What happened

On 7 December 2016, a Boeing 737-8FE aircraft, registered VH-YFT (YFT) was parked on bay 3 (Figure 1) at Hobart Airport, Tasmania, as the crew prepared to conduct Virgin Australia flight VA1531 to Sydney, New South Wales. The flight crew consisted of a captain and first officer, and a check captain seated in the jump seat between them.

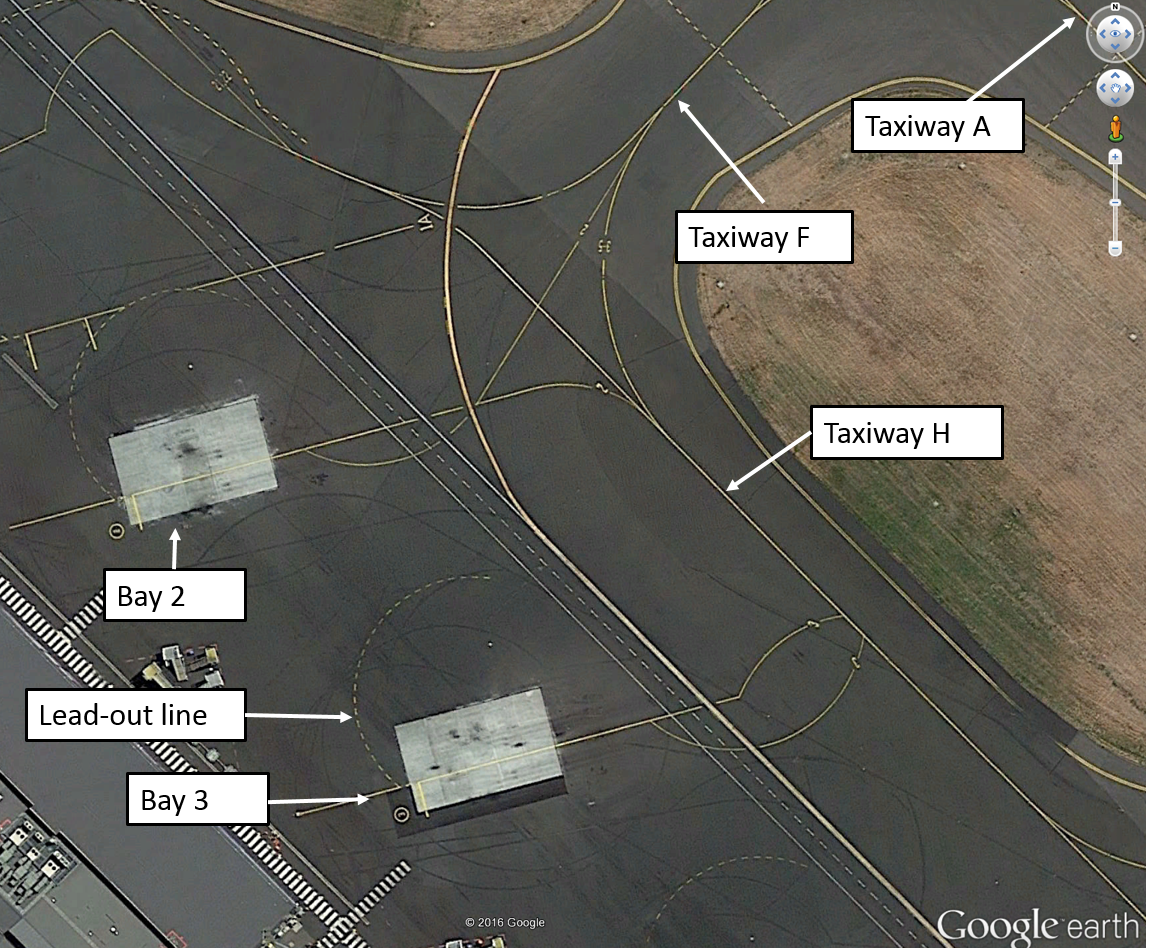

Figure 1: Hobart Airport – aerodrome diagram

Source: Airservices Australia annotated by ATSB

At about 0945 Eastern Daylight-saving Time (EDT), another Virgin Australia Boeing 737-8FE aircraft, registered VH-VUP (VUP), landed at Hobart Airport and parked on bay 2, adjacent to and north of YFT. The bays required that the aircraft departs using a power-out taxi[1], as there were no tug facilities available at Hobart Airport.

By 0950, the flight crew of YFT had received the final load sheet[2] electronically via the aircraft communications addressing and reporting system (ACARS). Due to an issue with printing a copy of the load sheet on the ACARS printer, the crew requested, and received, a paper copy of the load sheet from the dispatcher.[3] This issue caused a slight delay in pre-flight preparations. After starting the engines, the captain gave the dispatcher the instruction to disconnect their headset from the aircraft, which the dispatcher did, then exchanged thumbs up to indicate all was clear. The dispatcher then walked to the left wingtip of the parked aircraft (VUP) and stood with their arms out and thumbs up to indicate YFT was clear of obstacles, particularly the wingtip of VUP.

At 1012:12, the first officer of YFT contacted the Hobart surface movement controller (SMC) on Ground frequency and requested a clearance to taxi. The SMC then instructed the crew of an Airbus A320 aircraft that had commenced taxiing from bay 4, to vacate the apron area via taxiway H (Figure 2).

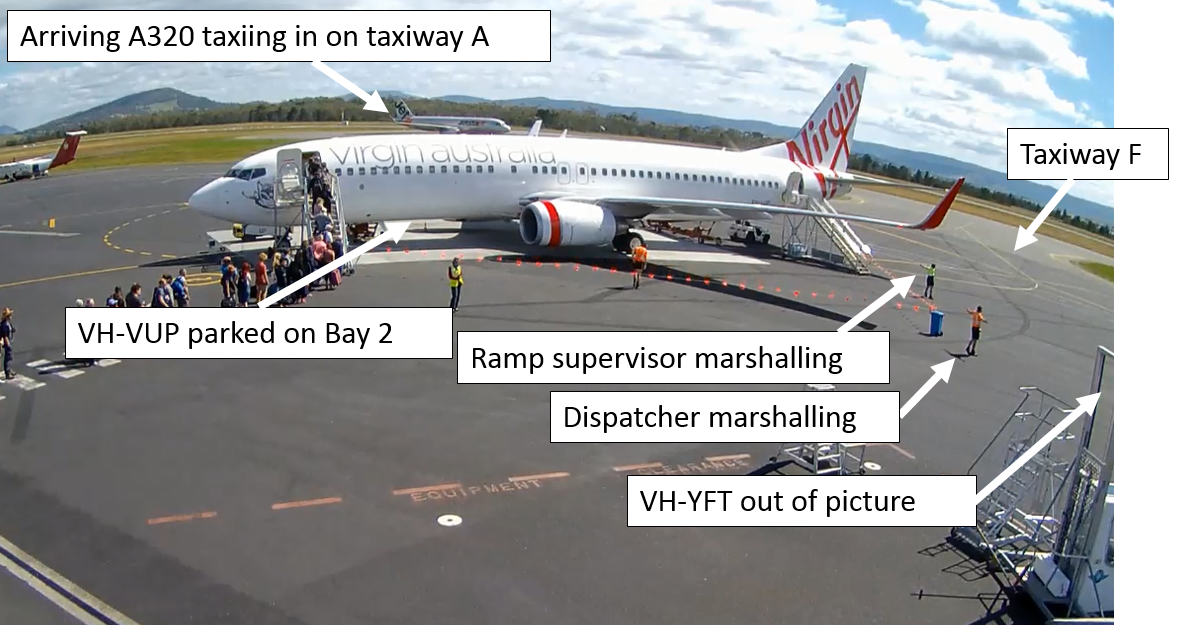

Figure 2: YFT starts taxiing from bay 3 at Hobart Airport

Source: Airport operator annotated by ATSB

The SMC then advised the crew of YFT that the A320 on their ‘left hand side’ was taxiing out via H and that they were to follow that aircraft via H (and D) to holding point D for runway 30. The first officer read back ‘follow Jetstar A320 behind, behind him via hotel holding point delta runway 30’. At about 1013, the captain commenced turning the aircraft to the right, out of the bay, with the nose wheels just inside the marked lead-out line (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Hobart apron area showing the lead-out line on bay 3

Source: Google earth annotated by ATSB

At that time, another A320 aircraft had landed and was taxiing in towards the parking bays from the north. During the initial turn out of the parking position, the captain became aware of the inbound A320 on taxiway A and became uncertain as to which A320 the controller had instructed them to follow, and whether the inbound A320 would taxi past them via taxiway F. The first officer had also seen the A320 taxiing down A towards F and pointed it out to the captain.

The captain elected to stop the aircraft and clarify their taxi clearance. YFT stopped part way through the turn, about 90° from its parked position (Figure 4). At that time, the nose wheels were inside the lead-out line, and the aircraft was pointing towards the left wingtip of VUP.

Figure 4: YFT stopped taxiing during the turn out of bay 3

Source: Airport operator annotated by ATSB

The ramp supervisor[4] was at the far side of the parked aircraft (VUP) preparing it for departure, when YFT stopped. The ramp supervisor saw that YFT had stopped during the turn out, which was unusual, therefore moved to a position near the dispatcher, who was at the left wingtip of VUP, to where they could communicate with the flight crew if required and have line of sight to check for wingtip clearance between the two aircraft (Figure 5).

Figure 5: VUP parked on bay 2 with ground crew marshalling and A320 inbound

Source: Airport operator annotated by ATSB

When YFT had stopped, the flight crew noticed that they had inadvertently omitted to write the automatic terminal information service (ATIS)[5] reference letter on their take-off data card. The first officer switched their radio to the appropriate frequency to listen to the ATIS, while the captain temporarily took over responsibility for communications with air traffic control (ATC) on Ground frequency.

At 1014:00, after seeing YFT stop during the turn, the SMC instructed the crew of YFT to ‘continue to taxi via taxiway H, you are number one to inbound traffic and the other traffic is well clear’. About 20 seconds later, after confirming the clearance with the captain (and switching the radio back from the ATIS to the Ground frequency), the first officer acknowledged the clearance with the call sign ‘Velocity 1531’.

By the time the first officer acknowledged the clearance, the captain had recommenced taxiing, while watching the A320 on taxiway A to make sure that it was going to hold its position. After stopping, the captain removed their hand from the tiller, which caused the nose wheels of YFT to centre. Therefore, the aircraft moved forwards in a near straight line for about 2 seconds and crossed the lead-out line, before the right turn resumed.

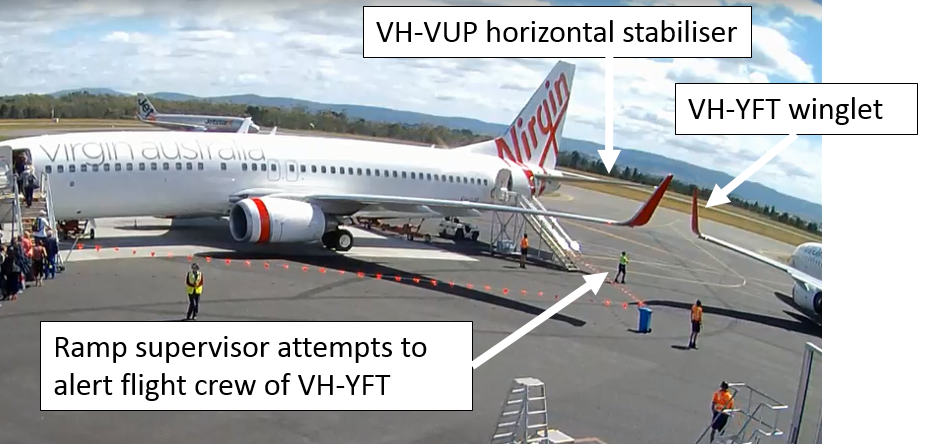

As the aircraft recommenced taxiing, the dispatcher initially observed the wingtips of the two aircraft clear each other. However, as YFT then tracked towards the tail of the parked aircraft as it started to turn, the ramp supervisor assessed that a collision between the left wingtip of YFT and left horizontal stabiliser of VUP was imminent. The ramp supervisor commented that they then lowered their arms towards a crossed position to show that clearance between the two aircraft was reducing,[6] and attempted (unsuccessfully) to make eye contact with the flight crew (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Collision imminent

Source: Airport operator annotated by ATSB

About 30 seconds after recommencing the taxi, as YFT continued to turn, the left wingtip collided with the horizontal stabiliser (tailplane) of VUP (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Contact between YFT left winglet and VUP left horizontal stabiliser

Source: Airport operator annotated by ATSB

The winglet of YFT was damaged (Figure 8) as was the horizontal stabiliser of VUP (Figure 9). No one was injured.

Figure 8: Damage to YFT left winglet

Source: Aircraft operator

Figure 9: Damage to VUP left horizontal stabiliser

Source: Aircraft operator

Safety analysis

Parking bays

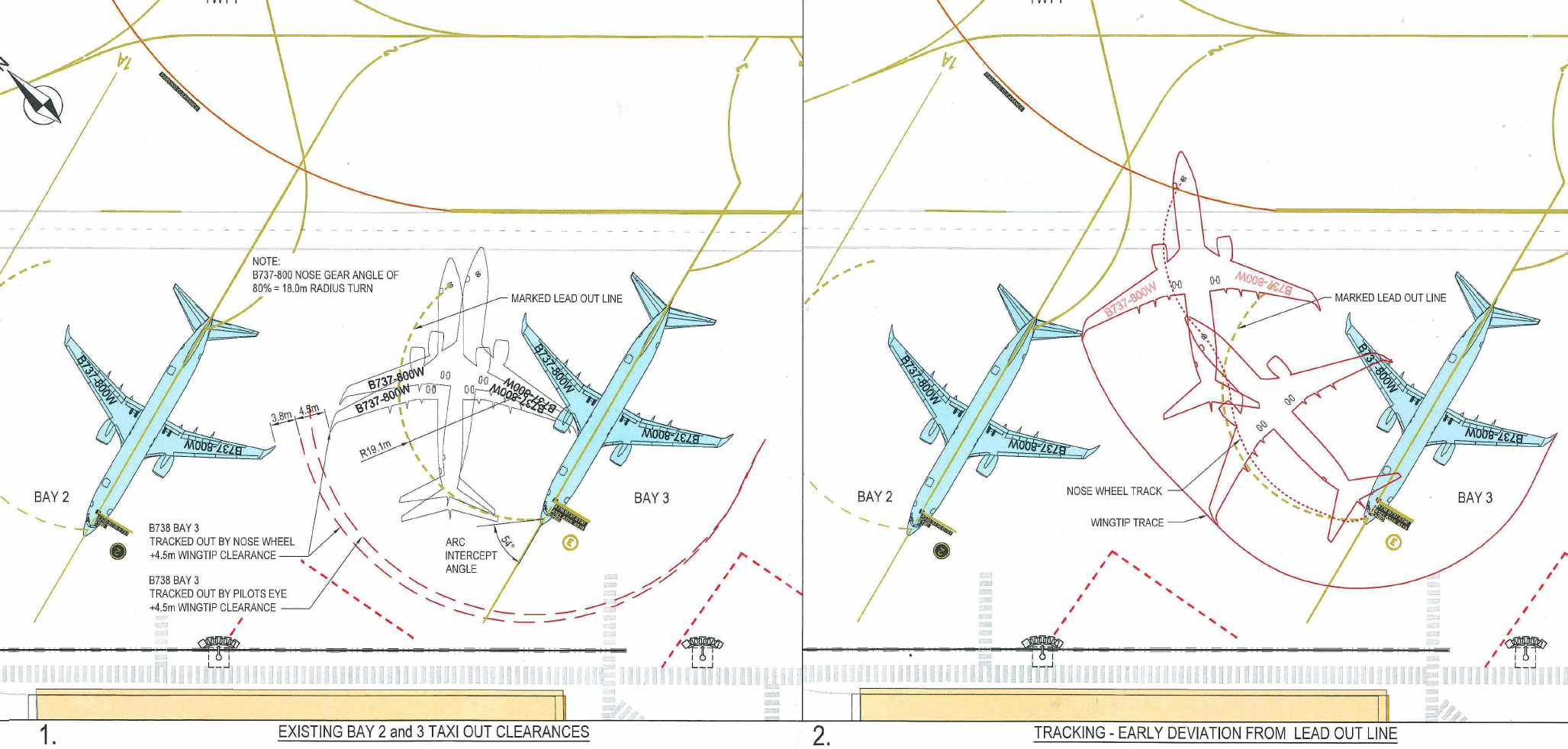

The Hobart Airport operator reported that the bays were surveyed regularly to ensure they met the required standards. The airport operator constructed a schematic diagram of the aircraft’s taxi path from the CCTV footage and the aircraft dimensions on the surveyed apron markings (Figure 10).

The flight crew commented that the design standard for the parking bays meant that they were far too close to be comfortably safe to conduct a power-out taxi when there is an aircraft in the adjacent bay. Furthermore, a bit more spacing between the bays may prevent a similar incident occurring. The captain also commented that consideration of operational acceptability criteria, in addition to technical design specifications, prior to the commissioning of any parking bay and its associated taxi guidance line would facilitate required changes to the bay and mitigate additional threats peculiar to the local environment.

The captain commented that the (power-out) bays in Hobart are not aligned at right angles to taxiway H. This tends to give a false sense of being clear of adjacent aircraft once the cockpit is well past the aircraft and heading towards taxiway H, as the wingtips are so far behind the flight deck and outside the normal viewing arc of the pilots.

Figure 10: Airport survey markings showing B737 aircraft taxi track with nose wheel on lead-out line (left) and approximate incident taxi path (right)

Source: Airport operator

Position of VUP

VUP was parked with the nose wheels approximately 450 mm aft of the stop mark on bay 2, and the main landing gear was offset longitudinally (relative to the aircraft’s heading on the bay) about 380 mm left of the bay centreline. These were well within allowed tolerances and the aircraft was assessed by ground crew to be parked in the correct position. The crew of VUP had been guided to the parking position by ground marshals.

However, the position of VUP’s tail slightly left of centreline and aft (measured after the accident), reduced the available clearance between the two aircraft.

Turning geometry

When the aircraft stopped, the nose wheels straightened, and the aircraft subsequently taxied outside the marked turning circle.

When the captain releases the tiller on a Boeing 737 aircraft[7] during taxi, it will tend to centre the nose-wheel steering and straighten the nose wheels. When the aircraft then starts to move, the captain cannot immediately turn the nose-wheel steering before the aircraft moves without considerable use of thrust and excessive load on the nose landing gear. As the aircraft starts to move forwards, the captain turns the tiller in the desired direction and the nose wheels will start to turn the aircraft.

When YFT stopped, the nose wheels were inside the lead-out line. If the nose wheels track on (or inside) the lead-out line, the wingtip will clear a correctly parked aircraft on the adjacent bay, but it is necessary to keep a continuous turn going. The check captain commented that if you stop the aircraft, particularly if it is heavy, a significant amount of thrust is required to then keep the aircraft on the line. The captain commented that they used caution with the thrust setting because of passengers boarding the aircraft on the adjacent bay. The check captain also stated that there was not a lot of manoeuvring room with ‘power-out’ bays. There is a risk that the aircraft has to go straight ahead for 2-3 m to get the turn going again and there is no allowance made for that in the geometry of the bay.

The captain commented that there is an inherent error in determining where the nose wheel is tracking in relation to a taxi guidance line, in the Boeing 737, during turns. The nose wheel is behind and laterally offset from the captain’s seating position. As such, its position in relation to the line can only be estimated. On power-out bays, flight crew cannot see the position of the aircraft on the lead-out line at any time.

After stopping, the captain could no longer see the lead-out line, which was then beneath and behind the cockpit. The aircraft taxied forward across the lead-out for about 1–2 seconds then turned to the right towards the H taxiway line. There was no marked line connecting the lead-out line with taxiway H.

Ground crew interpretation of taxi track

When the aircraft stopped, the dispatcher noticed that the nose wheels were inside the line, which was normally an indication that the aircraft would stay well clear of an aircraft parked on bay 2. The aircraft then proceeded for about 2 seconds at an angle that was not normal, and both the ramp supervisor and the dispatcher thought the aircraft may have been heading towards taxiway A via the exit (F) behind bay 2 rather than continuing to turn to the right and along the normal path onto taxiway H.

The dispatcher reported that they were not initially concerned about the aircraft’s track, because a bit of momentum was needed to turn the aircraft and get moving. When the wingtip of YFT taxied clear of the wingtip of VUP where the dispatcher was standing, they assumed the aircraft would continue turning and exit the bay, but instead it kept going towards the parked aircraft, which they commented was very unusual.

Communication between ground crew and flight crew

In accordance with normal procedures, the dispatcher unplugged their radio connection to the flight crew before the aircraft commenced taxiing.

The dispatcher commented that they were unsure as to why the aircraft had stopped during the turn, but assumed it was because the flight crew were communicating with ATC. The ground crew radios are not on the ATC frequency and therefore they cannot hear transmissions between ATC and flight crew.

When the aircraft stopped, the ramp supervisor moved to where they could see if the flight crew flashed the nose-wheel lights to indicate a reconnect (of ground-air crew radio communications) was required, but they did not. There were also no hand signals from the flight crew to indicate they needed to reconnect. The ramp supervisor is the only person in the ground crew with a ground-to-air licenced, hand-held radio, so they wanted to get into position to communicate with the flight crew if they requested a reconnect.

As the aircraft continued its turn off the bay, YFT’s wingtip clearance was decreasing due to its proximity to the tailplane of VUP, although it had safely cleared the wingtip of VUP. The dispatcher was then no longer in sight of the flight crew. The ramp supervisor was unable to make eye contact with the captain (seated in the left seat) and commented that the captain appeared to be looking directly forwards.

The ramp supervisor commented that they lowered their arms towards a crossed position to indicate reducing clearance, but that action was not apparent on the CCTV footage of the accident. The check captain commented that lowering of the arms to the crossed position as stated by the ramp supervisor was not shown in the operator’s manual as a procedure to show reduced wing tip clearance.

According to the manual, the correct signal for requiring the aircraft to stop was ‘arms repeatedly crossed above head (the rapidity of the arm movement should be related to the urgency of the stop (i.e. the faster the movement, the quicker the stop)’.

The captain commented that they had seen the thumbs up from the wing walker at the wingtip of the parked aircraft (the dispatcher) and the wing walker near the tailplane of the parked aircraft (the ramp supervisor). They were the only signals the captain sighted and assumed therefore that they were clear of the parked aircraft. If there was any doubt about their clearance from the parked aircraft, they would contact ground staff via radio on their company operations frequency and request assistance, but they did not have any doubt. They had received the all clear signal from the ground crew and thought that they were clear of the parked aircraft and safe to continue.

The captain commented that it would be better to have verbal communication with the marshallers all the way out of the parking bay to have immediate communication if the clearance is insufficient. A verbal warning would be an immediate trigger to stop.

Training

The check captain commented that they consider the turning bays at Hobart to be tight. When training new captains, they always encourage them to ensure that they apply sufficient tiller during the turn out, and that sufficient thrust is applied to keep the aircraft turning. In addition, they suggest using the technique of using slightly more thrust on the outside engine to assist in keeping the aircraft turning.

The check captain also stated that there was no standard procedure in the company for training captains to taxi the aircraft. Training captains instil the importance of using a minimum radius turn out of the bay, appropriate power application and tiller technique, and instruct how to go about requesting assistance with marshaller guidance. Captains are instructed on the visual (hand) signals and where there is any doubt about clearance, to rely on the marshaller and keep a good lookout. If unsure of the clearance from any obstacle, they should stop, but in a turn, it is also important to keep the turn going – if you do stop you potentially have a problem.

When taxiing out of a power-out bay, they try to turn inside the lead-out line to ensure adequate clearance.

Role of ground crew

The operator commented that at the time of the incident, although provision of ‘wing-walkers’ was included in the ground handling contract between the aircraft operator and ground handling provider at Hobart Airport, the ground personnel were not specifically trained in wing walking. The dispatcher and ramp supervisor had proactively positioned themselves at the wingtip and horizontal stabiliser of VUP to assist the flight crew in maintaining clearance between the two aircraft. Wing walking or marshalling was normal procedure for the ground crew at Hobart Airport and both ground crewmembers had substantial experience in doing so.

Once the wingtip of YFT had passed the wingtip of VUP, the dispatcher’s responsibility was over because the next marshaller (ramp supervisor) was in line and the dispatcher was then out of line of sight of the flight deck. There was not usually a marshaller positioned beyond the wingtip.

The dispatcher commented that normally once the aircraft was clear from that position on the wingtip, the dispatcher would give a salute or wave to the captain and they would acknowledge with a wave, but that did not happen on this occasion. The dispatcher commented that the captain appeared to be looking straight ahead towards the exit, or they may have been focused on the marshaller ahead (the ramp supervisor).

Attention and time pressure

The captain initially got the thumbs up from the dispatcher and the ramp supervisor. Immediately before the collision, the captain’s attention was on the inbound A320, and they did not see any indication from the ground crew of reducing clearance with VUP (nor was there any evidence of such on the CCTV footage).

The captain commented that during the turn out, their attention was divided between the wing walker, watching where the aircraft was going, listening to ATC, communicating with the first officer, maintaining situational awareness and being aware of other traffic in the area.

The captain also commented that they[8] had to rise at 0345 to commute to Sydney Airport for the flight and had not slept particularly well as the flight was a line check. There was some pressure to perform well having a check captain in the jump seat. However, the captain felt fit to operate the flight and did not feel tired.

While waiting for the final load sheet to come out on the aircraft communications addressing and reporting system (ACARS), they had a problem with the ACARS printer and had to unjam it as the scheduled departure time was approaching. They requested a hard copy of the load sheet from the dispatcher but were also able to get the printer fixed and printed the load sheet from the ACARS. This caused them a slight delay and they were ready to go about 2 minutes late (scheduled departure was 1010 and they released brakes at 1013). This created some time pressure.

Clearance and traffic disposition

The presence of two A320s led the captain to doubt their taxi clearance after they started taxiing. The operator commented that the first officer’s read back of the taxi clearance, where they stated the A320 ‘behind’ rather than to their left, may also have affected the captain’s perception of which of the two A320s they were to follow. Once the aircraft started to turn, the captain could not see the A320 taxiing out (via H) but was concerned about the one inbound. The captain wanted to confirm that the inbound aircraft was going to stop.

Normally the captain would clarify the clearance with the first officer, but the first officer was listening to the ATIS at the time.

Findings

These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

- When the captain became aware of the incoming A320, they became uncertain of their clearance and stopped the aircraft to clarify.

- The aircraft taxied outside the marked lead-out line after stopping and without the application of sufficiently increased thrust or tiller input this resulted in insufficient clearance from the parked aircraft. The captain was unable to see the aircraft’s position relative to the lead-out line after stopping and the line did not continue to intersect the taxiway ahead of the aircraft.

- The bays were marked according to the standards, but the standards probably did not allow sufficient margin for non-normal situations, such as stopping during the turn.

- There was no documented procedure for either flight or ground crew to follow in the case of an aircraft stopping during the turn or crossing the lead-out line.

- The operator did not have a standard training syllabus or assessment criteria for teaching captains to taxi the aircraft.

- There was no direct means of verbal communication between ground marshallers and the flight deck once the aircraft started taxiing, although the crew could contact the movement coordinator if required.

- Wing walkers should remain in sight of the flight crew, but the captain did not see the ramp supervisor signal to indicate reducing clearance between the two aircraft. The captain’s attention was to the incoming A320.

Safety action

Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following safety action in response to this occurrence.

Aircraft operator

As a result of this occurrence, the aircraft operator has advised the ATSB that they are taking the following safety actions:

Flight crew operational notice

The aircraft operator issued a flight crew operational notice (FCON)[9] which stated that:

- When taxiing out of power-out bay, crew shall ensure the aircraft maintains the apron lead-out line until:

- the end of the lead-out line; or

- the lead-out line joins a taxiway centreline.

- This may involve an exit turn of more than 180 degrees to assure clearance from adjoining bays.

- Should the aircraft be stopped before completion of the entire turn to exit the apron, caution should be made when re-initiating movement to ensure the above requirements are maintained.

- If at any time aircraft clearance cannot be assured, the aircraft should cease taxiing and request assistance.

Training and checking notice

The aircraft operator also issued a training and checking notice (TCN) that stated ‘All Check Captains and Training Captains are requested to ensure that wingtip geometry, turn markings, turn procedures and hazards are well understood by flight crew during line training and recurrent line checks’.

Flight crew information bulletin

The aircraft operator published a flight crew information bulletin (FCIB) for educational and standardisation purposes titled Wingtip Clearance Hazard and applicable to Boeing 737 aircraft. The FCIB included information about taxiing in accordance with lead-out lines, appropriate use of ground crew, images of Hobart and other airports used by the operator, and wing and tail turning geometry for the aircraft.

The FCIB stated:

In summary, it is recommended that taxi guidance lines be adhered to, whenever practical. Continued vigilance should be employed by crews in the monitoring of obstacles during ground manoeuvring.

If there is any doubt whatsoever regarding wingtip clearance, STOP and seek guidance.

Safety message

This incident highlights the importance of aircraft operators conducting a thorough risk assessment where ground movement is confined, particularly movements involving congested power-out bays. Effective risk assessments ensure that hazards are clearly identified and well understood, and that the associated risks are appropriately managed.

To manage clearance in congested areas, communication tools between ground and flight crew should be used where possible when ground crew are providing marshalling or wing walking assistance. Hand signals rely on constant visual contact, which cannot be guaranteed. Appropriate training of ground crew regarding the use of standard hand signals is required to ensure mutual understanding and communication between flight and ground crew.

Where possible, airport authorities should consider additional margins to accommodate unusual or irregular circumstances during taxiing.

Part of Aviation Short Investigations Bulletin - Issue 60

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2017

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________

- ‘Power-out taxi’ are where the aircraft is taxied out rather than pushed back using a tug.

- Aircraft weight and balance data for the flight.

- Ground crew responsible for assisting in loading (and unloading) and preparing aircraft for departure.

- Supervisor of ground crew loading and unloading aircraft.

- The ATIS (Automatic Terminal Information Service) is an automated broadcast of prevailing airport weather conditions that may include relevant operational information for arriving and departing aircraft.

- However, this was not evident in the CCTV footage.

- The aircraft has only one tiller – and therefore can only be taxied from the captain’s seat.

- Gender-free plural pronouns: may be used throughout the report to refer to an individual (i.e. they, them and their).

- FCONs are company NOTAMs which are issued to flight crew by the flight operations department to convey new operational and technical information which is of an urgent nature. Flight crew are required to obtain and review a copy of the current FCONs at the commencement of duty each day.