What happened

On the afternoon of 30 March 2017, the flight crew of a British Aerospace Jetstream 3206 aircraft, registered VH-OTE, prepared to conduct Pelican Airlines flight FP314 from Canberra Airport, Australian Capital Territory, to Newcastle Airport (Williamtown), New South Wales. The flight crew comprised the captain and the first officer.

All pre-flight checks, taxi and engine run-ups were normal, however the left engine single red line computer was unserviceable (see Single red line section below). This did not prevent the aircraft from operating the flight but meant that the flight crew had to set the power of the engine using the manufacturer’s documented torque tables.

At about 1545 Eastern Daylight-saving Time,[1] the aircraft departed from runway 17 at Canberra Airport. As the aircraft passed about 7,000 ft on climb, the flight crew observed that the right engine was producing about 40 per cent torque, while the left was producing about 65 per cent torque. Fuel flow to the right engine and exhaust gas temperature (EGT) were also slightly lower than the left. The captain tried to use the power lever to increase torque to the right engine but it did not respond to produce greater than 40 per cent.

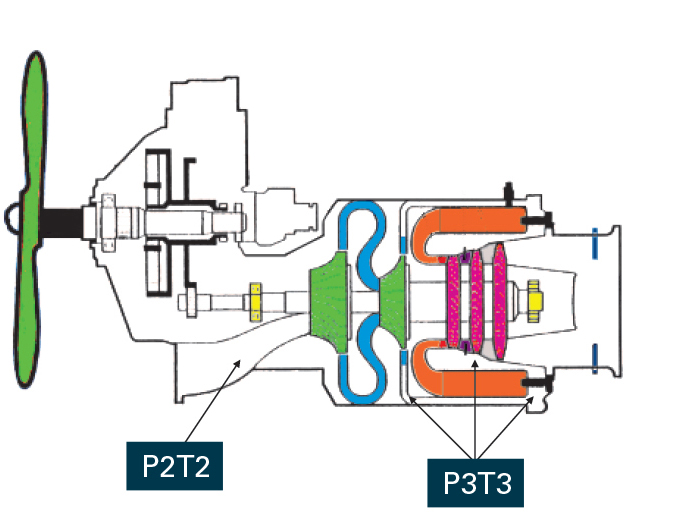

The first officer retrieved the appropriate section of the quick reference handbook (QRH), which they then actioned. The most common cause of low torque was icing on the compressor inlet pressure (P2T2) sensors (Figure 1). The QRH response was to turn on heat to melt the ice and wait 5 minutes to see if there was a power response.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of Garrett TPE331 engine showing P2T2 inlet

Source: FAAsafety.gov, modified by the ATSB

After completing the actions and waiting the prescribed 5 minutes, there was still no positive response in the right engine to moving the power lever so the crew elected to return to Canberra Airport. At about 1559, passing about 9,000 ft, the first officer advised air traffic control (ATC) that they intended to return to Canberra and ATC provided a clearance for their approach.

About 5 minutes later, as the crew prepared for the approach to return, normal power returned to the right engine. Both engines were now responding to power lever inputs over the full range. Hence, the flight crew assessed that icing had been the cause of low torque and it had taken longer than 5 minutes for the ice to melt and the engine to respond.

At about 1604, when at about 9,000 ft, the first officer advised ATC that they had rectified the situation. The first officer advised that they intended to continue to Newcastle, and subsequently obtained a clearance to reroute.

Less than 2 minutes after turning the aircraft to track towards Newcastle, the right engine issue recurred. The captain verified that they could not get more than 40 per cent torque but that by pulling the power lever back, they could get flight idle torque. In those circumstances, the flight crew elected to return to Canberra but not to shut down the right engine.

The flight crew did not declare an emergency,[2] conducted a normal approach and, at about 1621, the aircraft landed on runway 17 at Canberra Airport without further incident.

Analysis

Flight crew assessment of issue

The aircraft was approaching freezing levels, with the outside temperature about 5 °C at the time the right engine torque decreased. The aircraft was not in visible moisture but there were showers in the area. The captain thought at the time that due to the venturi effect (lowering the temperature of the air flowing into the engine inlets), it could have been the start of freezing conditions for the engine and that they would have been turning on the anti-icing before long. The captain assessed that it was therefore possible that the P2T2 (and P3T3) inlets had frozen over and caused the reduction in available power.

Once the flight crew had turned the anti-icing system on (in accordance with the QRH checklist), they left it on. Therefore, when the problem recurred, they concluded that icing was not the cause.

Decision to return

The crew assessed that the engine was producing enough torque to operate the aircraft safely. As holding fuel was required in Newcastle and the cloud base was down to the minima specified for the approach, however, they elected to return to Canberra. There were no handling issues with the aircraft, and no adverse yaw. The crew assessed that with 40 per cent torque on the right engine, they could probably still cruise at the planned altitude of FL 150. [3]

During the descent, in accordance with normal procedures, the flight crew reduced the torque on both engines to 40 per cent, then 20 per cent on final approach and 12 per cent for landing. As they were able to reduce power on the right engine, the approach was therefore conducted without any asymmetric thrust.

Single red line

The single red line (SRL) simplifies how the pilot sets the engine torque. The SRL computer calculates the temperature difference between the turbine inlet temperature and exhaust gas temperature based on variables including pressure, altitude and true airspeed.

Without the SRL functioning, the flight crew use the manufacturer’s torque tables to determine the required values and, importantly, to ensure maximum EGT is not exceeded. The flight crew also used trend monitoring data (available in the cockpit) to see the relative torque and maximum EGT for each engine.

During the occurrence flight, the flight crew of VH-OTE were monitoring the EGT closely. According to the captain, the SRLs in the J3206 aircraft malfunctioned quite frequently but were readily rectified by maintenance engineers.

Weather

The captain reported that although there were some showers in Canberra at the time, the weather was ‘not too bad’. In Newcastle, however, there were severe storms, strong rain and winds, and the visibility and cloud were down to the approach minima. There was up to 60 minutes of holding fuel required in Newcastle due to the weather.

Engineering report

After the incident, aircraft maintenance engineers conducted ground runs of the engine. The engineers found no defects with the anti-ice valve, and the torque signal conditioner was normal. The engineers increased the maximum fuel flow setting on the fuel control unit (FCU) by 10 kg per hour and subsequent ground runs were satisfactory.

The aircraft subsequently operated several sectors with both engines operating normally. Three days later, the aircraft underwent scheduled maintenance. The maintenance engineers found that the No. 2 (right) engine FCU P3 piston was leaking into the P2 section. The P3-P2 is a dry section of the FCU so that any leaks are air-to-air.

The FCU was sent to an engine overhaul facility in the United States for further inspection. The FCU had accumulated 2,504.87 hours since new and had run for 1,713.97 hours while installed on VH-OTE. The inspection found corrosion on the P3 piston sleeve, which was replaced, along with a new piston seal and ring as part of the standard overhaul process.

The P3 air pressure positions the fuel metering valve to ensure the correct fuel to flow ratio. The facility engineers advised that an unresponsive power lever was not a normal result of a P3 piston seal leakage. The most frequent fault reported for P3 piston seal leakage was high flight idle fuel flows, which did not occur in this case.

The facility engineers had previously advised the aircraft operator that the engine inlet P2T2 sensor was known to be a possible cause of a non-responsive power lever and lack of control of engine power. An inspection of the sensor was carried out but no defect was found.

The FCU and P2T2 sensor were replaced and the issue did not recur.

Engine manufacturer comments

Honeywell advised that leakage of the FCU P3 piston into the P2 section can result in the inability of the FCU to reach the max fuel schedule. The symptoms of this condition would be similar to icing of the P2 inlet due to the increased pressure within the P2 section.

Threat and error management

When the problem occurred, the captain asked the first officer to retrieve the QRH. The first officer then read the relevant section and together the flight crew completed the actions. When the problem was not resolved after the prescribed 5-minute period, the flight crew discussed their options. They assessed that the weather in Newcastle was unacceptable, particularly with the possibility of having to conduct a missed approach if they were unable to get the required visibility at the minima. Therefore, the flight crew decided to return to Canberra Airport.

The flight crew also discussed the possibility of having to conduct a go-around. They assessed that a go-around with 40 per cent torque on the right engine was possible, that they would have been able to manage the asymmetric thrust, and that they would have been able to remain visual in the Canberra circuit area. There was a greater likelihood of having to go around at Newcastle due to weather, which reaffirmed their decision to return to Canberra.

Previous incident

The ATSB investigated an in-flight engine shutdown involving Pelican Airlines British Aerospace Jetstream 32 aircraft, registered VH-OTQ, that occurred in December 2016 (AO-2016-171). Shortly after the aircraft reached its cruising altitude, the right engine EGT gauge indicated a higher temperature than normal. The power lever did not respond to pilot inputs.

In accordance with the QRH, the flight crew shut down the right engine and returned to Newcastle Airport, New South Wales, from where they had departed. The flight crew did not declare a PAN, but the controller initiated an alert phase[4] during the aircraft’s approach.

In that incident, the fuel control unit’s bearing cage was broken, with many small fragments found to be interfering with the unit’s operation. The bearing cage held the bearing balls and kept them separated from each other.

Findings

These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

- During climb, the right engine was limited to a reduced torque value and the engine did not respond to the pilot’s power lever inputs to increase torque. Due to this reduced torque and poor weather conditions in Newcastle, the flight crew elected to return to Canberra.

- The reduced engine torque was consistent with leakage of the fuel control unit P3 piston into the P2 section.

- The flight crew used effective communication and threat and error management techniques in responding to the issue. Although making an urgency (PAN) broadcast would certainly have appropriately alerted air traffic control (ATC) to the situation, the flight crew did not consider a PAN broadcast was necessary in this case as they had advised ATC of the reduced engine torque, and because a normal approach was possible.

Safety message

This incident provides a good example of effective threat and error management techniques. The flight crew were faced with an abnormal situation and made the decision to turn back to Canberra in a collaborative way.

It is important to broadcast a PAN or MAYDAY call, as appropriate, when time permits to alert air traffic control to an emergency situation. In response, air traffic controllers will provide assistance such as a priority landing to allow an aircraft to land as soon as possible. Airservices Australia publications In-flight emergencies and What happens when I declare an emergency provide relevant information.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2018

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________

- Eastern Daylightsaving Time (EDT): Universal Coordinated Time (UTC) + 11 hours.

- Airservices Australia defines the two levels of emergency notifications as MAYDAY: My aircraft and its occupants are threatened by grave and imminent danger and/or I require immediate assistance; PAN PAN: I have an urgent message to transmit concerning the safety of my aircraft or other vehicle or of some person on board or within sight but I do not require immediate assistance.

- Flight level: at altitudes above 10,000 ft in Australia, an aircraft’s height above mean sea level is referred to as a flight level (FL). FL 150 equates to 15,000 ft.

- Alert Phase (ALERFA): an emergency phase declared by the air traffic services when apprehension exists as to the safety of the aircraft and its occupants.