What happened

On 20 January 2017, a British Aerospace AVRO 146-RJ85, registered VH-NJW, conducted a charter flight from Perth to Darlot, Western Australia (WA). There were four crew and 58 passengers on board the aircraft. The captain was the pilot flying (PF), seated in the left seat, and the first officer was the pilot monitoring (PM), seated in the right seat.[1]

The aircraft departed from Perth Airport at about 0630 Western Standard Time (WST) and tracked towards Darlot. Prior to the top of descent, the flight crew obtained the local weather from Leinster Airport, situated about 28 NM (52 km) from Darlot. The Leinster aerodrome weather information service (AWIS)[2] indicated a strong easterly wind, so the PF positioned the aircraft to join a 5 NM (9.3 km) straight-in approach to runway 14.

Darlot Airport had an unsealed runway with no electronic approach path guidance with a published RNAV-Z (GNSS) runway 14 approach. The procedure for the crew to monitor their descent profile was to crosscheck the distance and altitude information from the published approach chart, which provides a 3° descent on final approach. Three white cones, located on the left and right side of the runway strip and 300 m in from the runway threshold, provided the pilot with their visual aiming point markers for the landing. Therefore, on short final, the PF would change their flight path guidance cue from distance and altitude to the aiming point markers for the aircraft landing.

When the aircraft joined the final approach leg, the PF noticed dust in the vicinity of the runway and commented to the PM that there could be a vehicle on the runway. At about 2.5 NM (4.6 km) from the runway, the PF concluded the dust was not from a vehicle and that it was a line of dust from the strong easterly wind, which extended the length of the runway strip,[3] on the southern side of the runway. At about the same time, the PF visually identified the runway[4] markers.[5] On short final, the PF transitioned from the distance-altitude information to the aiming point markers located on the left side of the runway strip.

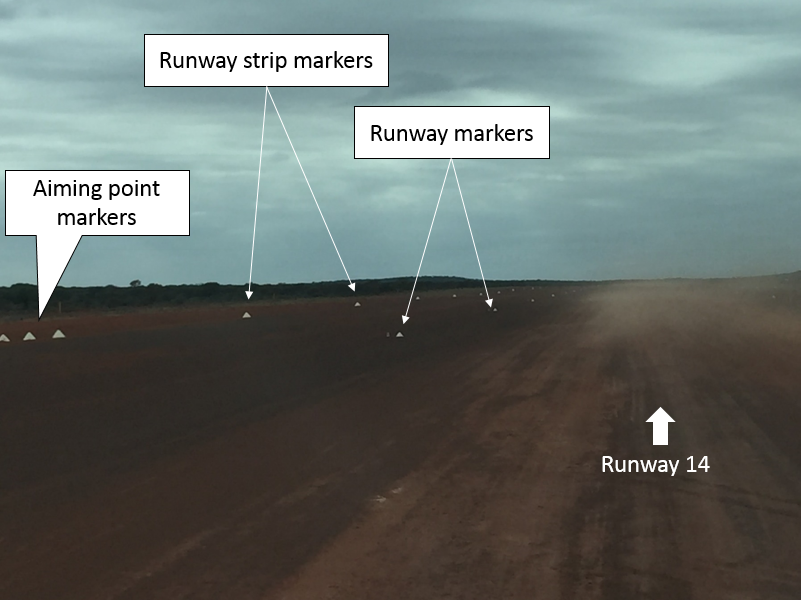

The aircraft landed without incident. However, as the aircraft slowed to taxi speed, the PF observed cones and runway lights on the right side of the aircraft, but only cones on the left side of the aircraft. The PF then noticed that the raised dust on the right side of the runway strip covered both the runway markers and runway strip (Figure 1). They had landed the aircraft on the graded area of the runway strip to the left of the runway. The PF manoeuvred the aircraft back onto the runway, taxied to the apron and shutdown without further incident. The aircraft was not damaged.

Figure 1: Darlot Airport runway 14

Source: Pilot, annotated by ATSB. Image depicts Darlot Airport runway 14 and left side of runway strip as viewed from the right seat of the aircraft with white frangible cones used as markers. Raised dust extends from the centre of the runway across the southern side of the runway strip.

Aerodrome markers

The Manual of Standards (MOS) Part 139 – Aerodromes, provided the standard for aerodrome markers. In accordance with MOS 139 paragraph 8.2.1.1, ‘markers must be lightweight and frangible; either cones or gables.’

Runway markers

Darlot Airport used identical white frangible cones as markers for both the runway and the runway strip. The runway was 30 m wide and 1,969 m long. The runway strip was 90 m wide. Therefore, the lateral spacing of the cones for the runway and the runway strip either side of the runway were equidistant.

Aiming point markers

In accordance with MOS 139 paragraph 8.3.7, on sealed runways, aiming point markers are conspicuous stripes painted on the runway surface. If a visual approach slope indicator system (VASIS) is used, then the VASIS is located within the runway strip and the beginning of the aiming point marking must coincide with the origin of the visual approach slope.

Where aiming point markers are not required, such as on unsealed runways, the airport operator can elect to ‘implement an aiming point marking by providing an appropriate marking.’ Darlot Airport used three frangible white cones, either side of the runway on the edge of the runway strip, as aiming point markers (Figure 1).

Objects on runway strips

MOS 139 paragraph 6.2.24 stated ‘A runway strip must be free of fixed objects, other than visual aids for the guidance of aircraft or vehicles. All fixed objects permitted on the runway strip must be of low mass and frangibly mounted.’

Location of aiming point markers

The aircraft operator provided services to three other airports with unsealed runways. Following this incident, the operator reviewed the other airports and found that at two airports the aiming point markers were located inside the runway strip (one used gable markers and the other cones), either side of the runway (Figure 2), and at the third airport the aiming point markers had been removed. Therefore, the aiming point markings were inconsistent between all four airports.

Figure 2: Gable aiming point markers within the runway strip (different airport used by the operator)

Source: Aircraft operator

In 2015, the Darlot Airport operator consulted with the Civil Aviation Safety Authority about the position of the aiming point markers. It was determined that they were not standard markings. Therefore, the airport operator could request a dispensation from MOS 139 to place them in the runway strip next to the runway, or alternatively, place the markers outside the runway strip without a dispensation. The airport operator passed this information on to the aircraft operator, and it was agreed to place them outside the runway strip, in lieu of requesting a dispensation.

Visual illusions

According to the Flight Safety Foundation, visual illusions occur ‘when conditions modify the pilot’s perception of the environment relative to his or her expectations, possibly resulting in spatial disorientation or landing errors.’ The key factors and conditions which result in visual illusions are the airport environment, runway environment and weather conditions.

Further information on visual illusions is available from the Flight Safety Foundation approach-and-landing accident reduction tool kit Briefing Note 5.3 - visual illusions.

Safety analysis

The PF advised that the final approach to land at Darlot, was a period of high workload because the aircraft was flown manually with cross-checks of distance and altitude used to manage the descent profile. On the incident flight, the PF’s attention was initially captured by raised dust, which indicated to the PF that there could be a vehicle on the runway. About halfway down the final approach, the PF discounted the presence of a vehicle, but then incorrectly identified the left runway strip markers as the left runway markers because the right runway and runway strip markers were obscured by the raised dust. This was confirmed in their mind by the presence of the aiming point markers on the left side of the runway strip. The PF was seated in the left seat and therefore used the aiming point markers on the left side as their visual guidance cue for the aircraft landing.

The siting of aiming point markers at airports with unsealed runways used by the aircraft operator was not standardised with respect to the type of markers used or the position of the markers relative to the runway. The pilot had experience, from operating into other unsealed runways, of aiming point markers positioned in the runway strip next to the runway. Therefore, the position of the aiming point markers on the left side of the runway strip markers was not recognised by the PF as an indicator that the aircraft was landing to the left of the runway.

ATSB comment

On approach to land, the PF must scan between the near end and far end of the runway for their visual judgement of flare height and alignment of the aircraft with the runway centreline. A greater amount of visual processing is dedicated to the central region of the retina (fovea) than to the peripheral regions of the retina. Consequently, central portions of a visual image are seen to a higher resolution than peripheral portions.

For a pilot focused on the runway centreline, the aiming point markers will move from central vision to peripheral vision at three times the distance for markers laterally displaced 45 m in lieu of 15 m from the runway centreline.

The ATSB notes that the aiming point markers are a visual guidance cue for the PF. Increasing the lateral displacement of the markers from the runway may divert the PF’s scan further from the runway centreline at a critical stage of flight.

Findings

These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

- The PF landed the aircraft in the runway strip to the left of the runway due to raised dust obscuring the markers on the right side of the runway and runway strip.

- Aiming point markers were employed in a non-standard manner at the unsealed runways used by the operator, which may have contributed to the PF landing the aircraft left of the runway.

Safety action

Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence.

Operator

As a result of this occurrence, the aircraft operator has advised the ATSB that they have taken the following safety actions:

Internal investigation and review

The operator has conducted their own internal investigation of the incident, which included a review of the unsealed runways they operate the AVRO 146 into.

Discussion paper

The operator submitted a discussion paper to the Civil Aviation Safety Authority on the provision of aiming point markers for unsealed runways. The paper proposes the standardisation of aiming point markers in accordance with the system previously tested by the United States Federal Aviation Administration.

The results of the testing can be found in ‘Marking and Lighting of Unpaved Runways – Inservice Testing’: DOT/FAA/CT-84/11.

Safety message

Following the incident, the pilot reported that, in hindsight, the raised dust they observed on the runway strip should have led to a go-around manoeuvre, but their visual cues led them to believe they were aligned to land on the runway. The Flight Safety Foundation briefing note 5.3 provides strategies for pilots and operators to mitigate the risk of a visual illusion incident during approach and landing.

Part of Aviation Short Investigations Bulletin - Issue 60

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2017

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________

- Pilot Flying (PF) and Pilot Monitoring (PM): procedurally assigned roles with specifically assigned duties at specific stages of a flight. The PF does most of the flying, except in defined circumstances; such as planning for descent, approach and landing. The PM carries out support duties and monitors the PF’s actions and the aircraft’s flight path.

- Aerodrome weather information service (AWIS): actual weather conditions, provided via telephone or radio broadcast, from Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) automatic weather stations, or weather stations approved for that purpose by the BoM.

- A runway strip, for a runway without an instrument approach, includes a graded area around the runway and stopway, intended to: (1) to reduce the risk of damage to aircraft running off a runway; and (2) to protect aircraft flying over it during take-off or landing operations.

- The runway is a defined rectangular area on a land aerodrome prepared for the landing and take-off of aircraft.

- An aerodrome marker is an object displayed above ground level in order to indicate an obstacle or delineate a boundary.