What happened

At 1136, on 12 August 2017, The Airplane Factory Sling 4 amateur-built aircraft, registered VH-BEG, departed Caloundra Aerodrome, Queensland, for a local private flight. There was a pilot and three passengers on board.

At 1143, the flight returned to Caloundra. Pilots of other aircraft reported that at the time wind conditions were light and aligned with runway 05.

The pilot positioned the aircraft to join the circuit for runway 12. The pilot of another aircraft advised runway 05 was in use and the pilot of VH-BEG then manoeuvred the aircraft to join the circuit for runway 05. While on the final leg of the circuit, the pilot selected full flap and observed parachutists descending to the right of the runway 05 threshold.

As the aircraft approached the runway, the pilot became concerned that the parachutists might drift into the path of the aircraft and focussed on the location of the parachutists. He then detected that the aircraft had deviated above and to the right of the desired approach path. The pilot then reduced power to idle and commenced a forward slip[1] to attempt to increase the approach angle and regain the desired approach path. As the aircraft approached the runway 05 threshold, he stopped the forward slip and began a left turn toward the threshold.

During the left turn, the aircraft aerodynamically stalled and the aircraft rolled to the left. Almost immediately, the left wing tip struck the ground and the aircraft collided with terrain. The fuselage fractured at the engine firewall, the engine was pushed rearward and intruded into the cabin.

The aircraft came to rest inverted and was destroyed (Figure 1). The pilot and all three passengers suffered serious injuries.

Figure 1: The Airplane Factory Sling 4 amateur-built aircraft, registered VH-BEG

The figure shows the wreckage of VH-BEG after emergency services had attended. Source: Queensland Police

Video footage

Video footage taken by the passenger in the left rear seat captured the final eight seconds of the flight.

The footage showed the aircraft in a forward slip with the nose yawed[2] to the right and tracking parallel to, but right of, the runway extended centreline (Figure 2). The indicated airspeed was 58 kt,[3] and the tachometer indicated idle power. The forward slip then stopped and the aircraft turned left toward the runway threshold. At the same time, the descent rate increased.

Figure 2: Images from video footage

The figure shows images of the aircraft during the approach prior to the accident. The aircraft is shown in a forward slip (left) and at the beginning of the turn toward the runway 05 threshold (right). Source: Passenger, annotated by ATSB

The aircraft approached the runway threshold on a heading of about 010 degrees magnetic, and appeared to be undershooting the threshold. Pitch angle then increased, an aerodynamic stall occurred, and the aircraft rolled rapidly left. As the aircraft rolled, the slip indicator displayed a full right deflection, indicating that the aircraft had entered an incipient left spin. The footage stopped as the left wing impacted the ground.

Pilot comments

The pilot of the aircraft provided the following comments:

- The pilot reported calculating the weight and balance of the aircraft prior to the flight using the aircraft electronic flight instrumentation system (EFIS) and using average weights for all occupants. He recalled the EFIS showing the aircraft weight and balance to be within the approved range.

- He did not consider conducting a go-around.

- The aircraft was fitted with a stall warning system, however, this did not activate prior to the accident.

Aircraft weight and balance

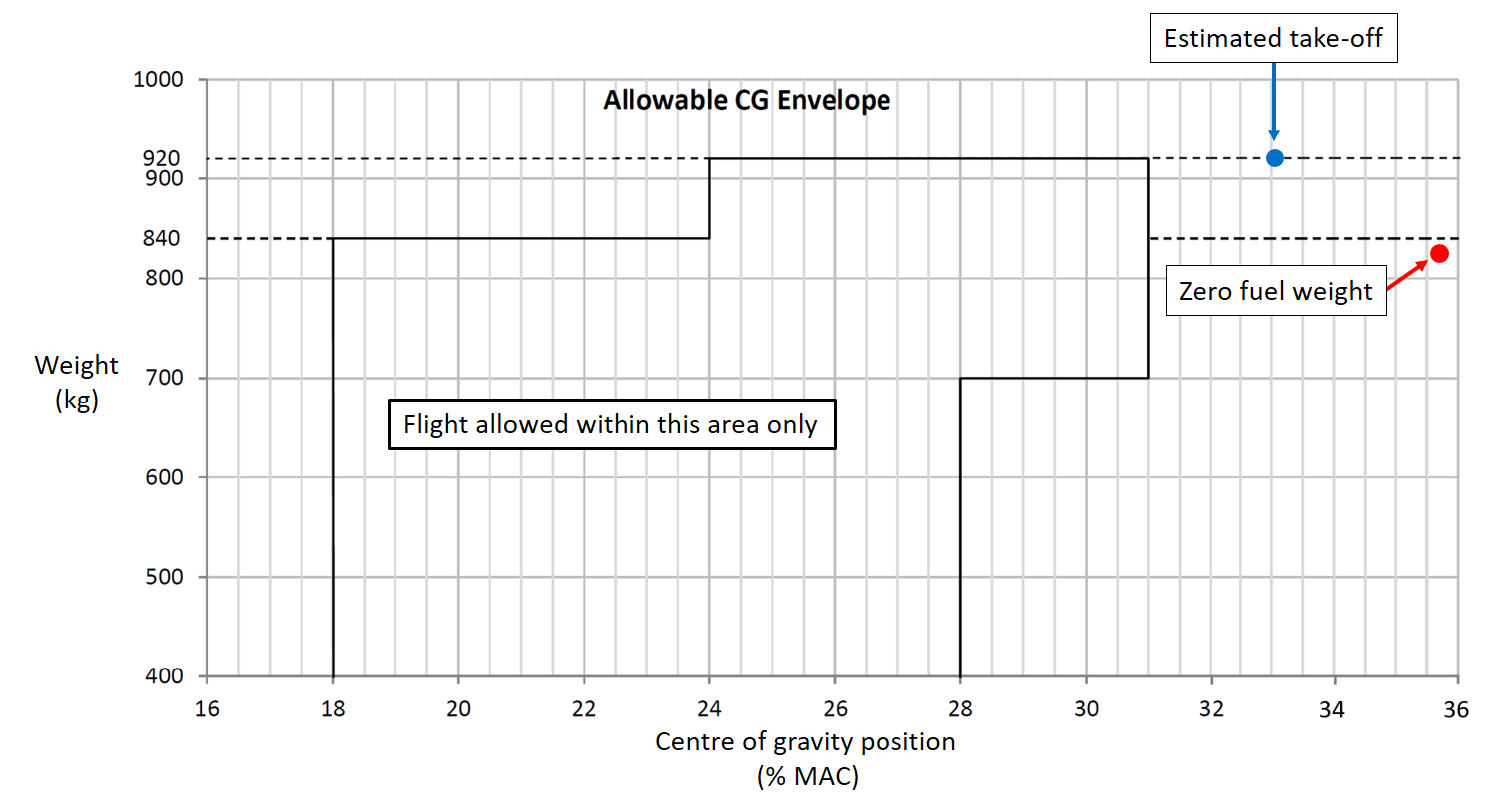

Weight and balance limitations were contained in the aircraft’s Pilot’s Operating Handbook (POH). The limitations defined the gross weight and centre of gravity limits. The maximum take-off weight of the aircraft was 920 kg and the aircraft was fitted with four seats.

The limits of the permissible centre of gravity range were defined as a percentage of mean aerodynamic cord (MAC):[4]

- The forward limit of the permissible range was 18 per cent MAC up to a gross weight of 840 kg, above this weight, the forward limit was 24 per cent MAC.

- The rear limit of the permissible range was 28 per cent MAC up to a gross weight of 700 kg, above this weight, the rear limit was 31 per cent MAC.

The empty weight of the aircraft was 461 kg. The weight of the front seat occupants was 190 kg and the weight of the rear seat occupants was 175 kg. The pilot estimated that at the time of take-off there was about 93 kg of fuel on board and reported that no items were carried in the baggage compartment.

Based on the above weights, the estimated take-off weight for the accident flight was 919 kg. The take-off centre of gravity position was 33.1 per cent MAC, and the zero fuel weight[5] centre of gravity position was 35.7 per cent MAC.

The centre of gravity position was outside of the permissible range for the entire flight (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Graphical representation of the aircraft centre of gravity for the accident flight

The graph shows the permissible centre of gravity range along with the calculated take-off and zero fuel weight centre of gravity positions. Source: Aircraft manufacturer, modified and annotated by ATSB

The pilot reported calculating the weight and balance to be within the permissible range using average weights.

The Civil Aviation Safety Authority advisory publication CAAP 235-1(1) Standard passenger and baggage weights provides the following guidance for using standard, or average, weights when calculating aircraft weight and balance:

Standard weights should not be used in aircraft with less than seven seats.

Because the probability of overloading a small aircraft is high if standard weights are used, the use of standard weights in aircraft with less than seven seats is inadvisable. Load calculations for these aircraft should be made using actual weights arrived at by weighing all occupants and baggage.

The New Zealand Civil Aviation Authority publication Weight and Balance contains the following information regarding the effects of operating an aircraft outside of the rear centre of gravity limit:

Your aircraft has centre of gravity limits, and any loading that puts the centre of gravity outside of those limits will seriously impair your ability to control the aircraft. The more aft the centre of gravity, the more unstable the aircraft. Forward pressure on the elevator control and full nose-down trim may be necessary to keep the aircraft from pitching up and stalling.

The further aft the centre of gravity is, the harder it is to recover from a stall.

ATSB comments

VH-BEG loading

Using the weight of the front seat occupants from the accident flight and allowing for no fuel and no baggage, the ATSB calculated that the maximum weight able to be carried in the rear seats of VH-BEG, while remaining within the allowable centre of gravity range, was just 118 kg. Using 105 kg of fuel as ballast, this weight increased to 148 kg. This allowed for 15 minutes of flight fuel and a 45-minute fuel reserve to be carried within the 920 kg maximum allowable take-off weight.

It was also found that when allowing for full fuel and any weight in the front two seats, the aircraft also required weight in the rear seats, or the baggage compartment, to ensure the centre of gravity was not located forward of the allowable range.

Warnings regarding weight and balance limitations included in the Sling 4 POH are shown in Figure 4:[6]

Figure 4: Warnings contained in POH

The figure shows warnings contained within the Sling 4 POH. Source: Aircraft manufacturer

Amateur-built aircraft regulations allow for some variance in construction which can lead to differences in the longitudinal balance and loading of individual aircraft. Pilots of amateur-built aircraft are reminded to be familiar with the weight and balance capabilities and limitations of their aircraft.

Pilot’s Operating Handbook incorrect data

During the investigation into this accident, the ATSB identified an error within the Sling 4 Pilot’s Operating Handbook, version 1.6.

The weight and balance calculation blank form on page 6-13 lists the location of the front seats as 1959mm aft of the datum. The correct figure is 1902mm, as detailed on page 6-4.

The pilot did not use the POH to calculate the weight and balance, therefore the error did not contribute to the accident. However, pilots of Sling 4 aircraft should ensure that weight and balance calculations are conducted using the correct figure.

Safety analysis

The flight was conducted with the centre of gravity aft of the rear limit. This had the effect of making the aircraft less stable and more susceptible to an aerodynamic stall. This also made recovery from a stall more difficult.

After detecting that the aircraft had deviated from the desired flight path, the pilot attempted to continue the approach by manoeuvring the aircraft at low level and low speed. The aircraft was loaded outside of the permissible centre of gravity range, and the manoeuvring further reduced the remaining margins of controllable flight until the aircraft stalled and control was lost.

During the manoeuvring, the aircraft stalled and entered an incipient spin. The stall and incipient spin occurred at a height from which recovery was not possible and the aircraft collided with terrain.

Findings

These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

- The aircraft centre of gravity position was aft of the rear limit.

- During the approach, the aircraft stalled and entered an incipient spin at a height from which recovery was not possible and the aircraft collided with terrain.

Safety action

Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following proactive safety action in response to this occurrence:

Aircraft manufacturer

As a result of this occurrence, the aircraft operator has advised the ATSB that they are taking the following safety action:

Change to documentation

- The position of the front seats in the blank form on page 6-13 of the Sling 4 Pilot’s Operating Handbook, version 1.6 will be corrected to show 1902mm aft of the datum.

Safety message

This incident highlights the critical importance of operating an aircraft within prescribed limitations at all times.

The United States Federal Aviation Administration publication Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge Chapter ten, Weight and Balance provides useful information for pilots to assist in correctly calculating aircraft weight and balance.

After detecting that the aircraft had deviated from the desired approach path, the pilot did not conduct a go-around. While the aircraft centre of gravity was located outside of the permissible range, a go-around, rather than manoeuvring at low speed and low level, may have prevented the accident from occurring.

The Flight Safety Foundation Approach-and-landing accident reduction tool kit Briefing note 6.1 – Being prepared to go around, stated that the importance of being go-around-prepared and go-around-minded must be emphasised because a go-around is not a frequent occurrence.

Purpose of safety investigationsThe objective of a safety investigation is to enhance transport safety. This is done through:

It is not a function of the ATSB to apportion blame or provide a means for determining liability. At the same time, an investigation report must include factual material of sufficient weight to support the analysis and findings. At all times the ATSB endeavours to balance the use of material that could imply adverse comment with the need to properly explain what happened, and why, in a fair and unbiased manner. The ATSB does not investigate for the purpose of taking administrative, regulatory or criminal action. TerminologyAn explanation of terminology used in ATSB investigation reports is available here. This includes terms such as occurrence, contributing factor, other factor that increased risk, and safety issue. Publishing informationReleased in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau © Commonwealth of Australia 2018

Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this report publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you wish to use their material, you will need to contact them directly. |

__________

- A forward slip is a manoeuvre where the pilot banks the aircraft and applies opposite rudder to maintain the original ground track. The manoeuvrer increases drag and allows an increase in descent rate without increasing speed.

- Yawing: the motion of an aircraft about its vertical or normal axis.

- During a slipping manoeuvre the indicated airspeed may not be accurate. The maximum take-off weight stall speed of the aircraft with full flap selected was 48 kt.

- Mean aerodynamic chord is a representative wing of constant section and distance from the leading to trailing edges (chord) which has the same aerodynamic behaviour as the actual wing.

- The weight of the aircraft including all contents and unusable fuel, but not including usable fuel.

- Centre of gravity (CG). Maximum all up weight (MAUW).