What happened

At 1503 Eastern Standard Time on 27 May 2014, mutual traffic information was not passed to the flight crews of a Department of Defence (Defence) Boeing CH‑47 Chinook helicopter (CH‑47), and a Cessna 172S, registered VH‑PFU (PFU), operating in the circuit area at Townsville Airport, Queensland. At the time, the Defence air traffic controller with jurisdiction over the circuit area (the tower controller), had six other aircraft on frequency. All of the aircraft were operating under visual flight rules in visual meteorological conditions.

The complexity of aircraft operations, and a high level of radio frequency use, resulted in high workload for the tower controller and the tower supervisor.

The flight crew of the CH‑47 had been issued with a clearance limit of a point on the coast north‑east of the airport. At the same time, the flight crew of PFU were tracking on the centreline of runway 07 as instructed by the tower controller. As the flight crew of the CH‑47 turned left to commence an orbit at the clearance limit, they sighted PFU in close proximity. The flight crew reversed the turn, tracking away from PFU.

Seeing that the CH‑47 had commenced a turn away from the track of PFU, the tower controller did not provide traffic on PFU, but instead provided traffic on another aircraft that the CH‑47 was to track behind. Additionally, traffic on the CH‑47 was not passed to the flight crew of PFU. When the flight crew of the CH‑47 first reported sighting PFU, surveillance data indicated that the aircraft were at the same altitude and separated by about 0.5 NM (1 km).

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that mutual traffic information was not passed to the flight crews of the CH‑47 and PFU prior to them coming into proximity. Then, when the flight crew of the CH‑47 reported PFU in sight, the tower controller did not pass traffic on that aircraft as they believed that the proximity risk had been resolved by the CH‑47 turning away. At the time of the occurrence, compromised separation recovery training deficiencies existed within Defence.

What's been done as a result

Actions by Defence in relation to compromised separation recovery training have adequately addressed the identified training deficiencies. In addition, Defence has reinforced to controllers, via briefings, the importance of workload and traffic management.

Safety message

The impact of workload can be insidious, the affected person(s) not realising an increase until it has reached a high level. The ATSB suggests that consciously self-monitoring and actively monitoring the workload of colleagues can assist a work group to better manage workload. Holding aircraft on the ground or outside the airspace are valuable tools for an air traffic controller. The ATSB also notes that flight crew operating under visual flight rules in Class C airspace should remain aware that the provision of an air traffic service does not negate their responsibility to see and avoid.

At 1503 Eastern Standard Time[1] on 24 May 2014, mutual traffic information (see the section titled Traffic information) was not passed to the flight crews of a Department of Defence (Defence) Boeing CH‑47 Chinook helicopter (the occurrence CH‑47) and a Cessna Aircraft Company 172S, registered VH‑PFU (PFU). Both aircraft were operating in the circuit area at Townsville Airport, Queensland (Figure 1). As neither flight crew were advised of the other aircraft, and aircraft proximity became a concern, the flight crew of the occurrence CH‑47 reversed the direction of their turn to remain clear.

At the time, the Defence air traffic controller with jurisdiction over the circuit area (the tower controller) had the following aircraft on frequency:

- a Defence CH‑47 operating circuits from and to a helipad 1 NM (2 km) to the west of the airfield

- a Defence Beechcraft King Air 350 (King Air) conducting circuits on runway 01[2]

- a Robinson Helicopter Co R22 (R22) operating to the south

- a McDonnell Douglas Helicopter Company 369E (MD500) inbound from the south-west

- PFU conducting circuits on runway 07

- two Defence Sikorsky Black Hawk helicopters (Black Hawks) tracking from the south to a location 2 NM (4 km) to the south-east of the airport

- the occurrence CH‑47 tracking along the coast from the east south-east to a clearance limit of Kissing Point (see the section titled Clearance limits)

- an aircraft holding on the ground for departure from runway 01.

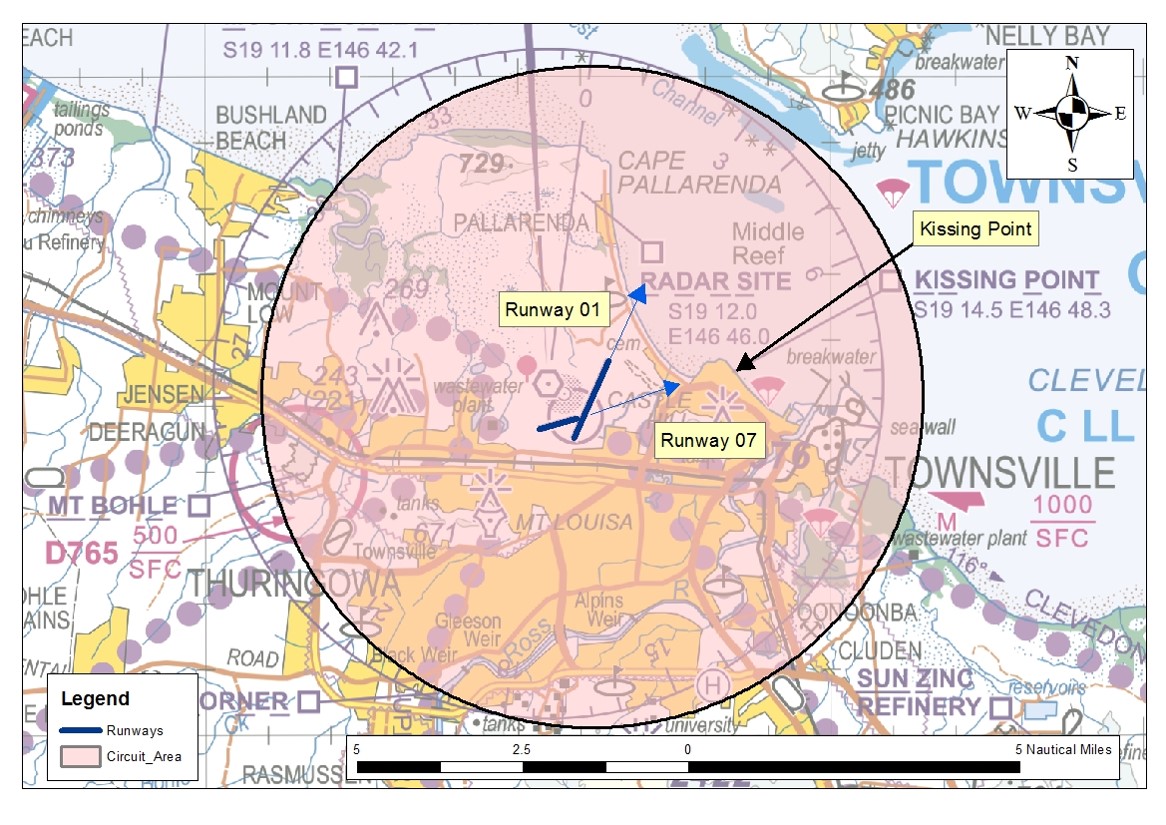

Figure 1: Townsville circuit area (shaded), showing the runways in use and Kissing Point

All of the aircraft were operating under visual flight rules (VFR)[3] in visual meteorological conditions[4] below 1,500 ft above mean sea level within the 5 NM (9 km) circuit area. The Townsville Control Tower was staffed by a tower supervisor, the tower controller and the surface movement controller.

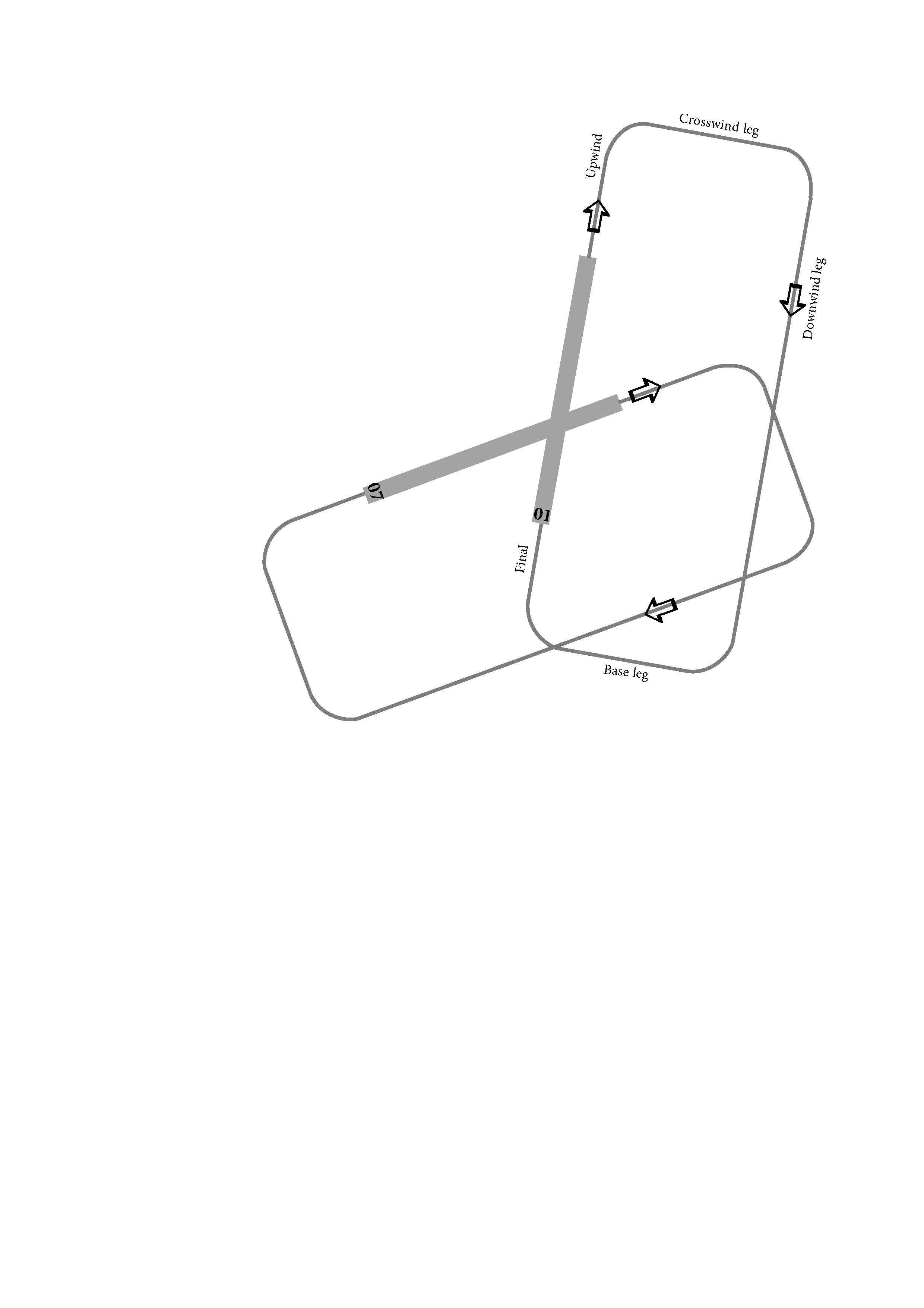

As the crosswind on runway 01 was up to 15 kt, PFU was conducting circuits on runway 07. The pilot of the King Air was conducting circuits on runway 01 (Figure 2). Both aircraft were conducting right-hand circuits, which maintained them to the east and south of Townsville Airport. To manage the sequence between the two aircraft, and to facilitate the other traffic operating within the area, the tower controller issued instructions at different times to extend various legs of the circuit. The mix of traffic under the tower controller’s jurisdiction resulted in a high workload and a high level of radio transmissions on the tower frequency.

Figure 2: Diagram showing the legs of a circuit

Source: ATSB

The CH‑47, which was operating in the circuit to the helipad to the west of the airfield, had earlier entered the circuit area via Kissing Point. The pilot of that CH-47 was advised of PFU by the tower controller on two occasions; at 1447 and at 1452. The call signs of that CH-47, which was operating to the west of the airfield, and the occurrence CH‑47 that was tracking for Kissing Point, contained the same root word with numbers that differed by one digit – Brahman 104 and Brahman 106 respectively.

At 1500, the tower controller acknowledged the first call by the flight crew of the occurrence CH‑47, when the aircraft was about 7.5 NM (14 km) to the east. No information on the traffic in the circuit area was provided to the flight crew of the occurrence CH‑47, or to any aircraft in the circuit on the occurrence CH‑47. At that time:

- PFU was on final for runway 07

- the King Air was late downwind for runway 01

- the R22 was at the southern circuit boundary

- the CH‑47 operating to the helipad to the west of the airport was on the ground awaiting clearance to become airborne

- the MD500 was about to land at Townsville

- the two Black Hawk helicopters were about 8 NM (15 km) to the south-east.

Between then and the next transmission from the flight crew of the occurrence CH‑47 to the tower controller at about 1503, there were 21 separate radio transmissions involving the tower controller and other aircraft. The second transmission from the flight crew, advising that the occurrence CH‑47 was approaching Kissing Point (Figure 1), was not acknowledged by the tower controller who then cleared the King Air to conduct a touch-and-go landing,[5] and provided tracking instructions to the crew of the R22. At this time:

- the occurrence CH‑47 was about 4.5 NM (8 km) to the east

- PFU was about 1.5 NM (3 km) upwind for runway 07

- the King Air was about 1.5 NM (3 km) final for runway 01

- the R22 was about 4 NM (7 km) to the south

- the CH‑47 operating to helipad to the west of the airfield was still on the ground awaiting clearance to become airborne

- the MD500 had landed

- the two Black Hawk helicopters were about 4.5 NM (8 km) to the south-east.

Forty-nine seconds later, the flight crew of the occurrence CH‑47 reported at Kissing Point and advised the tower controller that there was another aircraft in their vicinity. Surveillance data shows that, at that time, the occurrence CH‑47 entered a left turn towards the coastline, before reversing to the right and away from the coast and PFU.

Seeing that the occurrence CH‑47 had commenced a turn away from the PFU’s track, the tower controller did not provide traffic on PFU to the crew of the occurrence CH-47 but, instead provided traffic on the King Air, as the crew of the occurrence CH‑47 had to sight and pass behind that aircraft before it could track towards the airfield. Traffic on the occurrence CH‑47 was also not passed to the flight crew of PFU.

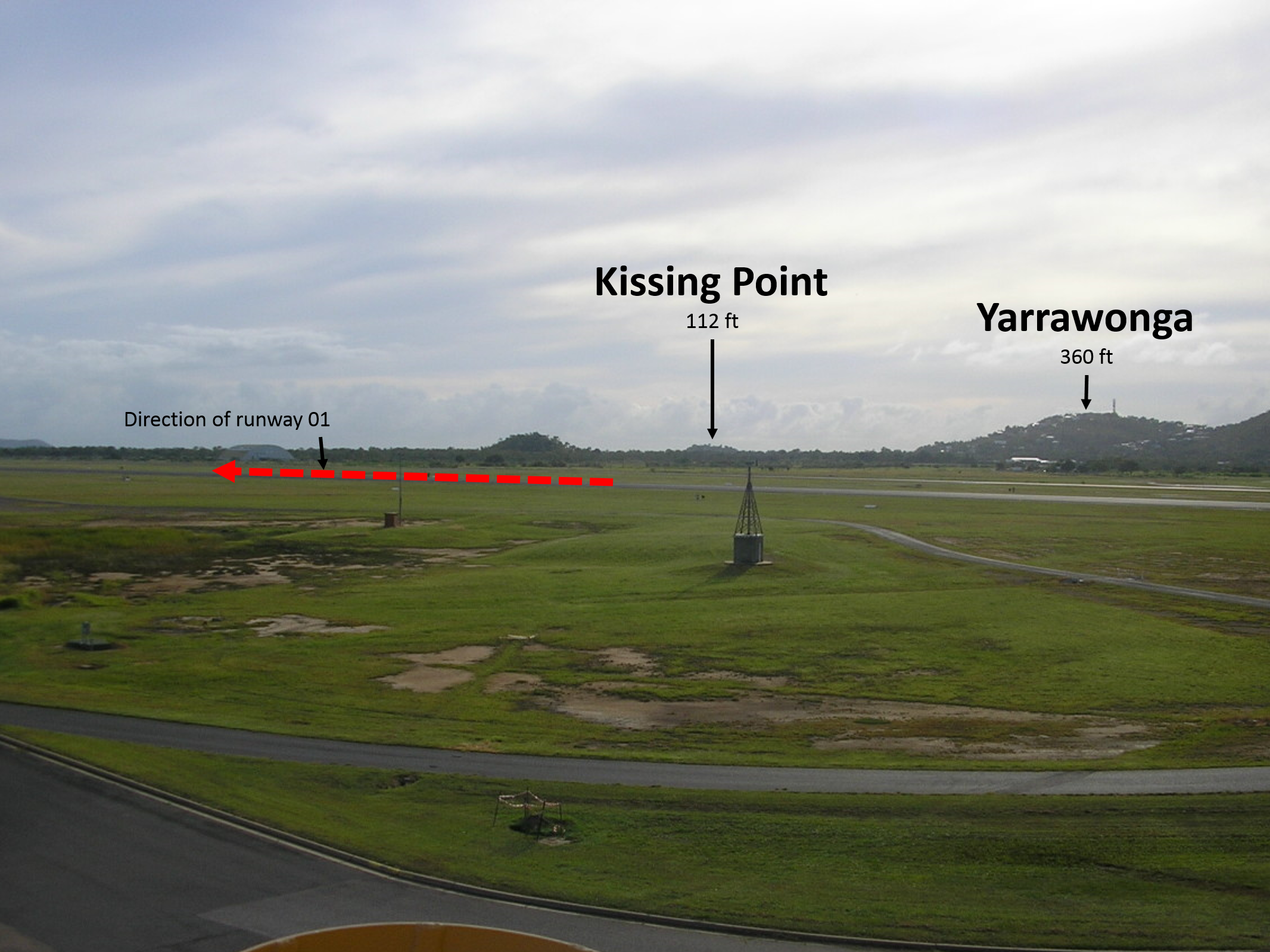

Of note, due to the topography to the east and north-east of the airport (Figure 3), and the operating height of the helicopter, the tower controller was unable to see the occurrence CH‑47 until just prior to its arrival at Kissing Point. This was the first time the tower controller was aware that the occurrence CH‑47 had an external load, requiring the controller to amend their traffic plan. The plan had been for the aircraft to track south of the airfield and fly over the city of Townsville, then to cross the upwind centreline of runway 01. With an external load, the aircraft was required to track to the west of the airport to a helipad just to the north of runway 07. This kept the occurrence CH‑47 away from built-up areas.

Figure 3: The tower controller’s view east-north-east towards Kissing Point, including relevant terrain height and the direction of runway 01

Source: Defence, modified by the ATSB

The crew of the occurrence CH‑47 subsequently sighted the King Air and tracked behind that aircraft, then to the west of the airfield for the helipad. The flight crew of PFU continued tracking upwind until advised by the tower controller to make a right circuit for runway 07.

When the flight crew of the occurrence CH‑47 first reported sighting PFU, surveillance data indicated that their aircraft and PFU were at the same altitude and separated by about 0.5 NM (1 km). However, the flight crew of the occurrence CH‑47 later reported that separation reduced to about 300 m and that, until they commenced the right turn, a collision risk had existed. The flight crew of PFU later reported that they saw the occurrence CH‑47 shortly after becoming airborne from runway 07, at a distance of 2 or 3 NM (4 or 6 km). They believed that:

- at no stage did the occurrence CH‑47 come close enough to warrant anything but monitoring

- no avoiding action was required

- no collision risk existed.

__________

- Eastern Standard Time (EST): Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) + 10 hours.

- Runway number: the number represents the magnetic heading of the runway.

- Visual flight rules (VFR): a set of regulations that permit a pilot to operate an aircraft only in weather conditions generally clear enough to allow the pilot to see where the aircraft is going.

- Visual Meteorological Conditions (VMC): weather conditions in which pilots have sufficient visibility to fly the aircraft while maintaining visual separation from terrain and other aircraft.

- Touch-and-go landing: a procedure whereby an aircraft lands and takes off without coming to a stop.

Personnel information

Townsville Tower was staffed by three Department of Defence (Defence) air traffic controllers, the:

- supervisor

- tower controller

- surface movement controller.

Each controller was correctly endorsed and no fatigue‑related issues were identified. The supervisor was also endorsed in all tower and approach positions. The tower controller and supervisor had completed the then Defence compromised separation recovery training as part of Townsville’s overall air traffic control training package, not as a stand-alone training element.

Airspace information

Defence was the controlling authority for the Class C airspace[6] around Townsville Airport and, with the circuit active, the tower controller was responsible for separating and sequencing aircraft within 5 NM (9 km) of the airport at and below 1,500 ft. The Class C airspace outside the circuit area was the responsibility of the Defence-employed approach controller. Defence controllers use the same control techniques as Airservices Australia controllers when controlling civil, or a combination of civil and military aircraft.

Procedures at Townsville permitted standard transfers of responsibility between approach and tower controllers when the circuit was active. One of these standard transfers was the use of Kissing Point as a clearance limit for helicopters tracking inbound from the east. Once the pilot of the occurrence CH-47 contacted the tower controller, irrespective of distance from Townsville Airport, the approach controller would generally have no tracking restrictions on the helicopter’s arrival. This was not the case when the helicopter was carrying an external load.

Clearance limits

A clearance limit is issued to the flight crew of an aircraft when the controller is unable to authorise an aircraft to proceed beyond a certain point or place. When a clearance limit is imposed by a controller, the flight crew must hold at that point until issued with an onwards clearance. Holding involves either a holding pattern or an orbit, which may be documented or the controller may stipulate the type and direction. Often, holding at a clearance limit is not required, as the controller is able to provide an onwards clearance prior to the aircraft reaching the limit. In these cases, the clearance limit would have been imposed to assure separation as the aircraft progressed along its track.

Separation assurance can be either strategic or tactical. Strategic separation assurance includes the development of air traffic practices to reduce the likelihood of aircraft coming into conflict, particularly where traffic frequency congestion may impair control actions. Tactical separation assurance is an activity conducted by the controller that includes traffic planning and conflict avoidance.

The Defence operational documentation for air traffic control stipulated that all military helicopters arriving at Townsville Airport from the east, when the circuit was active, would be tracked via Kissing Point. In this case, Kissing Point was stipulated as the clearance limit. The approach controller, when first contacted by the flight crew of the inbound military helicopter, would issue this clearance and clearance limit. The tower controller would then be responsible for cancelling the clearance limit and providing separation between the helicopter and all other aircraft within 5 NM (9 km) of Townsville. The documentation did not include the direction of turn for a helicopter holding at Kissing Point.

Traffic information

Traffic information is issued by an air traffic controller, to alert a pilot to other known or observed air traffic. This traffic may be in proximity to their position or intended route, and the issued traffic information helps the pilot avoid a collision. When aircraft are operating under visual flight rules (VFR) in Class C airspace, separation is not required. However, mutual traffic information is required when, in the controller’s judgement, one aircraft may observe another aircraft and could be uncertain of their intention.

Traffic information should be concise and, to assist flight crew in identifying other aircraft, may include the following information if deemed relevant by the controller:

- aircraft identification

- type and description, if unusual

- position information

- direction of flight or route of the aircraft

- level

- intentions of the pilot.

The provision of traffic information, and the content of that information, is reliant on the controller’s assessment of the underlying need. The initial provision of traffic information to the flight crew of an aircraft tracking to join the circuit could be general in nature; for example ‘the circuit is active on runway 01 and 07’. The information would then become more specific as the aircraft tracked closer to the circuit; for example, providing the type and location of those aircraft that the flight crew of the joining aircraft would encounter.

Compromised separation recovery training

Compromised separation recovery actions are important emergency response actions. They need to be implemented by controllers promptly and accurately when determined that separation standards have been, or will shortly be compromised. To ensure emergency response actions are conducted effectively, they need to be regularly practiced. Skill decay is more likely to occur when tasks are rarely performed (Arthur and others 1998), as is the case for compromised separation recovery actions during actual controlling.

Controllers are required to issue safety alerts to pilots of aircraft as a priority when the controller becomes aware that aircraft are considered to be in unsafe proximity to other aircraft. This is the case unless a pilot advises that action is being taken to resolve the situation, or that the other aircraft is in sight.

At the time of this occurrence, Defence controllers were not provided with stand-alone, regular practical refresher training in identifying and responding to compromised separation scenarios. An ATSB investigation into a loss of separation (LOS) at Williamtown (Newcastle Airport), New South Wales in 2011[7] found that Defence had not provided compromised separation recovery training as part of initial or ongoing controller training. In addition, an ATSB research report into LOS between aircraft in Australian airspace, which was released in October 2013,[8] found that controller actions to manage a compromised separation occurrence were not effective for Defence-employed controllers and those employed by Airservices Australia. Finally, after this occurrence at Townsville, in October 2014 the ATSB released a report into a LOS at Darwin, Northern Territory[9] that identified a safety issue in relation to the provision of compromised separation recovery training for Defence-employed controllers.

Related occurrences

The ATSB research report AR-2012-034 Loss of separation between aircraft in Australian airspace – January 2008 to June 2012 found that ‘assessing and planning’ or ‘monitoring and checking’ errors were involved in most individual controller actions that contributed to LOS occurrences. Ineffective management of compromised separation before it became a LOS was categorised as an assessing and planning error. Monitoring and checking errors included controller actions associated with maintaining awareness of traffic disposition.

In addition, the ATSB research report found that of the LOS occurrences in which ATC actions were contributory, about one quarter involved communication errors. These included not passing traffic information to pilots once separation was compromised. The research report found that task demands were the most common type of local condition identified in LOS occurrences where controllers were involved – in particular, high workload and distractions. Common in all ATC environments, these local conditions were more common in the tower environment.

Though this occurrence at Townsville did not involve a LOS, as no separation was required in Class C airspace between VFR aircraft, the error types are relevant. However, a review of the ATSB occurrence database did not identify any similar occurrences where mutual traffic was not provided to VFR aircraft in Class C airspace.

__________

- Class C airspace: controlled airspace surrounding major airports. All aircraft require an air traffic control clearance for operations in this airspace.

- ATSB investigation AO-2011-011 – Breakdown of separation, 22 km S Williamtown (Newcastle Airport), NSW, 1 February 2011.

- ATSB investigation AR-2012-034 – Loss of separation between aircraft in Australian airspace – January 2008 to June 2012.

- ATSB investigation AO-2012-131 – Loss of separation involving Boeing 717, VHNXQ and Boeing 737, VHVXM near Darwin Airport, Northern Territory, 2 October 2012.

Introduction

An air traffic control information error at Townsville Airport, Queensland, on 27 May 2014 involved a Department of Defence (Defence) Boeing CH-47 Chinook (the occurrence CH-47), and a Cessna 172 registered VH-PFU (PFU). The information error positioned the two aircraft in close proximity in the circuit area, without the provision of relevant traffic information.

This analysis discusses the relevant controller actions, local conditions and relevant risk controls in place at Townsville Airport at the time of the occurrence.

Traffic not passed

The number of aircraft on the tower controller’s frequency, the mix of operation types and the locations of those operations resulted in a high workload for the tower controller and tower supervisor. The tower controller reported that their workload was more than they could handle and that they asked the supervisor for assistance. The supervisor provided assistance by conducting the necessary coordination and assisting with sequencing. However, the efforts to reduce the workload, including holding aircraft on the ground and not accepting additional inbound aircraft, were not sufficient and workload remained high.

The occurrence CH‑47 was about 7.5 NM (14 km) to the east when the flight crew first contacted the tower controller. PFU was on final for runway 07. As a result, neither flight crew would have been able to sight the other. However, both flight crew were familiar with the circuit traffic pattern on runway 07, and how helicopters tracked coastal via Kissing Point. Therefore, the provision of traffic at that time would have alerted both flight crew to the presence of the other aircraft in the circuit area, and of their intentions. Of note, during this period the tower controller’s workload was high, providing tracking instructions to numerous aircraft.

The provision of traffic when the occurrence CH‑47 contacted the tower controller a second time when approaching Kissing Point, with the occurrence CH‑47 about 4.5 NM (8 km) to the east of the airfield and about 3 NM (6 km) east of PFU at that time, would have increased the likelihood of the flight crews sighting each other. The flight crew of PFU later reported that they saw the occurrence CH‑47 shortly after becoming airborne from runway 07, though they did not advise the tower controller as they were aware of the controller’s high workload at the time.

The tower controller had passed traffic to flight crews in the lead-up to this occurrence, demonstrating that they were aware of the requirement to pass traffic and of the content of traffic information. More relevant in this instance, the controller had passed mutual traffic to the flight crew of PFU and the previous CH‑47 tracking via Kissing Point. The Defence investigation into this occurrence found that the tower controller did not realise that mutual traffic had not been passed to the flight crews of the occurrence CH‑47 and PFU. The similarity in the call signs of the previous CH‑47 and the occurrence CH‑47 may have influenced the tower controller into thinking that they had passed the required traffic information.

A controller’s first priority is to separate aircraft, and then to provide traffic information. At the time the flight crew of the occurrence CH‑47 reported approaching Kissing Point, the Defence Beechcraft King Air 350 (King Air) was on about 1.5 NM (3 km) final for runway 01, awaiting a clearance for a touch-and-go landing. Also, the tower controller needed to provide tracking instructions to the flight crew of a Robinson Helicopter Co R22 that was about 4 NM (7 km) south of the airport. Additionally, a transmission from the flight crew of one of the two Defence Sikorsky Black Hawk helicopters (Black Hawk) to the south of the airport may have been sufficient to interrupt the tower controller’s activities. This would explain the controller responding to the flight crew of the Black Hawk, instead of passing traffic to the flight crews of the occurrence CH‑47 and PFU. This likely resulted in the tower controller losing awareness of the need to pass traffic to these aircraft.

If the tower controller had passed mutual traffic to the flight crews of the occurrence CH‑47 and PFU prior to the occurrence CH‑47 arriving at Kissing Point, both flight crew would have been better able to manage their flight paths in relation to the other. Additionally, had the traffic information been passed earlier, the King Air would have been the only 'relevant' traffic for the flight crew of the occurrence CH‑47 when at Kissing Point.

In this occurrence, it is likely that the tower controller’s high workload resulted in a need for increased monitoring. This would likely have further added to their workload and, in combination with the large number of radio calls during this time, impacted on their ability to manage the traffic.

Management of the proximity event

The report by the flight crew of the occurrence CH‑47 that there was an aircraft in proximity when they arrived at Kissing Point should have been a sufficient trigger to the tower controller that traffic on PFU had not been provided. However, as the controller was now aware that the flight crew of the occurrence CH‑47 had PFU in sight, and the controller could see that the occurrence CH‑47 had commenced a right turn away from the flight path of PFU, the controller deemed that traffic information was not required and that the proximity risk had been resolved. But, the flight crew of the occurrence CH‑47 were not aware of the intentions of the flight crew of PFU. Equally, the tower controller did not know if the flight crew of PFU had seen, and were monitoring the occurrence CH‑47. The flight crew of the two aircraft determined their own actions based solely on what they could observe of the other aircraft.

Compromised separation recovery training

A conflict occurs when the distance between aircraft, as well as their relative positions and speed, may compromise the safety of the aircraft. On recognising such a situation, the controller is required to issue a safety alert, unless the pilot of one aircraft advises that action is being taken to resolve the situation, or that the other aircraft is in sight. The tower controller reported that in this case, both aircraft were in sight and the controller and supervisor both assessed that, as the flight crew of the occurrence CH‑47 had reported PFU in sight and turned away, the safety of neither aircraft was compromised.

At the time of the occurrence, compromised separation recovery training deficiencies had been identified and were being addressed within Defence. Though there is insufficient evidence that these deficiencies played a part in this occurrence, such training is an important defence against loss of separation and near-collision situations.

Advance knowledge of external load operations

Defence helicopter documentation for operations at Townsville Airport stipulated that, when operating with external loads, the helicopter should be flown clear of built-up or populated areas. Specifically, flight over people, buildings, vehicles or items of value must only occur if totally unavoidable. These precautions mitigated the risk of injury or damage in the event of accidental or emergency load release. In the context of the Townsville circuit area, these operating requirements meant that Defence helicopters carrying out external load operations were to track coastal until north-west of the extended centreline of runway 01, then along the western side of the airport to one of a number of helipads.

Though the tower controller and tower supervisor were aware of these requirements, until the tower controller sighted the occurrence CH‑47 approaching Kissing Point, they were not aware that it had an external load. The intended traffic sequence required the occurrence CH‑47 to track from Kissing Point south to right base for runway 01, then across runway 01 to land on the helipad just north of runway 07. On sighting the occurrence CH‑47 carrying an external load, the tower controller’s traffic plan had to be amended to track the helicopter away from built-up areas.

A documented procedure that required helicopter crews to advise air traffic control that they were carrying an external load, which could restrict manoeuvring, would result in better situation awareness for tower controllers and better inform their traffic management planning. In this occurrence, such additional information would likely have precluded the need for the tower controller to rapidly re-assess the disposition of the circuit traffic and to require the occurrence CH‑47 to sight and pass behind the King Air.

Kissing Point as a clearance limit

The Defence Townsville documentation that stipulated Kissing Point as a clearance limit was a form of strategic separation assurance. However, Kissing Point is located within the 5 NM (9 km) circuit area on the extended centreline of runway 07 (see Figure 1), 3 NM (6 km) east of Townsville. A standard clearance limit located further from Townsville would have provided better separation assurance between joining aircraft and those in the circuit area.

Though there was no evidence that a clearance limit further from Townsville would have avoided this proximity event, the controller is only part of a wider system designed to provide for safe aviation operations. A well-designed system should include strategic separation assurance that supports the controller. This could include holding aircraft in locations away from known high traffic areas, where the absence of one component (in this case the provision of mutual traffic) does not result in a compromised safety system.

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the air traffic control information error involving a Department of Defence Boeing CH‑47 Chinook helicopter and a Cessna Aircraft Company 172S, registered VH‑PFU, near Townsville Airport, Queensland on 27 May 2014. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

Safety issues, or system problems, are highlighted in bold to emphasise their importance. A safety issue is an event or condition that increases safety risk and (a) can reasonably be regarded as having the potential to adversely affect the safety of future operations, and (b) is a characteristic of an organisation or a system, rather than a characteristic of a specific individual, or characteristic of an operating environment at a specific point in time.

Contributing factors

Due to the busy environment, and possibly the similarity between two Boeing CH‑47 Chinook helicopter call signs, the controller did not pass mutual traffic and was not monitoring the occurrence helicopter and the Cessna Aircraft Company 172S in case of a proximity event.

The tower controller and tower supervisor assessed that, as the occurrence Boeing CH‑47 Chinook helicopter flight crew had identified the Cessna Aircraft Company 172S in proximity and had initiated a turn away, the proximity event was resolved. This meant that the flight crew of the two aircraft had to determine their own actions based solely on their observation of the other aircraft.

Other factors that increased risk

Compromised separation recovery training deficiencies existed within the Department of Defence at the time of the occurrence, increasing the risk of inappropriate management of aircraft in close proximity. [Safety issue]

Helicopter flight crews were not required to advise the tower controllers of the carriage of external loads that prevented them flying over built-up areas. This reduced the controller’s situation awareness and reduced the time available to develop an appropriate traffic management plan.

The location of the Kissing Point clearance limit within the Townsville circuit area increased the risk of an aircraft holding at that position coming into proximity with aircraft operating in the circuit.

The safety issues identified during this investigation are listed in the Findings and Safety issues and actions sections of this report. The ATSB expects that all safety issues identified by the investigation should be addressed by the relevant organisation(s). In addressing those issues, the ATSB prefers to encourage relevant organisation(s) to proactively initiate safety action, rather than to issue formal safety recommendations or safety advisory notices.

All of the directly involved parties were provided with a draft report and invited to provide submissions. As part of that process, each organisation was asked to communicate what safety actions, if any, they had carried out or were planning to carry out in relation to each safety issue relevant to their organisation.

The initial public version of these safety issues and actions are repeated separately on the ATSB website to facilitate monitoring by interested parties. Where relevant the safety issues and actions will be updated on the ATSB website as information comes to hand.

Compromised separation recovery training

Compromised separation recovery training deficiencies existed within the Department of Defence at the time of the occurrence, increasing the risk of inappropriate management of aircraft in close proximity.

Note: This safety issue was identified as part of ATSB investigation AO-2012-131 as safety issue AO-2012-131-SI-05 and resulted in the ATSB issuing safety recommendation AO‑2012‑131‑SR‑042 on 2 October 2014 (after the date of this occurrence at Townsville). The information below is a summary of the action taken by the Department of Defence (Defence) at that time. That action resulted in the ATSB determining that, overall, the safety action by Defence adequately addressed safety issue AO-2012-131-SI-05.

Aviation safety Issue: AO-2014-096 -SI-01

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included the:

- Department of Defence

- air traffic controllers involved in the incident

- flight crew of VH-PFU

- flight crew of the occurrence Boeing CH‑47 Chinook helicopter.

References

Arthur, W Bennett, W Stanush, PL & McNelly, TL 1998, Factors that influence skill decay and retention: A quantitative review and analysis, Human Performance, vol. 11, pp. 57–101.

Submissions

Under Part 4, Division 2 (Investigation Reports), Section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 (the Act), the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. Section 26 (1) (a) of the Act allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the Department of Defence, the Civil Aviation Safety Authority, the air traffic controllers involved in the occurrence, the operator of VH-PFU and the flight crews of the occurrence Boeing CH‑47 Chinook helicopter and of VH‑PFU.

Submissions were received from the Department of Defence and the Civil Aviation Safety Authority. The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2016

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |