What happened

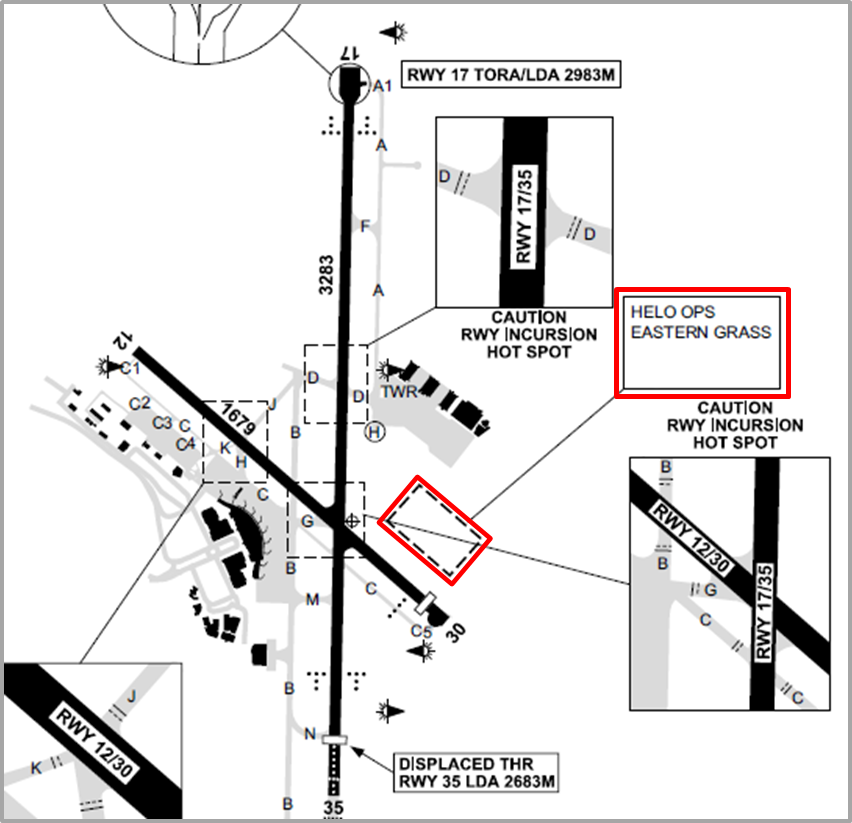

At about 0747 Eastern Standard Time[1] on 2 June 2017, a Robinson R44 II helicopter, registered VH-FOA (FOA) commenced taxiing at Canberra Airport, Australian Capital Territory. The helicopter was preparing for a training flight in the circuit area. A student pilot and instructor were on board the helicopter. The crew of FOA planned to conduct circuit operations on the eastern grass parallel to runway 12/30 (Figure 1).

Canberra Airport was a controlled airport and classified as Class C airspace.[2] Air traffic control (ATC) was providing an aerodrome control service from the Canberra tower. There were two controllers in the tower: a surface movement controller (SMC) and an aerodrome controller (ADC).

Figure 1: Diagram of Canberra Airport showing eastern grass helicopter operations

Source: Airservices Australia, annotated by the ATSB

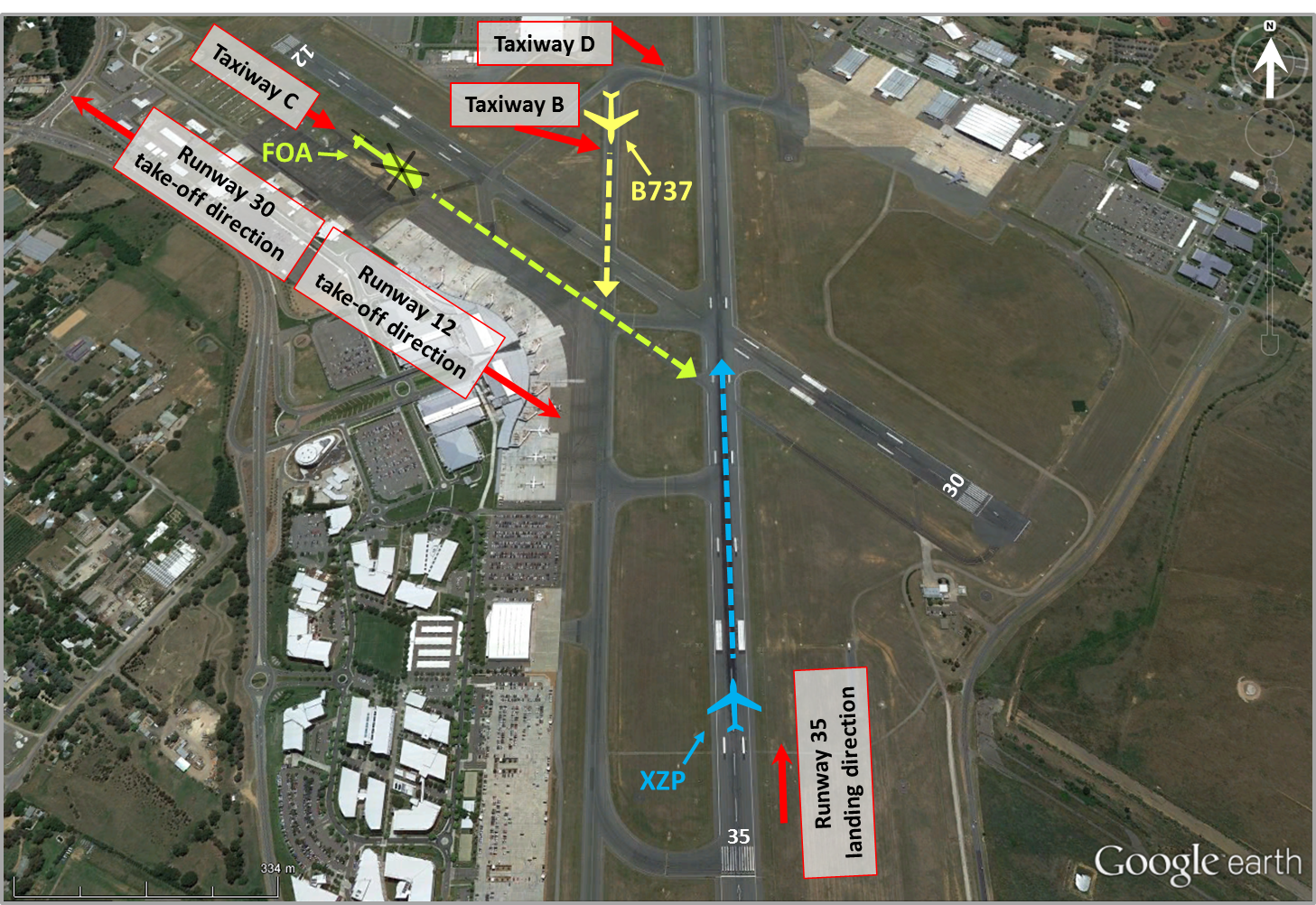

The SMC issued a taxi clearance for FOA to taxi from the general aviation apron to taxiway C (Figure 2). The SMC also advised FOA’s crew to expect to depart from taxiway C in the runway 30 direction.

At about 0749, the SMC cleared a recently landed Boeing 737 (B737) on taxiway B to cross runway 30 southwards.

At about 0750, the ADC cleared a Boeing 737-838, registered VH-XZP (XZP), to land on runway 35 (Figure 2). The aircraft was a scheduled passenger flight from Melbourne, Victoria. At this time, FOA’s crew were on the surface movement control frequency, hence unaware of XZP’s landing clearance.

Figure 2: Canberra Airport and projected routes of the aircraft involved in the incident

Source: Google earth, annotated by the ATSB

Shortly after, FOA was lined up on taxiway C in the runway 30 direction and the student pilot informed the ADC that it was ready for departure. The taxiing B737 was still on taxiway B and on the surface movement control frequency, and XZP was about to land.

The ADC sighted FOA before issuing a take-off clearance to depart parallel to runway 12 and to maintain the runway heading. The student pilot read back this instruction to depart parallel to runway 12 and then realigned FOA in that take-off 12 direction (Figure 2). The student and instructor checked the airport windsocks – there was no downwind component in the take-off direction. Soon after, FOA began departing along taxiway C in the runway 12 direction.

After issuing FOA with a take-off clearance, the ADC initiated coordination with the approach controller (located at the ATC Melbourne centre) about a potential change of the duty runway from runway 35 to 17. This coordination became his priority as he needed to issue clearances to arriving aircraft that would use the changed runway. While conducting the coordination, the ADC was also assessing the weather conditions to the north of the airport, and scanning runway 35 prior to XZP crossing the threshold. His focus remained on those tasks – he did not observe FOA departing.

Both the instructor and student pilot of the departing FOA sighted the taxiing B737 to the left of the helicopter on taxiway B. The instructor was surprised ATC had not provided any information about the taxiing B737. The helicopter was about 200 ft above ground level (AGL), and in order to avoid overflying the taxiing aircraft that had started to cross taxiway C, FOA was manoeuvred slightly to the right of taxiway C’s centreline. After passing taxiway B and the B737, FOA returned to the centreline of taxiway C and continued on the cleared departure path.

Initially, the airport terminal buildings obscured the view that FOA’s crew had of the approach to runway 35 (see Figure 2). Once runway 35 came into view, and before crossing the runway, the crew looked to ensure there was no conflicting traffic. They then saw XZP touch down on the runway ahead of the helicopter.

At about 0751, the instructor informed the ADC of the proximity event FOA had had with XZP. The ADC then realised that FOA was departing in a different direction to what he had intended. He instructed FOA to maintain runway heading and issued it a wake turbulence caution. Then, at about 0753, he instructed FOA to track for the eastern grass before acknowledging that an incorrect take-off clearance instruction had been issued.

The helicopter and XZP continued their operations without further incident.

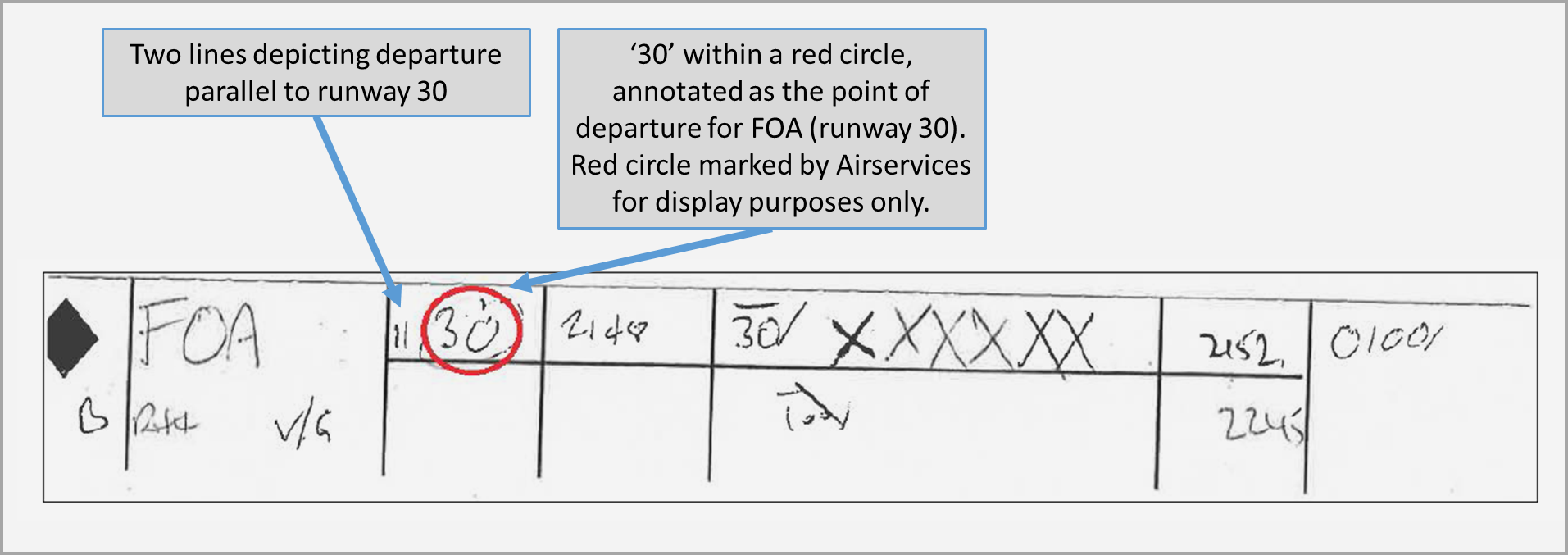

Flight progress strips

At the Canberra tower, controllers use flight progress strips to assist maintain situational awareness of ATC operations and traffic. The controllers use standard annotations on flight progress strips in accordance with ATC procedures. One of these annotations is recording the departure runway/location.

In the case of FOA, the departure location was recorded as two vertical lines followed by 30, indicating a departure parallel to runway 30 (Figure 3). As runway 30 was not the duty runway (which was runway 35) at the time, its designator was circled in red (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Flight progress strip for FOA

Source: Airservices Australia, annotated by the ATSB

When a controller’s instructions to an aircraft are acknowledged, the controller can use the progress strip to check the information is correct. The controller then may (but is not required to) annotate that on the progress strip next to the information. However, when the ADC issued FOA a take-off clearance, he did not refer to the progress strip or annotate it.

Safety analysis

The ADC issued a take-off clearance to FOA that was contrary to his intended separation plan. The intended plan was for FOA to take-off in the runway 30 direction while the instruction given was to take-off in the runway 12 direction (the opposite direction). This error was not detected by the ADC or anyone else, until after FOA’s vigilant crew saw XZP touching down ahead of the helicopter and the instructor reported the event to ATC. In part, the error was a result of the ADC becoming preoccupied with coordination tasks with the approach controller immediately after he issued FOA the take-off clearance.

However, some existing risk controls could have allowed early detection of the error. The ADC’s intended plan was indicated on the flight progress strip but he did not refer to the progress strip. The student pilot read back the take-off clearance issued but the ADC did not notice that the clearance issued was not what he had intended. As he was not annotating the strip as a matter of course either, he did not have another cue or memory prompt to avoid the error or detect the error once it had been made. While the ADC should have been visually observing FOA departing, he did not because he became focused on the coordination tasks.

Airservices Australia advised that they had ‘classified the occurrence as an information error, not a loss of separation after determining that the error had occurred in the execution of an appropriate plan. It was also determined that the disposition of traffic, assured separation, including wake turbulence.’

This occurrence involved one aircraft being inadvertently cleared to depart along a flight path that crossed an active runway (and the associated go-around flight path) in use by a landing aircraft. Consequently, the ATSB assessed that the departing FOA encountered a loss of runway separation assurance with the arriving XZP. It was also determined that there was a conflict between FOA and the taxiing B737. While the timing of events and the location of the aircraft involved meant no significant manoeuvring was required by FOA’s crew, the consequences could have been severe had the sequence of events been slightly different.

Findings

These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

- The aerodrome controller (ADC) made an error when issuing the take-off clearance to VH‑FOA. He instructed the helicopter to depart parallel to runway 12, in the opposite direction to his intended instruction of departing parallel to runway 30.

- The ADC became preoccupied with runway coordination tasks immediately after issuing the incorrect take-off clearance and, hence, did not detect the error.

- The ADC had not taken up the option of annotating the flight progress strips to check and confirm instructions given, which may have helped avoid the error or its earlier detection.

Safety message

This occurrence highlights the importance of air traffic controllers using system support tools effectively to manage the operational environment. The use of flight progress strips is intended to enhance the situational awareness of controllers. When fully utilised, these tools are an effective monitoring support tool. Flight progress strips also provide information to assist with the correct execution of the controller’s plan and the early detection of any errors that may occur.

In a complex and dynamic air traffic control environment, it is important that all people working in that environment remain vigilant, maintain open communications, and use the available systems and tools to minimise the risk of errors.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2018

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________

- Eastern Standard Time (EST): Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) + 10 hours.

- Class C is the controlled airspace surrounding major airports. Both IFR and VFR flights are permitted and must communicate with air traffic control. IFR aircraft are positively separated from both IFR and VFR aircraft. VFR aircraft are provided traffic information on other VFR aircraft.