What happened

On 4 March 2018, the pilot of a Cessna 206 floatplane, registered VH-LHQ (LHQ), operated by Cloud 9 Seaplanes, was due to pick up two passengers from a park next to Sea World Resort at Southport Broadwater, Queensland, for a short charter flight to Stradbroke Island.

At about 0845 Eastern Standard Time,[1] the pilot arrived at the aircraft’s base and conducted a pre-flight inspection. At about 1000, he conducted a 6-minute positioning flight from LHQ’s base to Southport Broadwater, where he was due to collect the passengers. No problems or defects were identified during the pre-flight inspection or the positioning flight.

At about 1030, prior to the passengers boarding the floatplane, the pilot briefed them on the safe entry and exit procedures. The passengers boarded LHQ and, at about 1040, the pilot began taxiing. During the taxi, the pilot completed the passenger safety briefing. As part of the briefing, the passengers were shown the location of their life jackets and the location and operation of the emergency exits. To ensure the passengers understood how to operate the emergency exit, the pilot asked the passenger in the rear seat to practice opening the exit.

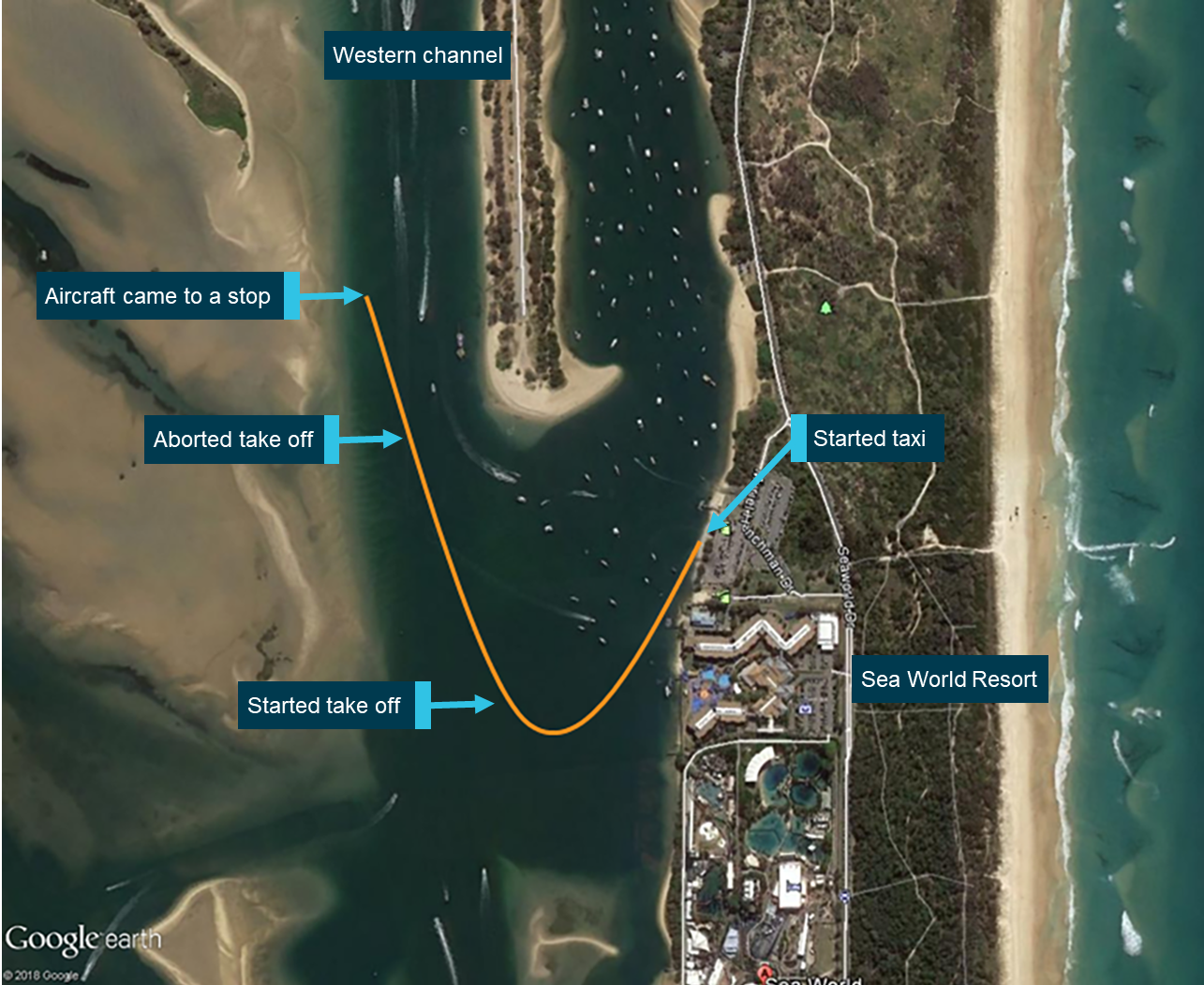

The floatplane had a relatively long taxi to avoid a large boat travelling south. After the boat passed, the pilot taxied to the eastern side of the western channel (Figure 1), passing over the boat’s wake.

Figure 1: Approximate aircraft taxi and take-off path

Source: Google maps, annotated by ATSB

Source: Google maps, annotated by ATSB

Shortly after, the pilot applied take-off power. The take-off run was normal and the pilot put the aircraft on the step.[2] The pilot reported that take-off run was a little bumpy, due to the wakes of some speedboats in the vicinity, but he did not consider it out of the ordinary. At about 30 kt, the aircraft started to ‘wobble’ from side-to-side. Moments later, the nose pitched down and the propeller contacted the water. In response, the pilot pulled back the power and mixture and attempted to steer the aircraft in a straight line – there was little steering control.

The aircraft came to a stop about 300 m from the shore. The pilot reminded the passengers of how to put on their life jackets, before he got out of the aircraft to assess the floats for damage. He found the front spreader bar of the floats had fractured but the floats were intact. As they were intact, he decided not to evacuate the passengers. No one had been injured.

The pilot then deployed and secured the floatplane’s anchor. About a minute after the occurrence, a parasailing boat whose occupants had witnessed the accident came alongside the aircraft. The passengers were transferred to the boat and taken ashore.

After another couple of minutes, a voluntary marine rescue boat arrived at the scene, and arranged to tow the substantially damaged aircraft onto a nearby beach (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The damaged Cessna 206 aircraft

Source: Operator

Floats

The aircraft was equipped with Aerocet seaplane floats. These floats incorporated composite float hulls, separated by two aluminium spreader bars and mounted to the aircraft with aluminium struts. Flying wires stabilised the mounting to the aircraft, and the spreader bars were attached to a socket inside the float.

The manufacturer provided an inspection regime for the floats, which included 25, 100 and 200‑hour inspections. The maintenance manual included repair procedures for minor damage and information on when the manufacturer should be consulted about damage and repairs. The floats did not have a service life limitation and operated ‘on condition’.

The maintenance manual, however, did indicate that ‘exceptional inspections’ were necessary to identify possible damage to the floats. The manual listed the following scenarios that could make such inspections necessary:

- Landing on grass or other runway

- Harsh landings

- Impact with submerged objects

- Suspected damage during tie-down or mooring, such as from wind or wave action

- Excessive water during pump-out or pre-flight inspection

The floats were installed new in June 2016, after the operator acquired LHQ. At the time of the accident, the floats had about 370 hours in service. The maintainer had conducted a visual inspection of the floats 22 hours prior to the accident – no defects to the spreader bar were identified. The operator stated that he always carried out a visual inspection of the floats during the aircraft’s daily wash. The aircraft was last washed the day prior to the accident. No defects were identified during the wash or pilot’s walk around on the morning of the accident.

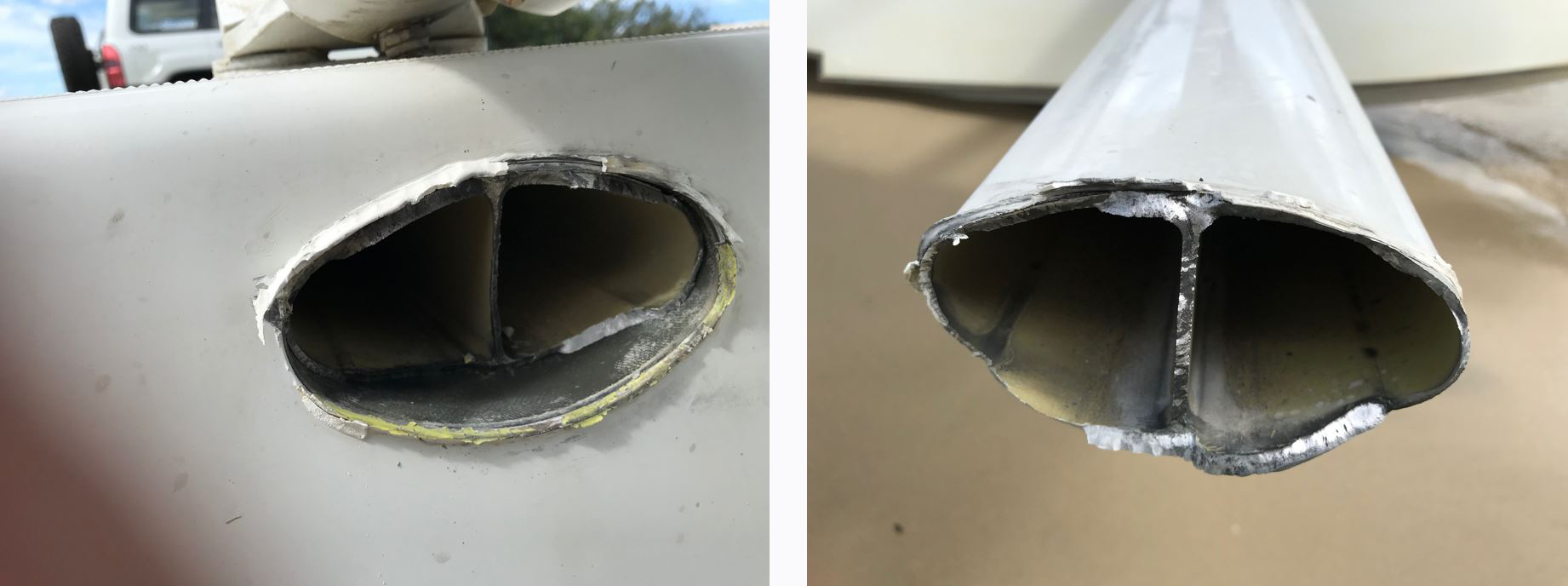

After the accident, the spreader bars were inspected and a fatigue crack was identified in the front spreader bar that had propagated to the point of failure. The failure was located about 3.5 cm inside the float so the fatigue crack was not visible (Figure 3). Cracks were also identified extending from the boltholes of the rear spreader bar. It could not be determined if these were a result of the accident or were pre-existing.

Figure 3: Front spreader bar fatigue failure located within the float

Source: Operator

The spreader bars were returned to the manufacturer for further analysis. As a result of that analysis, the manufacturer reported that there was ‘no apparent autogenous condition such as occlusions in the base material. It appears that repeated overloading of the float structure occurred leading to cracking in a difficult to detect location.’

Previous failure

In October 2015, the operator found a fatigue crack in a spreader bar in a similar location during his daily inspection on another set of Aerocet C206 floats. In that instance, the crack extended outside the floats and was detectable. The crack had extended to about 50 per cent of the spreader bar. The operator reported that failure to the manufacturer and provided the Civil Aviation Authority (CASA) with a defect report.

The manufacturer stated that no other operator had reported similar failures.

Operating environment

After the accident, the operator identified a number of factors that may have increased the stresses on the floats. These included:

- Conducting a high number of 5-minute scenic flights that increased the number of take-off and landing cycles per flying hour.

- When the seaplane is beached at Sea World resort, due to the angle of the beach, large boat wakes can hit the seaplane at a 45-degree angle. This results in the floats and spreader bars shuddering.

- During take-off and landing at Sea World and Couran Cove, cross wakes (two boat wakes colliding) can cause large waves and create a bumpy ride and excessive bounce and stress on the float hardware.

- Retrieval of the seaplane at the end of the day sometimes caused the seaplane to rock on the boat ramp when the plane was being loaded onto the trailer.

Safety analysis

During the take-off of LHQ, the floats’ front spreader bar fractured. This resulted in the floats separating forward of the floatplane’s centre of gravity and its propeller impacting the water.

The float system was designed and constructed with the spreader bar attached to a fitting within the float. This resulted in a section of the spreader bar that could not be visually inspected as it was also within the float. In this accident, the fatigue crack was located in that internal section of the spreader bar, which meant that it was not possible to visually identify it during normal operation and maintenance.

The operator had previously identified a fatigue crack in a spreader bar on another aircraft. In that instance, the crack had extended outside of the float and been identified prior to structural failure.

The operating environment increased stresses on the float assembly due to the short flights increasing the take-off and landing cycles per flight hour as well as increasing the amount of taxiing time per flight hour. This increased flight frequency, along with operating in a high water traffic environment, increased the loading on the floats.

Findings

These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

- During the take-off roll, the floatplane’s front spreader bar fractured resulting in the floats separating and the aircraft pitching down sufficiently for the propeller to contact the water.

- The origin of the fracture was a fatigue crack in the spreader bar section located inside the float, which meant routine visual inspections could not have detected the crack.

- Frequent, short flights in an area of high-water traffic exposed the floats and associated structure to high cyclic loading and stresses, increasing the likelihood of material fatigue.

Safety action

Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence.

Cloud 9 Seaplanes

The aircraft operator advised the ATSB that they had taken the following safety actions as a result of this occurrence:

Proactive safety action

- A borescope will be used to inspect spreader bars at intervals of 100 service hours.

- In addition to the 25 hourly inspection, the floats and hardware will be inspected while the floatplane is on the water. This will help to determine if there is any play in the fittings and hardware.

- Passenger loading has moved from Sea World Resort, to a location with a beach with less exposure to boat wake.

- Passengers and ropes will be used to keep the plane at a 90-degree angle to the water at all times when boat wakes are present. This will reduce uneven loading on the floats.

- A review of the take-off and landing areas and times will be carried out, to reduce rough and bouncy landings.

- The number of 5-minute scenic flights will be minimised to reduce the number of take‑off and landing cycles.

- The end of day procedure will be modified to reduce stresses on the floats when loading the seaplane onto the storage trailer.

Safety message

Scheduled maintenance inspections and the pilot’s daily inspection are a central element of the continuing airworthiness of the aircraft. However, continuing airworthiness also relies on inspections that allow the identification of damage, so that parts can be repaired or replaced prior to failure. In addition, where a structure may have experienced excessive loads (for example, hard landings) additional inspections may be required.

As was the case in this accident, it is important that defects are reported to regulators and aircraft manufacturers because they depend on accurate data to ensure the ongoing continued airworthiness of the aircraft. Defects reported to CASA through the Defect Report Service (DRS) system, and to the manufacturer, provide the opportunity for fleet trend monitoring and allow issues to be identified and rectified.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2018

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________

- Eastern Standard Time (EST): Universal Coordinated Time (UTC) + 10 hours.

- The step position is the attitude of the aircraft when the entire weight of the aircraft is supported by hydrodynamic and aerodynamic lift, as it is during high-speed taxi or just prior to take off. This position produces the least amount of water drag. The step is also called the planing position.