What happened

On 9 September 2012, a Boeing 747 freight aircraft, operated by Atlas Air and registered N409MC, was approaching runway 34 at Melbourne Airport, Victoria, following a flight from Auckland, New Zealand.

The flight crew was conducting the LIZZI FIVE VICTOR standard arrival route (STAR) procedure that included a requirement not to descend below 2,500 ft until past the SHEED waypoint. They were issued clearance by air traffic control for a visual approach for runway 34 from the SHEED waypoint, conditional on not descending below 2,500 ft before SHEED. The flight crew read back the clearance without including the minimum altitude before passing SHEED and the controller did not query the incomplete read back. The flight crew initiated the visual approach and descended below the stipulated minimum of 2,500 ft prior to SHEED.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that the United States-based flight crew did not hear the requirement of the clearance to not descend until after passing the SHEED waypoint. Instead, they read back what they believed to be a clearance for an immediate visual approach from their present position. This is a normal instruction during operations in United States airspace. The crew continued their approach to Melbourne Airport based on this understanding. There was no loss of separation with any aircraft.

The lack of detection by the controller of the crew’s incomplete read back represented a missed opportunity to alert the flight crew to not descend below 2,500 ft until after the SHEED waypoint.

Visual approaches from STARs are available elsewhere in Australia, but are not available for use by international operators of large jet aircraft. The approaches via SHEED to runway 34 at Melbourne are the only exception to this rule and are implemented with few additional defences to address the increased risk associated with this type of approach. In addition, the flight profile required from the SHEED waypoint to runway 34 is steeper than other approaches of this type in Australia, requiring a higher rate of descent. This increases the likelihood of an unstable approach.

What’s been done as a result

As a result of this occurrence, Airservices Australia (Airservices) is removing the provision in the Manual of Air Traffic Services for international Heavy and Super Heavy aircraft to use the SHEED visual segment. This permanent change to the Manual of Air Traffic Services is planned for November 2015, with a temporary local instruction to that effect to be issued by Airservices in the interim. In respect of the descent profile of the LIZZI FIVE RWY 34 VICTOR ARRIVAL, the Civil Aviation Safety Authority will engage with Airservices to ensure that the procedure meets all relevant instrument procedure design and ‘flyability’ standards.

Safety message

This occurrence highlights the importance of a shared understanding of a clearance between pilots and air traffic controllers, and the factors which may affect this understanding. It also underlines the importance of a thorough risk assessment in support of the design, modification and promulgation of approaches so that any increased risk is identified and addressed.

On 9 September 2012, the flight crew of a Boeing 747-47 UF/SCD freight aircraft, registered N409MC and operated by Atlas Air Inc. (Figure 1), conducted a flight from Honolulu, United States (US), to Auckland Airport, New Zealand. From Auckland the flight continued to Melbourne Airport, Victoria, with an estimated time of arrival of about 1800 Eastern Standard Time.[1] The aircraft was being operated as a freight flight for an Australian operator and had four US flight crew on board due to the length of the flight.

Figure 1: B747, US-registered N409MC

Source: Xing Li

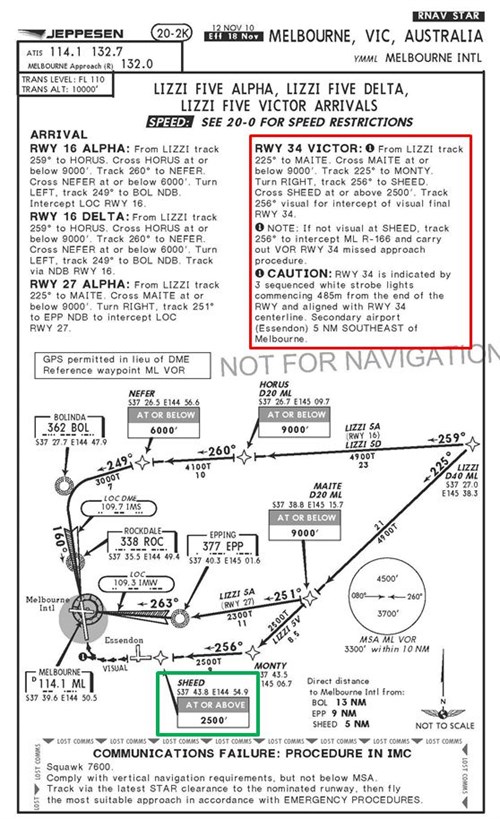

As the aircraft tracked towards Melbourne, the crew were cleared by air traffic control (ATC) to conduct a LIZZI FIVE VICTOR standard arrival route (STAR) for the descent from cruising altitude to the landing (Figure 2). The first officer was the pilot flying and the captain the pilot not flying.

At 1720 the crew specified a requirement to ATC for them to use runway 34 instead of runway 27 which, due to the generally more favourable winds affecting that runway, was also in use. The crew reported that their requirement was based on the greater runway length available on runway 34, and the aircraft’s high landing weight. At 1724, ATC asked the crew if they were prepared to accept the visual approach that formed the final segment of the STAR. The crew confirmed that they could accept the visual approach.

Figure 2: LIZZI FIVE ALPHA, DELTA AND VICTOR STAR ARRIVALs chart (RWY 34 VICTOR, which incorporates the SHEED waypoint, highlighted in red and the position of waypoint SHEED highlighted in green)

Source: Jeppesen (modified by the ATSB)

At 1735, as the aircraft descended through flight level (FL) 200[2] and passed 65 NM (120 km) from Melbourne, the crew requested a change of approach to an area navigation global navigation satellite system (RNAV GNSS) instrument approach. This approach provided for an 8 NM (14.8 km) final approach track to runway 34. The crew reported requesting this approach because of the atmospheric haze and the setting sun to the west, which reduced their forward visibility. The crew were informed by ATC that unless they advised that the change was an ‘operational requirement’ their request for the RNAV GNSS approach was not available. ATC was concerned that the change would have caused delays to the arrival sequence of following aircraft.

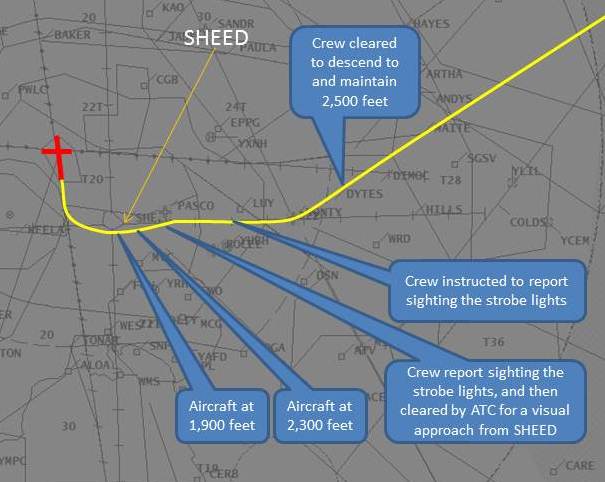

The crew confirmed acceptance of the original clearance via the LIZZI FIVE VICTOR STAR and by implication the associated visual segment. ATC cleared the crew to continue their descent to progressively lower altitudes before instructing them to ‘descend to and maintain 2,500 ft’ (Figure 3). The flight crew read back the clearance to descend to 2,500 ft but not the requirement to maintain that altitude.

Figure 3: Aircraft radar track

Source: Airservices Australia (modified by the ATSB)

Visual guidance to runway 34 was provided by sequenced lead-in strobe lights to assist crews conduct a visual turn onto final and a precision approach path indicator (PAPI) system for approach slope guidance[3]. At 1747, when the aircraft was 7 NM (13 km) from the airport, ATC instructed the crew to report sighting the lead-in strobe lights. At that time the aircraft was about 4 NM (7.4 km) from the SHEED waypoint, which was located at the threshold of runway 27 at Essendon Airport. SHEED was the final waypoint before the visual segment of the STAR procedure. Recorded radar data showed the aircraft deviating left of track from about 3 NM (5.5 km) before SHEED, which the flight crew reported was to provide ‘more room’ for descent during the visual segment of the STAR.

The LIZZI FIVE VICTOR STAR had a minimum altitude restriction that required aircraft to cross the SHEED waypoint at or above 2,500 ft (Figure 2). The STAR procedure stated that if the flight crew had not obtained visual reference at SHEED, they were to initiate a missed approach procedure (Figure 2).

At 1748, when the aircraft was about 1 NM (1,852 m) before SHEED, the controller asked the flight crew if they had seen the lead-in strobe lights. The crew reported sighting the strobe lights, having just observed them. The controller then instructed the flight crew ‘…from SHEED you’re cleared visual approach for runway three four’. The crew read back ‘clear visual’ and configured the aircraft for the approach by extending the landing gear and approach flap. The first officer also disengaged the autopilot and initiated a descent for the visual approach. The controller did not query the flight crew in relation to providing a corrected read back to include the conditional clearance that descent below 2,500 ft was only authorised ‘…from [after passing] SHEED’.

At about 1749 the aircraft descended below 2,500 ft when still about 1.6 km before SHEED and was descending through 1,900 ft when passing abeam SHEED. The aircraft’s maximum deviation to the left of the arrival track was about 500 m. The pilot of a helicopter operating at 1,500 ft in the Essendon control zone saw the B747, thought it was lower than expected and descended the helicopter to 1,000 ft to ensure adequate separation.

The aircraft landed on runway 34 at 1751.

__________

- Eastern Standard Time (EST) was Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) + 10 hours.

- At altitudes above 10,000 ft in Australia, an aircraft’s height above mean sea level is referred to as a flight level (FL). FL 200 equates to 20,000 ft.

- The visual approach guidance provided by the runway 34 Precision Approach Path Indicator (PAPI) was set at a 3° descent path.

Personnel information

The flight crew consisted of four pilots comprising the captain, first officer and two cruise relief pilots. The cruise relief pilots operated the aircraft in the cruise phase between Honolulu and Auckland to enable the operating crew to rest during this time. The cruise relief pilots were seated on the flight deck, behind the captain and first officer during the approach and landing at Melbourne.

The captain held a United States (US) Airline Transport Pilot certificate and was type rated on the Boeing 747 aircraft. He had a total aeronautical experience of over 20,000 hours including over 10,000 hours on Boeing 747 aircraft. The captain reported flying into Melbourne Airport ‘many times before’.

The first officer also held an Airline Transport Pilot certificate and was type rated on the Boeing 747 aircraft. He had a total aeronautical experience of about 8,000 hours including about 400 hours flying the B747 aircraft type with this operator. The occurrence flight was the first time that the first officer had flown into Melbourne Airport.

Three days before the occurrence flight, the crew conducted a 9-hour flight between Chicago and Honolulu, US. They then had 36 hours rest before starting the flight duty period flying to Auckland and then on to Melbourne.

Under US 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 117FLIGHT AND DUTY LIMITATIONS AND REST REQUIREMENTS: FLIGHTCREW MEMBERS, a flight crew member could not accept an assignment or continue an assigned flight duty period if the total flight time exceeded 19 hours for a 4-pilot flight crew operation. The assigned flight duty period from Honolulu via Auckland to Melbourne was less than 19 hours.

The flight crew reported being well rested before the flight. The captain reported feeling ‘fine’ at the time, having 4-5 hours rest during the first leg of the flight. The first officer reported having about 2.5 hours of sleep during the first leg of the flight.

Analysis of the crew’s fatigue-related information showed that at the time of the occurrence, the operating flight crew would have been tired, consistent with a long flight duty period. However, it was assessed that fatigue was not an issue in the occurrence event.

Meteorological information

The relevant aerodrome forecast indicated a headwind of 10 kt at ground level as the aircraft approached the SHEED waypoint, with Few[4] clouds at 4,400 ft above aerodrome level (AAL). The aerodrome weather report and associated trend forecast issued shortly after the aircraft landed indicated nil wind, no cloud below 5,000 ft AAL and a horizontal visibility of 10 km or greater.

The position of the sun was 17° above the horizon and 35° to the right of the aircraft’s track as the aircraft overflew SHEED. The position of the sun would have added to the effect of any haze, impacting on the crew's ability to identify the lead-in strobe lights as the aircraft approached SHEED.

Standard arrival route procedures

Standard arrival routes (STAR) are pre-planned arrival routes that link en route airways systems to a fix or waypoint at or near the destination airport. STARs are used by the pilots of instrument flight rules aircraft in order to reduce pilot/controller workload and air/ground communication requirements.

STARs with visual segments to runway thresholds have a waypoint for the transition to the visual segment. For the LIZZI FIVE VICTOR STAR to runway 34, SHEED was the waypoint for transition. The required descent path angle from crossing SHEED at 2,500 ft to the runway 34 threshold at Melbourne Airport was 3.5°. This contrasted with the 3° descent path angle normally used for visual and instrument landing system (ILS)[5] approaches.

An ATSB review of STAR procedures for jet aircraft at major Australian airports identified a total of 24 STARs that incorporated visual segments. These included at Adelaide, Brisbane, Cairns, Gold Coast, Melbourne and Perth Airports. Most of these STARs, including the LIZZI FIVE VICTOR STAR, aligned the aircraft to intercept the final approach at between 2 NM (3.7 km) and 5 NM (9.3 km) from the respective runway threshold.

There were three STARs for jet aircraft via the SHEED waypoint, including the LIZZI FIVE VICTOR. Each had a visual segment with a descent path angle greater than 3°.

ATC clearances for STARs with a visual segment

The air traffic control (ATC) practices for aircraft operating on STAR procedures are contained in the Manual of Air Traffic Services (MATS). MATS is a joint Airservices Australia and Department of Defence publication for use in the provision of air traffic services in Australian airspace. This includes by civilian and military ATC.

MATS Chapter 9-15 Control Practices stated that in relation to STAR clearances with a visual segment:

With the exception of Australian and New Zealand operators, do not assign Super or Heavy jet aircraft the visual segment of a STAR.

Note: this restriction does not apply to STARs via SHEED at Melbourne, in regular use by foreign carriers.

For the purpose of this control restriction, the Boeing 747 was categorised as a Heavy[6] jet aircraft and Atlas Air was considered to be a foreign carrier that regularly used STARs via SHEED.

At interview, the Melbourne approach air traffic controller reported that it was normal practice to use a different clearance format for flight crew of foreign aircraft that were conducting a visual approach from SHEED to runway 34. Those flight crew were given a clearance ‘…descend to and maintain 2,500’ and instructed to report sighting the lead-in strobes. Once the lead-in strobes were reported in sight, the flight crew were instructed ‘…from SHEED cleared visual approach runway 34.’ This format differed from clearances given to flight crews of Australian and New Zealand operators, who were usually cleared ‘…descend to 2,500, from SHEED cleared visual approach runway 34.’

The intent of this practice was to provide clearances to foreign flight crews in smaller chunks of information and reinforce the descent limitations prior to passing overhead SHEED. The effect of the clearance sequence was for foreign flight crews to conduct a step down procedure, unlike the continuous descent profile possible by domestic and New Zealand crews.

The differing format of issuing clearances to foreign crews for visual approaches from SHEED to runway 34 was not documented in the air traffic services internal procedures or instructions.

ATC risk mitigation for STARs with a visual segment

STARs that included a final visual approach segment to a landing allowed a shorter approach, fewer aircraft track miles and less traffic congestion in busy terminal airspace. They were suitable for use in visual meteorological conditions (VMC)[7] so that pilots could accurately intercept the final approach path closer to the touchdown point.

The STAR clearance control practices in the MATS addressed the risk associated with flight crews who were less familiar with the specific approaches manoeuvring closer to the runway threshold in larger aircraft with high inertia and less manoeuvrability. They applied to all STARs except those that tracked via the SHEED waypoint for a visual approach to runway 34 at Melbourne.

No additional procedural risk mitigations were applied to visual approaches from SHEED involving foreign crews in ‘heavy’ aircraft.

LIZZI FIVE VICTOR STAR and separation assurance

Local letters of agreement between Melbourne Approach and Essendon Tower allowed Melbourne Approach to clear an aircraft to descend to 2,500 ft between MONTY and SHEED, if runway 34 was a nominated duty runway for Melbourne Airport. The LIZZI FIVE VICTOR STAR minimum altitude of 2,500 ft overflying SHEED was to provide 1,000 ft vertical separation between overflying aircraft and aircraft operating at Essendon Airport. Aircraft operating at Essendon Airport were cleared to a maximum altitude of 1,500 ft.

Once an overflying aircraft passed SHEED, separation assurance between the overflying aircraft and local Essendon Airport traffic was provided by Essendon tower controllers. The controllers maintained visual separation by directing Essendon Airport traffic that were operating on the Essendon tower frequency away from the intended path of overflying traffic. Overflying traffic was operating on the Melbourne Approach or Tower frequencies.

Alternative STAR procedures for Melbourne runway 34

Another STAR procedure was available at Melbourne that allowed aircraft to be tracked for an area navigation global navigation satellite system (RNAV GNSS) approach for runway 34. This procedure aligned the aircraft with the runway centre-line and on the descent profile by 8 NM (14.8 km) from the touchdown zone.

Operational information

Visual approach clearance

The crew reported regularly flying to a number of different countries. They stated that their experience was that the air traffic services of different countries were conducted in accordance with International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) standards. But, there were differences in achieving these standards.

The captain, who was more experienced than the first officer in Australian operations, reported that Australian air traffic controllers cancelled a STAR clearance before providing clearance to navigate by a different means. The captain stated that in the US, clearance for a visual approach by an aircraft on a STAR meant that the crew were cleared to deviate from the original clearance at that point. US-documented procedures indicated that the international standard phraseology of ‘Cancel STAR’ was not used in the US. In accordance with normal protocol, this US ‘difference’ in standard phraseology had been notified to ICAO.

Neither the captain nor the first officer reported hearing ‘…from SHEED,…’ element of their clearance before the phrase ‘…cleared visual approach for runway 34.’ Both flight crew reported interpreting the clearance as one that cancelled restrictions associated with the STAR and cleared them to resume visual navigation to a landing on runway 34. In contrast the controller, based on the clearance provided, expected the flight crew to not descend below 2,500 ft until passing the SHEED waypoint.

The MATS and the Aeronautical Information Publication Australia required safety-related parts of any clearance or instruction to be read back by the pilot to the controller. The MATS Part 915 Control practices stated:

Obtain a readback in sufficient detail that clearly indicates pilot’s understanding of and compliance with all ATC clearances, including conditional clearances, instructions and information which are transmitted by voice.

If a controller did not detect and correct an erroneous or incomplete read back it could result in deviations from the assigned altitude or non-compliance with altitude restrictions or radar vectors. In these cases, deviations from a clearance or instruction may not be detected until a controller observes the deviation on their air situation display.

Stabilised visual approach criteria

In VMC, the aircraft operator required its flight crew to establish the Boeing 747 aircraft on a stabilised final approach by 500 ft above the runway threshold elevation. Unless special circumstances existed, the operator’s stabilised approach criteria included the aircraft being in the landing configuration with a rate of descent no greater than 1,000 ft/min by that height.

The descent path angle to the runway threshold when overflying SHEED at 2,500 ft was 3.5°.[8] In order to fly the approach, it was necessary to descend from SHEED at about 1,000 ft/min, then conduct a right turn to intercept the runway 34 extended centre-line while decelerating to the final approach speed. This manoeuvre allowed the aircraft to be aligned with the runway by 800 ft altitude, which was 500 ft above the runway threshold elevation. The descent profile was steeper than normal until about 2 NM (3.7 km) from the runway threshold.

Constant-angle approach profiles

The Flight Safety Foundation Approach and Landing Accident Reduction Tool Kit included a briefing note about the conduct of non-precision approaches and the benefits of a constant angle approach compared with a step-down approach. The briefing note stated:

Traditional step-down approaches are based on an obstacle clearance profile; such approaches are not optimum for modern turbine aircraft and turboprop aircraft.

Flying a constant-angle approach profile:

- Provides a more stabilized approach path;

- Reduces workload; and,

- Reduces the risk of error.

The clearances provided by ATC to foreign flight crews conducting the LIZZI FIVE VICTOR STAR required the aircraft to be flown in a step-down profile. While this practice was used by ATC as a defence against an early descent by foreign flight crew, it did not allow the crew to fly the procedure as a constant-angle approach profile.

Australian operator review of visual approaches from SHEED

Due to concerns about visual approaches to runway 34 from the SHEED waypoint, an Australian operator of high-capacity passenger aircraft initiated a flight data analysis of these approaches by a range of aircraft types over a period of time. The analysis identified differences between visual approaches from SHEED and other approaches to Melbourne. No risk was identified that justified specific mitigation.

The Australian operator continues to monitor flight data for its use of this approach and has modified its simulator training to ensure flight crews have adequate exposure to the approach. Advice has been provided by the operator to flight crew to alert them to the risk profile associated with this approach. Crews are only to accept clearance changes that are suitable to the handling requirements for the descent profile and the prevailing wind conditions.

A second Australian operator of high-capacity passenger aircraft developed guidance material for their flight crew in relation to approaches via SHEED. This included information from their flight data monitoring program, which had identified events involving high rates of descent below 1,000 ft. Descents from SHEED were listed as a contributor in a number of these events.

In addition, this and other guidance material emphasised the increased descent rate necessary from SHEED as a result of the 3.5° descent path angle. The second operator developed simulator training material and guidance for flight crew on the conduct of this arrival and placed a limitation on the conduct of this approach by some in its fleet of aircraft types.

Related occurrences

A review of the ATSB’s occurrence database as part of this investigation showed that since January 2008, there were nine other reported occurrences where flight crew descended below 2,500 ft before passing the SHEED waypoint. Of these, five involved foreign flight crew.

__________

- Cloud cover is normally reported using expressions that denote the extent of the cover. The expression Few indicates that up to a quarter of the sky is covered.

- For the purpose of wake turbulence separation, ‘heavy’ aircraft have a maximum take-off weight of 136,000 kg or more.

- A set of in-flight conditions in which flight under the visual flight rules is permitted—that is, conditions in which pilots have sufficient visibility to fly the aircraft maintaining visual separation from terrain and other aircraft.

- In order to fly a 3.0° descent path, an aircraft needed to overfly SHEED at about 2,200 ft, which breached the 2,500 ft altitude requirement overhead SHEED.

Introduction

During approach into Melbourne Airport, Victoria on 9 September 2012, the Boeing 747 aircraft descended below the minimum permitted altitude for the final segment of a standard arrival route (STAR) prior to landing at Melbourne. A number of factors influenced this descent and are discussed in the following analysis.

The approach

The flight crew were initially issued with the STAR clearance involving a visual final segment by air traffic control (ATC) after they requested an approach to runway 34 instead of runway 27. During the descent, and prior to commencing the STAR, the flight crew requested an area navigation global navigation satellite system (RNAV GNSS) approach. ATC advised that this approach was not available unless it was an operational requirement. The captain related a concern about the prevailing visibility, to which ATC responded that the visibility should improve as they neared the airport. In response the flight crew decided to continue with the STAR and visual approach.

During this approach, ATC issued the clearance ‘from SHEED, cleared visual approach’. However, the crew did not read back the full clearance, omitting the ‘from SHEED’ condition issued by ATC. This condition only allowed them to commence the visual approach once they passed the SHEED waypoint. The clearance was provided at the same time that the crew sighted the lead-in strobe lights, for which they had been actively searching to assist their turn onto final. It also occurred close to the point where a missed approach procedure would be required had the lights not been sighted. It is possible that the activity of searching for the lights, particularly in the reported hazy conditions, and the preparation for a potential missed approach drew the crew’s attention away from monitoring their vertical position on the approach.

Additionally, as the flight crew were United States (US)-certificated, they were used to the normal practice in US airspace of STAR clearances being cancelled implicitly by the provision of new clearances. In Australian airspace, an aircraft remains on a STAR until ATC transmits ‘Cancel STAR’ and provides further instructions, or until the aircraft reaches the end of the published STAR procedure. While the captain had flown into Australia ‘many times’ previously, this was the first time in Australian airspace for the first officer. The first officer reported believing that any restrictions associated with a STAR no longer applied once cleared for a visual approach.

The flight crew’s shared mental model of the ability to descend on receipt of a new clearance (in this case for the visual approach) was inconsistent with that of the air traffic controller. The controller was not expecting the flight crew to descend below the minimum height before passing the SHEED waypoint, as stipulated in the STAR procedure. While the flight crew’s understanding was consistent with the procedures used in US airspace, these did not apply in Australia, leading to the descent below the minimum permitted altitude.

Air traffic control clearance procedures

The standard risk mitigation for ensuring that a clearance was understood by flight crews was for the flight crew to read back the clearance to the controller and for the controller to correct any errors. The flight crew’s read back of the clearance for the visual approach to runway 34 from the SHEED waypoint was incomplete. The controller did not detect the omission and the crew’s misunderstanding of the visual approach clearance remained undetected by the flight crew. Consequently, the flight crew followed their understanding of the clearance as it applied in the US, and descended below the cleared minimum of 2,500 ft before the SHEED waypoint.

If the controller had recognised and challenged the incomplete read back, it is likely that the flight crew would have been alerted to the need to maintain 2,500 ft until passing SHEED.

Approach design and approval

The design of the LIZZI FIVE RWY 34 VICTOR ARRIVAL necessitated a descent profile of 3.5° for the visual approach from SHEED to the runway 34 threshold. A review of exceedances at SHEED by other operators highlighted that this increased angle resulted in higher descent rates, often in excess of 1,000 ft/min. This is the recommended maximum rate of descent for a stabilised approach. A higher descent rate increases the likelihood of an unstable approach during the descent from overhead the SHEED waypoint.

During the approach, the aircraft was descended to about 1,900 ft over the SHEED waypoint, which was about 600 ft below the minimum altitude at that position. A review of similar occurrence events found that other aircraft had also overflown SHEED at about this altitude. This lower altitude was consistent with a 3° descent profile for a landing on runway 34 and with the first officer’s recollection of commencing a 3° descent profile once they believed they were cleared to descend.

There were a number of control practices restrictions in the Manual of Air Traffic Services (MATS) in relation to ATC issuing STAR clearances with a visual segment to foreign operators of heavy or super jet aircraft. These restrictions would have precluded this aircraft from conducting a STAR with a visual segment at other locations in Australia. However, MATS allowed the SHEED visual approach by foreign operators if they were familiar with its conduct, and this operator was considered to meet this requirement.

Aside from an undocumented local control procedure for application to the SHEED visual approach by foreign operators of heavy or super jet aircraft, there were no alternative or additional defences to support this variation in control practice. In addition, the local control procedure required the flight crew to stop descending before SHEED, report sighting the lead-in strobe lights and then recommence the descent once the aircraft had passed SHEED. This resulted in the foreign crews conducting a step-down descent profile. While this sequential clearance was a considered decision by ATC in order to minimise the risk of foreign flight crew misinterpreting the approach or descending prior to SHEED, it negated the inherent protections of a constant angle descent profile. The importance of constant-angle approaches was highlighted by the Flight Safety Foundation in their Approach and Landing Accident Reduction Tool Kit as a defence against unstable approaches and controlled flight into terrain.

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the descent below minimum permitted altitude involving Boeing 747 registered N409MC that occurred near Melbourne Airport on 9 September 2012. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

Safety issues, or system problems, are highlighted in bold to emphasise their importance. A safety issue is an event or condition that increases safety risk and (a) can reasonably be regarded as having the potential to adversely affect the safety of future operations, and (b) is a characteristic of an organisation or a system, rather than a characteristic of a specific individual, or characteristic of an operating environment at a specific point in time.

Contributing factors

- The flight crew did not perceive the clearance requirement to not descend below 2,500 ft until passing the SHEED waypoint and descended prior to this point.

- Air traffic control did not detect or correct the flight crew's incomplete read back of the clearance for the visual approach to runway 34 from the SHEED waypoint, missing an opportunity to prevent the descent prior to the SHEED waypoint.

- Unlike other Australian standard arrival routes that included a visual segment, the visual approach to runway 34 at Melbourne via the SHEED waypoint could be issued to super or heavy jet aircraft operated by foreign operators, despite there being more safety occurrences involving the SHEED waypoint than other comparable approaches. [Safety issue]

Other factors that increased risk

- The LIZZI FIVE RWY 34 VICTOR ARRIVAL required a 3.5° descent profile after passing the SHEED waypoint for visual approach to runway 34 at Melbourne, increasing the risk of an unstable approach. [Safety issue]

The safety issues identified during this investigation are listed in the Findings and Safety issues and actions sections of this report. The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) expects that all safety issues identified by the investigation should be addressed by the relevant organisation(s). In addressing those issues, the ATSB prefers to encourage relevant organisation(s) to proactively initiate safety action, rather than to issue formal safety recommendations or safety advisory notices.

All of the directly involved parties were provided with a draft report and invited to provide submissions. As part of that process, each organisation was asked to communicate what safety actions, if any, they had carried out or were planning to carry out in relation to each safety issue relevant to their organisation.

Where relevant, these safety issues and actions will be updated on the ATSB website as information comes to hand. The initial public version of these safety issues and actions are in PDF on the ATSB website.

Assigning approaches to foreign operators

Unlike other Australian standard arrival routes that included a visual segment, the visual approach to runway 34 at Melbourne via the SHEED waypoint could be issued to super or heavy jet aircraft operated by foreign operators, despite there being more occurrences involving the SHEED waypoint than other comparable approaches.

Safety issuer: AO-2012-120-SI-01

Design of the LIZZI FIVE RWY 34 VICTOR ARRIVAL at Melbourne Airport

The LIZZI FIVE RWY 34 VICTOR ARRIVAL required a 3.5° descent profile after passing the SHEED waypoint for visual approach to runway 34 at Melbourne, increasing the risk of an unstable approach.

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included the:

- captain and first officer

- operator

- air traffic controller.

References

Manual of Air Traffic Services.

Flight Safety Foundation Approach and Landing Accident Reduction Tool Kit.

United States Aeronautical Information Publication.

ICAO Doc 4444 Procedures for Air Navigation Services, Air Traffic Management.

US Code of Federal Regulations Part 117 FLIGHT AND DUTY LIMITATIONS AND REST REQUIREMENTS: FLIGHTCREW MEMBERS.

Submissions

Under Part 4, Division 2 (Investigation Reports), Section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 (the Act), the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. Section 26 (1) (a) of the Act allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the captain, first officer, the international operator, the Australian operator, Airservices Australia and the Civil Aviation Safety Authority.

Submissions were received from Airservices Australia and the Civil Aviation Safety Authority. The submissions were reviewed and where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2015

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |