On 14 April 2005, an Aero Commander 500-S aircraft, registered VH-YJR, departed Brisbane aerodrome on a non-scheduled flight to Maryborough, Qld. It passed within 1 NM horizontally and 500 ft vertically of a Boeing Company 737-76Q (737) aircraft, registered VH-VBU, that was inbound from Darwin, NT, on a scheduled passenger service.

Sequence of events

On 14 April 2005, an Aero Commander 500-S aircraft, registered VH-YJR, departed Brisbane aerodrome on a non-scheduled flight to Maryborough, Qld. It passed within 1 NM horizontally and 500 ft vertically of a Boeing Company 737-76Q (737) aircraft, registered VH-VBU, that was inbound from Darwin, NT, on a scheduled passenger service.

The Aero Commander became airborne off runway 32 at 0543 Eastern Standard Time, 4 minutes after the nominated first light for Brisbane aerodrome. The Brisbane aerodrome controller had instructed the pilot of the Aero Commander to turn right, once airborne, onto a heading of 090 degrees and to climb to 2,000 ft. The pilot complied with the departure instructions and contacted the approach controller on the approach frequency. The approach controller acknowledged that broadcast and asked the pilot for 'good forward speed'.

The crew of the 737 were on the approach frequency and were positioning the aircraft for final approach to runway 19. Although the pilot of the Aero Commander and the crew of the 737 were on the approach frequency, the aerodrome controller confirmed with the approach controller that he was visually separating both aircraft as had been previously agreed. The aerodrome controller later reported that he was expecting the approach controller to assign a heading of 360 degrees to the pilot of the Aero Commander.

The approach controller passed traffic information to the pilots of both aircraft and the Aero Commander pilot sighted the 737 soon after. At 0544:20 the crew of the 737 reported that they were established on the final approach path for runway 19. The approach controller advised them that the Aero Commander was going to cross the runway 19 final approach path and that the tower was providing visual separation.

The aerodrome controller became concerned about the separation between the two aircraft and at 0544:50 asked the approach controller to instruct the pilot of the Aero Commander to turn left 20 degrees. That instruction was passed and the Aero Commander pilot complied. The aerodrome controller was still concerned and asked the approach controller to instruct the pilot of the Aero Commander to make an immediate hard left turn onto a heading of 360 degrees. The approach controller advised the aerodrome controller that he was concerned about that heading and did not transmit the instruction.

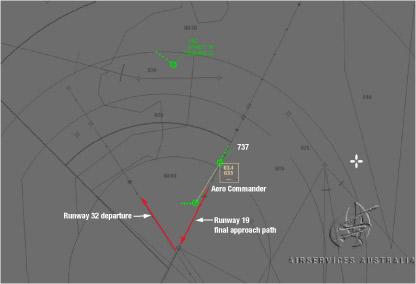

By 0545:26 the aerodrome controller considered that the Aero Commander had crossed the runway 19 final approach path. In response to a request by the approach controller, the pilot of the Aero Commander confirmed that he could see the 737, but at that stage the 737 crew had not seen the Aero Commander. Not long after that, the 737 crew saw the Aero Commander and were subsequently transferred to the Brisbane tower frequency. Figure 1 shows the position of the two aircraft as the Aero Commander crossed the final approach path at 0545:30.

Figure 1: Relative flight paths of the Aero Commander and the 737 as the Aero Commander crossed the final approach path of runway 19 at 05:45:30

A review of the recorded radar data showed that separation between the aircraft reduced to a minimum of 0.95 NM horizontally, at which time vertical separation had reduced to 500 ft.

Noise abatement procedures

The noise abatement procedures applicable at Brisbane at the time of the occurrence specified that all aircraft departing runway 32 between 2200 and 0600 must be contained within a sector of airspace between 360 and 120 degrees, over water, until leaving 5,000 ft. A heading of 360 degrees for a departure from runway 32 would have complied with those requirements.

To comply with the noise abatement procedures, runway 19 was the nominated duty runway for arrivals, and runway 01 was the nominated duty runway for departures. Pilots were also advised, on the automatic terminal information service, to obtain approval from air traffic control prior to starting engines. The requirement for a start clearance in thesecircumstances was in accordance with the Manual of Air Traffic Services (MATS) and enabled any delays to be absorbed on the ground before an aircraft's engines were started.

The aerodrome controller issued a start clearance to the pilot of the Aero Commander. The aerodrome controller did not coordinate the start clearance with the approach controller, nor was he required to do so. The ADC was required to review the disposition of inbound traffic when making a decision as to the timing of a start clearance.

The approach controller reported that he instructed the aerodrome controller to assign a departure heading of 090 to the pilot of the Aero Commander to ensure compliance with the noise abatement procedures.

Air traffic control separation standards and procedures

Control of aircraft in the Brisbane aerodrome terminal area was provided by an aerodrome controller located in the control tower using visual procedures, or by an approach controller using radar information. The MATS stated that the primary role of aerodrome controllers was to maintain visual observation of aircraft operations. Coordination of responsibilities and roles was required between the aerodrome controller and the approach controller, and formal guidelines were specified in a letter of agreement. The letter of agreement stated in part that:

In visual conditions, separation is achieved by the application of a radar standard or the provision of visual separation.

It also stated that:

In the application of visual separation, BNT [Brisbane aerodrome controller] shall ensure that separation in azimuth 1 is maintained until the establishment of a radar or procedural separation standard … In all situations where BNT is providing visual separation, traffic that will operate in close proximity will be retained on TWR [tower] frequency.

Although the aerodrome controller transferred the pilot of the Aero Commander to the departures frequency, the approach controller did not accept separation responsibility for the aircraft after the 737 was established on the runway 19 final approach path. He reported that he may not have been able to maintain the minimum radar separation standard of 3 NM horizontally, or 1,000 ft vertically.

The aerodrome controller reported that he accepted responsibility for visual separation between the two aircraft once the 737 was established on the runway 19 final approach path, because he had a 'mindset' that the Aero Commander was going to turn right onto a heading of 360 degrees once airborne. The aerodrome controller later reported that he would not have accepted responsibility for separation if he had realised that the approach controller had assigned a heading of 090 degrees, because that heading would not have enabled him to maintain visual separation between the two aircraft. Although the pilot of the Aero Commander advised the approach controller that he had the 737 in sight, the approach controller did not assign responsibility for separation to the pilot of the Aero Commander. There was an infringement of separation standards.

The information in the letter of agreement was supported by the Manual of Air Traffic Services (MATS), which contained procedures to be used by air traffic controllers. Paragraph 4.5.2.8 (effective 10 June 2004) stated that:

In providing visual separation, controllers should rely primarily on azimuth. Visual separation by judgement of relative distance or height shall be used only with such wide margins that there is no possibility of the aircraft being in close proximity.

The Brisbane tower was equipped with a radar display that provided the aerodrome controller with the same traffic display that was provided to the approach controller. The MATS addressed the use of tower radar in an aerodrome control service. It stated that the tower radar display was available for the determination of the altitude, position, or tracking of aircraft to establish or monitor separation. However, the MATS also stated that:

…the use of Tower radar should not impinge upon an aerodrome controller's primary function of maintaining a visual observation of operations on and in the vicinity of the aerodrome.

The MATS also stated that separation assurance could be achieved through planning traffic to ensure separation, executing the plan to achieve separation and monitoring the situation to ensure that the plan and the execution are effective.

Aerodrome controller

The aerodrome controller was trained and rated for the aerodrome control function at Brisbane. At the time of the occurrence he was nearing the end of a night shift which had commenced at 2200 the previous day. He reported that there had been a data upgrade to The Australian Advanced Air Traffic System during the night. The aerodrome controller considered that the data upgrade resulted in a higher workload than a standard night shift.

The aerodrome controller reported that, at the time of the occurrence, he felt fatigued. He also reported that he was feeling slightly unwell, but that he considered himself fit for duty. He was sleeping adequately and, apart from the slight illness, there were no indications of any personal, physiological or medical issues that were likely to have influenced the controller's performance.

Meteorological information

The weather information being broadcast to pilots for Brisbane Airport at the time of the occurrence advised that the visibility was greater than 10 km, that there were showers in the area and some cloud at 2,500 ft. The wind was reported as 180 degrees at 8 kts, with a maximum downwind of 10 kts on runway 01.

ANALYSIS

Introduction

Although there was no specified minimum distance standard for visual separation in these circumstances, the aerodrome controller was unable to continue to apply a visual separation standard, in azimuth, between the 737 and the Aero Commander. This analysis examines the development of the occurrence and highlights the safety issues that became evident as a result of the investigation.

Noise abatement procedures

Airspace restrictions imposed by the noise abatement procedures in force at the time of the occurrence resulted in limited options available to either the aerodrome controller or the approach controller to separate the departing Aero Commander with the inbound aircraft. The approach controller determined that he would be unable to establish and maintain a separation standard between the two aircraft and comply with noise abatement procedures, and so relied on the aerodrome controller to separate the two aircraft using visual separation.

The requirement for pilots to request a start clearance would normally provide the aerodrome controller with an opportunity to assess the traffic situation, in light of airspace limitations associated with noise abatement procedures, so that any delays can be absorbed prior to the aircraft's engines being started. A heading of 360 degrees was an appropriate heading in the circumstances. It would also have complied with noise abatement procedures and facilitated the application of visual separation in azimuth.

Controllers cannot be held responsible for delays to departing aircraft as a result of noise abatement procedures. Controllers are required to take such restrictions into account in their normal decision-making processes. The noise abatement procedures themselves were not considered to have contributed significantly to this occurrence.

Air traffic control separation standards and procedures

The converging tracks of the two aircraft precluded the aerodrome controller from ensuring that visual separation, in azimuth, was not infringed.

The low light conditions at that time of day and the cloud cover, may have made it difficult for the aerodrome controller to visually determine the departure track of the Aero Commander. Reference to the tower radar display was authorised by the Manual of Air Traffic Services (MATS) and would have clearly indicated the Aero Commander's track. Had the aerodrome controller referred to the tower radar display earlier, he may have been able to take action in sufficient time to ensure that separation was not infringed.

The situation which arose, where the aerodrome controller was separating the aircraft while the aircraft were not on the aerodrome control frequency, was not consistent with the letter of agreement. However, it did enable the approach controller to provide mutual traffic information to the pilots of both aircraft. That increased the awareness of the 737 crew of the presence of the Aero Commander and assisted the pilot of the Aero Commander to see the 737.

Although it would have been difficult for the aerodrome controller to separate the departing Aero Commander on a heading of 090 degrees, with arriving aircraft on the final approach path for runway 19, the aerodrome controller accepted those instructions and confirmed that he could separate in those circumstances. On that basis, the approach controller authorised the departure. The approach controller coordinated the departure instructions with the aerodrome controller in accordance with the letter of agreement. The approach controller confirmed, on a number of occasions, that the aerodrome controller had accepted responsibility for separating the Aero Commander on a heading of 090 degrees. The approach controller had no way of knowing that the aerodrome controller had misunderstood the instruction.

From the aerodrome controller's perspective, a heading of 360 degrees off runway 32 was appropriate given the disposition of the arriving aircraft. It would also have complied with the noise abatement procedures and enabled him to visually separate the Aero Commander in azimuth with the 737, once the 737 was established on the final approach path.

The aerodrome controller's subsequent request for a 20 degree left turn for the Aero Commander is difficult to reconcile. The resultant heading of 070 degrees turned the Aero Commander towards the 737 and does not appear to be consistent with a resolution of the developing confliction. By that time the aerodrome controller could not have been certain from visual observation that the aircraft were not in close proximity.

The investigation was unable to determine why the aerodrome controller had a 'mindset' that the Aero Commander was departing on a heading of 360 degrees, when that option was never discussed or coordinated with the approach controller. The higher workload that was reported to have resulted from The Australian Advanced Air Traffic System data upgrade may have had an adverse effect on the aerodrome controller's cognitive processes towards the end of the night shift. The possibility that fatigue contributed to the occurrence could not be discounted.

SAFETY ACTION

As a result of this occurrence, Airservices Australia proposed the following system improvements:

- Brisbane approach training packages to be revised to incorporate runway 14/32 scenarios in future training modules

- Examine options for including additional content on tower visual separation procedures into Brisbane approach training modules

- Routine performance assessments for Brisbane approach controllers to formally assess knowledge of reciprocal runway procedures.

At the time of writing this report, the Bureau had not received advice from Airservices Australia regarding the status of these proposals.

On 20 December 2005, Airservices Australia advised the ATSB of the following safety actions:

- Knowledge of reciprocal runway operations is tested during assessments.

- Tower controllers have completed familiarisation periods in approach.