What happened

On 15 December 2016, a Boeing 737-476SF (Special Freighter) aircraft, registered ZK-TLK (TLK), conducted a night freight flight from Sydney, New South Wales, to Melbourne, Victoria. On approach to Melbourne Airport the captain noted the aircraft nose attitude appeared to be too high and airspeed appeared to be too low for that phase of flight. After landing at Melbourne Airport, the captain was notified that a loading error occurred at Sydney Airport.

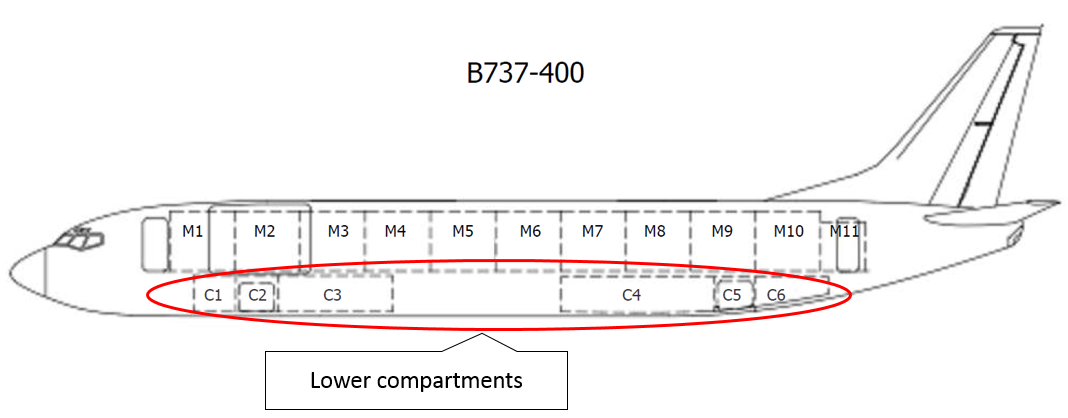

On the evening of the incident, two 737 freighter aircraft, operated by the same freight company, with the same paint scheme, were conducting freight flights into and out of Sydney Airport. The loading supervisor received loading instructions for the two aircraft shortly after they[1] started their shift at 1600 Eastern Daylight-savings Time (EDT). The loading instructions included changes to the scheduled lower compartment loads for the two 737 freighter aircraft, TLK and ZK‑JTQ (JTQ) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Boeing 737-476SF lower compartments

Source: Operator, annotated by ATSB

At about 1945, the loading supervisor completed their ramp report, which included the planned aircraft parking bays. At 2015, they travelled to the parking bays to prepare the tarmac for the aircraft arrivals and confirm the freight was prepared for loading. At 2030, they briefed their leading hand, who was responsible for directing the transfer of the road freight to the respective aircraft parking bays.

The planned loads for TLK and JTQ were distributed into containerised and non-containerised freight. Containerised freight is loaded into the upper compartments of the 737-freighter aircraft and non-containerised freight is loaded into the lower compartment. The freight was prepared on the international side of the airport and then delivered to aircraft parking bays 5 and 6 on the domestic side of the airport.

At about 2040, the loading supervisor received a phone call from their manager that there would be an aircraft swap at Sydney Airport (see aircraft swap). Therefore, the freight planned for TLK and JTQ, needed to be exchanged between the two aircraft. The supervisor was at the tarmac at the time of the phone call and did not have access to a computer, so they manually changed their ramp report and briefed the tarmac loaders about the change. However, they only swapped the aircraft registration, flight number and inbound port on their ramp report, they did not change the parking bay numbers. According to the supervisor’s ramp report, TLK was scheduled to park on bay 6 and JTQ on bay 5. However, when the two aircraft arrived at their parking bays, at about 2136 and 2138 respectively, TLK parked on bay 5 and JTQ parked on bay 6.

The staff responsible for loading the containerised freight into the upper compartments of the aircraft loaded the aircraft with reference to their copy of the load instruction report.[2] However, the non-containerised lower compartment freight was allocated to the aircraft by the loading supervisor with reference to their ramp report parking bay numbers, which were incorrect. Consequently, TLK was loaded with JTQs lower compartment freight and JTQ was loaded with TLKs lower compartment freight. The flight crew were then issued with the load instruction reports with their planned freight, which were correct for their upper compartments, but incorrect for their lower compartments. The aircraft taxied for departure at 2247 and 2253 and departed at 2300 and 2302 respectively.

Airport curfew

While the loading supervisor was supervising the distribution of freight for the aircraft, they were also mindful of the airport curfew time of 2300. The priority for the loading supervisor in this situation is to ensure that the aircraft can depart on time. Therefore, they were required to closely monitor and assess the progress of the loading in order to be prepared to make a decision to stop the loading of freight if it posed a risk of delay past curfew.

Aircraft swap

The normal schedule for the two 737 freighter aircraft were as follows:

Flight TFR 21 from Brisbane to Sydney would depart outbound from Sydney as TFR 22 for Melbourne.

Flight TFR 34 from Adelaide to Sydney, would depart outbound from Sydney as TFR 41 for Brisbane.

On the night of the incident, JTQ operated as TFR 21 from Brisbane to Sydney and TLK operated as TFR 34 from Adelaide to Sydney. The aircraft swap in Sydney required JTQ to depart from Sydney as TFR 41 for Brisbane and TLK to depart from Sydney as TFR 22 for Melbourne.

Weight and balance

The two 737 freighter aircraft had a maximum take-off weight of 68,039 kg. The centre-of-gravity limits for the aircraft, represented as an ‘index’,[3] varied with respect to the weight of the aircraft in a non-linear manner. Table 1 depicts the planned and actual data for TLK and Table 2 depicts the planned and actual data for JTQ. The actual weight and balance for TLK was within limits, but while the weight for JTQ was within limits, the centre of gravity was marginally forward of the forward centre-of-gravity limit.[4] The weight and balance calculation is used to provide the aircraft horizontal stabiliser adjustment setting for take-off. The difference between the planned and the actual required stabiliser settings was minimal for both aircraft.

Table 1: ZK-TLK weight and balance

| Planned taxi weight | 58,178 kg | Index | 35.1 |

| Actual taxi weight | 59,937 kg | Index | 35.7 |

| Planned landing weight | 54,217 kg | Index | 33.4 |

| Actual landing weight | 55,976 kg | Index | 34.0 |

| Stabiliser adjustment figures: | |||

| Planned flaps 1 & 5 | 4.4 | Planned flaps 15 | 3.6 |

| Actual flaps 1 & 5 | 4.3 | Actual flaps 15 | 3.6 |

Table 2: ZK-JTQ weight and balance

| Planned taxi weight | 58,629 kg | Index | 23.3 |

| Actual taxi weight | 56,875 kg | Index | 22.6 |

| Planned landing weight | 54,533 kg | Index | 23.1 |

| Actual landing weight | 52,779 kg | Index | 22.4 |

| Stabiliser adjustment figures: | |||

| Planned flaps 1 & 5 | 5.0 | Planned flaps 15 | 4.3 |

| Actual flaps 1 & 5 | 5.1 | Actual flaps 15 | 4.4 |

Safety analysis

Several changes to the planned loading of the aircraft were communicated to the loading supervisor on the afternoon and evening of the incident. The loading supervisor incorporated the initial change to the lower compartment freight into their ramp report and communicated the plan to the staff. When the loading supervisor was notified that an aircraft swap would occur in Sydney, they were on the tarmac and performed a manual update to their ramp report. However, their manual update did not include the change in parking bay numbers.

The loading supervisor referred to their ramp report to direct the loading of the lower compartment freight planned for TLK and JTQ. The staff loading the upper compartments referred to their load instruction reports, which had the correct parking bays. At this time, the supervisor’s attention was divided between the freight loading activities and the overall progress of the loading of both aircraft against the approaching airport curfew time. Consequently, the supervisor directed the planned lower compartment freight for TLK to JTQ, and the planned lower compartment freight for JTQ to TLK.

The pilot of TLK reported that the aircraft’s flight management computer determines the airspeed to be flown on final approach based on aircraft weight. They entered a zero-fuel weight into the flight management computer based on the planned load, which was less than the actual load. Therefore, the target airspeed flown was slower than required for the actual weight of the aircraft and the aircraft nose attitude increased in order to produce sufficient lift to maintain the approach flight path.

Findings

These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

- The loading supervisor made a manual change to their ramp report but did not include a change to the aircraft parking bay numbers; this resulted in them directing the lower compartment freight for TLK to JTQ, and the lower compartment freight for JTQ to TLK.

- JTQ was operated with a centre of gravity marginally forward of the limit.

Safety action

Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence.

Loading supervisor

As a result of this occurrence, the loading supervisor has advised the ATSB that they have taken the following safety actions:

Cross-check

During loading of the aircraft lower compartment freight, an independent cross-check will be made of the freight destination against the load instruction report.

Safety message

This incident highlights the risk associated with a single source of error propagating through a safety critical process. Following this incident, the loading supervisor reported that the lesson they learned was to have their work cross-checked whenever feasible.

Aviation Short Investigations Bulletin - Issue 59

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2017

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

_________

- Gender-free plural pronouns: may be used throughout the report to refer to an individual (i.e. they, them and their).

- The load instruction report (LIR) includes the aircraft registration, flight number, destination and description of planned load with reference to the respective aircraft upper and lower compartments. The LIR is issued by the load control centre and therefore incorporated all the changes which were communicated to the loading supervisor.

- ‘Index’ is a number calculated from aircraft weight and centre of gravity position to represent the aircraft moment. The aircraft index is referenced from a point near the centre of gravity and permits simplified centre of gravity calculations when loading the aircraft.

- A centre of gravity forward of the limits can adversely affect the stability and control of the aircraft.