Executive summary

What happened

On 12 August 2022, a Beech Aircraft Corp 95-B55, registered VH‑ALR and operated by Hartwig Air, was being repositioned to Parafield Airport, South Australia after completing a series of non‑scheduled air transport passenger flights in the north of the state.

Weather conditions at Parafield when the aircraft arrived required the pilot to conduct an instrument approach procedure. During that approach, about 20 km north-north-east of Parafield and while flying in cloud, the pilot descended the aircraft below a segment minimum safe altitude, activating an automated minimum safe altitude warning to air traffic control.

An air traffic controller established communication with the pilot and advised them of their descent below the segment minimum safe altitude and issued a safety alert. The pilot immediately climbed the aircraft above the segment minimum safe altitude, then continued the approach and landed without further incident.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that the pilot was experiencing increased workload during the approach in cloud and turbulent conditions and did not detect their inadvertent descent below the segment minimum safe altitude, until they received the warning from the air traffic controller.

The activation of the air traffic control minimum safe altitude warning instigated communication checks with the pilot, which resulted in them being alerted to the aircraft’s descent below the segment minimum safe altitude and an immediate climb was commenced.

While conducting the approach, the pilot reported that they had been referring to a hand-held paper copy of the instrument approach procedure chart, as the aircraft’s control yoke did not have a chart holder, nor did the pilot have a document holder or kneeboard available, which increased the difficulty monitoring the check altitudes and segment minimum safe altitudes.

The aircraft was about 850 ft above the recommended profile with 7 NM to run when the pilot decided to continue the approach. Continuing the approach from that position required a higher‑than-normal descent rate and had potential to increase the pilot’s workload.

What has been done as a result

Following this incident, the operator arranged for an experienced instrument flight examiner to conduct additional training with the pilot in a synthetic training device.

Safety message

Conducting an instrument approach in instrument meteorological conditions is a high workload procedure, requiring close monitoring by the flight crew of the aircraft’s vertical and lateral navigation to assure it remains clear of terrain.

An important part of conducting the instrument approach required the continuous monitoring of the aircraft’s altitude relevant to the various segment minimum safe altitudes and having the instrument approach procedure chart available in a suitable location that minimises additional workload.

Pilots also need to remain vigilant about the relationship between the procedure commencement altitude and the constant descent final approach path, including that the correct waypoint has been identified for managing the descent profile and ensuring the distance-based check altitudes are correctly interpreted.

The investigation

| Decisions regarding the scope of an investigation are based on many factors, including the level of safety benefit likely to be obtained from an investigation and the associated resources required. For this occurrence, a limited-scope investigation was conducted in order to produce a short investigation report, and allow for greater industry awareness of findings that affect safety and potential learning opportunities. |

The occurrence

On 12 August 2022, a Beech Aircraft Corp 95-B55, registered VH-ALR and operated by Hartwig Air, was being repositioned to Parafield Airport, South Australia after completing a series of non‑scheduled air transport passenger flights in the north of the state. Those flights had been conducted over two days and were operated under the instrument flight rules (IFR).[1]

The flights conducted on the day of the incident commenced in Innamincka and after refuelling the aircraft at Leigh Creek, the pilot had disembarked their passengers at Port Augusta. Weather conditions for those flights were influenced by a slow-moving low-pressure system to the south of Adelaide, resulting in a south-westerly onshore flow with low cloud, showers, reduced visibility and areas of moderate and severe turbulence. The pilot conducted area navigation (RNAV) global satellite system (GNSS) instrument approaches at Leigh Creek and Port Augusta.

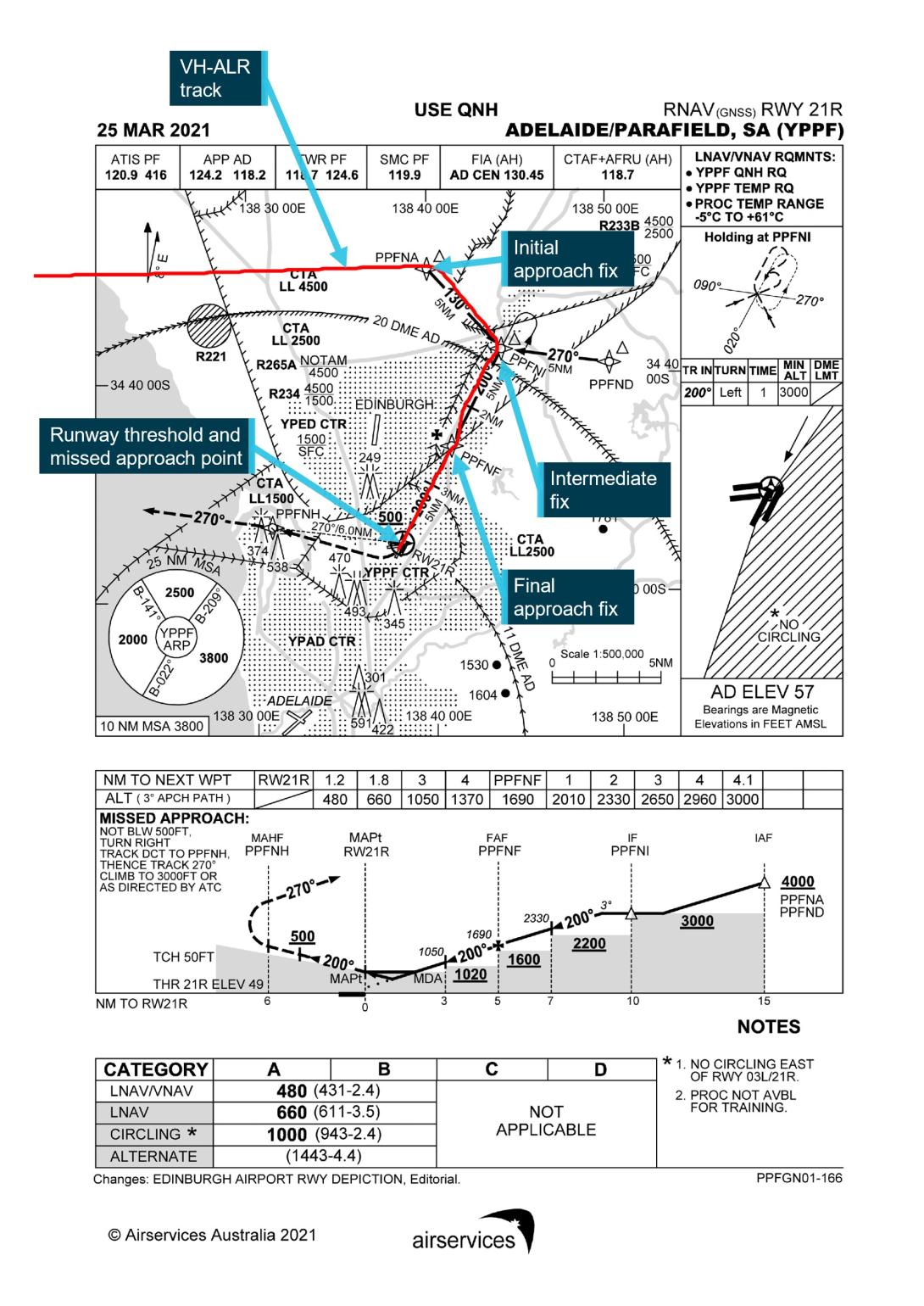

The aircraft departed Port Augusta just after midday (local time) and was climbed to 5,000 ft above mean sea level for the flight to Parafield. As the aircraft approached Adelaide, the weather conditions in the Parafield control zone were unsuitable for a visual arrival and the approach controller instructed the pilot to track the aircraft to waypoint PPFNA,[2] one of the initial approach fixes (IAF) for the Parafield RNAV GNSS RWY 21R[3] instrument approach procedure.[4] The instrument approach procedure chart overlaid with the aircraft’s ground track is depicted at Figure 1.

Figure 1: Parafield RNAV GNSS RWY 21R instrument approach procedure chart with VH‑ALR track overlaid

This image depicts the Parafield RNAV GNSS RWY 21R instrument approach procedure chart, overlaid with the aircraft’s ground track.

Source: Airservices Australia (ASA), modified by ATSB

The aircraft was 7 NM west of the IAF, when the approach controller cleared the pilot to descend from 5,000 ft to 4,000 ft, which was the instrument approach procedure’s minimum commencement altitude. The aircraft was approaching the IAF at an altitude of 4,000 ft when the controller issued the pilot clearance to commence the approach and to contact Parafield tower at the intermediate fix (IF), PPFNI.[5], [6]

Weather conditions for the approach were reported as turbulent, affecting the aircraft’s speed and attitude control, with the aircraft passing in and out of cloud. The pilot recalled that due to the conditions and to assist with speed control during the initial stages of the descent and approach, they had extended the landing gear and selected approach flap prior to the IAF.

After passing the IAF, the pilot turned the aircraft to track to the IF and commenced descent from 4,000 ft. The segment minimum safe altitude between the IAF and IF was 3,000 ft. During the first part of that segment, the pilot descended the aircraft at an appropriate rate. The aircraft was about 2 NM from the IF when it reached and then descended below the segment minimum safe altitude.

As the aircraft approached and then passed the IF, the descent rate increased slightly, with the pilot turning the aircraft to intercept the final approach track (Figure 1) at an altitude of about 2,000 ft. After the IF, the segment minimum safe altitude reduced to 2,200 ft.

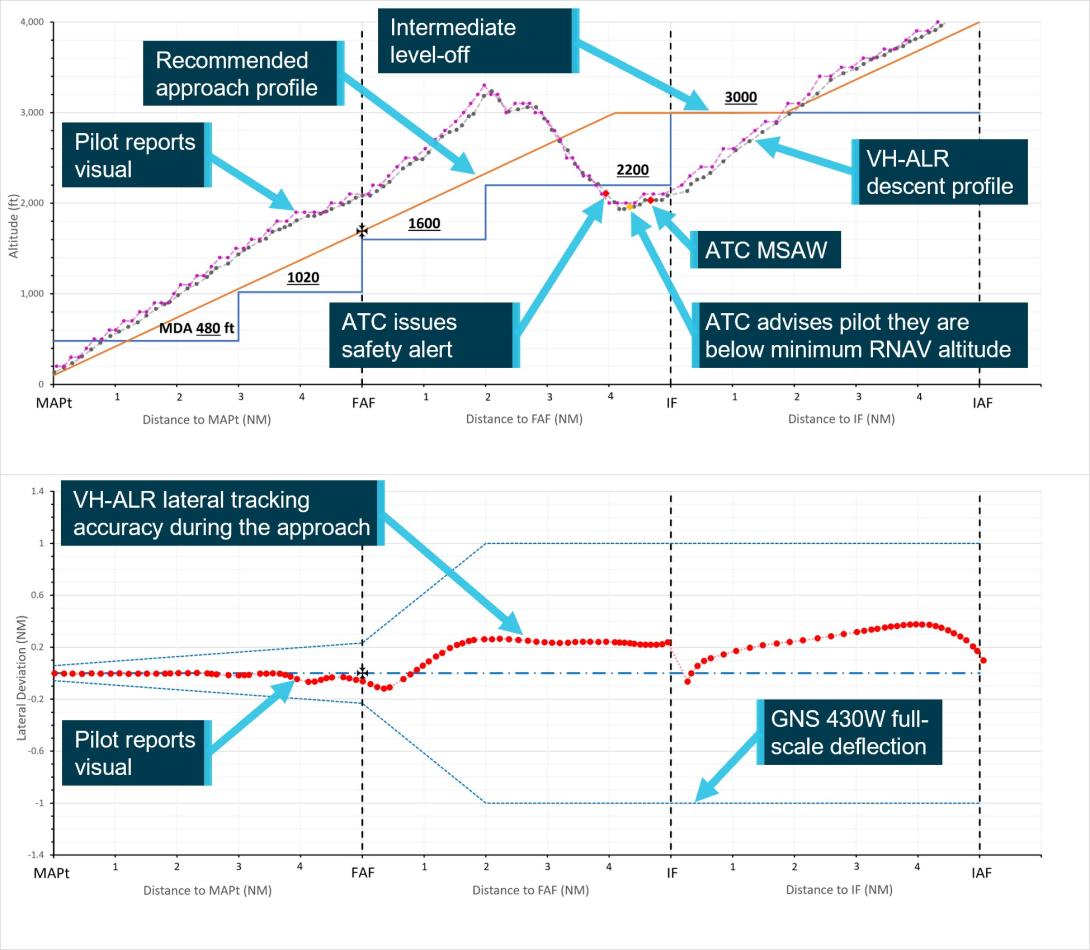

Soon after the aircraft had passed the IF, the approach controller received an automated minimum safe altitude warning (MSAW) from the air traffic control (ATC) software-based monitoring system and attempted to establish radio contact with the pilot. The approach controller then used their ‘hotline’ intercom to contact the Parafield tower controller to check if the pilot had transferred to their frequency. The tower controller established communication with the pilot, advised them that they had descended below the minimum RNAV GNSS segment altitude and requested they confirm their flight conditions. The pilot reported that they were still in cloud. The tower controller then issued a safety alert and suggested an immediate climb. The pilot was already responding to the controller’s previous transmission and had entered a climb to establish the aircraft above the segment minimum safe altitude (Figure 2). In subsequent communication with the tower controller, the pilot elected to continue the approach.

The aircraft’s lateral track was within the required lateral tracking tolerances passing the final approach fix (FAF) PPFNF and about 300 ft above the recommended approach profile. The aircraft was about 4 NM from the runway at an altitude of 1,900 ft when the pilot reported to the tower controller that they were ‘visual’ and the final part of the approach was flown at an airspeed of about 100–110 kt.

The aircraft descent profile during the approach and the lateral tracking accuracy with reference to the global positioning system (GPS) course deviation indicator’s full-scale deflection is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Descent profile and lateral tracking accuracy during instrument approach

The top graph depicts the descent profile of VH-ALR relative to the segment minimum safe altitudes during the instrument approach procedure. The grey dotted line is altitude derived from ADS-B data broadcast by the aircraft (25 ft increments), the purple line is the aircraft’s Mode C transponder altitude (100 ft increments). The lower image displays the lateral tracking accuracy of the aircraft during the instrument approach, together with the position of the full-scale deflection indicated on the course deviation indicator and the display of the GNS 430W.

Source: ATSB illustration of relevant data from the instrument approach procedure, Airservices Australia and FlightRadar24.

Context

Pilot information

The pilot held a Commercial Pilot Licence (Aeroplane) with an instrument rating and multi-engine endorsement.[7] The pilot was required to use vision correction when exercising their licence privileges. At the time of the incident, they had accrued a total aeronautical experience of approximately 1,200 hours, including 90 hours on multi-engine aircraft, 50 hours of which were on Baron series[8] aircraft. Most of the pilot’s Baron flying had been conducted under the instrument flight rules (IFR). Included in their aeronautical experience was about 60 hours of instrument flight time.

The pilot had completed an instrument proficiency check within the previous 12-month period and had recently completed a practice RNAV approach in VH-ALR at Ceduna. Prior to departing on the series of flights associated with the charter, the pilot had also conducted practice instrument landing system and RNAV approaches for Adelaide Airport, using a Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA)-approved synthetic training device.

The pilot recalled that they were well rested prior to commencing duty on the morning of the incident. Upon arriving at Parafield Airport, they had been on duty for more than 5 hours and had flown about 4 hours, including sectors in turbulent conditions and with relatively high workload. For the instrument approach into Parafield, the pilot reported feeling ‘moderately’ tired.[9]

Aircraft information

The aircraft was equipped with a conventional set of analogue flight instruments. It was also fitted with a 2-axis autopilot, capable of providing control guidance in the pitch and roll axes. During their post-incident interview, the pilot recalled the autopilot functionality was useful during cruise, but they wouldn’t normally use it when conducting instrument approaches.

VH-ALR was equipped with two, 3-pointer pressure-sensitive altimeters, including one directly in front of the pilot. The altimeters responded to pressure variations in the atmosphere and indicated the aircraft’s altitude above the selected pressure datum, by the pilot reading the relationship between the three indicating pointers.[10] These types of 3‑pointer altimeters are common in general aviation aircraft. Research has shown that such altimeters can be associated with misreading errors, including misreading the altitude by 1,000 ft.[11]

The aircraft was equipped with an assigned altitude indicator, which was designed to be used as a reminder of the altitude assigned by air traffic control (ATC). Altitudes could be manually set by means of individual thumb wheels, but no aural or visual alerts were provided when reaching or leaving the set altitude. The aircraft did not have an altitude alerting system, nor was it required for the type of aircraft and operation.[12]

For conducting RNAV (GNSS) instrument approaches, the aircraft had two global positioning system (GPS) receivers, a Garmin GNS 430W and a Garmin GTN 750. The display panels for the GPS receivers were located to the right of the engine control quadrant. The GTN 750 comprised a moving map display with touch screen functionality and the GNS 430W included the unit’s operating controls and a smaller display panel. The GNS 430W was installed directly below the GTN 750. The selected instrument approach procedure would crossfill between the two units. Neither the GNS 430W or the GTN 750 units could provide vertical profile guidance during the approach.

Meteorological information

The pilot obtained the relevant metrological forecasts prior to departing Innamincka on the morning of the incident. The weather conditions encountered during the flights were consistent with the forecast.

Affecting the aircraft between Port Augusta and Parafield at the selected cruise altitude was broken[13] cumulus and stratocumulus cloud and south westerly winds of about 25 kt. Scattered showers of rain with reduced surface visibility (4,000 m)[14] were forecast with towering cumulus cloud and isolated[15] light to moderate thunderstorms with rain and reduced surface visibility (2,000 m) with cumulonimbus cloud. Moderate turbulence[16] was forecast in cumulus/stratocumulus cloud and severe turbulence[17] and icing in towering cumulus/cumulonimbus cloud and thunderstorms. The freezing level was forecast to be 5,500 ft.

The Parafield Airport forecast (TAF) current at the time VH-ALR departed Port Augusta indicated that an instrument approach would likely be required arriving Parafield, with light showers of rain and broken cloud, 1,600 ft above the aerodrome elevation. The Parafield aerodrome weather reports (METARs) were automatically generated every 30 minutes for routine reports, or as special reports (SPECI) at other times when one or more meteorological elements either deteriorated or improved around specified criteria. A SPECI report was issued 1300 (closest to the time of the aircraft’s arrival), indicating broken cloud 1,700 ft above the aerodrome and overcast cloud at 2,300 ft, but with surface visibility greater than 10 km. Those conditions indicated that a pilot conducting the RNAV GNSS RWY 21R approach and flying the recommended 3‑degree approach profile, could expect to become visual with the runway at about the final approach fix (FAF).

Instrument approach

A RNAV GNSS was a two-dimensional (2D) instrument approach procedure flown using an onboard GPS receiver that complies with relevant airworthiness certification standards, to generate lateral/tracking guidance and the distance to run to next waypoint, allowing for safe navigation of an aircraft operating in instrument meteorological conditions to land at an aerodrome. If the pilot establishes the required visual reference with the runway during the approach, they continue the approach and land. If the required visual reference is not established, the pilot conducts the procedure for a missed approach.

The RNAV GNSS instrument approach procedure chart includes the approach course (comprising a series of waypoints) and information relevant to the vertical navigation of the aircraft. The descent profile was designed to provide a constant descent final approach (CDFA) path from the procedure altitude[18] to an altitude from which a straight-in landing or a circling procedure can be completed. Significantly, the position at which the CDFA intersected the procedure altitude varied between approaches, but occurred during the intermediate or final approach segments. The CDFA angle was shown on the chart’s profile diagram, together with a CDFA altitude/distance scale and advisory crossing altitudes. After commencement of the CDFA, the profile diagram and altitude/distance scale also included the crossing altitude for each of the waypoints.

Each segment of the RNAV GNSS instrument approach procedure specified one or more segment minimum safe altitudes, which were identified by shading on the chart’s profile diagram. When conducting a CDFA, pilots were expected to follow the descent profile, but monitor the descent to ensure the aircraft remains at or above the applicable segment minimum safe altitude.[19]

The instrument approach procedures were pre-programmed in the GPS database from which the pilot selected and activated the required approach. The aircraft’s position relative to the approach course was indicated on the display panels of the GPS receivers and also on the instrument panel’s course deviation indicator displays. The display panel of the GNS 430W receiver provided various operational information for the pilot’s management of the approach, including the current approach segment, the distance to run to the next waypoint and the aircraft’s groundspeed.

The GPS receivers were equipped with receiver autonomous integrity monitoring (RAIM).[20] The pilot recalled they had checked for predicted RAIM outages before arming the approach and there were none indicated. There were no RAIM messages displayed during the conduct of the instrument approach, indicating that the GPS calculated positions were within the required tolerance to conduct the approach.

Operational information

The ATC recordings indicated the pilot had correctly completed the read-back of the QNH[21] provided by the approach controller and the transponder indicated altitude from VH-ALR was consistent with the aircraft operating at the assigned altitude.

The pilot used the aircraft’s flight instruments and flight controls to steer the required approach course, make the required turns to intercept the next approach segment and manage the vertical profile of the descent.

The pilot indicated during interview that they had access to a portable electronic device with electronic flight bag (EFB) capability.[22] At the time of the incident, the operator did not hold a CASA approval to use EFBs, so the pilot also carried printed paper copies of the instrument approach procedure.[23] The aircraft’s control yoke did not have a chart holder, nor did the pilot have a document holder or kneeboard available. Consequently, the pilot reported that the paper chart was held in their hand when referring to it during the approach, including when checking altitudes, tracks and distances.

The pilot had anticipated that weather conditions at Parafield could necessitate an instrument approach and that they had reviewed the Parafield RNAV GNSS approach procedure at breakfast on the morning of the incident and again, prior to departing Port Augusta. The pilot recalled that they had identified the number of segment minimum safe altitude steps during their preflight reviews and briefing of the Parafield RNAV GNSS instrument approach procedure, particularly noting the close proximity of the final approach profile to several of those steps and planned to fly a constant profile descent during the approach. Prior to commencing the approach, they had identified that 3,000 ft was the segment minimum safe altitude prior to the intermediate fix (IF) and did not intend to descend the aircraft below that altitude. When conducting any descent, their normal procedure was to self-announce when there was 1,000 ft to run, but on this occasion the procedure was of limited use given that the descent commenced 1,000 ft above the intermediate level-out altitude.

Approaching the IF the pilot recalled concentrating on managing the aircraft’s speed in the turbulent conditions and monitoring the distance to commence the turn to intercept the final approach track.

The pilot recalled that they had not yet reached the FAF when the tower controller advised them that they had descended below the minimum altitude, and immediately commenced a climb to above the segment minimum safe altitude. In those weather conditions, the pilot wanted to complete the approach and land as soon as practicable and when the controller asked their intentions, the pilot had elected to continue the approach.

The ATSB used the available data to estimate the aircraft’s airspeed during the final approach, which was within the required handling speeds for that approach segment.[24]

When reviewing the circumstances of the occurrence, the pilot felt those tasks had been prioritised to the detriment of their monitoring the aircraft’s altitude. The pilot did not believe that the descent below the segment minimum safe altitude was because they had misread the three‑pointer altimeter.

Since the occurrence, the pilot had considered that conducting the missed approach procedure was also an option, that could have helped manage any increased workload associated with continuing the approach and they had sufficient fuel to cover that contingency.

The pilot reviewed the Parafield RNAV GNSS RWY 21R instrument approach procedure after the occurrence and had compared that approach with the other procedures flown that day, they noted the variation between how the altitude/distance scales were presented and the waypoints that the altitudes and distances referred to.

The ATSB reviewed the instrument approach procedures flown by the pilot on the day of the incident and noted:

- arriving at Leigh Creek, the procedure profile depicted a level segment from the IAF to the IF, and the CDFA path commenced about 4.5 NM prior to the FAF

- arriving at Port Augusta, the procedure profile depicted the aircraft crossing the IAF at a constant altitude, but the CDFA path commenced about 1.9 NM prior to the IF

- arriving at Parafield from the IAF waypoints PPFNA or PPFND, the procedure profile depicted an intermediate descent commencing at the IAF, but with a segment minimum safe altitude of 3,000 ft until after passing the IF (PPFNI) with the CDFA path commending 4.1 NM prior to the FAF.

For all approaches flown that day, the altitude/distance scale on the profile diagram provided information for the CDFA path, including the waypoint crossing altitudes. In the case of the Parafield approach, the waypoint PPFNI was also denoted as an IAF at an altitude of 3,000 ft.[25]

Safety analysis

On 12 August 2022, a Beech Aircraft Corp 95-B55, registered VH-ALR was being operated on an instrument approach procedure into Parafield Airport, South Australia. During that approach and while flying in cloud and turbulent conditions, the pilot descended the aircraft below a segment minimum safe altitude, activating an automated minimum safe altitude warning to air traffic control. Air traffic control contacted the pilot and advised the pilot of their descent below the segment minimum safe altitude and issued a safety alert. The pilot immediately climbed the aircraft above the segment minimum safe altitude, then continued the approach and landed without further incident.

The ATSB was satisfied that the pilot was adequately rested prior to commencing their duty period. Although the pilot reported that their fatigue levels had increased during the flight, that was to be expected given the weather conditions during the flights conducted that day.

The ATSB concluded there were no issues with the set up or functionality of the aircraft’s altimeters, meaning correct altitude information was available to the pilot. As such, the following analysis will consider factors associated with the descent below minimum safe altitude, use of a paper copy of the instrument approach procedure chart, the pilot’s response to the minimum safe altitude alert warning and the resulting steeper than normal approach to land.

The weather conditions in the vicinity of Parafield required the pilot to conduct an instrument approach. The aircraft was maintaining 4,000 ft above mean sea level as it approached the initial approach fix PPFNA and had been configured to commence the instrument approach procedure. The initial descent from 4,000 ft was conducted at a rate that achieved an approximate 3-degree descent profile.

The pilot had stated that they had left 4,000 ft at commencement of the approach with the intention of levelling out at 3,000 ft. The pilot’s recollection was that descent below the segment minimum safe altitude was not the result of misreading the altimeter or instrument approach procedure, but more due to being distracted by workload in the turbulent weather conditions. That included monitoring the distance to run to the intermediate fix, to initiate the turn to intercept the track for the final approach. Conducting an instrument approach in instrument meteorological conditions added to a high workload procedure, requiring close monitoring of the aircraft’s vertical and lateral navigation by the pilot.

The instrument approach procedure included five segment minimum safe altitudes and the constant descent final approach (CDFA) path that passed close to those limits, which necessitated close monitoring during the descent. During the instrument approach, the pilot would have used one hand on the control column to fly the aircraft, and the other hand to operate the engine and other ancillary controls. The pilot’s use of a paper copy of the instrument approach procedure chart without a chart holder or kneeboard available, made the task of referring to the chart information less convenient and potentially increased the likelihood of misinterpreting check altitudes for the descent or segment minimum safe altitudes that applied.

Following the incident, the pilot reviewed the Parafield instrument approach procedure, together with the other procedures they had flown that day and correctly identified that each procedure’s CDFA path commenced at different positions in relation the initial approach and intermediate fixes. However, they probably had not correlated the relationship between the procedure altitude for commencement of the CDFA path and the significance of that position with the commencement of altitude/distance scale on the instrument approach procedure’s profile diagram. This increased the potential for the pilot to misinterpret the altitude/distance scale and associate the published altitude with the distance to run to an incorrect or out of sequence waypoint.

Although the pilot was experiencing a high workload as the aircraft approached the intermediate fix, they had accurately intercepted the inbound track and had immediately initiated a climb of the aircraft when the tower controller advised their descent below the minimum procedure altitude. Although the aircraft had descended below the segment minimum safe altitude, the lateral tracking of the aircraft was accurate and remained within the lateral tracking requirements for the RNAV GNSS procedure.

The pilot climbed the aircraft above the 2,200 ft segment minimum safe altitude for that stage of the approach and continued the climb. That resulted in the aircraft being about 850 ft above the recommended profile with 7 NM to run to the missed approach point when the tower controller asked the pilot their intentions, and the pilot indicated they would continue the approach. Continuing the approach from that position did require a higher-than-normal descent rate and had potential to increase the pilot’s workload. However, the pilot managed the descent of the aircraft to progressively intercept the approach profile, the aircraft’s speed was maintained within the required parameters for the approach and the lateral tracking was within the required tolerances. The aircraft was about 400 ft above the recommended CDFA path at the final approach fix, with 5 NM to run to the missed approach point and soon after, the pilot reported to the tower controller that they were visual.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the flight below minimum altitude involving Beech Aircraft Corp 95-B55, registration VH-ALR near Parafield Airport, South Australia on 12 August 2022.

Contributing factors

- Approaching the intermediate fix while conducting a RNAV GNSS approach in instrument meteorological conditions and turbulence, the pilot’s workload increased and they did not identify the inadvertent descent below the segment minimum safe altitude.

Other factors that increased risk

- The pilot reported that they were using a hand-held paper copy of the instrument approach procedure chart, which increased the difficulty monitoring the check altitudes and segment minimum safe altitudes for the various stages of the approach.

- After climbing the aircraft above the segment minimum safe altitude, the pilot elected to continue the approach which necessitated a steeper than normal descent.

Other findings

- The activation of the minimum safe altitude warning on the approach controller's console instigated communication checks with the pilot, which resulted in them being alerted to the aircraft’s descent below the segment minimum safe altitude and an immediate climb was commenced.

Safety actions

| Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. All of the directly involved parties are invited to provide submissions to this draft report. As part of that process, each organisation is asked to communicate what safety actions, if any, they have carried out to reduce the risk associated with this type of occurrences in the future. The ATSB has so far been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence. |

Safety action by Hartwig Air

Following this incident, the operator arranged for an experienced instrument flight instructor/examiner to conduct additional training with the pilot in a synthetic training device.

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- the pilot of VH-ALR

- Airservices Australia

- Bureau of Meterology.

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- the pilot of VH-ALR

- Hartwig Air

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Airservices Australia

- Bureau of Meterology.

There were no submissions received.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2024

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] Instrument flight rules (IFR): a set of regulations that permit the pilot to operate an aircraft in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC), which have much lower weather minimums than visual flight rules (VFR). Procedures and training are significantly more complex as a pilot must demonstrate competency in IMC conditions while controlling the aircraft solely by reference to instruments, rather than by outside visual reference. Typically, this means flying in cloud or limited visibility. IFR-capable aircraft have greater equipment and maintenance requirements.

[2] Waypoint: A defined position of latitude and longitude coordinates, primarily used for navigation. These waypoints were incorporated to the GPS receiver’s navigation database and could not be edited by the user. Regular updates were made to the navigation database and ensured the current/correct approach procedure was available.

[3] Runway number: the number represents the magnetic direction of the runway centreline, and is expressed in 10 degree increments of azimuth. The runway identification may include L, R or C as required for left, right or centre.

[4] An RNAV GNSS approach is a type of instrument approach procedure that uses a GPS receiver that complies with the relevant airworthiness certification standards, to provide lateral tracking information for the pilot to conduct the approach.

[5] The relatively late approach clearance was due to visual flight rules (VFR) aircraft operating in the Parafield circuit area. An approach clearance could only be issued once all the VFR aircraft operating in the Parafield control zone were on the ground.

[6] Waypoint PPFNI was the intermediate fix for the procedure when being conducted from offset sectors (PPFNA and PPFND). For a straight-in approach, PPFNI was designated as the IAF at an altitude of not below 3,000 ft.

[7] This included 2D and 3D instrument approach operations in instrument meteorological conditions, which included RNAV GNSS procedures. The pilot’s instrument rating and multi-engine endorsement was issued in 2017. Since that time, they had completed 2 instrument proficiency checks.

[8] The Baron series of aircraft includes the Beech Aircraft Corp 95-B55.

[9] During interview, the pilot was asked to make a subjective assessment of their fatigue level at the time of the occurrence, using the Samn-Perelli seven-point fatigue scale. The pilot estimated that they had started their duty period fully alert, wide awake (scale point ‘1’), but at the time of the occurrence their fatigue levels had increased, and they were moderately tired (scale point ‘5’).

[10] Hundreds of feet were indicated by a long and narrow pointer needle, thousands of feet by a short and wide pointer needle and tens of thousands of feet by a long/thin needle with a triangle symbol at the pointer’s tip.

[11] A summary of research and guidance regarding the design of altimeters is included in Appendix A of the ATSB Aviation Occurrence Report AO-2020-017, Controlled flight into terrain involving Cessna 404, VH-OZO 6 km south-east of Lockhart River Airport, Queensland, on 11 March 2020. This report is available to download from the ATSB website (www.atsb.gov.au).

[12] An altitude alerting system provides an aural alert (tone) and/or a visual alert when an aircraft on climb/descent approaches the designated altitude and when deviating from that altitude during cruise. Aircraft conducting IFR operations in controlled airspace were required to have either an assigned altitude indicator or an altitude alerting system. For piston-engine aircraft, an altitude alerting system was only required for IFR operations at altitudes 15,000 ft above the standard atmospheric pressure datum 1013.25 hPa.

[13] Broken describes cloud coverage between 5 to 7 eighths (oktas) of the sky (except for cumulonimbus and towering cumulus cloud).

[14] Scattered describes well separated features that affect or are forecast to affect, an area with a maximum spatial coverage from 50% to 75%.

[15] Isolated describes individual features that affect or are forecast to affect, an area with a maximum spatial coverage of up to 50%.

[16] Moderate turbulence describes appreciable changes in attitude and/or altitude in rapid bumps or jolts, but with the pilot being able to control the aircraft.

[17] Severe turbulence describes large abrupt changes in attitude and/or altitude, resulting in momentary loss of control of the aircraft flightpath.

[18] The procedure altitude accommodates a stabilised descent at a prescribed descent gradient/angle in the intermediate/final approach segments.

[19] Descent below the recommended CDFA to the segment minimum safe altitude can be conducted at pilot discretion but was not a recommended technique.

[20] Availability of RAIM during the conduct of an RNAV GNSS approach provides an assurance of the integrity of the navigation system and that the calculated position is within the required tolerance for the procedure being flown.

[21] QNH: the altimeter barometric pressure subscale setting used to indicate the height above mean seal level.

[22] An EFB can replace traditional paper products in an aircraft, store and display aviation data and perform calculations. This typically also includes functionality such as a moving map display with relevant information overlaid.

[23] Holders of an air operator certificate required CASA approval before their crews could use an EFB. Operators were required to provide CASA with an exposition including information, procedures, and instructions for the use of EFBs.

[24] The handling speed stipulated for a category B aircraft during the final approach segment was 85 to 130 kt.

[25] This configuration for the approach allowed aircraft arriving from the north-east to commence the approach at waypoint PPFNI.