What happened

On 11 September 2016, the pilot of a Cessna 172RG, registered VH-MKG (MKG), was observed moving the aircraft out of a hangar at Parafield Airport. The aircraft was positioned on the apron in front of this hangar. The pilot then hand swung the propeller to start the engine, with no one at the aircraft controls. Following the hand start, the uncontrolled aircraft taxied a short distance before colliding with a parked Piper PA-32 Saratoga. Although not struck directly by the propeller, the pilot was fatally injured either by being struck by the aircraft or in the subsequent fall as the aircraft taxied away. The pilot's dog was unsecured in the aircraft.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that the battery installed in MKG had insufficient charge to start the engine, and that the pilot started the engine by hand swinging the propeller. The aircraft was not adequately secured during the hand start, resulting in fatal injuries to the pilot and damage to another aircraft when it taxied without pilot control.

Safety message

Hand swinging an aircraft propeller is recognised across the aviation industry as a hazardous procedure. Although hand swinging is permitted under the civil aviation regulations, it should only be undertaken when no other alternatives exist to start the aircraft engine and all necessary precautions have been taken to mitigate the hazards.

Additionally, unrestrained animals in the aircraft cabin have the potential to adversely affect safety during aircraft operations.

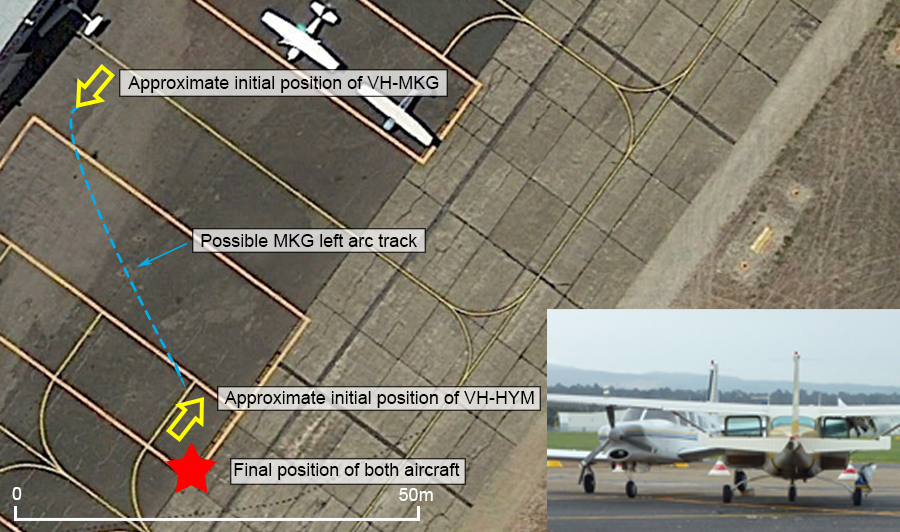

Final position of VH-MKG against the Saratoga

Source: ATSB

At approximately 1300 Central Standard Time[1] on Sunday 11 September 2016, the owner/pilot (pilot) of a Cessna 172RG aircraft, registered VH-MKG (MKG), arrived at Parafield Airport. MKG was located in a hangar on the aerodrome, where the pilot was employed on a contract basis as a check and ferry pilot and aircraft maintenance engineer.

The ATSB was advised that the pilot had been conducting part of a 100 hour inspection, and other scheduled maintenance, on MKG throughout the weekend. The battery installed in MKG had reportedly been on charge during this maintenance.

At around 1600, witnesses reported seeing the pilot manually reposition MKG outside of the hangar. The aircraft was parked, facing approximately south-west, into the wind. The witnesses observed an initial pull through of the propeller by the pilot, before the pilot returned to the cockpit area for a short time.

The pilot then returned to the front of the aircraft and hand swung the propeller for a second time, resulting in the aircraft engine starting. MKG then taxied without pilot control, turning approximately 45 degrees on a left arc, before colliding with a Piper PA-32 Saratoga, registered VH-HYM, that was parked on the apron, approximately 35m from MKG.

Throughout the engine start and uncontrolled taxi, the pilot avoided being struck directly by the propeller. However, possibly in an attempt to re-enter the cockpit to regain control of the aircraft, the pilot's fatal injuries likely resulted either from being struck by MKG as it taxied or in the subsequent fall.[2]

The impact of the collision pushed the Saratoga about 10m from its parked location. Both aircraft came to rest approximately parallel to each other, facing in opposite directions, with MKG's propeller embedded in the underside of the Saratoga's left wing. The nose cowl of MKG was also wedged under the Saratoga's wing, lifting its left main wheel clear of the ground.

The pilot's dog was found unrestrained in the aircraft cabin and was removed by emergency responders approximately 90 minutes after the accident.

Figure 1: The approximate initial and final positions of VH-MKG and VH-HYM, and the approximate track of MKG. Inset shows the final position viewed from behind MKG

Source: Google Earth, annotated by ATSB.

Starting procedures

The starting procedures for normal operations were contained in the pilot operating handbook (POH) for the Cessna 172RG. It included a checklist of actions to be taken before starting the engine and a starting engine checklist.

In normal operations, the aircraft electrical system was used to start the engine. This required the battery to have sufficient charge to engage the starter motor. Although the battery had been on charge the preceding day while maintenance was undertaken, it was not capable of maintaining sufficient charge to start the engine.

The aircraft was equipped with a ground service port where a ground power unit (GPU) could be connected. The service manual indicated a GPU was intended as a power source for prolonged ground maintenance requiring the use of electrical power. It also indicated, without restricting it to these conditions, that it could be used for cold weather starting. A GPU was available in the hangar where the aircraft was located.

Hand starting procedures

There were no specific procedures to hand start MKG. Civil Aviation Regulation 231 - Manipulation of propeller (CAR 231) permitted the pilot in command to hand swing a propeller to start the engine, provided no assistance was readily available, no passengers were on board the aircraft and adequate provision was made to prevent the aircraft moving forward.

Generic guidance on hand swinging a propeller, published by the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA), the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and various pilot forums, covered topics including:

- deciding to hand start

- positioning the aircraft

- securing the aircraft

- setting the engine controls

- having assistance.

While CAR 231 permitted hand swinging, the guidance available highlighted the increased risk associated with this starting method, and that it should be considered an emergency procedure, used only when absolutely necessary.[3]

The aircraft was positioned appropriately according to the guidance, outside of the hangar, on firm, flat, level ground, with no obstacles directly ahead.

The guidance advised that:

- chocks of an appropriate size and material should be applied to both main wheels

- the aircraft should be tied down adequately, using an appropriate restraint

- the brakes should be set

- the fuel system and engine controls set for a normal start.

CAR 231 requires the person manipulating the propeller to know the correct starting procedure for the aircraft. Additionally, it allows for assistance to be provided by having a qualified person at the controls of the aircraft, if a suitably qualified person is available. The FAA handbook noted that 'the procedure should never be attempted alone.'[4]

Securing the aircraft

Wheel Chocks

A single set of small wooden chocks were located about 15m from the hangar doors, in the approximate area MKG was positioned prior to start-up. The distance between the chocks was consistent with both the nose and main wheels of MKG, with a small gap. It was probable that this gap resulted from forward chock sliding along the ground a short distance as the aircraft rolled over it. A set of aircraft chocks consisting of two aluminium angles connected by a chain were located in the aircraft.

Brake system

The aircraft had a single disc, hydraulically actuated brake on each main landing gear wheel. The brakes were operated by applying pressure to the top of the rudder pedals. When the aircraft was parked, both main wheel brakes were able to be set by using the parking brake. The POH instructed that 'to apply the parking brake, set the brakes with the rudder pedals, pull the handle aft, and rotate it 90˚ down.' A ratchet spring then holds the park brake in position.

On-site examination of the aircraft brake system established that the park brake was inoperative. The ratchet spring from the park brake handle had fractured, which rendered the park brake system unable to independently remain locked and set. A thorough search of the aircraft cabin did not locate the remainder of the ratchet spring. Examination of the park brake assembly at the ATSB's technical facilities in Canberra was unable to indicate whether the park brake mechanism was operative prior to the accident.

Tie down

A tie down kit was located in the aircraft, but there was no provision for a tie down in the location the aircraft was parked.

Throttle control

The throttle control was of the push-pull type, incorporating a friction lock, which is rotated for the desired friction level. The throttle is open in the fully forward position and closed in the fully aft.

Post-accident inspection of the aircraft controls found the throttle to be at about one third of its possible travel. The friction knob was consistent with no friction on the throttle control.

The measured throttle position was equivalent to a higher setting than the POH engine start checklist position. However, as the friction lock was not set, it could not be determined if this was the same position as when the aircraft propeller was hand swung.

Related occurrences

A review of the ATSB occurrence database identified 39 other reported incidents involving hand starting an aircraft resulting in injuries and substantial damage to property. The database contained all reported occurrences from 1969. The majority of incidents identified inadequate aircraft restraint and excessive throttle settings as factors in the aircraft moving after a hand start. Of these, a number were identified where the aircraft park brake and wheel chocks were used but were not adequate to restrain the aircraft. This included the investigation detailed below.

ATSB investigation 199401851

The pilot attempted to start the engine for the return flight to Darwin, but the starter motor failed to operate. He then applied the handbrake, chocked the nose-wheel and hand-swung the propeller. After several attempts the engine fired then ran at a high RPM speed causing the aircraft to jump over the chock and head towards the airport fence. After unsuccessfully attempting to enter the cabin the pilot tried to grab a main wheel, but missed. He next grabbed at the tailplane but was knocked to the ground. The empty aircraft then ran through the airport fence, across a road and into a ditch, where it came to rest suffering substantial damage.

__________

- Central Standard Time (CST): Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) + 9.5 hours

- At the time of publication, the Coroner's report had not been finalised. This report will be updated if there are any significant changes to the preliminary findings

- CASA Safety Video - Prop Swinging available at https://www.youtube.com/CASABriefing

- FAA Airplane Flying Handbook, FAA-H-8083-3A, 2004

Starting procedures

Normal operating procedures for the aircraft relied on the battery having sufficient power to start the engine. Evidence gathered during the investigation indicated that the battery was known by the pilot to be unserviceable prior to the accident. It could not be determined why the battery had not been replaced prior to conducting the ground run. Similarly, it was unable to be determined why the available GPU was not used.

The pilot was known to have hand swung aircraft previously, including MKG. The use of either the park brake or wheels chocks, or a combination of both, may have been sufficient to hold the aircraft on previous occasions. However, the aircraft manufacturer indicated that neither the use of chocks nor the park brake were designed to hold the aircraft during an engine start, and were only intended to hold a parked aircraft.

The pilot was hand starting the aircraft unassisted, using only small chocks and without tying down the aircraft, and would therefore have been relying on the park brake being set. If the spring was broken prior to the park brake being set, or broke at the time the brake was set, the pilot would have been alerted to this as the park brake handle would have returned to its initial position. It remains possible that the spring failed between the time the brake was set and the time the engine was started, leaving the pilot unaware that the park brake was not set. This reinforces the recommendations to have a qualified second person at the controls when attempting to hand start.

Other factors that increased risk

Unrestrained animal

Civil Aviation Regulation 256A - Carriage of animals, allows animals to be transported on aircraft. The regulation requires any animal to be in a container or adequately restrained in order to prevent adversely affecting the safe operation of the aircraft.

While it could not be determined in this instance if the presence of the dog had any impact on the accident, an unrestrained animal in the cockpit or cabin area of an aircraft increased the risk of inadvertent interference with aircraft control settings.

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the ground handling accident involving Cessna 172RG, registered VH-MKG, Parafield Airport, South Australia on 11 September 2016.

These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

Contributing factors

- The aircraft battery had insufficient charge to start the engine, resulting in the pilot starting the engine by hand swinging the propeller.

- The aircraft was not adequately secured during the hand start and had no one at the controls, resulting in fatal injuries to the pilot and damage to another aircraft when it taxied away.

Other factors that increased risk

- Unrestrained animals in the aircraft cabin can adversely affect safety during aircraft operations.

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- Witnesses

- Maintenance staff

- the Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Adelaide Airport Limited

- Cessna (Textron Aviation)

- South Australia Police

References

FAA-H-8083-3A, Airplane flying handbook. (2004). U.S. Dept. of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration, Flight Standards Service.

Information Manual, Cessna Model 172RG. (1983). Cessna Aircraft Company, Wichita, Kansas USA

Submissions

Under Part 4, Division 2 (Investigation Reports), Section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 (the Act), the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. Section 26 (1) (a) of the Act allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to Cessna (Textron Aviation), the Civil Aviation Safety Authority and the United States National Transportation Safety Board.

Submissions were received from the Civil Aviation Safety Authority and the United States National Transportation Safety Board. The submissions were reviewed and where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2017

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |