Executive summary

What happened

On 6 October 2022, the pilot of a Bell 206B JetRanger helicopter, registered VH-PHP, departed Casino Airport, New South Wales for a solo ferry flight to Warnervale. The helicopter flew about 30–60 km inland of the coast before entering the inland visual flight rules route through the Williamtown military restricted area. Before exiting the restricted area, recorded flight data showed that the helicopter deviated from the pilot’s intended track. The helicopter turned around, deviated outside the lane, and the pilot did not respond to radio calls from Brisbane air traffic control.

The pilot then flew south and exited the restricted area below 500 ft above ground level. The helicopter was then observed by multiple witnesses to be heading towards the Hunter River, descending slightly, and was possibly initiating a turn when the helicopter rolled markedly and descended rapidly, colliding with the riverbank. The helicopter was destroyed, and the pilot was fatally injured.

What the ATSB found

Having discounted a number of other scenarios to explain the accident, the ATSB found that it was likely the pilot experienced an incapacitating event.

Less than 12 months prior, the pilot had undergone a review by a cardiologist that determined the pilot had minor coronary artery disease and was at a low to intermediate risk of a cardiac event. However, the pilot’s post-mortem showed they had severe coronary atherosclerosis within all 3 major coronary arteries with at least 80% blockage observed within each artery. While it was not possible to forensically determine if the pilot experienced a heart attack prior to the accident, it remained a significant risk factor for the pilot.

It was also established that the pilot did not declare a significant surgery and was taking numerous prescribed, non-prescribed, and recreational drugs, which had the potential to adversely affect their performance. Further, these were not declared to the Civil Aviation Safety Authority during their aviation medical examination, which prevented a specialist assessment of the aeromedical significance of the surgical outcome, nor the medication’s use and the underlying conditions for which they were prescribed.

Safety message

It is a pilot’s responsibility to declare a full medical history and medication use at the time of an aviation medical examination so that the Civil Aviation Safety Authority and the designated aviation medical examiner can assess a pilot and their medications’ suitability for flying. Alternate medication may be available if current medications for existing conditions are incompatible with flying, thereby permitting the pilot to manage both their own personal risks as well as those to aviation safety.

Pilots should also remain cognisant of health and lifestyle changes and how this may affect their fitness to fly. Do not fly if feeling unwell or until fully recovered from temporary medical conditions and manage chronic conditions in association with your designated aviation medical examiner.

The investigation

| Decisions regarding the scope of an investigation are based on many factors, including the level of safety benefit likely to be obtained from an investigation and the associated resources required. For this occurrence, a limited-scope investigation was conducted in order to produce a short investigation report, and allow for greater industry awareness of findings that affect safety and potential learning opportunities. |

The occurrence

On 6 October 2022, at about 1350 local time, the pilot of a Bell 206B JetRanger helicopter, registered VH-PHP, departed Casino Airport, New South Wales for a ferry flight to Warnervale. The helicopter was being returned to the registered operator after a long-term repair to correct hail damage and exchange life-expired parts. The pilot was the only person onboard.

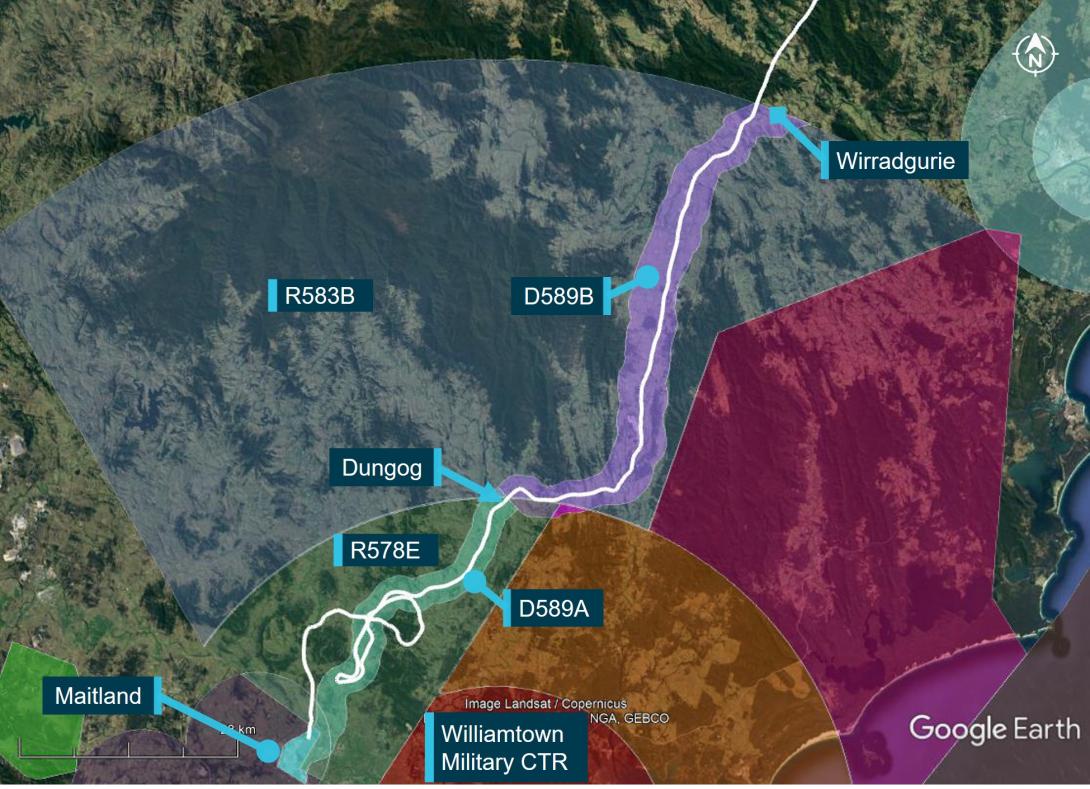

The helicopter tracked south-south-west, about 30–60 km inland of the coast (Figure 1).

Figure 1: VH-PHP flight track

Source: Google Earth and OzRunways, annotated by the ATSB

Recorded data indicated that at tracking point Wirradgurie, the pilot followed the inland visual flight rules (VFR)[1] route,[2] D589B and D589A (shaded in purple and green respectively on Figure 2), north of the Williamtown military control area (CTR) through restricted areas R583B and R578E.[3]

At about 1547, when approaching the township of Dungog, the pilot received a telephone call[4] from a family member enquiring as to their progress. The pilot reported the helicopter was flying well, operations were normal, and they were 5 minutes from Maitland and 20 minutes from Warnervale.

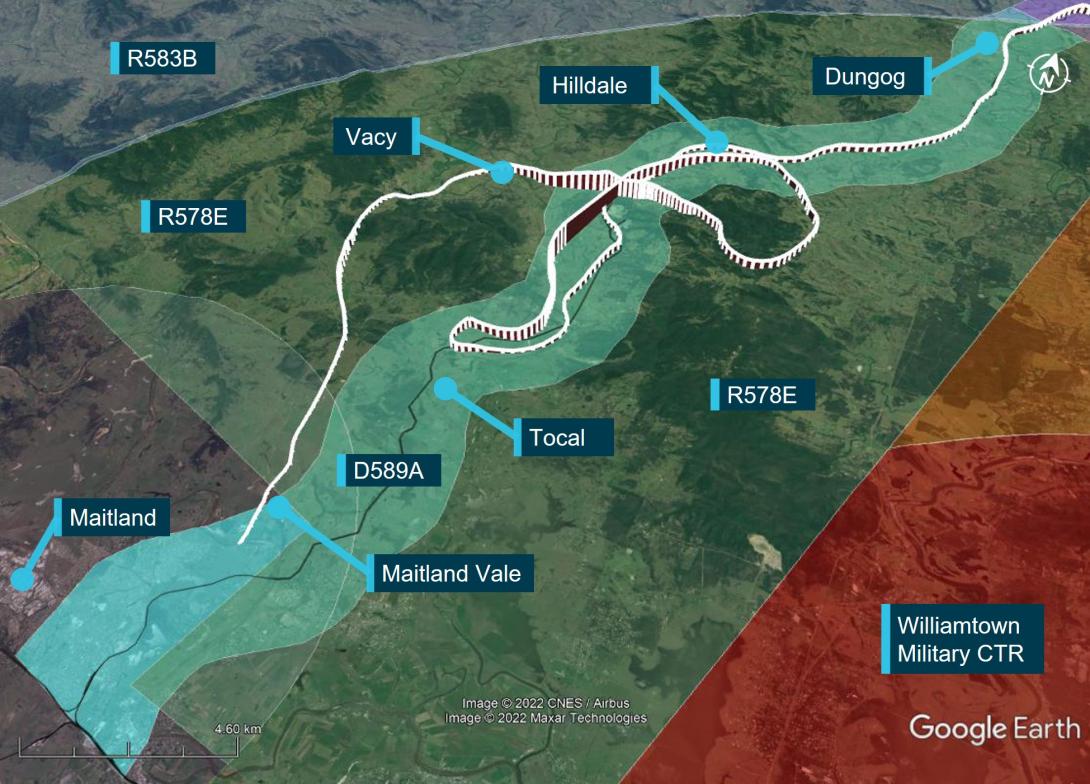

Figure 2: VH-PHP flight track (in white) through the Williamtown inland VFR route D589

Source: Google Earth and OzRunways, annotated by the ATSB

At about 1556, when approaching Tocal (Figure 3), about 4 NM (7 km) from the end of the lane, the helicopter started to climb and then conducted a right 180° turn to track northbound. After about 2 minutes, the helicopter transitioned through the upper limit of the VFR lane (1,600 ft) and continued climbing to 3,100 ft. The helicopter then descended to 1,100 ft, back into D589A and continued to follow the lane northbound until Hilldale when the pilot again made a right turn. This time the pilot flew the helicopter outside the lateral bounds of the lane by conducting a gradual climbing orbit around a hill before crossing from the east to the west of the lane, reaching 2,900 ft during the transition.

At about 1611, the helicopter then descended over the town of Vacy, flying as low as 120 ft above ground level and as slow as 22 kt ground speed before climbing and heading south. The helicopter then descended to low levels travelling parallel to, but just outside, the VFR lane western boundary until it exited the southern border of R578E at Maitland Vale.

Figure 3: VH-PHP flight track (in white) through the Williamtown VFR route D589A

Source: Google Earth and OzRunways, annotated by the ATSB

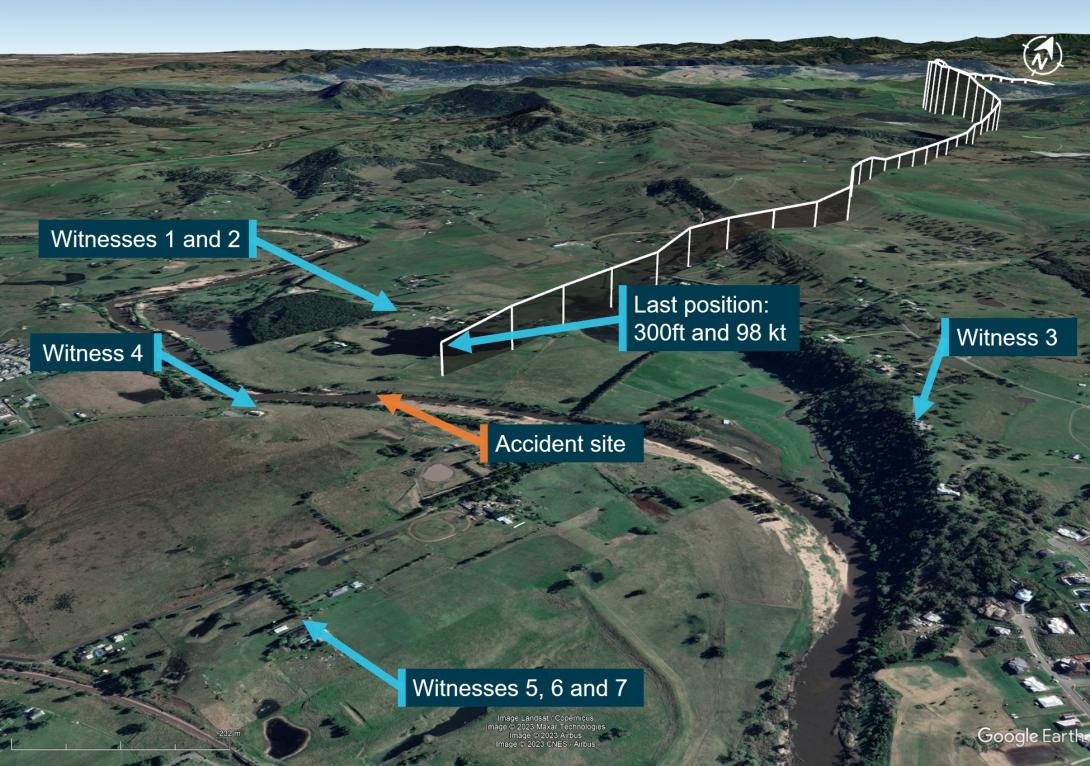

At about 1616, the helicopter cleared a ridge by about 200 ft and descended gradually toward the Hunter River. At the last recorded data position, the helicopter was at 300 ft and 98 kt (Figure 4).[5]

After clearing the ridge, the helicopter was visually observed by 7 witnesses. Common features of these reports were that the helicopter headed towards the river, descended slightly, possibly initiated a turn at which point it rolled markedly, descended rapidly, and collided with the riverbank. Some of those witnesses, as well as others who only heard the helicopter and the impact, reported the helicopter sounded normal or nothing out of the ordinary, while others reported it sounded rough or the engine was ‘screaming’.

The helicopter came to rest on a muddy river flat near the water’s edge. A first responder stated there was smoke coming from an engine fairing grille. They found a fire extinguisher in the cabin, discharged it into the grille and the smoke stopped. The helicopter was destroyed, and the pilot was fatally injured.

Figure 4: VH-PHP final flight track

Source: Google Earth and OzRunways, annotated by the ATSB

Context

Pilot information

The pilot held a Commercial Pilot Licence (Helicopter) and was qualified to fly by day under the visual flight rules (VFR). The pilot’s paper logbook indicated a total of 382.9 hours aeronautical experience, of which 132.5 hours were in various Bell 206 model helicopters. However, the last entry in this logbook was December 2003. No other paper or electronic logbooks could be found. The pilot indicated in their last aviation medical examination in October 2021 that they had 7,200 total flying hours and no hours recorded in the prior 12 months. Prior medical questionnaires recorded hours that appeared to be steadily increasing and rounded to the nearest 100 hours. The pilot had an OzRunways[6] account, which indicated they had accrued 27 hours since May 2017 while using their OzRunways application. The application recorded:

- 11.6 hours over 11 flights in 2017

- 1.0 hours over 2 flights in June 2018

- 11.9 hours over 17 flights in 2022.

In the 90 days prior to the accident, no flights were recorded by the application.

The pilot last conducted a single-engine helicopter flight review on 26 January 2022 that was valid until 31 January 2024. This flight was conducted in the accident helicopter. In interview, the flight instructor stated the pilot was ‘reasonably cautious, not overconfident’ and they were ‘not out of practice’.

The pilot held a Class 1 and Class 2 Aviation Medical Certificate issued by the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA). The Class 1 medical was valid until 26 October 2022 and the Class 2 valid until 26 October 2023. The pilot was required to have reading correction eyewear with them while flying.

The pilot had recently returned from an overseas holiday and had a head cold. A family member reported the pilot had 8 hours sleep the night before the flight and in the morning was in good spirits and appeared to have improved with respect to their head cold.

Helicopter information

VH-PHP was a Bell Helicopter Company, model 206A that was manufactured in 1970 in the United States. The helicopter was first registered in Australia in May 1986. In 1988, the helicopter was rebuilt and converted to a 206B model with fitment of a Rolls Royce/Allison 250-C20 turboshaft engine and the associated uprated transmission, rotor head and other required changes.

In 2019, the helicopter was damaged by hail and repaired over a 3-year period. During this time, other modifications were performed, including correcting issues associated with the A to B model conversion. In April 2022, as part of a maintenance test flight, the helicopter was flown from Warnervale to Casino. During the test flight, a ‘lazy’ power turbine governor was identified. Subsequently, further parts required repair or overhaul, including time-expired parts.

A 30 minute maintenance test flight associated with the replacement of components was conducted and the helicopter was found to be in a satisfactory condition. A maintenance release was issued, and the helicopter flew the following day with the aim of returning to Warnervale (the accident flight).

Meteorological information

In the days before the accident, the east coast of Australia had been under the influence of a low‑pressure system, which had included large quantities of rain in some areas.

The Bureau of Meteorology graphical area forecast, current for the accident flight, indicated greater than 10 km visibility and broken cloud[7] with a base of 4,000 ft above mean sea level on departure from Casino. However, shortly after taking off, the pilot was to fly into an area with isolated rain, 6,000 m visibility and scattered cloud with a 2,000 ft base. Further south along the flight path taken, the weather was forecast to have visibility greater than 10 km but reduced to 5,000 m and 2,000 m in scattered rain and showers. Broken cloud was forecast throughout these varied conditions.

At 1600, the aerodrome meteorological report (METAR)[8] for Maitland Airport (about 6 km west‑south-west from the accident site) recorded 8 kt of wind, visibility greater than 10 km, scattered cloud at 4,000 ft and 4,500 ft, and overcast cloud at 7,800 ft. The air temperature was 21 °C.

Two eyewitnesses separately reported seeing the helicopter, one as it operated down the D589A and the other when it was in the R578E restricted area. These witnesses reported the weather at the time to be a mid to high level overcast cloud with no rain. A retired airline pilot in the area of the accident site stated that the weather was suitable for VFR operations.[9] They observed a general base layer at 5,000 ft, and scattered cloud with patches to the south.

Recorded information

Position data

The helicopter had analogue instrumentation and had no fitted equipment that recorded data. The pilot was using the OzRunways application on their mobile phone. The application sent position information back to a server via a mobile data connection. Position, altitude, and ground speed was recorded for the entire accident flight at about 5 second intervals (refer to Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Radio communications

The Airservices Australia area frequency radio calls were reviewed. The pilot made no calls on the appropriate area frequencies for the flight, nor were they required to do so. At 1605, Brisbane Centre air traffic control made 3 calls trying to contact the pilot in response to the helicopter flying through restricted airspace R578E, with no response received.

No distress calls were made on the area frequency around the time of the accident.

Mobile phone

Mobile phone records showed that the pilot made and received multiple calls during the flight. Some calls were from family members checking on the pilot’s progress. At 1614, the pilot missed a call and received a missed call text. Also at 1614, the pilot received and answered a call from an unknown person for 27 seconds. The call ended about 60 seconds before the accident. Despite numerous attempts, the ATSB was unable to establish contact with this caller to seek any further information on the situation with the pilot at that time.

Wreckage and impact information

An initial assessment of the helicopter was conducted on the riverbank, however, due to rapidly rising river levels, the wreckage was moved to higher ground and the principal components were moved to a secure location for further examination.

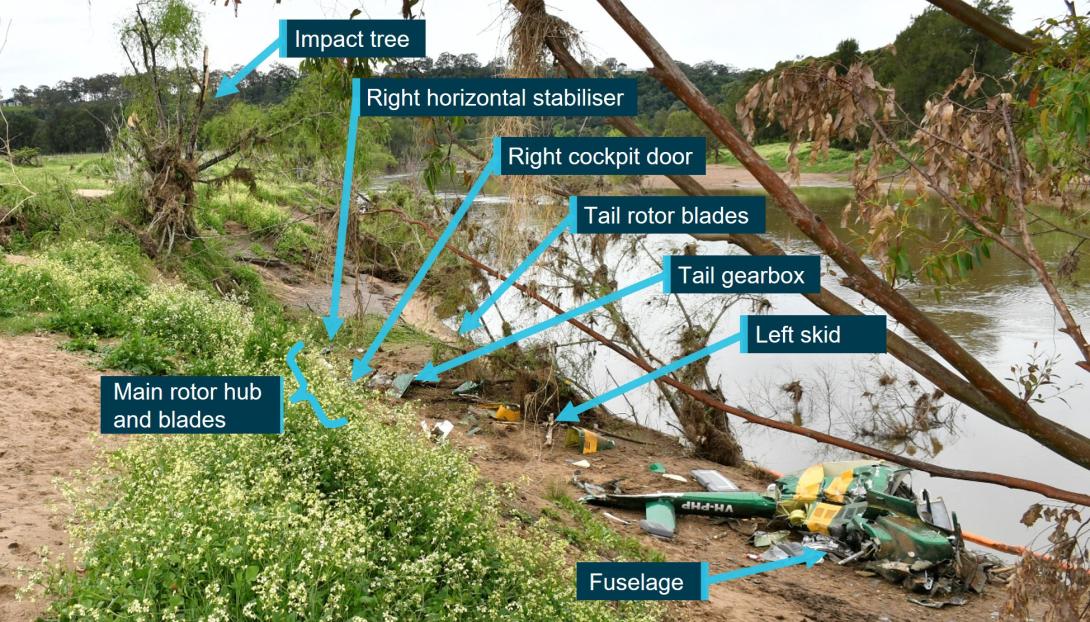

The wreckage trail was about 45° to the right of the last track direction recorded by the pilot’s OzRunways application (Figure 4). Examination of the accident site showed the wreckage trail (Figure 5) had started at a tree and extended along the riverbank for a distance of 33 m on a heading of 210° (magnetic). Figure 5 also shows the location of key components including the main rotor hub and blades, right horizontal stabiliser, right cockpit door, tail rotor blades, tail gearbox, left skid, and the fuselage.

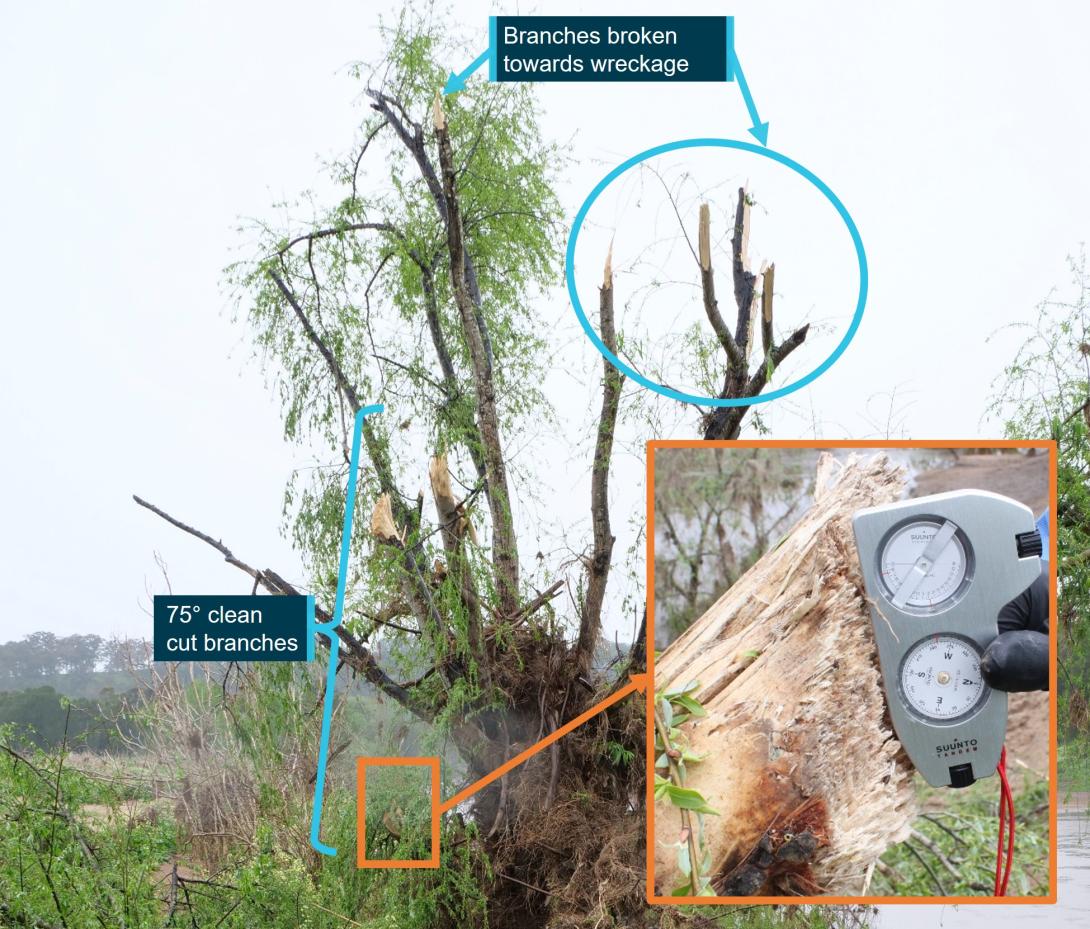

Some lower branches of the tree (Figure 6) were cut at 75° from the horizontal and the multiple cuts were at about 75° to each other suggesting they were cut by the main rotor system. Other branches higher up on the other side of the tree were snapped off in the general direction of the wreckage.

Figure 5: Wreckage trail

Source: NSW Police annotated by ATSB

Figure 6: Initial impact tree

Source: ATSB

All major aircraft components were accounted for at the accident site except for 2 parts of a main rotor blade. There was no evidence of a birdstrike identified in the wreckage.

The turbine and combustion sections of the engine had partially separated from the gearbox section. The left compressor discharge tube had separated from the compressor section at the compressor output flange. The right compressor tube was partially crushed between the combustion section and compressor section, consistent with the right side of the fuselage impact with terrain. The exhaust pipes were removed and a visual inspection of the output face of the power turbine was carried out with no defects evident. Due to the level of disruption to the engine and compressor casings, rotation of the power turbine and compressor was not possible.

The engine fuel and oil filters were removed and inspected with no unusual contamination found. The engine oil tank was punctured at the bottom of the tank by the tail rotor driveshaft. The puncture exhibited signs of rotation of the driveshaft and remnants of engine oil were found in the tank.

Fuel was found spilled at the accident site and fuel in the fuel filter bowl showed no evidence of contamination with water.

The main rotor hub was intact and attached to the mast section. The mast nut was installed and locked, and there were minimal signs of mast bumping.[10] Both main rotor blades were still attached to the rotor head.

The 2 parts unaccounted for were a 2 ft long outboard section of the main rotor blade leading edge and the associated blade tip weight. It was assessed that the leading edge and tip weight were likely projected into the swollen river during the impact sequence due to the helicopter heading, the pattern of damage, and fracture surfaces of the recovered adjacent leading edge, trailing edge and tip sections.

The main rotor mast was fractured near the main rotor head. The fracture surface was indicative of an overload failure. The main transmission was free and smooth in rotation. No oil was present due to the fracture of the oil filter mount, however, there was residual oil evident in the gearbox and the oil chip detector was removed and inspected with no signs of internal failure evident. The oil filter was opened and inspected with no signs of unusual contamination present.

The upper surface of the main rotor gearbox isolation mount had heavy scoring, caused by the rotating engine driveshaft during the impact sequence and the main gearbox input flange was radially scored through about 225° in a periodic saw-tooth pattern. This indicated that the engine was driving the driveshaft, and the main gearbox input flange were rotating at the time of separation.

In summary, examination of the helicopter’s flight controls, engine and structure did not identify any pre-existing defects that would have affected normal operation.

Survival aspects

The helicopter cabin underwent severe disruption upon impact with terrain. The front row seats were fitted with a 4-point harness. Evidence showed the pilot was wearing the safety harness correctly but due to the severity of the impact with the ground, the restraint system failed. The pilot was not wearing a helmet.

The accident was not considered survivable, and the pilot received non-survivable injuries.

Operational information

The pilot did not submit a flight plan, nor were they required to do so. The track taken was 30 to 60 km inland from the New South Wales coast, which allowed the pilot to fly under Class E and Coffs Harbour Class C controlled airspace.

At tracking point Wirradgurie, the pilot followed the inland VFR route west of Williamtown (Newcastle) Airport. The VFR route, designated in 2 segments as D589B and D589A, is a 2–3 NM (4–6 km) wide lane under restricted airspace from ground level to 2,500 ft above mean sea level and ground level to 1,600 ft respectively. The VFR lane enables pilots to visually fly under restricted areas R583B and R578E (military flying area) without requiring permission or monitoring by Williamtown airspace controllers.

The 2 eyewitnesses who observed the helicopter in D589A and R578E both reported that it appeared to be operating normally. There were other aircraft in the vicinity operating at higher altitudes both in R578E and in the Class G airspace just to the south of the restricted area. However, VH-PHP was the only aircraft broadcasting a transponder signal in the D589 inland VFR route at the time.

A family member who spoke with the pilot during the flight stated they were not aware of any reason why the pilot would have diverted from the intended track. Based on the assumed flight path and prior cruising ground speed, the estimated times given by the pilot of 5 minutes to Maitland and 20 minutes to Warnervale were broadly correct. However, when the subsequent deviation was included, the ATSB estimated the times to Maitland and Warnervale would have been closer to 29 minutes and 44 minutes respectively.

Medical and pathological information

Post-mortem examination

The forensic pathologist who conducted the post-mortem examination concluded that the pilot received fatal injuries sustained during the accident. However, they also noted severe triple vessel coronary artery disease with at least 80% lumen[11] stenosis[12] observed within each artery. The post-mortem report stated that:

Severe coronary artery disease is a risk factor for sudden death due to myocardial ischaemia[13] and subsequent fatal arrhythmia.[14]

However, the report also stated there were:

No features of acute myocardial infarction.[15]

Toxicological results from a post-mortem subclavian blood sample revealed the following medications, which were considered ‘non-fatal’ levels: alprazolam (<0.005 mg/L), diazepam (0.13mg/L), and metabolites nordiazepam, temazepam and oxazepam. Citing Baselt (2020), the forensic pathologist noted that:

Although alprazolam and diazepam were detected at non-lethal levels, they are both central nervous system (CNS) depressant medications which may act synergistically to cause sedation, confusion and incoordination.

Methylecgonine (0.13mg/L) a cocaine metabolite, Levamisole (a common cutting agent of cocaine) and cannabinoids (delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 0.006 mg/L and THC acid 0.004 mg/L) were also detected. Carbon monoxide saturation was less than 1% and no alcohol was detected.

Coronary artery disease

During the post-mortem examination, the pilot’s heart was found to have severe coronary atherosclerosis[16] within all 3 major coronary arteries (the left anterior descending coronary artery, circumflex artery and the right coronary artery) with at least 80% lumen stenosis observed within each artery. Histological examination confirmed the severe atherosclerosis within all 3 main coronary arteries, with 75-90% arterial lumen stenosis observed. Focal perivascular fibrosis[17] and occasional enlarged myocytes[18] were seen, which are both associated with the development of cardiac dysfunction.

In coronary artery disease, one or more of the coronary arteries are partially blocked by plaques. If a plaque breaks open, it can cause a blood clot in the heart, which can lead to a heart attack (also known as a myocardial infarction). They occur when the heart has either a sudden interruption of blood supply, or a longer term reduced blood supply, both of which cause damage to the heart muscle.

Signatures of a heart attack in survivors, such as heart inflammation and fibrosis (scarring) take time to develop and are not normally present in people who immediately succumb to the heart attack or an associated fatal event. Therefore, it may be challenging to identify a heart attack as the reason for an accident when sudden death occurs.

There are 3 types of heart attack. The most severe form is ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. It has the classic symptom of pain in the centre of the chest and may range from discomfort to debilitating. Other symptoms may include shortness of breath or trouble breathing, nausea, heart palpitations, anxiety, sweating, and feeling dizzy, lightheaded, or fainting.

The CASA fact sheet on coronary artery disease, noted that the disease is associated with distracting pain, acute shortness of breath, arrhythmia and sudden death. When considering the effect on flying, CASA indicated that ‘Stressful phases of flight can force the cardiac system to work harder. The sedentary nature of aviation can also be detrimental to this condition.’

The ATSB’s aviation medical specialist’s opinion was the pilot was at risk of a sudden incapacitating cardiac event. They had advanced triple-vessel coronary artery disease, capable of inducing incapacitating and distracting chest pain with or without an arrhythmia, such as ventricular tachycardia[19] or ventricular fibrillation.[20] This can induce severe and incapacitating chest pain leading to distraction and declining consciousness.

Medical history

The pilot had ongoing treatment for chronic insomnia with various medications being prescribed. They underwent a sleep study in 2016 and was found not to suffer from sleep apnoea. At the time of the accident, the pilot was prescribed 2 alternating medications for the insomnia: Alprazolam 2 mg and Amitriptyline hydrochloride 25 mg. Only Alprazolam was found in the pilot’s toxicology. The pilot had also previously been prescribed Stilnox for their insomnia.

The pilot also had a history of elevated blood pressure. Treatment had included medication although this stopped during a period of weight loss. The pilot had since regained weight but had not resumed treatment for high blood pressure.

In 2015, the pilot underwent spinal fusion surgery to correct pain associated with osteoarthritic degeneration of the lumbar spine. In 2020, the pilot underwent re-exploration surgery with the removal of existing intervertebral fusion cages and replacement with new ones. The family advised that this surgery was successful and greatly improved the pilot’s life.

Aviation medical examinations

The pilot had seen the same designated aviation medical examiner (DAME) for many years and medical examinations. In August 2018, the pilot failed a medical examination due to their diastolic blood pressure level.[21] The pilot reapplied for an aviation medical in May 2019 and passed the examination.

In October 2021, their Class 2 aviation medical certificate was due to expire and they attended a consultation with their DAME for a Class 1 and Class 2 medical examination. The pilot passed their examination based on the responses to the pre-medical questionnaire and the testing prescribed by CASA. These tests included an audiogram, a resting electrocardiogram, and a glucose and lipids blood test.

During a Class 1 medical examination, a DAME will enter updated information into the CASA medical record system, which calculates the risk score of an applicant using the CASA coronary heart disease risk factor prediction chart. The chart and an associated formula provide a cardiac risk index. Risk factors include age, high-density lipoprotein and total cholesterol levels, systolic blood pressure, and whether the person is a smoker, has diabetes or left ventricular hypertrophy.[22] A score above 14 triggers the requirement for further investigation starting with a stress electrocardiogram. During their most recent medical examination, the pilot did not score above 14.

The pilot declared in their questionnaire a lower back operation in 2015 and magnetic resonance imaging associated with that operation in 2016. The DAME assessed the pilot’s remaining range of motion to be adequate. In addition, they declared the sleep study undertaken in 2016. The pilot did not declare any ongoing medical issues, recent surgeries, nor that they had taken any prescribed medications in the last 4 years. The DAME had no other resources available to validate the pilot’s response that they were not taking prescription medications.

While the pilot passed their aviation medical exam, in discussions with the DAME, they decided the pilot should be referred for another sleep study and a cardiologist review. This was based on their current job stressors, history of weight fluctuations, history of high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and poor lipid control, and having been 5 years since their previous testing.

The pilot attended an appointment with a cardiologist in November 2021. The cardiologist reported that there was no evidence for significant heart disease and the pilot was at low risk of a significant cardiac event. As the pilot was unable to complete the stress electrocardiogram due to back pain, they were referred for a computed tomography (CT) coronary angiogram. The angiogram report stated a moderate burden of coronary artery calcification with plaques in all areas. In addition, it was reported that the pilot had only minor coronary artery disease (less than 25% narrowing), however, mixed plaque in the proximal third of the left anterior descending artery caused up to 25–49% narrowing. The report also stated the pilot had a poor calcium score of 340, which was in the ninetieth percentile for the pilot’s age and gender.

Civil Aviation Safety Authority requirements

A pilot is required to declare to CASA when they have a medically significant condition that affects them for a period of time and to stop acting as authorised by their licence while that condition continues. If the condition becomes chronic, the DAME, in consultation with CASA, may be able to treat the condition such that the pilot again meets the medical standard. CASA provides guidance for pilots on their website on the process and obligations.

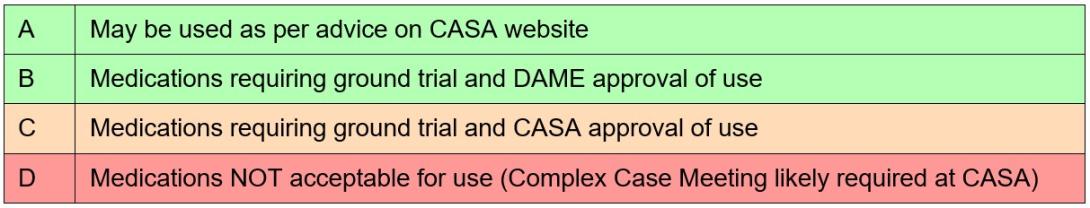

CASA lists the classes of medications that can have side effects, which may impair flying performance and groups them into 4 levels, categories A through D (Table 1).

Table 1: CASA medication categories

Category D broadly includes some conditions or classes of medications that can treat conditions such as, but not limited to, angina, cancer, Parkinson’s disease, hypertension, malaria, psychiatric conditions, seizures, smoking cessation aids, steroids and weight loss medications. It also includes Therapeutic Goods Administration Schedule 8 controlled substances.[23]

CASA advised the ATSB that alprazolam, amitriptyline hydrochloride and diazepam are classed as category D. They stated this was due to the side effects of the medications themselves or for the conditions in which they were treating. Alprazolam is a Schedule 8 controlled substance, while diazepam is a Schedule 4D restricted substance.[24] Stilnox is a category B medication, which was approved for use with the restriction of a short no fly period after ingestion.

CASA advised they can access the Medicare Benefits Schedule and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme to check an applicant’s history when it has reason to, such as when incomplete medical information is supplied by the applicant, for complex medical certifications, or for monitoring compliance with certain medications.

For the awareness of pilots, CASA publicises a limited list of approved medications, along with a list of medications that are considered hazardous or prohibited in aviation.[25] Medications that are considered as hazardous can only be used with the express clearance of CASA or a DAME.

Pharmacological influence

The post-mortem report was examined by a consultant forensic pharmacologist at the request of the ATSB. The review noted that the detection of THC and THC acid could have only occurred as a result of the use of cannabis. Specifically, the consultant concluded that, with the blood concentration[26] of diazepam and THC detected, some impairment of the high-level psychomotor skills required for flying would be expected and could not be excluded as being factors in the accident.

In 2012, the National Safety Council Committee on Alcohol and Other Drugs stated that it was unsafe to operate a vehicle or other complex equipment while under the influence of cannabis, its primary psychoactive component THC or synthetic cannabinoids with comparable cognitive and psychomotor effects. They reported that studies have demonstrated that cannabis intoxication produces dose-related impairment of cognitive and psychomotor functioning and risk-taking behaviour. They also reported the growing epidemiological evidence that detectable THC concentration in blood is associated with increased motor vehicle crash risk, particularly above THC concentrations of 0.002 mg/L.

The opinion of the forensic pharmacologist was the relative concentration of diazepam to the nordiazepam, oxazepam and temazepam concentrations in the pilot indicated they most likely used diazepam within 12 hours to 24 hours of the accident. The therapeutic range for diazepam is 0.1 to 2.0 mg/L.

Epidemiological and experimental studies have demonstrated benzodiazepines (a class of drug that includes diazepam) impair psychomotor skills performance. There is an epidemiological association between benzodiazepine use, increased motor traffic-accident risk and responsibility of the drivers for the crash (Longo et al., 2001; Bramness et al., 2003; Smink et al., 2008).

The pharmacologist also noted that there was no cocaine or benzoylecgonine (a major metabolite) reported to be present in the pilot’s blood but the cocaine metabolite methylecgonine was detected. They further stated that, while this confirmed the pilot had used cocaine within the previous few days, methylecgonine does not produce impairment although the possibility of impairment due to the ‘crash phase’ or withdrawal phase could not be excluded as being a possible factor in the accident. Cocaine effects on skills performance include risk-taking, inattentiveness and poor impulse control. In the withdrawal phase, the user can experience fatigue, sleepiness and inattention (Couper & Logan, 2014 Revision).

Alprazolam can also impair psychomotor skills (Baselt, 2001) and even at therapeutic blood concentrations, it can cause profound impairment of psychomotor skills required for complex tasks such as driving (Verster et al., 2002; Bramness et al., 2003; Leufkens et al., 2007). However, the pharmacologist indicated that, at the level detected, it was unlikely there would have been impairment of the pilot’s psychomotor functions and it unlikely contributed to the accident.

The ATSB’s aviation medical specialist indicated that the presence and levels of these psychoactive drugs and prescription medications would not have increased the risk of heart attack.

Medical-related accident research

ATSB research report B2006/0170

The ATSB’s research report (B2006/0170) on Pilot Incapacitation: Analysis of Medical Conditions Affecting Pilots Involved in Accidents and Incidents 1 January 1975 to 31 March 2006 (Newman, 2007) found pilot incapacitation due to the effects of a medical condition or a physiological impairment represents a serious potential threat to flight safety. A search of the ATSB’s accident and incident database was conducted for medical conditions and incapacitation events between 1 January 1975 and 31 March 2006. Heart attack was the fourth highest form of pilot incapacitation behind gastrointestinal illness, smoke and fumes, and loss of consciousness.

There were 98 occurrences in which the pilot of the aircraft was incapacitated for medical or physiological reasons and in 10 occurrences (10.2%), the outcome of the event was a fatal accident. All the fatal accidents involved single-pilot operations, and in the majority of cases, heart attack was the cause. The second highest cause was loss of consciousness.

The results of this study demonstrated that the risk of a pilot experiencing an in-flight medical condition or incapacitation event was low. However, if the pilot experienced a heart attack the risk of a fatal accident occurring increased. The report also suggested that the aeromedical certification process must keep pace with the evolving nature of modern medical science to ensure that the risk of in-flight incapacitation remained low.

United States Federal Aviation Administration Office of Aerospace Medicine (DOT/FAA/AM‑18/8)

This study, DOT/FAA/AM-18/8 of Incidental Medical Findings in Autopsied U.S. Civil Aviation Pilots Involved in Fatal Accidents (Ricaurte, 2018) examined incidental medical findings (IMFs) reported in the autopsies of pilots who died in United States aircraft accidents from April 2013 through March 2016. Incidental medical findings are previously undiagnosed medical conditions that were incidentally discovered during the autopsy, which may or may not have been related to the cause of death or of the accident.

Out of the selected pilots, 42% were found with IMFs reported in the autopsy. Cardiovascular abnormalities were the most common IMF (85%). The National Transportation Safety Board determined a medical issue was either the probable cause or a contributory factor in 12.2% of accidents with IMFs. The report noted that, while in commercial operations with 2 pilots, the other pilot carries out the flying duties, in single pilot operations, the outcome of the event is usually catastrophic. Epidemiological studies showed that in 15% of patients with coronary heart disease, sudden cardiac death is the initial coronary event.

Similar occurrences

ATSB investigation AO-2008-021

On 18 March 2008, a Pitts S-2A aircraft impacted the ground 7 km north-east of Camden, New South Wales, fatally injuring the occupant of the rear cockpit. The occupant of the rear cockpit, an experienced aerobatic pilot, was undergoing a routine flight review with an instructor. During a practice forced landing, the pilot stopped responding to instructions and commands, so the instructor took control of the aircraft. A powerful nose-up force began acting on the control column and the aircraft entered an incipient aerodynamic stall.[27] The instructor recovered the aircraft from the stall but, this came too late to prevent a collision with trees. Post-mortem examination of the pilot found they had severe heart disease. Expert medical opinion considered it likely that the pilot experienced an incapacitating event as a result of their heart disease.

ATSB investigation AO-2010-004

On 22 January 2010, a Victa Airtourer 115/A1 was landed safely on Miles Beach, Bruny Island, Tasmania. The pilot, being the sole occupant, shut down, exited and secured the aircraft before leaving it on the beach and walking away. The pilot was found deceased about 300 m from the aircraft. A post-mortem revealed the pilot had died as the result of a heart attack.

ATSB investigation AO-2018-057

On the afternoon of 17 August 2018, the pilot of a Kawasaki Heavy Industries BK117 helicopter was conducting fire-bombing operations approximately 9 km west of Ulladulla, New South Wales. On the fifth fire-bombing circuit, at this location, the pilot filled the slung Bambi Bucket (bucket) without incident from a nearby dam and departed towards the fire area. Shortly after, the helicopter diverted off course, the bucket and longline became caught in trees and the helicopter collided with terrain. The pilot was fatally injured, and the helicopter was destroyed. The pilot’s post-mortem identified 2 heart conditions, one of which was coronary heart disease that was capable of causing sudden impairment and incapacitation.

ATSB investigation AO-2022-009

On 28 February 2022, the crews of 3 Robinson R44 helicopters were preparing to conduct crocodile egg collection in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory. The crews of 2 of the R44 helicopters collecting crocodile eggs nearby became concerned that they had not heard any communications from the crew of the third helicopter, which they reported was unusual. One of those helicopters returned to the area where they were last seen and found the fatally injured egg collector on the ground and the pilot, having sustained serious injuries, laying beside the helicopter that had collided with terrain.

The pilot’s subsequent toxicology results detected 2 metabolites of cocaine. On the basis that the metabolites indicate exposure to cocaine, the detected levels indicated the pilot had not been exposed to cocaine within the previous 24 hours and may not have been affected by cocaine on the accident day. There was insufficient evidence to enable an assessment of whether the drug contributed to the development of the accident. However, the indication of exposure to cocaine is highlighted, as the effects of cocaine and post-cocaine exposure clearly increase risk to aviation activities. The post-cocaine exposure effects can include fatigue, depression and inattention.

ATSB investigation AO-2023-001

On 2 January 2023, the operator was conducting a series of scenic flights in 2 Eurocopter EC130B4 helicopters. The flights were performed under the visual flight rules from its base with the helicopters operating from separate helipads about 220 m apart. As one helicopter was preparing to land, the other helicopter took off. Shortly after, both helicopters collided. The landing helicopter was able to make a safe landing but the helicopter taking off crashed with the occupants being seriously or fatally injured.

The toxicology report for the fatally injured pilot showed a positive result for cocaine metabolites and the cutting agent levamisole. The ATSB’s interim investigation report found that, although it was unlikely the pilot would have had any psychomotor skill impairment on the day of the accident, it was not known whether post-cocaine exposure effects of the drug, which can include fatigue, depression and inattention, had any effect on the performance of the pilot.

Safety analysis

Introduction

On the afternoon of 6 October 2022, while flying at low level over Maitland Vale, New South Wales, a Bell 206B helicopter, registered VH-PHP, rolled markedly and descended rapidly, colliding with a riverbank. The helicopter was destroyed, and the pilot was fatally injured.

This analysis will consider the possible explanations for why the helicopter deviated from the pilot’s intended track and the final moments of the flight. It will also discuss the importance of disclosing medical information to CASA and the use of psychoactive drugs.

Pilot incapacitation and collision with terrain

The pilot deviated from the defined VFR lane and flew for periods at low level before the helicopter departed controlled flight. The ATSB considered a number of possible reasons to explain these events.

Pilot manoeuvring

The manoeuvring performed when approaching Tocal and the subsequent deviation outside the VFR lane and flight at low level was unexpected given the pilot’s intention to track to Warnervale. At one point during the deviation, the helicopter slowed to 22 kt and descended to 120 ft above ground level, which could be interpreted as an approach to land, but the pilot then climbed away. It was also noted that the pilot did not respond to calls made by air traffic control.

The pilot did not indicate to anyone their intention to deviate from the VFR lane and there was no known reason for the pilot to diverge from the track. To the contrary, the pilot stated to family by phone call just prior that the helicopter was flying well, and they would arrive at their destination in a short amount of time and that time would not have accommodated the deviation. The continued broadcasting by the pilot’s navigation software on their phone throughout the entire flight was evidence the pilot had a functional navigational aid.

Helicopter serviceability

While there were varying accounts by witnesses regarding the engine sound that could not be resolved and the helicopter had been in maintenance, the wreckage examination found no pre‑existing issues (mechanical or structural) that would have prevented normal operation. Numerous signatures of engine and driveshaft rotation were found indicating the powerplant and rotor system were functional. There were minimal signs of mast bumping, and the mast fractured in torsional overload indicating it failed on main rotor blade contact with the ground and the pilot did not excessively manoeuvre the helicopter.

Meteorological conditions

The weather forecast for the flight indicated some areas of low cloud and reduced visibility enroute, which could potentially explain the unexpected manoeuvring when near Tocal. However, an experienced pilot who was in the vicinity of the accident site reported the conditions as suitable for VFR operations. This was consistent with the meteorological equipment observations recorded at nearby Maitland Airport. Other witnesses near the VFR lane also reported weather consistent with these observations. Therefore, there was no evidence to indicate that the weather conditions directly contributed to the flight track deviation or the accident.

Pilot distraction

Distractions can occur unexpectedly, during any phase of flight, but when they have contributed to a safety occurrence, they have most often resulted in an incident rather than an accident (ATSB, 2006). There were no passengers on board, no other aircraft traffic was reported in the area at their altitude, and there was no evidence of any technical issues with the helicopter. While the pilot had been making phone calls, this was through the Bluetooth headset, which has simple handling. In addition, the flight time from Tocal and Vacy to the accident was 15 minutes and 5 minutes respectively, which should have been sufficient time to respond to the distraction and react appropriately. This included conducting a precautionary landing if the pilot had experienced a minor medical event. Therefore, a distraction event that was of sufficient magnitude and duration to result in the pilot losing awareness of their location and flightpath for this amount of time was considered to be unlikely. Further, distraction at the end of the flight was possible but considered unlikely due to the steep angle of pitch and bank prior to impact, which would not go unnoticed by an experienced pilot.

Pilot incapacitation

Pilot incapacitation is operationally defined as (International Civil Aviation Organization, 2012):

…any physiological or psychological state or situation that adversely affects performance.

Incapacitations can be divided into two operational classifications: “obvious” and “subtle”. Obvious incapacitations are those immediately apparent...onset can be “sudden” or “insidious” and complete loss of function can occur. Subtle incapacitations are frequently partial in nature and can be insidious because the affected pilot may look well and continue to operate but at a less than optimum level of performance. The pilot may not be aware of the problem or capable of rationally evaluating it.

ATSB research (ATSB, 2016) has shown that in-flight incapacitation can result from a variety of reasons, including changes in environmental conditions during the flight, the development of an acute medical condition, or the effects of a pre-existing medical condition.

The air temperature at nearby Maitland Airport was not excessive. The pilot had finished a short phone call about 60 seconds before the accident. As such, it was unlikely the pilot had fallen asleep leading up to the accident, although it could not be discounted that this occurred immediately prior to the impact. Also, the pilot was reported to be experiencing a head cold from which they were recovering. However, this was unlikely to be a source of distress enough to not permit continued control of the helicopter.

The pilot had notable changes in health during previous years including weight fluctuations, periods of high blood pressure and high cholesterol, insomnia, and lower back pain, for which the pilot had been prescribed various medications.

In the 12 months prior to the accident, the pilot completed their aviation medical and was found to be below the baseline required for further cardiac assessment. Although, given the pilot’s medical history and job stressors, the designated aviation medical examiner (DAME) and pilot elected to conduct further cardiac testing. The assessment found only minor to moderate cardiac disease and that the pilot was at low risk of a significant cardiac event.

However, the pilot’s post‑mortem examination found severe coronary atherosclerosis within all 3 major coronary arteries with at least 80% lumen stenosis observed. The ATSB’s aviation medical specialist noted that this could result in incapacitating chest pain leading to distraction and declining consciousness. This may possibly explain the unexpected deviation from the pilot’s intended track and the witness observations of the helicopter rolling markedly and descending rapidly before colliding with the riverbank. Nevertheless, it was not possible to forensically determine if the pilot experienced a heart attack prior to the accident. This is consistent with the ATSB research, which indicated it was likely that cardiovascular problems featured more prominently in general aviation accidents, but evidence of this was often difficult to establish with certainty, particularly in fatal accidents (ATSB, 2016).

The pharmacological influence of the medication and controlled substances detected was assessed by a forensic pharmacologist and an aviation medical specialist. While the levels of diazepam and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in the pilot’s blood sample were considered to result in some impairment of cognitive and psychomotor function, they were not at levels likely to exacerbate the pilot’s cardiac condition.

Despite this, in the absence of other reasonable scenarios to explain the unexpected events leading to the collision with terrain, the most plausible explanation was that the pilot likely experienced some level of incapacitation. However, the ATSB could not conclusively determine if this was due to a cardiac event, related to the medication and controlled substances, a combination of both, or for other unknown reasons.

Coronary artery disease

While a previous cardiac assessment identified the pilot had minor to moderate cardiac disease, the post-mortem found severe coronary atherosclerosis within all 3 major coronary arteries. With this level of disease, the ATSB’s aviation medical specialist advised that the pilot was at risk of a sudden incapacitating cardiac event. Similarly, the forensic pathologist also noted that the extent of the disease was a risk factor for sudden death. The post-mortem observations would suggest that the pilot’s cardiac disease had significantly increased in the period leading up to the accident.

Prior accidents and ATSB research have shown that, for fatal accidents with medical-related causes, coronary artery disease is one of the leading reasons for incapacitation, and for single‑pilot operations the majority leads to a fatal accident. Likewise, cardiovascular abnormalities were the most common incidental medical findings identified in pilot autopsies in the United States.

In this case, although it could not be determined if the pilot had experienced a heart attack, it remained a significant risk factor for the pilot. The initiation of a cardiac event can become so debilitating that the pilot becomes physically unable to control their own movements and thus the flightpath of the aircraft, which is particularly crucial in single-pilot operations.

Disclosure of medical information

As the holder of a pilot’s licence, the person is required to apply and obtain a medical certificate of an appropriate class if the person wishes to exercise the privileges of that licence. Aviation medical certificates have a period of validity, depending on their class, and need to be reapplied for at their expiry. As part of the medical process, the pilot is required to answer the DAME’s questions regarding their health and provide historical information so CASA can determine if the pilot meets the relevant medical standard. This includes the pilot completing a pre-medical questionnaire, which is reviewed by the DAME at the medical examination.

The DAME was not aware of the medications the pilot had been prescribed as ongoing treatment for insomnia (Alprazolam and Amitriptyline hydrochloride), as they had not been declared by the pilot during their medical examinations. These 2 medications were classified by CASA as category D drugs, which would have made the pilot ineligible to receive an aviation medical certificate. The Alprazolam, which was found in the pilot’s blood sample, was a Therapeutic Goods Administration Schedule 8 controlled drug.

The pilot also did not declare a spinal operation conducted 12 months before their last aviation medical examination, though the outcome of this was covered by a range of motion tests conducted by the DAME, which the pilot passed.

Medications and chronic conditions declared to a DAME permit medical conditions to be managed appropriately. Where an issue exists, alternative treatments and medications more compatible with aviation can be trialled, thereby permitting the pilot to manage both their own personal risks as well as those to aviation safety. A pilot should not exercise the privileges of their licence while taking a prohibited medication and should consult CASA or their DAME if they are unsure of a medication’s categorisation.

Psychoactive drugs and medications incompatible with aviation

The pilot’s blood sample contained psychoactive drugs, their metabolites and a cutting agent. In addition, the pilot had 2 medications determined by CASA to be incompatible with aviation safety. None of these drugs were permitted to be used in conjunction with flying.

The levels of diazepam detected were considered to be in the therapeutic range.

The family reported that the pilot reported operations were normal during a phone call during the flight. Also, the pilot had been flying for about 2 hours without any apparent issues. Therefore, there was insufficient evidence to enable an assessment of whether the drugs and medications alone contributed to the accident. However, the forensic pharmacologist advised that some of these drugs were at levels where some impairment of the high-level psychomotor skills required for flying would be expected. In addition, at the levels detected for some of these drugs, there is a notable increase in risk-taking.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the collision with terrain involving Bell Helicopter 206B, VH-PHP, 6.5 km east north-east of Maitland Airport, New South Wales on 6 October 2022.

Contributing factors

- While at low level, the pilot likely experienced an incapacitating event, leading to a collision with terrain.

Other factors that increased risk

- The pilot had severe coronary artery disease, which is known to reduce the supply of blood to the heart muscle. This can cause chest pain, dizziness, shortness of breath and possible incapacitation.

- The pilot did not disclose their use of prescription medicines to the Civil Aviation Safety Authority. This precluded specialist consideration and management of the ongoing flight safety risk the prescribed medications posed.

- The presence of metabolites of controlled substances and prescription medications in the pilot's blood stream had the potential to affect their performance and ability to safely operate the helicopter.

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- Coroner’s Court of NSW

- NSW Police Service

- NSW Forensic Medicine Service

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- the helicopter owner

- the maintenance organisation for VH-PHP

- Airservices Australia

- OzRunways

- Services Australia

- Bureau of Meteorology

- the pilot’s medical practitioners

- the witnesses.

References

Australian Transport Safety Bureau. (2016). Pilot incapacitation occurrences 2010-2014 (AR‑2015-096). Retrieved from https://www.atsb.gov.au/publications/2015/ar-2015-096/

Australian Transport Safety Bureau. (2007). Analysis of Medical Conditions Affecting Pilots Involved in Accidents and Incidents: 1 January 1975 to 31 March 2006. Retrieved from https://www.atsb.gov.au/sites/default/files/media/32864/b20060170.pdf

Baselt, R (2001). Drug effects on Psychomotor Performance. Biomedical Publications, California.

Baselt RC (2017). Disposition of toxic drugs and chemicals in man. 11th Edn. Biomedical Publications,California.

Bramness, J.G., Skurtveit, S. & Morland, J (2003). Testing the benzodiazepine inebriation-relationship between benzodiazepine concentration and simple clinical tests for impairment in a sample of drugged drivers. Eur. J. Pharmacol., 59:593-601.

Couper, F.J. & Logan, B.K. (2014 revision). Drugs and Human Performance Facts Sheets. Technical Report DOT HS 809 725, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Washington DC.

International Civil Aviation Organization. (2012). Doc 8984 Manual of Civil Aviation Medicine (3rd ed.). Retrieved from https://www.skybrary.aero/bookshelf/books/2242.pdf

Longo, M.C., Lokan, R.J. & White, J.M. (2001). The relationship between blood benzodiazepine concentration and vehicle crash culpability. J. Traffic Med., 29:36-43

Leufkens, T.R., Verneeren, A., Smink, B.E., van Ruitenbeek, P. & Ramaekers, J. G. (2007). Cognitive, psychomotor and actual driving performance in healthy volunteers after immediate and extended release formulations of alprazolam 1 mg. Psychopharmacology (Berl.), 191(4):951-959.

National Safety Council Committee on Alcohol and Other Drugs. (2012). Position on the Use of Cannabis (Marijuana) and driving. J. Anal. Toxicol., 37:47-49

Ricaurte E (2018) DOT/FAA/AM-18/8 Incidental Medical Findings in Autopsied U.S. Civil Aviation Pilots Involved in Fatal Accidents

Smink, B.E., Lusthof, K.J., de Gier, J.J., Uges, D.R.A. & Egberts, A.C.G. (2008). The relation between the blood benzodiazepine concentration and performance in suspected impaired drivers. J. Forensic & Legal Medicine, 15:483-488.

Verster, J.C., Volkerts, E.R. & Verbaten, M.N. (2002). Effects of alprazolam on driving ability, memory functioning and psychomotor performance: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Neuropsychopharmacology 27(2): 260-269.

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- pilot’s medical practitioners

- consultant pharmacologist

- consultant aviation medical specialist.

Submissions were received from the Civil Aviation Safety Authority and a medical practitioner. The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2024

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] Visual flight rules (VFR): a set of regulations that permit a pilot to operate an aircraft only in weather conditions generally clear enough to allow the pilot to see where the aircraft is going.

[2] A VFR route is a designated track usually in an area of high-density traffic or restricted airspace to enable safe separation of VFR traffic. It is also referred to as a VFR lane.

[3] These restricted zones cover from ground level to an altitude of 10,000 ft radially around Williamtown Airport and are used by military aircraft.

[4] The pilot reportedly flew with a Bluetooth enabled aviation headset.

[5] The last position indicated on the track was the last reliable GPS fix. The OzRunways system reported 8 additional points, but these were discarded as being unreliable due to reflected signals.

[6] OzRunways is an electronic mobile application, utilising approved data for electronic maps, and used for navigation.

[7] Cloud cover: in aviation, cloud cover is reported using words that denote the extent of the cover – ‘scattered’ indicates that cloud is covering between a quarter and a half of the sky, ‘broken’ indicates that more than half to almost all the sky is covered, and ‘overcast’ indicates that all the sky is covered.

[8] METAR: a routine report of meteorological conditions at an aerodrome. METAR are normally issued on the hour and half hour.

[9] For VFR operations, when flying below the height of 3,000 ft above mean sea level or 1,000 ft above ground level (whichever is the higher) in Class G non-controlled airspace, a pilot is required to have 5,000 m flight visibility and to be clear of cloud.

[10] Mast bumping: abnormal contact between the main rotor hub and the rotor mast which, if excessive, could severely damage the mast, or result in the separation of the main rotor system from the helicopter.

[11] A lumen is the inside space of a tubular structure, such as an artery or intestine.

[12] Stenosis is the abnormal narrowing of a blood vessel or other tubular organ or structure.

[13] Myocardial ischemia occurs when blood flow to the myocardium (the muscular tissue of the heart) is obstructed by a partial or complete blockage of a coronary artery by atherosclerosis.

[14] Arrhythmia, or irregular heartbeat, is an abnormal rate or rhythm of the heartbeat. The heart may beat too quickly, too slowly, or with an irregular rhythm.

[15] Myocardial infarction, colloquially known as ‘heart attack’, is caused by decreased or complete cessation of blood flow to a portion of the myocardium.

[16] Atherosclerosis is the buildup of fats, cholesterol, and other substances in and on artery walls. This buildup is known as plaque. The plaque can cause arteries to effectively narrow, blocking blood flow.

[17] Perivascular fibrosis is the increased amount of connective tissue in the heart vessels, which increases tissue stiffness.

[18] A myocyte is a contractile cell (muscle cell).

[19] Ventricular tachycardia is a type of irregular heart rhythm (arrhythmia) characterised by the lower heart chamber contracting poorly (quivering) but in a coordinated manner resulting in poor pumping function.

[20] Ventricular fibrillation is a type of irregular heart rhythm (arrhythmia) characterised by the lower heart chamber contracting very rapidly but in an uncoordinated manner resulting in poor pumping function.

[21] Diastolic blood pressure is how much pressure the blood is exerting against the artery walls while the heart muscle is resting between contractions.

[22] Left ventricular hypertrophy is thickening of the walls of the lower left heart chamber.

[23] Schedule 8 controlled drugs are substances that should be available for use but require restriction of manufacture, supply, distribution, possession and use to reduce abuse, misuse and physical or psychological dependence (Therapeutic Goods (Poisons Standard - October 2022) Instrument 2022).

[24] Schedule 4 is for prescription only medicine. These are substances, the use or supply of which should be by or on the order of persons permitted by State or Territory legislation to prescribe and should be available from a pharmacist on prescription. However, some prescription medications have further specified controls applying to possession or supply. These are often referred to as restricted drugs or Schedule 4D medications (Therapeutic Goods (Poisons Standard - October 2022) Instrument 2022).

[26] It should be noted that post-mortem blood samples are whole blood samples, but the reported therapeutic ‘blood’ concentrations from clinical studies are generally plasma concentrations. The blood/plasma ratio for diazepam is reported as being about 0.6 (Baselt 2017). Therefore, the reported blood concentration would be very conservative, and a plasma concentration would have been around 40% higher.

[27] Aerodynamic stall: occurs when airflow separates from the wing’s upper surface and becomes turbulent. A stall occurs at high angles of attack, typically 16˚ to 18˚, and results in reduced lift and increased drag.