Executive summary

What happened

On 17 September 2021, intermodal freight train 8796, operated by Aurizon, was en route from the Stuart terminal (near Townsville) to Brisbane, Queensland. One of the wagons was loaded with a flat rack carrying a heavy road vehicle tipping trailer that was out of gauge (over the permissible height for the route).

During the journey, the trailer’s hydraulic lifting post collided with the overhead structure of Alexandra Bridge in Rockhampton, causing damage to the bridge and trailer. There were no injuries and no damage to the train.

What the ATSB found

The Stuart terminal was an intermodal freight facility that was cooperatively operated between Linfox and Aurizon. Linfox was responsible for the movement of road freight to and from the terminal, and owned the wagons. Aurizon conducted the loading of rail wagons at the terminal and was responsible for rail operations and rail safety, including the safety and integrity of loads.

The tipping trailer was a Linfox asset rather than customer freight. As such, it was not managed through Linfox’s normal process, which required any non-standard loads to be referred to management for approval. The Linfox capacity officer who entered the load into the freight management system was not advised that the trailer was a tipping trailer and, as a result, it was entered into the system with generic, incorrect dimensions and with no indication of it being potentially out-of-gauge. In addition, unlike at other terminals where Linfox was directly involved in loading trains, Linfox did not have a process for internal, non-standard freight movements at the Stuart terminal to be reviewed and approved for conformance to the permissible loading profile for transport via rail.

The tipping trailer was secured onto a flat rack by Linfox staff, and then lifted onto the wagon by an Aurizon heavy lift operator. The heavy lift operator misjudged the height of the freight when loading the wagon, likely associated with the heavy lift operator not having any nearby reference objects and having a high level of expectancy that the load would not be out of gauge (given that non-standard loads were rarely encountered and there had been no prior indication that this load would be out of gauge).

Later, while conducting a walking inspection of the completed consist, the heavy lift operator did not detect the over-height load, probably due to expectancy and being focussed on checking that the loads were secure rather than their height. Similarly, the out-of-gauge load was not detected during 2 subsequent roll-by inspections (one at Stuart and one at Merinda).

At the Stuart terminal, Aurizon did not routinely apply a process to verify that the dimensions of non-standard loads were within the permissible loading profile. Aurizon had previously had a tool for measuring the height of loads at the terminal. However, at the time of the occurrence, it did not have any measuring equipment available to identify freight loads that were outside the permissible loading profile for transport via rail.

What has been done as a result

Aurizon reported that it carried out a range of safety actions as a result of this occurrence, including:

- installing a passive over-height warning device (jangle bar) as temporary corrective action, and initiating assessment in relation to automated controls

- updating its freight management system and booking system and implementing procedures for the identification of non-standard freight

- revising competency assessments for forklift and reach stacker operators

- reviewing its loading and securing training and standards.

Linfox advised that it would train forklift and operations staff in Aurizon loading and securing and produce a quick reference guide for loaders, and it arranged for non-standard items to be referred to and approved by the capacity and rail network manager.

Safety message

In the absence of measuring equipment, or nearby objects of a known and relevant height, it is difficult to accurately estimate the dimensions of loaded freight, especially when judging the height of tall freight from ground level. Tools to alleviate this limitation will be significantly more accurate and come with minimal cost and should be available to personnel involved in loading non-standard loads.

The occurrence

Freight arrangements

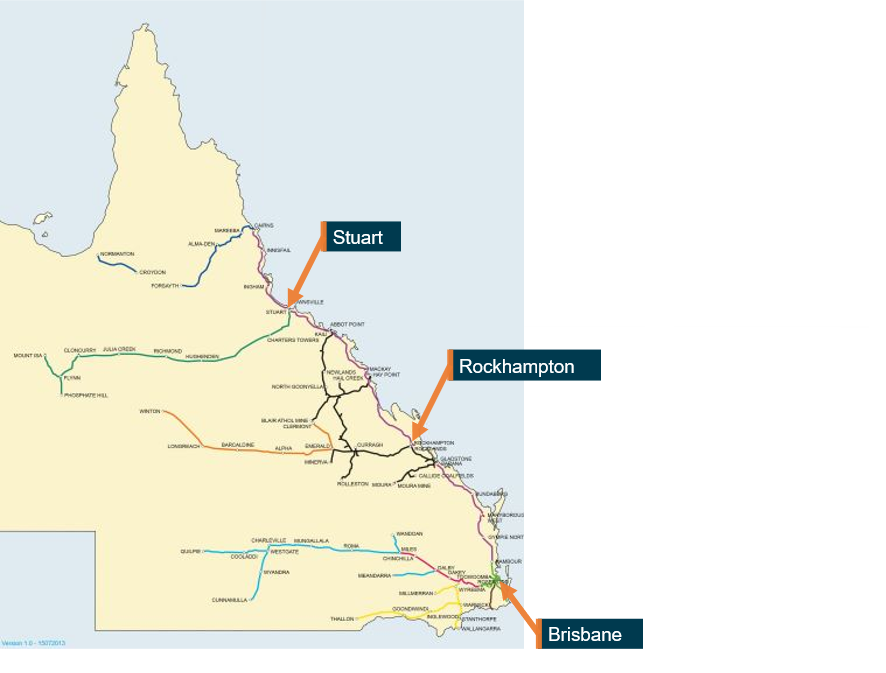

Intermodal freight train 8796, operated by Aurizon, was a regular service between Stuart (near Townsville) to Acacia Ridge (in Brisbane), Queensland on the North Coast Line (Figure 1). At the Stuart terminal, Aurizon was responsible for the loading of freight onto wagons and Linfox was responsible for the movement of road freight to and from the terminal. Queensland Rail (QR) was the rail infrastructure manager for most of the North Coast Line.

Figure 1: Shipping route

Source: Queensland Rail, annotated by ATSB

On 15 September 2021, the Linfox warehouse supervisor at the Stuart terminal made a request (via phone) to a Linfox capacity officer at Acacia Ridge for a (heavy road vehicle) trailer to be transported via rail from Stuart to Brisbane.

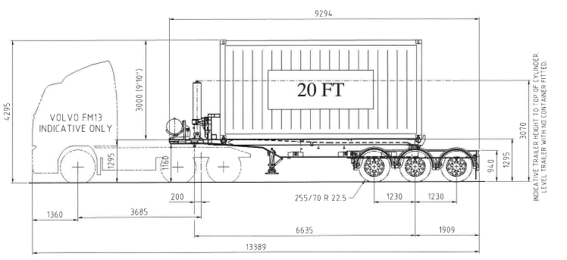

The trailer was a tipping skeletal trailer (Figure 2) that was designed to be towed by a prime mover for transporting shipping containers via road, with the capability of raising one end to unload its contents. It had an incorporated hydraulic lifting post to facilitate the tipping process. The height of the tipping trailer, including the hydraulic lifting post, was 3.070 m. The trailer was a Linfox asset based at the Stuart terminal and it was being transported to be used by Linfox at the Acacia Ridge terminal.

Figure 2: Tipping skeletal trailer dimensions

All measurements are in mm. Shown attached to a prime mover and loaded with a 20-foot container.

Source: Aurizon

The Linfox capacity officer entered the trailer into Aurizon’s A2B freight management system for rail transport. It was entered in the system as a flat rack unit,[1] with a length of 12.192 m and height of 2.743 m, which was the default height in the A2B system. It was classified as ‘general domestic’ freight.

The flat rack type used for the trailer was common to the freight operation, and it had a height 0.260 m. The total height above the wagon floor of the tipping trailer’s hydraulic lifting post on a flat rack was therefore 3.330 m. This was 0.590 m above the maximum permissible height of a load on the QR network.

In their conversation with the capacity officer, the Linfox supervisor did not describe the trailer as a tipping trailer and did not provide (and was not asked to provide) its dimensions. The capacity officer later stated that they were aware that the tipping version of the trailer was probably out of gauge,[2] but they had not been advised that this particular trailer was the tipping version. Accordingly, they thought they were arranging to transport a normal (non-tipping) trailer. They did not change the default dimensions of the load in the freight management system and the consignment note did not include an out-of-gauge warning or indication.

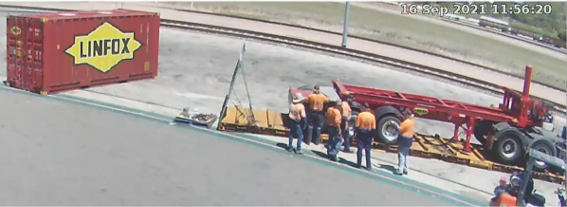

Loading and departure

At about 1150 local time on 16 September, Linfox personnel reversed the trailer with a prime mover onto a flat rack at the Stuart terminal and secured it for transport. A closed-circuit television (CCTV) recording showed that several Linfox personnel were involved in the loading process (Figure 3). The dimensions of the loaded flat rack were not measured during this process.

Figure 3: Loading and securing the tipping trailer on to a flat rack at Stuart Yard

Source: Aurizon

After the trailer was secured onto the flat rack, the Linfox supervisor notified an Aurizon heavy lift (forklift) operator that the trailer was ready to be loaded. At 1347, the heavy lift operator lifted the flat rack with the tipping trailer by forklift onto a flat rail wagon (number BCZY 46459). The load’s dimensions were not verified, and the heavy lift operator did not identify that the load was potentially out of gauge.

The wagons were then shunted onto the train. From 1740 to 1805, the heavy lift operator completed a test and inspection of the completed rail consist, including the wagon with the loaded trailer, checking for container and load security. The inspection was from an area beside the track with eye height below the top of the trailer. They did not identify that the load was potentially out of gauge during this process.

At 1912, train 8796 departed the Stuart terminal as a driver-only operation with a 2800 class locomotive. During the departure of the train, a roll-by inspection[3] was conducted by Aurizon personnel, which did not identify the over-height wagon.

At 2240, additional wagons were added at Merinda. A roll-by inspection at that location did not identify any problems.

A driver crew change occurred at Mackay and the train departed Mackay at 0225 on 17 September. On this section of the journey it had 26 container wagons and was 526 m long with a total weight of 1,164 t, and the consist was predominantly containerised freight and empty flat-bed wagons. The wagon carrying the trailer was the 23rd wagon.

Collision with Alexandra Bridge

At about 0723 on 17 September, the train entered the Alexandra Bridge structure, just outside of Rockhampton Yard, travelling at approximately 25 km/h. The Alexandra Bridge is a concrete pillar and steel truss bridge over a river located in the centre of Rockhampton, serviced by a single rail line and a pedestrian pathway.

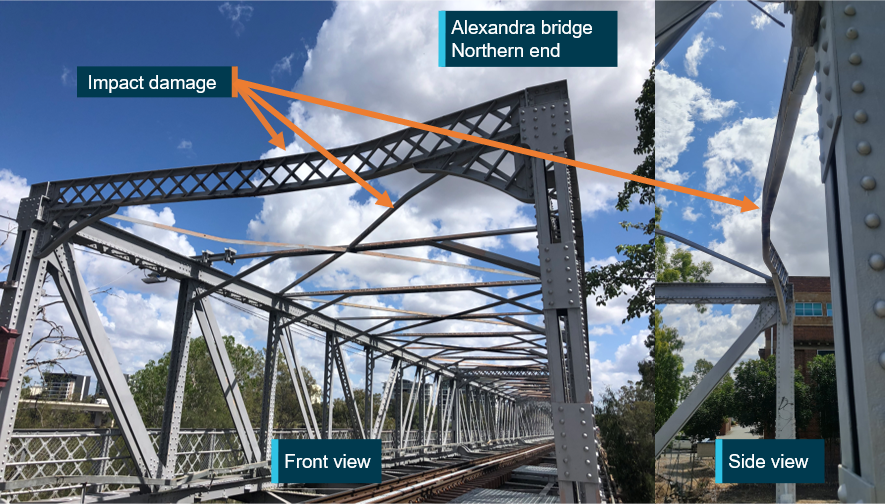

Approximately 2 minutes later, the hydraulic lifting post on the trailer impacted the entry crossbeam of the bridge as its wagon passed onto the bridge (Figure 4). A CCTV recording showed the impact with the crossbeam at the northern end of the bridge causing damage to the girder and buckling of bridge braces. Additionally, the bracing rails on the trailer bent under the impact, forcing the hydraulic lifting post to bend backwards. This gave the trailer clearance under the bridge structure for the rest of its journey across the bridge.

Train 8796 continued to Rockhampton, with the driver unaware that the collision had occurred. At 0734 the train entered Rockhampton Yard.

Figure 4: Trailer collision with bridge

Source: Rockhampton Regional Council

Identification of the damaged trailer

The damaged tipping trailer was observed at Rockhampton Yard (Figure 5). The wagon was removed from the consist and QR was notified of the damage at about 1020.

At 1230, the rail traffic crew of Aurizon train 8798 reported damage to the overhead structure on Alexandra Bridge. QR track workers conducted an inspection of the rail corridor between Stuart and Rockhampton, and they determined that only Alexandra Bridge had been damaged (Figure 6). Rockhampton Regional Council confirmed the impact of the bridge through the review of a CCTV recording.

The bridge was deemed fit for the return of services by QR engineering personnel and reopened to rail traffic at 1530 on 17 September with a 10 km/h speed restriction, pending further assessment.

Figure 5: Damaged skeleton tipping trailer, Rockhampton Yard

Source: Aurizon (upper), Linfox (lower), annotated by the ATSB

Figure 6: Alexandra Bridge girder damage

Source: Queensland Rail, annotated by the ATSB

Context

Track and network information

The North Coast Line consists of 1,680 km of railway between Cairns and Brisbane. Queensland Rail (QR) was the rail infrastructure manager for about 1,567 km, including the section from Townsville to Rockhampton.

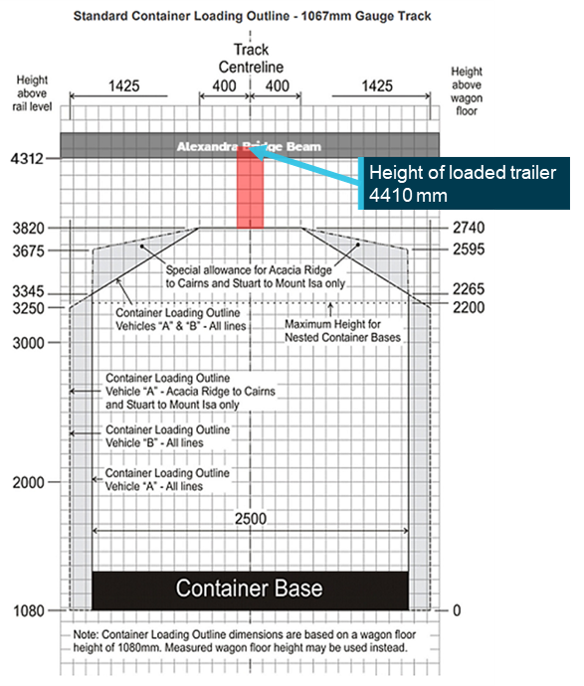

The maximum permissible load height on the on the North Coast Line from Townsville to Brisbane was 3.820 m above the rail, or 2.740 m above the wagon floor with a standard 1.080-m high wagon. Therefore, with a total height of 4.410 m, the wagon with the flat rack and tipping trailer was 0.590 m above the maximum permissible load height.

Following the accident, QR measured the clearance between rail and the structure of Alexandra Bridge to be 4.312 m, which was 12 mm more than the bridge’s design clearance. Figure 7 compares the outline of a standard shipping container with the height of the Alexandra Bridge and the height of the tipping trailer’s hydraulic lifting post.

Figure 7: North Coast Line standard container loading outline[4] with overlays of tipping trailer and Alexandra Bridge beam heights

All measurements are in mm. The added Alexandra Bridge and tipping trailer height overlays are for illustrative purposes only.

Source: Aurizon, modified by ATSB

The track south of Rockhampton was electrified with sections of overhead contact wires as low as 4.349 m above the track level.

Stuart terminal

The Stuart terminal was an intermodal freight facility about 11 km south of Townsville that was cooperatively operated between Linfox and Aurizon. Linfox was responsible for the movement of road freight to and from the terminal and owned the wagons, with a ‘hook and pull’ (wagon hauling) agreement in place with Aurizon. Aurizon conducted the loading of rail wagons and was responsible for rail operations and rail safety, including the safety and integrity of loads. This arrangement meant that there was a combination of both Linfox and Aurizon personnel working at the terminal.

Most of the freight passing through Stuart Yard was in 20-foot or 40-foot containers, though occasionally non-containerised freight was also transported.

At the time of the occurrence, Aurizon was responsible for loading trains at Stuart and one other terminal on the North Coast Line. At other terminals (such as Acacia Ridge), Linfox was responsible for the loading.

Freight booking information

Aurizon and Linfox used a freight management system called A2B to coordinate the movement of items.

Provisions were in place where freight known to be exceeding the standard outline could be transported. In those circumstances, when freight was known to be out of gauge, an authority to travel (ATT) authorisation was required to be obtained with specific restrictions (for example, only to travel through certain tracks or not to pass other rail traffic in certain areas). Even with an ATT in place, there was still maximum limitations due to various factors, such as tunnel sizes, overhead electrical equipment and bridges. Where an ATT was approved, the freight terminal would be advised directly, and a notation made on the consignment note applicable for the freight being transported, warning the loading operators of the oversized item.

Linfox reported that clients normally booked freight through its customer service team. Any non-standard freight bookings (or freight that did not fit into standard containers) would be referred to a manager for approval. In this case, however, the tipping trailer was an internal asset that was already in the yard at Stuart and the booking process bypassed this process.

The Linfox warehouse supervisor at the Stuart terminal had only recently (within 3 months) commenced work at that terminal. They reported that they had arranged for the transport of tipping trailers by rail when working at another depot in another state, but had not previously arranged for transport of a tipping trailer from the Stuart terminal or on the North Coast Line.

Linfox advised that it had processes for checking the dimensions of freight at terminals where Linfox were involved in loading freight onto trains. However, since Linfox did not load freight onto rolling stock at the Stuart Terminal, there was no procedure in place for measurement of the dimensions of any non-standard freight received at the Stuart terminal prior to requesting Aurizon personnel to load the freight onto a train. The warehouse supervisor also advised that they were not aware of the specific dimensions of loads that were allowable on the North Coast Line. They were relying on the Aurizon personnel at the terminal to check the load and determine whether the load was suitable for rail travel. This was consistent with the process they were familiar with when working at other terminals.

Freight loading information

Aurizon’s Loading and Securing Standard provided instruction on the safe transport of different types of freight by rail or road throughout Australia. It noted that a rail infrastructure manager (RIM) was responsible for defining freight outlines and for the authorisation of out-of-gauge loads, and a rolling stock operator was responsible for ensuring freight complied with the RIM’s instructions. It also stated that, for rail transport, the rolling stock operator (in this case Aurizon) was responsible for ensuring:

- Loading that exceeds or infringes the permissible outlines applicable to the type of loading and the routes over which it will travel is not transported, unless it has a valid out of gauge certificate

- All loading that is suspected of being close to or outside the applicable outline is referred to the RIM for investigation

Aurizon’s Loading and Securing of Freight Manual emphasised that out-of-gauge loads were not allowed to travel on Aurizon trains without an ATT. It also stated that the workers responsible for loading and securing freight were responsible for (among other things) ensuring that freight was loaded so that its overall size was within the (specified) standard loading outlines. Aurizon provided such personnel with a checklist for loading and securing flat racks, which included the loading outline and maximum allowed dimensions.

The Aurizon heavy lift (forklift) operator had worked in that role at the Stuart terminal for about 10 years, and they had undertaken the organisation’s online loading and securing training within the required time period. The heavy lift operator could not recall loading any out-of-gauge loads in the last 5 years. They stated they had knowledge of other (heavy road vehicle) trailers being transported on flat racks without any problems, and they also thought (but were not sure) that tipping trailers had been transported before. At the time they loaded this specific tipping trailer, they did not consider the height to be an issue. They had received no indication through the consignment note, their supervisor or the Linfox warehouse supervisor that the load was actually or potentially out of gauge. Other personnel who saw the loaded flat rack also indicated that they did not consider the height to be an issue.

Personnel reported that shipping containers were sometimes used as a general indication of the allowable freight envelope. On this occasion, although a 20-foot shipping container[5] was near the tipping trailer when it was loaded onto the flat rack by Linfox personnel, there was no container on the ground near the flat rack when it was lifted onto the wagon. The heavy lift operator also stated that there were no other containers on adjacent wagons at that time. There were containers loaded on the adjacent wagons when the completed rail consist was inspected at the Stuart terminal and at Merinda.

Aurizon advised the ATSB that pre-loaded flat racks that arrived at the terminal needed to pass an incoming inspection at the terminal’s entrance gate. However, it rarely received loaded flat racks via the entrance gate. Aurizon also advised that it was not a routine or consistent practice for the documented dimensions of non-standard freight to be physically verified, or for the train’s loading outline to be measured, during the loading process.

In addition, there were no tools or equipment provided for checking the dimensions of non-standard freight. Aurizon previously had a load height-measuring staff at Stuart to gauge a train’s height. This L-shaped staff or pole was held next to a wagon, and if the total load exceeded its height, that wagon would not be allowed to travel. This staff was a locally-implemented risk control; Aurizon’s safety management system did not specifically require it to be in place. After moving from previous facilities to the current Stuart terminal, the staff was no longer available to loading personnel.

The Stuart terminal did not have a viewing platform to assist with identifying out-of-gauge loads. There were also no other devices installed at the terminal to verify that loads were below the maximum permissible height or indicate over-height loads.

The ATSB has previously investigated a number of other occurrences involving loads out of gauge or not effectively secured. Some recent investigations include:

- On 15 June 2020, a wagon body became dislodged from the bogie during unloading at Coopers Plains, Queensland.[6] As part of the consist of train 2BW4, the wagon body later contacted and caused damage to platforms at Grafton, Coffs Harbour, Taree, Wingham and Dungong, New South Wales. The train had been inspected before departure, and again after damage to the Grafton platform was identified.

- On 18 August 2018, a collapsible rear end wall of a flat rack raised up en route and contacted an overpass on approach to Cooroy, Queensland, pulling down 1.3 km of high voltage overhead line equipment.[7] The ATSB found that personnel at the Acacia Ridge terminal did not check the collapsible end walls of the flat racks were secured on arrival at the terminal and after the flat racks were loaded. In addition, Aurizon, did not have an effective system in place for ensuring personnel required to check the securing of unusual loads (such as empty flat racks) prior to departure had sufficient knowledge of their responsibilities, and had ready access to relevant procedures, guidance and checklists.

- On 16 January 2018, an incorrectly-secured container on freight train 2BM9 collided with station infrastructure at Maitland, New South Wales, causing damage to gutter retaining brackets.[8] The investigation found that the departing train inspection did not detect the incorrectly-secured container, and that the collision with infrastructure was also partially due to raised track height at the station relative to the documented design.

Safety analysis

Out-of-gauge load

The total height of the wagon, flat rack container and tipping trailer’s hydraulic lifting post was 4.410 m, which exceeded the maximum allowable height for the North Coast Line by 0.590 m. The clearance for Alexandra Bridge was 4.312 m from the top of the rail, which meant the load was about 0.1 m too high for the bridge.

The driver was unaware of the collision due to the train’s low speed and the location of the wagon near the rear of the consist. Instead, the damage was identified by personnel at the Rockhampton yard, which ensured the out-of-gauge load did not continue further on the network. Had the trailer not been damaged by the collision with the bridge, it would have also exceeded the clearance height of the electrical overhead lines in various locations between Rockhampton and Brisbane, posing a significant hazard.

Processes for detecting out-of-gauge loads during freight booking

A large proportion of freight passing through the Stuart terminal was in shipping containers and therefore fitted within the required dimensions to be transported by rail. Freight that did not fit in a container still had to remain inside the maximum permissible outline for transportation to avoid collision with trackside objects and other rail traffic.

The potential for a non-standard load to be out of gauge should be evaluated during the booking process. In this case, as the tipping trailer was a Linfox asset being moved from one freight terminal to another, it was not managed through the organisation’s normal process for client bookings, which required any non-standard loads to be referred to relevant management personnel for approval when the load was being entered into the freight management system.

Instead, an informal process was used on this occasion, which involved the Linfox warehouse supervisor at Stuart requesting a capacity officer to make a booking. Because of the incomplete way the trailer was described to the Linfox capacity officer (that is, as a trailer, which would normally fit well within the required dimensions), there was limited opportunity for that officer to identify that the load was potentially out of gauge.

Accordingly, the consignment information for the trailer did not identify it as at out-of-gauge load, which would have triggered a process to determine whether it could be given an authority to travel (ATT) authorisation. The consignment information also did not contain any indication that the load could potentially be out-of-gauge. It specified the trailer as a generic flat rack container with default and therefore incorrect dimensions and an incomplete description of the item (that is, it was not specified as a tipping trailer). This limited the opportunity for personnel at the terminal to determine its suitability for the rail corridor.

The trailer was loaded onto the flat rack by Linfox personnel at the Stuart terminal and observed by multiple Linfox personnel at the time. However, these personnel were responsible for providing the load from the road interface, and not with rail shipment. Consequently, they had no specific knowledge of the dimensional requirements of non-standard freight and routinely did not measure such freight to ensure it was within the required dimensions before handing it over to Aurizon personnel for loading onto a wagon.

Ideally all out-of-gauge loads will be identified prior to the freight being transferred to the organisation responsible for loading it onto the wagon or train. In this case, the problem associated with Linfox transporting an internal asset appeared to be a relatively rare event, and there were processes for checking the dimensions of freight at other terminals. Nevertheless, there can be a variety of reasons why potentially out-of-gauge loads may occasionally be received for transport, or loads may become out-of-gauge during the preparation and loading process. Accordingly, the organisation preparing freight for loading onto a train should ensure it has robust processes to identify such loads.

Processes for detecting out-of-gauge loads during freight loading

The Aurizon heavy lift operator had not recently encountered any out-of-gauge loads and was aware of many other trailers having travelled along on the North Coast Line. It is likely that most (if not all) of the other trailers were not the tipping type, and therefore fitted within the required dimensions.

Expectations based on past experience strongly influence where a person will search for information and what they will search for (Wickens and McCarley 2008), and they also influence the perception of information (Wickens and others 2013). In simple terms, people are more likely to see what they expect to see, and less likely to see what they do not expect to see. Accordingly, the heavy lift operator’s low frequency of encountering out-of-gauge loads and expectancies regarding the size and nature of previous trailers probably influenced their ability to identify the height problem associated with the hydraulic lifting post on this occasion. The absence of any information in the consignment note to indicate that the load was potentially problematic would have reinforced these expectations.

The perception of heights, lengths and distances can be subject to many biases, and are more accurate when there are known reference objects to use in close proximity. In this case, when the heavy lift operator lifted the load onto the flat rack with the tipping trailer onto the wagon, there were no useful reference objects (such as shipping containers) next to the trailer.

The heavy lift operator later conducted a walking inspection of the consist. When conducting this inspection from ground level, the view to the top of the hydraulic lifting post would have been affected by parallax error, which would have made identification of the over-height load more difficult. Although there were containers on adjacent wagons at that stage, the over-height lifting post was not identified. At that time, the heavy lift operator (and other personnel) probably had a high level of expectancy that all of the freight they loaded was within the required dimensions and they were focussed on checking that the loads were secure.

The out-of-gauge load was not detected during 2 subsequent roll-by inspections (one at Stuart and one at Merinda). This may have been associated with a similar expectancy that loads would be within the required dimensions.

Aurizon did not have a routine process in place at the terminal to measure the dimensions of non-standard loads, and there was also no equipment available to easily check the dimensions of loads. Aurizon previously used an L-shaped staff (or pole) to estimate the height of out-of-gauge or potentially out-of-gauge loads at the Stuart terminal, but this tool was no longer available at the time of the occurrence, so estimation of the height was left to the judgement of individuals. The tool had been developed locally at the freight operator’s previous facilities and it was not a requirement or formally recognised part of the rolling stock operator’s safety management system.

Inherent problems associated with relying on informal risk controls and then managing change have been noted in previous ATSB investigations.[9] A detailed review of the change management process in this case was considered beyond the useful scope of the present investigation.

Given the various factors that can influence the ability of personnel to correctly perceive the dimensions of loads, organisations involving in the loading and dispatch of freight trains therefore need to ensure they have suitable equipment, processes and practices for confirming or checking the dimensions of all non-containerised loads on wagons. Such risk controls would ideally include the equipment to automatically detect out-of-gauge loads. Alternatively, the use of equipment to make it easier and more reliable for relevant personnel to inspect loads and confirm that they are within permissible limits should be considered.

Findings

|

ATSB investigation report findings focus on safety factors (that is, events and conditions that increase risk). Safety factors include ‘contributing factors’ and ‘other factors that increased risk’ (that is, factors that did not meet the definition of a contributing factor for this occurrence but were still considered important to include in the report for the purpose of increasing awareness and enhancing safety). In addition ‘other findings’ may be included to provide important information about topics other than safety factors. Safety issues are highlighted in bold to emphasise their importance. A safety issue is a safety factor that (a) can reasonably be regarded as having the potential to adversely affect the safety of future operations, and (b) is a characteristic of an organisation or a system, rather than a characteristic of a specific individual, or characteristic of an operating environment at a specific point in time. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual. |

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the collision with infrastructure involving freight train 8796 at Rockhampton, Queensland, on 17 September 2021.

Contributing factors

- The dimensions of the tipping trailer were not entered correctly into the freight management system when the shipment was being arranged, and there was no indications that the trailer was potentially out of gauge.

- Linfox did not have a process for internal, non-standard freight movements at the Stuart terminal to be reviewed and approved for conformance to the permissible loading profile for transport via rail.

- Judging the load’s height without a reference, the heavy lift operator did not detect the over-height load when loading the wagon or later when conducting a walking inspection of the consist from ground level. This allowed the over-height wagon to enter the rail corridor.

- At the Stuart terminal, Aurizon did not routinely apply a process to verify that the dimensions of non-standard loads were within the permissible loading profile, and it did not have measuring equipment available to identify freight loads that were outside the permissible loading profile for transport via rail. (Safety issue)

Safety issues and actions

|

Central to the ATSB’s investigation of transport safety matters is the early identification of safety issues. The ATSB expects relevant organisations will address all safety issues an investigation identifies. Depending on the level of risk of a safety issue, the extent of corrective action taken by the relevant organisation(s), or the desirability of directing a broad safety message to the rail industry, the ATSB may issue a formal safety recommendation or safety advisory notice as part of the final report. All of the directly involved parties were provided with a draft report and invited to provide submissions. As part of that process, each organisation was asked to communicate what safety actions, if any, they had carried out or were planning to carry out in relation to each safety issue relevant to their organisation. Descriptions of each safety issue, and any associated safety recommendations, are detailed below. Click the link to read the full safety issue description, including the issue status and any safety action/s taken. Safety issues and actions are updated on this website when safety issue owners provide further information concerning the implementation of safety action. |

Absence of measuring equipment

Safety issue number: RO-2021-010-SI-01

Safety issue description: Aurizon did not have measuring equipment available at its Stuart Yard to identify freight loads that were outside the permissible loading profile for transport via rail.

Safety action not associated with an identified safety issue

| Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence. |

Additional safety action by Linfox

Linfox advised that it would train forklift and operations staff in Aurizon loading and securing and produce a quick reference guide for loaders.

Linfox also advised:

An awareness campaign has been completed so that all non-standard items are to be referred to and approved by the QLD Capacity and Rail Network Manager. This is regardless of its nature as customer freight or internal shipments.

Linfox are also considering the feasibility of making alterations to the WAVE software system (which has replaced the previous A2B system) to provide a systematic prompt for dimensions when non-standard containers types (flat racks or open top container) are lodged.

Glossary

ATT Authority to travel

CCTV Closed-circuit television

Out of gauge Exceeding the limits of the approved kinematic envelope, or outline, of the rail corridor to remain clear of obstructions

QR Queensland Rail

RIM Rail infrastructure manager

Sources and submissions

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- Aurizon

- Linfox

- Queensland Rail

- Rockhampton Regional Council

- the heavy lift operator, capacity officer and freight supervisor.

References

Wickens CD, Hollands JG, Banbury S and Parasuraman R (2013) Engineering psychology and human performance, 4th edition, Pearson Boston, MA.

Wickens CD & McCarley JS (2008) Applied attention theory, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

Submissions

Under section 26 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003, the ATSB may provide a draft report, on a confidential basis, to any person whom the ATSB considers appropriate. That section allows a person receiving a draft report to make submissions to the ATSB about the draft report.

A draft of this report was provided to the following directly involved parties:

- Aurizon

- Linfox

- the Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator (ONRSR)

- Queensland Rail

- the heavy lift operator, capacity officer and freight supervisor.

Submissions were received from Aurizon, Queensland Rail and ONRSR and additional information was received from Linfox. The submissions were reviewed and, where considered appropriate, the text of the report was amended accordingly.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2022

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

[1] Flat racks are a type of shipping platform designed for oversized loads that do not fit inside a standard shipping container.

[2] Out of gauge: exceeding the limits of the approved kinematic envelope, or outline, of the rail corridor to remain clear of obstructions.

[3] Roll-by inspection: an inspection conducted by a qualified worker to identify issues with the rail consist, normally for wheel lockups or dragging equipment. It was conducted while standing at ground level adjacent to the train as it slowly ‘rolls’ past the worker under locomotive power.

[4] The loading outline is a 2-dimensional cross-section of the maximum permissible envelope or shape of a rail vehicle at rest.

[5] The height of a standard 20-foot shipping container is about 2.6 m.

[6] ATSB investigation RO-2020-009, Wagon out of gauge on freight train 2BW4, Main North rail line, New South Wales, on 16 June 2020.

[7] ATSB investigation RO-2018-011, Dewirement involving freight train YC77, Cooroy, Queensland, on 18 August 2018.

[8] ATSB investigation RO-2018-003, Loading irregularity on train 2BM9, Maitland, NSW on 16 January 2018.

[9] For example, ATSB Occurrence Investigation AO-2009-072 (reopened), Fuel planning event, weather-related event and ditching involving Israel Aircraft Industries Westwind 1124A, VH-NGA, 6.4 km WSW of Norfolk Island Airport, 18 November 2009.