What happened

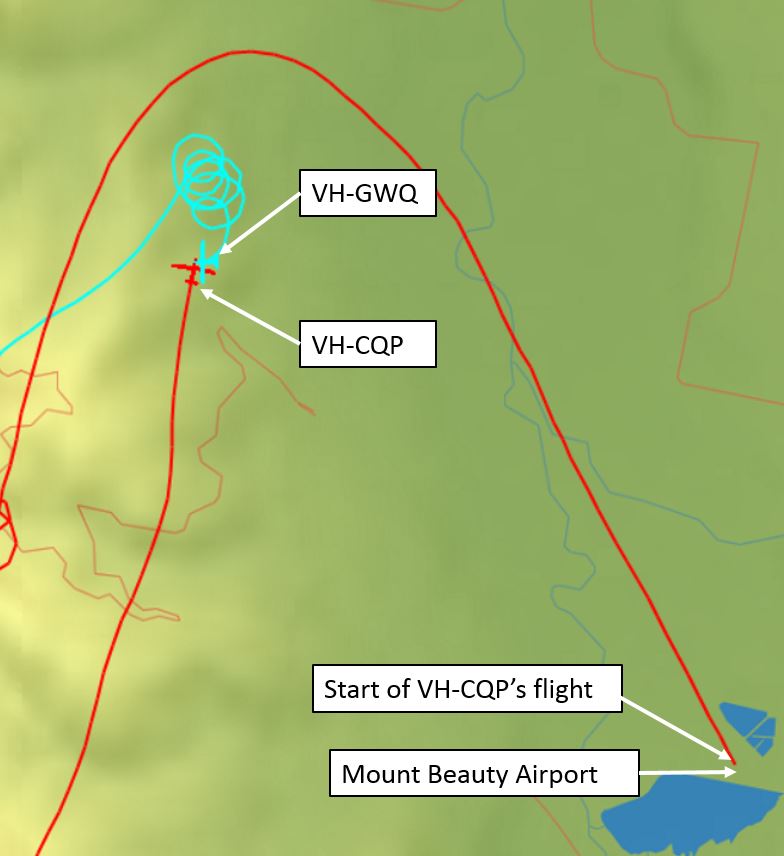

On 28 March 2016, at about 1306 Eastern Daylight-saving Time (EDT), a Schemp-Hirth Janus glider, registered VH-GWQ (GWQ) launched from Porepunkah Airfield, Victoria, for a pleasure flight. On board were two pilots. The pilot seated in the rear seat was the pilot in command for the flight. The glider tracked over Simmons Gap, to a ridge about 3 km north-west of Mount Beauty Airport (Figure 1). The pilots could hear and see other gliders being towed onto the ridge. They joined a thermal[1] and climbed in tight orbits (‘thermalling’) in a clockwise direction.

Figure 1: Relative tracks of gliders VH-GWQ and VH-CQP and positions at 1355:02

Source: Gliding Federation of Australia

At about 1335, the pilot of a Rolladen-Schneider LS3-A glider, registered VH-CQP (CQP), launched from Mount Beauty Airport, Victoria, for a pleasure flight. At about 1355, the glider was 3 to 4 km north-west of the airfield and descending through about 4,000 ft, when the pilot heard an alarm sounding, but did not identify it as issuing from the FLARM collision avoidance system (see FLARM below) fitted to the glider. The glider was tracking to the north, and the pilot reported that they had been keeping a lookout for other gliders but were not aware of any in the vicinity at the time.

The pilot tried to identify the source of the alarm inside the cockpit, which diverted their attention from looking outside. As the pilot became stressed by the noise, particularly as it became ‘quite shrill’, the cockpit fogged up, further reducing the pilot’s ability to see outside.

At that time, GWQ was thermalling and in a right bank at about 40–45°, and had completed four orbits. The front seat pilot sighted a glider approaching from the opposite direction at about the same altitude. They assumed that the glider would join the thermal behind them, in the same direction, and on the opposite side of the orbit, in accordance with normal procedures. The front seat pilot asked the rear seat pilot whether they could see the glider, who responded ‘no’. The FLARM fitted to their glider indicated that there was another glider in close proximity and the rear seat pilot looked outside to see where it was.

The front seat pilot assessed that the approaching glider was not going to manoeuvre to join the thermal or to avoid a collision, so took control of the glider and pushed the stick forwards to descend rapidly. The other glider (CQP) passed overhead.

The pilot of CQP sighted a glider pass below, and estimated there was less than 100 ft vertical separation. Both gliders continued their flight for about another hour after which GWQ landed at Porepunkah and CPQ landed at Mount Beauty without further incident.

Flight data

According to the flight data recorded by the gliders’ flight logger, at 1354:58, CQP was at 3,606 ft and GWQ at 3,523 ft. Four seconds later as the gliders’ paths crossed, CQP was at 3,605 ft and GWQ had descended to 3,458 ft.

FLARM

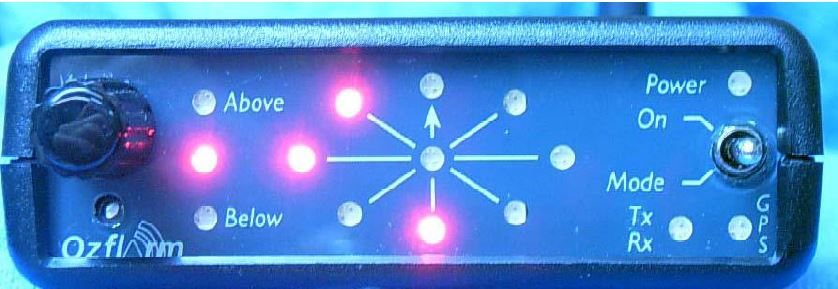

FLARM is a collision avoidance system that shows other similarly equipped aircraft in the vicinity. The display shows the approximate direction of detected traffic and whether it is above, below or at about the same level (Figure 2).

Figure 2: OZflarm display

Source: OZflarm

According to the FLARM website,

Each FLARM device determines its position and altitude with a highly sensitive state of the art GPS receiver. Based on speed, acceleration, heading, track, turn radius, wind, altitude, vertical speed, configured aircraft type, and other parameters, a very precise projected flight path can be calculated. The flight path is encoded and sent over an encrypted radio channel to all nearby aircraft at least once per second.

At the same time, the FLARM device receives the same encoded flight path from all surrounding aircraft. Using a combination of own and received flight paths, an intelligent motion prediction algorithm calculates a collision risk for each received aircraft based on an integrated risk model. The FLARM device communicates this, together with the direction and altitude difference to the intruding aircraft, to the connected FLARM display. The pilots are then given visual and aural warnings and can take resolutive action.

Pilot comments

Pilot of VH-CQP

The pilot of CQP reported that they had flown gliders fitted with FLARM for 7–8 years and had never heard it make a noise before. This may have been because they had never been close enough to another glider to trigger the alarm before. They were briefed and had a briefing note circulated by the gliding club when they were first installed. The pilot did not think there were any other gliders in the vicinity, and did not associate the alarm with FLARM.

The pilot had a VHF radio with the local area frequency selected, but did not make or hear any broadcasts regarding GWQ.

Pilots of VH-GWQ

The pilot in the front seat of GWQ reported that there were some radio broadcasts at the time, mainly from the glider tug pilots in the circuit at Mount Beauty and Porepunkah. They had not made any broadcasts, and had not heard any from CQP.

The pilot in the rear seat commented that the head and shoulders of the pilot in the front seat obscured their vision immediately ahead at the same level. When the FLARM sounded, rather than looking at the display, they looked outside for the other glider.

The pilot in the rear seat further reported that the FLARM unit in CQP had recently been upgraded to a PowerFlarm. This may have included a new display, and also may have been indicating ADS-B transmissions. Changes to display and aural warnings of the FLARM fitted to CQP may have been confusing for the pilot of CQP.

Safety message

The glider pilots reported that see and avoid was the usual means of maintaining separation from other gliders. It was not uncommon to be in close proximity to other gliders, particularly when thermalling. They did not normally broadcast their position or intentions when thermalling, and expected other glider pilots to adhere to standard procedures.

Avoidance systems such as FLARM can enhace safety in non-controlled airspace by detecting conflicting aircraft also fitted with a compatible system. These assist in alerting pilots to the presence of other aircraft and directing them where to look. The ATSB report Limitations of the See-and-Avoid Principle outlines the major factors that limit the effectiveness of un-alerted see-and-avoid. Insufficient communication between pilots operating in the same area is the most common cause of safety incidents near non-controlled aerodromes.

It is essential that when equipment is installed in an aircraft, pilots have an understanding of its operation and are familiar with its characteristics.

The following publications provide valuable and relevant references for glider pilots:

- Operational Safety Bulletin (OSB) 02/12 - Lookout for Glider Pilots

- Operational Safety Bulletin (OSB) 02 14 - See and Avoid for Glider Pilots

Aviation Short Investigations Bulletin - Issue 51

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2016

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________