Safety summary

What happened

On the evening of 21 October 2016, a Eurocopter BK 117 C-2 helicopter, registered VH-SYB, departed Crookwell Medical helicopter landing site, New South Wales. The crew were returning to their home base at Orange, New South Wales, after conducting an emergency medical service (EMS) task. The flight was conducted as a night visual imaging system (NVIS) operation under night visual flight rules (NVFR), with the pilot and aircrew member (ACM) both wearing night vision goggles (NVG).

Shortly after take-off, the helicopter unexpectedly encountered low cloud, and the pilot initiated the operator’s inadvertent entry into instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) procedure. As the momentum of the helicopter’s climb reduced, the pilot lowered the helicopter’s nose to regain airspeed, but she inadvertently over corrected the pitch angle to 15° nose-down, as well as allowing a slight roll to the left. The resulting unusual attitude triggered a caution alert from the helicopter’s enhanced ground proximity warning system.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that the pilot had undertaken relevant recent training in inadvertent IMC recovery, and the pitch over correction was probably (at least in part) associated with the surprising nature of the event. In addition, during a high workload situation, the pilot was probably distracted by the reflection of the helicopter’s red anti-collision light reflecting off nearby cloud while wearing NVG.

In response to the distraction, the pilot asked the ACM to switch the light off. However, the ACM was not familiar (or required to be familiar) with the operation of the light switch, and inadvertently switched on the strobe light, which exposed the pilot to bright white light reflecting off cloud while wearing NVG. Exactly when the strobe light was switched on, and whether it contributed to the unusual attitude, could not be determined.

Earlier that evening, the pilot had diverted to Crookwell during a flight from Canberra to Orange due to the presence of thunderstorms and reduced visibility en route. The flight from Canberra to Orange was conducted under NVFR with NVIS, when the use of instrument flight rules (IFR) was practical and involved less risk. The ATSB identified that although the operator’s policies stated that EMS flights should be conducted under IFR where practical, this policy was not reinforced in the manual that covered NVIS operations. An IFR departure was not available for the take-off from Crookwell.

What’s been done as a result

As a result of this occurrence, the helicopter operator undertook several proactive safety actions, including clarifying its flight planning policy on IFR and NVIS operations and enhancing its training and advisory materials. The operator is also assessing the potential fitment of flight data monitoring equipment to all of its fleet.

Safety message

Although NVIS/NVG can significantly improve the quality and quantity of visual information available to pilots at night, the use of such devices also involves risk in some situations. This occurrence highlights the importance of ensuring that operators and pilots have robust processes for deciding when to conduct NVIS operations. It also serves as an example of the limitations and risks of NVIS operations when there are external light sources or reflections, and highlights the benefit of having a predetermined strategy for responding to degraded visibility conditions.

Overview

On the evening of 21 October 2016, a Eurocopter BK 117 C-2 helicopter, registered VH-SYB and operated by CHC Helicopter Australia, departed Crookwell Medical helicopter landing site, New South Wales (NSW). The crew were returning to their home base at Orange, NSW, after conducting an emergency medical service (EMS) task. The flight was conducted as a night visual imaging system (NVIS[1]) operation under night visual flight rules (NVFR), with the pilot and aircrew member both wearing night vision goggles (NVG).

Shortly after take-off the helicopter unexpectedly encountered low cloud. During the recovery from inadvertent instrument meteorological conditions[2] (IMC), the helicopter entered an unusual attitude, which triggered an enhanced ground proximity warning system (EGPWS) alert.

Previous flights to Young and Canberra

Earlier that day, at about 1627 Eastern Daylight-saving Time (EDT), the rostered crew accepted a task to transport a patient from Young, NSW to Canberra Hospital, Australian Capital Territory. The rostered day shift crew consisted of a pilot and aircrew member (ACM) and the medical team consisted of a doctor and a paramedic.

As the day shift pilot was completing the flight planning, the night shift pilot arrived at the operator’s base at Orange. Following a discussion, the night shift pilot agreed to take the task. The day shift pilot briefed the night shift pilot on the helicopter, personnel, forecast weather and flight plan.

The area forecast (ARFOR) for area 21 (which included Orange, Young and Canberra)[3] available at that time was valid from 1600 to 0400. For flights between Orange, Young and Canberra, the forecast included:

- scattered showers and isolated thunderstorms north of Young, with isolated showers in other areas after 2000

- rain developing after 2200

- broken[4] stratus cloud from 2,000-5,000 ft above mean sea level (AMSL) after 2000 and broken cloud in precipitation[5]

- visibilities of 2,000 m in thunderstorms, 3,000 m in rain, and 4,000 m in showers.

The flights from Orange to Young and Young to Canberra were expected to be completed well before to 2000. The aerodrome forecasts (TAFs) for Young and Canberra for the relevant period indicated the potential for showers but did not indicate any notable problems with visibility or low cloud.

The helicopter departed Orange at 1650 and landed at Young at 1728. While on the ground at Young, the pilot checked for updated weather information using the OzRunways[6] program on a tablet computer[7] provided by the operator. At that time the 1600 ARFOR was still valid, and the TAF for Canberra was effectively the same.

After the doctor and paramedic boarded the patient, the helicopter departed Young at 1818 and landed at Canberra Hospital at 1855. After the doctor, paramedic and patient disembarked at the hospital, the pilot and ACM departed Canberra Hospital to position to the operator’s base near Canberra Airport to refuel the helicopter. The helicopter landed at the base at 1918.

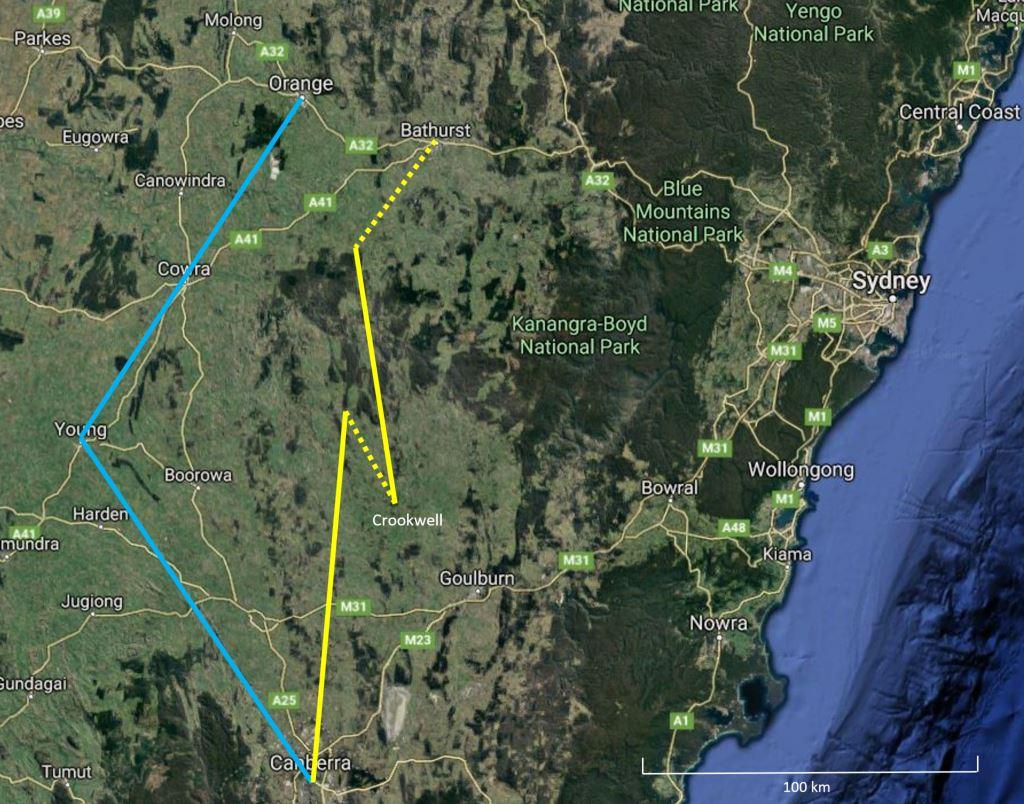

The flights between Orange, Young, Canberra Hospital and the operator’s Canberra base (Figure 1) were planned and conducted under day visual flight rules (VFR) in visual meteorological conditions.[8] No weather-related difficulties were reported to have occurred during those flights.

Figure 1: VH-SYB’s approximate flight path for outbound flights from Orange to Canberra (in blue) and return flights (in yellow), including diversion flight paths (yellow dots)

Source: Google maps annotated by ATSB

Preparation for the return flight from Canberra to Orange

During the late afternoon, the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) issued a significant meteorological information (SIGMET)[9] valid from 1850 to 2150. It provided information about thunderstorms in a squall line with hail north-west of Orange moving in an east, south-easterly direction at 35 kt.

An updated ARFOR for area 21, valid from 1900 to 1000, indicated some changes in the forecast weather conditions along the planned route from Canberra to Orange. Key details included:

- frequent thunderstorms in a squall line

- isolated thunderstorms with possible hail and scattered showers north of Young, with isolated showers in other areas

- rain developing

- broken stratus cloud from 2,000-5,000 ft AMSL after 2000 and broken cloud in precipitation

- visibilities of 2,000 m in thunderstorms, 3,000 m in rain, and 4,000 m in showers.

BoM subsequently issued an amended ARFOR valid from 1925 to 1000, which provided essentially the same information as the 1900 ARFOR.

An amended TAF for Orange was issued at 1729, but this forecast was basically the same as the previous (1200) forecast, indicating showers from 2000 and the potential for thunderstorms from 1900. The forecast also required the pilot to provide for a suitable alternate aerodrome when flight planning.[10]

While at the operator’s Canberra base, the pilot planned the return flight to Orange. She recalled that she checked for updated weather information using the OzRunways program on the tablet computer, and the ARFOR information she saw on the computer was unchanged from that which she saw prior to departing Young. The pilot reported that she was not aware of the updated 1900 ARFOR or the amended 1925 ARFOR, and did not recall any statement about frequent thunderstorms in a squall line. She noted that, had she seen that statement, she would not have departed Canberra.

The pilot planned the return flight to Orange under NVFR as an NVIS operation. She reported that conducting the flight under NVFR rather than instrument flight rules (IFR) as it provided more diversion options along the planned route.[11] The pilot uploaded the maximum fuel possible to cover inflight contingencies, and this included sufficient fuel to conduct an approach at Orange and, if required, divert to a suitable alternate aerodrome such as Bathurst.

At 1947, the helicopter departed from the operator’s Canberra base to Canberra Hospital to pick up the doctor and paramedic, landing at the hospital at 1953. While on the ground at the hospital, the paramedic viewed BoM weather radar information on his tablet computer and noted there was a line of thunderstorms extending from Moree (north of Orange) to Young. At about this time, the ACM received a text message from another ACM at Orange that stated there was a storm overhead Orange at that time.

The paramedic expressed concern about the situation and suggested they stay in Canberra, and the ACM agreed. The pilot recalled noting that the storms forecast for later that day appeared to have arrived earlier than expected, and that they would probably have passed through Orange by the time they arrived. She also believed the storms could be traversed safely.

The pilot advised the ACM and medical team that she had checked the weather forecast and, even after reviewing the BoM weather radar information, was happy to proceed with the flight to Orange. After a more detailed explanation of the flight planning from the pilot, including the en route alternatives and planning for contingencies, further discussion took place and the ACM and medical team agreed to conduct the flight.

Return flight from Canberra and diversion to Crookwell

The helicopter departed Canberra Hospital at 2010 for the return flight to Orange, with both the pilot and ACM wearing NVG. Shortly after departure, the pilot asked the paramedic if he still had any concerns. The paramedic recalled stating that he did, however, he would discuss it in the debrief at the end of the flight. The ACM subsequently reported to the ATSB that she also was not entirely comfortable conducting the flight due to the storms but did not voice those concerns again at this time.

While en route, the pilot and ACM continually assessed the movement of storms using the helicopter’s weather radar and ground-based weather radar using a tablet computer. The paramedic used his tablet computer to view the BoM weather radar information.

Approximately 20 NM north-west of Crookwell the pilot determined that the weather conditions were no longer suitable for continuing the flight due to closing gaps between the storms and reduced visibility ahead. After some discussion between the pilot, ACM and paramedic regarding suitable diversion sites, it was decided to divert to the Crookwell Medical helicopter landing site (HLS) (Figure 1).

At about 2100, the pilot conducted a visual approach (using NVG) to the Crookwell Medical HLS. After landing, the pilot, ACM and medical team went inside a rural fire service building to wait until the approaching storm cells passed.

Preparation for the flight from Crookwell to Orange

The pilot reported that, while on the ground at Crookwell, there was some rain but no storms passed directly overhead. The pilot monitored the weather situation using the OzRunways program and ground-based weather radar. The paramedic viewed the BoM weather radar information on his tablet computer.

The pilot later recalled that, again, the latest ARFOR displayed on the operator’s tablet computer was unchanged from that which she obtained prior to departing Young. She reported that she obtained the latest weather observations for Orange (including temperature and dew point) and Bathurst, and both indicated appropriate conditions.[12] No recorded weather observations were available at Crookwell.

After being on the ground for some time at Crookwell, the pilot noted that the storms appeared to have passed through. She went outside to check the weather conditions, and she conducted a visual scan and then a second scan with NVG to assess the conditions. She recalled seeing lightning flashes in the distance, which lit up the local area, showing no cloud, a small amount of rain and no haze.

During initial discussions about departing Crookwell, the paramedic stated that he was not comfortable that the storms had passed so did not think they should depart. After waiting a short period and having further discussions, the pilot, ACM and medical team agreed and planned for a departure under NVFR using NVIS at about 2240. The pilot, ACM and paramedic recalled that, when walking out to the helicopter, there was light rain but no lightning or other indication of thunderstorms or low cloud observed nearby.

Departure from Crookwell

Both the pilot and the ACM were wearing NVG for the departure from Crookwell. The pilot conducted a standard, hand-flown back-up take-off procedure to a decision point of approximately 120 ft. She then transitioned the helicopter to a forward climbing profile, increasing airspeed towards the take-off safety speed[13] (45 kt) with a positive rate of climb.

The ACM recalled that, during the initial part of the take-off, she had poor visibility due to a combination of effects from the helicopter’s searchlight and rain on the windscreen. She stated to the pilot that she had poor visibility, which the pilot noted.

The pilot recalled that the building floodlights and rain limited her vision ahead, but she had good visibility on the right-hand side, which she stated to the ACM. The pilot expected the visibility problems ahead would improve as the helicopter moved away from the building lights and the rain streamed off the windscreen with increased forward speed. Accordingly, she continued the departure.

The pilot reported that when the helicopter reached the take-off safety speed, she adjusted the helicopter attitude but the searchlight reflecting off the rain limited her forward visibility. She adjusted the searchlight down and to the right so she could see the ground more clearly, but the forward visibility did not improve enough for her to be comfortable with continuing the flight in that configuration. She then adjusted the helicopter’s attitude to slow the helicopter and help maintain visibility with the ground.

From this point, there was a rapid series of events. The pilot recalled that a flash of the anti-collision light reflecting off cloud alerted her to the presence of low cloud above. She immediately assessed that returning to land was no longer an option and called ‘inadvertent IMC’ while initiating the operator’s inadvertent IMC recovery procedure. She transitioned to flying on instruments, and commenced a rapid, vertical climb at maximum power, announcing that she was climbing to the other occupants. With the next flash of the anti-collision light, they had entered cloud.

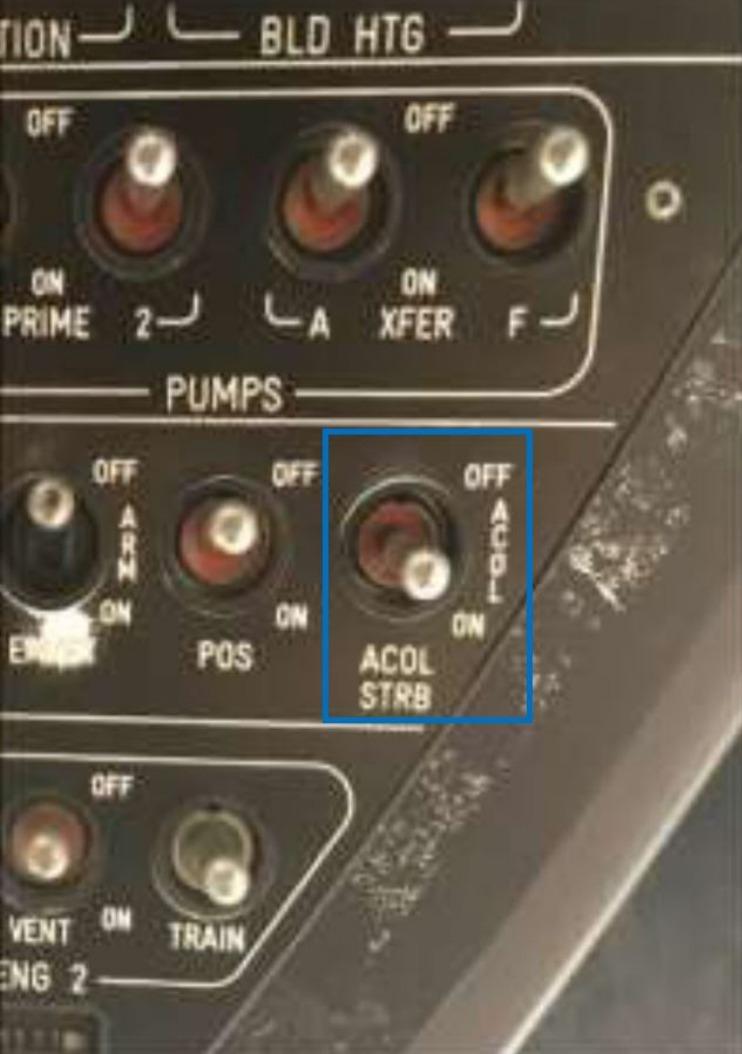

In an attempt to reduce the distracting effect of the anti-collision light, the pilot asked the ACM to turn the light off. The ACM removed her NVG, took a few seconds to locate the switch and, not realising the switch had three positions, inadvertently moved the anti-collision/strobe light switch from the ACOL (anti-collision light) position to the ON (anti-collision and strobe light) position. This changed the reflected light from red to bright white, which the pilot subsequently reported had a blinding effect on her vision while wearing NVG. The pilot again asked the ACM to turn the light off, which the ACM then actioned.

The pilot recalled that, during this period, the momentum of the helicopter’s climb was decreasing and the airspeed was reducing, so she lowered the helicopter’s nose to increase the airspeed. She recalled that she intended to lower the pitch angle by 5° but inadvertently overcorrected to about 15° nose-down, as well as inadvertently allowing a slight roll to the left. She also noted that during this period, the flashing of the reflected external lights had been distracting, and her transition to effective instrument scanning had not been ‘tidy’.

Very soon after the helicopter entered the unusual attitude, the enhanced ground proximity warning system (EGPWS) provided an aural ‘caution terrain’ alert. The pilot called ‘climbing, climbing, climbing’ and commenced unusual attitude recovery actions (in accordance with the operator’s procedure) by adjusting the helicopter’s attitude to wings-level and initiating a climb, with the helicopter still at full power. She recalled that the transition from the unusual attitude to the recovery attitude was conducted promptly and smoothly.

The ACM recalled that, following the EGPWS alert, she looked out the front windscreen and saw terrain. She also called out ‘climb, climb, climb’. During the climb, she noted that the airspeed had reduced close to 20 kt and stated the airspeed was low to the pilot. The pilot replied that she was happy to accept low airspeed at that stage in order to clear the terrain. Soon after, she adjusted the pitch attitude to increase airspeed.

Although the ACM’s recollection of many of the events during this period was similar to that of the pilot (above), there were some notable differences. More specifically:

- When the pilot slowed the helicopter down to maintain visual reference with the ground, the ACM recalled the helicopter also descended. However, the pilot did not recall any descent at that time.

- During the initial climb as part of the inadvertent IMC recovery, the ACM recalled that the pilot asked her to turn on the helicopter’s weather radar, which resulted in the ACM looking inside the helicopter. The pilot could not recall asking the ACM to turn on the weather radar until later (see Continuation to Orange and diversion to Bathurst).

- The ACM recalled that while she was looking inside the helicopter, she observed the vertical speed indicator (VSI) indicating a rate of descent of about 3,000 ft/minute, and it was at this time the EGPWS alert occurred. The pilot recalled seeing a figure of about 100 ft/minute at the time of the EGPWS alert (see also Helicopter performance).

- The ACM recalled that the pilot first asked her to turn off the anti-collision light during the climb after the unusual attitude event and EGPWS alert occurred. The pilot and the paramedic both recalled that the initial request to turn off the anti-collision light occurred during the earlier climb as part of the inadvertent IMC recovery (and before the unusual attitude event). The initial statements made by the pilot and paramedic soon after the occurrence also indicated that the inadvertent selection of the strobe light on occurred before the unusual attitude event. However, the pilot subsequently could not recall whether the strobe light was selected on before or after the unusual attitude event.

The pilot estimated that the unusual attitude event occurred between 200 and 400 ft above ground level (AGL). The ACM estimated that it occurred at about 500 ft AGL, and that she believed the helicopter could not have descended below 200 ft AGL as she did not recall the altitude alerter (normally set at 200 ft AGL during a departure) annunciating.

Continuation to Orange and diversion to Bathurst

Following the unusual attitude recovery, the pilot engaged the autopilot as soon as possible (after the helicopter reached the required minimum airspeed limitation) and continued climbing at best rate of climb towards the area’s lowest safe altitude for IFR flight (6,100 ft). She recalled asking the ACM to turn on the weather radar at this time, and she asked the ACM to change the destination on the helicopter’s GPS to Orange and obtain the latest weather information for Orange. The pilot contacted air traffic control (ATC) at 2246 and advised they had inadvertently entered IMC and requested to change flight rules from NVFR to IFR. ATC approved the request.

While tracking to Orange, the crew obtained weather reports that indicated the weather conditions at Orange were unsuitable for landing due to low cloud (with overcast cloud at 400 ft), whereas the weather at Bathurst was suitable. The pilot confirmed there was sufficient fuel to conduct an instrument approach at Orange and then divert to Bathurst, and elected to proceed to Orange.

When the helicopter was closer to Orange, the crew obtained further weather reports, which indicated the conditions at the airport had not improved (still overcast at 400 ft) but the conditions at Bathurst were still suitable.[14] Consequently, at 2311 the pilot requested clearance from ATC to divert to Bathurst, which was provided. The pilot diverted to Bathurst, conducted an instrument approach and landed at Bathurst Airport at 2331.

__________

- NVIS: a self-contained binocular night vision enhancement device that is (a) helmet mounted or otherwise worn by a person, and (b) can detect and amplify light in both the visual and near infra-red bands of the electromagnetic spectrum. The devices are usually googles, which are also known as night vision goggles (NVG).

- Instrument meteorological conditions (IMC): weather conditions that require pilots to fly primarily by reference to instruments, and therefore under IFR, rather than by outside visual reference. Typically, this means flying in cloud or limited visibility.

- Area forecast (ARFOR): routine forecasts for designated areas and amendments when prescribed criteria were satisfied. An ARFOR provided a forecast of weather conditions for the specified area from the surface to 10,000 ft above mean sea level (AMSL). The standard validity period was 12 hours but this could vary from state to state. They were normally issued about 1 hour prior to the start of their validity period.

- Cloud cover: in aviation, cloud cover is reported using words that denote the extent of the cover. ‘Sky clear’ (SKC) indicates no cloud, ‘few’ indicates that 1-2 oktas (or eighths) is covered, ‘scattered’ indicates 3-4 oktas is covered, ‘broken’ indicates 5-7 oktas is covered, and ‘overcast’ indicates that 8 oktas is covered.

- The terrain along most of the route between Canberra and Orange was 2,000-3,000 ft AMSL. For example, elevations included 1,886 ft at Canberra Airport, 3,112 ft at Orange Airport and 2,840 ft at Crookwell Medical HLS.

- OzRunways is an electronic flight bag application that provides weather, area briefings, and other flight planning information in Australia. It includes a weather manager that provides a visual representation of weather along a route, as well as significant meteorological information, weather radar and rain prediction.

- The operator’s tablet computer was used as an electronic flight bag (EFB). An EFB is a portable information system for flight deck crew members which allows storing, updating, delivering, displaying and/or computing digital data to support flight operations or duties. The tablet computer met the requirements for an EFB under Civil Aviation Order 82.0 (Air operator’s certificates – applications for certificates and general requirements).

- Visual meteorological conditions (VMC): an aviation flight category in which visual flight rules (VFR) flight is permitted – that is, conditions in which pilots have sufficient visibility to fly the aircraft while maintaining visual separation from terrain and other aircraft.

- Significant meteorological information (SIGMET): a weather advisory service that provides the location, extent, expected movement and change in intensity of potentially hazardous (significant) or extreme meteorological conditions that are dangerous to most aircraft, such as thunderstorms or severe turbulence.

- The amended TAF for Orange issued at 1729 indicated, for the period from 2000, visibility of at least 10,000 m, showers of rain, scattered cloud at 500 ft and broken cloud at 1,000 ft above ground level. It also indicated that, from 1900, there was a TEMPO with 30 per cent probability of deteriorations of up to 60 minutes due to thunderstorms with rain, as well as visibility of 2,000 m and broken cloud at 500 ft. The 1729 TAF was similar to the previous TAF issued at 1200.

- If the flight was conducted under IFR, the pilot would have only been able to conduct planned flights to aerodromes that had an instrument approach procedure. Relevant aerodromes near the intended route between Canberra and Orange included Cowra and Bathurst. Other off-route aerodromes included Goulburn and Young.

- The weather observation for Orange issued at 2130 was a special weather observation report (SPECI), which indicated visibility of at least 10,000 m and overcast cloud at 900 ft. However, SPECIs issued at 2200 and 2230 indicated visibility of at least 10,000 m and overcast cloud at 400 ft. For the period from 2045 to 2330 the SPECI temperature / dew point split was 1° C. The weather observations for Bathurst during this period were routine reports (METARs), which indicated visibility of at least 10,000 m and scattered cloud at 3,600 ft (2130), 2,400 ft (at 2200) and 2,000 ft (at 2230). The pilot obtained current weather reports via the aerodrome weather information service (AWIS), which may have been slightly different to the SPECIs / METARs, which are normally issued every 30 minutes.

- VTOSS or take off safety speed: the minimum speed at which climb shall be achieved with the critical engine inoperative, the remaining engine operating within approved operating limits.

- An amended TAF for Orange was issued at 2326, which included visibility of at least 10,000 m, showers in rain and broken cloud at 500 ft. The 30 per cent probability of periods of up to 60 minutes with visibility 2,000 m, thunderstorms with rain and broken cloud 500 ft was still included. ATC broadcast the amended TAF at 2327.

Personnel information

Pilot

The pilot held an Air Transport Pilot (Helicopter) Licence and Command Instrument Rating. This permitted her to conduct night visual flight rules (NVFR) and instrument flight rules (IFR) flights. She had a total aeronautical experience of about 5,065 hours including 602 hours on BK 117 helicopters. Her last command instrument proficiency check was conducted on 25 May 2016. Her last recurrent proficiency check (base and line check) was conducted on 27 May 2016.

The pilot was qualified for night vision imaging system (NVIS) flight and had last completed an NVIS proficiency check flight on 9 August 2016. This check included conducting recovery from inadvertent instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) exercises while wearing night vision goggles (NVG). No problems were noted on this proficiency check, or her other recent proficiency checks.

The pilot had conducted about 770 hours of night flying including about 300 hours on NVIS. She met the recency requirements to conduct both NVIS flights and IFR flights.

The pilot had a valid Class 1 Aviation Medical Certificate, and she stated that she had no health-related issues.

The pilot’s roster pattern included 2 days standby at work (0730-1730), 2 nights standby at work (1730-0730) and 4 days off. She was rostered on standby at work from 1730 to 0730 the previous night, but had not been required to conduct any flight tasks. On the day of the occurrence, the pilot’s rostered period commenced at 1730. She arrived at work early, for no particular reason, at about 1600. She stated that she did not feel tired prior to or during the occurrence flight.

The pilot reported that she had no specific pressure or reason to return to Orange that night. However, she felt a responsibility to complete the mission and to return the helicopter back to home base if possible and safe to do so, thereby allowing further emergency medical service (EMS) or search and rescue (SAR) tasking from the Orange base (see Operator information).

Aircrew member information

The aircrew member (ACM) had about 859 hours total experience, which included about 465 hours on the BK 117 C-2. She was qualified, met the recency requirements to conduct NVIS operations sitting in a control seat, and had last completed an NVIS capability check flight on 31 May 2016. She had been trained and assessed to provide assistance to pilots in deteriorating visibility conditions and in-flight recovery procedures.

In addition to their role as part of a rescue crew, an ACM’s role during EMS flights could include performing tasks at the request of and under the direct supervision of the pilot. These tasks could include operating the weather radar, radios, the GPS and the searchlight and, if required, calling normal and emergency checklists and monitoring responses.

The operator reported that initial training courses for an ACM provided a general overview of helicopter systems. However, ACMs were not specifically trained in the use of helicopter exterior light switches (such as the anti-collision/strobe light switch), and were not expected to operate such switches during flight. The ACM on the occurrence flight reported that she had not been asked to operate the anti-collision/strobe light switch during flight before.

The pilot reported that she was aware that some other ACMs she had flown with had operated the switch before. However, the pilot had not often flown with this ACM as they were normally on different rosters.

The ACM had the same type of roster pattern as the pilot. She was rostered on standby at work from 0730 to 1730 on the day of the occurrence. Although she had conducted some duty tasks during the day at the Orange base, she also had rest periods to manage potential fatigue. The ACM’s duty time associated with the patient transfer task commenced at the time of the tasking call. As a result, the delayed return flight did not exceed her maximum duty time limit of 14 hours.

The ACM recalled that, while on the ground at Crookwell, she felt tired, so she closed her eyes and rested for a period. The pilot recalled asking the ACM, prior to departing Crookwell, whether she was fit to continue the flight and the ACM agreed. However, in hindsight the ACM recalled that she was fatigued at that time as it had been a long day, and she should have stated she was fatigued and not able to complete the flight.

Aircraft information

General information

The BK 117 C-2 is a medium-sized, single main rotor and tail rotor helicopter with skid-type landing gear. It was fitted with two Turbomeca Arriel 1E2 turbine engines.

VH-SYB was manufactured in 2008. It was equipped for EMS operations and complied with the requirements of Civil Aviation Order (CAO) 82.6 (Night vision imaging system – helicopters). The model of NVG used during the occurrence flight were ITT M949 aviator night vision imaging system 9.

The helicopter was approved for single-pilot operations by day and night under VFR and IFR and was equipped with an autopilot, radio altimeter and weather radar. The helicopter could also be flown with two pilots, with both front seats fitted with appropriate flight controls and displays.

The helicopter was fitted with a Honeywell Mark XXI enhanced ground proximity warning system (EGPWS). The EGPWS was a terrain awareness and warning system (TAWS) designed for helicopters, with additional features. The EGPWS alert described by the occupants was a caution alert rather than a warning alert.

The helicopter did not have a flight data recorder fitted, nor was a recorder required under Civil Aviation Order 20.18 (Aircraft equipment – basic operational requirements).

Anti-collision/strobe light switch

The helicopter’s exterior lighting included navigation (position), anti-collision and strobe lights. The anti-collision light was a red, flashing light, mounted at the top of the vertical fin. It was normally required to be selected as ‘on’ any time the aircraft’s engines were operating. The strobe light was a white flashing light, located near the anti-collision light.

The anti-collision and strobe lights were operated by a toggle switch, located on the overhead panel above the pilot’s seat. The switch had three positions (Figure 2):

- OFF

- ACOL, which operated the helicopter’s red anti-collision light only

- ON, which operated the red anti-collision light and white strobe light.

Figure 2: VH-SYB’s anti-collision / strobe light switch

Source: CHC annotated by ATSB

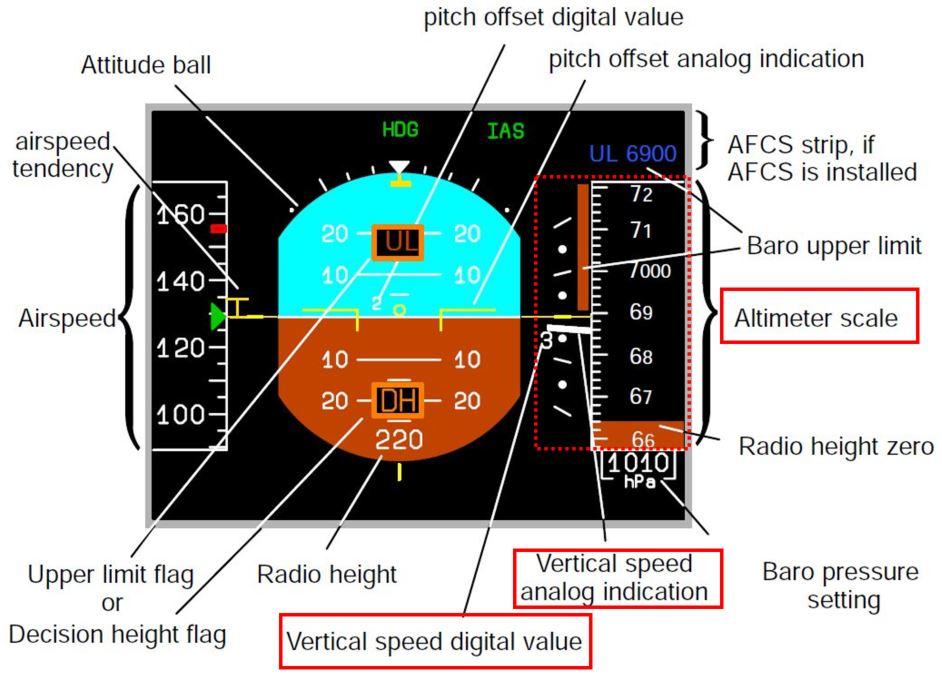

Flight control display system – Primary flight display

VH-SYB was fitted with a three-screen flight control display system, which included two independent primary flight displays (PFD). Each PFD (Figure 3) provided a pilot with primary flight data including attitude, altitude, airspeed and vertical speed.

The altimeter provided pilots with information as to their height above mean sea level. It was located on the right side of the PFD. In VH-SYB, the barometric corrected altitude was displayed with a numerical value every 100 ft and graduated markers every 20 ft.

The vertical speed indicator (VSI) provided pilots with information as to the helicopter’s rate of climb or descent. It was located immediately to the left of the altimeter and had a digital value and an analog indicator.

The analog indicator’s scale was from -2,000 ft/minute to +2,000 ft/minute with a graduated mark at every 500 ft. The digital indication was displayed as a value between -9,900 ft/minute and +9,900 ft/minute and it provided pilots a rate of climb or descent information even if the analog information was out of range. The displayed figure was in 100 ft/minute units (for example, ’3‘ equalled 300 ft/minute).

The BK 117 C-2 flight manual noted a limitation of the accuracy of the VSI, which stated:

Vertical speed indication may be unreliable in gusty conditions and at airspeeds around 30 kt during fast transition from hover flight into steep descent and from level flight to hover during rapid pull up’s.

Figure 3: VH-SYB’s primary flight display

Source: CHC.

Helicopter performance

As noted in Departure from Crookwell, the ACM recalled seeing the VSI indicate a rate of descent of 3,000 ft/minute at the time of the EGPWS alert. She also recalled seeing a rate of climb of 2,900 ft/minute during the initial unusual attitude recovery. The ACM stated she read these figures from the digital VSI display.

The helicopter had an all engines operating rate of climb of less than 2,200 ft/minute with gross weights above 3,000 kg (the approximate helicopter weight at the time of the occurrence). This maximum rate of climb would be lower if the helicopter had a low airspeed.

A rate of climb of 2,900 ft/minute would be beyond the performance capability of the helicopter, particularly given the low airspeed at the time. In addition, it is unlikely that a helicopter could transition from such a significant rate of descent to a significant rate of climb in a short period of time. Furthermore, the pilot, ACM and paramedic all stated that they did not experience any significant sensory feeling of acceleration forces acting on their bodies that would normally be associated with a helicopter rapidly recovering from a 3,000 ft/minute rate of descent to a 2,900 ft/minute rate of climb in a short period of time. The pilot also advised that the rate of climb and rate of descent figures recalled by the ACM were unrealistic.

The elevation of the Crookwell Medical helicopter landing site (HLS) was 2,840 ft. Therefore, indicated altitudes during the occurrence would have been slightly higher than 2,800 ft. Given the proximity of the altimeter to the VSI on the PFD, it is possible that the values recalled by the ACM during this high workload period may have been read from the altimeter rather than the VSI.

Meteorological information

Details of relevant forecasts and weather reports are provided in The occurrence. Based on the available information, the reported weather observations en route and at Orange were consistent with the issued forecasts.

The operator used tablet computers as an electronic flight bag (EFB) to assist pilots with various flight operations tasks, including obtaining weather information. The pilot had received training by the operator in the use of the EFB in accordance with the operator’s procedures. The crew had two operator-provided tablet computers on board the helicopter to provide redundancy.

Records from the National Aeronautical Information Processing System[15] indicated that weather information was accessed while the helicopter was on the ground in Young, Canberra and Crookwell. However, such records did not provide information about what forecasts or other weather information was accessed. The pilot reported that she used the EFB OzRunways program during the afternoon prior to the occurrence flight in the same way that she had always used it, and on no other occasions had she had a problem obtaining the latest weather information.

OzRunways advised that its program did not automatically download weather information from the Bureau of Meteorology. To obtain weather information, a pilot had to initiate a request. The OzRunways program presented users with the time of request and period of validity for the received area forecast. Received information was only stored for a maximum of 60 minutes, after which that information was no longer displayed. This feature mitigated the risk that a pilot would reference outdated weather information.

OzRunways advised the ATSB that it had not received any previous reports of a pilot not receiving updated weather information when using its program.

Helicopter landing site information

Crookwell Medical HLS (Figure 4), located to the northern side of the Crookwell Township, and was operated by the Crookwell Rural Fire Service (RFS). The HLS had no published IFR arrival or departure procedures. Its elevation was 2,840 ft and no weather information was available for the site. The concrete helipad was not equipped with standard pad lighting, although general floodlighting was available for night operations upon request to an RFS duty officer. Fuel and rest facilities were available, but there was no sleeping accommodation.

Figure 4: Crookwell Medical helicopter landing site

Source: OzRunways annotated by ATSB

Night vision imaging systems

Under visual meteorological conditions (VMC), NVIS/NVG amplify the amount of light reflected from the terrain. In most conditions and with proper implementation, NVIS/NVG provide pilots with a significant increase in the quantity and quality of visual information compared with unaided night vision. They allow a pilot to see the horizon, objects, terrain and weather more easily. Furthermore, they assist the pilot to maintain spatial orientation, to avoid hazards such as inadvertent entry into IMC, and to visually navigate.

Despite the advantages associated with NVIS/NVG, their application has limitations. Compared with optimal day vision, they are monochromatic, have a limited field of view, and a lower visual acuity. In addition, the quality of the NVG image is variable depending on the operating environment, and NVIS/NVG do not provide adequate imagery under all lighting, scene contrast, and atmospheric conditions. For example, the quality of an NVG image can vary depending on the amount of celestial illumination, the intensity of direct bright light, weather conditions, and the height above the surface and speed of the helicopter.

NVGs are not designed to be used for flight under IFR, however, it is possible to ‘see through’ areas of light moisture when using NVGs which increases the risk of inadvertently entering IMC.

CAO 82.6 (Night vision imaging system – helicopters) provided direction to NVIS operators of matters to be included in their operations manuals, including equipment standards, ongoing maintenance requirements, operating procedures and flight crew capability. Operators considering NVIS operations were required under CAO 82.6 to carry out a risk assessment prior to the commencement of operations or training with these devices.

The operator was approved by the Civil Aviation Safety Authority to conduct NVIS operations in accordance with CAO 82.6. The operator’s training and checking system ensured NVIS qualified pilots and ACMs maintained ongoing competency for NVIS flights.

Civil Aviation Advisory Publication (CAAP) 174-1(1) (Night vision googles – helicopters)[16] provided guidance to operators and pilots for the conduct of helicopter aerial work operations using NVIS. It discussed general information on NVIS and its capabilities, and limitations including environmental considerations as well as information on known human factors and physiological limitations.

Operator information

Flight planning policy

The operator provided its flight planning policies and procedures in multiple manuals. The Operations Manual Part A (OMA General/Basic Procedures) contained the operator’s VFR/IFR policy, which stated:

The Company policy is to conduct passenger carrying flights under the IFR. Other operations described in the OMF [EMS and SAR] and the OMG [external load and similar special operations] can be performed under the IFR or the VFR, but where practical IFR procedures are to be used.

However, a departure may be flown under the VFR to a predetermined changeover point, and IFR may be cancelled before landing when the commander has visual reference to the terrain (VFR then applies)…

The OMA defined a passenger as ‘any person other than an operating crew member carried on-board an aircraft.’

The Operations Manual Part F (OMF) contained the operator’s policies and procedures for EMS and search and rescue (SAR) operations. It stated a SAR/EMS crew normally consisted of a pilot (commander), ACM (or winch operator), rescue crewman (if a crew member was intended to be lowered by the winch) and other optional crew members required for the task (such as medical personnel).

The OMF further stated that EMS/SAR flights could be planned as IFR or VFR (as long as relevant limitations were met). In addition, it stated that NVIS operations under the VFR were permitted for specific types of flights, including EMS flights and positioning flights for EMS flights. There was no specific statement regarding the planning of return flights after a patient had been transported to a hospital.[17]

In terms of flight planning for NVIS operations under the NVFR, the OMF stated:

- no cloud was permitted up to 1,000 ft AGL within a 2 NM corridor either side of the planned track if the aircraft was IFR capable and the crew were IFR qualified (otherwise no cloud was permitted up to 2,000 ft)

- minimum visibility of 5,000 m.

The pilot interpreted the operator’s flight planning policies to mean the return flight from Canberra to Orange could be conducted under NVFR using NVIS, as the flight was still being conducted as part of an EMS mission; returning the helicopter and crew back to the base to enable their use for future tasking. The ACM reported that in her experience most, but not all, return flights were conducted under the IFR. The operator noted that its policy was for IFR to be used wherever practical for such flights. It also advised that, following the occurrence, it identified that this policy had not been applied consistently across all of its EMS/SAR bases.

The OMF stated that all NVIS flights were only permitted to be conducted in an IFR serviceable helicopter and crewed by an IFR rated and current crew (unless approved by the manager of flight operations). It also stated that one NVIS-qualified pilot was required for NVIS flights with an en route height at more than 1,000 ft AGL. For other flights, a second NVIS-qualified crew member was required (either a pilot or ACM) to assist the pilot.

Risk management of inadvertent entry into instrument metrological conditions

The OMF stated that pilots were to conduct a risk assessment for all NVIS operations as part of the pre-flight planning and briefing process. To reduce the risk of possible loss of control or controlled flight into terrain when encountering inadvertent IMC, pilots were required to include actions for inadvertent IMC in their departure and approach briefs.

The OMF included a list of specific NVIS hazards and relevant treatments (or risk controls) required by the operator and the crew to eliminate or reduce the risk to an acceptable level. The list of hazards included several related to inadvertent entry into IMC.

With regard to procedures for inadvertent entry to IMC, the operator’s OMA stated:

Loss of visual references can occur suddenly and with little warning in marginal weather conditions. Pilots should contingency plan regarding how to recover from inadvertent IMC... Consideration should be given to the elements of the missed approach briefing on an IFR approach as preparation.

An instinctive reflex to 'go back', descend rapidly or turn sharply to regain visual clues can be hazardous and may add to disorientation, possibly accompanied by loss of control and / or unintentional contact with terrain.

If the pilot has lost visual cues:

a. Follow the procedure… [for] Recovery from unusual attitude, ensuring that a heading is selected clear of known obstacles / terrain

b. Once safe flight is achieved, formulate a new plan

Inadvertent entry into IMC is a dangerous condition, and the immediate safety of the aircraft shall then take precedence over any rules relating to IFR flight plans, clearances, or normal rules for transition from VFR to IFR.

The OMF provided further details relating to loss of visual reference when using NVIS:

Despite careful preparation, the potential for inadvertent IMC penetration always exists. It is important that crews are able to recognise subtle changes to the NVIS image that occur prior to entry into instrument meteorological conditions. A loss of visual reference when conducting NVIS operations may be caused by a reduction in light levels that occur when moisture or haze is in the atmosphere. Visual reference may also be lost when terrain or obstacles obstruct the illumination from the moon or stars. Further, any build-up of moisture such as precipitation, mist, fog or cloud along with haze, smoke and dust may also lead to a loss of visual reference.

In areas where there is little lighting from built up areas, cloud cover will significantly reduce NVIS performance. Under cloud cover there is an increased likelihood of increased moisture that in the reduced light levels may go undetected until a total loss of visual reference has occurred…

When flying below LSALT the PF shall immediately apply climb power, obtain VTOSS or VY[18] as appropriate and climb to the minimum safe altitude. Depending on the situation prior to the loss of visual reference, manoeuvring over a safe area while climbing may assist in avoiding terrain, however that this will lead to a reduction in climb performance.

In the event of loss of visual reference the PF [pilot flying] shall announce "Losing visual reference – commencing IMC (intentions)".

Use of helicopter external lighting

CAAP 174-1(1) stated that exterior lighting such as an anti-collision lights and searchlights may have adverse effects on NVG. Light reflections off cloud or rain may interfere with NVG performance as the unit cannot adjust well to flickering or intermittent bright light. This causes rapid changes in the NVG image, which may be distracting and disorienting for the pilot.

Prior to NVIS operations, an operator was required to ensure that a helicopter’s exterior (and interior) lights were compatible with its NVG and met relevant standards. CAO 82.6 also stated that an NVIS operator was exempt from the requirements for using external aircraft lighting if complying with the CAO was at variance with the external lighting requirements.

The operator’s procedures stated that the use of NVIS to detect traffic was inconsistent, and that exterior lighting should be used as much as possible. The procedures also stated that:

If the helicopter's exterior lighting adversely affects NVIS performance, the commander must:

a. If he is satisfied there is no risk of collision with another aircraft: Turn off the exterior lighting, or

b. If he is satisfied there is such a risk: Immediately cease NVIS operations.

Goggle and de-goggle procedures

The OMF stated that time was required for each crew member to transition from aided flight (with NVG) to unaided flight (without NVG). It further stated that the crew was ‘not to goggle-up or de-goggle while in the hover’, and, where possible, the helicopter was to be at a safe height (generally above 1,000 ft AGL) before transitioning from (or to) NVGs. Crew members were required to transition one at a time (at the pilot’s direction), with each crew member clearly announcing when they had transitioned.

Crew resource management

The operator’s training and checking system included crew resource management (CRM) training. Pilots and ACMs were required to complete initial CRM training prior to commencing unsupervised line flying. Recurrent CRM training and assessment was then conducted annually. In addition to recurrent training, pilots and ACMs underwent in-depth CRM training during aircraft conversion and (for pilots) command upgrades.

The operator’s CRM program had a training matrix to ensure the structured delivery of major topics was achieved at least every 3 years. Human factors, threat and error management, decision making, leadership, team behaviour and communication and co-ordination inside and outside the cockpit were topics contained in the matrix. The pilot and ACM had both undertaken the operator’s CRM training program.

As previously noted, the operator had a risk management policy and procedure for all crew members involved in NVIS operations to follow prior to conducting such operations. The policy stated:

…all crew members involved in NVIS operations shall participate in the risk management of those operations. NVIS risk management involves recognition of those hazards that NVIS use may create and identifying and applying treatments to eliminate or reduce the risk to an acceptable level…

During operations, whether inflight or during the pre-flight process, crew members who believe that the planned or current NVIS operation is not in accordance with the operations manual or that risks exist that are not covered by the operations manual shall bring them to the attention of the pilot in command.

This policy was referred to by crew members as ‘All to say go, one to say no’ when referring to the decision to conduct a flight.

- The National Aeronautical Information Processing System (NAIPS) provides a central database of meteorological, NOTAM and chart information. The system is used by Airservices Australia to provide pre-flight and in-flight briefings and to accept and distribute flight notifications.

- CAAP 174-1(1), issued October 2007, was removed from the CASA website in July 2017. CASA subsequently issued CAAP 174-01 v2.1 in October 2017.

- A section in the OMF stated that a designated EMS call sign shall be applicable ‘for the full duration of the aircraft mission from call-out until return back to base and back on ‘standby’.’

- Vy is the best rate of climb speed.

Introduction

The flight from the Crookwell Medical helicopter landing site (HLS) to Orange was planned as a night vision imaging system (NVIS) operation under night visual flight rules (NVFR) with the pilot and aircrew member (ACM) both using night vision googles (NVG). During the take-off, the helicopter entered cloud, and soon after the helicopter entered an unusual attitude.

As far as could be determined, the unusual attitude occurred and was recovered more than 200 ft above ground level. Nevertheless, it triggered an enhanced ground proximity warning system (EGPWS) terrain alert, and an unusual attitude at a relatively low height and low airspeed has the potential to result in serious consequences.

This analysis first discusses flight-planning aspects, both in terms of the return flight from Canberra to Orange, which diverted to Crookwell, and then from Crookwell, as well as related crew resource management (CRM) aspects. It then discusses factors potentially associated with the unusual attitude, including the operation of the helicopter’s external lighting in cloud.

Flight planning aspects

Flight planning aspects prior to departing Canberra

When the pilot was on the ground in Canberra planning the flight from Canberra to Orange, there had been a significant meteorological information (SIGMET) issued, indicating thunderstorms in a squall line with hail. In addition, the current area forecast (ARFOR), valid from 1925, stated there were frequent thunderstorms in a squall line, as well as isolated thunderstorms with hail. The pilot reported that she checked the weather information using the operator’s tablet computer, but did not see the SIGMET or a statement in the ARFOR about frequent thunderstorms in a squall line. Instead, she recalled that the information in the ARFOR was the same as she had seen prior to departing Orange (which was issued at 1600 and included isolated thunderstorms).

Based on the available information, it appears likely that the latest ARFOR was available each time the pilot accessed weather information on the tablet computer. The time between the access at Young and Canberra was longer than the 60-minute time that the OzRunways program stored previously received information. The reason why the pilot did not notice the SIGMET or the updated ARFOR while on the ground at Canberra (or subsequently at Crookwell) could not be determined.

In addition to thunderstorms, the ARFORs issued at 1600, 1900 and 1925 all indicated broken cloud from 2,000-5,000 ft above mean sea level (AMSL), broken cloud in precipitation and scattered showers. The forecast for Orange also indicated there was showers, scattered cloud at 500 ft above ground level (AGL) and a TEMPO associated with reduced visibility, low cloud and thunderstorms with rain. Overall, these forecasts indicated there was a reasonable potential for encountering cloud and/or reduced visibility during the flight.

The pilot believed that, based on reviewing weather radar information, the forecast storms had passed through the area earlier than expected. She believed that conducting the flight under NVFR with NVIS offered more diversion options along the planned route, and she had ensured that there was sufficient fuel to arrive at Orange and then divert to a suitable aerodrome.

Pilots flying under visual flight rules (VFR) use visual information to avoid weather, obstacles and terrain, and to maintain control of an aircraft’s orientation. The amount of external visual information available to a pilot is significantly degraded during night operations. Although the use of NVIS normally increases the amount of visual cues available, this improvement is limited, particularly when there is a significant amount of cloud and/or precipitation. Overall, conducting the flight under instrument flight rules (IFR) was both possible and practical, and would have minimised the potential risk relative to doing the flight under NVFR.

The pilot reported that she felt no specific pressure to conduct the return flight to Orange, but believed there was an obligation to complete the mission by returning the helicopter to its home base to allow possible further emergency medical service (EMS)/search and rescue (SAR) tasking. However, conducting the flight under IFR would have provided a similar potential for reaching Orange, even though the flight may have had to divert further from the planned flight path.

The pilot also believed that under the operator’s flight planning policy, NVFR with NVIS was a permitted flight planning option for EMS positioning flights. Although the operator’s operations manual (Part A) clearly stated that IFR was to be used ‘where practical’ for all EMS/SAR flights, the procedures for EMS/SAR flights (in Part F) did not reinforce that policy or state a clear preference for when NVFR with NVIS versus IFR should be used. This created potential ambiguity regarding when VFR with NVIS could be used, and the available evidence indicates that other pilots also had not fully understood the operator’s intended policy.

If the flight from Canberra was conducted under the IFR, it is still likely that the pilot would have had to divert during the flight, due to thunderstorms along the planned flight path, with the most likely option being a return to Canberra. However, the decisions prior to departing Canberra were not considered to be contributing factors to the unusual attitude and EGPWS alert that occurred when departing Crookwell. Departures at night from locations such as Crookwell were well within the normal range of operations conducted by the operator.

Flight planning aspects prior to departing Crookwell

Crookwell Medical HLS was not equipped with a published instrument flight rules (IFR) departure procedure and there were no recorded weather observations available. Therefore, when planning the NVFR departure, the pilot had to rely on a visual assessment of the immediate weather conditions in conjunction with the ARFOR and recorded observations for Orange.

Although the thunderstorm hazard had passed, other hazards potentially remained so the pilot assessed the local weather conditions using a visual scan. She also conducted a second scan of the area using NVG. Although light rain was observed, the pilot’s scans of the local area did not detect any potentially associated low cloud.

The decision about whether to depart Crookwell was not straightforward, as departure under the IFR was not available and it was difficult to get detailed information about the weather conditions. In addition, if the crew and medical personnel remained at Crookwell, there were limited rest facilities available, and the helicopter would have been unavailable for further tasking.

Ultimately, the pilot obtained all the information that was available, and based on this information determined the local weather conditions were compliant with the requirements for a NVFR with NVIS departure. The ACM and paramedic’s recollections of the weather conditions at Crookwell were consistent with the pilot’s assessment, and they did not report having any concerns with the conditions prior to departure.

Crew resource management

The effective use of CRM and/or threat and error management will minimise risk in abnormal and emergency situations through identifying and discussing threats and hazards, ensuring all crew have the same understanding of the situation, involving all crew in key decisions and minimising workload.

To ensure CRM will be effective, pilots, ACMs and medical teams need appropriate training and guidance. The operator provided CRM training as well as a documented risk management policy and procedure for all crew members involved in NVIS operations that incorporated CRM aspects.

Prior to departing Canberra, the ACM and paramedic had significant reservations about the approaching line of thunderstorms, and they stated their concerns to the pilot. The pilot briefed the ACM and medical team about the weather conditions, advised she had uploaded sufficient fuel for en route diversions and holding, and that they had multiple diversion options on the route. The pilot had experience flying operations in thunderstorm conditions. It is likely that her confidence flying in similar weather conditions moderated the ACM’s and paramedic’s reservations, and led to them agreeing to conduct the flight even though they both still had concerns. However, with a more forceful relay of concern from either the ACM or medical team, it is likely the pilot would have decided to remain in Canberra.

Prior to departing from Crookwell, the paramedic initially stated to the pilot that he was not comfortable with departing as he was not confident the storms had passed, and the departure was delayed until all the parties were comfortable that the storms had passed. This was an effective use of the operator’s policy, which was described by crew members as ‘All to say go, one to say no’ when referring to the decision to conduct a flight.

The ACM subsequently reported that, in hindsight she was fatigued prior to the flight from Crookwell and should have stated to the pilot that she was fatigued. Based on the available information, it is difficult to make a conclusion about the extent to which the ACM was fatigued, and the extent to which her perception may have been affected by subsequent events.

Undesired attitude and recovery

Avoidance of instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) is more problematic at night because it is difficult to distinguish clear air from cloud in darkness. As a result, loss of already limited visual references can occur suddenly and with little warning in marginal weather conditions. Two main risks associated with flying in limited visibility are:

- spatial disorientation,[19] leading to loss of control of an aircraft and an uncontrolled flight into terrain

- inability to see and avoid obstacles while remaining under control, potentially leading to controlled flight into terrain.

As VH-SYB was not fitted with a flight data recorder it was not possible to determine the exact sequence of events or flight path of the helicopter during the departure from Crookwell. Based on the available evidence, the helicopter reached the decision point (120 ft) and the pilot transitioned the helicopter to a forward climbing profile, increasing airspeed towards the take-off safety speed (45 kt) with a positive rate of climb.

Shortly after this time, the weather conditions unexpectedly deteriorated and the pilot was unable to continue flight by visual reference using NVG. Soon after, the pilot identified that the helicopter was about to enter cloud, and she promptly commenced the operator’s inadvertent IMC recovery procedure, which involved a rapid, vertical climb at maximum power.

As the momentum of the helicopter’s climb deceased, the pilot intended to lower the pitch angle by 5° but she recalled that she inadvertently overcorrected to about 15° nose-down, as well as inadvertently allowing a slight roll to the left. This subsequently led to the helicopter entering an undesired attitude at low level, which resulted in the EGPWS alert. The pilot effectively identified the undesired attitude and successfully recovered the helicopter to normal flight by following the operator’s unusual attitude recovery procedures. The descent rate during the unusual attitude event could not be reliably determined.

In terms of the reasons for the unusual attitude, there was no known problems with the helicopter’s serviceability and there was no windshear or other environmental factors that directly affected the helicopter’s flight path. The unusual attitude appeared to result from the pilot’s overcorrection of the pitch attitude during her transition from visual flight (with her vision mainly focussed on external visual cues) to instrument flight (focussed mainly on the helicopter’s flight instruments), but the control difficulties did not appear to be related to pilot fatigue, medical or physiological problems. Other potential explanations involved instrument flying proficiency, expectancy and the distraction and other effects of the helicopter’s external lighting when the pilot was using NVG while flying in cloud (see next section).

The pilot met relevant recency requirements for IFR flight, and had conducted an IFR proficiency check 4 months prior to the occurrence and another proficiency check including inadvertent IMC recovery procedures 2 months prior to the occurrence. Research has shown that helicopter pilots with an instrument rating and recent experience are more successful in dealing with an unexpected entry into IMC than pilots who are not rated or do not have recent experience. Nevertheless, they may still encounter difficulties.

For example, one study found that commercial helicopter pilots who did not meet relevant instrument rating proficiency requirements were significantly more likely to lose control (67 per cent) than pilots who did meet the requirements (15 per cent) when unexpectedly entering IMC (Wuerz and O’Neal 1997). Another study showed that instrument-rated helicopter pilots’ performance (including control of pitch and bank) was significantly better in visual metrological conditions (VMC) than after they inadvertently entered IMC, and their performance in dealing with inadvertent entry to IMC in subsequent trials improved with recent practice (Crognale and Krebs 2011).

Other research has shown that airline pilots who are provided with unexpected emergency situations in a simulator do not manage these situations as well as when the emergencies are expected, with increased variability in pilot performance. This effect has been shown to occur with emergencies such as upset recoveries (Landman and others 2017) and stalls (Casner and others 2013), and it occurs with pilots who have successfully managed the same types of emergencies successfully many times before.

Overall, the pilot’s difficulty with controlling the helicopter’s pitch on this occasion was probably (at least in part) associated with the surprising or unexpected nature of the event. No problems were identified with the amount or recency of the proficiency checking undertaken by the pilot in the period prior to the occurrence.

Operation of helicopter’s external lighting

Workload refers to the interaction between an individual and the demands associated with the tasks they are performing. It varies as a function of the number and complexity of task demands and the capacity of the individual to meet those demands. High workload leads to a reduction in the number of information sources an individual will search, and the frequency or amount of time these sources are checked (Staal 2004). It can result in an individual’s performance on some tasks degrading, tasks being performed with simpler or less comprehensive strategies, or tasks being shed completely (Wickens and Hollands 2000).

When using NVG, helicopter external lighting can have various effects on a pilot’s vision and/or attention if the helicopter is near or in cloud. In this case, the helicopter’s red anti-collision light was selected as ‘on’ on prior to departing Crookwell, consistent with the operator’s normal procedures for night operations. The pilot reported that the reflection off cloud of the red flashing anti-collision light was distracting. Accordingly, she wanted the light switched off.

During the inadvertent IMC recovery, the pilot would have been experiencing a high workload and required both hands to control the helicopter. This prevented her capacity to de-goggle and manipulate the light switch. Therefore, it is understandable that the pilot instructed the ACM manipulate the light switching in this situation. However, the operator’s ACMs were not trained or expected by the operator to perform this cockpit function. Accordingly, when under higher workload, it is not surprising that the ACM inadvertently positioned the anti-collision light to the anti-collision and strobe light position. This resulted in a much brighter, white flashing light reflecting off the cloud, and the pilot reported that this had a significant, ‘blinding’ effect on her vision when using NVG.

In addition to impaired vision, exposure to an intense bright light could potentially lead to a range of other short-term performance effects when using NVG, including surprise and potentially a ‘startle’ response. It is therefore critically important to minimise the risk of pilots using NVGs to be exposed to such light, particularly during a critical stage of flight. The sudden onset of the bright light from the strobe light reflecting off cloud would certainly provide a viable explanation for the pilot’s difficulty managing the helicopter’s pitch attitude during the recovery from inadvertent IMC.

However, the extent to which the helicopter’s external lighting contributed to the pilot’s control of the helicopter was difficult to determine due to the inconsistency in the recall of the sequence of events by the pilot, ACM and paramedic. The recollection of the pilot and paramedic was that the pilot asked the ACM to switch off the anti-collision light prior to the unusual attitude event, whereas the ACM recalled that the unusual attitude event occurred first. A person’s memory about a sequence of events during a serious incident or accident can be affected by a range of factors, including the person’s workload, the complexity of the events, the pace at which the events occur and interference from other sequences of events that may occur before and after the sequence of interest. Even if many of the events are recalled, the memory of the sequence in which they occurred may not be accurate (Davis 2001).

Based on the available evidence, the ATSB concluded that the description provided by the pilot and paramedic was viable and more likely to be correct. Nevertheless, although the pilot probably asked the ACM to switch the anti-collision light off prior to the unusual attitude, this action would have taken some time to action and it is unclear whether the ACM inadvertently selected the strobe light on prior to the unusual attitude. Nevertheless, the flashing of the red anti-collision light off cloud, and the process of asking the ACM to select the light off and the ACM commencing this task, provided some level of distraction during a critical time, and probably influenced the pilot’s ability to effectively transition to instrument flight.

If a pre take-off risk assessment identified a realistic potential for entering cloud, then it would be reasonable to expect that the pilot would not undertake a flight using NVG. Alternatively, if some potential risk was identified, then the pilot had the authority to select the external helicopter lights off prior to departure (assuming there is no identified collision risk with other aircraft).

Once the pilot had encountered the unexpected situation, it would have been ideal if the pilot had been able to have the anti-collision light selected as ‘off’ reliably and quickly. However, the ATSB understands that it would not be a reasonable expectation for an operator to ensure that a non-pilot had received training and proficiency checking for such tasks so that they could successfully operate them in a high workload or emergency situation. In addition, there is also the associated risk of either of a front seat occupant de-goggling at a low altitude in such a situation.

It is difficult to estimate the extent of the distraction the anti-collision light provided on this occasion, however the effect would have been minimised if the pilot’s vision was focussed on the helicopter’s flight instruments. Recovery from inadvertent entry into IMC at low altitude is an emergency procedure, and therefore it would generally be appropriate for a pilot to focus on ensuring the helicopter was recovered to a safe height and flight path prior to dealing with distractions wherever possible.

__________

- Spatial disorientation occurs when a pilot does not correctly sense the position, motion and attitude of an aircraft relative to the surface of the Earth. Further information about spatial disorientation is provided in the ATSB report AO2011-102, VFR flight into dark night involving Aérospatiale AS355F2 VH-NTV, 5 km north of Marree, South Australia, 18 August 2011, available at www.atsb.gov.au.

From the evidence available, the following findings are made with respect to the terrain awareness warning system alert involving Eurocopter BK 117 C-2, registered VH-SYB, near Crookwell, New South Wales on 21 October 2016. These findings should not be read as apportioning blame or liability to any particular organisation or individual.

Contributing factors

- During the night visual flight rules take-off from Crookwell, the helicopter entered unexpected low cloud.

- The helicopter’s anti-collision light reflecting against nearby cloud distracted the pilot while she was using night vision goggles.

- When responding to the inadvertent entry into instrument meteorological conditions, the pilot over-controlled the helicopter nose down. The resulting unusual attitude at low altitude triggered the enhanced ground proximity warning system to provide a caution alert.

Other factors that increased risk

- Although the pilot had checked weather information for updates prior to departing Canberra, she did not identify significant changes in updated area forecasts pertaining to the planned route from Canberra to Orange. The reason the changes were not identified could not be determined.

- The flight from Canberra to Orange was planned to be conducted under night visual flight rules with the use of night vision goggles, when the use of instrument flight rules was practical and involved less risk, given the forecast and actual weather conditions.

- Although CHC Helicopter Australia’s operations manual stated that emergency medical service flights should be conducted under instrument flight rules (IFR) ‘where practical’, its procedures for night visual flight rules (NVFR) operations using night vision goggles did not clearly state when IFR rather than NVFR should be used. [Safety issue]

- The aircrew member and paramedic had significant concerns regarding the expected weather conditions for the flight from Canberra to Orange, but these concerns were not effectively communicated to, and/or resolved with, the pilot prior to them agreeing to depart Canberra.

- Due to the distraction of the red anti-collision light reflecting off cloud soon after take-off from Crookwell, and high workload, the pilot requested the aircrew member (ACM) to turn off the light. The operation of the light switch was not part of the ACM’s defined and trained duties, therefore creating potential for the task to not be conducted accurately or promptly.

- The aircrew member inadvertently positioned the anti-collision / strobe light switch to the anti-collision and strobe lights position, which resulted in the pilot being exposed to bright white light (reflecting off cloud) while using night vision goggles.

The safety issues identified during this investigation are listed in the Findings and Safety issues and actions sections of this report. The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) expects that all safety issues identified by the investigation should be addressed by the relevant organisation(s). In addressing those issues, the ATSB prefers to encourage relevant organisation(s) to proactively initiate safety action, rather than to issue formal safety recommendations or safety advisory notices.

All of the directly involved parties were provided with a draft report and invited to provide submissions. As part of that process, each organisation was asked to communicate what safety actions, if any, they had carried out or were planning to carry out in relation to each safety issue relevant to their organisation.

The initial public version of these safety issues and actions are repeated separately on the ATSB website to facilitate monitoring by interested parties. Where relevant the safety issues and actions will be updated on the ATSB website as information comes to hand.

Policies and procedures for planning IFR and NVIS flights

Safety issue: AO-2016-160-SI-01

Safety issue description: Although CHC Helicopter Australia’s operations manual stated that emergency medical service flights should be conducted under instrument flight rules (IFR) ‘where practical’, its procedures for night visual flight rules (NVFR) operations using night vision goggles did not clearly state when IFR rather than NVFR should be used.

Additional safety action

Whether or not the ATSB identifies safety issues in the course of an investigation, relevant organisations may proactively initiate safety action in order to reduce their safety risk. The ATSB has been advised of the following safety action in response to this occurrence.

CHC Helicopter Australia

As a result of this occurrence, the helicopter operator advised the ATSB it had undertaken the following safety actions:

- integrated its incident investigation and associated learnings into its crew resource management training package

- conducted a review of its simulator training program to ensure inadvertent instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) and unusual attitude procedures were adequately covered

- developed an accident prevention publication regarding inadvertent IMC scenarios

- conducted a review to assess the safety benefit associated with fitment of flight data monitoring equipment for those aircraft within the fleet that did not have it.

Sources of information

The sources of information during the investigation included:

- the pilot and crew

- CHC Helicopter Australia

- New South Wales Health Emergency and Aeromedical Services

- OzRunways Pty Ltd

- Bureau of Meteorology

- Airservices Australia.

References

Casner, SM Geven, RW & Williams, RT 2013, ‘The effectiveness of airline pilot training for abnormal events’, Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, vol. 55, pp.477-485.

Crognale, MA & Krebs, WK 2011, ‘Performance of helicopter pilots during inadvertent flight into instrument meteorological conditions’, The International Journal of Aviation Psychology, vol. 21, pp. 235-253.