Safety summary

What happened

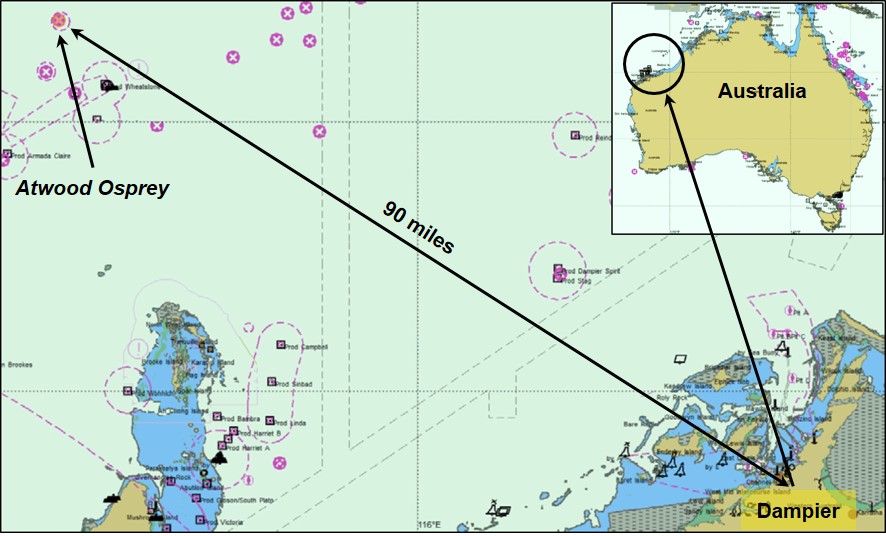

In the early hours of 14 July 2015, the offshore support vessel (OSV) Skandi Pacific was loading cargo containers from the semi-submersible oil rig Atwood Osprey at its offshore location, about 90 miles north-west off Dampier. Shortly after 0505, cargo transfer was stopped due to worsening weather conditions. Skandi Pacific was moved 30 m away from the rig with the rough seas still on its port quarter. Two crewmembers then began securing cargo on the vessel’s aft deck.

While securing the cargo, the crewmembers slackened the securing chain they had used to secure the containers on the starboard side to better secure the entire stow. At about 0523, two large waves came over Skandi Pacific’s open stern, shifting the unsecured containers forward. One of the crewmembers was trapped between the moving containers, chains and a skip and suffered fatal crush injuries.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB investigation found that the risks associated with securing the cargo in the prevailing weather conditions on 14 July had not been adequately assessed. The fatally injured man was standing in a dangerous location near the unsecured cargo containers when they shifted.

The investigation identified that Skandi Pacific’s safety management system (SMS) procedures for working/securing cargo on deck in poor weather were inadequate with no clearly defined weather limits. Further, there were no clearly defined limits for excessive water on deck that necessitated stopping operations, leaving individuals to make difficult, and necessarily subjective, decisions about whether or not to stop work.

The ATSB also found that Skandi Pacific’s managers had not adequately assessed the inherent high risks associated with seas coming over the vessel’s open stern when work, including cargo handling operations, was being undertaken on its aft deck.

What's been done as a result

Proactive safety action by Skandi Pacific’s managers to avoid a similar accident includes improved cargo handling practices across its OSV fleet. Amongst these measures are updated procedures for working in adverse weather and cargo loading, including specific weather condition limits. In addition, existing risk assessments for offloading deck cargo at installations have been updated to include a section on risks associated with securing cargo.

The safety action taken by the vessel’s managers has adequately addressed the safety issues related to cargo handling/securing in adverse weather. The action taken has partially addressed the safety issue with regard to open stern vessels.

Therefore, the ATSB has issued a safety recommendation to the vessel’s managers to undertake further work to better address the risks associated with the use of vessels with open sterns. The ATSB has also issued a safety advisory notice to shipmasters, owners, and operators of OSV’s to highlight the risks posed by the open stern vessels to the industry more broadly.

Safety message

Offshore support vessel operations are inherently high risk because they often occur in exposed locations in a particularly dynamic environment. Multiple factors, including the weather conditions, schedule requirements, time of day, limited crew numbers, restrictions due to vessel design and systems, amongst others, add complexity to operations. Therefore, risk assessments are critical, with the weather and its impact on factors, such as an open stern, invariably a vital consideration.

At 1515[1] on 7 July, Skandi Pacific (Figure 1) sailed from the Port of Dampier with a cargo for the semi-submersible oil rig, Atwood Osprey (Figure 2), about 90 miles[2] north-west of Dampier.

Figure 1: Skandi Pacific and Figure 2: Atwood Osprey

Source: DOF Management Source: Atwood Oceanics

At about 0600 on 8 July, Skandi Pacific arrived on location at the rig. The vessel was scheduled to carry out cargo handling operations over the following days. Throughout that time, the vessel’s master and mates maintained a two person, 6-on/6-off schedule for navigational watches.

Over the next few days, Skandi Pacific cargo handling operations were conducted with the vessel in Dynamic Positioning[3] (DP) mode.

The wind throughout this time was from the south-southeast at force[4] 5 to 6 (17 to 27 knots).[5]

On July 10, the weather deteriorated and winds increased to force 8 to 9 (34 to 47 knots) preventing Skandi Pacific from carrying out cargo handling operations. The adverse weather conditions continued over the following days and the vessel remained on standby off the rig.

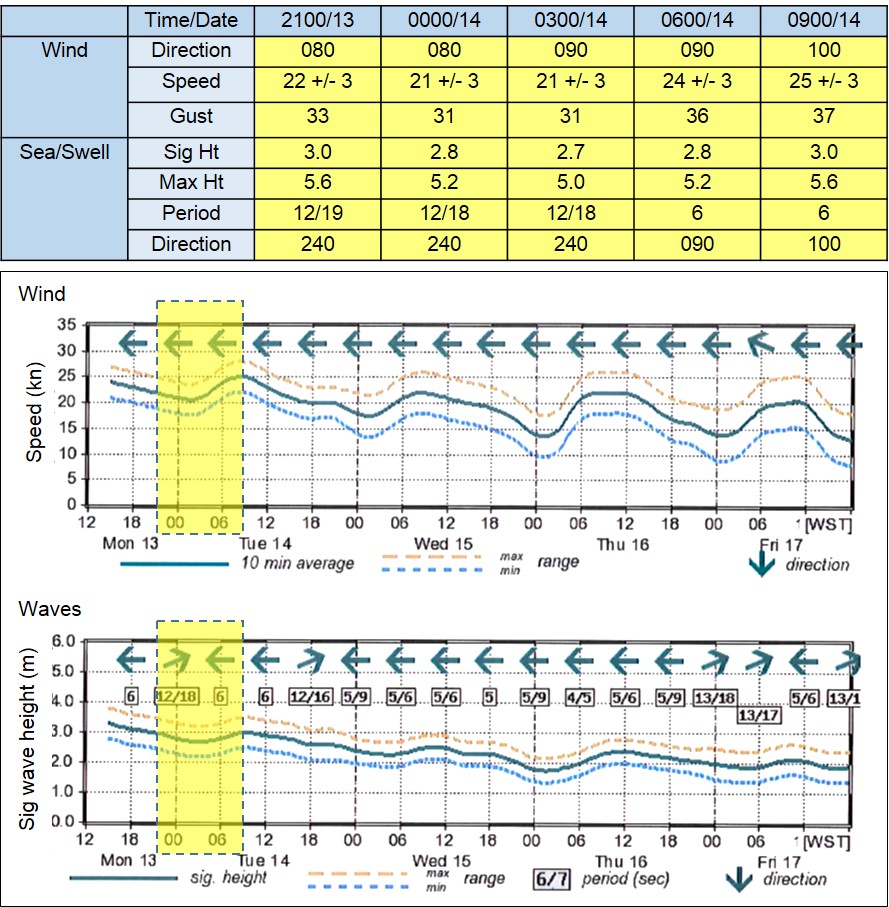

On 13 July, Skandi Pacific’s master received Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) reports, including its commercial weather services report, forecasting that conditions would ease temporarily during the early morning of 14 July.

During the 1800-2400 watch on 13 July, Skandi Pacific was standing off the rig. The master noted in his night orders that cargo handling operations were due to commence after another offshore support vessel (OSV) had departed. In his orders, he also stated that ‘the weather was due to deteriorate again so keep this in mind’.

At 0010 on 14 July, the rig’s controller called Skandi Pacific’s master and instructed him to move into the 500 m exclusion zone off the rig and prepare to backload cargo (cargo transfer from the rig to the vessel). Shortly after, the master handed over the watch to the chief mate. The master then remained on the navigation bridge (bridge) and conducted a toolbox talk[6] for the cargo work with the chief mate, second mate, and the two integrated ratings[7] (IR) who were to be on deck during cargo work.[8] This talk included instruction for crush hazard awareness, backloading cargo in block stows, escape routes and for the IRs to stop work if seas were shipped on deck.

Shortly thereafter, the master left the bridge. At that time, the wind was easterly at 15 to 25 knots with 2 to 3 m seas, consistent with the weather forecast.

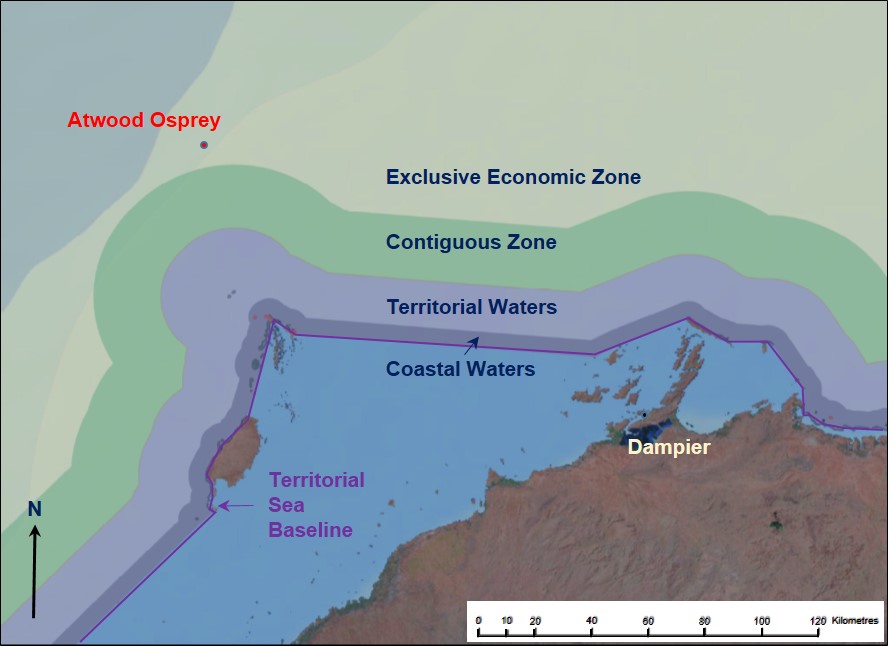

Figure 3: Dampier and position of the Atwood Osprey

Source: Australian Hydrographic Service with ATSB annotations

At about 0025, Skandi Pacific’s chief mate moved the vessel closer to the rig, as planned, and placed it in DP mode. At 0045, after completing the DP checklist, he began moving it under the rig’s loading platform, which was on its leeward side. At about this time, the master briefly returned to the bridge. He noted the weather as acceptable for the operations, with occasional sea spray on deck.

By 0105, the chief mate completed the move and the two IRs were already on deck, releasing lashings in preparation for backloading empty mini-containers, open top containers and 10-foot sea containers from the rig.

At 0140, backloading of containers from the rig started and from time to time, there was spray across Skandi Pacific’s deck. The vessel’s motion in the seas meant that it moved around its position under the loading platform, but the DP system kept it within the set range (2 m) and on a true heading[9] of between 237° and 238°.

Shortly before 0200, the IR starting his watch came to the bridge for the toolbox talk and signed the briefing form. He then proceeded to the aft deck and the IR completing the 2000-0200 watch handed over to him and left the deck.

At 0400, the wind was recorded in the vessel’s deck log book as northeast force 5 to 6 (17 to 27 knots). The sea state was recorded as 5 (that is, wave height 2.5 to 4 m or rough seas). In those weather conditions, waves were occasionally shipped on deck over the vessel’s open stern. This became more frequent over the next hour and, in the minutes before 0500, some bigger waves washed across a large part of the aft deck.

At 0501, the second of two mini-containers was landed at the forward part of the aft deck on the starboard side. The IRs released the crane hook from the container and moved clear. Between 0502 and 0503, two waves were shipped on deck in succession as the vessel pitched with the water washing forward about 40 m across the port side of the aft deck.

At 0503, the DP status alarm triggered indicating that Skandi Pacific had moved outside the set limit of 4 m. The chief mate informed the rig that it was ‘too rough’ with the vessel getting pushed ‘further out of position’ and ‘more and more water’ coming on deck, making it ‘dangerous’ for the operations and the men on deck. He asked the rig to stop backloading and then advised the IRs that the operations had been suspended. The deck log book entry stated ‘0505 Stop Job, weather increasing in strength’. Shortly after 0505, another large wave came over the stern.

By 0507, the chief mate had stepped Skandi Pacific about 30 m to leeward of the rig. The vessel remained in DP mode and on the same heading. He then instructed the IRs to lash the containers on deck.

Shortly thereafter, the two IRs moved aft to start lashing the containers. From the chief mate’s seated position at the DP console, facing aft, he could see the men as they moved around the aft end of the deck. They first lashed the cargo platforms on the port side with chains, run from the crash barrier at the stern of the vessel around the platforms. The chains were attached at the forward end of the deck to a tugger wire[10] and tensioned with the port tugger winch.

By 0511, the IRs had completed lashing on the port side. During this time, a couple of smaller waves had been shipped on deck.

At 0512, the IRs moved to the starboard side cargo stow, which included open top, mini and 10-foot sea containers. They moved between the vessel’s stern and the forward part of the stow. A few smaller waves came over the stern during this time.

By about 0518, the IRs had lashed the cargo stow using the starboard winch to heave the tugger wire (in a similar manner to the port side) to tension the chains rigged around the containers. They then began checking the lashings starting from aft. At 0519, while they were aft at the starboard quarter, a wave came over the port quarter and washed across the port side.

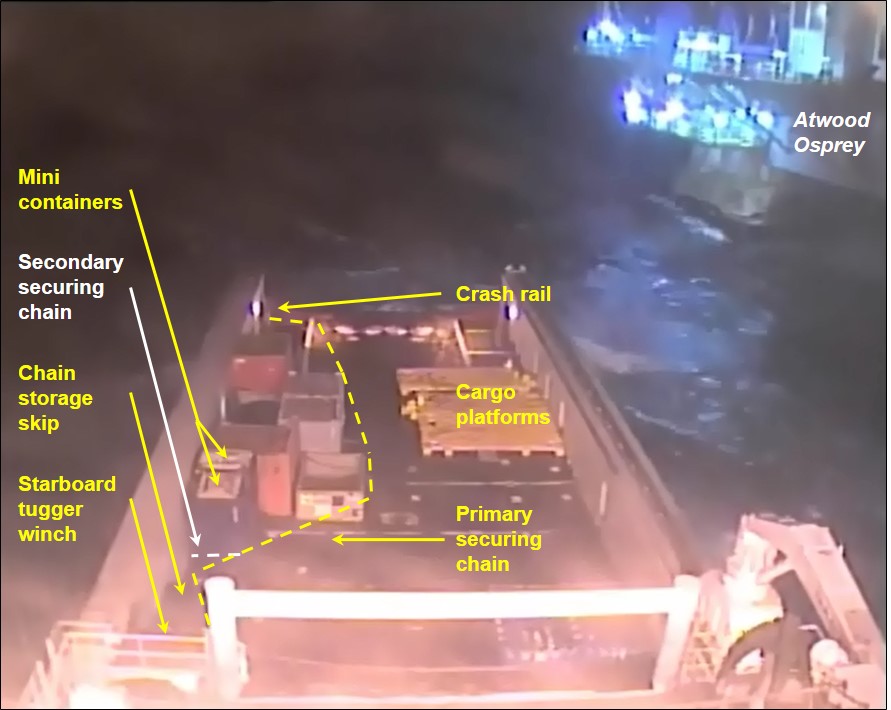

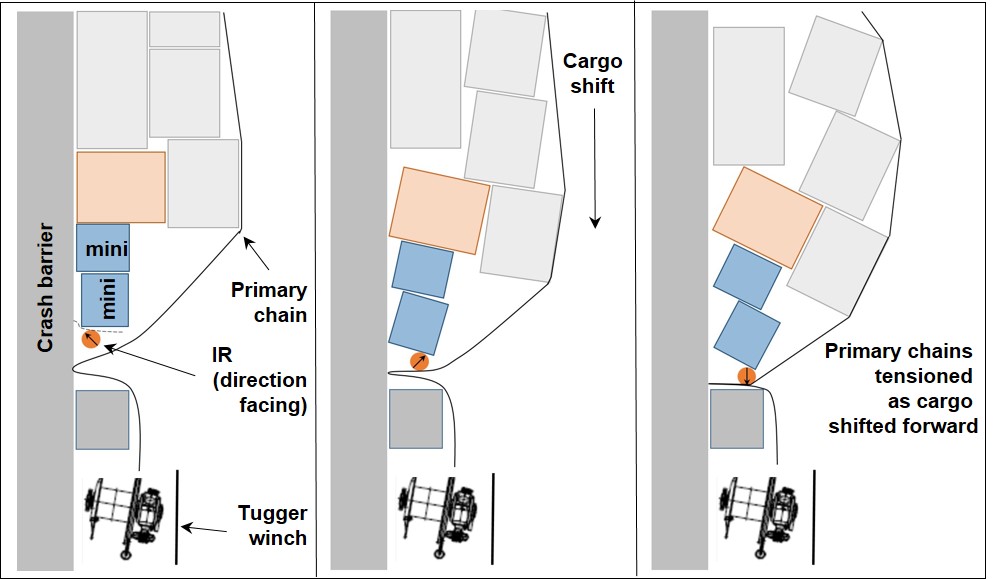

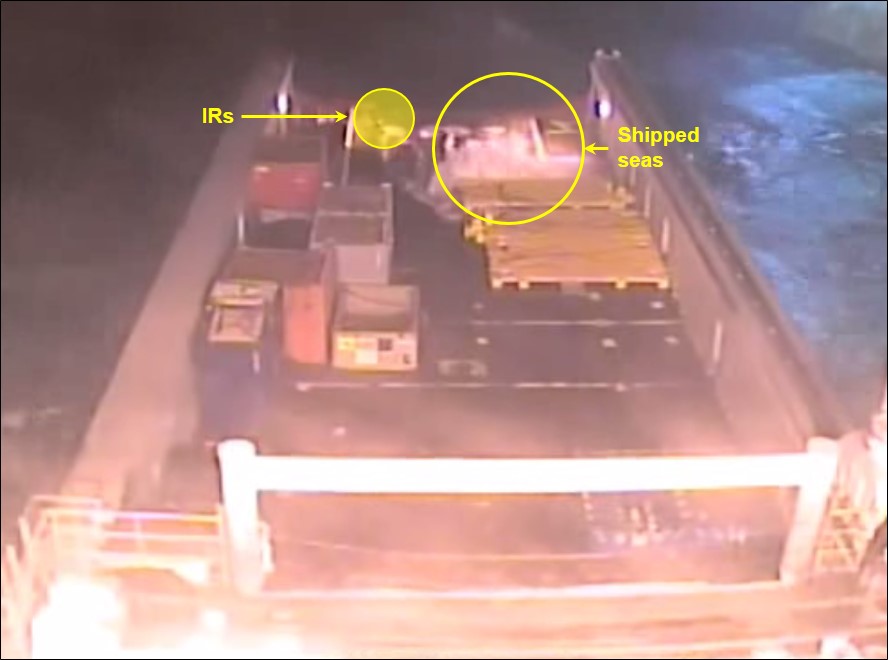

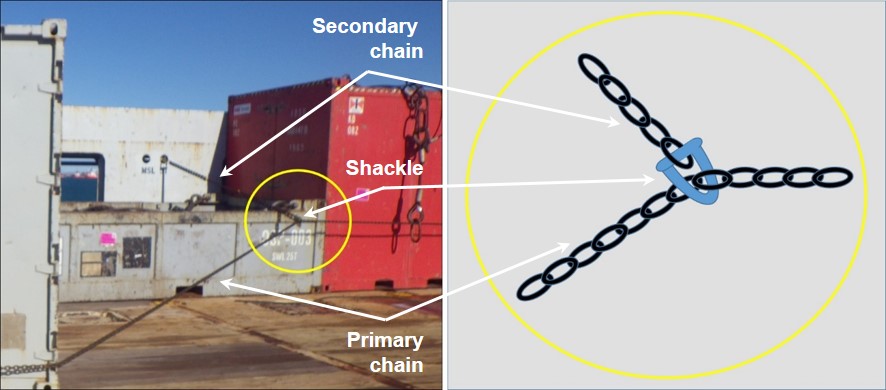

At about 0520, when the IRs checked the forward part of the stow, they found the two forward mini-containers were not properly secured by the primary chain. They decided to secure them using a secondary chain secured to the crash barrier between the mini-containers and the skip, and then to the primary chain (Figure 4). When tightened, the secondary chain would tighten the primary chain against the mini-containers. That would require the primary chain to be slackened off (tensioned down – the term used on board the vessel).

Shortly thereafter, the tugger wire was payed out, which again unsecured the entire starboard cargo stow. No one informed the mates on the bridge that the primary chain had been tensioned down.

The IRs began rigging the secondary chain forward of the mini-containers. They decided to use a shackle looped around the primary chain and secured to the end of the secondary chain. This arrangement would allow the shackle to run along the primary chain and keep the tension in it.

At 0522, both IRs were preparing the secondary chain. Thirty seconds later, one IR went forward to the nearby store to get the shackle, leaving the other to connect the chain to the crash barrier.

Figure 4: Skandi Pacific’s aft deck securing chain arrangement

Source: Skandi Pacific’s CCTV at 0521 on 14 July 2015 (annotated by ATSB)

Moments before 0523, a large wave came over the stern and washed across the deck. The water on deck had not yet receded, when a larger wave came over the stern. From his position on the bridge, the chief mate had seen the seas coming over the stern and called out a warning to the men on deck over the UHF radio. The IR getting the shackle had the UHF radio while the one rigging the secondary chain had the VHF radio.

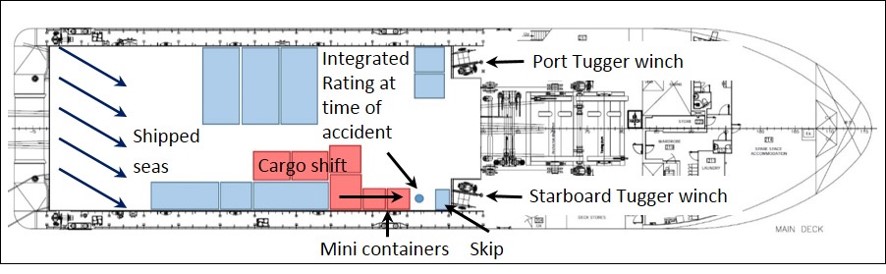

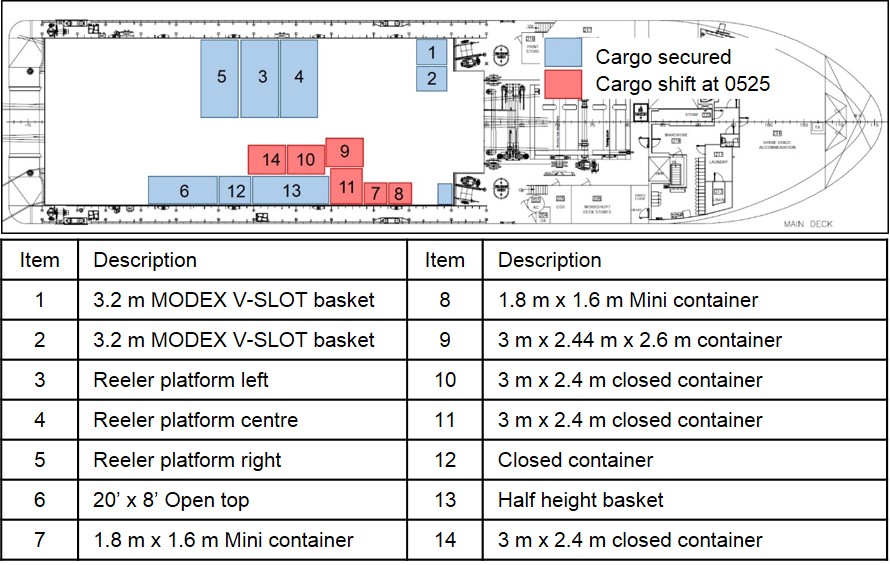

At 0523,[11] as the large quantity of water washed forward along the deck, it shifted some of the starboard side cargo containers (Figure 5) and continued as far forward as the Skandi Pacific’s superstructure. The IR rigging the secondary chain just forward of the mini-containers tried to move clear of the advancing containers but did not have enough time to get clear. He was trapped in between the forward mini-container and the primary chain, and was crushed against a skip.

Figure 5: Aft deck plan showing stowage and other key positions

Source: DOF Management (annotated by ATSB)

The IR returning with the shackle heard the warning over his radio. When he reached the mini-containers, he saw the injured man. He immediately called the bridge and informed the chief mate that the other IR had been injured. The chief mate told the second mate on watch with him to call the master, and to take over the DP console. He then went to the accident area.

Shortly thereafter, the master arrived on the bridge, and the second mate informed him that an IR was pinned between the deck cargo. The master called the rig, advised that there had been an accident and requested medical assistance.

At 0527, the master sounded the general alarm followed by a public address to muster all crewmembers at their stations. He also asked the rig to arrange a helicopter for a medical evacuation

A short while later, the chief mate and other crewmembers freed the IR, who was unresponsive. The crewmembers then started cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) on the seriously injured man and the master manoeuvred Skandi Pacific under the rig’s loading platform.

At 0605, three crew from Atwood Osprey, including two medics boarded Skandi Pacific. They continued CPR and moved the injured IR onto a stretcher in preparation for transfer to the rig.

At 0613, the injured IR was transferred to Atwood Osprey. He was then taken to the rig’s hospital, where, at 0630, the medics declared him deceased.

__________

- All times referred to in this report are local time, Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) + 8 hours.

- A nautical mile of 1852 m.

- Dynamic Positioning is a computer-controlled system to automatically maintain a vessel's position and heading by adjusting its propulsion units to suit the weather and sea conditions.

- The Beaufort scale of wind force, developed in 1805 by Admiral Sir Francis Beaufort, enables sailors to estimate wind speeds through visual observations of sea states.

- One knot, or one nautical mile per hour equals 1.852 kilometres per hour.

- The toolbox talk communicates the risk assessment and specific controls to the work party.

- Integrated ratings are qualified to perform the duties of both an able seaman and an engine rating.

- The IRs’ working hours consisted of sea watches, plus 2 hours either before or after their watch during cargo operations. On 13/14 July, the three IRs work routines were 2000-0200, 0000-0600 and 0200-0800. Additionally, a day work IR was available from 0600-1800.

- All ship’s headings in this report are in degrees by gyro compass with negligible error.

- Relatively small (15-20 mm) diameter wires, stowed on their own winches, one each side at the forward end of the working deck. The direction of pull is facilitated by passing the wires through snatch blocks, which can be secured in various places along the working deck.

- The accident was recorded in the vessel’s deck log book at 0525, some 2 minutes later than the CCTV footage.

Skandi Pacific

At the time of the accident, the anchor handling tug supply (AHTS) vessel, Skandi Pacific, was registered in the Bahamas, classed with Det Norske Veritas (DNV) and managed by DOF Management, Norway. The vessel was under charter to Chevron Australia to facilitate support operations for the semi-submersible oil rig, Atwood Osprey.

As an offshore support vessel (OSV) Skandi Pacific was designed for offshore operations including anchor handling and towing, and had a multi-national crew of 12, including the master. The master had 20 years of seagoing experience, including 5 years as master on OSVs. He had been assigned to the vessel for the past 2½ years and had joined it about 2 weeks before the accident.

The chief mate had 14 years of seagoing experience, including 7 years on offshore support vessels. He had been chief mate on Skandi Pacific for 1½ years as chief mate and had joined about 2 weeks before the accident.

The Integrated Ratings (IR) on deck at the time of the accident were suitably qualified in their respective ranks. Both IRs had experience at this rank on board OSVs and had joined Skandi Pacific about 2 weeks before the accident.

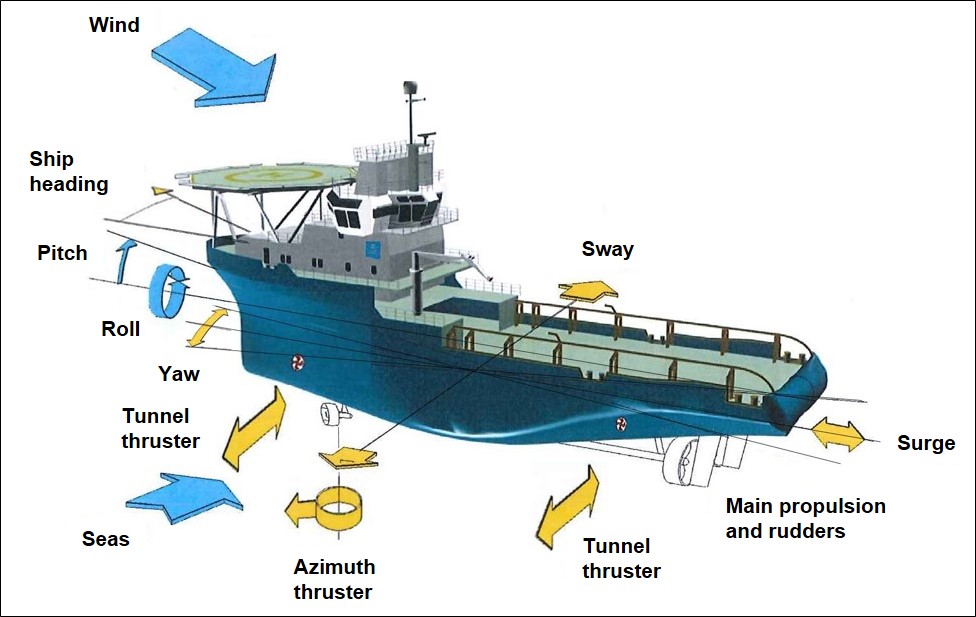

DP system

A computerised Dynamic Positioning (DP) system uses the vessel’s thrusters and propellers to control its position and heading. The DP system automatically adjusts the propulsion units to counteract the environmental forces (Figure 6) to keep the vessel on location at, or very near to a specified position.

Figure 6: Vesselpropulsion, thrusters, movement and external forces

Source: DOF Management (annotated by ATSB)

Accurate measurement of the vessel’s position at any point in time is necessary for precise DP. Additionally, as the vessel is subject to wind, wave and current forces, these forces also need to be accurately measured by the DP system. The system then controls the vessel’s motion in the three horizontal degrees of freedom:

The position reference systems consist of DGPS[15], RADius[16] and Fanbeam,[17] of which all three reference systems are required for DP class 2[18] operations.

Skandi Pacific was equipped with two stern thrusters, two bow thrusters and two controllable pitch propellers, designed to comply with a DP equipment class two system. The vessel’s position could also be maintained manually by using a single joystick to control all thrusters.

When the vessel was operating in DP mode, its status could be one of the following:

- Green status: normal operation indicating the position and heading were within predetermined limits.

- Yellow status: degraded DP control indicating position keeping was deteriorating and/or unstable (moving 2 m from the set position) and weather conditions becoming unsuitable for DP operation (the DP operator or DPO,[19] master and rig supervisor should then discuss continued operations).

- Red status: indicating a DP emergency triggered by either by a system failure or external condition, preventing the vessel maintaining its position within 4 m from the set position.

Annual DP trial programme

Annual DP trials are a thorough test of a DP system to verify its capability and performance and to confirm it has been maintained in accordance with international requirements. Further, all major DP systems and sub-systems are tested to determine the ability of the vessel to maintain position after single system failures,[20] associated with the assigned equipment class.

These tests confirm that the ‘failure modes and effects analysis’[21] conducted during the design process of the vessel is still valid. Any new equipment or system upgrades are incorporated in all trials to ensure they react as intended.

DP capability plot

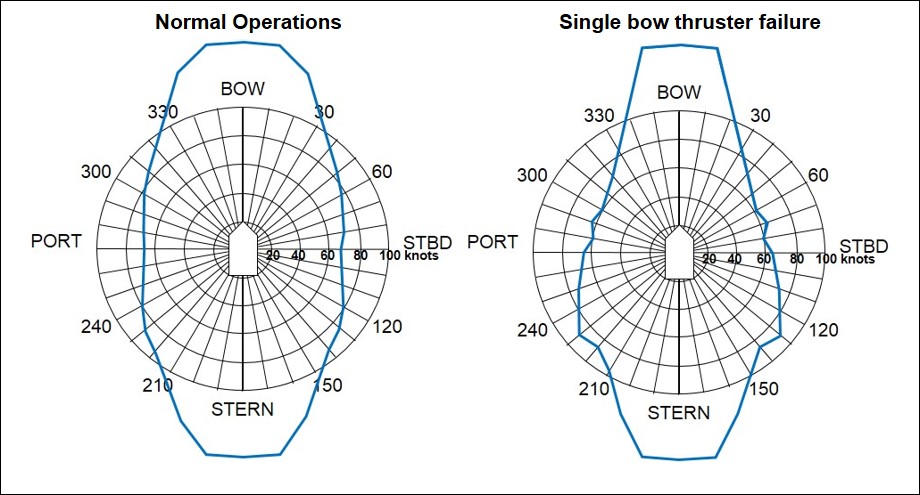

DP capability defines a vessel’s ability to remain in position under given environmental and operational conditions. The capability plots (Figure 7) are calculated for normal operation and for DP system failures, such as a loss of thruster, including worst case failures.

These plots are not of actual performance, but are based on calculations and provided by the manufacturer of the DP system. The calculated DP capabilities of the vessel can be used to determine if the vessel will remain in position during DP operations in the prevailing or forecast weather conditions.

Skandi Pacific’s DP capability plots (Figure 7) show the ‘normal operations’ and ‘single bow thruster failure’. The plots show the limiting wind speed 360 degree envelopes (blue line), where each point on the envelope represents the wind speed at which it is calculated that the vessel will be unable to maintain position in DP mode. With a single bow thruster failure, the vessel had reduced capability when winds exceeded 60 knots.

Figure 7: Skandi Pacific's DP capability plots

Source: Skandi Pacific (annotations by ATSB)

DP system check

Offshore facilities are protected by the establishment of an exclusion safety zone[22] around the structure and entry into the exclusion safety zone is controlled by the facility.

Prior to entering the exclusion zone at any facility, all vessels are required to complete a pre-entry checklist. The purpose is to ensure satisfactory operation of the vessel’s DP system, including full functional checks of the operation of the thrusters, power generation, automatic DP and joystick/manual control.

Additionally, when departing the facility, the vessel is to be manoeuvred well clear of the facility before changing operating modes. The Guidelines for Offshore Marine Operations (G-OMO)[23] recommend that this distance is usually between 1½ to 2½ vessel lengths, depending on the drift conditions.

Operational risk management

The DOF Management operational risk management procedures are mainly based on best practice and the G-OMO. These procedures included the following guidance.

Risk assessment

Risk Assessments (RA) are used to identify and then mitigate risks to an acceptable level. If the risks cannot be mitigated to an acceptable level, the work should not proceed.

The RAs on board Skandi Pacific included details of the task, the team members, activity description, identified hazards, the effects of those hazards, existing controls and additional control measures.

Toolbox talks

A toolbox talk (TBT) is a meeting of the personnel involved in an imminent task to review the task, individual responsibilities, equipment required, competency of the individuals, hazards, and any RAs in place.

On board Skandi Pacific, all personnel involved in cargo handling operations attended TBTs. The objective was to communicate the RA and to capture any additional controls not already identified. This included (but was not limited to):

- individual roles

- tools, methods and procedures to be used

- a review of the RA

- promote the ‘stop the job’[24] culture.

Management of change

The company had a management of change (MOC) process in place for all tasks. This process was used when unexpected changes in circumstance occurred before or during the course of the task. It was then used to identify the change type, details, criticality and what action was required now that the change had occurred. The task would not continue until the implications of that change were reviewed. If appropriate, the RA would be reviewed before resumption of the task and a TBT carried out. For example, the loss of the use of a bow thruster on board Skandi Pacific changed the operational capability of the vessel. Therefore the MOC process was used to define and assess subsequent operational limitations.

Cargo stowage and securing

There are many sources of relevant guidance for cargo handling on board OSVs. The International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) Resolution A.863(20)[25] states the following for OSVs with an open stern:

vessels are provided with instructions to counter dangerous situations if cargoes with a tendency to float and/or with low friction coefficients are stowed on the exposed deck

the number of cargo handlers should be sufficient for safe and effective cargo operations

the crew of OSVs should be adequately trained

safe havens and escape routes for personnel from the cargo deck should be properly marked and kept clear at all times. A crash barrier, fitted along each side of the deck, could be one method of achieving a safe haven.

Further guidance is contained in Regulation 5, Chapter VI, SOLAS[26] (Stowage and securing) which specifically references all cargoes, cargo units and cargo transport units shall be loaded, stowed and secured in accordance with the Cargo Securing Manual (CSM).

The Cargo Securing Manual[27] (CSM) is to include information on a number of pre-identified items:

details of fixed securing arrangements and their locations

examples of correct application of portable securing gear on various cargo units, carried on the vessel.

Skandi Pacific’s CSM contained the above procedures for cargo handling alongside installations and included the following guidance for open stern AHTS vessels:

Open stern anchor handling vessels require special care, especially with regards to freeboard. Consideration should be given to the open stern being physically barriered. Use RA and TBT to minimise crew or cargo exposure to elements, particularly when working with the stern towards the weather.

Additionally, the IMO Resolution A.717(17), Code of Safe Practice for Cargo Stowage and Securing, states:

The proper stowage and securing of cargoes is of the utmost importance for the safety of life at sea. Improper stowage and securing of cargoes has resulted in numerous serious vessel casualties and caused injury and loss of life, not only at sea but also during loading and discharge.

Maritime boundaries

In 1994, the Australia government ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and became legally bound to its provisions. As such, Australia is bound to follow UNCLOS rules for maritime boundaries, access to the various marine zones and managing the resources and activities within those boundaries.

Figure 8: Maritime boundaries off the North West Shelf, Western Australia

Source: Geoscience Australia (annotated by ATSB)

To determine the maritime boundaries (Figure 8) requires the delineation of the Territorial Sea Baseline[28] (TSB). The TSB is the line from which the outer limits of a number of maritime zones are calculated and include the:

- 3 nautical mile limit of the coastal waters[29]

- 12 nautical mile limit of the territorial sea[30]

- 24 nautical mile limit of the contiguous zone[31]

- 200 nautical mile limit of the Australian Exclusive Economic Zone.[32]

Jurisdiction

The Offshore Constitutional Settlement (OCS) is an agreement between the Commonwealth and the States, which provides the basis for an agreed division of powers in relation to coastal waters and other matters. These include the regulation of shipping and navigation, offshore[33] petroleum exploration, crimes at sea, and fisheries.

National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority

The National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority’s (NOPSEMA) functions and powers are derived from the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006 (OPGGS Act) and associated regulations. The OPGGS Act provides that NOPSEMA is charged with regulating health and safety, well integrity and environmental management for all offshore petroleum facilities and activities in Commonwealth waters.[34] Additionally, it has similar functions where State and Territory powers to regulate have been transferred, covering the area within the first three nautical miles for coastal waters.

The Australian Maritime Safety Authority

The Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) is charged with the responsibility for ensuring the safety of Australian flagged vessels and foreign flagged vessels in Australian ports and waters, and the seafarers on board. International and national conventions and regulatory frameworks provide the standards enforced by AMSA to achieve safety outcomes.

According to AMSA, it delivers necessary safety outcomes through inspections such as those under Port State Control, flag State requirements, Cargo, Maritime Labour Convention, and Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) when the ship is in port.

Trained AMSA OHS inspectors perform investigations of accidents and dangerous occurrences on ‘prescribed ships’[35]:

- in an Australian port

- entering or leaving an Australian port

- in the internal and territorial waters of Australia.

Skandi Pacific was not covered under the above requirements and, hence, Australian OHS legislation did not apply to the vessel.

Memorandum of Understanding between AMSA and NOPSEMA

The Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the two authorities provides for the cooperation of both parties in the administration of their respective commitments including audits, inspections and accident investigations of offshore facilities. It delivers a consistent and comprehensive regulatory regime in offshore waters and avoids duplication in respect of vessels and facilities where the two organisations have regulatory obligations. The MoU was last revised in 2013, when AMSA and NOPSEMA agreed to further joint inspections of floating facilities.

At the time of the accident, Skandi Pacific was not engaged in cargo handling operations with Atwood Osprey. The vessel was also outside the territorial waters of Australia. Its location and status meant that it was outside the jurisdiction of both NOPSEMA and AMSA.

Safety investigations

The IMO’s Casualty Investigation Code is mandatory under SOLAS and requires the flag State[36] of a vessel to conduct a marine safety investigation into every ‘very serious marine casualty’.[37] The Bahamas, as the flag State of Skandi Pacific was obliged to investigate the fatal accident on 14 July. The Bahamas Maritime Authority commenced a safety investigation under their national legislation.

The ATSB, as a substantially interested State,[38] also commenced a safety investigation.

Similar past accidents

The ATSB’s predecessor, the Marine Incident Investigation Unit (MIIU), investigated a similar fatal accident on board an OSV in 1995.

Shelf Supporter was a 1985-built OSV equipped with a DP system. The vessel had a large, clear aft deck that enabled it to carry stores and equipment to/from offshore facilities. It operated off the north-west coast of Australia.

At about 0550 on 29 December 1995, Shelf Supporter’s master manoeuvred the OSV to approach an offshore platform’s crane position with its bow in (that is, stern to sea). It had cargo on the aft deck, which had been secured by the vessel’s crewmembers using tugger wires and winches.

Shortly after 0600, two crewmembers went out to the aft deck to prepare for unloading cargo. They released the tugger wires and re-spooled the starboard wire onto the winch drum. However, before they could re-spool the port wire, the vessel arrived under the crane and its lifting hook was lowered just above their heads. They left the port wire flaked on deck, and hooked on the first lift.

On the bridge, the master was maintaining the vessel’s position and saw a wave breaking over the stern. He broadcast a warning to the two men on deck. As the water ran up the deck, he saw one of the men just forward of a skip. He then saw the skip move forward and crush the man against another skip.

The following summary of some of the MIIU’s findings is particularly relevant:

- OSVs frequently work in moderate and even rough seas. Their design with a long low aft deck, generally with no protective stern bulwark makes seas breaking over the stern common place.

- Sea conditions at the time of the accident were not such as to warrant cancelling operations.

- Although a warning may be called out to crewmembers on deck, they have little time to react. If a sea breaks over the stern and they do not see it approaching, their reactions must be instinctive.

- The securing of cargo in block stows with the tugger wires is common practice in the offshore industry. It is simple and easy to set up and quick to release. However, it has a big disadvantage because once removed, all of the deck cargo is unsecured until discharged.

In June 2016, the International Marine Contractors Association (IMCA)[39] promulgated details of a recent incident involving cargo shift on an OSV’s aft deck in heavy weather while alongside a platform.

The OSV was engaged in cargo handling operations with its starboard quarter to the weather when it experienced a sudden and unexpected squall. A large wave was shipped and flooded the aft deck. The water shifted one container and turned another one over. The backloaded containers had not yet been secured due to on-going backloading. Fortunately, no one was injured.

The lessons learned included:

- The risk of abnormal waves should be taken into consideration in risk assessments and tool box talks for work, particularly when the vessel is positioned stern to the weather

- Greater emphasis should be placed on the ‘stop work policy’ – anyone should be able to stop the job, any time, when in doubt

- A new and higher bulwark to be fitted to the vessel and other similar vessels.

__________

- The bodily motion of a ship in a seaway forward and back along the longitudinal axis.

- The side-to-side bodily motion of a ship in a seaway, independently of rolling, caused by a uniform pressure being exerted all along one side of the hull.

- The horizontal oscillation of a ship about a vertical axis approximately through its centre of gravity.

- Differential Global Positioning System.

- RADius is a short distance reference system consisting of transponders installed as targets, in this case on the platform and sensors on the OSV vessel.

- Fanbeam is a short range laser scanning radar system.

- DP equipment Class 2 has redundancy so that no single fault in an active system will cause the system to fail. Loss of position should not occur from a single fault of an active component or system such as generators, thruster, switchboards, remote controlled valves etc.

- The designated watchkeeping officer responsible for managing the dynamic positioning of the vessel.

- Single failure criteria include any active component or system (such as generators, thrusters, switchboards or remote controlled valves), together with any normally static component (such as, cables, pipelines or manual valves) that cannot be shown to have adequate protection from damage or have proven reliability.

- A systematic analysis of the systems to demonstrate that no single system failure will cause an undesired event.

- Established within a radius extending to a distance determined by the relevant legislations beyond the outline of any installation, excluding submarine pipelines (NOPSEMA).

- The G-OMO provides guidance in the best practices which should be adopted to ensure the safety of personnel on board all vessels servicing and supporting offshore facilities, and to reduce the risks associated with such operations.

- Stopping The Job is one in which everyone has the right to stop the job, the duty to stop the job and the moral responsibility to stop the job.

- The Code of Safe Practice for the Carriage of Cargoes and Persons by Offshore Support Vessels (OSV Code).

- The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, 1974, as amended.

- IMO Resolution A.489(XII), adopted on 19 November 1981, Safe Stowage And Securing Of Cargo Units And Other Entities In Ships Other Than Cellular Container Ships Cargo Securing Manual.

- The TSB corresponds with the low water line along the coast, including the coasts of islands. The baseline can be drawn around low tide elevations which are defined as naturally formed areas of land surrounded by and above water at low tide but submerged at high tide, provided they are wholly or partly within 12 nautical miles of the coast. For Australian purposes, the baseline corresponds to the level of Lowest Astronomical Tide (LAT)

- Coastal Waters is a belt of water between the limits of the Australian States and the Northern Territory and a line 3 nm seaward of the territorial sea baseline. Jurisdiction over the water column and the subjacent seabed is vested in the adjacent State or Territory as if the area formed part of that State or Territory.

- The Territorial Sea is a belt of water not exceeding 12 nm in width measured from the territorial sea baseline. The major limitation on Australia's exercise of sovereignty in the territorial sea is the right of innocent passage for foreign ships.

- The Contiguous Zone is a belt of water contiguous to the territorial sea, the outer limit of which does not exceed 24 nm from the territorial sea baseline.

- The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) is an area beyond and adjacent to the territorial sea. The outer limit of the EEZ cannot exceed 200 nm from the baseline.

- An offshore area starts 3 nm from the TSB from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured and extends seaward to the outer limits of the continental shelf.

- The Commonwealth marine area is any part of the sea, including the waters, seabed, and airspace, within Australia’s exclusive economic zone and/or over the continental shelf of Australia, that is not State or Northern Territory waters.

- A prescribed ship is a ship registered in Australia, a ship engaged in coastal trading, a ship on which the majority of crewmembers are residents of Australia and which are operated by persons or firms which have their principal place of business in Australia or a ship declared by the Minister to be a prescribed ship.

- Flag State means a State whose flag a ship is entitled to fly.

- A very serious marine casualty means a marine casualty involving the total loss of the ship or a death or severe damage to the environment.

- A substantially interested State means a State where, as a result of a marine casualty, nationals of that State lost their lives or received serious injuries.

- The IMCA is a trade association representing companies and organisations engaged in delivering offshore, marine and underwater solutions.

The accident

At 0505 on 14 July, Skandi Pacific’s chief mate stopped backloading after the vessel’s DP system was no longer able to maintain its positon within defined parameters in the deteriorating weather conditions. In the rough seas, waves were regularly coming on deck over the vessel’s open stern.

By 0507, the chief mate had stepped Skandi Pacific out, to about 30 m off the rig on its leeward side, in DP mode. He then instructed the IRs to lash the containers on the aft deck.

At about 0520, after the IRs had lashed the cargo they found two mini-containers on the starboard side forward, not properly secured by the primary chain. In order to better secure the containers, the IRs decided to use a secondary chain secured to the crash barrier and then to the primary chain. Tightening the secondary chain would tighten the primary chain against the mini-containers. Their plan required tensioning down the tugger wire (and hence the primary chain). When they slackened the chain, the block of cargo on the starboard side was unsecured.

At 0523, two large waves came over the vessel’s stern in quick succession, shifting the unsecured containers on the starboard side. Their movement caused the primary chain to tension (Figure 9). As a result, the slack chain was lifted up, blocking the escape route of the IR who had stepped inside the primary chain to secure the secondary chain to the crash barrier. Although he tried to move clear of the advancing containers, in the few moments he had (to get clear) his escape (route) was impeded by the chain and he could not get clear.

Figure 9: Diagrams to illustrate the event sequence leading to the accident

Source: Cargo manifest (annotated by ATSB)

Prevailing weather conditions

At 1500 on 13 July, a BoM weather forecast (Figure 10) was issued for the general area where the Atwood Osprey platform is located:

A high is stalling over the southwest coast of WA. The ridging associated with the high will keep a relatively tight E/SE’ly pressure gradient over the Pilbara and adjacent waters. Expect fresh to strong winds through the forecast period.

Monday 13 July Confidence High, Partly Cloudy

- Mean winds 25/30 knots (possibly up to 32 knots)

- Total wave 3.1 m to 3.5 m (possibly up to 4.0 m)

Tuesday 14 July Confidence High, Partly Cloudy, Mostly sunny

- Mean winds 23/28 knots (possibly up to 32 knots)

- Total wave 2.6 m to 2.9 m (possibly up to 3.5 m)

The forecast showed a temporary lull in the wind speed and sea/swell conditions during the early hours of the following day, 14 July.

Figure 10: BOM’s commercial weather services forecast for 13/14 July 2015

Source: Skandi Pacific

Later in the afternoon on 13 July, another OSV started cargo handling operations on the lee side of Atwood Osprey. Shortly after 1800, the rig’s controller instructed Skandi Pacific’s master that his vessel would be called in next, about midnight, after the other vessel had departed.

The master continued monitoring the weather conditions throughout his 1800-2400 watch. The DP capability plot (Figure 7) also indicated that the vessel could maintain position in the conditions. Therefore, he noted in his night orders to the watchkeeping officers:

Make sure you are happy with position keeping and vessel movement before starting any ops.

There is quite some backload.

Stow as well as possible i.e. good blocks to secure for transit back to port. Weather is due to deteriorate again so keep this in mind.

Call me if in doubt.

Standing orders apply.

Skandi Pacific’s CSM provided guidance based on G-OMO, which is considered to be the best practice for offloading and backloading cargo alongside offshore installations, including:

Weather Conditions

- Weather conditions must be appropriate for the operation

- Always stop work in adverse weather conditions

- Comply with relevant guidelines on weather criteria.

However, consideration of the weather conditions and what could be deemed ‘adverse weather’ is subjective. Further, the company’s safety management system (SMS) did not provide any clearly defined guidance on weather limits for undertaking deck cargo handling operations or triggers to stop operations. The only such guidance was contained in Skandi Pacific’s charterer’s marine operating guidelines for bulk cargo operations:[40]

Weather Limit Guidelines

Provided proper preparations have been made, the appropriate bulk transfer checklist has been completed and all other factors considered and found favourable, the following weather limits are recommended for conducting bulk transfers between vessels and an offshore facility:

- Wind < 30 knots / 15 m/s

- Sea < 3 metres (significant wave height)[41]

The master used these guidelines to determine that the cargo handling operations could proceed. At midnight on 13 July, the forecast weather conditions (wind speed and significant wave height) were within the above weather limits.

The company’s SMS did not contain any clearly defined limits or parameters for cargo handling operations in adverse weather conditions. To determine if the conditions were appropriate for operations was at the discretion of the master. On 14 July, one of the conditions that he stipulated was to stop work if there was water on deck.

Clearly defined limits in the SMS would have removed subjectivity from the decision making and established a common understanding for everyone involved in cargo handling operations.

Cargo handling operations on 14 July

Toolbox Talk

On July 14, Skandi Pacific’s master outlined the main points of the toolbox talk (TBT) for cargo operations to the persons involved in the cargo handling operations, that is, the IRs and 0000-0600 mates. The briefing outlined a number of pre-determined safety topics, including:

Type of operation, work equipment, methods/procedures to be adopted, communication, and human factor assessment, ‘Stop the Job’ policy, crane/lifting requirements, individual responsibilities for controls, access, manual handling, working environmental conditions, potential hazardous..., …‘good blocks stows’ and ‘lash cargo well.’

The weather conditions were also discussed and the master instructed the IRs and OOWs that if water was shipped on deck, then the work was to be stopped. All of them verbally acknowledged this instruction and then signed the TBT form. Further, before starting his duties, the IR on the 0200-0800 watch received a briefing from the chief mate and signed the TBT form to acknowledge he had been shown all the required provisions of the earlier TBT.

Water on deck

Between 0140 and 0502, seas were occasionally shipped on deck, increasing in regularity and size before 0500. Between 0502 and 0503, two large waves were shipped over the aft deck in quick succession, followed by another one at 0505 (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Seas washing across the aft deck at 0502 and 0505

Source: Skandi Pacific’s CCTV (annotations by ATSB)

Between 0507 and the time of the accident, after Skandi Pacific had stepped out from the rig, waves continued to be shipped on the aft deck from time to time. However, the IRs continued working, moving around the deck. At 0519, while they were at the aft end of the deck on the starboard side, a wave washed over the port side (Figure 12).

Figure 12: The CCTV frame at 0519

Source: Skandi Pacific’s CCTV (annotations by ATSB)

The design of the AHTS vessel with long, low aft decks without protective stern bulwarks meant that spray on deck and seas breaking over the stern were common. However, neither the mates nor the IRs on deck considered the water shipped on deck from 0502 onwards prevented the crew from lashing the cargo in those circumstances and conditions.

After the accident, the 0200-0800 IR who was also on deck stated that ‘at no time did he feel that we were working in unsafe weather conditions during any of the operations’. Hence, he did not consider stopping the job. This indicates that the definition of conditions when work was to be stopped, such as excessive water on deck, was subject to a person’s judgment and decision. The IRs statement suggests that there was a sense of security despite the worsening conditions.

Had the SMS contained clearly defined limits for excessive water on deck that necessitated stopping operations, the crewmembers would have been in a better position to make safe decisions. For example, the chief mate did stop backloading shortly after the DP status limit was exceeded. He had informed the rig that it was too rough with more water coming on deck making it dangerous for those operations and his crew. While the chief mate probably felt the need to ensure the cargo on deck was lashed, the risks to the men working on deck did not decrease by moving the vessel 30 m away from the rig. If anything, those risks increased as they moved around the deck lashing cargo in deteriorating weather conditions.

In submission to the draft investigation report, DOF management stated:

… There was no forewarning of the 2 unexpected waves, which occurred in close succession, and caused the incident.

However, between 0450 and the time of the accident, progressively larger waves were shipped on the vessel’s deck. The CCTV footage shows that during this period of about 33 minutes, at least 15 waves large enough to wash across the deck were shipped. When the vessel’s stern pitched into the wave coming over the stern, more water came on deck.

Backloading

From the commencement of cargo handling operations, six items were transferred to Atwood Osprey and nine items backloaded to Skandi Pacific. Figure 13 details the positions, relative sizes and types of cargo on deck after the cargo handling operations were suspended.

The shipboard CSM included guidance for crewmembers when backloading cargo:

- be aware that as soon as sea fastenings are released, there is a chance for the cargo to shift

- be aware of the potential of trapped hands between the tugger wire and cargo

- be aware that cargo can move when tightened by the tugger.

Securing mini-containers

It follows that if unsecured cargo can shift then safe practice is to minimise the amount of time the cargo is unsecured. The fact that cargo will be unsecured at times and be subject to external forces possibly leading to its movement should be identified through an appropriate RA.

In submission to the draft investigation report, DOF management stated:

Cargo is always unsecured for a period when backloading occurs. The Risk Assessment specifically dealt with the hazards posed by shifting cargo and stipulated additional control measures. The Toolbox Talk specifically provided for the cargo to be well lashed before departure.

However, the RA for loading deck cargo was completed before the cargo handling operations started. The identified hazard of shifting containers was to be mitigated by ‘Staying away from containers. Avoid enclosed areas’. After cargo handling operations were stopped at 0505, the RA was not reviewed nor were the risks associated with securing cargo in the prevailing conditions adequately assessed.

By about 0518, the IRs had hauled in the starboard tugger wire and tensioned the primary chain around the cargo. When checking the lashing, however, they found that forward two mini-containers were not secured and decided to use a secondary chain to secure them.

Figure 13: Stowage arrangement after cargo operations were stopped on 13 July

Source: Skandi Pacific’s master (annotated by ATSB)

Source: Skandi Pacific’s master (annotated by ATSB)

Their plan involved tensioning down the primary chain and securing a secondary chain to it. They decided to shackle the end of the secondary chain to the primary, to allow it to run along without snagging (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Utilising a secondary chain to secure cargo deck

Source: DOF management (annotations by ATSB)

Shortly afterwards, one of the IRs left the aft deck to get the shackle. Meanwhile, at the container, the other IR remained in the crush zone on the starboard forward end of the deck. He was in between the primary chain and the forward mini-container, inboard and outside of the crash barrier (Figure 9).

While the intent of the plan was to secure the cargo properly, the risks associated with the sequence of intended actions were not properly assessed. Importantly, the risk of working near unrestrained cargo that would be more susceptible to shifting as the weather conditions deteriorated, was not assessed. Furthermore, they did not comply with the master’s instruction to stop work if water was shipped on deck.

In submission to the draft investigation report, DOF management stated:

No prior assessment of the risk or any policy or safety procedure would have prevented the incident.

However, the need to secure cargo was a foreseeable risk. Securing the cargo needed to be undertaken after making conditions safe for the men to work on deck. At about 0520, the risk increased when the tugger wire was tensioned down, leaving containers 14, 10, 9 and 11 unrestrained. The risk further increased when the IR stepped into the crush zone forward of the cargo stow. At 0523, when the two large waves were shipped, the entire stow moved forward.

Essentially, the dangerous conditions while the IRs were securing the cargo were compounded when the primary chain was tensioned down and the IR stepped into a position from where he did not have a clear and unobstructed escape route.

Suspending cargo handling operations

Skandi Pacific was alongside the rig for about 4 hours on 14 July. The vessel’s station keeping status deteriorated to yellow several times, as it shifted more than 2 m from the set position.

At 0503, an alarm activated indicating the DP system status was red (that is, the vessel was more than 4 m from its set position). The chief mate stopped operations as required by the procedures and informed the rig. However, no one called the master to inform him of the suspended cargo handling operations nor discuss the current situation and changed activities on deck.

The chief mate moved Skandi Pacific, in DP mode, about 30 m away from the rig, stayed in the lee of Atwood Osprey, and maintained a heading of between 237° and 238°. The sea conditions continued to deteriorate and waves continued to be shipped over the vessel’s open stern.

The chief mate then instructed the IRs to secure the cargo with the vessel in this position. However, the risks of securing cargo with rough seas on the quarter and the vessel pitching heavily at times and shipping seas on deck were not adequately assessed or reviewed. Further, the master’s instruction to stop work if water was shipped on deck was not complied with.

Amongst the options the chief mate indicated he had considered were running with the weather until the cargo was secured or stepping out from the rig and staying in the lee until the cargo was secured. He had taken the latter option as in his opinion staying in the sheltered position off the rig was the safest option.

However, with rough seas on the quarter, the vessel pitching heavily at times and shipping seas on deck, it would have been prudent (and necessary) for the chief mate to call the master and discuss cargo securing options with him and the IRs. In other words, a review of the previous risk assessment or a reassessment. Calling the master would also have provided him the opportunity to reiterate or clarify his instruction that work be stopped if there was water on deck.

Had the chief mate called the master, other options to secure the cargo could have been considered. For example, in this situation the master indicated that he would have also considered running with the weather or tensioning the tugger wire around the cargo, then turning the vessel to protect the crewmembers on deck. As a result, the opportunity for the master to consider available options to prevent or reduce the likelihood of waves being shipped over the stern was lost.

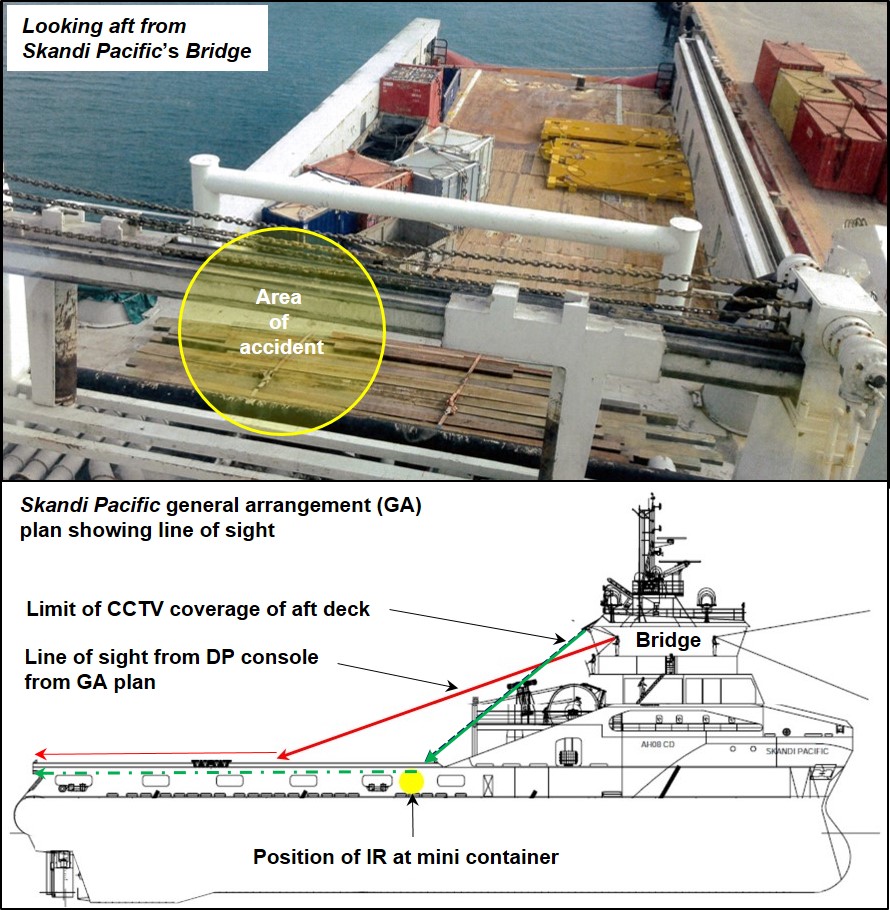

Supervision and communication

Skandi Pacific’s risk assessment for cargo transfer stated ‘Minimum of two competent persons to be on the bridge, one solely in charge of the DP, one monitoring communications and watching around the vessel for dangers. However, at about 0520 on 14 July, the chief mate, who was solely in charge of the DP system, was performing both tasks. At that time, the second mate on duty was in the forward part of the bridge entering the passage plan to Dampier into the electronic chart display and information system.

Communications between the bridge and the IRs on deck was maintained via UHF and VHF radio. At the time of the accident, the IR securing the secondary chain had the VHF radio for communications with the bridge and the rig’s crane. The IR who went to get the shackle had the UHF for direct communications with the bridge.

The risk assessment also required two men to be on deck when carrying out cargo operations. At interview, the master stated this was partly to ensure that no individual went into a crush zone without another watching for water coming over the stern and also to watch out for the other. However, this situation occurred shortly before 0523 when the IRs were separated as one IR went to the deck locker (located about 10 m forward) to get the shackle. It was during this short period of time (30 seconds) that seas broke over the stern and shifted the containers.

While the chief mate warned the deck crewmembers over the UHF radio ‘watch out, water on deck’, the IR working on the secondary chain did not have a UHF radio. In any case, even if he had heard the warning, he would have had little time to react.

Skandi Pacific’s procedures for cargo handling alongside installations included the following for backloading operations:

The OOW in charge of backloading should always have full sight of all cargo operations and personnel on deck including the crane wire and hook.

Figure 15: Line of sight of Skandi Pacific’s aft deck from the Bridge

Source: DOF Management (annotated by ATSB)

After the IRs had initially tensioned the tugger wire at about 0518, the chief mate observing from the DP console (Figure 15) on the bridge, believed that the cargo handling operations had been completed. After the accident, the chief mate stated ‘I thought they were almost finished as they were both out of sight and I could see the chains tightening’.

The aft deck had CCTV coverage and was visible on the monitors above the DP console. In this way it was possible to monitor the status of the work as far forward as the tugger winch including the area in which the IRs were working. However, the chief mate was the DPO and his responsibilities operating the DP system did not allow him to continuously monitor the CCTV screen. Furthermore, he was not aware of the IRs plans and intentions to secure the mini-containers as they did not inform the mates on the bridge.

In submission to the draft report, DOF management stated:

The IRs are not required to report that information to the mates. That was work which was performed by the IRs in the ordinary course of operations.

However, lashing cargo in the prevailing conditions with rough seas on the quarter with the vessel pitching heavily at times and shipping water on deck, was not the ‘ordinary course of operations’. Working in those high risk conditions was also contrary to the master’s instructions. The risks further increased when the IRs tensioned down the primary chain at about 0520 and then started rigging the secondary chain. At 0522, both men were working forward of the mini-container. Had one of them not left to get a shackle, the consequences of the accident could have been worse.

In any case, the purpose of the IRs carrying the two radios clearly was two-way communication to mitigate any risks by having a common understanding of the work/situation and for important messages, including warnings to be issued.

Exposed aft deck

Skandi Pacific’s aft deck had an open stern, which permitted seas to be shipped. The shipboard operating procedures for cargo handling alongside installations identified the exposed deck as follows:

Open stern anchor handling vessels require special care and consideration should be given to the open stern being physically barriered.

The procedures also stated the crewmembers and cargo were exposed to the elements when working with the stern towards the weather. The guidance stated that a RA and TBT were to be used to minimise their exposure to the weather.

However, Skandi Pacific’s managers had not adequately assessed the risks associated with working on the aft deck of vessels with open sterns, including the consideration of engineering controls to minimise shipping water on the vessel’s aft deck.

DP status

On 8 July, Skandi Pacific’s master submitted a management of change (MOC) form for a change of situation because number two bow thruster was out of service. This meant that the vessel no longer met DP class 2 status requirements.

The MOC form noted:

- Conditions of working alongside installation to be assessed by master and rig’s OIM prior to entry of 500 m zone and deemed acceptable.

- Manual manoeuvring if weather is acceptable but there is a force pushing on, however, resultant force must be drift off. No hose work in this instant.

- DP class 1[42] criteria for leeside working.

- RA to be done if hose work is intended stern should be into weather to reduce effect of loss of bow thruster.

The change in operational conditions necessitated a new or revised RA to be completed before work could be started.

The MOC was signed by the master, vessel manager and marine advisor. An additional RA was then undertaken, for working on an installation with DP class 1 status, when on the lee side of the rig. The activities assessed were setting up DP, DP work on lee side and deck cargo handling operations.

The risk level was assessed as ‘medium’[43] which required additional control measures be implemented to reduce the residual risk level to ‘low’.[44]

The measures put in place following the failure of the bow thruster were appropriate in the prevailing circumstances. Skandi Pacific was manoeuvred into position off the oil rig, stern in, on a heading of between 237° and 238°, similar to the previous OSV. The vessel maintained position on station at the rig until 0505, when operations were stopped by the chief mate.

__________

- Bulk cargo operations involves the transfer of potentially hazardous liquids by use of hoses between vessel and rig.

- The average of the highest one-third of a set of measured waves. The maximum wave height can be up to twice the significant wave height.

- DP equipment class 1 has no redundancy. Loss of position may occur in the event of a single fault.

- Task should only proceed with appropriate management authorisation after consultation with special personnel and assessment team. Where possible the task should be redefined to take account of the hazards involved or the risk should be recorded further prior to task commencement.

- The task may be acceptable, however, it should be reviewed to determine if the risk can be reduced further.

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the crewmember fatality on board Skandi Pacific, at sea on 14 July, 2015. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

Safety issues, or system problems, are highlighted in bold to emphasise their importance. A safety issue is an event or condition that increases safety risk and (a) can reasonably be regarded as having the potential to adversely affect the safety of future operations, and (b) is a characteristic of an organisation or a system, rather than a characteristic of a specific individual, or characteristic of an operating environment at a specific point in time.

Contributing factors

- Skandi Pacific’s officer of the watch suspended cargo handling operations due to adverse weather conditions, including water on deck, and moved the vessel off the oil rig to secure cargo on its aft deck.

- The task of securing the cargo after operations were stopped and the options to safely complete it were not adequately assessed.

- The vessel remained on the same heading in dynamic positioning (DP) mode because the officer of the watch considered this the safest option instead of others, such as running with the weather.

- The master was not called and remained unaware of the situation and, hence, did not get the opportunity to consider safer options for securing cargo, such as running with the weather or changing the vessel’s heading.

- Working on deck when water was being shipped was contrary to the master’s instructions.

- In an attempt to secure cargo effectively, the vessel’s crewmembers tensioned down the primary securing chain, which left the entire block of cargo unsecured.

- The crewmembers on deck carried out their plans in isolation without the active involvement of the officers on watch.

- A crewmember was standing in a position of danger when attempting to fasten a securing chain forward of a block of cargo.

- A large wave came over the vessel’s stern and shifted the block of cargo, which crushed the crewmember, fatally injuring him.

- While it was required to have two men on the working deck, at the time of the accident, the men on deck were separated for about 30 seconds, after one of them went forward to the deck locker to get a shackle to resecure the cargo.

- Skandi Pacific’s safety management system (SMS) procedures for cargo handling in adverse weather conditions were inadequate.Clearly defined weather limits when cargo handling operations could be undertaken and trigger points for suspending operations were not defined, including limits for excessive water on deck. [Safety issue]

- Skandi Pacific’s SMS procedures for cargo securing were inadequate. There was no guidance for methods of securing cargo in adverse weather conditions. [Safety issue]

Other factors that increased risk

- Skandi Pacific’s managers had not adequately assessed the risks associated with working on the aft deck of vessels with open sterns, including consideration of engineering controls to minimise water being shipped on the aft deck. [Safety issue]

- At the time of the accident, the officer who was solely in charge of the DP system was performing the tasks of both the DP officer and the communications/monitoring officer, contrary to the risk assessment for cargo transfers. The other officer on the bridge was occupied entering the vessel’s next passage plan into the electronic chart display and information system.

- During the operations leading up to the accident, the officers on the bridge did not keep the men on the aft deck in sight at all times as required by the vessel’s cargo handling procedures. Further, the radio communication between the men on deck and the officers was inadequate.

Other findings

- While one of Skandi Pacific’s bow thrusters was not operational at the time of the accident, the ‘management of change’ (MoC) process implemented as a result of its failure was appropriate. The vessel was capable of conducting operations within the limitations/conditions defined by the MoC process, and did so while on station at and off the rig.

The safety issues identified during this investigation are listed in the Findings and Safety issues and actions sections of this report. The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) expects that all safety issues identified by the investigation should be addressed by the relevant organisation(s). In addressing those issues, the ATSB prefers to encourage relevant organisation(s) to proactively initiate safety action, rather than to issue formal safety recommendations or safety advisory notices.

All of the directly involved parties were provided with a draft report and invited to provide submissions. As part of that process, each organisation was asked to communicate what safety actions, if any, they had carried out or were planning to carry out in relation to each safety issue relevant to their organisation.

Where relevant, safety issues and actions will be updated on the ATSB website as information comes to hand. The initial public version of these safety issues and actions are in PDF on the ATSB website.

Cargo handling procedures

| Number: | MO-2015-005-SI-01 |

| Issue owner: | DOF Management, Norway (DOF Management) |

| Operation affected: | Marine: Shipboard operations |

| Who it affects: | All owners and operators of offshore support vessels |

Safety issue description:

Skandi Pacific’s safety management system (SMS) procedures for cargo handling in adverse weather conditions were inadequate. Clearly defined weather limits when cargo handling operations could be undertaken and trigger points for suspending operations were not defined, including limits for excessive water on deck.

Proactive safety action taken by DOF Management

Action number: MO-2015-005-NSA-003

Following the accident, DOF management submitted a ‘safety flash’ to the offshore industry organisation, International Marine Contractors Association. The safety flash summarised key safety matters and the accident, allowing wider dissemination of lessons learned to the industry. The company also undertook to review the adverse weather working guideline and the cargo loading procedure to include cargo lashing arrangements, and risk assessment for securing cargo.

Subsequently, DOF Management advised the ATSB that the existing working in adverse weather procedure had been reviewed and updated. The procedure now includes weather limits related to specific wind speeds, sea state, tidal streams, visibility and vessel movement. The precautions to be taken are directly related to each of the trigger points. In addition, working parameters for vessels with open sterns include a trigger point in the event that water is shipped on deck over the stern. The master is to be informed, who is then required to have a risk assessment conducted.

Current status of the safety issue

Issue status: Adequately addressed

Justification: The revised procedures for working in adverse weather and cargo handling, and the additional safety action taken has adequately addressed the safety issue.

Cargo securing procedures

| Number: | MO-2015-005-SI-02 |

| Issue owner: | DOF Management, Norway |

| Operation affected: | Marine: Shipboard operations |

| Who it affects: | All owners and operators of offshore support vessels |

Safety issue description:

Skandi Pacific’s safety management system (SMS) procedures for cargo securing were inadequate. There was no guidance for methods of securing cargo in adverse weather conditions.

Proactive safety action taken by DOF Management

Action number: MO-2015-005-NSA-002

Following the accident, DOF management submitted a ‘safety flash’ to the offshore industry organisation, International Marine Contractors Association. The safety flash summarised key safety matters and the accident, allowing wider dissemination of lessons learned to the industry. The company also undertook to review and update the cargo securing procedure and risk assessment to include the requirement for a lashing plan and load sequence planning with rig prior to entry of 500 m zone.

Subsequently, DOF Management advised the ATSB that its existing cargo loading procedure and risk assessment had been revised to include further clarification surrounding cargo lashing and hazards of shifting cargo. The revised procedure contains trigger points for assessing further operation when there is:

- water on deck over the stern

- an unexpected deterioration in weather

- an unfavourable change of the vessel position/heading.

Additionally, when offloading and backloading cargo alongside offshore installations, the risk assessment for securing cargo is to be reviewed and updated to ensure all hazards of shifting cargo are identified and addressed.

Further, a simultaneous operations (SIMOPS) procedure for combined rig and vessel cargo loading operations has been developed and implemented. The SIMOPS procedure is in addition to the procedures for working in adverse weather and cargo loading.

Current status of the safety issue

Issue status: Adequately addressed

Justification: The revised procedures and risk assessments for cargo handling and securing, and the additional safety action taken has adequately addressed the safety issue.

Open stern offshore support vessels

| Number: | MO-2015-005-SI-03 |

| Issue owner: | DOF Management, Norway |

| Operation affected: | Marine: Shipboard operations |

| Who it affects: | All owners and operators of offshore support vessels |

Safety issue description:

Skandi Pacific’s managers had not adequately assessed the risks associated with working on the aft deck of vessels with open sterns, including consideration of engineering controls to minimise water being shipped on the aft deck.

Response to safety issue by DOF Management

Action number: MO-2015-005-NSA-004

Following the accident, DOF management submitted a ‘safety flash’ to the offshore industry organisation, International Marine Contractors Association. The safety flash summarised key safety matters and the accident, allowing wider dissemination of lessons learned to the industry. The company also undertook to conduct of a risk assessment for anchor handling tug supply (AHTS) vessels conducting cargo operations. The risk assessment was to include considering engineering controls to minimise excessive water on the vessel back deck (for example, stern door or other vessel type).

Subsequently, DOF Management advised the ATSB that the existing risk assessment for offloading deck cargo at installation had been reviewed and updated to include a section regarding risks associated with securing cargo. The company indicated that it had assessed and mitigated risks associated with vessels with open stern.

ATSB comment/action in response

The ATSB acknowledges the proactive safety taken by DOF Management. However, the ATSB considers further action is necessary to adequately address the risks associated with the use of vessels with open sterns, including the engineering controls to minimise shipping seas on the aft deck proposed in the company’s response. Therefore, the ATSB has issued the following recommendation and safety advisory notice.

ATSB safety recommendation to DOF Management

Action number: MO-2015-005-SR-006

Action status: Released

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau recommends that DOF Management take further action to adequately address the safety issue concerning the use of vessels with open sterns.

Current status of the safety issue

Issue status: Partially addressed

Justification: Further action by DOF Management to adequately address the safety issue, including the company’s proposal to consider engineering controls to minimise shipping seas on the aft deck of open stern vessels, is considered necessary.

ATSB safety advisory notice to masters, owners and operators of offshore support vessels

Action number: MO-2015-005-SAN-005

Action status: Closed

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau advises the masters, owners and operators of all offshore support vessels to ensure that the risks associated with working on the aft deck of vessels with open sterns are adequately assessed.

Additional safety action

Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence.

DOF management advised the ATSB that a marine risk awareness presentation titled SAFE the RITE WAY and a safety handbook have been developed and implemented. A 'lessons learned' communication plan from this accident are included in the SAFE the RIGHT WAY induction and presentation. Presentations have been delivered both externally to industry partners and forums and internally via mandatory DOF induction training.

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- Skandi Pacific’s master and directly involved crewmembers

- DOF Management

- Geoscience Australia

- National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (NOPSEMA)

- Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA).

References

International Maritime Organisation, 2015, The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) 1974, as amended, IMO, London.

International Maritime Organisation Resolution A.489(XII), Adopted on 19 November 1981, Safe Stowage And Securing Of Cargo Units And Other Entities In Ships Other Than Cellular Container Ships Cargo Securing Manual.

International Maritime Organisation Resolution A.863(20), Code of Safe Practice for the Carriage of Cargoes and Persons by Offshore Support Vessels (OSV Code), as Amended.

Guidelines for Offshore Marine Operations (G-OMO), Guidelines for Offshore Marine Operations Revision: 0611-1401, 2013. Visit www.g-omo.info and follow the link on the G-OMO tab to Guidelines for Offshore Marine Operations.

National Offshore Petroleum Titles Administrator (NOPTA), Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006. Visit www.nopta.gov.au and follow the link on the Legislation, determinations, guidelines & fact sheets tab to offshore petroleum acts.

Ritchie, G 2008, Offshore Support Vessels, A Practical Guide, The Nautical Institute, UK. Visit www.nautinst.org and follow the link on the Publications to the publications list.

Submissions

Under Part 4, Division 2 (Investigation Reports), Section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 (the Act), the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. Section 26 (1) (a) of the Act allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the Australian Maritime Safety Authority, The Bahamas Maritime Authority, DOF Management, National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority and the master, chief mate, second mates and integrated ratings on board Skandi Pacific and the integrated rating’s next of kin.

Submissions were received from the Australian Maritime Safety Authority, The Bahamas Maritime Authority, DOF Management, National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority and the master on board Skandi Pacific and the integrated rating’s next of kin. The submissions were reviewed and where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2016