What happened

On the afternoon of 28 June 2014, the 327 m long bulk carrier Julia N entered the port of Port Headland, Western Australia, and was manoeuvred alongside Anderson Point number two berth by the pilot with the assistance of four tugs.

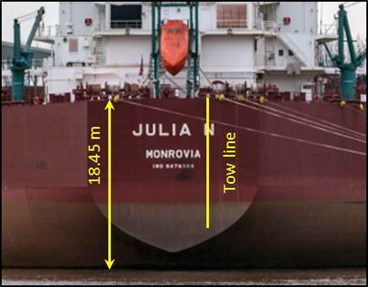

At 1521[1], when it had been confirmed that the ship was in position, the pilot called the master of the tug at the stern of the ship to come in and retrieve its tow line (Figure 1 and Figure 2). When the tug was in position, the pilot asked Julia N’s master to instruct the aft mooring team (second mate and two seamen) to let go the tug’s tow line.

Figure 1: Approximate position of the tow line during retrieval[2]

Source: Jens Boldt – Shipspotting with annotations by ATSB.

Figure 2: View of Julia N from the tug’s bridge window

Source: Teekay Australia.

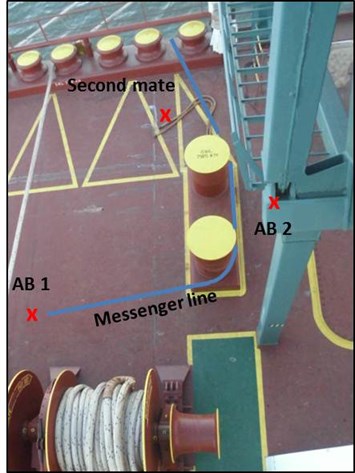

Figure 3: Crew and messenger line positions

Source: Julia N with annotations by ATSB

Seaman 1 (Figure 3) ran the messenger line[3] over the drum end of the mooring winch, while seaman 2 operated the winch to pull about 2 m of tow line inboard. The second mate wrapped the rope stopper around the main tow line while the messenger line was taken off the drum end and the eye of the tow line off the mooring bits. The messenger line was then put around the forward post of the mooring bits to assist with the controlled lowering of the tow line.

On board the tug, the general purpose hand was standing forward of the winch (Figure 4) ready to guide the tow line onto the winch drum and the engineer was at the remote winch controls inside the bridge.

The general purpose hand signalled to the engineer that he could begin heaving in the tow line but the engineer waited until he saw the tow line being lowered.

Figure 4: Position of the general purpose hand and the engineer.

Source: ATSB.

As the tow line was retrieved, seaman 2’s right leg somehow became entangled in the messenger line. He was then dragged about 4 m across the deck and into the rollers of the fairlead. When his legs entered the fairlead the messenger line came under tension and it severed the seaman’s right foot.

As the eye splice of the tow line reached the fendering on the bow of the tug, both the general purpose hand and the engineer saw the line go tight. The general purpose hand signalled to the engineer but he had already stopped heaving.

Julia N’s second mate ran to the ship’s rail and signalled to the general purpose hand to slacken the line. Then, on the general purpose hand’s signal, the engineer paid out about 2 m of line.

At 1524, the pilot advised Port Hedland Vessel Traffic Service (VTS) that there was a medical problem on board the ship and instructed the tug’s master to hold position with a slack line as there had been a problem on the aft mooring deck with the line. A short time later, after receiving more information, the pilot advised VTS what had happened. He also requested medical assistance from the terminal operator.

Between 1545 and 1555, two launches arrived with first aid personnel and, at 1601, a helicopter with two paramedics landed on board Julia N.

At 1644, the helicopter departed with the injured seaman. He was taken to the Port Hedland Hospital, where he was provided with medical treatment.

At 1750, the pilot reported to VTS that Julia N was all fast alongside the berth and he was departing the ship.

The injured seaman continued to receive treatment in the Port Hedland Hospital until he was repatriated on 12 July.

ATSB comment

From his position at the port bridge console, the tug’s engineer could see the tow line, the winch and the general purpose hand. However, due to the freeboard of the ship, no one on board the tug could see past the ship’s main deck hand rails. As is usual, the tug’s crew had no direct radio communications with the ship’s aft mooring team, and were therefore reliant on visual contact with the mooring team for all communications.

There were three crew members (second mate and two seamen) on the aft deck for mooring operations and it is likely that the second mate felt that he needed to assist the two seamen when releasing the tugs line from the bits. However, when doing so, he was not at the ship’s side where he had a clear line of sight of the tug, and as such had relinquished his supervisory role. Then, when the seaman became entangled in the messenger line, there was no one on the aft deck of the ship in a position to signal to the tug’s crew to stop retrieving the line.

The investigation was not able to interview the injured seaman, and from the evidence provided, was not able to ascertain how the seaman’s leg became entangled in the messenger line while it was being retrieved on board the tug.

There is no clear evidence to determine the actions of the second mate and how they were interpreted by the tug’s crew as a positive signal to retrieve the tow line.

Safety action

Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following safety action in response to this occurrence.

Teekay Australia

A Safety Alert was sent to all of its managed ships advising of the accident, the safety message and safety actions to be taken.

Neu Seeschiffahrt

Each managed ship received a Corrective and Preventative Action Report which contained the company’s internal investigation report, references to various procedures related to mooring and tug operations as well as corrective actions and long term preventative actions.

Safety message

Mooring operations are often seen as a routine task but contain dangers that are often not realised until it is too late. As they cannot be directly observed, the forces that can be exerted on mooring and towing lines, even by their own weight, are often underestimated by those working around them.

Serious injury is likely when there is an incident during tug and mooring operations, but the likelihood of such an occurrence can be managed through effective risk assessment, training, supervision, communications and good housekeeping – both prior to and during berthing operations.

The ATSB’s SafetyWatch highlights the broad safety concerns that come from its investigation findings, and from the occurrence data reported by industry. One of the ATSB’s current SafetyWatch concerns relates to marine work practices. Readers are encouraged to examine the information and experiences presented at the web link below, and relate those to the context of their own duties.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2014

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] All times referred to in this report are local time, Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) + 8 hours.

[2] Photo is for illustrative purposes. At the time of the incident, Julia N’s draft was less than shown in the photograph.

[3] The messenger line was a 25 mm diameter rope attached to the eye of the main tow line by a short flat webbing sling. It was measured at 21.7 m long after the incident.