What happened

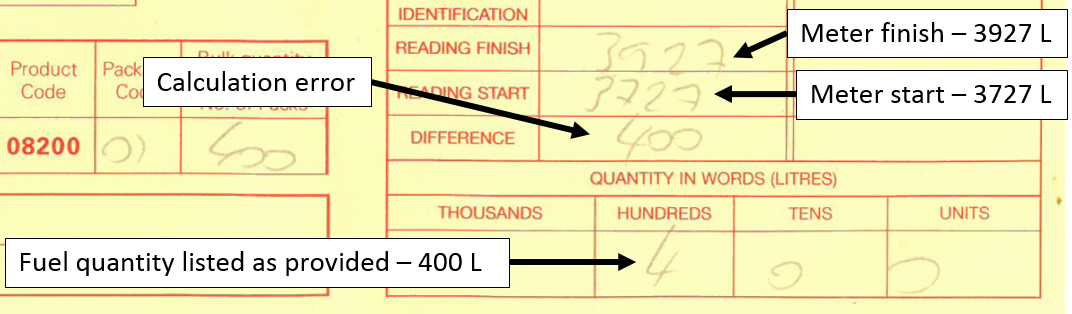

On the morning of 15 June 2017, the pilot of a Beech 58 aircraft, registered VH-PBU, operated by Savannah Aviation, contacted a refueller at Mount Isa Airport, Queensland (Qld) and requested 400 L of fuel be added to the aircraft. The pilot then left the airport and was not present for the refuelling. The refueller attended the aircraft and provided 200 L of fuel. After the refuelling, the refueller completed a fuel delivery receipt (Figure 1). On this delivery receipt the refueller recorded fuel meter readings starting at 3,727 L and finishing at 3,927 L, a difference of 200 L. The refueller recorded the amount provided as 400 L and placed a copy of the delivery receipt through an aircraft window. The refueller then left the aircraft prior to the pilot returning.

After returning to the airport, the pilot of the aircraft collected the fuel delivery receipt and noted 400 L as the quantity listed. However, the pilot did not cross-check the meter readings recorded on the delivery receipt to verify the amount provided. The pilot recorded 400 L of fuel being added in the aircraft fuel log and calculated the total fuel on board to be 570 L. The pilot then cross-checked the fuel added by observing that the fuel gauges had risen since the last flight. The combined fuel capacity of the aircrafts main tanks was 628 L. The pilot then completed two short flights.

Figure 1: Extract of fuel delivery receipt

Source: Queensland Police Service

At the end of the day, the refueller totalled the daily fuel delivery quantities and detected a 200 L discrepancy between the recorded deliveries and the meter readings. The refueller identified that the discrepancy was due to an error in the refuelling of VH-PBU. The refueller immediately went to the aircraft to notify the pilot of the error, however the refueller was not able to locate the pilot. The refueller was then distracted by a phone call and forgot about the refuelling error.

On 19 June, the aircraft was ferried from Mount Isa to Burketown Airport, Qld.

On 20 June, a second pilot conducted a passenger charter flight in the aircraft from Burketown. As this pilot prepared to depart on this flight, a passenger commented on the low fuel level indicated on the aircraft fuel gauges. The pilot reviewed the fuel log which showed 332 L on board. The pilot then cross checked the fuel log calculations against the fuel gauges and was satisfied that the calculations were correct. After the flight, this pilot contacted the pilot who had organised the previous refuelling to confirm that the amount of fuel on board the aircraft was consistent with that in the fuel log. The refuelling pilot confirmed that the amount should be correct. The second pilot conducted three more flights that day. After the second flight, a further 100 L of fuel was added to the aircraft.

On the morning of 26 June 2017, the second pilot prepared to conduct a ferry flight in the aircraft from Burketown to Normanton Airport, Qld. The pilot checked the fuel log which showed 248 L to be on board the aircraft. At about 0815 Eastern Standard Time (EST), the flight departed Burketown, the pilot was the only person on board. The take-off and climb were uneventful.

About 10 NM north of Normanton, the aircraft descended through about 3,500 ft above mean sea level. At this time, the right engine began to surge and the pilot observed fluctuations in fuel flow for the right engine. The pilot selected the right engine low pressure fuel boost pump to on, however, the surging continued. The pilot then used the fuel selector to cross-feed fuel from the left fuel tank to the right engine. After selecting cross-feed from the left main tank, the surging stopped and the right engine resumed normal operation.

About 20 to 30 seconds after selecting cross-feed, both engines began surging. The pilot selected the high-pressure fuel boost pumps on for both engines, selected mixture to full rich, advanced the propeller control and advanced the throttles. As the aircraft descended through about 2,000 ft, the engines continued surging. About 20 to 30 seconds later, both engines failed.

After the engines failed, the pilot feathered[1] both propellers. The pilot determined that the aircraft had insufficient energy to glide to Normanton Airport and selected a clear paddock as suitable for a forced landing. The pilot observed a powerline on the southern boundary of the paddock and left the landing gear retracted until they were assured the aircraft would clear the powerline.

After determining that the aircraft would clear the powerline, the pilot lowered the landing gear and landed in the field. During the landing roll the aircraft impacted a number of bushes.

The pilot was not injured during the incident, however, the aircraft sustained substantial damage (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Damage to right wing

Source: Queensland Police Service, annotated by ATSB

Operator refuelling procedure

The operator’s operations manual contained the following guidance on recording fuel uplift following refuelling:

The crew member supervising refuelling is to note the fuel meter readings before and after fuel delivery and confirm that the correct amount is entered on the fuel record.

Beech 58 fuel system and management

Accurate fuel determination

Due to the design of the main fuel tanks, unless the tanks were full, it was not possible to determine fuel quantity in each tank by visual inspection or through the use of a dipstick. The exact quantity of fuel on board could only be determined when the tanks were filled. Fuel quantity was therefore estimated through the use of a fuel log.

Fuel usage calculations

The operator specified a cruise fuel flow rate of 128 L/hr for the aircraft, a cruise-climb fuel flow rate of 160 L/hr and an allowance of 10 L for engine start and taxi. Company pilots used these figures to calculate the amount of fuel used during flight and deducted this amount from the fuel on board at the start of the flight to calculate current fuel on board. After refuelling, the amount uplifted was added to the fuel log prior to the next flight.

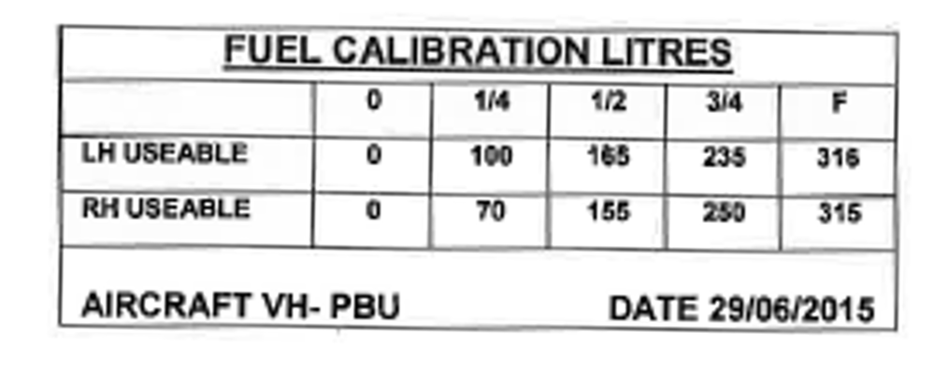

Fuel calibration card

The pilots crossed-checked the fuel log against the aircraft fuel gauges to determine the accuracy of the fuel log calculations. To assist with this check, the aircraft had a fuel calibration card. The data for this card is compiled during maintenance, the aircraft is fuelled with known amounts and these amounts are checked against the aircraft gauge readings in order to calibrate the gauges. The results are recorded on the card. The fuel calibration card is mounted on the instrument panel immediately adjacent to the fuel gauges.

Figure 3: VH-PBU fuel calibration card

Source: Operator

The Beech 58 also provides external fuel gauges for the main tanks mounted on the wings. The use of these gauges is not specified in the operations manual. Company pilots did not use the external fuel gauges to verify fuel log calculations.

Guidelines for aircraft fuel requirements

The Civil Aviation Safety Authority advisory publication, CAAP 234-1(1): Guidelines for aircraft fuel requirements, provides the following guidance for fuel quantity cross-checking:

Unless assured that the aircraft tanks are completely full, or a totally reliable and accurately graduated dipstick, sight gauge, drip gauge or tank tab reading can be done, the pilot should endeavour to use the best available fuel quantity cross-check prior to starting. The cross-check should consist of establishing fuel on board by at least two different methods.

Refuelling pilot comments

The pilot who requested the refuelling on 15 June provided the following comments:

- It would be beneficial to be present when the aircraft is being refuelled. In addition, more diligence should be taken to cross-check the meter readings when reviewing the fuel delivery receipt.

- There were opportunities over the days following the refuelling error for the error to be communicated, however, this did not occur.

- The fuel gauges in the aircraft generally showed an indication of full when the aircraft was loaded with more than three-quarters of tank capacity. After the refuelling on 15 June, the gauges indicated about three-quarters full, therefore the refuelling pilot believed the amount of fuel on board matched the amount calculated in the fuel log.

Forced landing pilot comments

The pilot who was in command of the aircraft at the time of the forced landing provided the following comments:

- The normal method of verifying the accuracy of the fuel log was to cross-check against the fuel gauges. The only other way to accurately determine the fuel on board was to completely fill the main fuel tanks. The operator had no set schedule for filling the main fuel tanks to verify the accuracy of the fuel log. Filling the tanks to full only occurred when required by flight planning requirements.

- Prior to the incident flight, the fuel gauges indicated about a quarter full. The pilot calculated that the flight from Burketown to Normanton would use about 80 L of fuel.

- In normal operations, the right main fuel tank fed fuel to the right engine and the left main fuel tank fed fuel to the left engine.

- The company operated a number of Beech 58 aircraft. The fuel indication calibrations were different in each aircraft. The pilot had not flown PBU regularly, and therefore was not familiar with the fuel gauge readings expected for different fuel loads in this aircraft. The aircraft contained a fuel gauge calibration card (Figure 3) which was only a general guide as to the fuel quantity indication.

Previous occurrence

A review of the ATSB database identified a previous fuel related event involving a Beech 58 aircraft: Fuel related event involving Beech BE58, VH-ECL, 111 km E of Tindal Aerodrome, NT on 14 August 2013. The incident is summarised below:

ATSB investigation AO-2013-131

On 14 August 2013, the pilot of a Beech BE58 aircraft, registered VH‑ECL, was preparing for a charter flight from Tindal to the Borroloola aeroplane landing area, Northern Territory.

Using the operator’s elected fuel flow rate for the aircraft of 125 L/hr, the pilot calculated that a minimum of 545 L of fuel was required. The pilot elected to carry 570 L. In preparation for the flight, the pilot referenced the fuel log, which indicated that about 267 L of fuel was on board the aircraft. Consequently, the pilot refuelled the aircraft, adding about 153 L into each of the main fuel tanks.

During the cruise, the pilot observed the fuel quantity gauge for the right main fuel tank reading zero, but the fuel flow, and engine temperature and pressure indications were normal. The aircraft landed at Borroloola and the passengers disembarked. The pilot re‑checked the fuel calculations and determined that there was sufficient fuel on board for the return trip. The pilot noted that the right fuel quantity gauge was still reading zero and the fuel quantity gauge for the left main tank was indicating about three-quarters full.

On the return flight, when about 50-60 NM from Tindal, the right fuel flow gauge dropped to zero. The pilot shut down the right engine, notified air traffic control and conducted a single-engine landing at Tindal.

This incident highlighted the importance of establishing known fuel status regularly and the need to use multiple sources to determine fuel quantity. This is particularly important for determining accurate fuel flow rate calculations and when the fuel quantity on board can only be accurately determined when the fuel tanks are full.

Safety analysis

On 15 June 2017, the aircraft was refuelled with 200 L of fuel, however, 400 L was recorded as being delivered. The pilot did not detect the discrepancy in the fuel delivery receipt and added 400 L to the aircraft fuel log.

The refuelling procedures did not require a cross-check to verify the amount of fuel provided and the error was not detected by the refueller until the end of the day. While an attempt to communicate this error was made, ultimately it was not communicated to the pilot or the operator.

Over the next 11 days, the aircraft completed a number of flights operated by both pilots without the discrepancy between the calculated and actual fuel on board being detected.

Prior to the flight on 26 June, the fuel log showed the aircraft as having 248 L on board. The pilot verified this value using the aircraft fuel gauges which indicated the tanks were about one quarter full. At this time, the actual fuel on board would have been about 48 L. The fuel calibration card indicated that for a reading of about one quarter full, the actual fuel on board should be 170 L. This indication corresponds more closely to the calculated fuel on board (248 L) than the actual amount of fuel likely to have been on board the aircraft at that time (48 L) and may have reinforced the pilot’s assumption that the fuel log calculation was correct.

The aircraft departed Burketown with insufficient fuel to complete the flight to Normanton. As the aircraft descended towards Normanton, the quantity of fuel in the right main tank was exhausted and the right engine began to fail. The pilot was able to keep the engine running momentarily by cross-feeding fuel from the left main tank. Shortly after selecting cross-feed, the quantity of fuel in the left main tank was also exhausted and both engines failed.

Findings

These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

- The refueller recorded 400 L on the fuel delivery receipt when only 200 L had been provided. The refuelling procedures did not contain a cross-check to verify the amount of fuel provided and this error was only detected by the refueller at a later stage. The error was not communicated.

- The refuelling pilot did not detect the discrepancy in the fuel delivery receipt and recorded an incorrect amount of 400 L added fuel in the fuel log. Over subsequent flights the discrepancy between the calculated and actual fuel on board was not detected by either pilot.

- The engines failed due to fuel exhaustion.

Safety action

Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence.

Fuel provider

As a result of this occurrence, the fuel provider has advised the ATSB that they are taking the following safety action:

Change to procedure

- The fuel delivery procedure has been amended so that pilots must now review and sign the fuel delivery receipt after receiving fuel.

Safety message

This incident underlines the importance of communication once an error has been discovered. The refuelling error was discovered 11 days prior to the incident flight, however, this was not communicated to the operator or pilots. Knowledge of the error would have enabled the pilots to correct the fuel log and avoid the incident.

Accurate fuel management is critical to the safe operation of an aircraft. The ATSB publication Avoidable Accidents No. 5 - Starved and exhausted: Fuel management aviation accidents provides the following key messages:

Accurate fuel management starts with knowing exactly how much fuel is being carried at the commencement of a flight. This is easy to know if the aircraft tanks are full or filled to tabs. If the tanks are not filled to a known setting, then a different approach is needed to determine an accurate quantity of usable fuel.

Accurate fuel management also relies on a method of knowing how much fuel is being consumed. Many variables can influence the fuel flow, such as changed power settings, the use of non-standard fuel leaning techniques, or flying at different cruise levels to those planned. If they are not considered and appropriately managed, then the pilot’s awareness of the remaining usable fuel may be diminished.

Keeping fuel supplied to the engines during flight relies on the pilot’s knowledge of the aircraft’s fuel supply system and being familiar and proficient in its use. Adhering to procedures, maintaining a record of the fuel selections during flight, and ensuring the appropriate tank selections are made before descending towards your destination will lessen the likelihood of fuel starvation at what may be a critical stage of the flight.

Aviation Short Investigations Bulletin - Issue 62

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2017

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________