On 31 January 2005, a de-Havilland Canada Dash 8-202 (Dash 8) aircraft that was inbound to Williamtown Airport, NSW, on a scheduled passenger service from Brisbane, Queensland, passed 0.6 NM laterally and 300 ft vertically by the second of two formations of two McDonnell Douglas Corporation F/A-18 (Hornet) aircraft that were inbound to Williamtown Airport after a training exercise. As the Dash 8 turned onto the base leg, the second formation was about 6 NM north-west of Williamtown Airport, at 2,900 ft above mean sea level. The pilots of the Dash 8 descended in response to a traffic alert and collision avoidance system resolution advisory (RA) they received on that formation. The approach controller did not provide the required separation standard of 1,000 ft vertically or 3 NM laterally between the Dash 8 and the second formation. The tower controller had not established a visual separation standard between the aircraft at the time the Dash 8 pilots received the RA. There was an infringement of separation standards.

The investigation found that the factors that contributed to the occurrence included:

- The approach controller did not assign an altitude to the second formation that provided a vertical separation standard between the second formation and the Dash 8

- The tower supervisor advised the tower controller to cancel an instruction to the Dash 8 pilots to orbit on the downwind leg of the circuit at 2,500 ft, and to continue on the downwind leg of the circuit

- The tower controller did not notify the approach controller that the Dash 8 was extending towards the lateral boundary of tower airspace

- The pilots of a Westwind incorrectly notified the tower that their aircraft was 'minimum fuel' and did not join the circuit via the upwind leg as instructed by the tower controller.

Sequence of Event1

On 31 January 2005, a de-Havilland Canada Dash 8-202 (Dash 8) aircraft that was inbound to Williamtown Airport, NSW, on a scheduled passenger service from Brisbane, Queensland, passed within 1 NM laterally and 300 ft vertically of the second of two formations of two McDonnell Douglas Corporation F/A-18 (Hornet) aircraft that were inbound to Williamtown Airport after a training exercise. As the Dash 8 turned onto the base leg, the second formation was about 6 NM north-west of Williamtown Airport, at 2,900 ft above mean sea level. The pilots of the Dash 8 descended in response to a traffic alert and collision avoidance system (TCAS) resolution advisory (RA) they received on that formation. The approach controller did not provide the required separation standard of 1,000 ft vertically or 3 NM laterally between the Dash 8 and the second formation. The tower controller2 had not established a visual separation standard between the aircraft at the time the Dash 8 pilots received the RA. There was an infringement of separation standards.

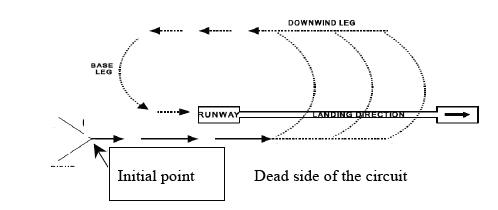

At about 1539:353,4 Eastern Daylight-saving Time, the pilots of an Israel Aircraft Industries Limited 1124A Westwind (Westwind) aircraft, that had been participating in a military training exercise, contacted the tower controller and advised that they were 7 NM to the north of Williamtown Airport, tracking to join the circuit on a left base leg for runway 12. At that time, the first formation of Hornet aircraft had passed the initial point5 (Figure 1) for runway 12, and the Dash 8 was in an early right downwind position.

At 1540:10, the tower controller advised the pilots of the Dash 8 to conduct orbits to the south-west of the airfield at 2,500 ft. However, the tower supervisor assessed that the Dash 8 could continue on the downwind leg and advised the tower controller to cancel the orbit instruction. At 1540:20, the tower controller complied and instructed the pilots of the Dash 8 to continue on the downwind leg. The tower supervisor had intended to position the Dash 8 behind the first formation in the landing sequence.

Figure 1: Generic depiction of a military stream landing circuit showing the location of the initial point (left circuit depicted)

(adapted from the Manual of Air Traffic Services Pt 3 s3, effective 10 June 2004)

At 1541:10, the tower controller instructed the pilots of the Dash 8 to make a visual approach and to track for right base. At 1541:20, the tower controller instructed the pilots of the Westwind to join the circuit via the upwind leg. In response to that instruction, the pilots of the Westwind advised the tower controller that the aircraft was 'minimum fuel'6. The tower controller did not respond immediately to that broadcast and the Westwind continued the approach via left base. At about 1541:30, the radar data showed that the Dash 8 had already commenced the turn onto the right base leg of the circuit. At that time, the Westwind was established on left base. The Westwind pilots had positioned their aircraft behind the first formation in the landing sequence. In order to separate the Dash 8 and the Westwind, the tower controller instructed the pilots of the Dash 8 to continue on the downwind leg and that they were now to follow the Westwind.

At 1542, the tower controller advised the pilots of the Dash 8 that they could turn onto the base leg, when ready. At that time the aircraft was close to the airspace boundary separating tower and approach areas of responsibility, about 6.9 NM north-west of the airport.

At 1542:20, the approach controller provided traffic information, on the Dash 8, to the pilots of the second formation. A review of the recorded radar data showed that, at that time, the second formation was about 3 NM behind the Dash 8. Although the investigation was unable to accurately determine the vertical distance between the aircraft, from that radar data, it appeared that there was about 100 ft between the second formation and the Dash 8 when the approach controller provided traffic information to the pilots of the second formation. The pilot of the lead aircraft in the second formation advised the approach controller that he could see the Dash 8.

The recorded radar data also showed that the altitude of the Dash 8 increased from 2,500 ft on late downwind, to 2,900 ft as the aircraft commenced the base turn, before descending in response to the TCAS RA. The Dash 8 subsequently continued to descend for a landing. At 1542:50, the second formation passed abeam the Dash 8, when the Dash 8 was about to commence the turn onto the final approach leg. At that time, there was 0.6 NM laterally between the aircraft, and the Dash 8 was 300 ft vertically below the second formation. The pilots of the Dash 8 advised the tower controller that they had received an RA and that they were on a 'TCAS descent'.

At 1543, the pilots of the second formation called the tower controller and advised that they were at the right initial7 position. The tower controller then realised that the second formation was inbound and provided the pilots of the Dash 8 with traffic information on that formation.

Minimum fuel

In accordance with the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Williamtown Standing Instructions, the Westwind was considered to be a military aircraft while participating in military exercises.

The copilot of the Westwind notified the tower controller that the aircraft was 'minimum fuel' when the aircraft was on a left base position for runway 12. The pilot in command of the Westwind later reported that the aircraft was not 'minimum fuel', and that the copilot had mistakenly made the 'minimum fuel' radio broadcast. The operator of the Westwind advised that the declaration of minimum fuel in that aircraft meant there was '…900 [pounds] or less total fuel remaining at the Base Turn Point when in the circuit, at an airport where a landing is assured'.

Air traffic control separation standards and procedures

Control of aircraft in the Williamtown Airport terminal area was provided by a tower controller using visual procedures and vertical separation, and by an approach controller using radar and procedural separation standards, in accordance with the Manual of Air Traffic Services8 (MATS) and local procedures. Coordination of control responsibilities was required between the approach controller and the tower controller in accordance with local procedures.

The required minimum vertical separation standard between the Dash 8 and other aircraft operating in the Williamtown airspace was 1,000 ft.

In relation to the provision of aircraft separation, the MATS 4.1.1.4 stated that:

Tactical Separation Assurance places greater emphasis on traffic planning and conflict avoidance rather than conflict resolution. This is achieved through:

- the proactive application of separation standards to avoid rather than resolve conflicts;

- planning traffic to guarantee rather than achieve separation;

- executing the plan so as to guarantee separation; and

- monitoring the situation to ensure that plan and execution are effective.

The tower controller cleared the pilot of the Dash 8 for further descent on a visual approach when the aircraft was in a late downwind position. A visual approach authorised the pilots to continue descent visually for a landing. A review of the recorded radar data showed that the Dash 8 maintained 2,600 ft for about 1.5 minutes on the downwind leg of the circuit. It reached a minimum altitude of 2,500 ft, on descent, when the aircraft was on a late downwind position, and climbed to 2,900 ft as it turned onto the base leg.

The Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP) advised pilots that they must report to ATC 'when the aircraft has left a level at which level flight has been conducted in the course of climb, cruise or descent'. The pilot in command of the Dash 8 did not recall climbing the aircraft from 2,500 ft on the downwind leg to 2,900 ft on the base leg of the circuit.

Approach control

At Williamtown Airport, the approach controller was responsible for providing an air traffic control service between instrument flight rules (IFR) category aircraft in accordance with the MATS and local procedures. That included ensuring that a separation standard existed between arriving IFR aircraft, and providing an orderly flow of arriving aircraft.

There was an approach controller and a supervisor rostered in the Williamtown approach control unit at the time of the occurrence. Both positions were staffed by an appropriately rated military air traffic controller (ATC). The approach controller had about 6 years experience as an ATC, and had been rated in the approach radar position at Williamtown Airport for 6 months. The approach supervisor was responsible for the supervision of the approach control unit at Williamtown Airport. He had considerable experience as an ATC, and had held a rating in approach control at Williamtown Airport for about 18 months.

A review of the recorded radar data showed that, at the time the approach controller cleared the pilots of the second formation to descend to 3,000 ft, the second formation was approximately 27 NM from the airport, with about 32 NM to fly to land. Had the pilots of the Dash 8 not been instructed to extend the downwind leg, the Dash 8 would have had about 6 to 8 NM to fly to touch down. The assignment of 3,000 ft to the pilots of the second formation did not provide either a vertical separation standard, or separation assurance, between the second formation and the Dash 8 in the circuit. The approach controller was not concerned about the separation between the Dash 8 on the downwind leg, and the second formation on descent to 3,000 ft, because of the distance the second formation was from the airfield at the time the approach controller issued the descent clearance.

The normal circuit direction at Williamtown Airport, on runway 12, was right. Military aircraft would track from the initial point along the dead side9 of the circuit and turn right, into the circuit, once the pilot saw the other traffic operating in the circuit (see Figure 1). The approach controller cleared the Westwind to enter the circuit via a non-standard left base leg and to descend on a visual approach.

The tower controller was required, by local procedures, to advise the approach controller when the Dash 8 pilots were cleared to descend on a visual approach.

On receipt of that advice, the approach controller removed the Dash 8's flight progress strip10 from the flight progress board11. Although the aircraft was still visible to the approach controller on the situation data display (SDD)12, the potential for an infringement of separation standards was no longer presented to the approach controller on the flight progress board. The approach controller later reported that the flight progress strip was removed from the board because there was an expectation that the second formation would remain clear of the Dash 8 in the circuit.

Tower control

The tower cabin was equipped with an SDD that provided the tower controller with the same display of air traffic that was provided to the approach controller. The MATS addressed the use of tower radar in an aerodrome control service. It stated that the tower radar display was available for the determination of the altitude, position or tracking of an aircraft to establish or monitor separation. However, the MATS also stated that:

…the use of the tower radar should not impinge upon an aerodrome controller's primary function of maintaining a visual observation of operations on and in the vicinity of the aerodrome.

There were three operational control positions established in the control tower; a supervisor position, a tower control position and a surface movement control position. Each position was staffed by an appropriately rated military ATC. The supervisor and the tower controller each had 18 months tower control experience. The control tower was also a training environment at the time of the occurrence. There was a controller-under-training in each of the three control positions. Each rated military controller, in each of the positions, was also a qualified training officer.

The supervisor was responsible for airspace management and operations on the airport. The supervisor had the authority to assess and amend the decisions of the tower controller and the surface movement controller if required. Unless the tower controller considered that such intervention compromised safety, the tower controller was obliged to comply with the decisions of the supervisor.

The first formation joined the circuit on a right crosswind leg on descent from 1,500 ft. Once the tower controller was able to apply a visual separation standard between the Dash 8 and that formation, the tower controller instructed the pilots of the Dash 8 to descend on a visual approach.

The tower controller was also required to notify the approach controller of any aircraft that were extending towards the aerodrome traffic zone (ATZ) lateral boundary which was the lateral boundary of tower airspace13. Neither the tower controller nor the supervisor advised the approach controller that the Dash 8 was extending downwind, and would be turning onto the base leg in the vicinity of the lateral boundary of the ATZ. The approach controller was not expecting to see the Dash 8 in that position. The approach controller observed, on the SDD, the Dash 8 turning onto the base leg of the circuit in the vicinity of the lateral boundary of the ATZ, and in the vicinity of the second formation.

The approach controller immediately provided traffic information to the pilots of the second formation about the Dash 8, but could not provide traffic information to the Dash 8 pilots as they were operating on the tower frequency.

The tower controller later reported that he originally intended to instruct the pilots of the Dash 8 to remain in the downwind position at 2,500 ft because it enabled him to better regulate the circuit traffic, especially given that he was instructing a controller-under-training at the time.

Instructing pilots to maintain 2,500 ft on the downwind leg was a common practice at Williamtown Airport. The AIP En Route Supplement Australia (ERSA) advised that all civil aircraft operating at Williamtown Airport were required to carry 30 minutes holding fuel. The tower controller later reported that that holding fuel enabled Williamtown air traffic control the flexibility to hold civil aircraft for up to 30 minutes, if necessary, for sequencing with arriving military aircraft.

Australian Defence Air Traffic System (ADATS)

Air traffic controllers at Williamtown Airport used the Australian Defence Air Traffic System (ADATS) to control aircraft operating within the Williamtown airspace. The ADATS associated a flight plan to an allocated transponder code14 and displayed that information to the controller as a data block, attached to the aircraft track symbol, on the SDD.

The data block could either be a full or limited data block. The full data block was white and included the call sign, altitude and radar derived ground speed, of airborne aircraft equipped with a serviceable transponder. It could also include other control information entered by a controller. A code and flight plan remained associated for a predetermined period of time depending on the nature of the flight. Once that time expired, the code/flight plan association terminated and the data block presented to the controller became a limited data block. The limited data block format did not display the call sign, and the colour of the data block changed from white to green. The limited data block format displayed an aircraft's allocated transponder code, altitude and radar derived ground speed.

The colours allocated to the track symbol and data block indicated the relevance of that aircraft to controllers. A green data block normally indicated that the aircraft was no longer of concern to the controller, as the flight plan was no longer active. The data block and track symbol colours assisted controllers with situational awareness.

The information displayed to the approach controller was also displayed to the tower controllers on the tower SDD. All information on relevant inbound, locally-based, military aircraft was displayed in the aircraft data block, including sequencing and tracking information. In accordance with local procedures, while a flight plan was associated with a specific transponder code, there was no requirement for the approach controller to provide voice coordination to the tower controller.

That applied to locally-based, military aircraft, as that information was available on the tower SDD. The tower controller was required to scan the SDD to determine the sequence and tracking details of arriving locally-based military aircraft. Tower controllers relied on the accuracy of the information presented in the data block, including the colour and sequencing instructions, to assist them in determining an estimated time of arrival, the arrival sequence and the inbound route of each aircraft.

Controllers reported that occasionally the code/flight plan association terminated while aircraft were still airborne. In those circumstances, in accordance with local procedures, the approach controller was required to use voice coordination to advise the tower controller about relevant inbound aircraft. The tower controller would not necessarily detect an inbound aircraft on the SDD if the code/flight plan association had terminated, unless voice coordination was received from the approach controller.

The code/flight plan association for the second formation terminated as the formation tracked to the circuit area and the data label changed colour from white to green. The approach controller reported that, as the termination occurred close to the circuit area, the tower controller would already have been aware that the formation was inbound. As a result, no voice coordination was provided to the tower controller.

Meteorological information

The weather was reported as fine and clear and was not considered to have been a factor in the occurrence.

- Only those investigation areas identified by the headings and subheadings were considered to be relevant to the circumstances of the occurrence.

- A tower controller employed by the Department of Defence provides a similar air traffic control service as a civil aerodrome controller.

- The 24-hour clock is used in this report to describe the local time of day, Eastern Daylight-saving Time, as particular events occurred. Eastern Daylight-saving Time was Coordinated Universal Time (UTC)+ 11 hours.

- Due to the limitations with the audio recording, all times are accurate to within about +/- 5 seconds.

- The initial point for runway 12 at Williamtown Airport was located about 4 NM from the threshold of runway 12 along the extended centreline of taxiway Alpha, at 1,500 feet above mean sea level.

- This phrase is used to advise air traffic control that the pilot requires priority for landing based on the amount of fuel remaining, calculated at a particular stage of flight (Manual of Air Traffic Services, pt 10, effective 9 June 2004).

- The left, right and straight initial positions are 30 seconds prior to the initial point with wings level.

- The Manual of Air Traffic Service is a joint civil/military publication used by Department of Defence and Airservices Australia air traffic controllers.

- The dead side of the circuit is the side of the airfield or active runway, opposite to that of the circuit pattern in use, and from which arriving aircraft joining the circuit.

- A flight progress strip is a thin cardboard strip used to record flight data relating to control of an aircraft.

- A flight progress board is a piece of equipment used to display flight progress strips. Controllers use the information on the flight progress board to assist in managing the traffic situation.

- The situation data display was an electronic display of radar derived information that depicted the positions and movements of aircraft.

- The ATZ is that airspace within 5 NM of the tactical air navigation equipment ground based navigation aid, over land, from ground level to 1,500 ft above mean sea level. At Williamtown Airport, the stream landing circuit pattern (see Figure 1) is contained entirely within the ATZ.

- A transponder is a receiver/transmitter which will generate a reply signal upon proper interrogation, in this case, of a signal generated by a ground based transmitter/receiver.

ANALYSIS

Introduction

The tower controller and the approach controller were unable to continue to apply a separation standard between the second formation of Hornets and the Dash 8. This analysis examines the development of the occurrence and highlights the safety issues that became evident as a result of the investigation.

Air traffic control separation standards and procedures

The approach controller's assignment of 3,000 ft to the pilots of second formation of Hornets when they had about 32 NM to fly to land, did not provide either a vertical separation standard or separation assurance between the second formation and the Dash 8. That action precipitated the sequence of events that followed. While a radar separation standard existed initially between the Dash 8 and the second formation, it relied on continuous monitoring by the approach controller. The allocation, by the approach controller, of an altitude to the second formation that would have provided the 1,000 ft vertical separation standard with the Dash 8 would have assured that a separation standard continued to exist. It would also have given the tower controller the option to assign further descent to the pilots of the second formation once a visual separation standard between the second formation and other aircraft joining the circuit could be applied.

The approach controller was required to establish a separation standard between the second formation and the Dash 8, and to have that standard in place before transferring the responsibility for separation to the tower controller. In not providing separation assurance between the second formation and the Dash 8, the approach controller did not demonstrate 'the proactive application of separation standards to avoid rather than resolve conflicts' as stated in the Manual of Air Traffic Services (MATS).

It was likely that the limited data block format displayed on the second formation adversely affected the situational awareness of both the tower controller and the tower supervisor at the time the tower controller advised the pilots of the Dash 8 that they could turn base 'when ready'. The tower controller did not provide traffic information about the location of the second formation to the pilots of the Dash 8 until after the pilots of the Dash 8 advised that they were on a traffic alert and collision avoidance system descent. At the time the tower controller instructed the pilots of the Dash 8 to turn base the second time, the relative locations of the second formation and the Dash 8 placed the aircraft in potential conflict. That would have been apparent to both the tower controller and the tower supervisor had either of them been aware of the location and intentions of the second formation at that time.

The traffic situation in the circuit area became quite complex in a very short period of time. The relative inexperience of the tower controllers may have limited their ability to realise the potential for a relatively simple inbound sequence to develop into an infringement of separation standards.

Communication between the tower controller and the tower supervisor may have been difficult due to the complexity of communication between trainees and their training officers, and between controllers in the various control positions in the tower. Had the Dash 8 remained at 2,500 ft conducting orbits in the downwind position as initially instructed until the tower controller could fit that aircraft into the landing sequence, there may have been more time for the tower controller to:

- liaise with the tower supervisor

- regulate the flow of traffic

- identify the second formation on the situation data display (SDD)

- assess options that may have ensured that separation continued to exist

- evaluate the impact of the late declaration of 'minimum fuel' by the pilots of the Westwind

- provide traffic information where appropriate

- issue alternative instructions.

Once the tower controller notified the approach controller that the Dash 8 had been assigned a visual approach, the approach controller removed the flight progress strip from the flight progress board. After that, there was nothing to prompt the approach controller to critically re-evaluate the information on which the original evaluation, that the aircraft would not come into close proximity, was made, even though there remained a possible confliction between the inbound second formation and the Dash 8.

Although the decision by the tower supervisor to instruct the pilots of the Dash 8 to continue on the downwind leg of the circuit and not conduct the left orbit in the downwind position may have been appropriate, it unnecessarily increased the complexity of the traffic scenario, especially given the training workload in the tower at that time. It also reduced the options available to the tower controller once the Westwind joined the circuit on the left base leg rather than via the initial point, or the upwind leg of the circuit as instructed. The instruction issued to the pilots of the Westwind by the tower controller to enter the circuit via the upwind leg would have provided the Westwind with adequate priority and would not have compromised the safety of the flight. That may also have created an opportunity for the tower controller to locate the second formation on the SDD and therefore reduce the likelihood of an infringement of separation standards.

Tower supervisors have the authority to become involved with tactical air traffic control decisions and may assume control responsibility for sequencing or separation, without formally taking over from the tower controller. Tower supervisors must consider how an instruction to the tower controller might affect the situational awareness of that controller. A supervisor must be prepared to take control of the situation, in which they have intervened at a tactical level, until the tower controller can resume responsibility for separation. Otherwise tower controllers may inherit a scenario from the tower supervisor that they may not entirely understand, with little time to react.

Although the extended downwind of the Dash 8 resulted from the Westwind not complying with a control instruction, the tower controller was required to notify the approach controller that the aircraft was extending and may track beyond the lateral boundary of the Aerodrome Traffic Zone (ATZ). The tower controller did not notify the approach controller that the Dash 8 was extending downwind. Therefore, the approach controller was unaware that the Dash 8 was tracking towards the right initial point, in potential conflict with the second formation.

Minimum Fuel

Military air traffic controllers are familiar with pilots declaring 'minimum fuel' and with their responses in such circumstances. However, the disposition of the Westwind relative to base and final, the relatively complex nature of the traffic pattern at the time of the broadcast, and the training environment that existed in the control tower at the time of the occurrence, all reduced the time available for the controller to consider the impact of the 'minimum fuel' broadcast on the traffic pattern.

By the time the tower controller had an opportunity to assess the impact that that transmission may have on the landing sequence, and to determine what priority could have been provided to the pilots of the Westwind, the Westwind was already on the final approach leg. The pilots of the Westwind did not comply with the instruction by the tower controller to join the circuit on the upwind leg, even though that would have been acceptable in such circumstances. The declaration of 'minimum fuel' in such close proximity to the landing threshold may have distracted the controllers in the tower and reduced the effectiveness of their scans of the tower environment, including the SDD, and added to the complexity of the situation.

Australian Defence Air Traffic System (ADATS)

The approach controller did not provide the tower controller with information on the second formation after the code/flight plan association for that formation terminated. Although the approach controller reported that the termination occurred close to the boundary of tower airspace, the tower controller appeared to be unaware of the proximity of the second formation. Had the approach controller provided the tower controller with coordination on the second formation, in accordance with local procedures, the tower controller's attention would have been drawn to the location of that formation on the SDD. That may have given the tower controller an opportunity to ensure that the Dash 8 remained clear of the inbound path of the second formation.

CONCLUSIONS

Significant factors

- The approach controller did not assign an altitude to the second formation that provided a vertical separation standard between the second formation and the Dash 8.

- The tower supervisor advised the tower controller to cancel the instruction to the Dash 8 pilots to orbit on the downwind leg of the circuit at 2,500 ft, and to continue on the downwind leg of the circuit.

- The tower controller was not aware that the second formation was inbound to the circuit.

- The tower controller did not notify the approach controller that the Dash 8 was extending towards the lateral boundary of the ATZ.

- The pilots of the Westwind did not join the circuit via the upwind leg as instructed by the tower controller.

Contributing factors

- The code/flight plan association on the ADATS data block of the second formation terminated.

- The approach controller removed the second formation's flight progress strip from the flight progress board.

- The approach controller did not provide the tower controller with voice coordination on the second formation once the code/flight plan association terminated.

- The pilots of the Westwind incorrectly notified the tower controller that their aircraft was 'minimum fuel' when the aircraft was on left base.

- The tower controller and the tower supervisor were relatively inexperienced, and each had responsibility for a controller-under-training.

SAFETY ACTION

Safety Advisory Notice 20060014

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau suggests that the Department of Defence distributes this report widely among controllers so that supervisors are aware that intervention in separation and sequencing at the tactical level has the potential to adversely affect the situational awareness of the controllers under their supervision. Further, they must be prepared to take control of a situation if necessary, until the controller is able to safely resume responsibility for separation.

Safety Advisory Notice 20060015

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau suggests that the Department of Defence ensures that controllers are aware of the importance of the separation assurance provisions of MATS 4.1.1.4.