Executive summary

What happened

On the afternoon of 16 September 2021, a Virgin Australia Airlines Boeing 737-8FE (B737) aircraft, registered VH-YIO, was conducting a scheduled passenger service from Sydney Airport, New South Wales (NSW), to Ballina Byron Gateway Airport (Ballina Airport), NSW. At the same time, a Cessna Caravan 208 (Caravan) aircraft, registered VH-YMV, taxied for a private instrument flight rules flight from Ballina Airport to Sunshine Coast Airport, Queensland.

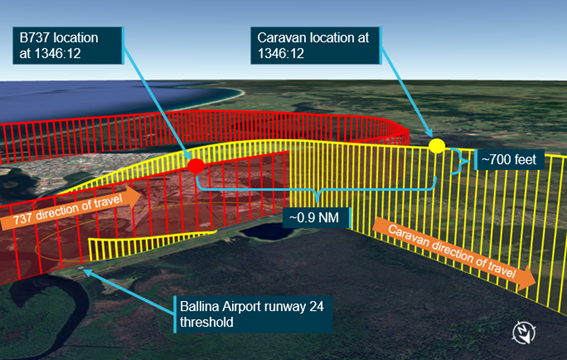

While the B737 was on final approach to land on runway 24, the Caravan was taxied onto the runway and a take-off was commenced towards the approaching B737. The flight crew of the B737 conducted a missed approach to avoid the Caravan, during which they received a traffic collision avoidance system traffic advisory. At the closest point of approach, the lateral separation between the 2 aircraft decreased to approximately 0.9 NM with vertical separation reducing to about

700 feet. At the time of the incident, the aircraft were operating within the airport’s broadcast area and were both receiving a surveillance flight information service (SFIS).

What the ATSB found

The ATSB’s investigation identified that the Caravan pilot had an incorrect mental model of the traffic scenario, believing the B737 would land behind them on runway 06, rather than runway 24. The Caravan pilot had been provided with traffic information by the Ballina Airport SFIS controller, but the controller had not specified the landing direction of the B737 and the pilot had not sought this information.

The scenario was further compounded by the flight crew of the B737 not hearing the initial communications from the Caravan pilot, or the SFIS controller's response, and the flight crew remained unaware of the Caravan until just prior to it entering the runway. The Caravan pilot did not see the B737 approaching from the opposite direction and took-off directly towards it, resulting in the flight crew of the B737 to conducting a missed approach. No safety alert was issued by the SFIS controller as they were concerned that doing so would result in over transmitting communications from the aircraft in conflict.

The ATSB also found that the SFIS had been implemented in an area with known surveillance coverage limitations, resulting in the SFIS controller having no displayed positional information for the Caravan until it reached an altitude of about 1,500 feet. Consequently, the controller was solely reliant on radio communications for situation awareness during the period of conflict between the Caravan and B737, significantly reducing their ability to provide appropriate traffic and avoidance advice.

What has been done as a result

Although reportedly an outcome of a post‑implementation review, rather than a response to this occurrence, Airservices Australia (Airservices) advised that there was an intention to install additional technology to improve surveillance coverage in the vicinity of Ballina Byron Gateway Airport by March 2023, but that timeline was dependent on a number of factors.

Noting the indefinite timeframe, in order to support Airservices’ intended action, including complying with a related recommendation issued by the Civil Aviation Safety Authority in its Ballina airspace review, the ATSB issued a safety recommendation to Airservices to address this surveillance limitation in a timely manner.

Safety message

Safety around non-controlled airports is an area of focus for the ATSB and a SafetyWatch priority. Pilots can reduce the likelihood of similar incidents occurring by communicating directly with aircraft on the common traffic advisory frequency when services such as a surveillance flight information service are provided. Additionally, pilots and controllers alike should ensure critical information is communicated and understood in order to maintain the accuracy of shared mental models.

The ATSB also strongly encourages the fitment of ADS‑B transmitting, receiving and display devices as they significantly assist the identification and avoidance of conflicting traffic. The continuous positional information that ADS‑B provides can highlight a developing situation many minutes before it becomes hazardous – a significant improvement on both point‑in‑time radio traffic advice and ‘see‑and‑avoid’. The ATSB also notes that ADS‑B receivers, suitable for use on aircraft operating under both the instrument or visual flight rules, are currently available within Australia at low cost and can be used in aircraft without any additional regulatory approval or expense.

The occurrence

On the afternoon of 16 September 2021, a Virgin Australia Airlines Boeing 737-8FE (B737) aircraft, registered VH‑YIO (Figure 1), was conducting a scheduled passenger service from Sydney Airport, New South Wales (NSW), to Ballina Byron Gateway Airport (Ballina Airport), NSW. There were 2 flight crew, 4 cabin crew and 47 passengers on board. The captain was pilot flying (PF) and the first officer (FO) was pilot monitoring (PM).[1]

Figure 1: VH-YIO

Source: Supplied

At 1332:33 Eastern Standard Time,[2] when the B737 was approximately 44 NM to the south of Ballina Airport, the FO made an initial positional broadcast on the Ballina Airport common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF) [3] (see the sections titled Broadcast area and Common traffic advisory frequency). This broadcast was acknowledged by the Ballina surveillance flight information service (SFIS) controller (see the section titled Surveillance flight information service).

At 1335:15, the B737 FO made another broadcast on the Ballina CTAF advising that the aircraft was now 27 NM south of Ballina Airport and would land on runway 24 at an estimated time of 1345.

Meanwhile, the pilot of a Cessna Caravan 208 (Caravan) aircraft, registered VH-YMV prepared for a private instrument flight rules (IFR) flight from Ballina Airport to Sunshine Coast Airport, Queensland. The pilot was the only person on board and the purpose of the flight was to reposition the Caravan to the Sunshine Coast for parachute operations.

The Caravan pilot had flown a different aircraft from Sunshine Coast Airport to Ballina Airport earlier that day. On arrival at Ballina Airport, the pilot undertook a prefight inspection of VH-YMV and readied the aircraft for the flight.

At 1338:00, the B737 FO made a further broadcast on the Ballina CTAF advising that the aircraft was now 15 NM south‑east of Ballina Airport and would be positioned for a 10 NM final to land on runway 24 at a time of 1345.

At 1341:17, the Caravan pilot made a taxi broadcast on the Ballina CTAF advising that the aircraft would depart from runway 06 for an IFR flight to the Sunshine Coast. At the time, the weather recorded by the aerodrome weather information service (AWIS) indicated a few clouds at 2,600 feet above ground level, visibility greater than 10 km and a 12-17 knot wind from a 160-170° direction. The pilot recalled listening to AWIS and noting a crosswind. Although this wind direction favoured a departure from runway 24, the pilot recalled observing the windsock, assessing it favoured a departure from runway 06, and hence electing to do so. The aircraft was parked on the general aviation apron and the pilot chose to take-off from the intersection of taxiway A and runway 06, which involved a short taxi to the hold point with no backtracking along the runway.

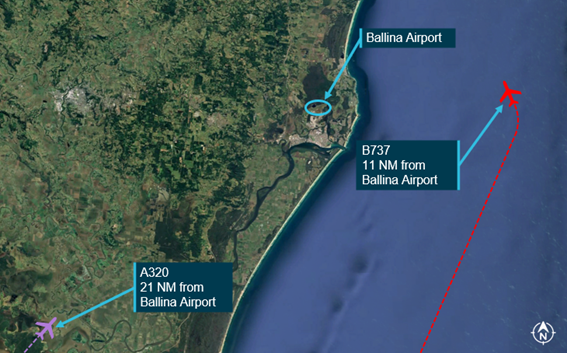

At 1341:27, the SFIS controller responded to the Caravan pilot’s broadcast and provided the pilot with traffic information on the B737 and a Jetstar Airbus A320 (A320), registered VH-VQK, that was also inbound to Ballina Airport (Figure 2). The SFIS controller stated:

Yankee Mike Victor squawk 4547. Traffic [is] Velocity 1141, 737, shortly turning onto a 10 NM final, followed by Jetstar 464 an Airbus 320 currently 20 NM to the south-west and they're tracking for a right downwind runway 24. They'll be crossing centreline at about time four five.

Figure 2: At 1341:51, the pilot of the Caravan advised the SFIS controller that they had copied the traffic and correctly read back the transponder squawk code. Figure 2: A320 and B737 locations at 1341:27

Source: Google Earth, annotated by the ATSB

The flight crew of the B737 did not recall hearing the Caravan pilot’s taxi broadcasts or the SFIS controller’s responses to the taxi broadcast on the CTAF and were unaware of the presence of the Caravan. The SFIS controller noted that the B737 flight crew had not responded to the Caravan pilot’s taxi broadcast but did not confirm if they were aware of the Caravan (see the section titled SFIS procedures).

The B737 continued the approach for Ballina Airport and, at 1341:57, made a left turn onto a 10 NM final for runway 24.

Meanwhile, the Caravan pilot had formed the belief that the B737 would land on runway 06 based on their earlier observation of the runway windsock. The pilot had also misunderstood the traffic information provided by the SFIS controller as meaning that the B737 was on approach for runway 06, not runway 24, and hence believed that the Caravan could depart ahead of the arriving B737 without causing a conflict. The pilot recalled conducting a visual check for traffic before entering the runway but did not see the B737 that was on final approach to land on runway 24 (see the section titled Human factors).

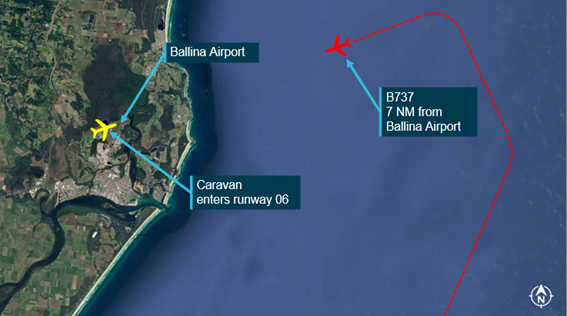

At 1343:28, the pilot of the Caravan made a broadcast on the CTAF stating that the aircraft was entering and rolling runway 06 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Caravan and B737 locations at 1343:28

Source: Google Earth, annotated by the ATSB

The SFIS controller heard the Caravan pilot’s ‘entering and rolling’ broadcast and was aware of the developing conflict between the Caravan and the B737. However, the SFIS controller elected not to issue a safety alert (see section titled Safety alert).

The ‘entering and rolling’ broadcast was the first transmission the flight crew of the B737 recalled hearing from the Caravan pilot and when they first became aware of the Caravan. At 1343:36, the B737’s FO made a broadcast on the CTAF stating that the B737 was on a 5 NM final approach for runway 24. Neither the Caravan pilot nor the SFIS controller responded to this broadcast.

At about 1344:00, the Caravan pilot commenced the take-off directly towards the approaching B737.

At 1344:15, the B737’s FO made a further broadcast on the CTAF querying the Caravan’s location. At 1344:19, the Caravan’s pilot responded stating that the aircraft had just become airborne from runway 06 (Figure 4). The B737’s FO immediately replied asking if the Caravan pilot could see the B737, which was now on a 3 NM final for runway 24. At 1344:36, the Caravan pilot confirmed sighting the B737, and its FO then requested the Caravan pilot to commence a turn. The Caravan pilot did not respond to the FO’s broadcast, but the pilot did initiate a turn to the right shortly after becoming airborne.

Figure 4: Caravan and B737 locations at 1344:19

Source: Google Earth, annotated by the ATSB

At 1345:06, the captain of the B737 initiated a missed approach and, a short time later, the flight crew sighted the Caravan ahead of their aircraft, travelling in a northerly direction. During the missed approach, the flight crew received a traffic collision avoidance system[4] traffic advisory[5] generated by the Caravan’s proximity. The flight crew maintained visual contact with the Caravan and repositioned the B737 for a left circuit to land on runway 24.

Figure 5: Caravan and B737 tracks and relative distances

Source: Google Earth, annotated by the ATSB

The Caravan pilot set course north for Sunshine Coast Airport and communications with the aircraft were transferred to the Brisbane Airport approach controller at 1349:26. The B737 landed at Ballina Airport at about 1359:00.

Context

Personnel information

B737 flight crew

The captain held an air transport pilot licence (ATPL) (aeroplane) and had a total flying time of 15,719 hours, having flown 25 hours in the previous 90 days. The captain was familiar with Ballina Airport and had operated there in both turboprop and jet aircraft over a 20-year period.

The FO held an ATPL (aeroplane) and a total flying time of 8,607 hours, having flown 72.3 hours in the previous 90 days. The FO was also familiar with Ballina Airport having operated there in both turboprop and jet aircraft throughout their career. The FO’s last flight to Ballina Airport took place on 11 May 2021.

Caravan pilot

The pilot held a commercial pilot licence (aeroplane) and a total flying time of 1,008 hours, having flown 50 hours in the previous 90 days. The pilot was familiar with Ballina Airport and had last flown into the airport approximately 3 months prior to the incident flight.

Controller

The surveillance flight information service (SFIS) controller had experience in both tower and en route air traffic environments prior to commencing in the SFIS controller role. The controller was based in the Airservices Australia Brisbane Centre and had undertaken SFIS endorsement training in August 2021, before the SFIS service commenced on 12 August.

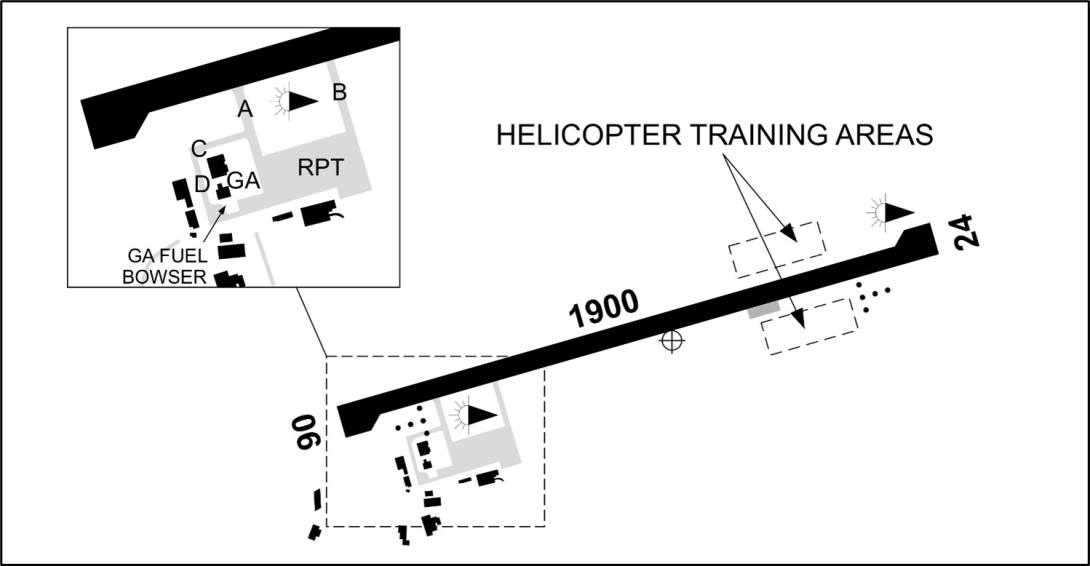

Ballina Byron Gateway Airport

Ballina Byron Gateway Airport is situated approximately 3 NM from the city of Ballina, NSW. The airport has an elevation of 7 feet above mean sea level (AMSL) and a single sealed runway, orientated in a 062°-242° magnetic direction (Figure 6). The airport had global positioning system (GPS)‑based instrument approaches and a non-directional beacon ground-based navigation aid.

Figure 6: Ballina Byron Gateway Airport

Airspace and traffic services

Ballina Airport was located within non‑controlled Class G airspace, which extended from the ground surface to 8,500 feet AMSL. The airport did not have a control tower and was not supported by an air traffic control separation or sequencing service (that is, a non-controlled airport).

Overlying the non‑controlled airspace was Class C controlled airspace which extended up to flight level (FL) 180,[6] and controlled Class A airspace above that. An air traffic information and separation service was provided within the Class C airspace and a separation service was provided within the Class A airspace. A restricted area existed approximately 5 NM south of the airport (the aircraft involved in this incident were clear of this area).[7]

The non‑controlled airspace surrounding Ballina Airport was available for use by aircraft operating under visual flight rules and instrument flight rules. The primary method of traffic separation at Ballina Airport was visual and relied on pilots using ‘alerted see-and-avoid’[8] practices.

A broadcast area (BA) was in place within an approximate radius of 15 NM from the airport and a surveillance flight information service (SFIS) was provided to aircraft operating within the BA during defined periods (see the section titled Surveillance flight information service).

Broadcast area

Surrounding Ballina Airport was a BA that mandated the carriage and use of radio equipment for aircraft operating within a radius of 15 NM of the airport, from surface level to 8,500 feet, excluding penetrating arcs of circles for Lismore Airport and Gold Coast control area steps (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Ballina Airport broadcast area

Source: Google Earth, annotated by the ATSB

The broadcast area was expanded from 10 NM to 15 NM on 28 January 2021 to ‘reduce residual airspace risk’. The expansion of the BA occurred following a separation incident involving a Jetstar A320 and a Jabiru aircraft that occurred about 13 NM from Ballina Airport on 28 November 2020 (see ATSB investigation AO-2020-062).

The broadcast area required all pilots to make mandatory positional broadcasts when entering or operating within the defined lateral and vertical limits of the BA on the Ballina Airport CTAF. Pilots were also required to acknowledge calls from aircraft departing or landing whose operations were in conflict with their own, and should announce when in receipt of a call indicating that their aircraft may be in conflict when operating outside of the circuit area.

Common traffic advisory frequency

The Ballina Airport CTAF was a designated radio frequency on which pilots made positional broadcasts when operating in the vicinity of the airport. The Ballina Airport CTAF was shared with neighbouring airports and aeroplane landing areas at Casino, Lismore and Evans Head.

A surveillance flight information service, detailed in the following section, was provided on the CTAF to aircraft operating within the Ballina Airport BA.

Surveillance flight information service

A surveillance flight information service (SFIS) was provided to aircraft operating within the Ballina Airport BA between 2200-0800 Coordinated Universal Time [9] (1 hour earlier during Eastern Daylight-saving Time[10]) or as notified by notice to airmen.

The SFIS utilised available surveillance data, and broadcasts on the airport’s CTAF, to provide all visual flight rules (VFR) and instrument flight rules (IFR) aircraft with a full traffic information and alerting service. The information provided by the SFIS controller contained advice on conflicting traffic. However, the SFIS was not a separation or sequencing service and pilots remained responsible for seeing and avoiding other aircraft.

The service was provided by a dedicated Airservices Australia air traffic controller located at the Brisbane Centre. Pilots made broadcasts and reported to the SFIS controller (callsign ‘Ballina Information’) on the Ballina Airport CTAF.

The SFIS commenced on 12 August 2021 and replaced the previously established certified air/ground radio service (CA/GRS). The CA/GRS was provided at Ballina Airport from March 2017 to the commencement of the SFIS service in August 2021 and was delivered by a certified air/ground radio operator (CA/GRO) located at the airport.

SFIS procedures

Airservices Australia procedures required the SFIS controller to communicate specific details when passing traffic information to aircraft. This information was to include the traffic’s intentions, the traffic’s reported position and estimate. The SFIS controller was also procedurally required to provide traffic information to aircraft in class G airspace when an aircraft was expected to arrive with less than 10 minutes separation time from aircraft departing from the same airport.

During this occurrence, the SFIS controller provided traffic information to the Caravan pilot that did not include the B737’s estimated landing time and runway number. The controller stated that as the pilot’s communications appeared to be ‘competent’ and ‘confident’, it had not been considered necessary to emphasise the B737’s landing direction. Similarly, when the B737’s flight crew did not respond to the Caravan pilot’s taxi broadcast, the controller did not consider it necessary to confirm they were aware of the Caravan because, according to their SFIS training, they were not required to follow-up communications for aircraft already on the CTAF (as was the case for the B737).

Safety alert

A safety alert comprises advice provided to a pilot when the SFIS controller becomes aware that an aircraft is in a position that places it in unsafe proximity to terrain, obstructions, active restricted or prohibited areas, or another aircraft. In cases where an aircraft is in close proximity to another, a safety alert should be issued by the controller unless the pilot had advised that action to resolve the situation was being taken, or the other aircraft was in sight. A safety alert could be issued in all classes of airspace both within and outside surveillance coverage.

However, on the day of the occurrence, the SFIS controller did not issue a safety alert to either the B737 or the Caravan after its pilot reported entering and rolling runway 06 although it was apparent to the controller that a conflict would result. The controller advised that their reason for not doing so was due to a concern that the alert could result in the over transmission of radio communications from either aircraft.

Technical systems

Secondary surveillance radar

Secondary surveillance radar utilises ground stations (interrogators) and transponders on board aircraft.

A transponder is a receiver/transmitter which transmits an automatic reply upon receiving an interrogation request. A manual ‘ident’ transmission can also be initiated by the pilot. The information that may be transmitted by a transponder is dependent on the ‘mode’ of equipment fitted to an aircraft:

- Mode A transponders transmit an identifying code only

- Mode C transponders transmit an identifying code and altitude (based on standard pressure)

- Mode S transponders transmit an identifying code, altitude (based on standard pressure) and permit data exchange

The signal from the transponder is received by the ground station and combined with the aircraft’s position established via radar (range and bearing). This information is then relayed to air traffic control where it is displayed on the controller’s console screen.

Automatic dependant surveillance broadcast

Automatic dependent surveillance broadcast (ADS-B) utilises electronic equipment on board an aircraft to automatically broadcast the aircraft’s precise location, and other parameters, via digital data link (ADS-B OUT). The data is then used by air traffic control and other aircraft to depict the aircraft’s position, and other information, on a display without the need for radar.

The system uses GPS data to determine the aircraft’s position then transmits the position, and other parameters (such as identity, altitude and speed), at rapid intervals. These transmissions are received by dedicated ADS-B ground stations and the information is then relayed to air traffic control and displayed on the controller’s console screen.

The transmissions can also be received by other aircraft with the capability to receive and displayed this information (ADS-B IN). Both the B737 and Caravan were fitted with ADS-B OUT equipment. Neither aircraft was fitted with ADS-B IN equipment, nor were they required to be.

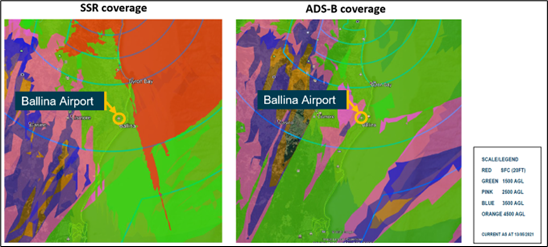

Surveillance coverage

Documents developed by Airservices Australia before implementing the Ballina Airport SFIS contained a list of ‘critical components’ necessary for the service. Although ‘adequate surveillance coverage’ was one of these critical components, Ballina Airport had no ADS-B ground station and the surrounding area had significant limitations in SSR and ADS-B coverage. Surveillance coverage charts produced by Airservices Australia indicated that, near the airport, the SSR and ADS-B coverage did not commence until about 1,500 feet above ground level (Figure 8).

Figure 8: SSR and ADS-B coverage within the vicinity of Ballina Airport

Source: Airservices Australia, annotated by the ATSB

The hazards and risks associated with the surveillance coverage limitations were identified by Airservices Australia prior to the implementation of the SFIS and documented as:

Limited surveillance coverage may lead to unintended aircraft proximity (Airprox), inadequate separation assurance (ISA), or loss of separation (LOS) occurrence.

Airservices Australia conducted a risk assessment and rated the initial risk as moderate. However, its pre-implementation risk treatment did not reduce the risk any further. Residual risks associated with the surveillance coverage limitations were formally accepted and the SFIS was implemented with the risks unaddressed. These limitations meant the Caravan’s positional information was not displayed on the SFIS controller’s console screen until it reached an altitude of about 1,500 feet, which occurred about 100 seconds after take-off was commenced.

Previous events

A search of the ATSB occurrence database found that during the period from the implementation of the SFIS (12 August 2021) to the date of the incident (16 September 2021), there was one reported occurrence and no reported separation issues within 20 NM of Ballina Airport.

Regulatory oversight

The Airspace Act 2007 assigned the administration and regulation of Australian administered airspace to the Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA). As part of this function, CASA was required to undertake regular reviews of airspace to determine if existing classifications were appropriate, air navigation services and facilities were suitable, there was safe, efficient, and equitable use of airspace, and identify any associated risk factors.

On 15 December 2022, CASA publicly released a final Ballina airspace review. The review identified 3 areas of concern:

- Frequency congestion

- Heightened risk of separation incidents

- Situational awareness

As a result, the review made 9 recommendations (Table 1).

Table 1: Ballina airspace review recommendations

| No. | Recommendation |

| 1 | CASA should prepare a Request For Change (RFC) to separate the Lismore and Casino Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF) from the Ballina CTAF by 16 June 2022. |

| 2 | Evans Head Airport should be allocated the common CTAF (126.7 MHz) by 16 June 2022. |

| 3 | CASA should direct AA to install an Automatic Dependent Surveillance - Broadcast (ADS-B) ground station in the vicinity of Ballina to improve surveillance as soon as practicable but no later than April 2023. The ground station should, as far as is practical, provide ADS-B surveillance capability to the runway surface. |

| 4 | CASA should explore a suitable regulatory framework that can safely authorise sport and recreational aircraft and pilot certificate holders to operate in the controlled airspace associated with Ballina where pilot certificate holders meet CASA specified competency standards and the aircraft are appropriately equipped. |

| 5 |

CASA’s Stakeholder Engagement Division (SED) should conduct additional safety promotion programs in relation to Ballina operations as soon as practicable. The programs should include, but are not limited to the following key elements: a. reinforce the mandatory radio calls required when operating within the Ballina MBA in the interim, pending the establishment of controlled airspace, and b. later, provide guidance as to how a Sport Aviation Body might develop a suitable scheme and make application to CASA for approval, under the regulatory framework identified in recommendation 4. |

| 6 | Uncertified aerodromes and flight training areas around Ballina should be promulgated in aeronautical publications to increase pilot situational awareness. |

| 7 | As an interim action pending the completion of Recommendation 8, CASA should make a determination to establish a control area around Ballina Byron Gateway Airport with a base which is as low as possible, and direct AA to provide services within the control area. The services should be provided during all periods of scheduled Air Transport Operations and include an Approach Control Service to aircraft operating under the Instrument Flight Rules (IFR), separation between IFR aircraft, VFR traffic information to all aircraft, and sequencing of all aircraft to and from the runway. CASA and AA should jointly explore opportunities to detect non-cooperative aircraft or vehicles in the immediate vicinity of the runway. The services should be established as soon as practicable but no later than 30 November 2023. |

| 8 | CASA should make a determination that Ballina Byron Gateway Airport will become a controlled aerodrome with an associated control zone and control area, and direct Airservices Australia (AA) to provide an Aerodrome Control Service1 to the aerodrome. That service should be established as soon as practicable but no later than 13 June 2024. |

| 9 | CASA should prepare and finalise an Airspace Change Proposal (ACP) for a control zone and control area steps in preparation for the implementation of Recommendations 7 and 8. |

Source: Airspace Review of Ballina – 2022 with minor amendments by the ATSB

On 16 June 2022, recommendation 1 and 2 were implemented resulting in Lismore, Casino and Evans Head being separated from the Ballina Airport CTAF. Recommendation 3 was due for implementation by April 2023 and proposed the installation of an ADS-B ground station in the vicinity of Ballina Airport to provide surveillance coverage to the runway surface.

The ATSB undertook a detailed assessment of CASA’s role in the oversight of the airspace surrounding Ballina Airport following a separation occurrence involving an Airbus A320-232 and a Jabiru that took place on 28 November 2020 (see investigation AO-2020-062).

Human factors

The ATSB investigation considered a range of human factors that could have influenced the decisions and actions of the pilots and controller involved. No indicators that increased the risk of any of the individuals experiencing a level of fatigue known to influence performance were found. The following factors, however, were found to have possibly had an influence:

- shared mental models

- situation awareness

- confirmation bias

Mental models

According to Methieu et al (2000), mental models are internally organised knowledge structures that allow individuals to understand and interact with their environment. Mental models are said to be ‘shared’ when the models of individuals overlap – the greater the overlap the greater the similarity of understanding.

In scenarios involving the movement of aircraft within the airspace system, it is anticipated that pilots and air traffic controllers will have a high degree of shared mental model overlap. However, when communication is ineffective, and critical information and assumptions are not shared, the degree of shared mental model overlap is decreased, coordinated decision making is degraded, and safety defences are eroded (Bearman et al 2010).

The mismatch of mental models was evident in the lead up to this incident. Critical traffic information and assumptions were not shared between the SFIS controller, the Caravan pilot, and the B737 flight crew. This resulted in each party holding a different mental model of the traffic scenario.

Situation awareness

Situation awareness (SA) is best conceptualised as a 3-stage process:

- task related features or cues are acquired and interpreted by the individual

- information is integrated and comprehended within the context of the task to derive meaning for the individual

- the individual anticipates the future state of the system (Wiggins 2022)

The accuracy of an individual’s SA directly influences their decisions.

The SFIS controller, the Caravan pilot and the B737 flight crew all held incomplete information on the traffic scenario and the intended actions of the others involved. As a result, their capacity to accurately predict the future traffic state was compromised and their decision-making impacted accordingly.

Confirmation bias

Confirmation bias involves an individual seeking out information that confirms an assumption and rejecting, ignoring, or explaining away information that conflicts with the held assumption (Wiggins 2022). Based primarily on their assessment of the windsock, the Caravan’s pilot incorrectly believed that the B737 was on final approach for runway 06 and not runway 24. It is therefore possible that the pilot’s confirmation bias influenced the visual check before entering the runway with the B737 on final approach from the opposite direction going undetected.

Safety analysis

The incident

On 16 September 2021, a Boeing 737, VH-YIO (B737), was approaching runway 24 to land at Ballina Byron Gateway Airport when a Cessna Caravan 208, VH-YMV (Caravan), commenced a take-off on the reciprocal runway. The B737’s flight crew conducted a missed approach during which the lateral separation between the 2 aircraft decreased to approximately 0.9 NM with vertical separation reducing to about 700 feet. At the time of the incident, the aircraft were operating within the airport’s broadcast area, and both were receiving the associated surveillance flight information service (SFIS).

Communications

The SFIS controller had not included the B737’s estimated time of landing and runway direction when providing traffic information to the Caravan pilot. In addition, the Caravan pilot had formed the belief that the B737 would land on runway 06 (based on observing the runway windsock), and then interpreted the traffic information provided by the controller incorrectly as it confirmed their incorrect mental model. The pilot did not seek to validate this assumption by communicating directly with the B737’s flight crew or by querying the information provided by the controller.

The scenario was further compounded by the B737’s flight crew not hearing the Caravan’s taxi broadcasts or the SFIS controller’s responses. Those taxi transmissions commenced 40 seconds before the B737 turned onto final approach for runway 24. The ATSB was not able to determine why the flight crew did not hear the exchange. In any case, they were not aware of the Caravan until the ‘entering and rolling’ broadcast made by its pilot.

The SFIS controller knew the B737’s flight crew had not acknowledged the Caravan pilot’s taxi broadcast but recalled from SFIS training that follow-up communications were not necessary for aircraft already on the common traffic advisory frequency (CTAF). Consequently, the controller decided not to confirm that the flight crew were aware of the Caravan, and an opportunity to address the evolving situation was missed. This resulted in the B737’s flight crew remaining unaware of the Caravan and the latter’s pilot continued to incorrectly believe the B737 would land in the opposite direction.

The Caravan pilot’s incorrect mental model also led them to believe the Caravan could take-off ahead of the landing B737, using runway 06, without any conflict. The pilot recalled conducting a visual check prior to entering the runway; however, their likely confirmation bias and reduced situation awareness possibly resulted in not sighting the approaching B737. Consequently, the Caravan was taxied onto the runway and a take-off commenced directly towards the B737.

Safety alert

The SFIS controller recognised the impending conflict between the two aircraft after hearing the Caravan pilot’s ‘entering and rolling’ broadcast but decided not to issue a safety alert because of concerns of over transmitting communications from the Caravan or the B737. However, between the ‘entering and rolling’ broadcast and confirmation that the Caravan pilot had sighted the B737, there was a total of 53 seconds during which time no transmissions were made on the CTAF. A safety alert issued during this time would probably have ensured the pilots on both aircraft were fully aware of the conflict.

Surveillance coverage limitations

The limitation in coverage resulted in the SFIS controller having no positional information on the Caravan during the period of conflict until the aircraft reached an altitude of about 1,500 feet about 100 seconds after taking off. During this period, the controller was solely reliant on radio communications for situation awareness and had reduced options for providing any avoidance advice necessitated by the situation.

The heightened risk of separation incidents in the vicinity of Ballina Airport was identified in the Civil Aviation Safety Authority’s (CASA’s) Ballina airspace review, which was published in December 2022. Recommendations contained in that review document included the installation of an automatic dependent surveillance broadcast (ADS-B) ground station in the vicinity of Ballina Airport to enable ADS-B surveillance capability to the runway surface. The review document contained 8 other recommendations designed to incrementally transition Ballina Airport to a controlled aerodrome service with an associated control zone and control area steps by 13 June 2024. Such an aerodrome control service would have prevented the traffic conflict between the B737 and the Caravan.

Both this separation occurrence and that detailed in AO-2020-062 involved high-capacity transport aircraft using the primary defence of alerted see‑and‑avoid. Noting the known limitations of this principle, and the increasing and complex mix of traffic, the ATSB considers that timely implementation of the recommendations detailed in CASA’s airspace review document would significantly improve safety at Ballina Airport.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition, ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. Safety issues are highlighted in bold to emphasise their importance. A safety issue is a safety factor that (a) can reasonably be regarded as having the potential to adversely affect the safety of future operations, and (b) is a characteristic of an organisation or a system, rather than a characteristic of a specific individual, or characteristic of an operating environment at a specific point in time. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the separation occurrence involving Boeing 737-8FE, VH-YIO (B737) and Cessna Caravan 208, VH-YMV (Caravan) at Ballina Byron Gateway Airport, New South Wales on 16 September 2021.

Contributing factors

- Based on an assessment of the windsock only, the Caravan pilot wrongly assumed that the B737 would land behind them on runway 06 and not present a conflict for their departure. This incorrect mental model of the traffic was not corrected prior to the conflict as the surveillance flight information service controller did not specify that the B737 would land on runway 24 and the pilot did not confirm the runway direction with the controller or with the B737’s flight crew.

- The B737’s flight crew did not hear the Caravan pilot’s taxi broadcast or the surveillance flight information service controller's response, who also did not confirm if the flight crew were aware of the Caravan. Consequently, the flight crew was unaware of the Caravan until its pilot made a broadcast before entering the runway.

- The visual check by the Caravan’s pilot before entering the runway did not identify the B737 on final approach to land on runway 24, possibly due to confirmation bias and degraded situation awareness resulting from the pilot’s incorrect mental model of the traffic.

- The Caravan’s pilot commenced a take-off directly towards the approaching B737 resulting in its flight crew conducting a missed approach to avoid the Caravan.

Other factors that increased risk

- The surveillance flight information service controller did not issue a safety alert after the Caravan entered the runway and commenced taking off towards the approaching B737 due to concerns that issuing an alert would result in over transmitting communications from either aircraft.

- The surveillance flight information service (SFIS) had been implemented in an area with known surveillance coverage limitations, resulting in the SFIS controller having no displayed positional information for the Caravan until it reached an altitude of about 1,500 feet. Therefore, during the period of conflict between the Caravan and B737, the controller was solely reliant on radio communications for situation awareness, reducing their ability to provide appropriate traffic and avoidance advice. (Safety issue)

Safety issues and actions

|

Depending on the level of risk of a safety issue, the extent of corrective action taken by the relevant organisation(s), or the desirability of directing a broad safety message to the aviation industry, the ATSB may issue a formal safety recommendation or safety advisory notice as part of the final report. All of the directly involved parties are invited to provide submissions to this draft report. As part of that process, each organisation is asked to communicate what safety actions, if any, they have carried out or are planning to carry out in relation to each safety issue relevant to their organisation. Descriptions of each safety issue, and any associated safety recommendations, are detailed below. Click the link to read the full safety issue description, including the issue status and any safety action/s taken. Safety issues and actions are updated on this website when safety issue owners provide further information concerning the implementation of safety action. |

SFIS surveillance coverage

Safety issue number: AO-2021-038-SI-01

Safety issue description: The surveillance flight information service (SFIS) had been implemented in an area with known surveillance coverage limitations, resulting in the SFIS controller having no displayed positional information for the Caravan until it reached an altitude of about 1,500 feet. Therefore, during the period of conflict between the Caravan and B737, the controller was solely reliant on radio communications for situation awareness, reducing their ability to provide appropriate traffic and avoidance advice.

Glossary

ADS-B Automatic dependant surveillance broadcast

AMSL Above mean sea level

ATPL Air transport pilot licence

BA Broadcast area

CA/GRO Certified air/ground radio operator

CA/GRS Certified air/ground radio service

CTAF Common traffic advisory frequency

FO First officer

GPS Global positioning systems

IFR Instrument flight rules

KM Kilometres

NM Nautical miles

NSW New South Wales

PF Pilot flying

PM Pilot monitoring

SA Situation awareness

SFIS Surveillance flight information service

SSR Secondary surveillance radar

VFR Visual flight rules

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- the flight crew of VH-YIO and pilot of VH-YMV

- the SFIS controller

- Virgin Airlines Australia

- Avdata

- OzRunways

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority

- Airservices Australia

- Bureau of Meteorology

- Experience Co Limited

References

Bearman C, Paletz S, Orasanu J & Thomas M 2010, The breakdown of coordinated decision making in distributed systems, Human factors, Vol. 52, pp. 173-188

Mathieu J, Heffner T, Goodwin G, Salas E & Cannon-Bowers J 2000, The influence of shared mental models on team process and performance, Journal of applied psychology, vol 85, pp. 273

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- the flight crew of VH-YIO and pilot of VH-YMV

- the SFIS controller

- Virgin Airlines Australia

- Airservices Australia

- Experience Co Limited

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority.

Submissions were received from:

- Airservices Australia

- Experience Co Limited

- Civil Aviation Safety Authority.

The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2023

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] Pilot Flying (PF) and Pilot Monitoring (PM): procedurally assigned roles with specifically assigned duties at specific stages of a flight. The PF does most of the flying, except in defined circumstances; such as planning for descent, approach and landing. The PM carries out support duties and monitors the PF’s actions and the aircraft’s flight path.

[2] Eastern Standard Time (EST): Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) +10 hours.

[3] A common traffic advisory frequency is a designated frequency on which pilots make positional broadcasts when operating in the vicinity of a non-controlled airport, or within a broadcast area.

[4] A traffic collision avoidance system (TCAS) interrogates the transponders of nearby aircraft and uses this information to calculate the relative range and altitude of this traffic. The system provides a visual representation of this information to the flight crew as well as issuing alerts should a traffic issue be identified.

[5] A traffic advisory (TA) is an alert issued when the detected traffic may result in a conflict (the closest point of separation is about 40 seconds away on the current projected flight paths). Pilots are expected to initiate a visual search for the traffic causing the TA.

[6] Flight level: at altitudes above 10,000 ft in Australia, an aircraft’s height above mean sea level is referred to as a flight level (FL). FL 180 equates to 18,000 ft.

[7] The restricted area was activated by a notice to airmen when military jet aircraft were operating within the area and/or live-firing exercises were taking place.

[8] Pilots are responsible for sighting conflicting traffic, and avoiding a collision, having been alerted to the presence of

traffic in their immediate vicinity. This is principally achieved via radio communications.

[9] Coordinated Universal Time (UTC): the time zone used for aviation. Local time zones around the world can be expressed as positive or negative offsets from UTC.

[10] Eastern Daylight-saving Time (EDT): Universal Coordinated Time (UTC) +11 hours.