirculation fan had been removed. However, during pre-flight activities the captain observed the circuit breaker that had been opened to facilitate the recirculation fan removal. The captain reset the circuit breaker without reviewing the maintenance log for recent or open defects as per the operator’s flight crew operating manual.

What has been done as a result

After the occurrence, the operator took the following actions:

- refined the terminology used by engineering to communicate aircraft serviceability, and reviewed internal communication methods

- distributed an internal memo to all staff advising that if the aircraft technical logs were not located in the crew room when receiving the aircraft, it was to be considered unserviceable

- distributed an internal memo to flight crews to reiterate existing paperwork and circuit breaker resetting requirements

- incorporated a dedicated compartment for each aircraft’s documents in the crew room with a placard instructing flight crews to contact maintenance watch if the scheduled aircraft’s documents were not in their compartment.

Safety message

Any task, including those that may seem innocuous, should be performed as though it is the last defence to ensure safe operation. The aircraft documents contain the only reliable records of airworthiness that a pilot should trust, and this occurrence shows that thoroughly checking them remains an important control to determine if the aircraft can be operated.

The investigation

| Decisions regarding the scope of an investigation are based on many factors, including the level of safety benefit likely to be obtained from an investigation and the associated resources required. For this occurrence, a limited-scope investigation was conducted in order to produce a short investigation report and allow for greater industry awareness of findings that affect safety and potential learning opportunities. |

The occurrence

Aircraft assignment to the flight

On 15 November 2021, Maroomba Airlines received a request to carry out a charter flight from Perth Airport to Port Hedland Airport, Western Australia, scheduled to depart at 0600 on 20 November 2021. The flight was entered into the operator’s operations management system (AvSys[1]), with an assigned aircraft (VH‑QQD, a De Havilland Canada DHC-8) along with an assigned flight crew. The flight and assigned aircraft information was then added to the crew’s roster.

VH‑QQD was operated on a scheduled flight on Friday 19 November 2021. After the flight, at about 1500, that flight crew made an entry in the maintenance log regarding a propeller de-ice defect, which made the aircraft unserviceable.

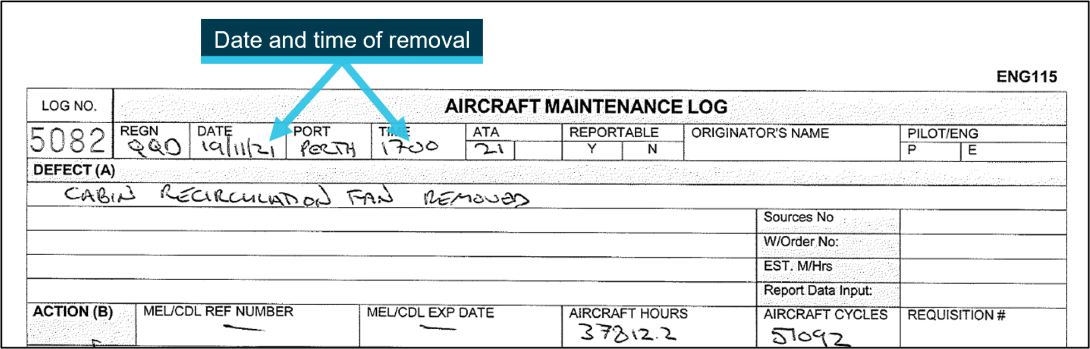

Another of the operator’s 4 DHC-8s, VH‑QQK, was reaching the end of the period it could operate with a permissible unserviceability[2] for its recirculation fan. As the operator did not have engineering personnel rostered on evenings or weekends, it was decided to use the fan from VH‑QQD and leave VH‑QQD unserviceable. The removal of the recirculation fan from VH‑QQD was entered into its maintenance log at 1700 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Aircraft maintenance log entry for recirculation fan removal

Source: Maroomba Airlines, modified by the ATSB

Meanwhile, at 1625, the departure time for the Port Hedland charter flight on 20 November was changed in AvSys to 0500, and the assigned flight crew were made aware.

At 1812 on 19 November, the operator’s duty engineering supervisor used an instant messaging program to communicate the following message about fleet status in accordance with normal protocols:

QQD and QQP in maintenance. AEP, QQK, CWO, NYA Serviceable. QQK MEL [minimum equipment list] 21-10 cleared. Recirc fan serviceable

This message was promulgated to a group that included the operations department. A member of the operations department acknowledged receipt of the status message and updated AvSys. For reasons that could not be determined, the status of VH‑QQD was not updated, and VH‑QQD remained the assigned aircraft for the charter flight on the following morning.

Pre-flight preparation

The operator’s facilities at Perth Airport consisted of a maintenance hangar, an administration and operations building, and an apron area. On 20 November 2021, the captain arrived at 0330 and logged onto AvSys. After confirming the aircraft assigned to the charter was VH‑QQD, the captain saw that the aircraft was positioned on the operator’s apron area, close to the terminal.

The operator's flight crew operating manual required the flight crew to check aircraft documentation when accepting the aircraft. The operator stated that this meant that each document needed to be checked. The manual did not assign this responsibility to either flight crew member in particular.

The captain found that the aircraft documents (see Aircraft documentation suite) for VH‑QQD were not in the crew room as they normally would be for flight crews to review prior to accepting an aircraft. The captain checked the aircraft’s registration on the flight manifest, reconfirming the flight had been assigned to VH‑QQD.

The captain recalled that on a previous occasion prior to flight, the operator’s engineers had not placed the aircraft documents in the crew room after completing maintenance, unintentionally leaving them in the adjacent hangar. As a result, on the present occasion, the captain entered the hangar and located VH‑QQD’s documents on a workbench.

The captain stated that the presence of a pink duplicate maintenance log page, indicating permissible unserviceabilities, would normally prompt them to examine the maintenance log. On this occasion, there were no permissible unserviceabilities, and the captain left the maintenance log in its sleeve. At that time, the maintenance log contained the open entries that made the aircraft unserviceable (that is, the propeller de-ice defect and the absence of the recirculation fan).

The operator required flight and cabin crew members to arrive 1 hour prior to their flight’s scheduled departure time (which was now 0500). The first officer arrived shortly before 0400, while the captain was in the hangar. However, although the assigned cabin crew member had acknowledged the departure time change, they mistakenly thought the flight was scheduled to depart at 0600, in part because the automated rostering system had not updated correctly. At 0415, in an attempt to maintain schedule since the cabin crew member had not yet arrived, the captain and first officer carried out some of the cabin crew’s pre-flight tasks, such as security checks and stowage of catering.

From about 0430, the captain and first officer continued the flight crew pre-flight tasks. To facilitate the removal of the recirculation fan the previous day, engineers had opened its relevant circuit breaker (see Aircraft circuit breakers). The captain re-set it, believing that (based on their knowledge of the system) the circuit breaker had tripped.

At 0440, the flight crew called the fuel provider to find out when they would arrive to refuel the aircraft (the flight crew expected an earlier refuelling, having advised the fuel provider of the flight’s requirements at 0410). Refuelling commenced at 0445 and was completed just before 0500. The cabin crew member arrived at 0500. The 7 passengers boarded the aircraft and taxi commenced at 0519.

Occurrence flight

The aircraft took-off at 0528, just after sunrise, and both pilots later reported that there was significant glare at this time. Additionally, the captain reported the flight crew workload during the departure was high due to the aircraft’s high rate of climb, radio calls, and radar vectoring[3] from air traffic control (ATC). The absence of the recirculation fan prevented the aircraft from pressurising; however, this would not have been known to the crew at the time.

At 0534, as the aircraft approached 10,000 ft and continued to climb, the flight crew carried out transition altitude checklist items. They observed the cabin differential pressure (the difference in pressure between inside the aircraft cabin and the local external atmosphere) to be 0 pounds per square inch (psi), indicating that the cabin had not pressurised. They observed the cabin altitude to be approaching 10,000 ft.

There were no cabin altitude warnings, and the flight crew did not consider it necessary to use supplementary oxygen. Generally, aircraft can operate up to 10,000 ft without the occupants requiring the use of supplementary oxygen or the aircraft being pressurised.

The captain selected the autopilot to altitude hold and requested descent to 10,000 ft from ATC. Once clearance was received, the flight crew commenced descent. The crew carried out the cabin pressurisation failure checklist, but the cabin pressure and altitude indications showed that the aircraft remained unpressurised.

After confirming the relevant circuit breaker was correctly set, the flight crew decided to return to Perth. The cabin crew member was briefed on the nature of the defect and instructed to prepare the cabin for a normal landing. The aircraft returned to Perth and landed uneventfully. The crew and passengers were assigned another aircraft for the flight to Port Hedland.

Context

Aircraft documentation suite

The Maroomba Airlines aircraft documentation suite consisted of a:

- flight log – a history of the aircraft’s flights

- maintenance release – the controlling document that released the aircraft for service, valid for a set period

- maintenance due list – maintenance requirements that were due to be carried out during the maintenance release period

- maintenance log – a history of the aircraft’s maintenance activity and certification (engineers made entries in the maintenance log to record the maintenance requirement, as well as a second entry to detail the work carried out and to certify it had been complete)

- summary of deferred defects card – a list of permissible unserviceabilities.

The maintenance release, maintenance due list, and deferred defects card were individual sheets. The flight and maintenance logs were books. All were typically stored in a folder with an internal sleeve for the maintenance log. Engineers would normally record maintenance activities in the maintenance log only. For the aircraft to be airworthy, all of the documents needed to be actioned appropriately; that is, the maintenance release could be current (as it was in this case) but the aircraft could not be operated on the basis of entries in the maintenance log.

For flights departing from Perth Airport, all the aircraft document folders were normally placed in the crew room prior to flight crew arrival, and then carried on board the aircraft. Prior to accepting an aircraft, the flight crew operating manual required the flight crew to review them to ensure that:

- the aircraft was airworthy

- the flight could be conducted without any scheduled maintenance falling due

- the flight crew were aware of any operational limitations arising from permissible unserviceabilities.

The captain previously flew for a high-capacity airline that kept most aircraft documentation in a single book, and maintenance history or open defects were visible concurrently with the flight log. They had recently been trained and checked to line as a direct entry captain on the operator’s DHC‑8 fleet. The captain recalled that during this training it ‘wasn’t normal procedure’ to review the recent maintenance history.

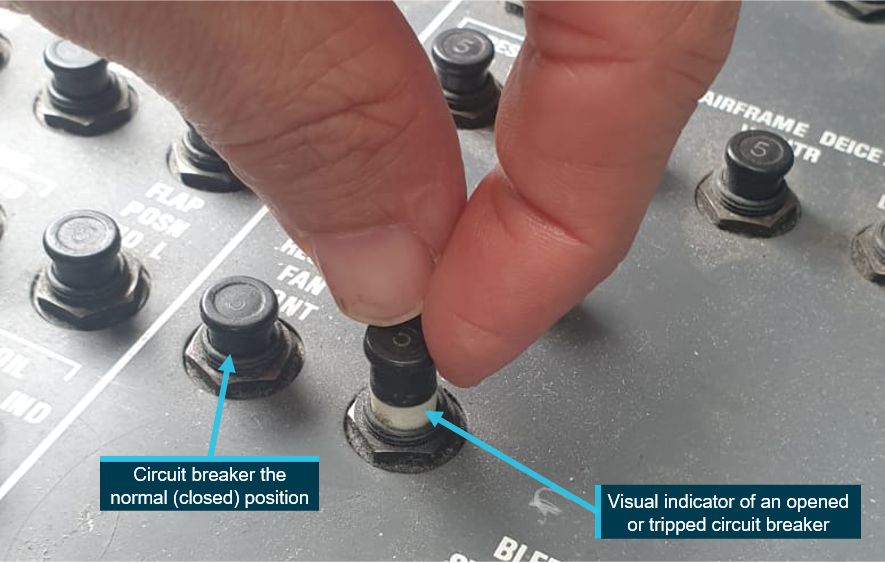

Aircraft circuit breakers

An aircraft circuit breaker connects or isolates electrical power to a system. They can be opened (‘pulled’) intentionally, such as to facilitate maintenance, or they can trip to protect a system in an overload situation.

Circuit breakers incorporate a white band as a visual indicator to show that the relevant electrical system has been intentionally or unintentionally isolated (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Exemplar aircraft circuit breakers

Source: Maroomba Airlines, annotated by the ATSB

A transient overload in an aircraft system may trip a circuit breaker, but not necessarily be a defect. As a result, operators establish guidelines, based on those from the aircraft manufacturer, for flight crews to re-set circuit breakers and continue operations.

The operator’s guidelines for re-setting after a cooling period were:

- only reset if the aircraft is on the ground

- only reset if there is no recent history of reported defects with the effected or a related system and there is no evidence of anomalies with these systems

- should the breaker trip again, the cause of the trip must be rectified before another attempt to reset.

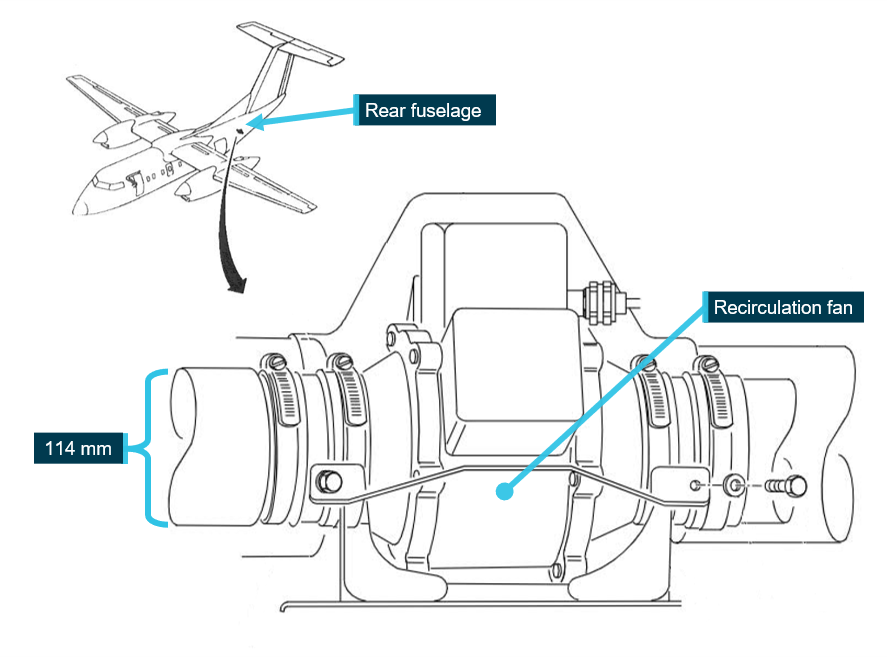

Recirculation fan

The flight compartment is pressurised by maintaining a balance between airflow entering and airflow leaving the flight compartment. On the occurrence flight, the absence of the recirculation fan allowed airflow to leave the flight compartment at a rate greater than what could be supplied, so the aircraft could not be pressurised.

Figure 3: Flight compartment recirculation fan installation

Source: De Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited, modified by the ATSB

Safety analysis

On the day of the occurrence, the aircraft was not serviceable because it had no recirculation fan fitted, which prevented it from pressurising. The removal of the fan the day before was entered into the maintenance log. However, the unserviceable status of VH‑QQD was not entered into the operations management system (AvSys) by the operations department, so the aircraft remained assigned to the flight and on the flight manifest visible by the flight crew.

The flight manifest was among the items for the flight crew to check during their pre-flight preparations. At this point, there was no reason for the flight crew to believe the aircraft was not serviceable. Although operations planning is not a means to control airworthiness, the omission on this occasion contributed to the flight crew’s confidence that VH‑QQD had been assigned to the flight and was serviceable.

Airworthiness is controlled through the use of the document suite kept on board the aircraft. This is of particular importance when a discrepancy is not obvious, such as the absence of the recirculation fan in this instance (as it was not visible during an external inspection). On the morning of the occurrence, the document suite’s unusual location provided an indication that something was wrong but would not normally be interpreted as indicating that the aircraft was unserviceable. Also, the captain likely experienced expectation bias resulting from the initial information that showed VH-QQD assigned to the flight, which would not normally occur unless the aircraft was serviceable.

The first real opportunity for the flight crew to discover the problem was the presence of unserviceabilities in the maintenance log. The operator’s flight crew operating manual required the flight crew to check the document suite when accepting the aircraft. The captain would not normally check the maintenance log unless there was a pink page present that showed permissible unserviceabilities. As there were none, the captain did not check the maintenance log. As a result, the entries for the propeller de-ice defect and the circulation fan removal were not detected.

Other documents would not have showed that the aircraft was not serviceable. For example, the maintenance release being current was not the only requirement for airworthiness. This is because the documentation suite as a whole is used to manage airworthiness rather than through individual documents.

In addition, the first officer did not check the aircraft documentation, as there was no requirement to do so. Finally, the circuit breaker that had been opened to facilitate the recirculation fan removal was another prompt for the captain to review the maintenance log for recent or open defects. However, probably due to expectation bias, the prompt was not successful on this occasion.

Ultimately, the flight crew detected the problem when they conducted the transition altitude checklist, demonstrating the importance of checklist items. Had that not occurred, the crew would have subsequently been alerted to the situation by a cabin altitude warning. Nevertheless, even though this particular occurrence was unlikely to result in an adverse outcome, it demonstrated the importance of having rigorous processes for ensuring an aircraft was serviceable prior to being used for a flight.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the cabin pressurisation issue involving a De Havilland Canada DHC-8, registered VH‑QQD, 30 km north of Perth Airport, Western Australia, on 20 November 2021.

Contributing factors

- The flight was commenced without a recirculation fan fitted to the aircraft, preventing the aircraft from pressurising.

- When reviewing the aircraft documents prior to accepting the aircraft, and after resetting a circuit breaker, the captain did not check the maintenance log for open entries. As a result, the open entry showing the recirculation fan removal was not detected.

- The operations department did not remove the aircraft from its assigned flight after receiving a message from the engineering department about the status of multiple aircraft, including that the assigned aircraft was unserviceable.

Safety actions

| Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence. |

Safety action by Maroomba Airlines

After the occurrence, the operator took the following actions:

- refined the terminology used by engineering to communicate aircraft serviceability, and reviewed internal communication methods

- distributed an internal memo to all staff advising that if the aircraft technical logs were not located in the crew room when receiving the aircraft, it was to be considered unserviceable

- distributed an internal memo to flight crews to reiterate existing paperwork and circuit breaker resetting requirements

- incorporated a dedicated compartment for each aircraft’s documents in the crew room with a placard instructing flight crews to contact maintenance watch if the scheduled aircraft’s documents were not in their compartment.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2023

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] AvSys was a third-party software system to manage the daily operational aspects of the airline’s operations, such as flight scheduling, bookings, freight management, crew scheduling, and duty times. It was not used to control aircraft serviceability.

[2] Permissible unserviceability: a defect or other issue which does not prevent aircraft operation (sometimes requiring certain conditions to be met).

[3] Radar vectoring: air traffic control provision of track bearings and altitudes used to guide and position an aircraft.