What happened

On 2 October 2015, the pilot of a Cessna 182 aircraft, registered VH-DNZ (DNZ), was tasked to conduct parachute operations. The pilots of two aircraft, the Cessna 182 along with a Cessna 206 (C206), planned to depart from Parafield Airport, and drop parachutists to land at Victoria Park, Adelaide, before returning to land at Parafield, South Australia. A total of four similar ‘sorties’ were planned for the day.

The target landing zone for the parachutists was Victoria Park, which would require the pilots to obtain a clearance from Adelaide air traffic control (ATC) to enter Adelaide control zone. Parachute operations normally included a drop area of a 1 NM radius around the target landing zone. However, the north-western corner of that 1 NM radius circle from Victoria Park infringed on the separation required for aircraft arriving and departing on runway 05/23 at Adelaide Airport. Therefore, the drop area agreed between Airservices Australia and the Australian Parachute Federation (APF) for the operation was as depicted by the red zone in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Drop area agreed between Australian Parachute Federation and Airservices Australia

Source: Australian Parachute Federation – annotated by ATSB

On the day, the wind was from the northwest, which required the parachute aircraft to run in to the northwest, in order to drop the parachutists upwind of the target zone. Operating to the northwest of the agreed red zone, and thus outside the previously agreed parameters of the red zone, would place the parachute aircraft in the main runway separation zone at Adelaide, with the possibility of associated delays in ATC providing a clearance.

The pilots of the two aircraft arrived at Parafield at about 0930 Central Daylight-saving Time (CDT) and discussed the details for the day’s operations. These details included the direction of the jump run, ATC clearances, two ‘staging areas’ – one north and one south of the drop zone at Victoria Park, where the aircraft could hold if required, and different inbound and outbound flightpaths to assist in ensuring separation between the two aircraft.

At about 1030, the pilot of DNZ conducted a daily inspection of the aircraft, and did not find any defects. The pilot added fuel to bring the total to 110 L of fuel on board the aircraft. The pilot assessed that was more than adequate for the proposed 28-minute sortie (see Fuel calculations for further information).

After preparing the aircraft, the two pilots spoke to the nominated contact person from Adelaide ATC and the APF ground personnel at Victoria Park to coordinate the day’s plans.

At about 1220, the parachutists arrived at Parafield Airport. After the parachutists boarded the aircraft, the C206 was to depart first, followed about 10 minutes later by DNZ. The pilot of DNZ observed the C206 engine start, and then shut down again almost immediately. The reason for the engine shut down was that ATC had advised the C206 pilot that, due to aircraft arriving at Adelaide, if they departed now, there would be a 20-minute delay. ATC also advised that if the aircraft took off at 1320, they would not have to wait. The C206 subsequently departed at about 1320.

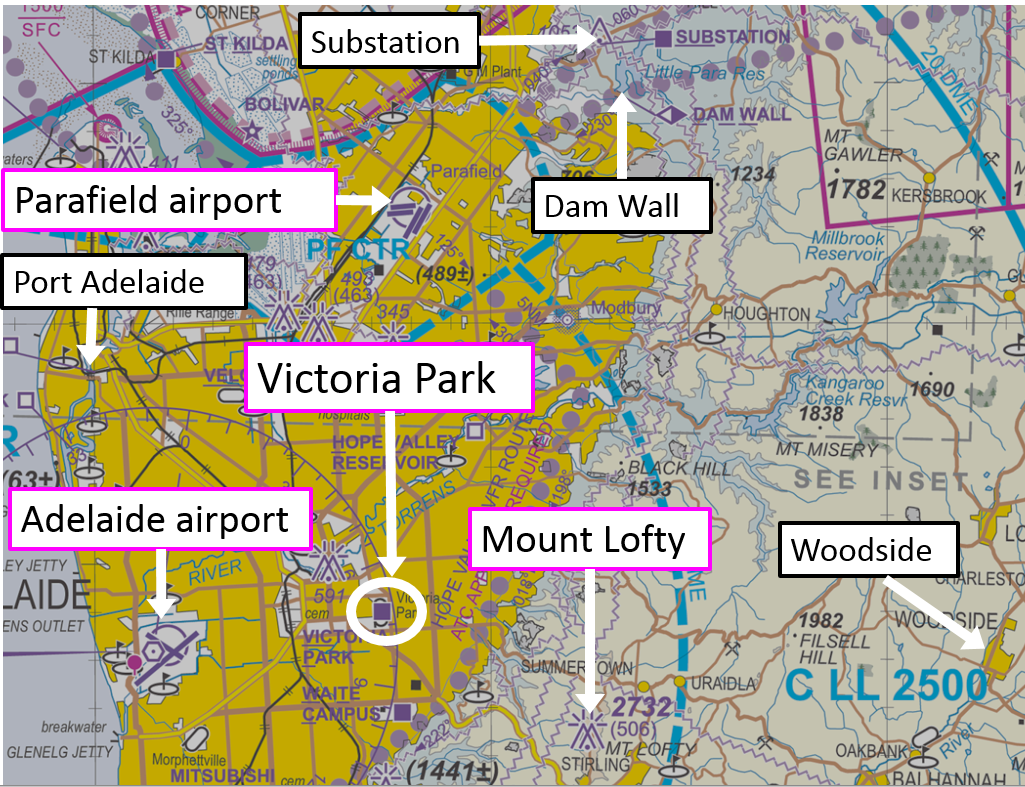

At about 1327, the pilot of DNZ started the aircraft’s engine, and DNZ departed from Parafield at 1331, with the pilot and four parachutists on board. The aircraft tracked outside controlled airspace, overhead Substation, then towards Woodside (Figure 2). At about 1337, when about 2 NM north of Woodside, at 2,500 ft, the pilot of DNZ contacted Adelaide Approach air traffic control, and requested an airways clearance to enter controlled airspace to complete the parachute drop. The approach controller advised the pilot of DNZ to remain outside Class C airspace.

At about 1340, the approach controller cleared the pilot of DNZ to track from their current position to Woodside then to Staging Area South and climb to 3,500 ft. The Staging Area South was overhead Mt Lofty. The C206 was already holding in Staging Area South at 4,500 ft. The pilot of DNZ communicated with the C206 pilot on the company radio frequency, sighted that aircraft, and maintained visual contact with it.

At about 1355, the approach controller cleared the pilot of the C206 to track for the drop point and, about 2 minutes later, cleared the pilot to conduct the drop. After completing the drop, the C206 was cleared to the northern staging area, then to return to Parafield.

The pilot of DNZ continued to hold at Mt Lofty, at 3,500 ft, conducting orbits of 3-4 minutes duration each.

Figure 2: Adelaide visual terminal chart with relevant locations

Source: Airservices Australia annotated by the ATSB

At about 1406, after completing seven orbits, the pilot of DNZ was advised to expect about a 30-minute delay, with a drop time of 1445. The pilot calculated the approximate fuel remaining, and assessed that they would be approaching the minimum fuel required to return safely to Parafield. The pilot contacted the APF ground personnel at Victoria Park to advise them of the requirement for further holding. They responded that they would phone the ATC representative and then let the pilot know what they would like them to do.

About 2 minutes later, the approach controller revised the estimated drop time to 1433. At about 1411, the pilot of DNZ asked the approach controller whether an earlier clearance would be available if they amended the run into the original red zone (Figure 1). Remaining within the red zone would increase the distance of DNZ from aircraft on final approach to runway 23 at Adelaide, and potentially expedite a clearance. The controller replied that if they could remain in the original area, they could expect a drop time of 1426. The controller confirmed again at 1417 that they had reports the wind was suitable (to operate within the red zone), so the pilot of DNZ could expect a clearance only into the original red zone.

At about 1420, the approach controller asked the pilot of DNZ to confirm they were maintaining 3,500 ft. At that time, the engine ran roughly, and the aircraft momentarily descended. The pilot conducted emergency checks; changing the selected fuel tank from right to both and then left, assessing the full range of throttle and rpm, and switching between the magnetos, but the engine continued to run roughly. The engine temperature and pressure gauges were indicating in the normal range. The pilot decided to abandon the parachute drop and requested a clearance to track directly from their current position to Parafield, due to fuel. About 1 minute later, the approach controller asked the pilot of DNZ whether they could accept a clearance to track to Port Adelaide, over other traffic that was on final approach to runway 23 at Adelaide, and the pilot replied ‘affirm’. At about 1422, the controller cleared the pilot of DNZ to track to Port Adelaide at 3,500 ft.

The rough running then got worse, so at about 1424, the pilot requested a landing at Adelaide Airport although did not, at that stage, declare an emergency. The approach controller advised the pilot to expect a clearance to land at Adelaide, and advised that traffic was a Conquest at 5 miles, landing on runway 23, and to report sighting that aircraft. The pilot replied ‘not sighted, where again sorry?’ and the approach controller replied ‘your 12 o’clock[1], 4 miles on final for runway 23’.

The pilot continued to attempt to resolve the engine issues, and communicated with the ground personnel to advise of the situation. The pilot reported also looking for a suitable landing site in case the engine stopped completely and a forced landing was required. At about 1425, the approach controller cleared the pilot of DNZ to descend to 2,000 ft. Twenty-six seconds later, the approach controller cleared the pilot of DNZ for a visual approach to left base for runway 23.

Just then, the engine stopped completely. The pilot had sighted Victoria Park racecourse out to the right side of the aircraft, so turned immediately towards it. At about 1426, the pilot made a MAYDAY[2] call to Adelaide Approach, advising that they were conducting a forced landing at Victoria Park. The pilot secured the aircraft engine, and told the parachutists to bring their weight forwards and to brace for impact.

The pilot aimed to land the aircraft in ‘pit straight’ on the racecourse, which was directly into the north-westerly wind, but as the aircraft lined up with the straight, the pilot saw a car on the bitumen. The pilot conducted a turn to the right then to the left and landed the aircraft on grass. The pilot reported that it was a very heavy landing, and that the aircraft landed either flat or nose wheel first. The nose wheel broke off, the propeller struck the ground, and the aircraft slewed to the left. Two of the parachutists were ejected from the aircraft during the impact. Two of the parachutists sustained serious injuries, and two were uninjured. The pilot sustained minor injuries and the aircraft was substantially damaged (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Accident site showing damage to VH-DNZ

Source: South Australia Police

Fuel calculations

During the pre-flight inspection, the pilot dipped the fuel tanks to determine the amount of fuel in the tanks. The dipstick indicated that about 80 L of fuel remained in the aircraft’s right fuel tank and zero in the left fuel tank. The pilot reported that this correlated with the fuel log from the previous day’s flight along with the aircraft being parked on a slope leaning slightly to the right. The pilot added 30 L of fuel to the left tank, so there was a total of 110 L of fuel on board the aircraft. Based on a planned fuel consumption rate of 65 L/hr for parachute operations, the pilot calculated that there was sufficient fuel for 1.7 hours of flight. The pilot assessed that was more than adequate for the planned 28-minute sortie.

The engine started surging about 50 minutes after the aircraft departed from Parafield, and stopped completely about 5 minutes later.

The planned fuel consumption rate of 65 L/hr was used for parachute operations. The actual fuel consumption recorded for the aircraft in cruise flight was less, due to operating at a reduced power setting and a leaner fuel/air mixture. The aircraft handbook stated the cruise performance with the mixture leaned at 5,000 ft above mean sea level (AMSL) and 2,000 rpm and 20 inches manifold pressure, was about 32 L/hr. The pilot reported that about 10-11 L of fuel in each tank was unusable.

Phone communications between APF and ATC

At about 1100, the ground representative from the APF rang the nominee from ATC, and advised that due to wind of 25 kt from 310°, they would need to extend the boundaries from the original ‘red zone’, to about 1 NM north-west of the target landing site. The APF representative also stated that they were aware that the extended area would incur delays due to jet aircraft operating into Adelaide Airport.

The APF representative advised ATC that the pilots had fuelled up so they could hold.

When the pilot of DNZ was advised of a 30-minute hold, the ground representative from the APF rang ATC, and asked whether they could operate in accordance with the red zone (rather than the extended zone), as the wind was not as strong as forecast. The ATC nominee advised that they would be able to get a clearance for that in about 15 minutes and the APF representative advised that the pilot would have sufficient fuel for that.

Pilot comments

The pilot of DNZ provided the following comments:

- The pilot reported that after start-up, the fuel gauge indications corresponded with having 80 L and 30 L of fuel in the tanks. The pilot did not look at the fuel gauges again at any stage of the flight, or include the fuel gauges in the instrument scan while performing emergency checks.

- During the emergency procedures, changing the fuel tank selector from Right to Both and to Left did not make the rough running of the engine any better or worse.

- The pilot did not apply carburettor heat at any time.[3]

- The pilot requested a clearance to track direct to Parafield rather than tracking outside controlled airspace to the east, because there were no suitable places to conduct a forced landing due to steep, hilly terrain.

- During the flight, the pilot had kept a mental fuel log based on time in the air and estimated fuel remaining, but not a written log.

- While holding over Mt Lofty, the pilot had the engine set at about 20 inches manifold pressure and 2,100-2,200 rpm, and estimated holding for about 40-45 minutes at that power setting. The pilot had leaned the fuel mixture to slightly rich of peak exhaust gas temperature.

- The planned duration of the sortie, from Parafield to drop the parachutists and return, was 28 minutes, so the pilot expected that with holding that might increase to about 45 minutes.

- The pilot was not aware that the APF ground personnel advised ATC that the pilots were able to accept significant delays.

- The pilot heard a commotion with the parachutists in the back, and after the incident, realised that the parachutists had been asking to exit the aircraft.

Parachutist comments

One of the parachutists, who was also a licenced pilot and owner of Cessna 182 aircraft, provided the following comments:

- The communications prior to commencing the flight were poor. The parachutists were advised they would be dropped from 6,000 ft, which was not their preferred height for the operation.

- There was little to no communication with the pilot prior to departure, including no safety briefing to the parachutists. A safety briefing card or placard in the aircraft, detailing emergency procedures, may assist in an emergency.

- As the aircraft became airborne, the parachutist, who had been struggling to fasten the single point harness, realised that it was unserviceable. This resulted in parachutists being ejected from the aircraft during the collision.

- When holding around Mt Lofty, the parachutist was concerned that the pilot had an unusually high power setting for holding. That may have significantly increased the fuel consumption. The sound of the high power setting did not change until the engine coughed and spluttered a few minutes before it stopped.

- As soon as they heard the engine issues, the parachutists asked the pilot if they could jump, as they had sighted suitable safe landing areas below. The pilot reportedly rejected their request. They made a further request to jump when approaching 1,500 ft above ground level, as their lowest safe exit height, but again the pilot refused the request.

- The pilot extended flap and then retracted it late in the approach, which resulted in a very high rate of descent. The aircraft’s left wingtip came into very close proximity with a building at that time.

Australian Parachute Federation report

A representative of the Australian Parachute Federation aircraft committee inspected the aircraft following the accident. The representative found that the aircraft impacted the ground very heavily in a nose-down attitude. About half a litre of fuel was drained from the system after the aircraft was removed from the site.

The report stated that the aircraft should still have had fuel on board, based on taking off with 110 L on board, and at the maximum consumption rate. However, while holding and conducting continuous right orbs, fuel may have been lost from the tanks due to venting from the fuel valve.

Video footage

The ATSB obtained video footage of the incident taken from inside the aircraft. During the approach, the aircraft banked steeply to the right towards a built-up area, then to the left towards the landing site. As the aircraft wings levelled, the nose pitched up and the left wing appeared to come into close proximity with a building. At that time, the pilot retracted the flaps. The aircraft then descended rapidly and collided with the ground in a nose-down attitude.

CASA investigation

The Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) also conducted an investigation into the incident. At the time of publication of the ATSB report, CASA had not finalised its investigation. CASA advised the ATSB that two fuel dipsticks appear to have been in use by the aircraft operator. One dipstick had fuel quantity depicted in 10 L increments, the other in 20 L increments. If the pilot had calculated the fuel on board based on 20 L increments, but used a dipstick with 10 L increments, rather than having 110 L of fuel on board at start-up, there would have been 55 L. That fuel quantity correlated with the length of time the engine ran before fuel exhaustion occurred. Additionally, the same aircraft had been involved in a similar fuel starvation incident in 2011, where the CASA investigation found that there was probably more than one dipstick in use at the time.

CASA subsequently provided the ATSB with its final investigation report into the accident. CASA’s investigation did not locate any dipstick for the aircraft and concluded that the engine failure was most likely due to ‘fuel exhaustion as a result of the incorrect calculation of the available fuel in DNZ’s tanks prior to the accident flight.’

Safety message

Pilots are reminded of the importance of careful attention to aircraft fuel state. ATSB Research report AR-2011-112 Avoidable accidents No. 5 Starved and exhausted: Fuel management aviation accidents, discusses issues surrounding fuel management and provides some insight into fuel related aviation accidents. The report includes the following comment:

Accurate fuel management also relies on a method of knowing how much fuel is being consumed. Many variables can influence the fuel flow, such as changed power settings, the use of non-standard fuel leaning techniques, or flying at different cruise levels to those planned. If they are not considered and appropriately managed then the pilot’s awareness of the remaining usable fuel may be diminished.

This incident also highlights that a timely decision to conduct a precautionary landing may be better than having no choice but to conduct a forced landing.

Aviation Short Investigations Bulletin - Issue 48

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2016

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________

- The clock code is used to denote the direction of an aircraft or surface feature relative to the current heading of the observer’s aircraft, expressed in terms of position on an analogue clock face. Twelve o’clock is ahead while an aircraft observed abeam to the left would be said to be at 9 o’clock.

- Mayday is an internationally recognised radio call for urgent assistance.

- The Bureau of Meteorology provided the ATSB with a report of the weather conditions at the time of the incident, including temperature, dew point and relative humidity. There was no risk of carburettor icing.