|

Key points:

|

A near collision where a Piper PA-28 training aircraft turned in front of an ATR72 regional airliner, reducing separation between the two aircraft to about 110 metres horizontally and 75 feet vertically, illustrates the dangers of making assumptions and having incomplete situational awareness, an ATSB investigation highlights.

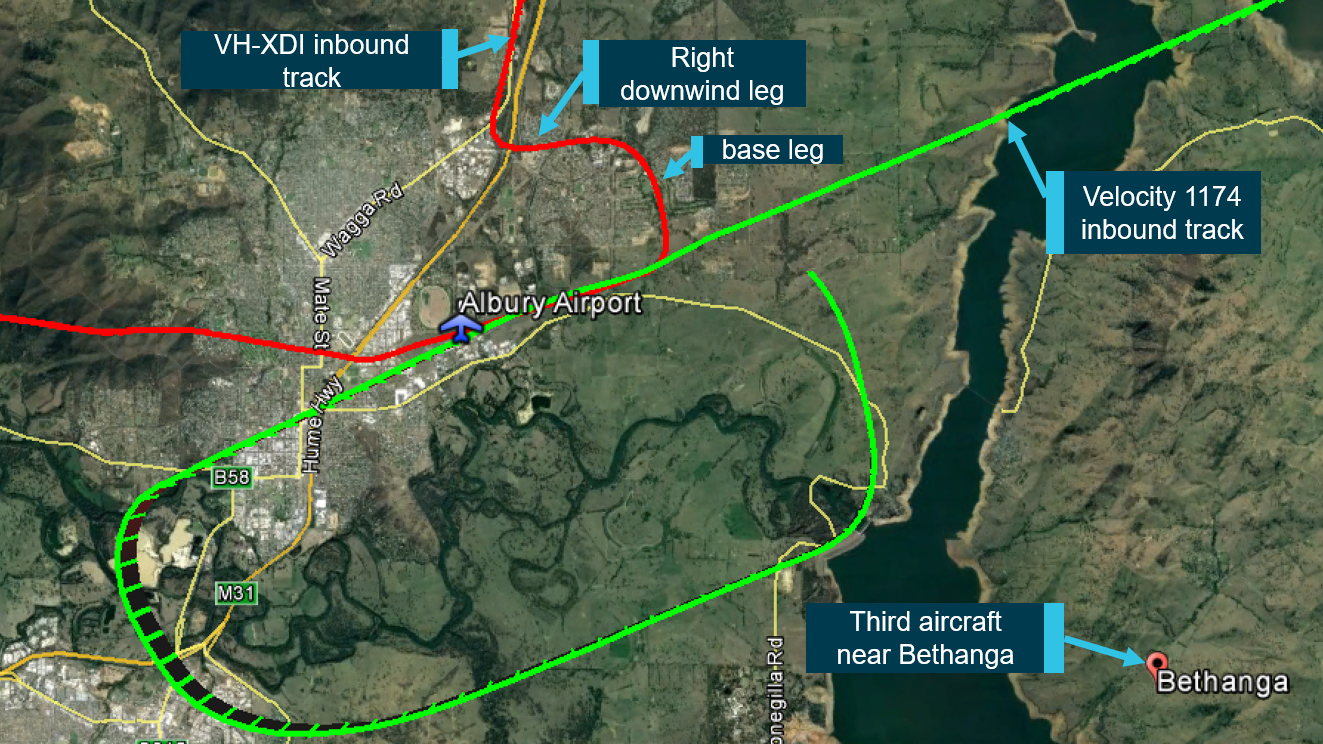

The Australian Airline Pilot Academy-operated PA-28, with a single student pilot on board, was conducting a navigation exercise to Albury from Wagga Wagga, NSW as part of the commercial pilot licence syllabus. On approach to Albury, air traffic control cleared the pilot to enter Albury (Class D*) airspace from the north. At the same time, a Virgin Australia Airlines ATR72 with two pilots, two cabin crew and 66 passengers on-board, was approaching Albury from the north-east, conducting a straight-in approach.

After the PA-28 had joined the downwind circuit leg for a touch-and-go landing on Albury’s runway 25, air traffic control informed the PA-28 pilot that ‘…you’re number two following an ATR on about a four‑mile final, report traffic in sight’.

The pilot acknowledged the instruction with the aircraft’s callsign, but did not read back any part of the instruction.

The controller later advised the ATSB that, due to their attention being focussed on a third aircraft, they were not monitoring the PA-28 as the aircraft continued on downwind and turned on to the base leg of the circuit. At that point the PA-28 pilot had not sighted the ATR nor advised the controller that they did not have it sighted.

Passing through approximately 600 feet above ground level, the ATR crew received a TCAS (traffic collision avoidance system) TA (traffic advisory) alert. They quickly identified the PA-28 below them and immediately commenced a missed approach.

The controller later reported not observing the near collision, and only shifted their attention back to the two aircraft when the ATR crew reported the missed approach. The controller advised that, as the ATR was already conducting a missed approach, they did not issue a safety alert.

The PA-28 pilot, meanwhile, advised the ATSB that when the ATR was first sighted it was so close that they lowered the nose of their aircraft to increase separation. The pilot recalled carrying out normal visual checks to ensure the base and final legs were clear, but did not look along the long final flightpath, assuming that the ATR, which had been cleared to land before the PA-28 joined downwind, was either on short final or had landed.

“As the PA-28 was operating under visual flight rules, separation between the two aircraft was the pilots’ responsibility, and the pilots on both aircraft made incorrect assumptions about both each other’s movements, rather than taking positive action to confirm that adequate separation would be maintained,” said ATSB Director Transport Safety Stuart Macleod.

“In addition, the air traffic controller had recognised the potential conflict and implemented a plan to sequence the aircraft’s arrival, however, the controller did not seek confirmation from the PA-28 pilot that they understood the instruction to follow the ATR.”

As well as finding that the PA-28 pilot did not sight the ATR, and did not advise the controller that they did not have the aircraft in sight before turning in front of the ATR, the ATSB’s investigation found the ATR flight crew were aware there was traffic in the area but did not assess the position of the PA-28 until the TCAS traffic advisory alert activated, Mr Macleod noted.

In addition, the investigation found that the controller did not identify the developing near collision as they were not effectively monitoring the aircraft in the circuit area due to their attention being focussed on another aircraft.

“The circumstances of this near collision incident illustrates the danger of assumption and incomplete situational awareness,” Mr Macleod said.

A number of safety actions have stemmed from the occurrence and the ATSB’s investigation, Mr Macleod noted.

“Virgin Australia and Airservices Australia have commenced discussions to convene a cross industry stakeholder meeting to include operators, the Civil Aviation Safety Authority, the ATSB and the broader industry to discuss the ongoing risk to operations at non‑controlled and Class D airports, such as Albury.”

Separately, AAPA conducted an internal investigation and implemented a number of additional risk controls, including the introduction of regular face-to-face seminars between controllers at Albury Tower and new students to explain operations in Class D airspace before students complete their first solo flight to Albury.

Read the report: Near collision between Piper PA-28, VH-XDI and ATR72, VH-FVR, Albury Airport, New South Wales, on 19 October 2019

* Apart from runway operations, there is no separation standard required between VFR and IFR aircraft operating in Class D airspace, but flight crew are required to follow the instructions provided by controllers. An instruction given by a controller is to prevent collisions, however, separation between aircraft is the responsibility of flight crew. While not applying separation standards, controllers use separation methods to ensure aircraft do not conflict. Additionally, traffic information should be passed in situations where the controller considers pilots may be uncertain of the intentions of a second aircraft.