What happened

On 9 December 2016, a QantasLink Bombardier DHC-8-402, registered VH-LQG (LQG), departed runway 16 left at Sydney Airport. The aircraft was operating a scheduled passenger flight from Sydney to Tamworth, New South Wales. The captain was the pilot monitoring (PM) and the first officer the pilot flying (PF).[1] At the time of departure, windshear conditions existed in the vicinity of Sydney Airport and because of this, the flight crew used normal take-off power.[2]

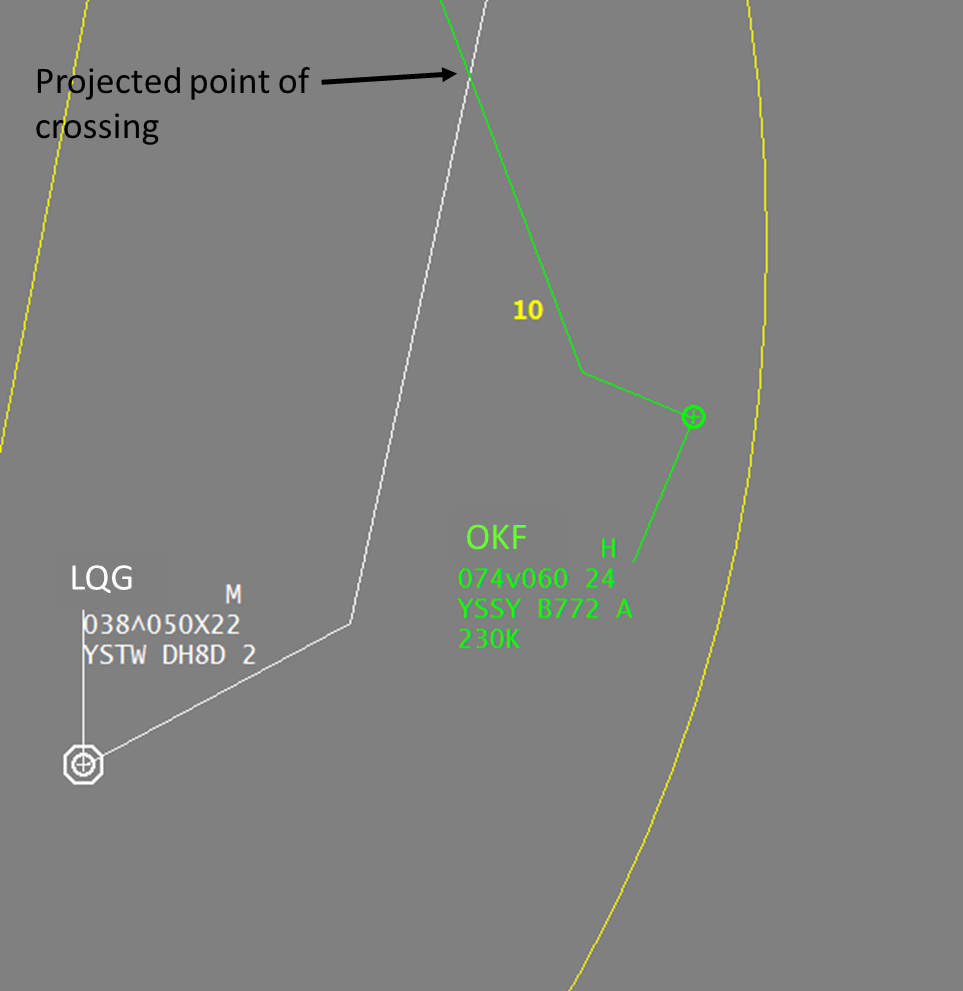

When LQG departed, an Air New Zealand Boeing 777-219ER, registered ZK-OKF (OKF), operating a scheduled passenger flight from Auckland, New Zealand, was on descent to Sydney from the east, assigned 6,000 ft by the Sydney Approach controller. The projected routes of the aircraft crossed approximately 11 km east of Sydney (Figure 1) and the Approach controller had assigned OKF an altitude of 6,000 ft to provide separation with LQG, who would be assigned 5,000 ft.

At 1407 Eastern Daylight-saving Time (EDT), LQG became airborne and after passing 500 ft, the PF turned the aircraft to an assigned heading of 090. When this turn was made, the flight crew had the go-around (GA) vertical mode selected on the aircraft flight guidance control panel with the altitude select (ALT SEL)[3] mode. After passing the acceleration altitude[4] of 1,100 ft, the PF requested the PM to select the indicated airspeed mode and a speed of 185 kts. The PM did this and then, at 1407:45, they contacted Sydney Departures while the PF engaged the autopilot.

When the PM contacted Sydney Departures, they reported passing 1,900 ft, heading 090 and climbing to an assigned altitude of 3,000 ft. Sydney Departures identified LQG on radar and instructed them to climb to an altitude of 5,000 ft. The PM read back this instruction and the flight crew correctly updated the autopilot with the new altitude and engaged the ALT SEL mode.

At 1408:12, as the aircraft climbed through 2,600 ft, Sydney Departures instructed LQG to track direct to waypoint KAMBA.[5] The position was entered into the flight management system and the autopilot was set to the lateral navigation mode. The aircraft then commenced turning left towards KAMBA.

At 1408:38, as the aircraft climbed through 3,800 ft (Figure 1), Sydney Departures advised LQG there would be a short delay at 5,000 ft due to traffic above them. This was acknowledged by the PM.

Figure 1: Disposition of aircraft when LQG was passing 3,800 ft direct KAMBA and showing the projected point of crossing.

Source: Airservices Australia, modified by the ATSB

Also, around this time, with the aircraft now tracking to KAMBA, the PF increased the airspeed setting from 185 knots to 210 knots. Almost simultaneously, the autopilot altitude mode changed to capture the assigned altitude.

The adjustment of the airspeed setting, while the autopilot was in altitude capture mode, resulted in the autopilot reverting from altitude capture mode to pitch mode, which meant the autopilot would now not stop the aircraft climb at 5,000ft.

Consequently, the PF decided to disconnect the autopilot and commenced hand flying the aircraft. They pitched[6] the aircraft nose down, to reduce the rate of climb, and simultaneously the PM selected the autopilot indicated airspeed and ALT SEL modes. Once these modes were selected, the PF attempted to reconnect the autopilot so the aircraft would maintain 5,000 ft. Before ensuring the autopilot had reconnected, they became aware of the conflicting traffic (OKF) and obtained its position by referencing the traffic alert and collision avoidance system (TCAS)[7] display. During this time, as the autopilot had not been correctly reconnected, the aircraft continued to climb.

After sighting OKF, the PF looked back at the aircraft instrumentation and observed the aircraft had climbed through 5,000 ft. This coincided with an altitude alert from the autopilot, which indicated that the selected altitude was exceeded. The PF responded by again pitching the aircraft nose down to stop the climb and return the aircraft to 5,000 ft. The maximum altitude LQG reached was 5,600 ft[8] before the aircraft began to descend.

Prior to the altitude excursion, the air traffic control system presented a short-term conflict alert (STCA), to both the Sydney Approach and Departures controllers. In response to the STCA, both controllers monitored the altitude of LQG to ensure the aircraft would maintain 5,000 ft. When the Sydney Departures controller observed LQG continue to climb, they issued the flight crew a safety alert,[9] requested confirmation that the aircraft was maintaining their assigned altitude and issued them a heading instruction to turn away from OKF. The Sydney Approach controller issued the flight crew of OKF a safety alert and instructed them to stop their rate of descent. In response, the flight crew of OKF advised they would level out and reported they were over the top of LQG and would be able to sight them again shortly. During the conflict, the lowest altitude OKF reached was 6,800 ft.

Separation Standards

The Sydney Approach and Departures controllers had anticipated that LQG and OKF would pass with less than the required 3 NM (5.6 km) surveillance separation between the aircraft. LQG subsequently passed approximately 0.5 NM (1 km) behind OKF. As surveillance separation did not exist, 1,000 ft vertical separation was required. In applying vertical separation, using pressure derived altitude information, tolerances need to be applied. When these tolerances are considered, the 1,200 ft displacement between the aircraft was not adequate to apply vertical separation. Consequently, the level excursion by LQG resulted in a loss of prescribed separation.

Operation of Autopilot

In multi-crew operations, standard operating procedures are established to support the principles of crew resource management (CRM). This includes defining the roles of the PF and PM in relation to autopilot selections. The captain of LQG reported that if the autopilot is engaged, the PF will make the autopilot selections. If the PF is hand flying the aircraft, the PM will make the selections, under the direction of the PF. In both sets of circumstances, visual and verbal cross-checks are made to help identify any potential errors.

Pilot monitoring comments:

- After they had selected the correct modes, they believed the PF had reconnected the autopilot. At this time, their attention was divided between managing other radio transmissions and monitoring the PF’s actions.

- The requirement to maintain 5,000 ft on departure was received regularly and something they monitored closely. In normal circumstances, the autopilot would remain engaged.

- The PM advised that they should have been monitoring the PF’s actions more closely.

Pilot flying comments:

- They were aware that when the autopilot mode changed to altitude capture, as they used the speed control, the autopilot mode could change to pitch. So, when this occurred, they disconnected the autopilot rather than concentrating on changing the modes with a high rate of climb close to the required altitude.

- They thought they had reconnected the autopilot after the PM had reset the modes, but were distracted by looking outside the aircraft for the conflicting traffic and did not confirm the autopilot had reconnected.

Safety analysis

When the PF initiated the speed increase to 210 knots, the autopilot had not commenced capturing the assigned altitude. The speed increase at this stage of flight was reported as consistent with company practice of increasing speed when tracking towards the intended destination.

As the PF increased speed, the autopilot started to capture the assigned altitude. These near simultaneous events resulted in the autopilot reverting to pitch mode. The potential for the autopilot to behave in this manner was known to the flight crew. It is probable that the altitude capture occurred earlier than expected, due to the aircraft’s rate of climb being unusually high. The selection of normal take-off power on departure contributed to this high rate of climb.

The PF became concerned that the autopilot was not correctly configured to maintain the assigned altitude and disconnected the autopilot to hand fly the aircraft. After the PM had selected the correct autopilot modes, the PF, believing the autopilot would successfully maintain the aircraft at 5,000 ft, decided to reconnect the autopilot. They attempted to do this but the action was not successful. The PF did not realise this and the PM did not correctly confirm the status of the autopilot.

It was probable that the PF was distracted with looking for the conflicting traffic, rather than ensuring they had successfully reconnected the autopilot.

The loss of separation subsequently occurred after LQG did not maintain 5,000ft on a track that conflicted with OKF.

Findings

These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

The PF increased the aircraft speed at approximately the same time as the autopilot commenced capturing the selected altitude. This resulted in the autopilot mode changing and influenced the PF’s decision to disconnect the autopilot.

- The PF did not engage the autopilot correctly and became distracted before ensuring it was connected, resulting in the aircraft climbing through the assigned level. The PM was also not aware that the autopilot had not been correctly reconnected.

Safety Action

Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence.

Operator

As a result of this occurrence, the aircraft operator has advised the ATSB that they have taken the following safety action:

Further training was provided to both the PM and PF in the areas of situational awareness, human factors and operational decision-making during high workload scenarios, including a review of aircraft automation technology and procedures. The crew members were also required to demonstrate competency prior to return to flying duties.

Safety message

Maintaining separation in high traffic terminal areas, such as Sydney, requires that flight crews strictly adhere to air traffic control instructions. As highlighted in this occurrence, any deviation has the potential to reduce safety margins.

During this occurrence, the interactions between the crewmembers were not effective in responding and managing the encountered threats and highlights the importance of effective CRM.

CRM is described as the practical application of all aspects of human factors including situational awareness, decision-making, threat and error management, team cooperation and communication.

One important aspect of effective CRM, is related to successful monitoring of aircraft systems and ensuring crewmembers actively cross check each other’s actions. These skills can be improved through standard operating procedures and increased emphasis and practice.

Key flight crew monitoring principles include:

- be technically proficient

- keep all team members informed

- ensure the task is understood, supervised and accomplished

- train as a team

- make sound and timely decisions.

Further information can be obtained from the Operator’s Guide to Human Factors in Aviation (OGHFA).

Aviation Short Investigations Bulletin - Issue 58

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2017

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________

- Pilot Flying (PF) and Pilot Monitoring (PM): procedurally assigned roles with specifically assigned duties at specific stages of a flight. The PF does most of the flying, except in defined circumstances; such as planning for descent, approach and landing. The PM carries out support duties and monitors the PF’s actions and the aircraft’s flight path.

- Except for the first flight of the day, usual practice is to depart at a reduced power setting.

- In the ALT SEL mode, the aircraft will climb to and then maintain the pre-selected altitude.

- The altitude the aircraft transitions from take-off speed to climb out speed.

- Waypoint: A geographical location on the route of an aircraft. KAMBA is located at S 33 29.7 E 151 26.0.

- Pitching: the motion of an aircraft about its lateral (wingtip-to-wingtip) axis.

- Traffic alert and collision avoidance system (TCAS): a type of airborne collision avoidance system (ACAS).

- Displayed pressure altitude-derived level information

- The provision of advice to an aircraft when an ATS Officer becomes aware that an aircraft is in a position which is considered to place it in unsafe proximity to terrain, obstructions, active restricted or prohibited areas, or another aircraft.