Safety summary

What happened

On 12 February 2017, the fully-laden bulk carrier, Aquadiva, was departing Newcastle Harbour under the conduct of a harbour pilot. At about 2218 Australian Eastern Daylight Time (AEDT), during Aquadiva’s passage through a section of the harbour channel known as The Horse Shoe, insufficient rudder was applied in time to effectively turn the ship. The ship slewed, or moved laterally (sideways), toward the southern edge of the channel, and at 2224 it was over the limits of the marked navigation channel. Additional tugs were required to arrest the ship’s movement and return it to the channel to complete its departure.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that bridge resource management (BRM) techniques were not effectively implemented throughout the pilotage. In particular, the harbour pilot’s passage plan was not provided to the ship’s crew prior to his boarding. As a result, the harbour pilot’s passage plan was different to that of the ship’s bridge crew’s. This meant they did not share the same mental model of the planned passage, and were unable to actively monitor the progress of the ship or the actions of the pilot.

As a consequence, the safety net usually provided by effective BRM was removed and the pilotage was exposed to single-person errors. Such errors, when they occurred, were not identified or corrected. When insufficient rudder was applied and the ship did not turn as expected, no-one from the ship’s bridge crew challenged or intervened to draw this error to the attention of the harbour pilot. Consequently, the ship travelled too close to shallow water.

The ATSB also found that ambiguities in the details of the incident (whether the ship touched bottom or not) and in reporting requirements, as understood by relevant responsible persons (as defined by the Transport Safety Investigation Regulations 2003) led to delays in the reporting of the incident to authorities, including the ATSB. These delays meant that evidence available at the time of the incident, such as voyage data recordings, were not collected.

What's been done as a result

As a result of this incident, the Port Authority implemented a training and information process with pilots to discuss the incident and its outcomes and to inform them of their incident reporting obligations. Also, procedures are to be updated to require the use of portable pilotage units on all pilotages, and a project to implement sharing of electronic passages plans is also being undertaken.

Aquadiva’s operator provided targeted training to the ship’s officers. The company also completed an internal investigation and circulated the report and discussed and implemented identified preventive and corrective actions throughout its fleet.

Safety message

Safe and efficient pilotage requires clear, unambiguous, effective communication and information exchange between all active participants. An agreed passage plan, its understanding and the establishment of a ‘shared mental model’ between a harbour pilot and a ship’s crew, forms the basis for a safe voyage. Without this, effective implementation of BRM techniques will be limited, removing the intended safety net provided by BRM and, in this instance, leaving the passage exposed to potential single-person errors.

On 11 February 2017, the dry bulk carrier, Aquadiva (Figure 1), arrived at Kooragang number 8 berth, Port of Newcastle, for cargo loading. At 1209[1] on 12 February, cargo loading was complete and preparations were made for departure on the evening high tide, due at 2250. Aquadiva had departure draughts of 15.24 m fore and aft.

Figure 1: Aquadiva

Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau

Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau

At 2000, the ship’s crew completed pre-departure checks. The ship’s berth-to-berth passage plan for the voyage included nine course alteration positions (waypoints) for the departure pilotage from the berth to the pilot disembarkation point. The passage plan included advice to ‘follow courses laid on the ECDIS (Electronic Chart Display and Information System)’ and ‘monitor the vessel’s position’.

At 2048, a Newcastle harbour pilot boarded the ship. The master and pilot commenced the master-pilot information exchange (MPX) and discussed the pilotage. Tug requirements, position and repositioning were explained during the exchange. Four tugs were to be in attendance: Mayfield on the centre lead forward, Svitzer Hamilton on the centre lead aft, Svitzer Meringa on the port shoulder and Svitzer Myall on the starboard shoulder.

At 2112, at nearby Kooragang berth number 4, a similar sized ship (FPMC B Justice - 300 m long, 50 m beam, 207,000 deadweight tonnes) departed ahead of Aquadiva. The plan of the pilot of Aquadiva was to remain mid-channel, passing through the Newcastle port passage plan waypoints. He was to remain at least 1,000 m behind the ship in front to minimise any hydrodynamic interaction between the two ships.

Passage to the wheel over point for The Horse Shoe

At 2123, with the four tugs in attendance, dead slow ahead was ordered and Aquadiva was under way (Figure 2 and appendix A). The pilot conned Aquadiva south, clear of Kooragang Island, and into the Steelworks Channel at about 3 knots.[2] At 2203, the pilot ordered slow ahead on the main engine and the ship’s speed increased.

Figure 2: Extract from navigational chart Aus 207 showing Aquadiva’s track departing Newcastle; position times and port waypoints (WP) indicated

Source: Australian Hydrographic Service; annotations by ATSB

Source: Australian Hydrographic Service; annotations by ATSB

At 2204, the pilot directed the master of the tug Svitzer Myall to reposition from the starboard shoulder to the port quarter. The tug master experienced some difficulty positioning the tug due to the ship’s stern cut away. The tug was repositioned further forward on the port side but was hampered due to the position of the accommodation ladder, which was not fully housed. By 2212, the tug was in position, forward of the ship’s accommodation, adjacent to the aftermost hatch.

At 2214, as Aquadiva passed waypoint 9 (WP9) at about 4 knots, the pilot ordered half ahead. The ship had a speed of 5.1 knots as it approached the alteration to port through The Horse Shoe. The alteration was more than 90°, from about 153° onto a heading of 056° leading out past Nobbys Head and to sea.

Passage through The Horse Shoe

The pilot’s plan was for a speed of about 4.7 knots as the ship approached the wheel over point (WOP)[3] for the alteration, about 120 m before WP8 (Figure 3). At 2218, at 5.1 knots, the pilot ordered 10° of port rudder followed by 20°. He wanted a rate of turn of about 13°/minute and he closely monitored the ship’s rate of turn indicator, which was mounted overhead in the bridge front. The ship’s bow turned to port while the ship continued to track almost straight ahead. Hard port rudder was ordered and, at 2220, the ship began to slow and turn to port. The pilot reported that he continued to focus on the rate of turn indicator to see if the ship was turning as quickly as desired.[4]

Figure 3: Extract from navigational chart Aus 208 showing Aquadiva’s track through The Horse Shoe

Source: Australian Hydrographic Service; annotations by ATSB

Source: Australian Hydrographic Service; annotations by ATSB

A short time later when he checked the ship’s position by looking out of the windows, the pilot saw that the ship was deeper into The Horse Shoe than expected. It was now south of his intended track and closing on the east cardinal buoy[5] (Birubi buoy). The buoy indicated safe water to the east and the outer limit of the channel, maintained to a depth of 15.2 m. At 2221, the pilot contacted the tugs to assist the turn. He requested Svitzer Meringa (on the port shoulder) to come astern and Svitzer Myall (port quarter) to take the ship’s stern to starboard. Astern of the ship, the master of Svitzer Hamilton (centre lead aft) expressed concern that his tug would contact Birubi buoy. The pilot then requested Mayfield (centre lead forward) to take the ship’s bow to port.

Aquadiva’s master was following the progress of the ship and noted that it was deep into the turn. However, the pilot had ordered full rudder and engaged the tugs to assist the turn and the master, having little additional to contribute, did not challenge or intervene.

Nearby, the four tugs, which had assisted FPMC B Justice, were returning along the southern side of the channel. At 2221, the master of one of these tugs, PB Darling, having noticed Aquadiva was too far south in the channel, called the pilot and offered assistance. The pilot accepted the offer.

At this stage, Aquadiva was north of Birubi buoy with a speed of 4.9 knots, on a heading of 116° and course over the ground of 134°. At 2222, the pilot ordered the main engine slowed and then astern. At 2223, now past the buoy (Figure 4) the engine was briefly at full astern before being returned to stop and then dead slow ahead.

Figure 4: Relative positions of Aquadiva and tugs at 2223

Yellow line indicates the track followed by FPMC B Justice. The blue lines join passage plan waypoints.

Source: Australian Maritime Safety Authority and ATSB

At about the same time, Svitzer Hamilton had avoided Birubi buoy and repositioned to apply weight to take the ship’s stern to starboard. PB Darling had also been manoeuvred to push up on the ship’s starboard shoulder to move the bow further to port.

Aquadiva’s speed continued to reduce. At 2224, the speed was 2.6 knots and the ship’s bow continued to swing to port. The ship was now on a heading of 087° and positioned along the southern edge of the channel. The pilot ordered all tugs to stop. The ship continued to swing to port and, at 2225, was on a heading of 068° with a speed of about 2 knots (Figure 5). The pilot then ordered slow ahead, followed by half ahead on the main engine. From this point, the ship was successfully manoeuvred back into the channel.

Figure 5: Aquadiva in its most southerly position at 2225

Source: Australian Maritime Safety Authority and ATSB

At 2228, the additional tugs were released and by 2230 the ship had returned to the intended route. The remainder of the pilotage continued without further incident. By 2242, the pilot had released the four tugs and at 2250 he disembarked the ship by helicopter. At 2330, Aquadiva commenced sea passage, destined for Map Ta Phut, Thailand.

Post occurrence events

Upon returning ashore, the pilot telephoned the Newcastle harbour master and left a message about the incident. He then submitted an incident report to the Port Authority. Over the following days, the harbour master made further inquiries into the circumstances of the incident, including reviewing the automatic identification system replay. The pilot was debriefed and consulted on a number of occasions. On 21 February, the harbour master notified Transport NSW, the state authority for transport services within New South Wales.

On 23 February, the harbour master contacted the ATSB and the Australian Maritime Safety Authority to discuss the incident. An incident report was submitted and, after obtaining further information, on 3 March the ATSB commenced this safety investigation into the incident.

On 12 March, while Aquadiva was at anchor off Map Ta Phut, an underwater inspection was conducted. No serious damage or definitive indication of grounding was discovered and only minor paint scratching and peeling was found.

Subsequent investigations by the Port of Newcastle included a hydrographic survey of the area of The Horseshoe. This survey indicated that Aquadiva had touched bottom although not enough for the ship to have stopped and grounded.

__________

- All times referred to in this report are local time, Australian Eastern Daylight Time (AEDT), Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) + 11 hours.

- All speeds used in this report are speed over the ground unless otherwise stated. One knot, or one nautical mile per hour equals 1.852 kilometres per hour.

- Wheel over point is the point at which the rudder angle is altered to start the turn to the next course allowing for distance and ship turning characteristics.

- The pilot also reported that the rate of turn indicator was digital rather than analogue, and that he had not seen this type of indicator before.

- Cardinal marks may be used to indicate that the deepest water in an area is on the named side of the buoy, indicate the safe side on which to pass or draw attention to a feature in the channel.

Personnel information

Pilot

The pilot had worked as a Newcastle harbour pilot for 22 years and completed almost 5,000 pilotages in and out of the port. He had also been a check pilot for 8 years.

The pilot was rostered off duty from 3 to 9 February 2017. He commenced a rostered duty period at 1600 on 10 February and completed two pilotages during that evening. He did not complete any pilotages on 11 February and Aquadiva was the pilot’s first pilotage for 12 February. He stated that he was well rested prior to boarding the ship at 2048.

Each pilot within the Port Authority of New South Wales (nsw) was subject to regular assessments by a check pilot, known as a ‘Pilots Annual Assessment’, while conducting an inbound or outbound pilotage. The pilot had completed an average of two checks per year during the period 2012 to 2016, with no problems noted on any of the checks. The last check was an outbound pilotage conducted on 18 October 2016.

In addition to the annual assessments, each pilot was required to undertake ‘electronic simulation’ training every 3 years. This involved conducting multiple simulated pilotage exercises over 3 days into and out of Newcastle. The scenarios included emergency and contingency situations, with the level of intensity higher than for most real world pilotages. Performance during the simulations was not recorded using a specific type of assessment form. However, if a pilot did not meet the required pilotage criteria, they were debriefed and the exercise conducted again until they were able to demonstrate the required proficiency. The pilot completed his last electronic simulation training in March 2016, and no problems were recorded on the pilot’s file.

The pilot was 58 years old. In accordance with the NSW Marine Pilotage Code, the Port Authority of NSW required each pilot to undergo regular health assessments conducted by an authorised health professional. For a pilot aged between 50 and 60, the code required an assessment to be conducted every 2 years. The pilot was undertaking annual medical assessments, with the last assessment conducted on 10 March 2016. The Port Authority advised that the pilot had been declared fit for work in each assessment during the 5 years prior to the 12 February 2017 occurrence, and no concerns had been reported about his medical fitness or performance during this period.

Following the occurrence, and with the pilot’s agreement, the pilot undertook a triggered medical assessment at the request of the Port Authority of NSW.[6] As part of this process, he undertook a neurological assessment. The assessment identified evidence of subtle difficulties with some cognitive abilities relative to other cognitive abilities, and recommended that further assessment be done in a simulated work environment. This assessment was not conducted. Following an extended period away from work, a subsequent medical assessment concluded that the stress resulting from the occurrence compromised the pilot's ability to safely return to pilotage work.

Overall, the ATSB concluded there was insufficient evidence to conclude that the pilot was experiencing a significant medical or physiological problem at the time of the occurrence that was associated with the occurrence.

Aquadiva crew

Aquadiva had a crew of 20 Greek, Filipino and Romanian nationals. The master had a Greek master’s certificate and had sailed as master since 2003. He had joined the ship 8 months prior to the incident. This was his first visit to Newcastle.

Vessel information

Aquadiva was registered in Greece, operated by Carras (Hellas), owned by Arion Shipping (Panama) and classed with the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS).

The ship is 292.0 m long with a beam of 44.98 m and has a summer deadweight capacity of 182,060 t at a draught of 18.30 m. Propulsion is via a Doosan MAN B&W 6S70 main engine delivering 18,660 kW via a right hand, fixed pitch propeller at 91 rpm. According to the ship’s posted manoeuvring characteristics, dead slow ahead (25 rpm) yielded 4.1 knots in the loaded condition and the minimum speed to maintain course was 3 knots.

Master-pilot information exchange

The pilot’s passage plan for the outbound pilotage was the same as that included on the port’s passage plan chartlets. The chartlets, which included waypoints and cross track errors, were available through the Port Authority of NSW website. The same chartlets were also used by the pilot that conducted the inbound pilotage of Aquadiva on 11 February 2017.

During the master-pilot information exchange (MPX) soon after the pilot boarded for the outbound pilotage, the ship’s master and pilot discussed the ship’s passage plan, the pilot card (appendix B), the Newcastle standard master/pilot information exchange document (appendix C) and the Newcastle pilot passage plans (appendix D).

The ship’s route and speeds down the channel were discussed as per the port passage plans. However, the pilot and master did not compare the ship’s passage plan with the pilot’s plan. There were some differences in the number and location of waypoints between the two plans (Figure 7), and these differences were not identified and corrected. In addition, the MPX did not include details of the passage such as manoeuvres through turns, wheel over points, rates of turn, comfort zones and cross track error.

The ship’s under keel clearance was also discussed. Based upon ship, tide and channel information, the static under keel clearance would be 1.6 m to contend with a vessel squat of about 0.6 m at 6 knots and the high tide (due at 2250) of 1.56 m. The MPX form noted that the wind was 20 knots from the south-south-east.

The MPX form also included additional general pilotage information. This included referring to the Port of Newcastle passage plan chartlets, details of several bridge team requirements,[7] guidance on reducing bridge alarms, pilot disembarkation details and anchor requirements. The master signed the MPX form acknowledging that he had received and understood the information provided, including the passage plan chartlets.

The pilot advised the ATSB that marine pilotage is a specialised skill requiring local knowledge and experience combined with complex, often interrelated, ship-specific and external variables. How an individual pilot conducts a pilotage also varies depending upon the situation at the time and as the pilotage progresses. He therefore noted that it is often difficult to clearly convey to the ship’s master in the timeframe available at the MPX all the information about how a specific pilotage will be conducted.

The pilot also advised that, in his experience, most ships did not input the port passage plan waypoints into their navigation systems prior to the pilot boarding, and the plans that were inputted generally contained fewer waypoints than the port’s plan.

Portable pilotage unit

A portable pilotage unit (PPU) is a portable, computer-based system that pilots bring aboard a vessel to use as a decision-support tool for navigating in confined waters (International Maritime Pilots’ Association). The units carried by Newcastle pilots operated independently of the ship’s equipment. These PPUs provided real-time automated positioning information which vastly enhanced situational awareness through the display of past tracks and predicted ship path on a chart familiar to pilots.

The Port of Newcastle Pilot Portable Units Operational Guidelines identified the PPU ‘as a decision support tool, to aid navigation and conning of the ship in confined waters.’

This equipment could also have been used as a communication tool, to assist in explaining the pilot’s passage plan and intended actions into and through the turn. In this way it could have assisted in building a shared mental model and clarifying the differences between the pilot’s and the ship’s passage plans.

The port’s operational guidelines also noted that since late 2012 the use of PPUs had become accepted practice on the majority of passages in the Port of Newcastle. This document went on to state that the harbour master had determined that a PPU was to be carried on passages involving vessels of 289 m length overall (LOA) and above, entering or departing the port.

Aquadiva is 292 m LOA. However, the pilot of the outbound pilotage did not take a PPU with him. He stated that, in discussion with the pilot of FPMC B Justice (which departed just prior to Aquadiva), they considered the conditions were such that visibility would not be restricted and that it was a good opportunity to practise and maintain visual pilotage skills. He also said that his understanding was that carriage of a PPU was not mandatory.

__________

- In addition to aspects of the occurrence, the medical personnel involved in conducting the assessment were also provided with information from the harbour master relating to concern about some aspects of the pilot’s behaviour during his last electronic simulator training (in March 2016). This concern was not recorded or discussed with the pilot at the time. The Port Authority subsequently advised the ATSB that the pilot’s reported behaviour during the simulator session did not appear to be unusual, given the context and nature of the simulator sessions being conducted.

- These requirements were extracted from Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA), 2016, Marine Notice 11/2016 Bridge Resource Management (BRM) and Expected Actions of Bridge Teams in Australian Pilotage Waters, AMSA, Canberra.

Introduction

As Aquadiva was piloted down the Steelworks Channel (Figure 6), the ship was close to the middle of the channel, as per the pilot’s and ship’s passage plans. However, as the ship approached the course alteration to port, insufficient rudder was applied to achieve the necessary rate of turn to successfully make the turn. The pilot was distracted and the ship moved sideways (slewed), wide into the turn, south of the intended route and toward the outer limits of the channel. At 2224, the ship had slowed to 2.6 knots and was atop the deep water channel 15.2 m contour, at risk of grounding. With the assistance of additional tugs, the ship’s sideways movement was controlled and it was subsequently returned to the channel and the intended route.

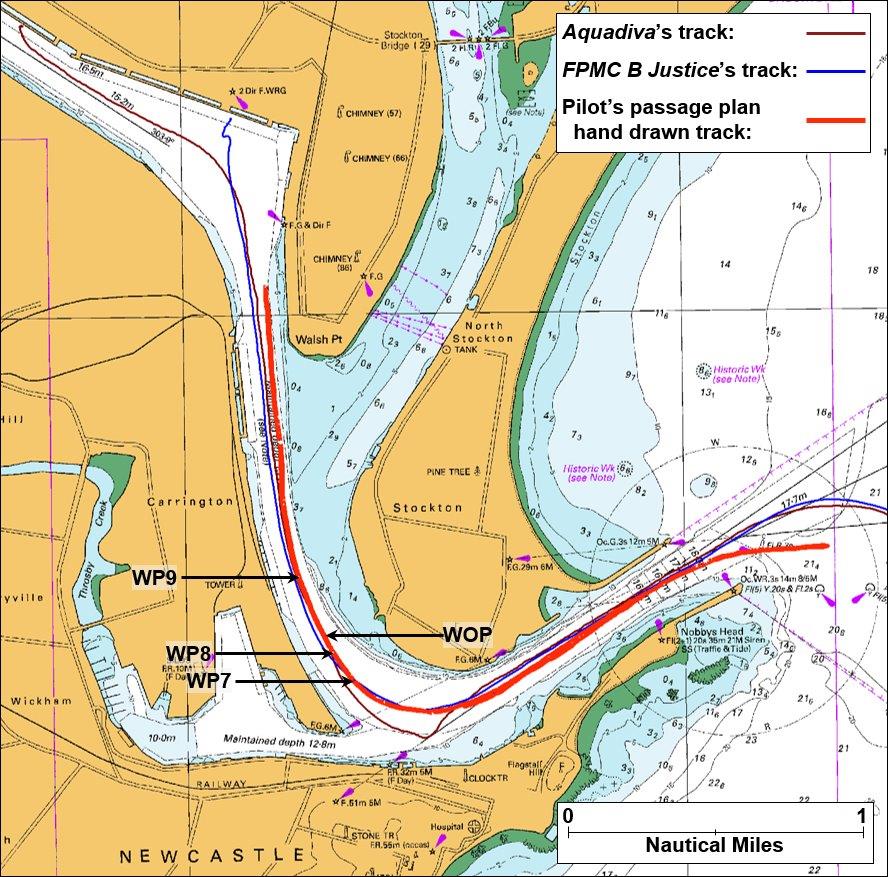

Figure 6: Extract from navigational chart Aus 207 showing a comparison between ship tracks and the pilot’s passage plan track

Source: Australian Hydrographic Service; annotations by ATSB

This analysis discusses the manoeuvring of Aquadiva through The Horse Shoe and then examines the turn in the context of the use of the available resources to monitor and manage the pilotage. The requirement to report incidents and the ambiguities around these requirements, by the relevant responsible persons, are discussed in relation to pilotage incidents and the effect on safety investigations.

Turning through The Horseshoe

Aquadiva’s pilot intended to follow the port’s passage plan (appendix D), passing through the waypoints. The ship passed through waypoints 9 and 8 as it approached the wheel over point (WOP) for the course alteration through The Horse Shoe (Figure 7). At this point, it was the pilot’s usual practice to apply sufficient rudder to get the ship to turn at about 2½ times the ship’s speed (about 13°/minute). On this occasion, the ship did not turn as expected and the pilot stated that his attention was focussed on the ship’s rate of turn indicator. Shortly after, as the ship passed to the west of WP7, it was turning, but not quickly enough to complete the turn.

The ship continued to turn too slowly despite the application of full port rudder. However, by the time the pilot looked outside the bridge and noticed this, the ship was already significantly off course. At 2225, the ship was about 1 cable (185 m) south of waypoint 5, in a position over the outer limits of the 15.2 m channel, possibly touching bottom.

Figure 7: Extract from navigational chart Aus 208 showing comparison of tracks and waypoints through The Horseshoe

Source: Australian Hydrographic Service; annotations by ATSB

Source: Australian Hydrographic Service; annotations by ATSB

In comparison, FPMC B Justice had taken the turn through The Horse Shoe about 15 minutes before Aquadiva. Its pilot had applied rudder to commence the turn at WP9, about 3 cables before WP8. The ship began turning and, as it passed Aquadiva’s WOP, its rate of turn was greater than 10°/minute and the turn was under control. Figure 7 shows that the ship then tracked close to or through the remaining waypoints in completing the turn. A rate of turn of 19°/minute was achieved between waypoints 6 and 5.

This comparison shows that not enough rudder angle was applied, early enough, to get Aquadiva to turn sufficiently quickly to make the turn. In the critical early stages of the turn, the pilot was distracted from the primary task of monitoring and controlling the turn. This distraction was for a sufficient amount of time for control of the turn to be lost. The situation was not identified and challenged by the ship’s crew.

Through a fortunate coincidence, the tugs returning from the successful departure of FPMC B Justice were nearby and able to lend assistance to Aquadiva. Their assistance aided in preventing the ship from grounding on the southern side of The Horse Shoe.

Situational awareness and shared mental models

Situational awareness can be defined as knowing what is going on around you. In relation to a ship’s passage, it includes knowing what has recently happened (perception), what is currently happening (comprehension) and, based on where the ship is, what is about to happen (projection).

Closely related to situational awareness is the concept of a shared mental model. Each individual member of a group performing a common task will develop a mental model of what they think will occur during the task. Each person’s mental model is based upon the information available to them at the time and their past experience. Ensuring that each member involved in a pilotage (pilot and ship’s bridge team) shares the same mental model of the voyage (passage and pilotage plan) is central to effective bridge resource management (BRM).[8]

Australian Marine Notice 17/2014[9] states that with a pilot embarked:

The bridge team should support the pilot by:

- maintaining a good lookout and situational awareness…

- continually monitoring the pilot’s actions and promptly seeking clarification as necessary…

- discussing, agreeing and communicating to the entire bridge team, any change to the ship’s voyage plan advised by the pilot…

To emphasise this, the Newcastle master-pilot information exchange (MPX) form contained guidance taken from Australian Marine Notice 11/2016[10] with respect to the ship’s bridge team, including the need to:

- clearly define and delegate tasks and responsibilities

- set and constantly review priorities

- continuously monitor the ship’s position, speed and heading

- continuously monitor the ship’s navigation against the passage plan and notify the pilot and master should any deviation from the plan or standard operating procedures occur.

The marine notice also stated:

The agreed passage plan, its understanding and the establishment of a ‘shared mental model’ by the entire bridge team forms the basis of a safe voyage under pilotage conditions…

It is essential that the pilot, master and bridge team work together to ensure that errors are detected early and corrected before the ship is put into any danger.

Furthermore, the Port of Newcastle’s pilotage safety guidelines[11] stated:

Efficient Pilotage is chiefly dependent upon the effectiveness of the communications and information exchanges between the pilot, master, bridge personnel and other participants including tug masters and mooring personnel. The mutual understanding each has for the functions and duties of the others is paramount. This is core to Bridge Resource Management and is a required element of the pilot’s task.

In summary, it can be stated that if there is no shared mental model for a complex task such as marine pilotage then BRM will be ineffective.

On board Aquadiva, the pilot had a plan for the pilotage and an intended route for the ship based on the port’s passage plan waypoints and his many years of experience of piloting similar sized ships out of the port. However, the pilot’s passage plan was not communicated to the ship until the pilot boarded and the MPX was conducted.

The ship also had a passage plan for the pilotage. However, the ship’s plan differed to the pilot’s in key areas, significantly in the region of the turn to port through The Horse Shoe (Figure 7). Here, the ship’s plan contained two less waypoints than the pilot’s plan. This meant that, though similar, the ship’s master and bridge crew built their mental model based upon differing information to the pilot. These differences were not identified, and corrected, during the MPX or at any time during the passage to The Horse Shoe.

The port’s passage plan chartlets, including waypoints and cross track errors, were available through the Port Authority of NSW website and they were also used by the pilot conducting the ship’s inbound pilotage. However, there was no procedure to proactively provide the passage plan to a ship prior to a pilotage and ensure that the ship’s crew had included it in the ship’s passage plan prior to the pilot boarding (for example, via inclusion in arrival requirements or through the ship’s agent). This contrasts with the procedure followed in a number of other ports around Australia and overseas, where the pilotage plan is proactively provided to the ship well prior to the arrival of the pilot on board. Such a process helps ensure the ship’s passage plan for the pilotage is the same as the pilot’s.

In Newcastle, the passive availability of the passage plan chartlets meant that it was not uncommon for ships arriving at the port to have not accessed this important information, despite opportunities to do so. On this occasion, had the pilot’s plan been received by the ship at an earlier stage (prior to passage), this plan, including transit parameters and limits, could have been included in the ship’s berth-to-berth passage plan. Any deviation from this plan could then have been explained during the MPX.

Furthermore, the pilot had not taken a portable pilotage unit (PPU) to assist with the pilotage. This equipment could also have been used as a communication tool, to assist in explaining the pilot’s passage plan and intended actions into and through the turn. In this way it could have assisted in building a shared mental model and clarifying the differences between the pilot’s and the ship’s passage plans.

In addition to differing passage plans and not fully explaining and communicating the intended plan, the pilot did not converse and engage frequently or effectively with the ship’s crew. At no time did the master or pilot seek to ensure that all personnel were actively engaged and shared the same detail for the pilotage, especially in the area of the turn to port. The pilot’s intentions were only broadly conveyed, such as the positioning and repositioning of the tugs and the hand drawn track on the passage plan chartlets. Details of the course alterations and any wheel over points, rates of turn, cross track limits or comfort zones were not discussed.

As a consequence of the differing mental models of the pilotage, the safety net around the pilotage, provided by BRM, was significantly compromised. The result was that specific details of how the pilotage was to progress resided only with the pilot, and the pilotage was then exposed to the dangers of single-person errors. As a consequence, the ship’s crew were unable to accurately and actively monitor the ship’s progress or the actions of the pilot against the pilot’s plan. They did not question, challenge or intervene, or otherwise effectively contribute to the safe completion of the pilotage. Any errors which arose, such as the ship not being in a position the pilot was comfortable with, or the rate of turn being too slow, were not identified as errors. Consequently, no action was taken to prevent these errors from escalating into the incident.

In summary, from the outset, neither the pilot nor the master took the opportunity to effectively manage the resources present and available to safely monitor the ship’s progress or the actions of other bridge personnel. Consequently, any opportunity to capture and correct errors which occurred was lost.

Previous incidents

A common thread in pilotage related investigations conducted by the ATSB has been the breakdown in BRM and its implementation. This is particularly apparent in establishing and maintaining a shared mental model for the entirety of the passage. A recent investigation involving contact between the bulk carrier Navios Northern Star and a navigation buoy while under coastal pilotage in the Prince of Wales Channel, Torres Strait, Queensland (ATSB investigation 325-MO-2016-003, report published June 2017) also highlighted these points.

That investigation found that:

- BRM techniques were not effectively followed by the ship’s bridge team. This meant that the ship’s personnel did not have the same mental model of the course alteration as the pilot and they did not actively monitor the pilot’s execution of the alteration.

- The ship’s voyage plan contained only basic passage information and its bridge team did not know or fully understand the pilot’s planned operational parameters and limits, including WOPs and safety margins.

- The pilot was distracted during a critical 2-minute period before the incident. Further, the master’s challenge to the pilot as the ship closed on the buoy was too late.

Similar conclusions were drawn in a recent grounding investigated by the UK Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB report number 23/2017 grounding of the ultra-large container vessel CMA CGM Vasco de Gama, Thorn Channel Southampton, report published October 2017).

Amongst other things, the MAIB investigation found:

These findings echo similar findings from many of the pilotage incidents the ATSB has investigated, including the current one.

- The rate of turn required to stay within the dredged channel could not be sustained.

- The pilotage was not properly planned with key decision points, WOPs and abort options not identified.

- The ship’s pilotage plan did not reflect the plan (intentions) of the lead pilot.

- Poor information exchange and communication led to the lead pilot and the bridge team not sharing the same mental model.

- Differing mental models meant that the ship’s master and bridge team were unable to monitor, challenge or seek to clarify the lead pilot’s actions and the vessel’s progress.

- The breakdown of BRM resulted in the lead pilot becoming the sole decision-maker and a single point of failure.

- Portable pilotage units were carried but were not effectively used to assist the master / pilot exchange and provide additional situational awareness.

Overall, these investigations highlight the changing requirements and expectations of industry and involved organisations with respect to pilotage. In particular, the desire to use BRM as an effective risk and error management tool is apparent. This is being achieved through emphasis on greater passage plan detail, improved communications, improving the building of a shared mental model and similar strategies.

For example, as a result of the Navios Northern Star investigation and as part of a continuous improvement program, the pilotage organisation involved undertook significant proactive safety action. This included initiating a pilotage workshop facilitated by an external consultant to assess and amend the company’s pilotage safety management system (SMS). Significantly, one aim was to determine and include good pilotage practice guidance in the SMS.

Importantly, the workshop determined that good pilotage practice covered all aspects of the pilotage, from booking to completion, not just the conduct of the ship. Amongst other initiatives, this resulted in the identification of practices and procedures to assist pilots to:

- Establish involvement in and agreement to BRM techniques as essential for safe conduction of any pilotage.

- Set operational parameters and limits for ship handling and navigation for each of the company’s pilotage areas.

- Ensure ships’ personnel have accurate detail of the passage plan the pilot will follow, well in advance of the pilotage. The crew are to be expected to incorporate this information, including transit parameters and limits, into the ship’s berth-to-berth passage plan. Any deviation from this plan is to be explained fully to the master during the MPX phase(s) of the pilotage.

- Assign roles and responsibilities to ships’ personnel in support of and as assistance to the pilot.

- Use a variety of techniques for engaging and informing ships’ personnel of the pilot’s plans and intentions, so as to establish and maintain a shared mental model and situational awareness. In doing so the ship’s crew can be actively involved and monitor the pilot and the passage and provide challenge/intervention as needed.

- Use the PPU not just as a significant navigation tool but as an information, teaching and communication tool for use with the ship’s master and crew. PPUs were identified as being especially useful for developing expectations and explaining impending manoeuvres such as turns and course changes.

Incident reporting

For all ships in Australian waters, the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) requires that it be notified within 4 hours of becoming aware of any incident that has affected, or is likely to affect the safety, operation, or seaworthiness of the vessel. The Transport Safety Investigation (TSI) Act 2003 requires a responsible person to report marine accidents and serious incidents to a nominated official as soon as possible. A responsible person is defined by the Transport Safety Investigation Regulations as the master or person in charge of the ship, the owner or operator of the ship, an agent of the owner or operator, or a pilot who has duties on board the ship.

On board Aquadiva, the master was not aware that the ship had contacted the bottom, or had come very close to grounding. He therefore did not report the incident to AMSA until prompted by notice from the ship’s Newcastle agent. The initial report from the master to AMSA was dated 14 February, 2 days after the incident. This report identified the incident as a ‘dangerous occurrence’ and detailed manoeuvring difficulties but did not mention grounding or touching bottom.

The pilot reported the incident to the Newcastle Harbour master and submitted a report to the Port Authority upon his return ashore from the pilotage. The pilot, in reporting the incident to port management, believed he had fulfilled his requirements to report. Some confusion then existed regarding the requirements for subsequent reporting to authorities by port officials not nominated as responsible persons in the legislation.

The combined delays in reporting this incident and initiating the safety investigation meant that valuable evidence available at the time of, and for a short time after, the incident was lost. This is particularly relevant to the voyage data recording information from the ship, which provides valuable, relevant data and recordings to assist in safety investigations. Further, once the safety investigation had commenced, sufficient time had passed to have potentially affected the memories of the people involved in the occurrence.

__________

- Bridge resource management, or BRM, can be defined as the effective management and use of all appropriate resources, including personnel and equipment, by a ship’s bridge team to complete its voyage safely and efficiently.

- Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA), 2014 Marine Notice 17/2014 Sound navigational practices, AMSA, Canberra.

- Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) 2016, Marine Notice 11/2016 Bridge Resource Management (BRM and Expected Actions of Bridge Teams in Australian Pilotage Waters, AMSA, Canberra.

- Port Authority of New South Wales, 2015, Marine Pilotage Safety Guidelines for the Port of Newcastle.

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the near grounding, under pilotage, of the bulk carrier Aquadiva in Newcastle on 12 February 2017. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

Contributing factors

- As Aquadiva commenced the 90° course alteration to port through The Horse Shoe, insufficient rudder was applied, and too late, to achieve the necessary rate of turn to successfully make the turn. As a consequence, the ship went off course, toward the southern limit of the channel, coming very close to grounding.

- During the early stages of the turn, the pilot was distracted from the primary task of monitoring and controlling the turn when he was likely focussed on the rate of turn indicator and achieving the desired rate of turn. This short period of time was for sufficient duration at a critical point in the turn that control of the turn was compromised.

- A shared mental model for the pilotage was not established between the pilot, Aquadiva’s master and the bridge crewmembers. In particular, techniques such as

- ensuring the same plan for the pilotage was shared by the ship’s crew and the pilot prior to the pilot boarding,

- utilising equipment such as the portable pilotage unit to assist explanation of the pilotage stages and parameters,

- ensuring active monitoring, challenge and response/intervention and error management techniques were used by all personnel involved in the pilotage, were not used. Therefore, bridge resource management was not effectively implemented and practised.

Other key findings

- Ambiguities and uncertainties around reporting requirements for port pilotage incidents led to delays in the ATSB being notified of the incident and commencing a safety investigation. These delays meant that volatile evidence such as the voyage data recordings were not able to be collected.

- The tugs returning from the successful departure of FPMC B Justice offered assistance to Aquadiva. Their assistance aided in preventing the ship from grounding.

Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence.

Port Authority of New South Wales

The Port Authority of New South Wales informed that ATSB that it had undertaken the following safety actions:

- an external law firm was engaged to conduct an investigation into the incident and report findings and provide recommendations

- Port Authority pilots, including those in ports other than Newcastle, were informed of the event and learnings from it

- procedures are to be amended to require compulsory carriage of portable pilotage units on all pilotages

- pilot passage plans have been located in a more prominent position on its website (since February 2017)

- a project to implement sharing of electronic passage plans has been commenced

- a training package for pilots informing them of their obligations and requirements to report incidents is to be developed and implemented.

Carras (Hellas), Aquadiva’s operator

Carras (Hellas) notified the ATSB that it had taken the following actions in response to this incident:

- conducted an internal investigation into the incident and distributed copies of the internal investigation report throughout the company’s fleet, with direction to masters to be aware of bridge resource management (BRM) procedures associated with pilotage plans and to discuss the incident during ship safety meetings

- discussed the incident, investigation and lessons learned during Aquadiva’s safety committee meeting following the incident and provided bridge resource management and safety of navigation training to Aquadiva’s bridge team officers

- discussed the incident, investigation and outcomes during a shore-based deck officers forum meeting attended by senior fleet deck officers.

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- Aquadiva’s master and bridge team members

- Carras (Hellas)

- the Port Authority of New South Wales - Port of Newcastle, harbour master, vessel traffic information centre and harbour pilots

- Svitzer Australia and tug masters

- the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA).

References

Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) 2016, Marine Notice 11/2016 Bridge Resource Management (BRM) and Expected Actions of Bridge Teams in Australian Pilotage Waters, AMSA, Canberra. Available at www.amsa.gov.au.

Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA), 2014, Marine Notice 17/2014 Sound navigational practices, AMSA, Canberra. Available at www.amsa.gov.au.

Clark, I.C. 2005, Ship Dynamics for Mariners, The Nautical Institute, London.

International Maritime Pilots' Association (IMPA), 2016, Guidelines on the design and use of Portable Pilot Units, IMPA, London. Available at www.impahq.org.

Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) 2017, Report on the investigation of the grounding of the ultra-large container vessel CMA CGM Vasco de Gama, Thorn Channel, Southampton, England, 22 August 2016, MAIB, Southampton. Available at www.gov.uk/maib.

Rowe, R.W. 1996, The Shiphandler’s Guide, The Nautical Institute, London.

The Nautical Institute 2016, ‘Error Management’, The Navigator, October 2016.

Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003. Available at www.legislation.gov.au.

Submissions

Under Part 4, Division 2 (Investigation Reports), Section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 (the Act), the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. Section 26 (1) (a) of the Act allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the Port Authority of New South Wales, Newcastle harbour master, Newcastle harbour pilot, the master and bridge team members on board Aquadiva, Carras (Hellas), the Australian Maritime Safety Authority, the Hellenic Bureau for Marine Casualties Investigation (HBMCI) and Svitzer Australia.

Submissions were received from the Newcastle harbour pilot, the master of Aquadiva, the Port Authority of New South Wales (including harbour master), Carras (Hellas) and the Australian Maritime Safety Authority. The submissions were reviewed and where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Appendix A – Table of selected data for Aquadiva’s departure from Newcastle

|

Time (LT)[12] __________ |

Telegraph |

SOG[13] __________ |

COG[14] __________ |

HDG[15] __________ |

Comment |

|

21:23 |

DSAhd SlowAhd |

0.1 |

228 |

124 |

Depart berth |

|

21:34 |

DSAhd |

2.7 |

121 |

120 |

Pass K5 |

|

21:43 |

2.6 |

116 |

125 |

Turning into Steelworks Channel |

|

|

22:04 |

SlowAhd |

2.7 |

175 |

175 |

Pass D4-D5, Kooragang Is and Stockton Channel |

|

22:14 |

HalfAhd |

3.9 |

168 |

162 |

Pass WP9, ME to half ahead |

|

22:15 |

4.2 |

163 |

158 |

||

|

22:16 |

4.6 |

157 |

154 |

||

|

22:17 |

4.9 |

153 |

153 |

WOP at about 22:17:45 |

|

|

22:18 |

5.1 |

154 |

153 |

Pass WP8 at about 22:18:30 |

|

|

22:19 |

5.1 |

159 |

147 |

Pass about 70 m to west of WP7 at 22:19:45 |

|

|

22:20 |

5.1 |

150 |

134 |

Pass about 160 m west of WP6 at 22:20:45 |

|

|

22:21 |

5.0 |

138 |

123 |

Pass about 400 m west of WP5 at 22:21:45 |

|

|

22:22 |

SlowAhd DSAhd STOP DSAst SlowAst |

4.7 |

130 |

109 |

Pass about 140 m south of WP6 at 22:22:15 Telegraph orders all recorded in this minute |

|

22:23 |

HalfAst FullAst HalfAst SlowAst DSAst STOP DSAhd |

3.6 |

114 |

97 |

|

|

22:24 |

2.6 |

105 |

87 |

||

|

22:25 |

SlowAhd HalfAhd |

2.1 |

113 |

68 |

Most southerly point |

|

22:26 |

1.7 |

81 |

51 |

Pass about 140 m south of WP5 at 22:26:45 |

|

|

22:27 |

1.9 |

42 |

49 |

||

|

22:28 |

2.4 |

34 |

55 |

Additional tugs released |

|

|

22:29 |

2.7 |

47 |

58 |

||

|

22:30 |

3.0 |

52 |

58 |

||

|

22:31 |

3.2 |

53 |

59 |

||

|

22:32 |

3.4 |

59 |

60 |

Pass about 65 m north of WP4 at 22:32:30 |

|

|

22:33 |

3.6 |

62 |

59 |

||

|

22:34 |

Full Ahd |

3.9 |

57 |

59 |

|

|

22:35 |

4.2 |

60 |

58 |

Appendix B – Aquadiva’s pilot card and master / pilot information exchange form for departure Newcastle

Source: Master, Aquadiva

Source: Master, Aquadiva

Appendix C – Master / pilot information exchange (MPX) document, pilot’s component

Source: Port Authority of New South Wales

Appendix D – Reproduction of the pilot’s Newcastle pilot passage plan chartlets showing the planned track and speeds

These chartlets, including the waypoint and cross track error lists, were available on the Port Authority of New South Wales’ website, Port Authority NSW under Newcastle Harbour). Pilots conducting inbound pilotages also used the same documents.

Source: Port Authority of New South Wales

Source: Port Authority of New South Wales

__________

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationRReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2018

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

Ship details

|

Name: |

Aquadiva |

|

IMO number: |

9469675 |

|

Call sign: |

SVAN4 |

|

Flag: |

Greece |

|

Classification society: |

American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) |

|

Ship type: |

Bulk carrier |

|

Builder: |

Odense steel shipyard (Denmark) |

|

Year built: |

2010 |

|

Owner(s): |

Arion Shipping (Panama) |

|

Manager: |

Carras (Hellas) (Greece) |

|

Gross tonnage: |

93,360 |

|

Deadweight (summer): |

182,060 t |

|

Summer draught: |

18.30 m |

|

Length overall: |

292 m |

|

Moulded breadth: |

44.98 m |

|

Moulded depth: |

24.85 m |

|

Main engine(s): |

Doosan-MAN B&W 6s70 C-7 |

|

Total power: |

18,660 kW at 91 rpm |

|

Speed: |

15.0 knots |

|

Damage: |

Nil reported |