What happened

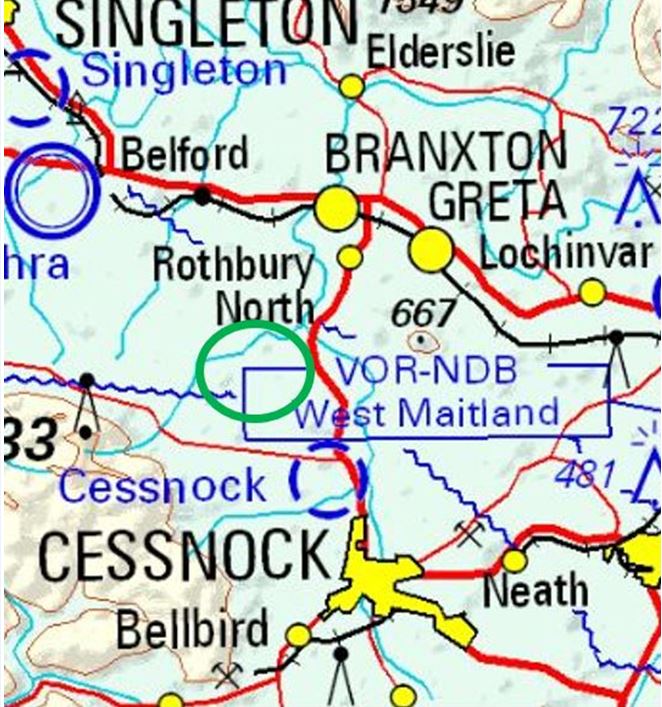

At about 0725 Eastern Standard Time (EST) on the morning of 24 April 2016, the pilot of a Kavanagh Balloons B-400, registered VH-WNV (WNV), prepared to land at Rothbury near Cessnock, New South Wales (Figure 1). On board the scenic flight were the pilot and 16 passengers. The balloon was one of a number of balloons conducting a similar scenic flight that morning.

The pilot had selected a landing site, and informed the ground crew by radio, but the light wind carried WNV, and the other balloons in the group, a little further past this site. The pilot in WNV (and the other balloon pilots) then selected a nearby paddock for landing, and updated the ground crew accordingly. The pilot lined the balloon up to land, but then noticed a small dam along the intended landing path. The pilot manoeuvred the balloon over the dam before turning off the burners, and making a gentle landing.

Figure 1: VH-WNV landing area (green circle)

Source: Airservices Australia: Extract of Sydney World Aeronautical Chart, annotated by ATSB

The manoeuvring over the dam resulted in the balloon being a little closer to the tree line than ideal (Figure 2). Mindful that the ground crew had to pack up the 400,000 cubic foot balloon once the passengers has disembarked, the pilot advised them that they would move the balloon back about 10m further from the trees. To assist with this process, and make the balloon more buoyant, the pilot checked the neck of balloon was still sufficiently open, and then turned on the pilot light of one of the two burners.

Moments later, the pilot again checked the neck of the balloon and noticed the gentle wind had blown part of the deflating balloon back on itself and there was black smoke emanating from this area. The pilot then observed that some of the fabric had melted and had begun to drip onto the occupants of the basket. The pilot quickly re-directed the ground crew from the task of pulling the top of the balloon down, to assisting the passengers disembark and move away to a safe area.

To avoid any potential of the balloon becoming aloft during the disembarkation process, the pilot pulled the smart vent[1] to rapidly release air. The pilot reported it was difficult to assess the extent of the fire from the basket, but they were aware that the balloon envelope ‘sliding’ on itself was adding more fabric as ‘fuel’ to the fire.

The balloon envelope deflated and landed next to the basket. The pilot (still on board) and the ground crew, after ensuring the passengers were safe, discharged fire extinguishers. Within a few minutes, the crew were able to spread the balloon envelope out and extinguish the fire.

During the emergency disembarkation, two of the passengers received minor burn injuries. The lower section of balloon envelope was substantially damaged.

Figure 2: Kavanagh Balloons B-400, VH-WNV at Rothbury

Source: Pilot

Pilot comments

The pilot had logged over 1,330 flying hours, with about 350 hours on the Kavanagh Balloons B‑400.

In hindsight, the pilot advised that the decision to move the balloon back 10 m to assist the ground crew with the collapse and pack-up of such a large balloon was not the correct one. Other balloons landing nearby did not attempt to move their balloons away from the tree line.

Safety message

This occurrence highlights how quickly events may change. The simple decision by an experienced pilot to move the balloon back 10 m from the tree line to assist the ground crew inadvertently led to a fire.

The Federal Aviation Administrations’ (FAA) comprehensive Balloon Flying Handbook (2008) covers all aspects of balloon flying including aeronautical decision-making. Aeronautical decision-making is a systematic approach to the mental process used by pilots to determine the best course of action in response to a given set of circumstances. It builds on the foundation of conventional decision-making but enhances the process to decrease the probability of pilot error.

As almost all ballooning operations are conducted as single-pilot operations, ballooning uses a variant of crew resource management, known as single-pilot resource management. This integrates:

- human resources

- situational awareness

- decision-making process

- risk management

- training.

One way in which the risk management decision path can be framed is through the perceive-process-perform model, which offers a structured way to manage risk.

- Perceive the hazard by looking at:

– pilot experience, currency, condition

– aircraft performance, fuel

– environment (weather, terrain)

– external factors.

- Process the risk level by considering:

– consequences posed by each hazard

– alternatives that eliminate hazards

– reality (avoid wishful thinking)

– external factors (‘get-home-itus’).

- Perform risk management:

– transfer – can someone be consulted?

– eliminate – can hazards be removed

– accept – do benefits outweigh risk?

– mitigate – can the risk be reduced?

Other decision-making models are also covered in the manual.

Aviation Short Investigations Bulletin- Issue 52

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2016

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________