Safety summary

What happened

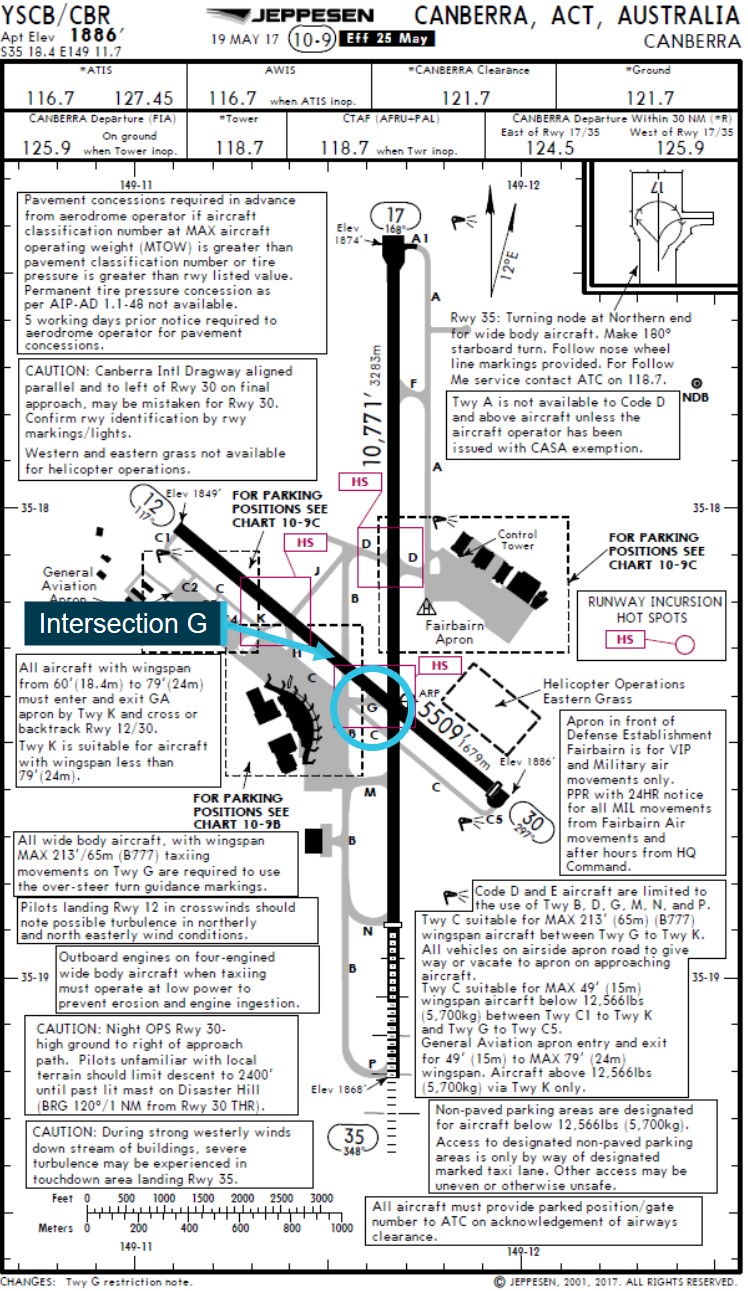

On the evening of 25 September 2019, the flight crew of a GIE Avions de Transport Régional ATR72 aircraft, registered VH-VPJ and operated by Virgin Australia Airlines, received a clearance to line‑up on runway 35 from intersection ‘Golf’ at Canberra Airport, Australian Capital Territory. While taxiing to the runway, the flight crew inadvertently lined-up on runway 30. Almost immediately after commencing the take-off roll, and at about the same time air traffic control instructed them to ‘stop’, the flight crew rejected the take‑off. The aircraft was re‑positioned for a departure from runway 35.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that the flight crew elected to depart from intersection ‘Golf’ for runway 35. Due to the close proximity of the aircraft’s parking bay to the ‘Golf’ runway holding point, the selection of this intersection reduced the distance, and therefore the amount of time available for the flight crew to complete their pre-departure checks. After passing through the holding point, the captain taxied the aircraft onto runway 30, following the lead-on lights for that runway, while the first officer’s attention was focussed on completing procedures and checklists. This likely resulted in the flight crew having reduced awareness of the runway environment and aircraft orientation.

The lead-on lights to runway 30 were active with the taxiway lighting and the lead-on lights to runway 35 were activated when the holding point stop bar at intersection ‘Golf’ was turned off by air traffic control. Therefore, both runway lead-on lights were active. This increased the risk of an aircraft being manoeuvred onto the incorrect runway, particularly at night and/or in low visibility conditions. In this case, the captain, who recalled being focused on the lead-on lights, followed the first set of lights that led to runway 30.

The ATSB also established that Virgin Australia Airlines’ ATR72 Before take-off procedure did not specify when ‘ready [for take-off]’ was to be communicated to air traffic control. This increased the risk of procedures and checklists being completed while the aircraft was taxiing onto the runway, at a time when monitoring was critical. Virgin Australia Airlines’ procedures applicable to all the aircraft in their fleet did not include a runway verification check using external cues, including runway markings, signs and/or lights.

What has been done as a result

After the incident, Virgin Australia Airlines discontinued the use of intersection ‘Golf’ for departure at Canberra Airport during the day and night. Subsequent action included a proposal to amend the ATR72 Before take-off procedure to ensure it was completed at a time when the flight crew’s attention was not diverted to other tasks. However, ATR72 operations ceased before this was implemented. In addition, Virgin Australia Airlines have developed a runway verification procedure to be included in their Flight Crew Operating Manual for the Boeing 737, their current fleet.

Safety message

The design of airport runways and taxiways vary from relatively simple to more complex layouts. This can be exacerbated by reduced visual cues, such as night-time or poor weather, which can easily increase confusion. It is important for all flight crew to familiarise themselves with these layouts, particularly any unique designs, and ensure effective flight crew co-ordination is employed to minimise the risk of a runway incursion.

Operators should ensure the design of their operating procedures minimises the risk of human error. Clearly delineating procedural steps may reduce the likelihood of flight crews’ heads down activities at critical moments throughout the flight.

What happened

On the night of 25 September 2019, at about 1840 Eastern Standard Time (EST),[1] the flight crew of a GIE Avions de Transport Régional ATR72-212A (ATR72) aircraft, registered VH‑VPJ and operated by Virgin Australia Airlines, were preparing for a scheduled passenger service from Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, to Sydney, New South Wales. The flight was planned to depart at 1900 and the captain recalled they were running ahead of schedule.

As part of their pre-flight planning, the flight crew elected to depart from intersection ‘Golf’ (G) for runway 35 (refer to section titled Canberra Airport information). The flight crew reported they based this decision on the aircraft’s performance, taking into account the weight and environmental conditions at the time, and the proximity of intersection G to their parking bay.

At about 1855, after the flight crew completed their pre-flight briefing, they requested a pushback clearance from air traffic control (ATC), which was approved. Several minutes later, the flight crew requested a taxi clearance to the holding point at intersection G, which was also approved. At around the same time, the flight crew of two other aircraft also requested clearances for pushback and taxi.

At about 1858, the captain commenced taxiing the aircraft. While taxiing to intersection G, the flight crew completed their departure review, which included checking the departure runway and intersection, take-off performance speeds and the flap setting. Before departure, there was no mention of the departure’s complexity or its designation as a hotspot. Just prior to reaching the holding point, the first officer (FO) advised ATC that they were ‘ready’ [to take-off] and then commenced the Before take-off procedure (refer to section titled Take-off performance).

At about 1859, ATC instructed the flight crew to line-up on runway 35 and about a minute later, they were cleared for take-off, with both instructions read back correctly by the FO. After the stop bar was deactivated by ATC, the aircraft crossed the holding point and the captain commenced turning through the intersection, inadvertently aligning with the centreline of runway 30.

During the turn, the FO was completing the final Before take-off checks and therefore, only looked up after the aircraft was lined-up on the runway. The captain recalled focusing on taxiing the aircraft to follow the lead-on lights (refer to section titled Airport lighting) and trying not to go too far into the intersection. Both flight crew recalled ‘the picture didn’t look right’ when they were lined-up on what they thought was the departure runway (runway 35). They also reported the runway (runway 30) appeared shorter than expected and that there was no centreline lighting (Figure 1). Neither of the flight crew could recall if they cross-checked the aircraft’s heading or position by available means as per the operator’s Before take-off procedure when they were in the lined-up position.

Figure 1: Night comparison of runway 30 and runway 35 from intersection Golf

Note: The vehicle lights were turned on in the runway 35 photograph (right).

Source: Canberra Airport, annotated by the ATSB

Air traffic control reported noticing the aircraft moving on runway 30 and immediately instructed the flight crew to ‘stop stop’ as they ‘seemed to be taking off on [runway] 30’. About 6 seconds later, the FO advised ATC they were ‘stopping’. The flight crew reported that take-off power[2] had not been applied, nor the take-off roll commenced, and no braking was required. However, recorded flight data showed an immediate increase in torque for both engines from 4-6 per cent during taxi to 17.7 per cent, as well as a decrease in brake pressure to 16 pounds per square inch (psi) after the turn onto runway 30 (Figure 2). About 4 seconds later, the engine torque reached 28.1 per cent, indicating the power levers had been advanced to commence the take-off. At about this time, ATC instructed the flight crew to stop, after which, the data showed a decrease in the power lever positions to flight idle and an increase in brake pressure to 1,686 psi.

The flight data was consistent with airport closed-circuit television footage. This footage showed the aircraft cross the holding point and line-up on runway 30, followed by a brief pause, then a short acceleration before a sudden braking. The aircraft then remained stationary on the runway for a few seconds before it was taxied forward along the runway and vacated at the next exit.

Air traffic control provided further instructions to the flight crew to taxi off runway 30 and reposition for a departure from intersection ‘November’ for runway 35. The flight continued to Sydney without further incident.

Figure 2: Flight data showing the aircraft’s turn onto runway 30 with key events

Note: The green line from taxiway golf onto runway 30 indicates the aircraft track.

Source: Virgin Australia Airlines, annotated by the ATSB

__________

Personnel information

Captain

The captain held an Air Transport Pilot (Aeroplane) Licence, multi-engine command instrument rating and a Class 1 Aviation Medical Certificate. At the time of the incident, the captain had a total of 6,500 hours of aeronautical experience, of which 2,375 hours were on the ATR72.

The captain was based in Brisbane and scheduled to travel on the 2130 service from Sydney to Brisbane on arrival in Sydney. However, during the turn‑around in Canberra, the captain contacted the airline’s crewing department to reschedule the commute to an earlier flight that departed Sydney at 2000, 10 minutes after the incident flight’s scheduled arrival time in Sydney.

First officer

The FO held a Commercial Pilot (Aeroplane) Licence, multi-engine instrument rating and a Class 1 Aviation Medical Certificate. At the time of the incident, the FO had a total of 6,700 hours of aeronautical experience, of which 6,100 hours were on the ATR72.

Experience in Canberra

Both the captain and the FO reported regularly operating from Canberra Airport over a number of years during both the day and night and being familiar with the airport’s layout. However, they could not recall previously using intersection G for departure at night but had used it for departure at least once during the day.

Fatigue considerations

A review of the sleep and roster information obtained found there was a low likelihood the flight crew were experiencing a level of fatigue known to have an adverse effect on performance.

Canberra Airport information

Canberra Airport has two runways, 17/35,[3] with a length of 3,283 m and width of 45 m; and 12/30, with a length of 1,679 m and width of 30 m. At the time of departure, both runway 30 and 35 were active.

The intersection departures available for runway 35 were from taxiways ‘Golf’ (G), ‘Mike’, ‘Papa’, and ‘November’ (Figure 3). Taxiway G leads to the intersection of the two runways 17/35 and 12/30 and is listed as a runway incursion hotspot due to this complex layout (refer to section titled Runway incursions). There are few airports in Australia where a taxiway led to the intersection of two runways.

Figure 3: Canberra Airport chart

Source: Virgin Australia Airlines, annotated by the ATSB

Airport signs

Canberra Airport had runway and taxiway signs as per the Civil Aviation Safety Authority’s Part 139 Manual of Standards for Aerodromes and International Civil Aviation Organization’s Annex 14: Aerodromes. However, these documents do not include standards for signs at taxiways that lead to the intersection of two runways. Intersection G had a red runway sign for 12/30 on the left and a runway sign for 17/35 on the right of the taxiway when viewed from the cockpit (Figure 4). Adjacent to the holding point lights on the left side of the taxiway was the yellow runway distance remaining board for runway 35.

Figure 4: View of intersection G at Canberra Airport

Source: Canberra Airport, annotated by the ATSB

In comparison, the United States Federal Aviation Administration Aeronautic Information Manual stated that if a sign was located on a taxiway that intersects the intersection of two runways, the designation for both runways should be shown on the sign along with arrows showing the approximate runway alignment of each runway. In addition to showing the approximate runway alignment, the arrow indicates the direction to the threshold of the runway whose designation is immediately next to the arrow (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Federal Aviation Administration standards for signs at holding points with two runways

Source: Federal Aviation Administration

While intersection G was a complex layout, the runway signs were consistent with the applicable standards. Although other signs could be used at taxiways that lead to the intersection of two runways, such as those shown above, there were no other incidents reported for Canberra Airport where an aircraft had been inadvertently taxied onto the wrong runway from intersection G.

Airport lighting

The lighting system at Canberra Airport included runway lighting and taxiway lighting (Figure 6). Runway lighting consisted of white lights on the edges of the runway, and green and red lights positioned at the ends of the runway landing and departure thresholds respectively. Taxiway lighting consisted of green centreline lighting. There were also red stop bar lights at all the holding points for both runways. Only runway 17/35 had white centreline lighting.

Stop bars are installed at runway entry points to prevent an aircraft inadvertently entering the runway without a clearance. The lead-on lights for runway 35 from intersection G were linked with the stop bar so that when the stop bar was deactivated by ATC, the green centreline lighting beyond the stop bar activated. The lead-on lights for runway 30 were on the same circuit as the taxiway lighting, and therefore already active irrespective of the state of the stop bar. Therefore, it was possible for the lead-on lights to both runway 30 and 35 to be illuminated at the same time.

Figure 6: Canberra Airport lighting

Source: Canberra Airport, annotated by the ATSB

Operational information

Aircraft performance

From intersection G, there was 1,810 m of take-off run available[4] and 1,870 m of take-off distance available[5] for departure from runway 35. For runway 30 there was 1,030 m of take-off distance available. Factoring the aircraft’s weight and environmental conditions, about 1,700 m was required for the take-off. The accelerate stop distance[6] required for either runway was about 1,650 m.

Given the shorter length of runway available for take-off from intersection G, the aircraft’s limitations for using this intersection was a maximum take-off weight of 20,541 kg and maximum air temperature of 31 °C. At the time of the incident, the aircraft’s actual take-off weight was 20,000 kg and the ambient air temperature was recorded as 11 °C.

As part of an internal review following the incident, Virgin Australia Airlines examined the ATR72 specific departure data from Canberra Airport for the 9 months prior to the incident. The data showed that 4 per cent of all ATR72 departures were from intersection G during both the day and night. Less than 1 per cent of all departures were from intersection G at night.

Simulator session

To assess the outcome of a take-off from runway 30, Virgin Australia Airlines conducted a simulator session. The same data as the incident flight was loaded into the simulator and the flight crew briefed an intersection G departure from runway 35. When the flight crew reached the intersection of runway 30 and 35, they were instructed to keep turning until they were lined-up on runway 30. Since the aircraft was lined-up near the intersection of the runways, the course deviation bar was observed to be centred.

The flight crew conducted the take-off, applying full torque of 90 per cent. The aircraft reached a height of 50 ft at the upwind threshold and continued without any terrain warnings. The scenario was repeated with an engine failure after take-off, which resulted in the flight crew receiving a terrain warning. Based on the results from these sessions, it was assessed that the take-off could have been successful if the departure was continued from runway 30. However, a runway overrun would have likely occurred if these was an engine failure at around their selected V1[7] speed, or if there was any mishandling of the take-off. The operator’s flight technical specialists reviewed the flight data and conditions on runway 30 on the night of the incident and estimated around 980 m was required for the aircraft to become safely airborne using a minimum rotate/unstick airspeed.

Operator procedures

Take-off performance

At the time of the incident, Virgin Australia Airlines did not publish ATR specific performance charts for departure using runway 12/30. Therefore, the flight crew were restricted to using runway 17/35 only.

Before take-off procedure and checklist

In preparation for departure, the flight crew were required to complete the Before take-off procedure and checklist specified in Virgin Australia Airlines’ ATR72 Standard Operating Procedures. This procedure was to be completed after the cabin was secure and the departure review had been conducted. The procedure did not include a step for when ‘ready’ [for take-off] should normally be reported to ATC, and the flight crew recalled they would often report ‘ready’ [for take-off] prior to commencing the Before take-off procedure. By comparison, calling ‘ready’ was placed at the end of Virgin Australia Airlines’ Boeing 737 Before take-off procedure.

The ATR72 procedure referred to flight crew member 1 (CM1) as the pilot in the left seat (the captain) and flight crew member 2 (CM2) as the pilot in the right seat (the FO). Each flight crew member was assigned specific tasks to complete, which were applicable to all flights. Table 1 lists the tasks to be completed as part of the Before take-off procedure. Of note, the second to last item was required to be performed prior to entering the runway for take-off and the last item was to be completed on the runway. On the evening of the incident, the flight crew allowed themselves less than 90 seconds to complete this procedure while taxiing to the intersection. In comparsion, taxiing to the other intersections closer to the runway end would have taken several minutes, allowing more time to complete this procedure.

Table 1: Virgin Australia Airlines ATR72 Before take-off procedure

| CM1 (captain) | CM2 (FO) |

| Call ‘cabin secure’ and turn over the CABIN SECURE card to display the green lettering ‘secure’. | |

| Conduct the take-off review, which involves verifying their assigned runway and calculated speeds. | |

| Call ‘gust lock’, check for unrestricted rudder travel, and check rudder cam is centred. | Release gust lock and check for unrestricted aileron and elevator travel in all directions and check spoiler lights. |

| Set the bleed valves in accordance with performance data calculations and check airflow is selected to NORM. | |

| Call ‘before take-off checklist’ | Check the flight controls and confirm the bleed valves/airflow were set. Then call ‘before take-off checklist’ complete. |

| Immediately prior to entering the runway for take-off or when back tracking the runway (as appropriate) cycle the NO DEVICE switch to achieve the two audible chimes. | |

| When on the runway both the flight crew are required to verify they are lined up on the centreline by checking the flight director lateral bar is centred when in the lined-up position. |

Note: This table combined the Before take-off procedure and checklist provided by Virgin Australia Airlines.

The Before take-off procedure also specified that flight crew were required to verify the aircraft had lined-up on the correct runway using internal cues within the cockpit such as those provided by the horizontal situation indicator.[8] Specifically, the procedure stated:

Use all available information such as heading and [flight management system] course indication [primary flight display],[9] lateral profile [multi-function display][10] and departure runway [multi‑function control and display unit][11] to ensure the aircraft is at the assigned runway and correct intersection for take-off.

Virgin Australia Airlines’ procedures applicable to all fleet did not include the use of external cues to verify the aircraft’s position prior to entering the runway and/or commencing the take-off roll at all times. The only reference to checking the take-off runway was during low visibility operations. External cues include runway markings, lights, and signs. An informal review of other operators’ procedures found they included a runway verification check, which was conducted prior to take‑off. This procedure required the flight crew to confirm the runway entry point prior to entry, and the departure runway prior to commencing take-off, with reference to both internal and external cues. This procedure would be conducted by both flight crew, and it required them to verbalise the identification and verification.

Runway incursion prevention

Virgin Australia Airlines’ Operations Manual: Operating Policies and Procedures applicable to all aircraft in their fleet described strategies to assist flight crew to manage the risk of runway incursions. These strategies included:

To avoid a runway incursion, flight crew must maintain a high level of situational awareness and vigilance during taxi, both before take-off and after landing. The following will assist flight crew in achieving this:

1. The Pilot Flying (PF) should brief the anticipated taxi route during the departure or approach briefing, as applicable, when:

a. Complex taxi routing is expected; or

b. Advice including NOTAMs affect taxiway routing or runways; or

c. Active runways will be crossed; or

d. Runway incursion 'hotspots' are identified on airport charts.

Ensure the aircraft location and that of other proximate traffic is known at all times by use of airport signage and reference to the airport diagram chart. Navigation displays should be used to aid orientation whenever practicable. During complex taxiing the [pilot monitoring] may assist awareness by verbal confirmation of taxiway passage or clearances.

Administrative tasks and checklists should be accomplished at the appropriate time, with due consideration to active runway or ‘hotspots’ on the taxi route.

Prior to crossing a runway or entering a runway for take-off the flight crew must:

a.) Verify the correct runway.

b.) Confirm that there is no conflicting traffic on the runway or on approach. Use of Traffic Collision Avoidance System may assist in the display of traffic but does not preclude visual verification.

Runway incursions

The International Civil Aviation Organization (2007) define runway incursions as:

Any occurrence at an aerodrome involving the incorrect presence of an aircraft, vehicle or person on the protected area of a surface designated for the landing and take-off of aircraft.

Incident reports show runway incursions are often clustered at particular runway holding points and/or intersections. These are known as ‘hotspots’. Specifically, a runway incursion hotspot is defined as ‘a location on an aerodrome movement area with a history or potential risk of collision or runway incursion, and where heightened attention by pilots/drivers is necessary’ (International Civil Aviation Organization 2007). These hotspots are included on charts provided by Airservices Australia and Jeppesen. Virgin Australia Airlines provided their flight crew with Jeppesen charts for their flight planning.

According to Airservices Australia’s Pilot’s Guide to Runway Safety (2016) a reason why runway incursions occur was due to runway confusion, which is when pilots enter, take-off, or land on the incorrect runway. The risk increases at airports with multiple runways, complex layouts or during night operations. One countermeasure to avoid runway confusion was to visually identify the correct runway before you enter or land on it using available cues such as signage, orientation, and runway markings.

An ATSB research report Factors influencing misaligned take-offs at night reviewed Australian and international occurrences where aircraft lined up on runway edge lighting or departed from closed/incorrect runways or taxiways. Common themes identified in these occurrences were flight crew divided attention/distraction/eyes inside (including due to workload and lack of familiarity with runway or airport) and confusing runway/taxiway entry/lighting.

The Pilot’s guide to runway safety also provided the following considerations to avoid runway incursions (not limited to):

- plan the taxi using available airport charts

- minimise heads down activity while the aircraft is moving

- resist the pressure to take short cuts.

Similar occurrences

A review of the ATSB’s occurrence database did not find any other incidents where an aircraft entered runway 30 instead of 35 at Canberra Airport while taxiing from intersection G in the previous 5 years. The following incidents were identified where aircraft had been lined-up on the incorrect runway or intersection:

ATSB investigation AO-2017-008

On 21 January 2017, the flight crew of an Airbus A320 aircraft, registered VH-VNC, prepared to conduct a regular passenger service from Cairns to Brisbane, Queensland.

At about 1511, ATC cleared the flight crew to taxi to holding point ‘B5’, which was the clearance they had expected and briefed. The aircraft was then taxied behind another aircraft along taxiway B. However, as that aircraft entered the runway from taxiway ‘B4’, the FO of VH-VNC inadvertently also taxied to holding point B4. At about 1515, the captain advised ATC that they were ready for take-off. Air traffic control cleared the flight crew to line up on the runway. The FO taxied the aircraft onto the runway and the flight crew completed the pre-take-off checks.

About 1 minute later, ATC cleared the flight crew to take-off. Immediately after, the captain read back the take-off clearance and ATC advised the flight crew that they were lined up at the B4 (not B5) intersection. The take-off clearance was cancelled. The aircraft subsequently took off from the B5 intersection and the flight continued without incident. Intersection B4 was 403 m shorter than B5.

The investigation noted that the pre-take-off checklist required the flight crew to verbally confirm that they were on the correct runway. However, reference to an intersection was not part of the verbal check/response. The FO commented that confirming the intersection as well as the runway during the pre-take-off checks may prevent a similar incident occurring.

ATSB investigation AO-2007-064

On 25 November 2007, a Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation G-IV aircraft, registered HB-IKR, was being operated on a charter flight from Brisbane, Queensland to Sydney, New South Wales. At about 2225, the pilot in command of the aircraft commenced a take-off run on taxiway Alpha, adjacent to the active runway 01. Air traffic control instructed the pilot to cancel the take-off clearance. The flight crew stopped the take-off and ATC instructed them to taxi to the end of the runway for a take-off using the full runway length.

The investigation identified various factors that contributed to the attempted take-off on the taxiway, including the take-off being conducted at an intersection departure from taxiway A7, which did not have normal runway threshold markings. Further, there was increased workload for the captain and possible self-imposed time pressure.

__________

- Runway numbering: represent the magnetic heading closest to the runway orientation (e.g. runway 35 is orientated 348º magnetic).

- Take-off run available: the length of runway declared available and suitable for the ground run of an aircraft taking off.

- Take-off distance available: the length of the take-off run available plus the length of the clearway at the end of the runway.

- Accelerate stop distance required (all engines operating): The sum of the distances required to accelerate from the brakes release point to V1 (decision speed for critical engine failure) with all engines operating and then to decelerate to come to a full stop plus the distance travelled at V1 in 2 seconds.

- V1: the critical engine failure speed or decision speed required for take-off. Engine failure below V1 should result in a rejected take off; above this speed the take-off should be continued.

- Horizontal situation indicator: A direction indicator that includes a magnetic compass, which provides the location of the aircraft in relation to a chosen course or radial.

- Primary flight display: presents information about primary flight instruments, navigation instruments, and the status of the flight in one integrated display.

- Multi-function display: used for traffic, route selection, and weather and terrain avoidance.

- Multi-function control and display unit: used to input and modify flight plans.

Introduction

On the evening of 25 September 2019, the flight crew of a GIE Avions de Transport Régional ATR72 aircraft, registered VH‑VPJ and operated by Virgin Australia Airlines, received a clearance to line-up on runway 35 from intersection ‘Golf’ (G) at Canberra Airport, Australian Capital Territory. The aircraft was inadvertently taxied onto runway 30 and the take-off roll was commenced. The flight crew rejected the take-off about the same time as air traffic control (ATC) issued them an instruction to ‘stop’.

This analysis will discuss the flight crew’s actions and responsibilities prior to take-off, and the runway lighting characteristics. It will further discuss Virgin Australia Airlines’ Before take-off procedures and the cues used to verify an aircraft’s position in relation to the runway environment.

Line-up on incorrect runway

Shortly after the flight crew were cleared for take-off on runway 35 at night by ATC, the captain inadvertently taxied the aircraft onto runway 30. After lining-up on runway 30, the engine power increased and brake pressure decreased, which was consistent with commencing the take-off roll. The recorded flight data was consistent with the airport closed-circuit television footage of the aircraft’s movements on the taxiway and runway 30.

While the flight crew did not recall commencing the take-off roll, they did notice there were differences in the runway environment to what they were expecting and discussed it with each other. Specifically, there was no centreline lighting and the runway appeared shorter than expected. The abrupt rejection of the take-off at about the same time ATC issued the ‘stop’ instruction was consistent with the flight crews’ reported awareness of a problem with the runway environment.

Time pressure before take-off

The flight crew elected to depart from intersection G for runway 35 primarily due to its proximity to their parking bay and this departure was within the performance limits. Although there were no delays on the night of the incident and the flight was reported to be running early, it was possible that the flight crew were also attempting to depart ahead of the other two aircraft, particularly given the captain’s rescheduled flight to Brisbane. However, neither flight crew recalled these factors influenced their decision to use intersection G for departure.

By selecting intersection G, the flight crew only allowed themselves around 90 seconds to complete their preparatory tasks before arrival at the holding point. These tasks included the departure review and Before take-off procedure. If they had selected another taxiway entry to runway 35, they would have had several additional minutes before arrival at the respective holding point in which to complete their checks.

This self-imposed time pressure led to the First Officer (FO) calling ‘ready’ as the aircraft taxied to the holding point for intersection G and prior to completing the Before take-off procedure. This procedure should have been completed before entering the runway, with the exception of the last item in the procedure to confirm that they were lined-up on the runway’s centreline. This resulted in the FO’s attention being diverted to the procedure when entering the runway environment.

Reduced awareness of the runway environment

On the night of the incident, the flight crew elected to depart from intersection G for runway 35. Although they operated routinely to Canberra Airport, they both reported they could not recall having departed from this intersection at night. After pushback and while taxiing towards intersection G, the flight crew briefed the departure, but did not specifically include the layout of the intersection in their brief.

As they approached intersection G, the FO reported focusing on the Before take-off procedure and was therefore not monitoring the external environment. The captain reported being focussed on the lead-on lights. However, the Before take-off procedure was a challenge and response procedure, and therefore would have required some of the captain’s attention. This likely resulted in the captain taxiing the aircraft through the intersection with divided attention while the FO’s attention was focussed inside the cockpit. Barshi and others (2009) reported that during busy periods, it is easy for attention to be absorbed in one task, which can divert attention from other important tasks, such as monitoring.

Neither flight crew could recall if they checked the aircraft’s heading after line-up. As they subsequently commenced the take-off roll, they had not identified they were lined-up on the incorrect runway. This indicated the flight crew had a reduced awareness of their position within runway environment.

Lead-on lights from intersection ‘Golf’

Taxiway G led to the intersection of runway 12/30 and runway 17/35. This intersection was identified as a hotspot, which could potentially be confusing to flight crew, particularly at night. When ATC issued the line-up clearance to the flight crew from this intersection, the stop bar was selected off by ATC and the lead-on lights for runway 35 illuminated. The lead-on lights for runway 30 were already illuminated with the taxiway lighting, which resulted in the lead-on lights for both runways illuminated at the same time. As the lead-on lights for runway 30 were the first set encountered when entering the intersection, these lights likely drew the captain’s attention, resulting in the aircraft being manoeuvred to follow them.

A risk when operating at an airport with a complex layout at night and/or low visibility conditions is runway confusion, where pilots enter, take-off, or land on the incorrect runway (Airservices Australia 2016). This can occur when features of the taxiway or runway, such as lighting are misidentified. While there were no other known incidents at Canberra Airport, the simultaneous activation of the lead‑on lights at intersection G increased the risk of an aircraft being manoeuvred onto the incorrect runway.

ATR72 before take-off procedure

The flight crew called ‘ready’ prior to commencing the Before take-off procedure on the night of the incident, which they reported they had done frequently. However, the Virgin Australia Airlines ATR72 Standard Operating Procedure did not specify a particular time when the flight crew were to make this call to ATC. By comparison, calling ‘ready’ was specified as the final item in the operator’s Boeing 737 Before take-off procedure, meaning that there were no further tasks to be completed until the flight crew received their take-off clearance from ATC.

Degani and Weiner (1993) as well as Barshi and others (2016) research into checklist design concluded that checklists should be designed in such a way that their execution will not be integrated with other tasks. They suggested countermeasures could include carefully examining the content and timing of procedures and checklists, such as specifying the tasks that must be completed at specific points in each phase of flight. Specifically, the timing of the procedure and checklist should minimise the risk of interruptions, distractions, and concurrent tasks. Similarly, Virgin Australia Airlines and Airservices Australia provide general guidance to consider the timing of tasks, such as avoiding heads down activity while the aircraft is moving.

For the incident flight, the timing of the ‘ready’ call resulted in the aircraft crossing the holding point and entering the runway with the FO focussed on checklist items. Consequently, the FO was unable to monitor the environment as the aircraft entered the runway to line-up.

Therefore, the omission of a step in the ATR72 Before take-off procedure for the ‘ready’ call, increased the risk of flight crews actioning this procedure while entering the runway. In turn, diverting their attention to checklist items at a time when monitoring and verifying the runway environment was critical.

Runway verification cues procedure

Virgin Australia Airlines’ ATR72 Standard Operating Procedure and fleet-wide policy and procedures draw reference to the importance of verifying the aircraft is on the correct runway. However, the only cues listed in the ATR72 Before take-off procedure to achieve this related to internal cues such as the cockpit instruments, including the horizontal situation indicator. The only other reference to external runway verification cues was in specific reference to low visibility operations.

The external cues available to the flight crew at the intersection G holding point prior to runway entry included the airport chart and runway marker boards. The cues to indicate they were on runway 30, in addition to the aircraft instruments, were the absence of centreline lighting, the presence of the apron lighting and the proximity of the runway end lights.

Other operators, particularly those operating into airports with complex layouts, include a runway verification procedure. This procedure would require the flight crew to verbalise their identification and verification of the runway entry point prior to entry, and the departure runway prior to commencing take-off using available internal and external cues. Making use of all available external cues at an airport, including signs, lighting, and markings will improve awareness of the environment and reduce the risk of runway incursions (Federal Aviation Administration 2016).

To avoid a runway incursion or overrun event, operators and flight crew need to ensure the aircraft enters the correct runway from the correct holding point and is then lined-up on the correct runway for take-off. The inclusion of a published procedure could promote a habit of directing attention to both internal and external cues, to verify the aircraft’s position in the runway environment.

Detection of incorrect runway

When the flight crew lined-up and commenced the take-off roll on runway 30, ATC immediately issued a stop instruction. At around the same time, the flight crew rejected the take-off and commenced braking. The ATSB’s calculations based on the runway length and the aircraft’s performance data showed that there was insufficient distance available on runway 30 for the aircraft to take-off. Virgin Australia Airlines conducted simulator sessions that demonstrated a successful take-off was possible if there were no abnormal conditions.

Therefore, had neither the flight crew nor ATC detected the aircraft was lined-up on the incorrect runway, it was possible that the take-off would have been achieved. However, if an engine failure occurred near V1, or if the take-off was mishandled, there was a risk of a runway overrun due to the shorter runway length.

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition, ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. Safety issues are highlighted in bold to emphasise their importance. A safety issue is a safety factor that (a) can reasonably be regarded as having the potential to adversely affect the safety of future operations, and (b) is a characteristic of an organisation or a system, rather than a characteristic of a specific individual, or characteristic of an operating environment at a specific point in time. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the take-off being commenced on the wrong runway involving GIE Avions de Transport Régional, ATR72, VH‑VPJ, Canberra Airport, Australian Capital Territory, on 25 September 2019.

Contributing factors

- At night, the flight crew inadvertently lined-up and commenced the take-off roll on runway 30, rather than the assigned runway 35. The flight crew and air traffic control noticed the error about the same time and the take-off was rejected.

- The runway intersection selected reduced the taxi time, resulting in the flight crew announcing they were 'ready' before completing the 'before take-off' procedure.

- While taxiing onto the runway, the captain was focused on following the runway lead-on lights while the first officer was completing the Before take-off procedure and checklist. This likely resulted in them having a reduced awareness of the runway environment and aircraft orientation.

- When the runway holding point stop bar at intersection Golf was turned off, the lead-on lights to both runway 30 and 35 were illuminated. This increased the risk of an aircraft being manoeuvred onto the incorrect runway, particularly at night and/or in low visibility conditions.

- The Virgin Australia Airlines Before take-off procedure did not include a step to report ‘ready’ to air traffic control. This increased the risk of flight crews completing this procedure while entering the runway, diverting their attention to checklist items at a time when monitoring and verifying was critical (Safety issue).

- Virgin Australia Airlines did not require flight crew to confirm and verbalise external cues such as runway signs, markings, and lights to verify an aircraft’s position was correct prior to entering and lining up on the runway (Safety issue).

Other findings

- The immediate response of air traffic control and the flight crew with rejecting the take-off, reduced the risk of a runway overrun.

|

Central to the ATSB’s investigation of transport safety matters is the early identification of safety issues. The ATSB expects relevant organisations will address all safety issues an investigation identifies. Depending on the level of risk of a safety issue, the extent of corrective action taken by the relevant organisation(s), or the desirability of directing a broad safety message to the aviation industry, the ATSB may issue a formal safety recommendation or safety advisory notice as part of the final report. All of the directly involved parties are invited to provide submissions to this draft report. As part of that process, each organisation is asked to communicate what safety actions, if any, they have carried out or are planning to carry out in relation to each safety issue relevant to their organisation. Descriptions of each safety issue, and any associated safety recommendations, are detailed below. Click the link to read the full safety issue description, including the issue status and any safety action/s taken. Safety issues and actions are updated on this website when safety issue owners provide further information concerning the implementation of safety action. |

Timing of 'before take-off' procedure

Safety issue number: AO-2019-055-SI-01

Safety issue description: Virgin Australia Airlines did not require ATR flight crews to complete the Before take-off procedure prior to reporting ‘ready’ to air traffic control. This increased the risk of flight crews completing this procedure while entering the runway, diverting their attention to checklist items at a time when monitoring and verifying was critical.

Runway verification cues

Safety issue number: AO-2019-055-SI-02

Safety issue description: Virgin Australia Airlines did not require flight crew to confirm and verbalise external cues such as runway signs, markings, and lights to verify an aircraft’s position was correct prior to entering and lining up on the runway.

Safety action not associated with an identified safety issue

| Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence. |

Discontinuation of departures from intersection G

After the incident, Virgin Australia Airlines issued a flight notice to all flight crew advising departures using intersection G at Canberra Airport would be discontinued. All performance platforms on the ATR72 were updated and the Canberra ‘TWY G’ intersection departure was removed.

Proposed changes to the ‘Before take-off’ procedure

Virgin Australia Airlines approved changes to the ATR72 standard operating procedure to include an additional statement highlighting the checklist must be completed before entering the runway. However, ATR72 operations ceased prior to the implementation of this change.

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- the flight crew

- Virgin Australia Airlines

- Airservices Australia

- Canberra Airport.

References

Airservices Australia 2016, A pilot’s guide to runway safety. Airservices Australia.

Barshi, I, Loukopoulos, LD & Dismukes, RK 2009. The multitasking myth: Handling complexity in real-world operations. Ashgate Publishing Aldershot.

Barshi, I, Mauro, R, Degani, A. & Loukopoulou, L 2016, Designing flightdeck procedures, National Aeronautics and Space Administration Technical Memorandum NASA/TM—2016–219421

Civil Aviation Safety Authority 2017, Manual of Standards Part 139 - Aerodromes. Canberra: CASA.

Degani A & Wiener EL 1993, ‘Cockpit checklists: Concepts, design, and use’, Human Factors, vol. 35(2), pp.345–59.

Federal Aviation Administration 2016, Pilot’s handbook of aeronautical knowledge FAA-H-8083-25B. US Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration, Flight Standards Service.

Federal Aviation Administration 2020, Aeronautical Information Manual. US Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration.

International Civil Aviation Organization 2007, Manual for the prevention of runway incursions (Doc 9870), Montreal: ICAO.

International Civil Aviation Organization 2018, Aerodromes - Volume 1: Aerodrome design and operations (8th edition), International Civil Aviation Organization.

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties: the captain, first officer, the tower controller, Airservices Australia, Virgin Australia Airlines, Canberra Airport, and Civil Aviation Safety Authority.

Submissions were received from Virgin Australia Airlines, Canberra Airport, and the first officer. The submissions were reviewed and where considered appropriate, the text of the draft report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2020

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |