What happened

On 13 March 2017, at about 1700 Eastern Standard Time (EST), a de Havilland DHC-2 seaplane, registered VH-AWD, taxied at Hardy Lagoon aircraft landing area (ALA), for a charter flight to Shute Harbour, Queensland. On board the aircraft were the pilot and five passengers.

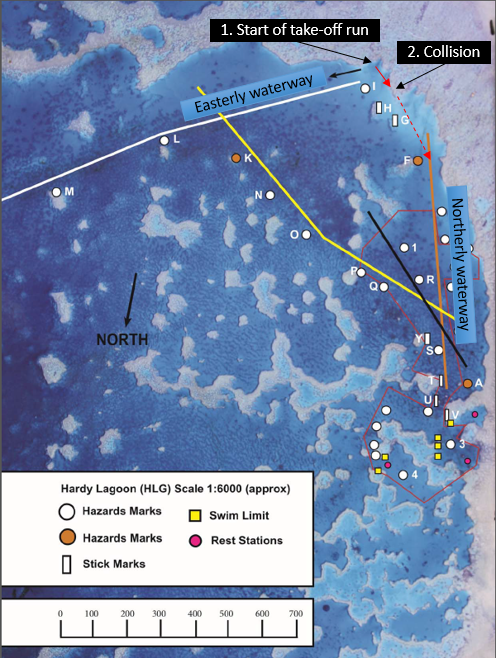

Hardy Lagoon had four waterways, marked by buoys, for take-off and landing. The company preference for take-off was to use the most into wind waterway. The wind strength was about 8 kt with a low sun, calm to smooth water surface and low tide at 0.6 m. The pilot positioned the aircraft between the northerly and easterly waterways (Figure 1) and started the engine with the water rudders retracted to allow the aircraft to weathercock into wind.

The wind effect on the aircraft indicated to the pilot that the northerly waterway was the most into wind waterway. In order to maximise the take-off distance available the pilot applied power to start the take-off run from a position to the south-east of the northerly waterway, while aiming to join the waterway at buoy F (Figure 1). Shortly after applying full power, and before the aircraft entered the northerly waterway, both floats struck submerged reef, which brought the aircraft to a stop.

Figure 1: Hardy Lagoon (north pointing downwards)

Source: Operator, annotated by ATSB (black, yellow, white and orange lines indicate the dimensions of the waterways)

The pilot shut down the aircraft and assessed the passengers for injuries and the aircraft for damage. The passengers were uninjured, and the aircraft was stuck on the reef at the point of low tide. After relaying a message to their[1] company, via an airborne helicopter, the pilot elected to transfer the passengers to one of the boats used for reef tours in Hardy Lagoon. About 20 minutes after transferring the passengers to the boat, another company aircraft arrived and was able to return the passengers to Shute Harbour before last light.

The following day the aircraft sank in 3 m depth of water after several attempts were made to keep it afloat. The aircraft was subsequently salvaged.

Seaplane take-off

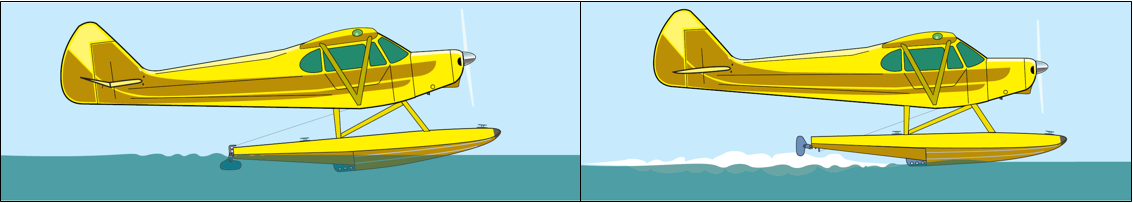

The application of power to start the take-off pushes the centre of buoyancy aft, due to increased hydrodynamic pressure on the bottom of the floats. This places more of the seaplane’s weight towards the rear of the floats which sink deeper into the water. This results in a higher nose attitude, reduced forward visibility, and creates high drag, which requires large amounts of power for a modest gain in speed (Figure 2 left). This phase of the take-off is known as in the plow.

As speed increases, hydrodynamic lift on the floats and the aerodynamic lift of the wings supports the seaplane’s weight instead of the buoyancy of the floats. This allows the pilot to lower the nose attitude, which raises the rear portions of the floats clear of the water (Figure 2 right). This is the planing position, which reduces water drag and permits the seaplane to accelerate to lift-off speed. The pilot reported this was about 25-30 kt for the DHC-2.

For further information about seaplane operations, see the United States Federal Aviation Administration handbook: Seaplane, skiplane, and float/ski equipped helicopter operations handbook.

Figure 2: Seaplane in the plow (left) and planing (right)

Source: US Federal Aviation Administration

Environmental conditions

The tide was at 0.6 m at the time of the collision, which occurred outside of the waterways. When the tide is above 2.5 m, the aircraft can manoeuvre around Hardy Lagoon outside of the dimensions of the ALA without striking reef. Below the 2.5 m tidemark, it was known that the reef could be struck when manoeuvring the aircraft outside the dimensions of the ALA. However, the pilot believed that their chosen track from buoy I to buoy F, where they would join the northerly waterway, was clear of underwater terrain. There were no hazard marks on the left side of their track towards buoy F, but this was outside the prescribed waterway.

The collision occurred at 1700 and sunset was about 1820, with the associated low sun angle. When the sun angle is low, more light is reflected off the water than refracted through the water and consequently it is more difficult to see objects underneath the surface.

The pilot described the water conditions in the lagoon as smooth to calm. Prior to the accident, and while still on the boat, the pilot received a phone call from the chief pilot to check on conditions. This was in response to light winds affecting an earlier take-off. They both agreed that with an eight-knot northerly wind, take-off could be achieved without the need to reduce weight.

Recent experience

The pilot had extensive flying experience, which included 127 total landings on and take-offs from Hardy Lagoon, 17 under supervision. They had operated at Hardy Lagoon the previous day. At the time of the collision, they were in their ninth-hour of their duty for the day. Earlier in the day, they experienced two unsuccessful take-off attempts in which the aircraft did not get into a planing position, which they attributed to light winds and high aircraft weight.

Safety and survivability

The pilot received annual training from the operator in emergency and life-saving equipment and passenger control in emergencies, in accordance with Civil Aviation Order 20.11. Prior to flight, passengers receive a video briefing on the safety aspects of the aircraft and are required to wear life jackets for the flights. A personal locator beacon and first aid box are carried on board the aircraft.

Search and rescue time (SARTIME) is managed by the operator. On approach to Hardy Lagoon, by about 500 ft above sea level, the pilots notify their operator of their arrival, at which point the operator starts a SARTIME for the aircraft’s departure from Hardy Lagoon of arrival time plus 2.5 hours. The operator has two boats moored at Hardy Lagoon with a mobile phone capable of contacting the mainland.

Previous similar accidents

On 25 June 2015 a de Havilland Canada DHC-2, registered VH-AWI, struck reef while attempting to take-off from Hardy Lagoon. While attempting a take-off manoeuvre to maximise the take-off distance available, the aircraft inadvertently drifted out of the waterway and struck reef.

For further information refer to ATSB report AO-2015-069.

Safety analysis

At the time that the pilot attempted the accident take-off, they had experienced two failed take-off attempts earlier in the day, which they believed were the result of light wind and high aircraft weight. As the wind was still light and the aircraft was relatively heavy, the pilot decided to start the take-off from a position outside the dimensions of the waterway, to increase the take-off distance available.

At the time of the attempted take-off, the tide was close to the low point, but the reef struck by the aircraft was still submerged. The sun angle was low, which increased the amount of sunlight reflected from the water surface. At the speed of the collision, the aircraft nose attitude was at the highest angle for the take-off run, which combined with the sunlight reflection to severely restrict the pilot’s ability to detect submerged reef.

Findings

These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

- The light wind conditions and aircraft weight led the pilot to initiate the take-off run from outside of the dimensions of the waterway in order to maximise the take-off distance available.

- The aircraft struck submerged reef, which was obscured by the sunlight conditions and high nose attitude of the aircraft, before it entered the waterway.

Safety message

The pilot commented that there were a number of factors, specific to their own operation, which could minimise the risk of a similar occurrence. They noted there are too many variables in the operation to identify all possible scenarios when in training. Their most important lesson was the need to ask ‘am I safe’, particularly in ambiguous conditions, and ‘if I continue on this plan, will I remain safe?’

Part of Aviation Short Investigations Bulletin - Issue 60

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2017

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________

- Gender-free plural pronouns: may be used throughout the report to refer to an individual (i.e. they, them and their).